The Impact of a Professional Development Program on English Language Teachers’ Classroom Performance

El impacto de un programa de desarrollo profesional en el desempeño en clase de profesores de lengua inglesa

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v16n1.38150Keywords:

In-service training, professional development, reflective teaching, English teacher competence, English teacher performance (en)desarrollo profesional, competencia del profesor de inglés, desempeño del profesor de inglés, enseñanza reflexiva, formación en servicio (es)

This article reports the findings of an action research study on a professional development program and its impact on the classroom performance of in-service English teachers who worked at a language institute of a Colombian state university. Questionnaires, semi-structured interviews, class observations, and a researcher’s journal were used as data collection instruments. Findings suggest that these in-service teachers improved their classroom performance as their teaching became more communicative, organized, attentive to students’ needs, and principled. In addition, theory, practice, reflection, and the role of the tutor combined effectively to help the in-service teachers improve classroom performance. It was concluded that these programs must be based on teachers’ philosophies and needs and effectively articulate theory, practice, experience, and reflection.

PROFILE

Issues in Teachers' Professional Development

Vol. 16, No. 1, April 2014 ISSN 1657-0790 (printed) ISSN 2256-5760 (online)

doi: https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v16n1.38150

The Impact of a Professional Development Program on English Language Teachers’ Classroom Performance

El impacto de un programa de desarrollo profesional en el desempeño en clase de profesores de lengua inglesa

Frank Giraldo*

Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira, Pereira, Colombia

This article was received on May 17, 2013, and accepted on October 15, 2013.

This article reports the findings of an action research study on a professional development program and its impact on the classroom performance of in-service English teachers who worked at a language institute of a Colombian state university. Questionnaires, semi-structured interviews, class observations, and a researcher’s journal were used as data collection instruments. Findings suggest that these in-service teachers improved their classroom performance as their teaching became more communicative, organized, attentive to students’ needs, and principled. In addition, theory, practice, reflection, and the role of the tutor combined effectively to help the in-service teachers improve classroom performance. It was concluded that these programs must be based on teachers’ philosophies and needs and effectively articulate theory, practice, experience, and reflection.

Key words: In-service training, professional development, reflective teaching, English teacher competence, English teacher performance.

En este artículo se presentan los resultados de una investigación-acción en un programa de desarrollo profesional y su impacto en el desempeño de clase de profesores de inglés de un instituto de lenguas de una universidad pública colombiana. Para recoger los datos se utilizaron cuestionarios, entrevistas, observaciones de clase y el diario del investigador. Los resultados sugieren mejorías en el desempeño de los docentes, ya que la enseñanza fue más comunicativa, organizada, atenta a las necesidades de los estudiantes y basada en principios. La teoría, la práctica, la reflexión y el papel desempeñado por el tutor se combinaron de manera efectiva para ayudar a los profesores a mejorar. Se concluye que los programas de desarrollo profesional deben planearse con base en las filosofías y necesidades de los profesores y articular la teoría, la práctica, la experiencia y la reflexión de manera más efectiva.

Palabras clave: desarrollo profesional, competencia del profesor de inglés, desempeño del profesor de inglés, enseñanza reflexiva, formación en servicio.

Introduction

The professional development of English language teachers has progressed from a transmission-oriented approach to one in which their realities are catered to. Scholars in the field of professional development and teacher education agree that these programs should respond to teachers’ needs, be based upon their close realities, and account for teachers as learners of their teaching. Furthermore, instead of top-down approaches in which experts “impose” models and recipes on teachers, authors urge context-sensitive models (González, 2007) that reflect teachers’ decision-making and experience.

Thus, the field of English language teaching has come to understand professional development not as the idea of an accumulation of skills but as a highly critical process. Freeman (1989) defines professional development as:

A strategy of influence and indirect intervention that works on complex, integrated aspects of teaching; these aspects are idiosyncratic and individual. The purpose of development is for the teacher to generate change through increasing or shifting awareness. (p. 40)

For the type of professional development Freeman defines to take place, there are different strategies, one of which is professional development programs. Authors such as Villegas-Reimers (2003), Díaz-Maggioli (2004), and Wilde (2010) agree that these programs must engage teachers in reflective and collaborative work; they must also include teachers’ skills, knowledge, and experience. Lastly, professional development programs should provide teachers with opportunities to develop their professional practice and receive feedback on it. Because of this type of practice, teachers are conceived of as learners.

Taken together, these authors recommend what professional development programs should be like. What we need to further understand is the actual realization of how these programs come about when they are designed and implemented. School support and adequate infrastructure as well as teacher willingness are some of the conditions for professional development programs to be successful.

By taking the aforementioned principles and conditions into consideration, this research study sought to elucidate the impact a professional development program would have on six English teachers’ classroom performance. The following sections describe how the specific professional development program influenced the teachers’ philosophies, understood as the framework composed of their skills, experience, knowledge, and beliefs in language teaching (Richards, 2011). Action research (Kemmis as cited in Hopkins, 1995) was used as a way to evaluate the program and how it contributed to teachers’ professional development.

This article begins with an overview of what professional development and classroom performance mean; it then explains to what problem the program responded, states the research questions, and describes the setting in which the study took place. Later, the article describes the research methodology for the study, including the data collection instruments and techniques. Finally, the findings are explained and conclusions argued on the specific matter of designing and implementing professional development programs for English language teachers.

Literature Review

In order to explore the issue of professional development, training should be defined as well. Freeman (1989) defines training as the learning of discrete teaching items. In a training program, the collaborator (or tutor) is in charge of teaching these discrete stratagems to teachers so that they improve teaching skills such as presenting vocabulary, responding to student answers, and others. Development, Freeman continues, is about helping teachers to develop constant awareness of their experiences as professionals. In professional development, the collaborator’s role is to help teachers to reflect upon their teaching.

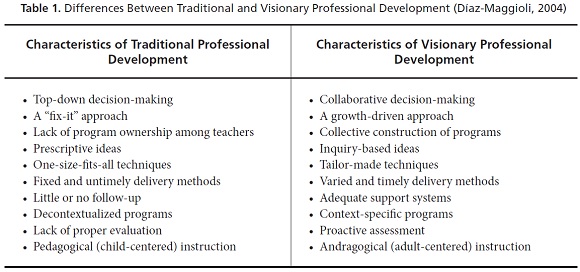

Díaz-Maggioli (2004) differentiates traditional development from visionary professional de- velopment. As can be seen in Table 1, the author understands the former as an approach to education in which teachers are recipients of knowledge that is not meaningful to them but is presented by experts in the field. In this sense, traditional development is not context- or teacher-sensitive. On the contrary, visionary professional development is about helping teachers grow in their profession and has a constructivist perspective to learning.

Richards and Farrell (2005) further differentiate the terms training and development. These authors define training as actions that teachers perform and that have an immediate impact on their contexts. In their view, training is about preparing teachers for the teaching task itself, that is, techniques that would help them cope with teaching situations such as adapting materials and grouping learners among others. Development, in contrast, involves teachers’ knowledge of themselves and of their teaching situations. Whereas training is a top-down approach to teacher education—experts decide what comprises training programs—development is bottom-up because it “often involves examining different dimensions of a teacher’s practice as a basis for reflective review” (Richards & Farrell, 2005, p. 4). Among the dimensions that Richards and Farrell address are, for example, the understanding of how students learn language and the analysis of teachers’ philosophies for language teaching.

González (2007) proposes a situated model of professional development for English language teachers. In her view, a situated model would accommodate the specific needs of English teachers in Colombia. First of all, the model proposed by the author is shaped by Kumaravadivelu’s (as cited in González, 2007) post-method pedagogy; specifically, the parameters of particularity, practicality, and possibility are called for. González implies that professional development programs should be devised for specific contexts, encourage the making of contextual theory and reflection, and take teachers’ voices into account. Second, González proposes the discussion of external and local knowledge so that teachers have the chance to critically reflect upon the former and deconstruct and (re)construct the latter. It is about making local knowledge relevant for the more global discussion of language teaching. Third, the author argues that local scholars and national authorities should engage in dialog so that there are more perspectives on the construction of situated development programs. Further, she urges that local academia be heard and taken into account so that this academia does not disappear. Finally, González’s model advocates for accepting criticisms of colonial models of professional development; critical divergent voices, she states, must be heard in the construction of a professional development model that would actually respond to the needs of Colombian English language teachers.

Richards (2011) explores ten core dimensions that, in his mind, make up the profile of exemplary English language teachers. The dimensions range from knowing the language of instruction to the capacity to derive theory from practice. Below, this article will briefly address each of the ten dimensions Richards defines.

The first dimension is called the language proficiency factor. The author explains how both native and nonnative speakers of the English language need to possess a series of skills related to how they use language. One of those skills is providing input at a level that is appropriate for learners. The second dimension is the role of content knowledge, which is divided into two: disciplinary content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge; the former is specific to language teaching and involves knowledge of the history of this field, including disciplines such as pragmatics, sociolinguistics, phonology, and syntax; the latter comprises the ability to plan curricula, reflect upon practice, and manage classroom environments. The third dimension entails teaching skills. Richards argues that these are the types of competences that teachers develop over time in professional development programs and because of reflective teaching. Richards (2011) states that “teaching from this perspective is an act of performance, and for a teacher to be able to carry herself through the lesson, she has to have a repertoire of techniques and routines at her fingertips” (p. 9). Richards argues that teaching skills are the result of teachers’ decision-making and as such should be considered in teacher training. The fourth dimension is contextual knowledge, which refers to the knowledge that teachers have about the conditions and human and material resources of the contexts in which they teach; knowing the school curriculum and policies for disciplinary issues fall into this dimension. The fift h dimension the author explores is the language teacher’s identity; this reflects the different roles that teachers are expected to display depending on school policies and even the cultures where they teach. Richards (2011) defines identity as “the differing social and cultural roles teacher-learners enact through their interactions with their students during the process of learning” (p. 14).

The sixth dimension in a teacher’s profile is referred to as learner-focused teaching. Richards argues that teacher performance can be influenced by student learning and that exemplary teachers familiarize themselves with student behavior, devise teaching practices based on this knowledge, and keep students engaged during lessons. Making the classroom a community of learning and personalized teaching are two skills that fall under the category of learner-focused teaching. Pedagogical reasoning skills is the seventh dimension the author defines; it denotes teachers’ ability to make informed choices before, during, and after class. These skills are shaped by the actions, beliefs, knowledge, and opinions teachers have of themselves, their learners and their contexts. Below are four of these skills:

1. Analyze potential lesson content (e.g., a text, an advertisement, etc.).2. Identify specific linguistic goals (e.g., in the area of speaking, vocabulary, etc.) that could be developed from the chosen content.

3. Anticipate any problems that might occur and ways of resolving them.

4. Make appropriate decisions about time, sequencing, and grouping arrangements (Richards, 2011, p. 20).

Richards argues that teachers’ philosophies should be addressed in professional development programs because they help teachers learn. Teaching philosophies are shaped by the ability to reflect upon experience and arrive at principles for second-language teaching and learning. This is the eighth dimension, called theorizing from practice. The ninth dimension involves belonging to a community of practice. The author explains how teacher communities should work together toward common goals and engage more individualistic members to share with the community at large. Lastly, professionalism is the tenth dimension, and it relates to the idea that language teachers are part of a scientific academic educational field and that, because of this, they should be familiar with what is current in the field. More importantly, Richards suggests that teachers must be critical and reflective upon themselves and their practices. Some questions for reflection leading to professionalism could be:

1. What are my strengths and limitations as a language teacher?2. How and why do I teach the way I do?

3. What are the gaps in my knowledge?

4. How can I mentor less experienced teachers? (Richards, 2011, p. 28)

Through the cycles in action research (Kemmis & McTaggart, 1988), the present study explores how a situated professional development program has an impact on the classroom performance of English language teachers. As has been explored so far in this paper, performance is far more complex than routine actions in class.

Research studies on professional development programs seem to agree upon the idea that these programs should be localized because they allow teachers to reflect upon pertinent common goals. Ariza and Ramos (2010) conducted an action research study in the same institute where the present study was developed, with a different group of ten English teachers. In their study, the researchers found that the teacher study group (TSG) they implemented allowed the participants to make connections between theory and practice; in addition, the participants thought the TSG was a space to receive colleague support for problematic areas in their own teaching contexts. Finally, the researchers concluded that the TSG helped the participants to become more reflective about their teaching practice. In Álvarez and Sánchez’s (2005) study, the researchers found that the study group they investigated helped teachers to become aware of their teaching practices and of the need to update themselves continuously. Additionally, the participants had the chance to share pedagogical ideas and improve their language proficiency. Activities in which the teachers played the role of learners were meaningful for them because they became aware of teaching issues that affect learners.

Furthermore, Sierra (2007) explains how teachers involved in a study group learned about issues having to do with teaching (e.g., what are learning strategies); they also learned theory and practice regarding research. The author states that in this study, the teachers developed research skills (developing a research proposal), critical thinking skills (questioning, arguing, and reasoning) related to the contents they studied, and collaborative skills (e.g., working in teams). The last finding in Sierra’s study was about teacher attitudes. The participants were participative and contributed to the study group; they also developed positive attitudes toward being engaged in a study group.

Finally, the findings in Cadavid, Quinchía, and Díaz’s (2009) study were divided into three categories: Participants as language learners, participants as English language teachers in elementary school, and participants as reflective practitioners. For the first category, the researchers found that the participants in the professional development program improved their communicative competence in writing; in the second category, the participants stated that they became aware of their roles as teachers and included new practices in their instruction; in the last category, the participants showed reflective skills in that they were able to critically connect theory and practice by analyzing whether it was possible to apply some of the ideas in the program to their own teaching contexts.

The Problem

Understanding the real impact of a professional development program on the day-to-day practice of English language teachers is of interest in teacher education; furthermore, basing these types of programs on the specific contexts of teachers should be addressed and studied. That is why the present study was carried out, seeking to find answers for the following research question:

• What is the effect of a professional development program on in-service English language teachers’ classroom performance in an English language institute?

The problem was identified in a diagnostic stage prior to the implementation of the program. During this stage, the following data collection instruments were used to argue for the need to develop a professional development program: a questionnaire inquiring into teachers’ needs and wants, an informal interview with the Instituto de Lenguas Extranjeras (Institute of Foreign Languages, ILEX) coordinator, one classroom observation and one semi-structured interview with each of the six participants in this research study. After the data analysis in the diagnostic stage, the five problematic areas shown in Figure 1 emerged; they later became the main areas to be covered by the professional development program.

Context

The present study was conducted at ILEX, the language institute belonging to Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira. The institute is responsible for teaching English to the student population at the university, and its curriculum includes other languages such as French, Italian, and Mandarin Chinese. In the English language curriculum, the ILEX includes sixteen courses ranging from elementary to upper-intermediate English.

The ILEX seeks to help teachers to develop professionally by means of workshops that address relevant issues in language teaching. The professional development program derived from this study was another strategy to help ILEX teachers to continue growing as professionals.

Method

The present study relied upon the cycles of action research methodology as proposed by Kemmis and McTaggart (1988). All workshops in the program were analyzed and improved upon based on the data collected. The techniques for data collection used while the program unfolded were questionnaires on each of the workshops, two classroom observations and two semi-structured interviews with each of the participants, and a researcher’s journal. The role of the researcher was that of participant observer because he was the one responsible for guiding the program workshops.

Six novice in-service English language teachers were involved in the study. At the time the research was conducted, they were English teachers at ILEX as well as students of a language teaching program (Licenciatura en Lengua Inglesa, Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira). When the professional development program began, all six in-service teachers had had teaching experience of less than six months. The questionnaire was implemented to evaluate each weekly workshop; the classroom observations as well as the semi-structured interviews took place after the third and the sixth workshops; finally, entries in the researcher’s journal were written every week, after each of the workshops.

Data analysis followed a grounded theory approach (Glasser & Strauss as cited in Birks & Mills, 2011). The results from each of the instruments were grouped, and overlapping areas were identified across all four data collection techniques. Broad categories emerging from all four instruments were identified so as to answer the research question for this study.

Findings

The findings from this study were three major ones, with corresponding results for each. First, information from all four data collection techniques explained the direct impact of the professional development program on the teachers’ classroom performance. Second, based on the data analysis, the teachers demonstrated awareness of their teaching and classroom performance. Finally, the data collected explain how the professional development program represented a reason for improvement among the six in-service English language teachers.

On Classroom Performance

The first group of findings reflects the teachers’ changing performance while teaching in class. This article will now refer to specific areas that seemed to be improvements between the diagnostic stage both prior to the professional development program and while it was being conducted. The data come mostly from class observations and represent what the teachers did well according to contemporary principles of language teaching. The findings show some insights into teachers’ views of language and the ways they operationalized these views in their teaching; additionally, there is some indication of growing attention to learners’ needs and motivations.

The results across all four instruments reflected a change in the theory of language the teachers displayed in their lessons. Before the program, the way they viewed English was structural. However, because of their development in the program, the teachers developed a more holistic view of language and proposed activities in which students could interact with each other communicatively and meaningfully. Overall, their lessons went from being an accumulation of structures to real communication as a teaching principle.

Sample data from one questionnaire that evaluated one of the program workshops:

A. From now on, in my teaching, I should not:

In-service Teacher 1: focus on the structure but on the meaning.

In-service Teacher 2: focus so much on grammar and structure.B. From now on, in my teaching, I should:

In-service Teacher 4: implement more communicative activities.

In-service Teacher 5: make clear if the activities or tasks are really communicative or not.

The following data are taken from a class observation’s transcription. They first show two of the evaluation criteria for the observed lesson, along with corresponding comments. The other extract comes from the general feedback given to the in-service teacher in the form of improvements (or strengths during the lesson).

1. Lesson focuses more on meaning than on structure.

Yes _X_ No ___When students were filling in the table with their classmate’s daily routine, they were using grammar as meaning, not as cold inert structure! Good thing they did this.

2. Grammar is used functionally or communicatively (to express meaning) and not as an end in itself.

Yes _X_ No ___Same as above! The fact they used it to do something makes grammar functional…keep this key principle in mind for every lesson you teach. They learn something and learn how to do something with what they learn.

Improvements Between the Diagnostic and Action Stages

• Students use language structures meaningfully and to interact with others.

• Language at the oral level is then used for a writing product, which means activities are coherent somehow.

• If there was a focus on structure, this structure(s) was used communicatively.

The way the in-service teachers taught grammar followed a principled approach. Rather than planning explicit grammar activities, they proposed discovery ones in which students could identify the grammar items by themselves; therefore, grammar was taught inductively. Additionally, the grammar the teachers addressed in lessons was used by students in communicative interactional activities, which agrees with the idea of meaningful English explained in the previous finding. Following is an extract from a different class observation.

13. Grammar is addressed based on current agreements on the matter: taught inductively and deductively, contextualized, with a focus on meaning, and communicatively.

Yes _X_ No___Yes, the house description was perfect to make sense of all the issues we have discussed in grammar teaching, was it not? They had input to discover, used grammar meaningfully to describe their own houses, and then focused on emerging mistakes during the feedback session.

Improvements Between the Diagnostic and Action Stages

Again, your grammar teaching is improving continuously, and the pacing for this is consistent. Now you are teaching with an approach that has both inductive and deductive teaching. Congratulations!

The lessons that the in-service teachers taught were coherent. They made sure that each procedure in an activity would be articulated. This skill followed three stages. First, activities had a beginning, in which teachers introduced a topic, prepared students, modeled behavior, and others. Second, teachers were attentive to keeping students engaged on a core interactional or comprehension task. Finally, the last part of each activity, or the post-task, served as feedback for the task students had just done. Topics were used as organizing principles during lessons, which made them appear coherent as well.

The following data were taken from a class observation protocol that was used to observe one of the in-service teachers.

8. Activities (or tasks) have a clear structure of beginning, middle, and end.

Yes _X_ No___Yes, activities were phased coherently. This was perfect for students to recycle key language from the lesson and to use it well. Trial and error occurred and therefore learning and acquisition took place. You prepared students for tasks, had them do a core task and then corrected it to focus on language.

Improvements Between the Diagnostic and Action StagesLesson coherence: between eliciting parts of a house, describing your own as support and listening activity, and the students talking about their own house, coherence was high. Good you did this!

The teachers implemented current methodologies for language teaching. Aligned with the ideas in the previous paragraphs, the teachers taught lessons based on the pillars of communicative language teaching: They gave learners the chance to interact meaningfully with each other, used authentic materials, and referred to communicative competence as a goal in their teaching. Task-based language teaching was evident when the teachers proposed tasks for real-life purposes in which language was used as a means to an end. Lastly, the teachers used content-based instruction as a way to help the learners learn something through the English language. The following samples are also taken from an observation protocol.

5. The in-service teacher includes authentic content in the materials used in class.

Yes _X_ No ___Information about ratings is authentic language which is simple to learn. And yet it is useful!

When you were presenting the ratings, they had descriptions. This was perfect for them to interact with simple authentic language. You shouldn’t have read it yourself, though. It would have been a great reading activity.

EDITED: When they associated ratings and movies, there was some kind of meaningful language interaction going on.

In the case of movie treats, most content depended on your presentation of them. How to do this more learner-centered and facilitating teaching?

The principle here:If they are exposed to language that they are learning, what are they learning it for? In this activity, you did have that principle in mind.

While lessons developed, the teachers were attentive to students’ needs and motivations. They acted upon students’ needing explanations, examples, clear instructions, and a helping hand during core tasks. They also activated their students’ learning strategies so that they could approach tasks more successfully. The motivation students showed was evident when they volunteered to participate and also while they were engaged in meaningful communicative activities in which they were asked to interact with each other.

9. The in-service teacher supports learners in all these stages using varied techniques to do so.

Yes _X_ No___Yes, this did happen when you modeled by asking questions about how you wanted them to describe the displayed pictures.

12. Motivation is activated and maintained during lesson.

Yes _X_ No___You did use extrinsic motivation for the treasure hunt task. The hunt seemed intrinsically motivating because the students did need to be quick or use their understanding to accomplish the task. And remember that one of the features of motivated students is that they are goal-oriented.

On Awareness of Teaching and Classroom Performance

The second group of findings shows the areas where the teachers felt there were improvements in their teaching in general and, specifically, in their classroom performance. The teachers affirmed that because of the professional development program, they gained deeper awareness in these areas: grammar teaching, implementation of current methodologies for language teaching, the importance of student motivation, learner styles and learning strategies, and coherence for classroom activities. In this case, the data come from the interviews during the professional development program.

The teachers stated that there was a noticeable improvement in grammar teaching; specifically, they argued that their perspectives on the topic progressed from a structure-only strategy to one in which students had the chance to discover and use grammar meaningfully. Rather than teaching grammar deductively, the teachers said they would teach it inductively as they helped students discover grammar rather than analyze it as a first approach to learning it. The following extract from an interview depicts an in-service teacher’s improvement in his/her approach to grammar teaching.

I’ve seen how the grammar is implicitly taught, or no, learned! I know how they get the grammar without, and I don’t have to be on the board, explaining a lot, always explaining. No! They get the grammar and then we clarify some things and that’s it. So I’m really happy about that. It has been an improvement, one of the biggest ones! Because, um, well before you know, um, sometimes I started with the grammatical thing and everything but now, I start with the task, which involves, um, I mean, um, discovery and eliciting. I love that because they learn faster, even faster than when you explain on a board and everything.

Additionally, the teachers stated that they implemented ideas from current language teaching methodologies such as task-based language teaching and content-based instruction. Even though the teachers explained that they needed to further explore the implementation of such methodologies, for them it was something that they learned and practiced in the professional development program and began to include in their lessons.

I’ve been applying almost all the methodologies, no! All the methodologies you taught us, and I think they are awesome, and I didn’t do that before. Now I’m doing it and am seeing the results, and I’m really happy with that. Task-based activities, content-based activities, um, I am in love now with those methodologies because they are working in…amazingly. I mean, I love it.

Furthermore, the issue of motivation was something the teachers became more aware of. The teachers argued that they took into consideration their students’ needs and interests, which they later turned into classroom activities. The conclusion here is that the teachers were able to operationalize the construct and make it applicable by means of interviews with students and small surveys to inquire into their needs and interests.

I’m also working with motivation issues. Em, I think what I’ve seen in this course that I, that I’ve applied in the classroom in terms of motivation it’s been, it’s been awesome. I mean, I’m working on that and it’s really working. The motivation of the students have increased a lot. I can see the results. First of all, I’m telling them the aims of the class; also I’m telling them why is English important now. Using examples, using, um, asking them critical thinking questions such as, mmm, that has to deal with their futures. Ummm, what else? I think I’m just being friendly with them and telling them that this is not an obligation but something good for them.

One last major change that the teachers noticed in their instruction was coherence in lessons. They specified that their lessons were more structured and logical because the activities held cohesion among steps and led to desired goals during lessons. According to the teachers, they planned tasks that had a beginning, a middle, and an end.

This was one of the biggest changes and improvement I could notice, the way I teach now comparing to the old way which was, ummm, sometimes unstructured and lacked coherence in many cases, I realized this by reflecting upon my experience before and after the PDP.

On the Professional Development Program as a Reason for Improvement

In this last finding, I will refer to the reasons that likely caused the changes in the six teachers’ performance and awareness in English language teaching. I will support these findings on the data collected while developing the professional development program.

All of the workshops combined theory and practice. The teachers had the opportunity to look at theoretical underpinnings and analyze them by observing videoed and live lessons, planning activities to be used in their lessons, and receiving feedback from peers and the program’s tutor. Additionally, the program included experiential learning activities in which the teachers played the role of learners first and then evaluators of what they had experienced as language learners. This also helped them to contextualize theory. Finally, the program incorporated talks by experts; during these exercises, the teachers had the opportunity to hear about and discuss ideas for language teaching from experienced peers. The excerpt below, taken from a journal entry, shows what teachers did to combine theory and practice.

What went well?

The experiential activity: During this workshop, I had an experienced teacher guide the in-service teachers through a listening activity about a bad hairdressing experience. First of all, this was an activity in which the in-service teachers could connect theory and practice by means of a hands-on task. I think they could identify the stages in a listening activity and how those stages are related to what we have emphasized on a lot during the workshop: organized coherent activities, with a clear purpose in mind, etc. Second of all, this activity went well because of the guest teacher. He walked them through the listening activity and was keen on preparing them for listening, which, as one of the in-service teachers told me, was good for him to realize that before the actual listening, students need quite some support.

The expert talk: For this workshop, besides the guest teacher, I invited other two teachers to hold a conversation with the in-service teachers about teaching listening. In total, there were three experts interacting with them. The expert talk occurred after the experiential learning activity, so this was perfect to tie loose ends in relation to teaching listening. The in-service teachers could get explicit ideas on teaching listening from the guest teachers, so I think this could have helped consolidate principles. In the workshop, I also asked the guests to get in groups with the in-service teachers. What this caused was a lively discussion between the guests and the in-service teachers, and it was the perfect wrap-up for the expert talk. They had the chance to react to the discussion previously held, and they could talk about their own experience. All this led to a successful section in this workshop.

The practical activity: The in-service teachers prepared a listening activity for a near future lesson. After 10 minutes preparing it, I discussed the activity with them. This definitely went well because the in-service teachers could relate theory and practice. Everything happening in this workshop could be put into practice thanks to the listening activity they planned. Also, my job as an educator was key for them to make the connection theory-practice. I was able to help the in-service teachers make sense of everything they had learned in the workshop and through their own reading of the material.

Retrospective reflection was a major enterprise during the program and one that helped the teachers to improve their teaching. This type of reflection occurred when the teachers looked at the ideas that they planned during the program’s workshops and that they implemented in their lessons. Because there was follow-up, each workshop in the program capitalized on something the teachers had just implemented.

I think just by, uh, encouraging the fact that, uhm you know, of constantly reflecting, you know, on, your, uh, in that case, weekly sessions, um, the lessons I teach on Saturday. Um, well just the fact that you were constantly reflecting on them. Obviously, in a way you have to really improve. Not have to, but it is something that obviously you feel that you need to do. So, for example, when I would give my lesson on Saturday, and then we would have the course on Thursday, and it was about a certain, you know, concept or something, and I would reflect if I have done it, if I should do it better, how should I do it better? So, I would be constantly reflecting, you know, on what I already know and how I can improve that, and yeah.

Finally, a key aspect to helping the teachers improve their teaching performance was my interaction with them as a tutor. Because of a number of strategies that I implemented during the professional development program, I was able to help the teachers connect theory and practice. First, while the teachers were doing a practical task during workshops (which they would later apply in their lessons), I talked to them about what they wanted to do and asked them questions to help them reflect prior to implementing their ideas and to make them use theory explicitly. Second, because I observed each teacher twice, I gave them feedback before and after the lessons I observed. Each teacher received the feedback on his or her lesson plans and on the observation protocol for this study. Finally, the teachers and I conversed about their teaching ideas and reflected on them, specifically, whether they went well or not as well and why; from these reflections, I would ask them to come to their own conclusions about language teaching and learning. The following are two samples taken from two different entries in two different workshops. They are about ideas the teachers had planned in the workshops and intended to implement later on.

Sample 1

While I was interacting with the in-service teachers, I noticed that they stay at a grammatical-functional phase of communicative language teaching (CLT). For example, they showed me they would ask students to interact with teacher or others based on questions such as: What’s your name? What do you do? While this is communicative, it is not aligned with task-based language teaching (TBLT) or content-based instruction (CBI), for example. It is a stand-alone activity. When interacting with the in-service teachers, many of them realized this can (and should) be part of a broader activity which leads somewhere.

Another example the teachers gave me was about nationalities. They told me they have students ask each other where they are from: students have a different nationality and say, for instance: “I am from Japan.” I explained to the in-service teachers that this is functional but not communicative unless you had a group of students from different countries.

In conclusion, the in-service teachers may have developed a deeper understanding of what it means to teach within a communicative approach in TBLT and CBI.

Why? I believe that the fact that the in-service teachers interacted with me was key to help them refocus. I personally felt during this second workshop that when I talk to the in-service teachers, I can detect what their present knowledge is and can complement it. They may have read for the workshop but they need to be guided on how to make theory more practical/meaningful for them.Sample 2

The in-service teachers prepared a listening activity for a near future lesson. After 10 minutes preparing it, I discussed the activity with them.Why?

This definitely went well because the in-service teachers could relate theory and practice. Everything happening in this workshop could be put into practice thanks to the listening activity they planned. Also, my job as an educator was key for them to make the connection theory-practice. I was able to help the in-service teachers make sense of everything they had learned in the workshop and through their own reading of the material.

The findings in this study are similar to those in Álvarez and Sánchez’s (2005) study in the sense that in both research studies, teachers became aware of their teaching practices. Moreover, the authors’ study reported positive results from having teachers perform activities as students, which was another positive result in the present study. Similar results are reported in Sierra’s (2007) study as well. In this case, the researcher found that in the study group for her study, the teachers became aware of teaching issues such as knowing what learning strategies are. In the present study, the findings indicate that the in-service teachers became aware of issues such as grammar teaching and student motivation. Finally, there is a relationship between the findings in this study and those in Cadavid, Quinchía, and Díaz (2009). In their study, the participants in the professional development program included new practices in their teaching, which also happened in the present study, in which the six in-service teachers also implemented new, practical ideas in their teaching. Furthermore, in both studies, the teachers connected theory and practice by critically analyzing whether they were applicable to their contexts.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Professional development programs do have an impact on in-service teachers and their classroom performance, and this is possible especially when program developers take into account the suggestions given by scholars in the field. Provided that these programs consider teachers’ needs, knowledge, skills, and experiences, there is a strong likelihood of positive results. Based on these perspectives, it is suggested that those involved in designing and implementing professional development programs for language teachers conduct a careful needs analysis before implementation; this needs analysis should take into account not only what the teachers do (well or badly) but also what they know, what they would like to know, and what their experiences and beliefs for language teaching and learning are. After this analysis, designers can use the collected information to capitalize on implementation.

Theory and practice in professional development programs have a reciprocal relationship, which can have a positive impact on teachers and their practice. These programs should include opportunities for teachers to make sense of theory and to criticize and use it meaningfully for classroom contexts. The recommendations arising from this idea are four. First, professional development programs should include theoretical input that responds to the needs and wants identified in the needs analysis prior to starting a program. Second, these programs should include explicit activities for teachers to discuss issues around theoretical underpinnings: Whether they can be applied, whether they need to be adapted, and so forth. Third, teachers in this program should be encouraged to explicitly use the theory they study in practical realizations such as lesson plans, class observations, and the planning and execution of classroom activities. Teachers benefit from being asked to use theory this way and to reflect upon it. Lastly, activities that combine theory and practice in professional development programs, especially ones that address planning and executing teaching ideas, should have follow-up sessions for reflection. Teachers and teacher educators, or collaborators (Freeman, 1989), should reflect prior to and on action to see in what ways the program is having an impact on teachers.

Teacher educators play a vital role during the implementation of professional development programs. They benefit from having someone help them make sense of theory and their practice, who can articulate activities that help them reflect upon teaching issues and who can guide them to see what they do well and not as well. As Freeman (1989) proposes, a teacher educator should not be an expert but a collaborator who can make teachers think critically upon their own teaching. All things considered, teacher educators must ensure that they do have close contact with each and every one of the participants in professional development programs. Face-to-face discussions can help both parties to more effectively evaluate their individual processes; additionally, having a systematic process of class observation can help the teacher educator to monitor a teacher’s progress while he or she is in a professional development program. A system for class observations should have three phases: first, teachers should send their lesson plans so the educator can give feedback before the lesson; second, the educator can observe the lesson with the corresponding protocol; and finally, teachers should receive feedback on their lessons, perhaps by means of the completed observation protocol.

References

Álvarez, G., & Sánchez, C. (2005). Teachers in a public school engage in a study group to reach general agreements about a common approach to teaching English. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 6(1), 119-132.

Ariza, J., & Ramos, D. (2010). The pursuit of professional development through a teacher study group (Unpublished master’s thesis). Universidad de Caldas, Manizales.

Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2011). Grounded theory: A practical guide. London, UK: Sage Publications.

Cadavid, I. C., Quinchía, D. I., & Díaz, C. P. (2009). Una propuesta holística de desarrollo profesional para maestros de inglés de la básica primaria [A holistic profesional development proposal for elementary school English teachers]. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 14(21), 133-158.

Díaz-Maggioli, G. (2004). Teacher-centered professional development. Alexandria, VA: ASCD Publications.

Freeman, D. (1989). Teacher training, development, and decision making: A model of teaching and related strategies for language teacher education. TESOL Quarterly, 23(1), 27-45.

González, A. (2007). Professional development of EFL teachers in Colombia: Between colonial and local practices. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 12(18), 309-332.

Hopkins, D. (1995). A teacher’s guide to classroom research. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

Kemmis, S., & McTaggart, R. (1988). The action research reader (3rd ed.). Victoria, AU: Deakin University Press.

Richards, J. C. (2011). Competence and performance in language teaching. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Richards, J. C., & Farrell, T. S. C. (2005). Professional development for language teachers: Strategies for teacher learning. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Sierra, A. M. (2007). Developing knowledge, skills, and attitudes through a study: A study on teachers’ professional development. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 12(18), 277-306.

Villegas-Reimers, E. (2003). Teacher professional development: An international review of the literature. Paris, FR: UNESCO, International Institute for Educational Planning.

Wilde, J. (2010). Guidelines for professional development: An overview. In C. J. Casteel & K. G. Ballantyne (Eds.), Professional development in action: Improving teaching for English learners (pp. 5-11). Washington, DC: National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition. Retrieved from http://www.ncela.gwu.edu/files/uploads/3/PD_in_Action.pdf

About the Author

Frank Giraldo is a teacher educator and English language teacher. He holds an MA in English didactics from Universidad de Caldas and works for Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira (Colombia), at the Institute of Foreign Languages (ILEX) - and the B.Ed in English. He is interested in teacher education through professional development, curriculum design, and language testing, assessment, and evaluation.

References

Álvarez, G., & Sánchez, C. (2005). Teachers in a public school engage in a study group to reach general agreements about a common approach to teaching English. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 6(1), 119-132.

Ariza, J., & Ramos, D. (2010). The pursuit of professional development through a teacher study group (Unpublished master’s thesis). Universidad de Caldas, Manizales.

Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2011). Grounded theory: A practical guide. London, UK: Sage Publications.

Cadavid, I. C., Quinchía, D. I., & Díaz, C. P. (2009). Una propuesta holística de desarrollo profesional para maestros de inglés de la básica primaria [A holistic profesional development proposal for elementary school English teachers]. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 14(21), 133-158.

Díaz-Maggioli, G. (2004). Teacher-centered professional development. Alexandria, VA: ASCD Publications.

Freeman, D. (1989). Teacher training, development, and decision making: A model of teaching and related strategies for language teacher education. TESOL Quarterly, 23(1), 27-45.

González, A. (2007). Professional development of EFL teachers in Colombia: Between colonial and local practices. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 12(18), 309-332.

Hopkins, D. (1995). A teacher’s guide to classroom research. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

Kemmis, S., & McTaggart, R. (1988). The action research reader (3rd ed.). Victoria, AU: Deakin University Press.

Richards, J. C. (2011). Competence and performance in language teaching. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Richards, J. C., & Farrell, T. S. C. (2005). Professional development for language teachers: Strategies for teacher learning. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Sierra, A. M. (2007). Developing knowledge, skills, and attitudes through a study: A study on teachers’ professional development. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 12(18), 277-306.

Villegas-Reimers, E. (2003). Teacher professional development: An international review of the literature. Paris, FR: UNESCO, International Institute for Educational Planning.

Wilde, J. (2010). Guidelines for professional development: An overview. In C. J. Casteel & K. G. Ballantyne (Eds.), Professional development in action: Improving teaching for English learners (pp. 5-11). Washington, DC: National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition. Retrieved from http://www.ncela.gwu.edu/files/uploads/3/PD_in_Action.pdf

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Selma Deneme, Handan Çelik. (2017). Facilitating In-Service Teacher Training for Professional Development. Advances in Higher Education and Professional Development. , p.1. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-1747-4.ch001.

2. Nicole King, Kim H. Song, Gregory Child. (2023). Virtual professional development project on secondary teachers’ awareness of race, language, and culture. Language Teaching, 56(1), p.137. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444821000446.

3. Rudha Widagsa, Fatiha Senom, Fonny Dameaty Hutagalung. (2025). Teaching out-of-field: exploring the non-specialist English language teachers’ knowledge base and practices. Cogent Education, 12(1) https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2025.2514914.

4. Selma Deneme, Handan Çelik. (2018). Teacher Training and Professional Development. , p.1389. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-5631-2.ch063.

5. Dan Wan, Rongfang Gu, Claire McLachlan. (2020). WITHDRAWN—Administrative Duplicate Publication: New kindergarten teachers’ career development trajectories in China: A problem-solving perspective. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, , p.183693912093600. https://doi.org/10.1177/1836939120936001.

6. Hugo Parra-Sandoval, Marielsa Ortiz-Flores , Yannett Arteaga-Quevedo, Yaneth Ríos-García. (2024). Los formadores de profesores en lengua, matemáticas y ciencias naturales en Iberoamérica. Estado del arte. Magis, Revista Internacional de Investigación en Educación, 17, p.1. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.m17.fplm.

7. Hanife Taşdemir, A. Cendel Karaman. (2022). Professional development practices of English language teachers: A synthesis of studies published between 2006 and 2020. Review of Education, 10(1) https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3350.

8. Balachandran Vadivel, Ehsan Namaziandost, Abdulbaset Saeedian. (2021). Progress in English Language Teaching Through Continuous Professional Development—Teachers’ Self-Awareness, Perception, and Feedback. Frontiers in Education, 6 https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.757285.

9. Michel Riquelme-Sanderson, Priscila Riffo-Salgado, Neil Arias Silva, Loreto Aliaga Salas, Nancy Mitchell, Juan Caviedes-Ramos, M. Alejandro Urzúa Núñez, Eric Gómez Burgos, Franco Valdés Silva, Luigina Brachitta, Nykoll Pinilla-Portiño, Gloria Romero, Jocelyn Cuitiño. (2026). Professional development and learning for Chilean teachers and researchers through podcasts: The case of RICELT. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 20(1), p.60. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2025.2531030.

10. Dan Wan, Rongfang Gu, Claire McLachlan. (2020). New kindergarten teachers’ career development trajectories in China: A problem-solving perspective. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 45(3), p.228. https://doi.org/10.1177/1836939120936008.

11. Marta Isabel Barrientos-Moncada, Natalia Andrea Carvajal-Castaño, Hernán Santiago Aristizabal-Cardona. (2023). EFL Teacher Professional Development Needs: Voices from the Periphery. HOW, 30(2), p.92. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.30.2.762.

12. C. Maricela Cajamarca I, Veronica Herrera, Daysi Karina Flores. (2023). Having Fun and Teaching Learning English Outreach Project Evaluation UNAE Ecuador: A Quantitative Study in Virtual Education. 2023 XIII International Conference on Virtual Campus (JICV). , p.1. https://doi.org/10.1109/JICV59748.2023.10565712.

13. Ahmed ElSayed Abouelanein, Mohamed Hossni. (2023). BUiD Doctoral Research Conference 2022. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering. 320, p.47. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-27462-6_5.

14. Le Van Canh. (2022). Handbook of Research on Teacher Education. , p.333. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-9785-2_17.

15. Adlane Deeb El Afi. (2019). The impact of professional development training on teachers’ performance in Abu Dhabi Cycle Two and Three schools. Teacher Development, 23(3), p.366. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2019.1589562.

16. Santosh Kumar Mahapatra. (2020). Impact of Digital Technology Training on English for Science and Technology Teachers in India. RELC Journal, 51(1), p.117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688220907401.

17. Elmaziye Özgür Küfi. (2022). A Retrospective Evaluation of Pre-Pandemic Online Teacher Learning Experiences. Sage Open, 12(1) https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221079907.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.