From Awareness to Cultural Agency: EFL Colombian Student Teachers’ Travelling Abroad Experiences

De la concientización a la agencia cultural: las experiencias en el extranjero de futuros profesores de inglés

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v17n1.39499Keywords:

EFL pre-service teachers, ethnocentrism, ethno-relativism, intercultural learning, work, study, and residence abroad (en)aprendizaje intercultural, etnocentrismo, etnorelatividad, profesores en formación de inglés como lengua extranjera, trabajo, estudio y residencia en el extranjero (es)

Colombian English as a foreign language student teachers’ opportunities to grow as educators through international sojourns do not usually subsume the traditional study and residence abroad goal. This was the case for our participants who engaged mainly in working abroad with study being ancillary. Fifty student teachers from two public universities reported how their international sojourn bolstered their intercultural learning. Three different programs, disconnected from participants’ academic institutions, became vehicles for their experiences abroad. Surveys and interviews reveal that participants’ origin, selected programs, and contextual circumstances influenced their intercultural learning. As a result, intercultural development gravitated towards awareness of intercultural patterns, critical reading of culture, and pre-service teachers’ repositioning to build cultural agency. Implications suggest the need to connect traveling abroad programs to undergraduate curricula.

PROFILE

Issues in Teachers' Professional Development

Vol. 17, No. 1, January-June 2015 ISSN 1657-0790 (printed) ISSN 2256-5760 (online)

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Viafara González, J. J., & Ariza Ariza, J. A. (2015). From awareness to cultural agency: EFL Colombian student teachers’ travelling abroad experiences. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 17(1), 123-141. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v17n1.39499.

From Awareness to Cultural Agency: EFL Colombian Student Teachers’ Travelling Abroad Experiences

De la concientización a la agencia cultural: las experiencias en el extranjero de futuros profesores de inglés

John Jairo Viafara González*

J. Aleida Ariza Ariza**

Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia, Tunja, Colombia

*viafarag@email.arizona.edu

**aleariza1971@gmail.com

This article was received on August, 13, 2013, and accepted on July 31, 2014.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Colombian English as a foreign language student teachers’ opportunities to grow as educators through international sojourns do not usually subsume the traditional study and residence abroad goal. This was the case for our participants who engaged mainly in working abroad with study being ancillary. Fifty student teachers from two public universities reported how their international sojourn bolstered their intercultural learning. Three different programs, disconnected from participants’ academic institutions, became vehicles for their experiences abroad. Surveys and interviews reveal that participants’ origin, selected programs, and contextual circumstances influenced their intercultural learning. As a result, intercultural development gravitated towards awareness of intercultural patterns, critical reading of culture, and pre-service teachers’ repositioning to build cultural agency. Implications suggest the need to connect traveling abroad programs to undergraduate curricula.

Key words: EFL pre-service teachers; ethnocentrism; ethno-relativism; intercultural learning; work, study, and residence abroad.

Las oportunidades de crecimiento que futuros docentes colombianos de inglés obtienen al participar en programas para viajar al exterior, usualmente no reflejan las metas en el área de residencia y estudios en el extranjero. Un porcentaje alto de los participantes reportaron experiencias de trabajo, relegando sus objetivos académicos a un segundo plano. Cincuenta estudiantes de dos universidades públicas, quienes viajaron con tres programas no conectados oficialmente con sus universidades, reportan cómo su experiencia fortaleció su aprendizaje intercultural. Encuestas y entrevistas develaron el origen y perfil de los participantes, los programas seleccionados y circunstancias contextuales como factores en su aprendizaje. Además, los participantes identificaron patrones interculturales, lograron una lectura crítica de la cultura y un reposicionamiento en la construcción de agencia cultural. Las implicaciones discuten la necesidad de conectar estos programas de viaje con los currículos de pregrado.

Palabras clave: aprendizaje intercultural; etnocentrismo; etnorelatividad; profesores en formación de inglés como lengua extranjera; trabajo, estudio y residencia en el extranjero.

Introduction

The realm of contexts for the exploration of foreign language learning has expanded as globalization and technology attract learners with the promise of more opportunities to develop their communicative competences. In the last decades, travelling abroad has become one the most desired options for university learners to acquire and develop foreign language skills and knowledge of the target culture. Likewise, in Colombia, an increasing number of university students from various fields embark on programs to travel, mainly to the United States to learn English.

The proliferation of these experiences around the world has led to the development of study and residence abroad into a research field in itself. Within the existing published research in this area, students from the US and Europe travel to Central and South American countries to engage in study and residence abroad experiences (Marx & Pray, 2011; Petras, 2000; Pray & Marx, 2010; Santamaría, Santamaría, & Fletcher, 2009; Sharma, Aglazor, Malewski, & Phillion, 2011).

However, Latin American students are rarely the focus of studies when they travel to the US and Europe. Thus, the research published in this field does not substantially represent these sojourners. In this regard, this study seeks to expand the focus of research to include Latin American countries, providing information that higher education institutions in the region can employ to take a critical stance about the impact of these programs on students’ education. Additionally, this inquiry looks at the US as a host country for the target population.

This article describes our examination of English as a foreign language (EFL) pre-service teachers’ professional preparation in connection with their experiences abroad. In particular, we seek to uncover what student-teachers’ experiences abroad reveal about their construction of their intercultural competence. The next section reviews concepts in the study abroad field and the development of intercultural competence, as well as research conducted in the field.

Literature Review

Study Abroad

The long tradition of studying abroad dates back to the 1600s. At that time, Finnish students willing to enroll in post-secondary educational institutions travelled to Sweden where universities had already been founded (Cushner & Karim, 2004). University involvement in study abroad programs has continued to the present day. In nations like the US and the UK, universities organize student trips and integrate study and residence abroad into their curriculum (Coleman, 1997).

Since study abroad programs had their origin in universities, one might think that only academic interests have guided the configuration of these programs. However, Cushner and Karim (2004) point out that this has not always been the case. Religious, private, nonprofit, and commercial institutions play a prominent role in this field by arranging students’ overseas sojourns through their programs which might not be associated with any academic institution.

In Colombian universities, at least in the two target institutions in this study, the companies involved in participants’ experiences abroad exhibited a commercial nature. Student teachers either contacted companies which function independently from their universities or individuals with no official connection with universities and programs. There was no institutional support from their universities to participate in the experiences.

These companies usually offer job opportunities with much less emphasis placed upon educational objectives. Though some of the programs might require that all students take a course in a college or university, this is the exception, not the rule. There is a separation between educational institutions and companies, and an emphasis on the commercial nature of travelling abroad programs.

In this sense, regarding the Colombian context, participants’ work abroad, which might include formal study, informal study, or none at all, and its detachment from the universities, complicates the traditional definition of these experiences as “study and residence abroad” with an emphasis on “study.” Thereby, we propose a definition that more effectively reflects the essence of our participants’ experiences. Study abroad in our work denotes the wide variety of educational options: formal and informal, provided and self-pursued, and short and long within the context of participants’ enrollment in travelling abroad in connection with working assignments.

Despite differences, Colombian students, as other university students around the world, usually enroll in travelling abroad programs in order to acquire “‘culture based’ international education” (Engle & Engle, 2003, p. 4). The following paragraphs review the main tenets and models underpinning the development of intercultural communication.

The Development of Intercultural Knowledge, Attitudes, and Competences

Scholars in diverse fields as anthropology (Camilleri, 2002), social psychology (J. M. Bennett, 2008), study abroad (Byram, 1997), foreign and second language learning (Fantini, 2009), and international education (Deardorff, 2008) have become interested in the development of intercultural communication, attitudes, skills, and competences. From the various models these scholars propose to understand intercultural development, and the most well-known and influential conceptualizations stem from Byram and J. M. Bennett.

Byram (1997) defines intercultural competence (IC) as attitudes in relation to

readiness to suspend disbelief and judgment with respect to others’ meanings, beliefs and behaviors and a willingness to suspend belief in one’s own meanings and behaviors, and to analyze them from the viewpoint of the others with whom one is engaging. (p. 34)

For J. M. Bennett (2008), the abilities necessary for ICs are of paramount importance, thus she defines IC as, “a set of cognitive, affective, and behavioral skills and characteristics that support effective and appropriate interaction in a variety of cultural contexts” (p. 97).

These authors encourage a focus on the development of attitudes of openness towards an honest but respectful critical analysis of L1 and L2 cultures in order to gain knowledge and understanding in the search for tolerance and respect for diversity. In order to acquire the required broad-mindedness to act inter-culturally, one must shape his or her intellectual critical and reflective abilities, so that the chances to develop negative affective and emotional states towards others and one’s culture decrease.

M. J. Bennett’s (1993) developmental model of intercultural sensitivity (DMIS) is associated with a social psychology tradition and attempts to explain an individual’s evolution from ethnocentric to ethno-relativist attitudes in six stages. Denial, defense, and minimization represent sequential stages of ethnocentrism while moving through the next three stages, acceptance, adaptation, and integration represent ethno-relativism.

Byram’s (1997) model, rooted in the field of language learning, was appropriately named intercultural communicative competence (ICC). The intercultural speaker, the center of Byram’s model, enters the communicative scene with previously acquired knowledge and attitudes which she or he continues developing in interactions with speakers from other cultural and linguistic backgrounds. The ideal intercultural attitude emerges through the relativization of beliefs, behaviors, and meanings which, in turn, lead to valuing others’ cultural expressions. In Byram’s model, knowledge and attitudes aggregate to the procedural perspective of skills.

Interculturally competent speakers need to be able, on the one hand, to interpret cultural manifestations and connect these expressions between cultures and, on the other hand, to discover cultural meanings, which often occur through interaction. The development of reflective attitudes, which can be enhanced by participating in educational experiences, encourages intercultural growth. In this case, teachers guided by their educational ideologies can integrate political and critical frameworks to shape students’ intercultural skills (Byram, 1997).

Intercultural Competence and Study Abroad: What Research Reveals

A review of studies targeting pre-service teachers who enrolled in long-term study1 abroad experiences demonstrates an increase in intercultural sensitivity (Cushner & Mahon, 2002; Medina-López-Portillo, 2004). However, short-term experiences also benefit participants (Anderson, Lawton, Rexeisen, & Hubbard, 2006; Pence & Macgillivray, 2008; Sharma et al., 2011).

Among the multiple variables which shape pre-service teachers’ intercultural learning, researchers have identified the complexity of experiences (Jackson, 2008); direct contact with people and contexts (Medina-López-Portillo, 2004; Williams, 2005), pre-, while, and post-orientation (Jackson, 2008; Medina-López-Portillo, 2004), and proficiency in the target language (Medina-López-Portillo, 2004). Other variables include pre-service teachers’ metacognitive abilities to perceive and understand their changing attitudes, the relevance and dynamics of these processes, and the role that their critical reflection plays in their growth (Cushner & Mahon, 2002; Jackson, 2008; Sharma et al., 2011).

In the surveyed studies, pre-service tea-chers’ intercultural competence indicates their transformation from ethnocentric to more ethno-relative attitudes. In this vein, Cushner and Mahon (2002); Larzén-Östermark (2011); Pence and Macgillivray (2008); and Sharma et al. (2011) found that pre-service teachers questioned their perceptions, creating options to build and negotiate new understandings of themselves and the world around them.

This transformation results in a better appreciation and respect for cultural diversity (Jackson, 2008; Lee, 2009; Medina-López-Portillo, 2004; Osler, 1998), which enhances the development of empathy and confidence (Cushner & Mahon, 2002) and the readiness to solve misunderstandings and reduce prejudices (Larzén-Östermark, 2011). Pre-service teachers adopted more critical perspectives towards their own countries (Cushner & Mahon, 2002; Medina-López-Portillo, 2004; Trilokekar & Kukar, 2011). Further development of intercultural competence also involved higher levels of identification with the host culture (Lee, 2009), adaptation to cultural differences (Anderson et al., 2006), risk-taking attitudes to try new cultural experiences (Jackson, 2008), and integration of new global identities (Jackson, 2008; Trilokekar & Kukar, 2011).

Among the limitations in pre-service teachers’ intercultural growth, Marx and Pray (2011) identified racist participant attitudes that contributed to feelings of vulnerability which in turn led to decreased communication with local Mexicans and a reinforcement of participants’ racist attitudes. Other constraints included persistent stereotyping (Jackson, 2008; Osler, 1998; Tusting, Crawshaw, & Callen, 2002), overestimation of participants’ intercultural competence (Jackson, 2008), a lack of awareness about power issues in socio-economic geopolitics (Osler, 1998), the feeling of being an outsider, and the difficulty of building new meanings (Trilokekar & Kukar, 2011).

Method

Context and Participants

This qualitative, descriptive case study (Merriam, 1988) involved 50 student teachers from two public Colombian universities. Twelve pre-service teachers, 24%, belonged to a university with a four-year English teaching program located in a principal city. Studying in a populous urban area might imply more access to various opportunities for travelling abroad. The remaining 38 students, 76%, studied at a regional five-year-degree-program, post-secondary institution in a modern languages (Spanish-English) program or in a foreign languages (English-French) program. In the latter setting, it is important to mention that pre-service teachers come mainly from small towns.

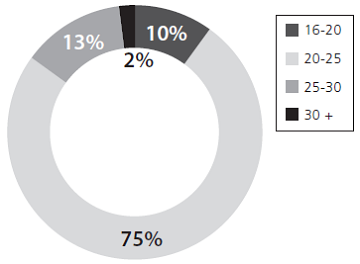

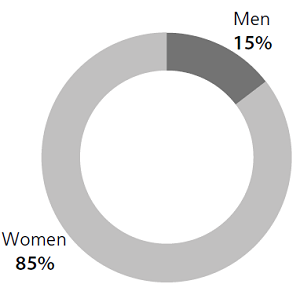

A total of 50 student teachers, nine males and 41 females from 20 to 30 years of age at the moment of their sojourn participated in the study (see Figures 1 and 2).

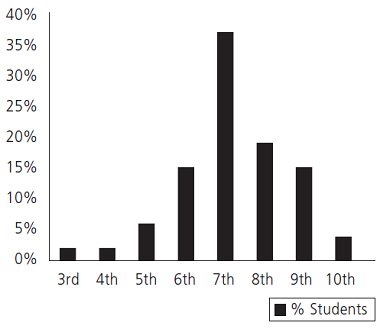

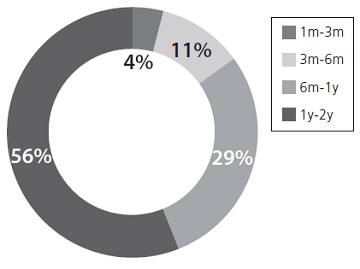

Most participants had never traveled abroad before. The majority travelled when they were in the seventh semester of their program, though some of them participated in earlier or more advanced stages of their studies (from fourth to tenth semesters). For most of them, the length of their experience varied from one to two years (see Figures 3 and 4). Neither of the two programs required student teachers to travel abroad to obtain their degree. These prospective EFL teachers took the initiative and made their own decisions and arrangements to enroll in travel abroad programs.

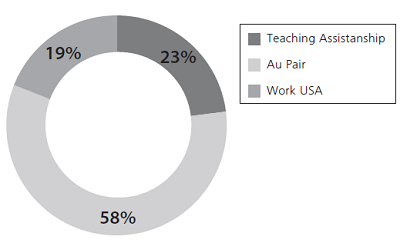

Travel Abroad Programs

Student-teachers enrolled in three different kinds of programs to travel to the US: Au Pair (29 students), Work Abroad (9 students), and Teaching Assistantship2 (12 students) (see Figure 5). Au Pair offers candidates the possibility of joining an American family through the daily care of its children and assures a rich cultural experience while being treated as another member of the host family. Requirements to join this program include: ages from 18 to 26 years old, a secondary education degree, some experience caring for children, a background check and proficiency in conversational English. Work Abroad touts their program as an opportunity to get acquainted with the American culture by working for different types of commercial enterprises such as summer camps, resorts, and theme parks. English improvement and adding international work experience to one’s resume are two of the advantages this program advertises. To enroll, applicants (ages 18 to 29) need sufficient proficiency in English and to be at an advanced stage in their university studies.

The third program, Teaching Assistantship, recruits overseas students to become elementary or high school teacher assistants. Furthermore, they might become “cultural ambassadors.” In order to enroll, applicants need to be from 21 to 29 years old, proficient in English, and pursuing a degree in education. This might be the only case in which student teachers’ experience abroad is connected, somehow, to their educational field.

Based on these programs’ web pages, and our participants’ voices, living a rich cultural experience is at the core of what the programs offer. However, “cultural experiences” are regarded as merely getting acquainted with food, festivals, and music, among others. Enjoying cultural involvement through living with native English speakers, taking courses, or working on their assignments are described as means for experiential learning on these web pages. These practices supposedly lead to the sojourner’s self-growth, moving from a level of mono-cultural awareness to a level of intercultural mediation.

Data Collection Instruments

Data are related to participants’ former work and residence abroad experiences in the US, from 2004 to 2011. Participants were contacted via e-mail by researchers in this study who clearly explained the aim of the research. Student teachers had attended classes guided by either one or the two researchers in the past, thus participants were acquainted with the researchers. An online survey (Appendix A) and a semi-structured interview (Appendix B) were used to collect data for this study from 2011 to 2012. The online survey was piloted and refined; 100 student teachers were contacted and 50 surveys were fully completed. This instrument explored student teachers’ personal backgrounds, expectations before the sojourn, and intercultural experiences.

Seven semi-structured interviews were conducted face to face and nine were developed using video calls in cases when both researchers and participants were in different geographical locations. These talks were audio recorded. Through this instrument, the researchers aimed at expanding participants’ responses in the surveys, as well as exploring in depth their multifaceted cultural experiences while living abroad.

Our interview protocol explored student teachers’ perceptions of their selection and preparation process, and problematic areas in the initial program stages. We also addressed participants’ interaction with Americans concentrating on their self-perception along with their attitudes towards the foreign culture during their time abroad. Finally, we considered the benefits and the challenges of the experiences.

Data Analysis and Findings

Principles from the grounded theory (Corbin & Strauss, 1998) provided guidelines used to classify data. Multiple readings of the information collected allowed us to determine the themes connected to our research objective. While we systematically compared, contrasted, and reduced data, we defined and labeled patterns. This supported us to build a comprehensive framework to answer our query. Methodological and researcher triangulation were used to assure reliability within the process (Janesick, 1994).

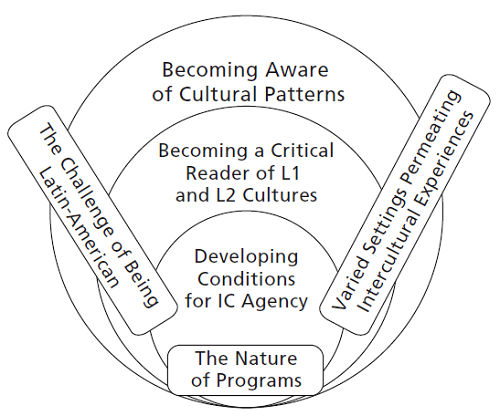

Figure 6 represents the overarching categories established to summarize and organize the data. We identified two main intertwined dimensions throughout participants’ international sojourn: the elements affecting intercultural development (represented by the rectangles) and the levels of inter-culturality participants revealed (represented by the circles).

The first dimension encompasses the nature of the program in which students engaged, the multifaceted settings where experiences occurred, and the perceived stereotyping participants felt subjected to because of their Latin-American origin. The second level, student teachers’ intercultural competence development emerged in the mist of the aforementioned influences. Participants gained awareness of cultural characteristics from their host and their native countries, attempted to take a critical stance of L1 and L2 cultures and seemed to start transiting from an ethnocentric to a more ethno-relative attitude. To begin with, the following pages describe the nuances of the factors shaping the experiences.

The Factors Affecting Pre-Service Teachers’ Intercultural Learning

The Nature of the Programs

Though participants were EFL pre-service teachers, they did not necessarily enroll in programs which were attuned to their academic backgrounds. As revealed above in Figure 5, only 23% (12 students) selected Teaching Assistantship, the program providing an experience in the teaching field. The remaining number of participants opted for Au Pair (29 students, 58%) and Working Abroad (9 students, 19%). Data show that the opportunities for interaction and formal or informal instruction leading to intercultural development were contingent upon the circumstances created by the programs in which the pre-service teachers participated. Fifteen student teachers in the Au Pair program, five in the Work Abroad program, and seven in the Teaching Assistantship program provided answers that guided us to establish this first factor. The following excerpt illustrates this influence:

I worked as a cashier in a restaurant. Then, interaction was not really varied. It mainly took place with the people I worked with. I only talked to clients when they paid their bills. (34, WA, Int)3

Though programs claimed participants would find a facilitating environment for cultural experiences, the opposite sometimes occurred as the previous testimony shows. Pre-service teachers adapted to conditions which were far from ideal and tried to access the learning opportunities that interaction with others would bring them. Consequently, these opportunities appeared as random events, rather than affairs organized, controlled, and monitored by the programs. Generally, in the Au Pair program, the approach families adopted in integrating participants, either as family members or as someone just providing a service, can be seen as a factor influencing participants’ opportunities for intercultural development which was akin to how the rules and dynamics of working assignments in Work Abroad and placement policies in Teaching Assistantship affected student teachers.

Varied Settings Permeating Intercultural Experiences

The concept of setting encompasses the influence that the places, the inhabitants of those places, and the circumstances characterizing those contexts exert on participants’ options to develop intercultural abilities. This finding parallels Medina-López-Portillo’s (2004) and Williams’ (2005) studies, which also found that direct contact with people and contexts influences intercultural learning. Based on our participants’ responses, we identified the kind of setting in connection with the social interactions that student teachers could experience and the multicultural nature of the US as salient topics to discuss in this section.

In general, student teachers were categorized according to the places where they lived and worked: 15 stayed in small rural areas (SRA), 15 in small urban areas (SUA), and 20 in large urban areas (LUA). Whereas students from the three groups reported they stayed in SUA, only student teachers enrolled in Au Pair and Work Abroad travelled to SRA and only participants in Au Pair and Teaching Assistantship stayed in LUA. Thus, while students in Au Pair were placed in any of the three settings, students in Work Abroad and Teaching Assistantship were placed in more specific contexts. In the case of the Work Abroad program, participants were mostly assigned to work at resorts located in small towns, and student teachers in the Teaching Assistantship program were mostly sent to a specific major city of the US and its suburbs.

While 42 participants found substantial opportunities for interaction within their host community or the place where they worked, a total of eight students did not. Among the latter group, six were female students in the Au Pair program, one was a male student in the Teaching Assistantship program (both of them long-term programs), and one was a male student in the Work Abroad program (a short-term program). In addition, four of these participants were in SRAs, two in SUAs, and two in LUAs.

Though in general participants’ agency affected their opportunities for interaction with others, their settings facilitated or constrained their opportunities for intercultural knowledge and skills construction:

Well, all the time I shared experiences with people from other cultures. The group I remembered the most was at the university with Arabs, yes, Arabs, Muslins. I practiced their rituals with them and so I learned a lot…I realized they were equal to us, and just have a different point of view. (24, AU, Int)

The participant above talks about university courses she attended. This setting gathered people from different countries and cultures which precipitated multicultural contacts. The student teacher’s willingness and initiative to experience her peers’ cultural rituals become fundamental for intercultural learning. The multicultural nature of the US was highlighted by 15 student teachers in the Au Pair, three in the Work Abroad and two in the Teaching Assistantship programs. Overall, participants claimed they were positively affected by multiculturalism since their stereotypes were often challenged and they formed a more accurate view of individuals from those other countries.

The Challenge of Being Latin-American

This theme focuses on the images that individuals from the US and Colombia hold of each other when they interact. Our study informs us of how these stereotypes shaped participants’ intercultural attitudes. For 10 student teachers, seven in the Au Pair, two in the Work Abroad and one in the Teaching Assistantship programs, their encounters with people in the US became negative experiences when they felt discouraged to communicate due to stereotypes about Latin-Americans. The composition of this group reveals that all of them except one were women and most of them (7) were in a long-term stay in the host country. In contrast, two participants in the Teaching Assistantship program, one of them a man and the other a woman, mentioned that they did not suffer or notice any kind of discrimination because of their being Colombians.

The 10 students who reported stereotyping expressed that the image of Colombia was reduced to drug dealing, poverty, violence, and underdevelopment. This type of stereotyping and its effects has been documented by Marx and Pray (2011). Their findings suggest how stereotypes, which US student teachers took with them, led them to include Mexicans within a general negative Latin-American profile, constraining the student teacher’s interaction opportunities.

The evidence below supports our results:

Every time American people asked me about my origin and I answered I was from Colombia the first thing they mentioned was drugs. Initially that bothered me, but I learnt not to react every time because they would continue picking on me. (45, AU, S)

The attitude of the previous student demonstrates how she faced negative stereotyping which initially had a negative impact, but subsequently led to the development of a mitigation strategy used in future encounters.

Moreover, as Marx and Pray (2011) found, the effects of this stereotyping on our participants encouraged the reinforcement of prejudices against the US culture:

For people in the US we are not Colombian, Mexican, Bolivian people, we are Latin-American, but we are not the same. The majority of them (US people) care about themselves; they do not realize what happens around the world. (8, AU, S)

The previous participant reacted to the idea of Latin-Americans comprising a single undifferentiated cultural group, a belief many US citizen exhibit, by responding with her own stereotype of Americans as egocentric and ignorant. On the positive side, this prejudice about Latin-Americans seems to broaden the participant’s awareness of her national culture. In addition to the aforementioned factors, our findings describe the nuances of participants’ apparent gains in their intercultural attitudes, abilities, and knowledge at different levels.

Student Teachers’ Intercultural Learning

Becoming Aware of Cultural Patterns

Participants’ awareness of both Colombian and US cultural patterns evidenced an embryonic development of intercultural competence. This stage was embryonic in the sense that in their international sojourn student teachers started to identify cultural differences between their own culture and the host country. Data collected showed that 29 (58%) of the participants became aware of cultural patterns. Specifically, the numbers above correspond to five (55%) of the students in the Work Abroad program, eight (66%) in the Teaching Assistantship program and 16 (55%) in the Au Pair program. As can be seen, this pattern appeared in students who participated in the three programs. Consequently, short or long stays abroad can generate participants’ cultural awareness.

Cultural awareness seems to constitute the first phase of ethno-relativism, “acceptance,” conceptualized by M. J. Bennett (1993). It implies that differences at the cultural level are acknowledged but not judged in regard to individuals’ behaviors and the actual state of affairs around them. Framing this initial stage of our findings within Byram’s (1997, p. 34) model, we can argue that our participants demonstrated “knowledge of self and others,” allowing them to discern cultural patterns and to interact accordingly.

As an instance of cultural awareness, we would like to remark that 10 student teachers’ comments acknowledged the cultural richness of Colombia, the need to value positive aspects in Colombia, and the importance of gaining understanding regarding what Colombian society might focus on in order to improve living conditions. This idea can be evidenced in the following excerpt.

Then I started analyzing my life in Colombia and I was aware about how brave many people are when they fight for their dreams and needs. Sometimes while being in Colombia we criticized how violent, contaminated, and poor (mentally and physically) we can be. But being away one realizes how valuable it is to be in Colombia…Your culture comes to gain a higher appreciation. (49, AU, S)

As for the participants’ consciousness of American cultural patterns, it was evident that the US was conceived as a multicultural country, so that generalizing the way an American would act was difficult. Similarly, participants perceived certain behavioral patterns and attitudes that might represent cultural features:

For example, the way you greet is a little bit different and it varies from person to person. We are more polite and they (US people) are less affectionate; they were not so close to their children. (2, TA, Int)

Inasmuch as Colombian student teachers in their US sojourn identified and respected cultural divergences showing tolerance, our findings aligned with studies conducted by Lee (2009), Medina-López- Portillo (2004), and Osler (1998).

Becoming a Critical Reader of L1 and L2 Cultures

Some participants moved a step forward from awareness of cultural differences to taking a critical stand concerning both cultures. On the whole, 36 (72%) student teachers voiced their critical interpretations of the L1 and L2 cultures. Seven of these participants were in the Work Abroad program (78%), nine in the Teaching Assistantship program (66%) and 20 in the Au Pair program (69%). These percentages show that participants in all three types of programs, regardless of how long they stayed, exhibited critical readings of L1 and L2 cultures.

Our conception of a critical reader of culture aligns with Byram’s (1997) postulates regarding the interpretation of cultural manifestations and the interconnections that individuals are able to establish between cultures. People’s existing knowledge propels their ability to interpret cultural meanings.

By virtue of the intercultural experience student teachers lived, favorable patterns of the American culture were identified; among them the high environmental consciousness, social organization, and respect. In addition, participants highlighted positive attitudes such as hard work, patience, and respect as well as the value American people give to listening:

There (US) organization and effort make things work better. Attitudes such as respecting copyright, making pedestrians a priority, and recycling become reasons why a country might be perceived differently. (1, TA, S)

On the other hand, egocentric attitudes, showing distant social relationships and being less affectionate were characteristics some participants in this study perceived as common in the American culture. These perceptions are connected to one’s views of the way people interrelate in the home country.

Becoming acute readers of the realities that surrounded them opened the possibility for the participants to challenge stereotypes about the American culture. Owing to this, student teachers developed more understanding and empathic attitudes towards the cultural differences between the home and host countries. Such growth in their intercultural competence is evident in the excerpt below:

When I was in Colombia my perception of people from other countries was solely based on what books showed me especially prototypes. For example, for me American were cold, strategic, junk-food eaters, and greedy, but, when I arrived to the US I realized they were not like that, not all of them were robots. (48, AU, S)

Similar to participants in studies conducted by Cushner and Mahon (2002), and Larzén-Östermark (2011), the previous student’s examination of her perceptions about American culture seemed to allow her to build a more nuanced and realistic view of US people.

In addition to assuming a critical stance towards the L2 culture, there were instances in which they provided analytical perspectives regarding their home culture:

I had always been quite timid; I was not open enough to talk to people. Once I arrived to the US and I met people from Colombia who told me that people from my region were shy, I started to notice it, and it’s true. We are unsociable, no, no unsociable, timid, introverted. (45, TA, Int)

Participants’ critical reading of their own culture has also emerged in studies by Cushner and Mahon (2002), Medina-López-Portillo (2004), and Trilokekar and Kukar (2011).

Developing Conditions for Cultural Agency

Student teachers’ responses led us to identify another characteristic in their intercultural growth. Six (66%) student teachers in the Work Abroad program, seven (58%) in the Teaching Assistantship program and 20 (68%) in the Au Pair program expressed that the international sojourn had modified both their attitudes and personality traits. This shows that participants in the three programs, whether in short or long stays abroad, were individually influenced by their experiences.

Regarding the first level of transformation, we established five spheres to group the qualities student teachers reported they had adopted as a consequence of their experience. The most common quality referred to tolerance and involved other traits such as flexibility, patience, respect, open-mindedness, and understanding to avoid light judgment of others. The second in frequency was the adoption of assertive attitudes in connection to building a stronger character and being more mature. A third trait was students’ becoming self-sufficient and independent. The fourth trait gravitated towards self-confidence in connection with extroversion and spontaneity leading to risk-taking. Discipline, responsibility, and organization comprise the last sphere. The following excerpt provides some evidence supporting this finding,

I also adapted to superabundance of resources. For them it is easier than for us to throw to the garbage things they have not even used as food, paper, or technological resources…Now I am more tolerant and open in regards to differences with other people. I value more my own culture and the efforts we make to develop our activities. I am more resourceful and I know better about how to treat foreigners who live in Colombia. (7, WA, S)

A reduced number of participants’ answers evidenced the remaining stage of intercultural competence identified within what we have called cultural agency. Fourteen (28%) students in the three programs: Four (45%) students in the Work Abroad program and two (17%) in the Teaching Assistantship program explained they had taken actions to transform aspects in their lives due to their experience abroad. Similarly, eight (29%) participants in the Au Pair program claimed they experienced changes. From those eight students in the Au Pair program, four were the only ones, considering the three programs, who claimed they had tried to produce a change in other people’s ethnocentric views.

Our understanding of the emergence of transformative actions within the experience concurs with Buttjes and Byram’s (1991) reference to “the transcultural level: . . . the learner is able to evaluate intercultural differences and to solve intercultural problems” (p. 143). The aforementioned statement implied acknowledging and understanding differences as a starting point to take action and change as cultural beings. Likewise, a few individuals look for diverse strategies to make such change permeate the perceptions that the foreign country communities hold regarding, in this case, the Colombian culture. This level of understanding is revealed in the evidence below.

Talking about stereotypes, the American family I lived with believed Colombia was a poor, underdeveloped country where people were usually armed and selling drugs. Though trying to change people’s mind is difficult, I showed them that, despite Colombia has some problems, these are not different from the social and political difficulties USA faces. (29, AU, S)

In addition to revealing how this participant’s identity might have started to be reshaped, this excerpt also attests to what M. J. Bennett (1993) defines as “adaptation” in regard to ethno-relativism. The student teacher’s adaptation moves from a cognitive to a behavioral level, but it also can include the affective realm. Adaptation as a result of international sojourns has also been documented by Anderson et al. (2006) in the context of short-term visits to an English speaking country.

Modifications might have also occurred in participants’ lifestyles. Some of them consider that their transformations, which started in the US, continued even when they returned to Colombia:

That was another habit that started to grow when I was there, I started reading more books, to set aims about how many books I would read, so I started to cultivate this aspect about reading there. (6, TA, Int)

Though, as illustrated above, several student teachers might have progressed towards higher stages of intercultural competence, more complex stages as the ones reported in Cushner and Mahon (2002), Jackson (2008), and Sharma et al. (2011) were not identified. Whereas these researchers’ participants developed metacognitive skills such as their acknowledgment of the importance of their intercultural processes and their consciousness of the function that their critical reflection had in their progress, Colombian pre-service teachers’ reports did not account for this type of metacognition.

Conclusions and Pedagogical Implications

This paper reports on how the experience of EFL Colombian student teachers working and living in the US is related to their development of intercultural competence. In brief, the nature of the programs framed participants’ opportunities for intercultural learning. Working became the main agenda in these programs, superseding student teachers’ expectations of formal academic learning and oftentimes constraining the likelihood of informal interaction. In only one type of program, Teacher Assistantship, did working assignments involve participants’ field of expertise.

The US’s multi-culturality offers student teachers fertile terrain in which to establish relationships that lead to increased intercultural knowledge. However, the kinds of settings and the opportunities for interaction within those settings bolstered or hindered participants’ development. In addition, while the negative stereotyping of Latin-Americans constituted a psychological factor which inhibited some participants in their efforts to connect with the host culture and sometimes fed prejudices towards the US, these stereotypes also influenced participants’ reaffirmation of their national identity.

Student teachers’ testimonies evidenced gains achieved through three stages: At the first level, they disclosed intercultural awareness as they were able to identify cultural differences between their own and the host country cultures. In a second stage, individuals developed a more nuanced view of both cultures through the analysis of positive and negative aspects of the two countries. Similar percentages of students in the short-term and the two long-term programs evidence “cultural awareness.” Regarding “the critical reading of culture,” there were also approximate percentages between short- and longterm programs.

A third stage of IC development addressed student teachers’ understanding of cultural differences as a starting point to take action and change as cultural beings. The percentages of students exhibiting “cultural awareness” and a “critical reading of culture,” in contrast to those who reported adopting specific actions, were substantially higher in all the three programs. Metacognitive skills, which also imply higher stages of IC development, were not evidenced in our participants’ responses.

The private and commercial nature of companies for traveling and working abroad in this study substantially problematizes what should be the real nature of traveling, working, and studying abroad for student teachers. Bearing the previous issue in mind and considering that universities cannot stop student teachers from enrolling in these programs if they so wish, universities most suitable course of action should be to propose alternatives.

The conclusions reported so far suggest the need for university administrators to align with teachers and students in order to plan and design traveling abroad programs whose nature reflects EFL student teachers’ professional field. This population’s learning throughout their international sojourns should not mainly be the product of their individual agency and fortuitous circumstances. It is evident that the decisions which make a substantial difference in participants’ experiences, for example, the assignment location and undergraduate program trajectories, require deeper and more informed considerations.

Taking advantage of Colombian universities’ offices to facilitate international cooperation, university officials can work on establishing strategic alliances to learn from the experience of higher education institutions located overseas. Of special interest should be institutions with substantial trajectories in programs which clearly value the “study” abroad experience as much as or more than the working abroad experience. Establishing cooperation can begin by arranging conferences and visits, not only to learn about those other university programs, but to negotiate the establishment of bilateral study abroad programs.

Teams composed of university officials, teachers who have studied abroad in countries where languages of interest are spoken, and student teachers previously involved in these international sojourns can work together. They can generate and monitor the implementation of plans to evaluate traveling abroad experiences. Subsequently, the product of this evaluation can be configured into plans to design new programs which are informed by the myriad factors affecting particular populations of students.

Based on this study, an initial issue regarding the planning of new programs can be to aim not only at participants’ development of “cultural awareness” and “critical interpretation” of L1 and L2 cultures, but also to target students’ cultural agency and metacognition. Considering documented experiences, the adoption of pre-, during, and post stages in participants’ preparation for study abroad resonates as a robust alternative to advance their intercultural abilities.

Integrating structured and sequential academic preparation into the study abroad experience would probably require reshaping curricular elements. University teachers become the most relevant leaders to conduct this task. To begin with, a pre-sojourn course, proposing a critical approach to looking at culture in contrast to the traditional encyclopedic perspective becomes a helpful alternative. In order to achieve this goal, student teachers can, for instance, take part in tele-collaboration to establish contact with people and cultural artifacts in their countries of interest. These experiential activities can be shaped and informed by theoretical constructs and research in the area of intercultural competence. Awareness of cases found in studies by means of individual and group tools like journals and discussions, can equip participants with strategies to better manage issues as stereotyping, cultural differences, and shock, among others.

Student teachers’ conclusions from their participation in the pre-sojourn course can become the starting point for them to involve metacognitive skills. This might be possible if they set their own learning goals before enrolling in the experience and employ specific tasks to monitor those objectives while they travel. Thus, participants can make self-directed contributions to their intercultural learning benefitting from a well-informed and coherent program. Finally, they can gain from a post-sojourn phase in which they look retrospectively at their process in order to explore the effects of their international experience at the emotional, psychological, and professional levels.

1In this study, we characterize study abroad programs as short or long-term based on our adaptation of Engle and Engle’s (2003) classification. Accordingly, we will call a program from three to 23 weeks a short-term program. A long-term program lasts six months or more. This means that the programs lasting more than one year will be part of the latter category.

2The original names of these programs were not included. They have been changed, but the names we selected reflect their general nature.

3Through this manuscript, numbers identify the participants; the abbreviations following the numbers refer to the program participants enrolled in: Au Pair (AU), Working Abroad (WA), and Teacher Assistantship (TA). Regarding data collection instruments, Int stands for interview and S for surveys. Participants’ original testimonies in Spanish have been translated into English by the researchers keeping faithful to the original ideas.

References

Anderson, P., Lawton, L., Rexeisen, R. J., & Hubbard, A. C. (2006). Short-term study abroad and intercultural sensitivity: A pilot study. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30(4), 457-469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.10.004.

Bennett, J. M. (2008). Transformative training: Designing programs for culture learning. In M. A. Moodian (Ed.), Contemporary leadership and intercultural competence: Exploring the cross-cultural dynamics within organizations (pp. 95-110). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bennett, M. J. (1993). Towards ethnorelativism: A developmental model of intercultural sensitivity. In R. M. Paige (Ed.), Education for the intercultural experience (pp. 21-71). Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press.

Buttjes, D., & Byram, M. (1991). Mediating languages and cultures: Towards intercultural theory of foreign language education. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Camilleri, A. G. (2002). How strange! The use of anecdotes in the development of intercultural competence. Strasbourg, FR: Council of Europe.

Coleman, J. A. (1997). Residence abroad within language study. Language Teaching, 30(1), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444800012659.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cushner, K., & Karim, A. U. (2004). Study abroad at the university level. In D. Landis, J. M. Bennett, & M. J. Bennett (Eds.), Handbook of intercultural training (pp. 289-309). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452231129.n12.

Cushner, K., & Mahon, J. (2002). Overseas student teaching: Affecting personal, professional, and global competencies in an age of globalization. Journal of Studies in International Education, 6(1), 44-58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315302006001004.

Deardorff, D. K. (2008). Intercultural competence: A definition, model and implications for education abroad. In V. Savicki (Ed.), Developing intercultural competence and transformation: Theory, research, and application in international education (pp. 32-52). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Engle, L., & Engle, J. (2003). Study abroad levels: Toward a classification of program types. Frontiers: The interdisciplinary journal of study abroad, 9(1), 1-20.

Fantini, A. E. (2009). Assessing intercultural competence. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 456-476). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Jackson, J. (2008). Globalization, internationalization, and short-term stays abroad. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 32(4), 349-358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2008.04.004.

Janesick, V. J. (1994). The dance of qualitative research design. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 209-219). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Larzén-Östermark, E. (2011). Intercultural sojourns as educational experiences: A narrative study of the outcomes of Finnish student teachers’ language-practice periods in Britain. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 55(5), 455-473. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2010.537687.

Lee, J. F. (2009). ESL student teachers’ perceptions of a short-term overseas immersion programme. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(8), 1095-1104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.03.004.

Marx, S., & Pray, L. (2011). Living and learning in Mexico: Developing empathy for English language learners through study abroad. Race Ethnicity and Education, 14(4), 507-535. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2011.558894.

Medina-López-Portillo, A. (2004). Intercultural learning assessment: The link between program duration and the development of intercultural sensitivity. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad, 10(1), 179-199.

Merriam, S. B. (1988). Case study research in education: A qualitative approach. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Osler, A. (1998). European citizenship and study abroad: Student teachers’ experiences and identities. Cambridge Journal of Education, 28(1), 77-96. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764980280107.

Pence, H. M., & Macgillivray, I. K. (2008). The impact of an international field experience on preservice teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(1), 14-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2007.01.003.

Petras, J. (2000). Overseas education: Dispelling official myths in Latin America. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad, 6(1), 73-81.

Pray, L., & Marx, S. (2010). ESL teacher education abroad and at home: A cautionary tale. The Teacher Educator, 45(3), 216-229. https://doi.org/10.1080/08878730.2010.488099.

Santamaría, L. J., Santamaría, C. C., & Fletcher, T. V. (2009). Journeys in cultural competency: Pre-service US teachers in Mexico study-abroad programs. Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education, 3(1), 32-51. https://doi.org/10.1080/15595690802584166.

Sharma, S., Aglazor, G. N., Malewski, E., & Phillion, J. (2011). Preparing global minded teachers for US American classrooms through international cross-cultural field experiences. Delhi Business Review, 12(2), 33-44.

Trilokekar, R. D., & Kukar, P. (2011). Disorienting experiences during study abroad: Reflections of preservice teacher candidates. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(7), 1141-1150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.06.002.

Tusting, K., Crawshaw, R., & Callen, B. (2002). ‘I know, ‘cos I was there’: How residence abroad students use personal experience to legitimate cultural generalizations. Discourse & Society, 13(5), 651-672. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926502013005278.

Williams, T. R. (2005). Exploring the impact of study abroad on students’ intercultural communication skills: Adaptability and sensitivity. Journal of Studies in International Education, 9(4), 356-371. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315305277681.

About the Authors

John Jairo Viafara González holds a BEd in Philology and Languages, English, from Universidad Nacional de Colombia and an MA in Applied Linguistics to TEFL from Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas (Colombia). He is currently a PhD candidate in Second Language Acquisition and Teaching from the University of Arizona. He is a main researcher of the RETELE research group indexed in Colciencias.

J. Aleida Ariza Ariza holds a BEd in Philology and Languages, English-Spanish from Universidad Nacional de Colombia, and an MA in Applied Linguistics to TEFL from Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas (Colombia). Currently she is an assistant professor at Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia. She is also a main researcher of the RETELE research group indexed in Colciencias.

Appendix A: Online Survey*

*Data collection instruments in Appendix A and B were originally administered and conducted in Spanish. They have been translated into English by the authors of this manuscript to match the language in the main body of the document.

Dear participant, the aim of this survey is to explore your perceptions in regard to your experience while living or studying abroad. Please read and answer carefully each one of the following questions. Fill in a survey for each experience you had abroad. We appreciate your participation in this study.

Background Information

1. What was your age range when you when you travelled?

☐ 16 to 20

☐ 20 to 25

☐ 20 to 25

☐ Over 30

2. Write the year when you started and when you finished your experience abroad.

3. Write the number of the last academic semester you enrolled in before your trip.

4. Select the travel abroad program in which you participated.

☐ Au Pair

☐ Teaching Assistantship

☐ Work USA

☐ Other

Which?

5. How long were you part of that program?

☐ 1 to 3 months

☐ 3 to 6 months

☐ 6 months to 1 year

☐ 1 to 2 years

☐ More than 2 years

6. Write about the city/town where you lived. Describe the place and the people there (number of inhabitants, origin, other characteristics, urban or rural context?).

7. How do you think that your interaction with the people in this community might have contributed to the purpose of your trip?

8. Did the program in which you participated offer you any preparation for the experience?

☐ Yes

☐ No

9. If you chose a positive answer for the previous question, describe how that preparation was.

Interculturality

10. Do you think that the way you perceived yourself and others—talking about the context where your

experience abroad took place—changed because of the experiences you underwent there? Explain.

☐ Yes

☐ No

11. To what extent do you consider that this experience affected your comprehension of the values, beliefs, and attitudes of the people who lived in the country where you stayed? Describe specific situations you might have experienced.

12. Have you noticed any changes in the way you act in connection with your experience abroad? Explain your answer.

Suggestions

Question Number 7 in this survey explores the previous preparation you might have undertaken before the trip. After your experience, what do you think the preparation should include?

As one of the means for data collection, this study includes an interview. If you decided to participate

in the interview, which of the following options would be the most suitable for you?

☐ Face to face

☐ Skype

☐ Messenger

Other, Which?

Appendix B: Semi-Structured Interview Protocol

- In regard to the traveling abroad program, what would you change starting from the selection, then preparation process, and after that the other stages of the experience?

- How would you describe your interaction with the people you met during your experience abroad?

- Did this experience change the perception you had of yourself? Yes or No? Explain “how”.

- Did your perception of the US culture change because of the trip? Yes or No? Explain “how”.

- How do you think your expectations of becoming a foreign language teacher might have changed as a consequence

of your experience abroad?

In your survey, you reported you gained in _____________. Why do you think this occurred?

References

Anderson, P., Lawton, L., Rexeisen, R. J., & Hubbard, A. C. (2006). Short-term study abroad and intercultural sensitivity: A pilot study. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30(4), 457-469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.10.004.

Bennett, J. M. (2008). Transformative training: Designing programs for culture learning. In M. A. Moodian (Ed.), Contemporary leadership and intercultural competence: Exploring the cross-cultural dynamics within organizations (pp. 95-110). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bennett, M. J. (1993). Towards ethnorelativism: A developmental model of intercultural sensitivity. In R. M. Paige (Ed.), Education for the intercultural experience (pp. 21-71). Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press.

Buttjes, D., & Byram, M. (1991). Mediating languages and cultures: Towards intercultural theory of foreign language education. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Camilleri, A. G. (2002). How strange! The use of anecdotes in the development of intercultural competence. Strasbourg, FR: Council of Europe.

Coleman, J. A. (1997). Residence abroad within language study. Language Teaching, 30(1), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444800012659.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cushner, K., & Karim, A. U. (2004). Study abroad at the university level. In D. Landis, J. M. Bennett, & M. J. Bennett (Eds.), Handbook of intercultural training (pp. 289-309). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452231129.n12.

Cushner, K., & Mahon, J. (2002). Overseas student teaching: Affecting personal, professional, and global competencies in an age of globalization. Journal of Studies in International Education, 6(1), 44-58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315302006001004.

Deardorff, D. K. (2008). Intercultural competence: A definition, model and implications for education abroad. In V. Savicki (Ed.), Developing intercultural competence and transformation: Theory, research, and application in international education (pp. 32-52). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Engle, L., & Engle, J. (2003). Study abroad levels: Toward a classification of program types. Frontiers: The interdisciplinary journal of study abroad, 9(1), 1-20.

Fantini, A. E. (2009). Assessing intercultural competence. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 456-476). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Jackson, J. (2008). Globalization, internationalization, and short-term stays abroad. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 32(4), 349-358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2008.04.004.

Janesick, V. J. (1994). The dance of qualitative research design. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 209-219). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Larzén-Östermark, E. (2011). Intercultural sojourns as educational experiences: A narrative study of the outcomes of Finnish student teachers’ language-practice periods in Britain. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 55(5), 455-473. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2010.537687.

Lee, J. F. (2009). ESL student teachers’ perceptions of a short-term overseas immersion programme. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(8), 1095-1104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.03.004.

Marx, S., & Pray, L. (2011). Living and learning in Mexico: Developing empathy for English language learners through study abroad. Race Ethnicity and Education, 14(4), 507-535. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2011.558894.

Medina-López-Portillo, A. (2004). Intercultural learning assessment: The link between program duration and the development of intercultural sensitivity. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad, 10(1), 179-199.

Merriam, S. B. (1988). Case study research in education: A qualitative approach. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Osler, A. (1998). European citizenship and study abroad: Student teachers’ experiences and identities. Cambridge Journal of Education, 28(1), 77-96. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764980280107.

Pence, H. M., & Macgillivray, I. K. (2008). The impact of an international field experience on preservice teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(1), 14-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2007.01.003.

Petras, J. (2000). Overseas education: Dispelling official myths in Latin America. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad, 6(1), 73-81.

Pray, L., & Marx, S. (2010). ESL teacher education abroad and at home: A cautionary tale. The Teacher Educator, 45(3), 216-229. https://doi.org/10.1080/08878730.2010.488099.

Santamaría, L. J., Santamaría, C. C., & Fletcher, T. V. (2009). Journeys in cultural competency: Pre-service US teachers in Mexico study-abroad programs. Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education, 3(1), 32-51. https://doi.org/10.1080/15595690802584166.

Sharma, S., Aglazor, G. N., Malewski, E., & Phillion, J. (2011). Preparing global minded teachers for US American classrooms through international cross-cultural field experiences. Delhi Business Review, 12(2), 33-44.

Trilokekar, R. D., & Kukar, P. (2011). Disorienting experiences during study abroad: Reflections of preservice teacher candidates. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(7), 1141-1150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.06.002.

Tusting, K., Crawshaw, R., & Callen, B. (2002). ‘I know, ‘cos I was there’: How residence abroad students use personal experience to legitimate cultural generalizations. Discourse & Society, 13(5), 651-672. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926502013005278.

Williams, T. R. (2005). Exploring the impact of study abroad on students’ intercultural communication skills: Adaptability and sensitivity. Journal of Studies in International Education, 9(4), 356-371. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315305277681.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Alexánder Ramírez-Espinosa. (2023). Culture-Related Issues in Teacher Education Programs: The Last Decade in Colombia. HOW, 30(1), p.144. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.30.1.730.

2. Kelsey Inouye, Soyoung Lee, Yusuf Ikbal Oldac. (2023). A systematic review of student agency in international higher education. Higher Education, 86(4), p.891. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00952-3.

3. Christo Joseph. (2022). New Approaches to CSR, Sustainability and Accountability, Volume III. Accounting, Finance, Sustainability, Governance & Fraud: Theory and Application. , p.169. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-9364-9_11.

4. Joanna Pfingsthorn, Anna Czura. (2017). Student teachers’ intrinsic motivation during a short-term teacher training course abroad. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 30(2), p.107. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2016.1251942.

5. Vida Dehnad. (2019). Sustainable Transdisciplinary Future for English Majors in Iran by Implementing a New Paradigm. Interchange, 50(1), p.77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10780-018-9342-5.

6. Denise Davis-Maye, Annice Yarber-Allen, Tamara Bertrand Jones. (2016). Handbook of Research on Efficacy and Implementation of Study Abroad Programs for P-12 Teachers. Advances in Higher Education and Professional Development. , p.400. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-1057-4.ch022.

7. Angela Yicely Castro-Gárces. (2022). Knowledge-Base in ELT Education: A Narrative-Driven Discussion. HOW, 29(1), p.194. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.29.1.608.

8. Yamith Joss Fandiio Parra. (2017). Formaciin Y Desarrollo Docente En Lenguas Extranjeras: Revisiin Documental De Modelos, Perspectivas Y Pollticas (Teacher Training and Development in Foreign Languages: Documentary Review of Models, Perspectives and Policies). SSRN Electronic Journal, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2981869.

9. Andrés Mauricio Potes-Morales. (2024). Critical Interculturality and CALL in ELT: A Necessary Approach in Colombian Contemporary Education. Praxis, Educación y Pedagogía, (10), p.e40412298. https://doi.org/10.25100/praxis_educacion.v0i10.12298.

10. Martha García Chamorro, Monica Rolong Gamboa, Nayibe Rosado Mendinueta. (2022). Initial Language Teacher Education: Components Identified in Research. Journal of Language and Education, 8(1), p.231. https://doi.org/10.17323/jle.2022.12466.

11. M. Martha Lengeling, Melanie L. Schneider. (2023). A Preservice Teacher’s Experiences Teaching English Abroad: From ESL to EFL. Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 25(2), p.81. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v25n2.101608.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.