The Cultural Content in EFL Textbooks and What Teachers Need to Do About It

El contenido cultural en los textos de inglés y qué necesitan hacer los profesores al respecto

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v17n2.44272Keywords:

Communicative textbooks, deep culture, EFL learners, intercultural communicative competence, surface culture (en)Competencia comunicativa intercultural, estudiantes de inglés, cultura profunda, cultura superficial, textos comunicativos (es)

This article analyzes the cultural content in three communicative English as a foreign language textbooks that are used as main instructional resources in the English classroom. The study examined whether the textbooks include elements of surface or deep culture, and the findings indicate that the textbooks contain only static and congratulatory topics of surface culture and omit complex and transformative forms of culture. Consequently, the second part of the article suggests how teachers can address deep-rooted aspects of culture that might help English as a foreign language learners build more substantive intercultural competence in the language classroom.

En este artículo se analiza el contenido cultural en tres textos de inglés comunicativo utilizados como el principal recurso de enseñanza en la clase de inglés. Se indagó si los textos incluyen elementos de la cultura superficial o de la cultura profunda. Se observó que los textos sólo presentan temas “admirables” y representativos de la cultura superficial y no ofrecen temas complejos y trasformativos de la cultura profunda. En consecuencia, en la segunda parte del artículo se sugiere a los profesores de inglés cómo abordar aspectos complejos de la cultura profunda que podrían ayudarle a los estudiantes de inglés como lengua extranjera a construir una competencia intercultural más sólida.

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v17n2.44272

The Cultural Content in EFL Textbooks and What Teachers Need to Do About It

El contenido cultural en los textos de inglés y qué necesitan hacer los profesores al respecto

Luis Fernando Gómez Rodríguez*

Universidad Pedagógica Nacional, Bogotá, Colombia

This article was received on July 3, 2014, and accepted on February 2, 2015.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Gómez Rodríguez, L. F. (2015). The cultural content in EFL textbooks and what teachers need to do about it. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 17(2), 167-187. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v17n2.44272.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This article analyzes the cultural content in three communicative English as a foreign language textbooks that are used as main instructional resources in the English classroom. The study examined whether the textbooks include elements of surface or deep culture, and the findings indicate that the textbooks contain only static and congratulatory topics of surface culture and omit complex and transformative forms of culture. Consequently, the second part of the article suggests how teachers can address deep-rooted aspects of culture that might help English as a foreign language learners build more substantive intercultural competence in the language classroom.

Key words: Communicative textbooks, deep culture, EFL learners, intercultural communicative competence, surface culture.

En este artículo se analiza el contenido cultural en tres textos de inglés comunicativo utilizados como el principal recurso de enseñanza en la clase de inglés. Se indagó si los textos incluyen elementos de la cultura superficial o de la cultura profunda. Se observó que los textos sólo presentan temas “admirables” y representativos de la cultura superficial y no ofrecen temas complejos y trasformativos de la cultura profunda. En consecuencia, en la segunda parte del artículo se sugiere a los profesores de inglés cómo abordar aspectos complejos de la cultura profunda que podrían ayudarle a los estudiantes de inglés como lengua extranjera a construir una competencia intercultural más sólida.

Palabras clave: competencia comunicativa intercultural, estudiantes de inglés, cultura profunda, cultura superficial, textos comunicativos.

Introduction

Communicative textbooks occupy a main place in teaching English as a foreign language (EFL) because many teachers depend on them as the bases for helping learners develop communicative competence: the ability to use language, convey messages, and negotiate meaning with other speakers in social contexts of real life (Bachman, 1999; Savignon, 1997, 2001). To accomplish this task, textbooks include lists of communicative functions, grammar forms, and language skills to be practiced. Additionally, they display communicative tasks that simulate or are genuine real-life situations. However, little attention has been given to considering whether textbooks incorporate sufficient material to help learners build intercultural communicative competence (ICC). Tudor (2001) indicates that the sociocultural dimensions of communication and the cultural contents intervene significantly in language use and that, therefore, culture cannot be ignored in program designs and teaching. In this sense, culture cannot be disregarded in the design of communicative textbooks.

Currently, the necessity to learn a foreign language goes far beyond learning grammar forms veiled in communicative functions. In consequence, the EFL field cannot ignore that learners must develop intercultural awareness to fit into a globalized world in which people from different cultural backgrounds establish international relations and become intercultural speakers (Banks, 2004; Byram, 1997). Learners need to foster what Kumaravadivelu (2008) has called global cultural consciousness, through which students learn to interact appropriately with new cultures that are often very different from their own. Then, if in many education settings the English language is taught through communicative textbooks, it is expected that they will provide the means to address the foreign culture. With this goal, textbooks should promote the enhancement of ICC, which is defined as the ability to understand and interact with people of multiple social identities and with their own individuality (Byram, Gribkova, & Starkey, 2002).

In light of the previous assertions, this article analyzes the cultural content presented in three EFL communicative textbooks that are known worldwide. The analysis explores whether these textbooks offer rich content about the target/foreign culture/s and to what extent they might prepare learners to become not only communicatively competent but also intercultural beings. The analysis was supported by theoretical views related to the distinction between surface culture and deep culture, which are explained below.

Theoretical Views on Culture

Culture Involves Deep Culture, Not Only Surface Culture

The EFL field has generally focused on teaching elements of surface culture, that is, the easily observable (Hinkel, 2001) and static elements that represent a nation. EFL materials often include holidays, tourist sites, famous people’s achievements, and food. However, these surface forms of culture are not sufficient for students to understand the target culture because they only entail the accumulation of general fixed information and do not provide opportunities to address the underlying sociocultural interactions that occur in different backgrounds.

In contrast, deep culture embraces invisible meanings associated with a region, a group of people, or subcultures that reflect their own particular sociocultural norms, lifestyles, beliefs, and values. These deep cultural forms are very intricate, almost hidden, because they are personal, individual, possibly collective but multifaceted and because they do not necessarily fit the traditional social norms or the fixed cultural standards. For example, in past decades, Latinos valued large families, living with their parents and grandparents in the same house. However, younger Latino generations today value their independence and want to live on their own. Shaules (2007) observes that “in many intercultural contexts, deep culture is not noticed or understood in any profound sense [because] it constitutes the most fundamental challenge of cultural learning” (p. 12). Hence, deep culture often causes misunderstanding and confusion.

Culture Is Transformative, Not Only Static

Traditionally, the EFL field has considered culture to be a static entity that represents the main collective sociocultural norms, lifestyles, and values that are learned, shared, and transmitted by the people of a community (e.g., the British value punctuality, Americans are workaholics). However, these elemental visions not only tend to create stereotypes but are inaccurate in the current process of global communication given that culture is in constant transformation in multiples ways. It is dangerous to generalize that all of the people of a community “share” and follow the exact same established sociocultural norms with homogeneous compliance. Similarly, it is a mistake to believe that each culture is unalterable and fixed with its own norms and traditions, given that history itself has shown that one nation can indirectly or directly influence and change another and cause cultural alterations. Such are the cases of the British imperialism that exerted political power in India in the 18th century when England became the dominant culture and India the submissive culture, and the impact of the American dream in Latin America through international mass media in our contemporary age. In this sense, culture is a relative concept, not an absolute one, because it transforms over time and among people (Greenblatt, 1995; Levy, 2007). In fact, human beings are inclined to impose or change culture as they face or question cultural realities related, for instance, to oppression, politics, social conflicts, and human rights.

Culture Is Contentious, Not Only Congratulatory

EFL education has also focused on teaching culture in celebratory or neutral terms by emphasizing the most emblematic elements that define a cultural group and by spreading the idea that all cultures of the world happily coexist through mutual respect and tolerance. Therefore, learners create safe, celebratory opinions of the target cultures because they are never taught that defects in and deviations from the models of the “correct” cultural behavior also exist. Learners are taught to appreciate positive characteristics of other nations, such as that Americans are well-organized, the British enjoy having tea every afternoon, and Japanese people are humble. Congratulatory views also underline the study of tourist sites, the lives of famous celebrities, the main human achievements of a country, and tips on how to survive as a tourist in a foreign country.

Contradictorily, Graff (1992) and Hames-Garcia (2003) state that teachers should avoid self-congratulatory approaches to culture, history, and identity in their pedagogy because celebratory discourses are one-sided in that they do not allow students to learn about the true conflictive sociocultural realities of a nation. Instead, approaches to culture and identity should promote a more critical approach through “debates” and “models of controversy and conflict” (Hames-Garcia, 2003, p. 32) against oppression, injustice, and power. In this sense, culture should be taught in the EFL classroom from a contentious and controversial perspective in such a way that it explores the deep, complex elements of culture. This approach helps students become more critical about the controversial cultural dynamics that exist in every nation. Examples of possible debatable topics can be the hegemony of the US in the political affairs of many nations of the world, the tendency of some Latin American presidents to be reelected and impose their power ad infinitum, and even the marginalization of minority groups such as gays, the disabled, and elderly citizens in capitalistic societies, aspects that are classified as confrontational topics of deep culture. Tudor (2001) affirms that teaching materials cannot be neutral because they have to reflect a “set of social and cultural values which are inherent in their make-up . . . and explain a value system, implicitly or explicitly” (p. 73). Accordingly, learners should be encouraged to study those implicit meanings through critical approaches based on debate and contestation rather than just learning passively about the neutral and congratulatory aspects that characterize a given community.

Culture Is Heterogeneous, Not Only Homogeneous

Similar to the previous features, culture is seen in the EFL classroom as a homogeneous entity in which all of its components are studied in equal and generalized terms. Atkinson (1999) refers to this form of culture as “geographically distinct” and “relatively unchanging” (p. 626) and as a set of rules that regulate all individuals’ behavior in a community uniformly as if they were identical. As a result, learners have a tendency to create standardized generalizations of the target culture because they are never given the chance to consider that there are exceptions to the cultural norm. Consequently, it is important to recognize that there are also subgroups and subcultures within a particular society with their own values and ideologies that differ from those of the dominant group and that can help learners reflect on issues related to gender, ethnicity, identity, social class, and power, that is, to understand the heterogeneous and hybrid value that all cultures of the world encompass.

The concept of heterogeneity is closely related to the transformation of culture. The fact that a given community changes because of the influences of other nations or transforms itself because of the range of internal practices and the diverse individual and collective ideologies of its people demonstrates that culture is not superficial and static; it is more complex than it appears to be at first sight. If culture is naturally transformative and heterogeneous, EFL teachers should ponder whether what they teach in the language classroom, as Tudor (2001) suggests, are the real, deep intricacies or the “stereotypical” and superficial forms of a culture.

It is concluded then that culture goes beyond static, surface, congratulatory, and homogeneous principles that only constitute initial and limited standpoints for understanding people from backgrounds different from our own. Guest (2002) identifies a number of problems when teaching the target culture from these basic principles, naming the creation of stereotypes, the failure to reflect about complex realities, and the propagation of intercultural boundaries and misunderstanding. To avoid this limited approach to culture, teachers should study it from a more critical standpoint because learners are then able to understand that it is transformative, deep, contentious, and heterogeneous. In this way, learners will be able to develop critical ICC.

English Textbooks Analysis

Led by the previous insights, the analysis of the three EFL communicative textbooks attempts to identify the levels of surface and deep cultural content that they incorporate in their units and how they can help learners build ICC to make them aware of cultural differences in the current globalized society in which they live. The textbooks were analyzed guided by the following question:

Which surface or deep cultural topics do EFL communicative textbooks contain?

Criteria for the Selection of the Textbooks

The textbooks chosen for the analysis were designed by international British and American publishing houses and correspond to three levels: basic, intermediate, and advanced English. They are used in many countries worldwide for various EFL contexts. They have also been used in the language programs at three universities in Bogotá, Colombia, for a number of years. This was an important decision because the texts were implemented as a means to prepare EFL pre-service teachers to become future teachers in the country. Furthermore, it was important to analyze how these instructional materials included culture and helped pre-service teachers to develop ICC.

The names of the textbooks are not revealed because the idea is not to create prejudicial positions about their reputations but rather to offer EFL teachers some critical bases of analysis for how to more appropriately address culture as it is presented in textbooks. This examination will also be an opportunity to envision alternative materials that could facilitate the teaching of deep cultural content in the classroom.

Analysis Procedure

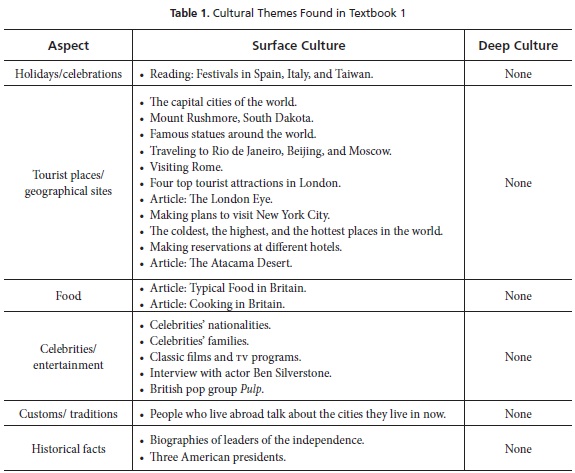

To answer the question that led this analysis, every single page and unit of the textbooks was examined to detect those activities in which culture was incorporated. Each topic was classified into two categories: surface or deep culture. All of the static aspects such as holidays, geographical sites, food, and important people were classified as surface culture, whereas all of the invisible aspects that appeared to be complex to approach were classified as deep culture. For instance, Table 1 shows that for the aspect holidays/celebrations, Textbook 1 included a reading about festivals in Spain, Italy, and Taiwan, and in the aspect important people, celebrities, and entertainment, the same book contained an interview with British actor Ben Silverstone. In addition, all of the cultural themes were examined according to the following features:

- Topics of surface culture: characterized as being static, congratulatory, neutral, and homogeneous.

- Topics of deep culture: characterized as being transformative, complex, contentious or congratulatory, and heterogeneous.

These features are explained in detail in the analysis of each textbook.

Findings

The Cultural Component in Textbook 1 (Basic Level)

The analysis of Textbook 1 shows that all of the themes presented in each unit belong to the level of surface/visible culture. It contains six main neutral/celebratory aspects: holidays, tourist places, food, celebrities, traditions, and historical facts (see Table 1). There is no information related to deep culture, which means that the text is limited in promoting ICC.

The themes are celebratory because they honor the emblematic symbols and happenings of different nations. For instance, the article about festivals that appears in unit three describes The Tomatina festival in Spain, the Carneval ed’elverea in Italy, and The Water Festival in Taiwan. It provides positive descriptions of the traditional activities people do during those celebrations. As an example, this is the description of the Water Festival in Thailand:

Thailand has a Water Festival (Songkran) every April to celebrate the New Year. It starts on 13th April and lasts for two days. People throw water at each other all day and all night. (Sample taken from Textbook 1)

Though this textbook envisions an intercultural scope of countries such as Spain, Italy, Taiwan, and Brazil, it focuses primarily on congratulatory descriptions of the target main culture that the textbook represents: England. It includes information about top British tourist attractions in London such as the London Eye, the Tower of London, and the Buckingham Palace and facts about British celebrities, architecture, and food, which are presented throughout the whole book. With these features, the textbook seems to proclaim a sense of ethnocentrism by presenting England’s most outstanding cultural symbols.

Additionally, the people from the different countries that appear in the textbook possess a neutral celebratory attitude. They are cheerful tourists going sightseeing, traveling all over the world, going shopping, and having nice, safe conversations, implying that although the peoples of the world are all different, they are able to live together because of their intercultural harmonious understanding. The following phone conversation between a travel agent and a British woman who is planning to visit New York City shows neutral/congratulatory content:

Lisa: Hello?

Peter: Hi! Lisa? This is Peter Douglas from Changing Holidays.

Lisa: Oh! Hello!

Peter: What are your holiday plans for next week?

Lisa: Er...I’m going to fly to New York with my boyfriend, Jon.

Peter: Great. And where are you going to stay?

Lisa: We’re going to stay in the Hotel Athena in Manhattan.

Peter: What are you going to do in New York, Lisa?

Lisa: We’re going to go shopping...we want to see the Empire State Building, the Statue of Liberty, Central Park...

This conversation notes tourist places as a congra-tulatory paramount topic. New York City is described as an attractive holiday destination with tall buildings and interesting sites. It shows a superficial view of the American dream based on materialism (going shopping and going sightseeing) and pictures the United States as the land of freedom represented by the Statue of Liberty. These topics lead to fixed superficial stereotypes of geographical sites because, as Hinkel (2001) asserts, this type of cultural information is unchanged and easily observable. Therefore, the main goal of Textbook 1 appears to be to provide relevant information about the emblematic aspect of culture/s. These elements confirm that culture is only considered static, neutral, and homogeneous in that learners are not encouraged to address any of the deeper elements of culture.

The question that arises here is if this congratulatory/static view of culture is sufficient to prepare EFL learners to become intercultural individuals in this globalized world. In fact, most topics displayed in Textbook 1 appear not to foster interculturality but rather to provide learners with general information to be able to “survive” happily as tourists in a foreign country. We cannot say that this survival travel guidance enables ICC development. ICC embraces the understanding of more profound meanings and contents.

The Cultural Component in Textbook 2 (Intermediate Level)

The analysis of Textbook 2 found similar features to Textbook 1 in regards to the six main neutral aspects of visible culture: holidays, tourist places, celebrities, traditions, literature, and general information. However, whereas Textbook 1 included food and historical facts as part of its six topics, Textbook 2 included two different ones, literature and general information (see Table 2). Additionally, Textbook 1 is overloaded with topics related to tourist places and geographical sites, but Textbook 2’s top cultural content is holidays and celebrations.

In contrast to Textbook 1, Textbook 2 incorporates two tasks that require learners to address aspects of deep culture (see Table 2, Customs/traditions). One of the tasks is to listen to a radio show in which three guests from Thailand, Dubai, and Nepal answer callers’ questions about table manners, greetings, clothing, male and female behavior, taboos, and offensive behaviors. Interestingly, EFL learners can learn the following information:

- In Thailand, tourists should not touch anyone’s head because Thais believe that the mind is where each person’s soul lives and it is disrespectful to touch it;

- Thais greet each other by putting their palms together on the chest and bowing slightly while uttering an accepted greeting;

- Tourists in Dubai should not take pictures of Muslim women because that is offensive;

- People in Nepal eat with their right hand, never with silverware;

- It is forbidden to eat beef in Hindu and Buddhist homes.

This task provides learners with deep elements of culture that would be difficult to understand if one were not aware of those complex intricacies and would cause cultural misunderstanding. Nevertheless, it is a significant problem that a book with ten units contains merely two tasks that address deep culture. This factor confirms that static views of the target culture dominate the language classroom, as observed in Table 2.

Moreover, although the radio show includes issues of deep culture, it still highlights a congratulatory tourist version of understanding other nations’ traditions in harmonious and safe terms. In fact, the purpose of the radio show is that the three guests from Thailand, Dubai, and Nepal answer the questions of three tourists who are planning to visit those countries and want to behave correctly while they are there. This task puts into question the extent to which textbooks prepare EFL learners with information that will allow them to live successfully as foreigners/tourists in strange lands or provide them with the actual ICC to manage cultural differences wisely and critically. Just because learners are given some useful travel tips does not ensure their development of firm ICC.

More to the point, the great emphasis on elements of surface culture in Textbooks 1 and 2 leads us to conclude that they often promote a received view of culture (Atkinson, 1999) that conceives of cultural manifestations as a list of unchanging and homogeneous rules that determine a country’s behaviors and there is no room for exceptions. The learners receive and store cultural information in their minds, but they are neither told about possible deviations from the rules nor asked about their critical opinions regarding the differences by comparing their own and the target cultures. For instance, in relation to the radio show, instead of assuming a received view of culture, it would be interesting to enrich the task by encouraging learners to research deeper aspects such as what would be the social consequences if a left-handed person could not eat with his/her right hand in Nepal, what issues of masculine hegemony are behind the fact that Muslim women cannot be photographed, and what religious, political, and economic implications are hidden under the ban on eating beef in Nepal. It is a fact that in the present, Nepal is no longer a country with one religion, Hinduism, and therefore, not everyone in Nepal strictly obeys the rule of not eating beef. Equally, cows that have been sacred for most Nepalese are eventually sold to India to be slaughtered by beef suppliers and are sold to Muslims, Christian communities, and many restaurants for tourists. That is to say, in the end, old sacred cows become part of an underground beef trade between Nepal and India because they are considered merchandise rather than sacred religious symbols. These examples show that the study of culture should envision not only a received and congratulatory view but also a deeper and even contentious analysis of why those cultural norms exist and why there are deviations from them. Discussing these complex cultural variations that define a country might empower EFL learners become more critical intercultural learners, a task that EFL communicative textbooks have still not achieved.

The Cultural Component in Textbook 3 (Advanced Level)

Textbook 3 equally displays elements of surface culture. The most prominent topic that appeared throughout the textbook is celebrities and entertainment. It includes six main topics: tourist sites, famous people, traditions, legends, general information, and basic historical facts (see Table 3). It also contains a series of short culture notes such as Go, a popular game on a square board, the meaning of a piggy bank, and the meaning of the stork as associated with childbirth, as observed in these examples:

Culture note: A piggy bank is a container used mainly by children to store coins. Piggy banks are used to encourage good saving and spending habits. The pig must be broken open for the money to be retrieved, forcing the child to justify his or her decision. (Unit 3)

Culture note: The stork is a type of bird that has traditionally been associated with childbirth in western folk tales. In the tales, the stork delivers newborn babies to their mothers. (Unit 8)

The analysis of these culture notes suggests that they are more oriented to explaining the meaning of new vocabulary that appears in the readings than actually teaching salient cultural facts. The piggy bank and the stork, for instance, are common concepts shared in many nations that do not necessarily imply deep cultural understanding. Moreover, these short culture notes do not appear in the textbook directly. They appear in the teacher’s guide and are optional for the teachers to address during the study of each unit. Indeed, Textbook 3 is primarily concerned with neutral, universal topics about our contemporary daily lives, including pets, shopping, well-known mysteries, stressful situations, and unusual hobbies, among others. Elements of deep culture are completely absent, so the textbook fails to promote critical ICC.

Keeping in mind the question that guided this analysis, Textbook 3, similar to the previous textbooks, adopted a received, congratulatory, neutral, and static view of the few cultural references that it contains, which are considerably scarcer than the contents of Textbooks 1 and 2. Certainly, the topics in the three textbooks do not provide EFL learners with, at least, the basic skills to become critical intercultural citizens of the world, which is a disadvantage because they are influential textbooks designed by prestigious publishing houses to be studied by millions of learners worldwide.

What Teachers Should Do to Address Deep Culture in the EFL Classroom

In view of the fact that textbooks only approach static and congratulatory elements of surface culture, this section presents two examples in which deep, transformative, and heterogeneous views of the target culture can be addressed in the classroom. They will give teachers a general idea of how to choose and design tasks that aim at developing learners’ critical ICC, given that our analysis so far has shown that teachers should not depend completely on the received visions of culture that are presented in textbooks. With these examples, teachers are encouraged to discuss with their students culture-based material that includes not only celebrations, important cities, tourist places, and famous people, among others, but issues related to difference, power, ideology, identity, and even resistance, that is, elements of deep culture. The examples are designed for undergraduate EFL learners at the university level in Colombia. However, they can be adapted to suit the needs of other learners in other academic contexts.

Example One: Native-Americans, Victims of Exclusion and Abusive Power

The first cultural topic relates to the Nez Perce tribe, one of the many Native-American tribes that were attacked and displaced by the white men’s campaigns against American Indians in the Great Plains (1874-1875) during the time of expansionism. Students can work on the study guide (Appendix A) that will help them approach this topic from a critical intercultural standpoint. As observed, the language in the reading and the questions are written at a basic level that would be readable in an elementary or intermediate-level English course.

As the study guide suggests, the questions in Activity I: “Understanding the Context,” help learners reflect on the situation of Native Americans, a minority group in the US that was a victim of exclusion and violence by the white men’s hegemony. It also helps learners compare possible situations of displacement and social exclusion between minority groups within their own countries and the situation of the Nez Perce. By establishing intercultural connections, learners are expected to address issues of deep and contentious cultural conflicts such as injustice, violence, abuse of power, and domination as well as transformative aspects of culture such as the influence of the white men on indigenous people, the Nez Perce’s resistance to oppression and displacement, and personal and collective ideas about honor. The readings in Section II, “Discovering Cultural Facts,” which includes the original version of Chief Joseph’s speech “I Will Fight No More Forever,” and Section III, “Critical Reactions to the Conflict” encourage learners to reflect insightfully on complex topics of culture. Some questions of main importance, for instance, 5, 6, and 7 in the last section, attempt to incite learners to express personal opinions about why the chief of the Nez Perce tribe surrendered and what realities of pain and suffering this Native American minority group endured because of white men’s tyranny.

As observed, the topic in the study guide intends to demonstrate that although the US has historically been a multicultural society, it has lacked any full understanding of intercultural awareness. From a contentious critical position rather than a congratulatory one, EFL learners are encouraged to discuss at the level of their language proficiency that despite many people’s belief that the US is the “Land of Opportunity,” where diverse communities live happily together, it is a place where discrimination and inequity have been historically practiced, as was the case with the Nez Perce tribe. It is evident that Native Americans, African-Americans, Asian-Americans, and Latinos have been deprived of equal status in US society through history because white men have considered themselves a superior race. Jay and Jones (2005) observe that white men and western cultures have legitimized overriding power in America and in the rest of the world and that discrimination against other racial communities comes from the colonial imperialist thought that “White people possess supposedly unique characteristics, qualities purportedly making them both a ‘superior race’ and the ‘norm’ by which others are judged” (p. 110). By helping learners become aware of the complicated, contentious, and non-celebratory elements of culture in the topic that is presented here and in many other similar topics and contexts, they might become progressively better able to develop critical ICC.

Example Two: Single-Parent Families: A Cultural Decline?

Critical ICC can also be developed with contemporary topics that are more closely related to learners’ own cultures. The study guide (Appendix B) addresses a cultural phenomenon that has impacted and affected many nations in the world: the proliferation of single-parent families. This controversial topic is a great opportunity for students to discuss intricate and complicated issues that demonstrate that culture is not always static, congratulatory, and homogeneous. With this topic, upper intermediate and advanced EFL learners are challenged to express their opinions about the traditional model of the family and to what extent that model is actually preserved or transformed in real life by the people of a culture. The questions in the first activity, “Understanding the Context,” invite learners to problematize the fact that not all families in many backgrounds necessarily follow the cultural construct that a family must consist of one father, one mother, and some children. During the discussion, learners might refer to social, economic, and religious standards that enact an ideal family model but that in real life are not always embraced and why increasing numbers of families are headed by single parents in our contemporary age.

Similarly, Activity II, “Discovering Cultural Facts,” shows learners an article about single-parent families in the US so that students understand how this cultural phenomenon is also present in other countries. Section III, “Critical Reactions to the Conflict,” similarly encourages students to observe deep cultural motifs that could cause the decline or improvement of their own communities (e.g., how young people’s views about marriage and patriarchal masculinity have caused the spread of single-parent families). Similarly, learners are invited to do research about the value of the family in foreign countries—specifically, China, the Zulu tribe in Africa, and Nepal—and even to consider the sociocultural implications of why never-married families and same-sex-parent families might transgress the cultural norm (Appendix B, Activity III).

Final Considerations

This article has shown that the communicative textbooks used in undergraduate language programs at some universities and in other EFL settings mostly lack elements of deep culture that might help learners to develop ICC. Most of their topics belong to surface culture and are based on static, congratulatory, and homogeneous notions, all emblematic elements of the foreign culture/s. It is concluded that teachers are called on to consider teaching alternatives by means of seeking, adapting, and, if possible, designing culture-based materials through which EFL learners are encouraged to address deep culture in such a way that, instead of a received version of culture, they assume a critical position towards cultural realities as transformative and heterogeneous.

This article has discussed that collective and personal issues related to power, hegemony, exclusion, discrimination, and oppression as well as resistance, independence, inclusion, individuality, and justice are multidimensional expressions of deep culture that oppose the fixed and idealistic cultural constructs imposed by any given society. These issues and many other complicated cultural topics, for instance, collective and individual attitudes towards dating, honesty, religion, sex roles, independence, money, education, injustice, and globalization, can be discussed in the EFL classroom.

Teachers and material makers should take advantage of real-life resources such as newspapers, literature, documentaries, history, and movies to study topics related to race, discrimination, social class struggle, and human rights. Equally, they can create awareness through debates about how cultural traditions can be transformed or affected by, for example, the influence of technology, cyber-bullying, talk shows, reality shows, and television in general. Learners can also be encouraged to do basic ethnographic research on minority groups, urban tribes, personal lifestyles, and marginalized groups. As Olaya and Gómez (2013) suggest, “not only celebrating cultures, but establishing critical views can empower [learners] to develop critical ICC” (p. 62), even if they have to be exposed to deviant, non-celebratory, and questionable matters that might cause the reevaluation of preestablished and sometimes unjust cultural standards.

References

Atkinson, D. (1999). TESOL and culture. TESOL Quarterly, 33(4), 625-654. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587880.

Babusci, R., & Guy, D. (Eds.) (1991). Prentice Hall Literature: The American experience. New Jersey, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Bachman, L. F. (1999). Fundamental considerations in language testing. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Banks, J. A. (2004). Introduction: Democratic citizenship education in multicultural societies. In J. A. Banks (Ed.), Diversity and citizenship education: Global perspectives (pp. 3-15). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Byram, M., Gribkova, B., & Starkey, H. (2002). Developing the intercultural dimension in language teaching: A practical introduction for teachers. Strasbourg, FR: Council of Europe. Retrieved from http://www.lrc.cornell.edu/director/intercultural.pdf.

Graff, G. (1992). Beyond the culture wars: How teaching the conflict can revitalize American education. New York, NY: Norton.

Greenblatt, S. (1995). Culture. In F. Lentricchia & T. McLaughlin (Eds.), Critical terms for literature study (pp. 225-32). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Guest, M. (2002). A critical “checkbook” for culture teaching and learning. ELT Journal, 56(2), 154-161. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/56.2.154.

Hames-Garcia, M. R. (2003). Which America is ours? Marti’s “truth” and the foundations of “American literature.” MFS Modern Fiction Studies, 49(1), 19-53. https://doi.org/10.1353/mfs.2003.0006.

Hinkel, E. (2001). Building awareness and practical skills to facilitate cross-cultural communication. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (3rd ed., pp. 443-358). Boston, MA: Heinle Cengage Learning.

Jay, G., & Jones, S. E. (2005). Whiteness studies and the multicultural literature classroom. MELUS, 30(2), 99-121. https://doi.org/10.1093/melus/30.2.99.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2008). Cultural globalization and language education. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Levy, M. (2007). Culture, culture learning and technologies: Towards a pedagogical framework. Language Learning and Technology, 11(2), 104-127.

Olaya, A., & Gómez, L. F. (2013). Exploring EFL pre-service teachers’ experience with cultural content and intercultural communicative competence at three Colombian universities. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 15(2), 49-67.

Savignon, S. J. (1997). Communicative competence: Theory and classroom practice (2nd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Savignon, S. J. (2001). Communicative language teaching for the twenty-first century. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (3rd ed., pp. 31-45). Boston, MA: Heinle Cengage Learning.

Shaules, J. (2007). Deep culture: The hidden challenges of global living. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Single-parent families. (n.d.). Retrieved and adapted from Encyclopedia of Children’s Health. http://www.healthofchildren.com/S/Single-Parent-Families.html.

Tudor, I. (2001). The dynamics of the language classroom. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

About the Author

Luis Fernando Gómez Rodríguez holds a PhD in English Studies from Illinois State University (USA) and a MA in education from Carthage College (USA). He is an associate teacher at Universidad Pedagógica Nacional. His research interests are intercultural competence, literature, and critical issues in EFL education.

Appendix A: I Will Fight No More Forever (1877)

- Understanding the Context

- Do you know any information about the Native Indians or a minority group in your country? In which conditions do they live? Does the government help them?

- Do you know any Native American tribes of the US? What information do you know about them? Where do they live at present? Where did they live in the past?

- Do some research into the history of the Nez Perce, a Native American tribe. What are their traditions and problems?

- Discovering Cultural Facts

- Read the following passage about the Nez Perce, a Native American tribe of the US, and their relationships with the American government in the 19th century. Was it a good or bad relationship?

- Read Chief Joseph’s Surrender Speech “I Will Fight No More Forever” (1877) after the white men attacked and killed many people from his Indian tribe. What is the tone of the speech?

- Critical Reactions to the Conflict

- What started the war between the Nez Perce and the white men? Who do you think was right?

- What was the attitude of the white men toward Native Americans?

- What aspects of injustice and oppression can you see between the Native American and white cultures?

- What does Chief Joseph want to have time for?

- Mention three reasons Chief Joseph has for deciding to “fight no more forever.”

- What do you think is the purpose of Chief Joseph’s speech?

- Is there or was there a similar situation between any minority group and the government in the history of your country? What was the conflict? What do you think about that conflict?

The tribe of Chief Joseph (1840-1904), the Nez Perce, was known as peaceful and noble. In 1805, they met Colonel Nelson Miles, who explored the west for President Thomas Jefferson. There were treaties between the white men and the Native Americans, in which the Nez Perce had to accept that the government was the owner of the land. Chief Joseph, the leader of the Nez Perce, refused to sign the treaties because they were unjust. In response, the American government and settlers invaded the Nez Perce’s land, the Wallowa Valley, and forced them to move to a reservation on the Canadian border. Because of this injustice, some Nez Perce disagreed and killed some settlers. The war started, and Chief Joseph and his tribe were defeated and captured in 1877 by Colonel Miles. There were terrible consequences for these Native American people.

I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed. Looking Glass is dead. Toohulhulsote1 is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say no and yes. He who led the young men is dead. It is cold and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, Have run away to the hills And have no blankets, no food. No one know where they are Perhaps they are freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs, I am tired. My heart is sad and sick. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever. (Taken from Babusci & Guy, 1991, pp. 452-455)

1Looking Glass and Toohulhulsote were the names of the chiefs of the Nez Perce tribe.

Appendix B: Single-Parent Families: A Cultural Decline?

- Understanding the Context

- What is the traditional model of the family in your country? Is it the same model in other cultures? Who is the head of the family according to that model? Why? Who has created that model?

- Is the traditional model of the family followed by all the people in your country? Are there any other possible family versions that break the two-parent family model?

- Why do you think the traditional ideal of a family is changing radically in your culture?

- Discovering Cultural Facts

- Read the following passage about the decline of two-parent families in the United States. Then, answer the questions.

- Understanding the Facts

- How many children lived in single-parent families in the US by 2002?

- What reasons increased single-parent families in the early to mid-1920s, in the 1980s, and in 2002 in the US? Can you infer what cultural changes marriage has suffered since the mid-1920s?

- What is the most common type of single-parent family in the US? Is the situation the same in your culture?

- In which way are children from single-parent families disadvantaged compared with two-biological-parent families? What do those disadvantages suggest about the role of the family in a culture?

- Does the article suggest that children born in single-parents families can also be advantaged? In which ways? Would you agree?

- Critical Reactions to the Conflict

- What cultural views do people in your country have about single-parent families? In which ways are children advantaged or disadvantaged because of those views?

- What cultural views do young people have about marriage? Is the situation the same as it was 50 years ago? Why do you think young families tend to divorce more often now than in the past?

- What are the reasons why many young women become single parents in your culture?

- What part do men play in the cultural shift from two-parent to single-parent families?

- Would you agree that the increase in single-parent families could cause a cultural decline? Why?

- Research the family model in these cultures and determine whether that model is still being adopted at present or has suffered changes, as it has in the US, England, India, China, the Zulu tribe in Africa, and Nepal.

- In which ways do these types of families transgress the traditional family model: single-parent families, never-married families, same-sex-parent families?

- What social and/or cultural implications might arise because of the transgressions of that cultural model?

Single-Parent Families: A Cultural Decline?

One out of every two children in the United States will live in a single-parent family before they reach age 18. According to the United States Census Bureau, in 2002, approximately 20 million children lived with only their mother or their father. This is more than one-fourth of all children in the United States.

Since 1950, the number of one-parent families has increased substantially. In 1970, approximately 11 percent of children lived in single-parent families. During the 1970s, divorce became much more common, and the number of families headed by one parent increased rapidly. By 1996, 31 percent of children lived in single-parent families. In 2002, the number was 28 percent.

The reasons for single-parent families have also changed. In the mid-twentieth century, most single-parent families came about because of the death of a spouse. In the 1970s and 1980s, most single-parent families were the result of divorce. In the early 2000s, more and more single parents have never married. Many of these single parents live with an adult partner, sometimes even their child’s other parent. These families are counted by the Census Bureau as single-parent families, although two adults are present.

The most common type of single-parent family is one that consists of a mother and her biological children. In 2002, 16.5 million or 23 percent of all children were living with their single mother. This group included 48 percent of all African-American children, 16 percent of all non-Hispanic white children, 13 percent of Asian/Pacific Islander children, and 25 percent of children of Hispanic origin.

Single-parent families face special challenges, one of which is economic. In 2002, twice as many single-parent families earned less than $30,000 per year compared with families with two parents present. At the opposite end of the spectrum, 39 percent of two-parent families earned more than $75,000 compared with six percent of single-mother families and 11 percent of single-father families.

Social scientists have found that children growing up in single-parent families are disadvantaged in other ways compared with those in two-biological-parent families. Many of these problems are directly related to the poor economic conditions of single-parent families. These children are at risk for the following: lower levels of educational achievement, greater likelihood of becoming teen parents, more conflict with their parent(s), less adult supervision, more frequent abuse of drugs and alcohol, more high-risk sexual behavior, greater likelihood of joining a gang, twice the likelihood of going to jail, greater likelihood of participating in violent crime, greater likelihood of suicide, and twice the likelihood of getting divorced in adulthood. How would these problems affect American society? Would American culture decline?

Despite the fact that children from single-parent families often face a tougher time economically and emotionally than do children from two-biological-parent families, children from single-parent families can grow up to do well in school and maintain healthy behaviors and relationships. (Retrieved and adapted from Encyclopedia of Children’s Health: http://www.healthofchildren.com/S/Single-Parent-Families.html)

References

Atkinson, D. (1999). TESOL and culture. TESOL Quarterly, 33(4), 625-654. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587880

Babusci, R., & Guy, D. (Eds.) (1991). Prentice Hall Literature: The American experience. New Jersey, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Bachman, L. F. (1999). Fundamental considerations in language testing. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Banks, J. A. (2004). Introduction: Democratic citizenship education in multicultural societies. In J. A. Banks (Ed.), Diversity and citizenship education: Global perspectives (pp. 3-15). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Byram, M., Gribkova, B., & Starkey, H. (2002). Developing the intercultural dimension in language teaching: A practical introduction for teachers. Strasbourg, FR: Council of Europe. Retrieved from http://www.lrc.cornell.edu/director/intercultural.pdf

Graff, G. (1992). Beyond the culture wars: How teaching the conflict can revitalize American education. New York, NY: Norton.

Greenblatt, S. (1995). Culture. In F. Lentricchia & T. McLaughlin (Eds.), Critical terms for literature study (pp. 225-32). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Guest, M. (2002). A critical “checkbook” for culture teaching and learning. ELT Journal, 56(2), 154-161. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/56.2.154

Hames-Garcia, M. R. (2003). Which America is ours? Marti’s “truth” and the foundations of “American literature.” MFS Modern Fiction Studies, 49(1), 19-53. https://doi.org/10.1353/mfs.2003.0006

Hinkel, E. (2001). Building awareness and practical skills to facilitate cross-cultural communication. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (3rd ed., pp. 443-358). Boston, MA: Heinle Cengage Learning.

Jay, G., & Jones, S. E. (2005). Whiteness studies and the multicultural literature classroom. MELUS, 30(2), 99-121. https://doi.org/10.1093/melus/30.2.99

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2008). Cultural globalization and language education. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Levy, M. (2007). Culture, culture learning and technologies: Towards a pedagogical framework. Language Learning and Technology, 11(2), 104-127.

Olaya, A., & Gómez, L. F. (2013). Exploring EFL pre-service teachers’ experience with cultural content and intercultural communicative competence at three Colombian universities. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 15(2), 49-67.

Savignon, S. J. (1997). Communicative competence: Theory and classroom practice (2nd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Savignon, S. J. (2001). Communicative language teaching for the twenty-first century. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (3rd ed., pp. 31-45). Boston, MA: Heinle Cengage Learning.

Shaules, J. (2007). Deep culture: The hidden challenges of global living. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Single-parent families. (n.d.). Retrieved and adapted from Encyclopedia of Children’s Health. http://www.healthofchildren.com/S/Single-Parent-Families.html

Tudor, I. (2001). The dynamics of the language classroom. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Rong Xiang, Vivian Yenika-Agbaw. (2021). EFL textbooks, culture and power: a critical content analysis of EFL textbooks for ethnic Mongols in China. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 42(4), p.327. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2019.1692024.

2. María del Mar Bernabé Villodre, José Manuel Azorín-Delegido, Vladimir Martínez-Bello. (2024). Representations of cultural diversity in music education textbooks: a critical and comparative analysis. Multicultural Education Review, 16(1), p.25. https://doi.org/10.1080/2005615X.2024.2338977.

3. Catalina Suárez Valencia, Diana Marcela Patiño Rojas, Alexander Ramirez Espinosa. (2026). Contenidos culturales y competencia comunicativa intercultural en dos manuales de nivel intermedio de una serie de inglés como lengua extranjera. Revista Virtual Universidad Católica del Norte, (77), p.42. https://doi.org/10.35575/rvucn.n77a3.

4. Mostafa Morady Moghaddam, Mohammad Hossein Tirnaz. (2023). Representation of Intercultural Communicative Competence in ELT Textbooks: Global Vs. Local Values. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 52(2), p.191. https://doi.org/10.1080/17475759.2022.2152076.

5. Leoni Dörfel, Rieke Ammoneit, Carina Peter. (2024). Diversity unveiled: a critical analysis of geography textbooks and their global representation. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, , p.1. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2024.2363639.

6. Ömer Gökhan Ulum, Dinçay Köksal. (2021). A critical inquiry on the ideological and hegemonic practices in EFL textbooks. Multicultural Learning and Teaching, 16(1), p.45. https://doi.org/10.1515/mlt-2019-0005.

7. Ömer Gökhan Ulum. (2025). Syrian Lives Matter in an EFL speaking class: An interdisciplinary approach to language, culture, and social justice. Teaching and Teacher Education, 160, p.105040. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2025.105040.

8. Benjamín Cárcamo Morales. (2020). Readability and types of questions in Chilean EFL high school textbooks. TESOL Journal, 11(2) https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.498.

9. Gabriel Sánchez-Sánchez, Eduardo Encabo-Fernández. (2023). New Approaches to the Investigation of Language Teaching and Literature. Advances in Educational Technologies and Instructional Design. , p.1. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-6684-6020-7.ch001.

10. Yaping Tang, Li Liu. (2026). Cultural representation in primary ELT textbooks: an approach of multimodal discourse analysis. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 47(1), p.54. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2025.2484349.

11. Alix Norely Bernal Pinzón. (2020). Authentic Materials and Tasks as Mediators to Develop EFL Students’ Intercultural Competence. HOW, 27(1), p.29. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.27.1.515.

12. Thi Duyen Phuong, Raf Vanderstraeten. (2024). The ‘Hidden Curriculum’ of Vietnam’s English School Textbooks. SpringerBriefs in Education. , p.47. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-97-1196-3_3.

13. Ömer Gökhan Ulum, Dinçay Köksal. (2019). Ideology and Hegemony of English Foreign Language Textbooks. , p.1. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-35809-9_1.

14. Ömer Gökhan Ulum, Dinçay Köksal. (2019). Ideological and Hegemonic Practices in Global and Local EFL Textbooks Written for Turks and Persians. Acta Educationis Generalis, 9(3), p.66. https://doi.org/10.2478/atd-2019-0014.

15. Virginia Kwok. (2019). Exploring Pedagogy Enhancement with eLearning for 21st Century Language Education. Proceedings of the 2019 11th International Conference on Education Technology and Computers. , p.47. https://doi.org/10.1145/3369255.3369279.

16. Astrid Núñez-Pardo. (2020). Inquiring into the Coloniality of Knowledge, Power, and Being in EFL Textbooks. HOW, 27(2), p.113. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.27.566.

17. Mónica Patarroyo Foncesa. (2017). Textbooks Decontextualization within Bilingual Education in Colombia. Enletawa Journal, 9(1) https://doi.org/10.19053/2011835X.7541.

18. Lili Zhang, Christopher A Smith. (2024). Neoliberal, trouble-free worlds for an aspirational middle-class in Chinese EFL publications: A multimodal critical discourse analysis. Discourse & Communication, 18(4), p.592. https://doi.org/10.1177/17504813241237377.

19. Hajar Abdul Rahim, Ali Jalalian Daghigh. (2020). Locally-developed vs. Global Textbooks: An Evaluation of Cultural Content in Textbooks Used in ELT in Malaysia. Asian Englishes, 22(3), p.317. https://doi.org/10.1080/13488678.2019.1669301.

20. Tahan H. J. Sihombing, Mai Xuan Nhat Chi Nguyen. (2025). Cultural content of an English textbook in Indonesia: text analysis and teachers’ attitudes. Asian Englishes, 27(1), p.227. https://doi.org/10.1080/13488678.2022.2132131.

21. Jackie F. K. Lee, Xinghong Li. (2020). Cultural representation in English language textbooks: a comparison of textbooks used in mainland China and Hong Kong. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 28(4), p.605. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2019.1681495.

22. DUVAN MOSQUERA. (2023). Teacher-Made Materials Based on Meaningful Learning to Foster Writing Skills.. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 25(1), p.17. https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.18825.

23. Astrid Núñez-Pardo. (2020). Inquiring into the Coloniality of Knowledge, Power, and Being in EFL Textbooks. HOW, 27(2), p.113. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.27.2.566.

24. Jairo Eduardo Soto-Molina, Pilar Méndez. (2020). Linguistic Colonialism in the English Language Textbooks of Multinational Publishing Houses. HOW, 27(1), p.11. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.27.1.521.

25. Uthman Alzuhairy. (2025). Language Education in Saudi Arabia: Challenges and Opportunities in Language Pedagogy and Policy. English Language Teaching: Theory, Research and Pedagogy. , p.73. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-91443-0_5.

26. Anamaria Sagre, Leonardo Pacheco Machado, Yurisan Tordecilla Zumaquè. (2024). Intercultural teaching practices in the EFL classroom: The case of non‐elite communities. TESOL Journal, 15(2) https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.768.

27. Maura Klenner-Loebel, Juan Carlos Beltrán-Véliz, Trevor Driscoll. (2026). Araucanía Chilean EFL Teachers’ Beliefs Regarding Their Intercultural Mediator Role. Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 28(1), p.89. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v28n1.117794.

28. Monireh Azimzadeh YİĞİT, Emrah DOLGUNSÖZ. (2023). A Cross-Cultural Analysis of a Turkish EFL Textbook: Hu and McKay's Analytic Framework. RumeliDE Dil ve Edebiyat Araştırmaları Dergisi, (36), p.1321. https://doi.org/10.29000/rumelide.1369167.

29. ERDOST YASTIBAŞ AHMET. (2021). INCLUSIVE EDUCATION AND INCLUSIVE VALUES IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE COURSE BOOKS. i-manager's Journal on School Educational Technology, 16(3), p.1. https://doi.org/10.26634/jsch.16.4.17810.

30. Beatriz Chaves-Yuste. (2023). La literatura como instrumento de aprendizaje del inglés como lengua extranjera. Enunciación, 28, p.131. https://doi.org/10.14483/22486798.20280.

31. Catalina Jaramillo Cárdenas. (2023). Incorporating an intercultural path in the National Bi/multilingual Program. The challenge. Lenguaje, 51(2), p.416. https://doi.org/10.25100/lenguaje.v51i2.12646.

32. Claudia Patricia Gutiérrez. (2022). Learning English From a Critical, Intercultural Perspective: The Journey of Preservice Language Teachers. Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 24(2), p.265. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v24n2.97040.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.