Published

Adult EFL Reading Selection: Influence on Literacy

Procesos de selección de lecturas en estudiantes adultos de inglés como lengua extranjera y su influencia en la habilidad lectora

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n1.49943Keywords:

Behavioral patterns, engagement, motivation, perceptions, reading habits, self-selection (en)autoselección, compromiso, hábitos de lectura, motivación, patrones de comportamiento, percepciones (es)

This paper is about the impact of systematic reading selection used to promote English as foreign language learning in adult students. A qualitative action research methodology was used to carry out this project. Ten class sessions were designed to provide students an opportunity to select texts according to criteria based upon their language levels and personal/professional interests. The findings align with three categories of influence: motivation, engagement, and contextualization/interpretation of readings. The main objective of this project was to see how the students’ text selection processes, guided by systematically designed criteria and elaborated strategies, influenced learning and acquisition in terms of motivation, perceptions, and opinions towards reading in English.

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n1.49943

Adult EFL Reading Selection: Influence on Literacy*

Procesos de selección de lecturas en estudiantes adultos de inglés como lengua extranjera y su influencia en la habilidad lectora

Juan Sebastián Basallo Gómez**

Colegio Fontan, Bogotá, Colombia

This article was received on April 1, 2015, and accepted on July 10, 2015.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Basallo Gómez, J. S. (2016). Adult EFL reading selection: Influence on literacy. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 18(1), 167-181. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n1.49943.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This paper is about the impact of systematic reading selection used to promote English as foreign language learning in adult students. A qualitative action research methodology was used to carry out this project. Ten class sessions were designed to provide students an opportunity to select texts according to criteria based upon their language levels and personal/professional interests. The findings align with three categories of influence: motivation, engagement, and contextualization/interpretation of readings. The main objective of this project was to see how the students’ text selection processes, guided by systematically designed criteria and elaborated strategies, influenced learning and acquisition in terms of motivation, perceptions, and opinions towards reading in English.

Key words: Behavioral patterns, engagement, motivation, perceptions, reading habits, self-selection.

Este artículo aborda el impacto de la selección sistemática de lectura usada para promover el aprendizaje del inglés como lengua extranjera en estudiantes adultos. En este proyecto se utilizó la metodología de investigación-acción cualitativa. Diez sesiones de clase fueron diseñadas proporcionando la oportunidad a los estudiantes para seleccionar textos de acuerdo a criterios basados en el nivel de idioma de los estudiantes y de los intereses personales/profesionales. Los hallazgos son inherentes a tres categorías principales: la motivación, compromiso, contextualización e interpretación de lecturas. El objetivo principal de este proyecto era ver cómo los procesos de selección de textos de los alumnos guiados por criterios destinados y estrategias elaboradas influenciaban el aprendizaje y la adquisición en términos de motivación, percepción y opiniones hacia la lectura en inglés.

Palabras clave: autoselección, compromiso, hábitos de lectura, motivación, patrones de comportamiento, percepciones.

Introduction

Many researchers such as Bernhardt (1991), Gunning (2011), Kern (2000), Nelson (2008), Sprenger (2013), and Tankersley (2003) have agreed that reading is one of the most important skills that an individual should develop in order to succeed in academic and social pursuits. In Colombia and Latin America, this perception of the importance of the reading skills has been also adopted. Furthermore, Carrillo (2007); Lopera Medina (2012); Mahecha, Urrego, and Lozano (2011); and Shaw and McMillion (2011) have shown a huge interest in this topic and found that the lack of literacy practices in Latin America represents a huge drawback in language learners’ comprehension and interpretation skills. Their general findings regarding this phenomena can be summarized in these three main points: first, students do not comprehend what is given to be read during their courses of instruction; second, they do not feel motivated to read in the language; third, the failure in the achievement of the last two points results in the students’ frustration and negative opinions towards the reading practices in English as a foreign language (EFL) learning.

The main point of this research was to observe how including students in the text selection process for reading activities made it possible to actively involve them in their own learning processes as well as raise awareness about the importance of reading in EFL class. The researchers intend to contribute to the understanding and practice of adult education in Colombia in three different ways.

First, this study intends to open a dialogue about literacy practices, above all, in reading. Taking into account a student’s background should be expected to change the manner in which the student approaches literacy-building in a target language.

Second, this study intends to promote reading as a significant part of EFL instruction. Presently, this important practice is frequently set aside. This study intends to demonstrate how the practice of self-selection of texts makes reading more appealing and accessible to students and instructors.

Third, this study intends to show how, through adoption of the proposed principles, students can increase their comprehension, motivation, and reading habits—patterns of behavior that students do not presently demonstrate due to their discomfort as regards reading non self-selected materials in the EFL.

An objective was set at the beginning of this research project to observe how reading strategies and self-selection worked to change students’ negative perceptions of reading as well as how such reading strategies and self-selection could be used to promote engagement and motivation to enrich the literacy-building experience. In order to achieve the stated objective, the following question guided our research: What do reading selection principles reveal about EFL adult learners’ literacy practices?

Literature Review

Numerous researchers have been interested in the creation of ideal literacy environments in which students can develop high-quality reading and writing processes. Such research has often explored motivation strategies, comfort, and the achievement of durable results in language development (Lesgold & Welch-Ross, 2012; Mace, 1992; Walker, 2003). In the following paragraphs, we describe and discuss the theory underlying literacy, reading selection, reading strategies and comprehension as well as reading engagement and motivation.

This research highlights the importance of the self-selection principle as the main tool to achieve an ideal literacy environment in which an individual can develop all of his or her reading potential and show ways in which reading strategies were used to turn the “selected content” into meaningful learning experiences.

Hauser, Edley, Koening, and Elliott (2005) pointed out the importance of making literacy practices quotidian by highlighting all the great contributions that those practices make to an individual’s academic and social development.

Language Literacy

Mace (1992) stated that individuals get involved in adult literacy education for two major reasons: first, they need to develop literacy skills because their occupations demand it; second, because they may have or develop a desire to improve their literacy skills for personal growth reasons. However, there are some gaps in this dualistic approach and some researchers have taken the concept further. Kern (2000) for instance elucidates a new but broader view with his idea of multiple literacy, in which literacy is a series of “dynamic, culturally and historical situated practices of using and interpreting diverse written and spoken texts to fulfill particular social purposes” (p. 6). This definition helps us to have a clear and holistic view of what literacy really is, and how it goes beyond the ability to read. To explore these diverse and particular aspects, Kern identifies seven principles of literacy:

- Interpretation: A sense of operation between readers and writers of a text by which writers make constructions taking into account their thoughts, beliefs, and experiences and readers make their own deductions about the writer’s ideas and the text.

- Collaboration: The reader contributes to the creation of meaning when engaging with a written text; the writer always needs readers and writes taking into account a pre-determined audience. This joint participation in the act of constructing meaning is, in a very real sense, collaboration.

- Conventions: The culturally charged words and styles that influence the writer’s ideas and the reader’s understanding.

- Cultural knowledge: A vital feature that makes the creation of meaning possible. A writer and reader need common awareness of culture in order to make both reading and writing meaningful and to avoid misunderstandings.

- Problem-solving: A less obvious aspect of literacy. As Kern (2000) explains: “Because words are always embedded in linguistic and situational contexts, reading and writing involve figuring out relationships between words, between large units of meaning, and between texts and real or imagined worlds” (p. 17). Put differently, understanding the ways in which everything from the individual words to the structure of the work interrelates is a continuous act of problem solving.

- Reflection/self-reflection: This implies that reader and writer are constantly engaged in a process of interpreting and wondering about the speech and the humanity portrayed in a text.

- Language use: In Kern’s (2000) view, literacy is not just about reading and writing but also about the different contexts and situations in which communication occurs.

As might be evident to a discerning reader, these literacy principles are not unique to written language, but instead apply to language in all its domains. Kern (2000) puts it more succinctly: “Literacy involves communication” (p. 17).

Reading Selection

In order to make a text more comprehensible, it is necessary to offer readings that take into account readers’ preferences, contexts, and individual needs. Throughout this highly personalized approach, students can approach the readings with more confidence which will help them to achieve comprehension goals and to enjoy what they read.

Collie and Slater (2004) proposed that literature be a more emphasized part of language teaching programs and that it be used to further the learner’s mastery in the four skills: listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Such content can be used to provide two types of enrichment: first, cultural enrichment which increases insight into the culture whose language is being learnt; and second, language enrichment through the reading of substantial and contextualized bodies of text by which students may gain familiarity with many features of the written language.

But what sort of literature is appropriate to use with language learners? To answer this question, it is important to take into account that each group of students is unique and has particular needs, interests, cultural backgrounds, and language levels. It is important, therefore, to choose texts that are relevant to the life experiences, emotions, and/or dreams of the learners. According to Nuttall (1996), selecting texts involves three important components: suitability of content, exploitability, and readability.

First, through choosing suitable texts, a teacher helps students to develop reading skills more easily, especially when subject matter or content attracts students to read outside the class. This scaffolds success in classwork because through the utilization of texts that are appealing to students (rather than texts that bore them), the process of language learning interests and delights the readers.

Second, exploitability means that a student will draw upon useful language for real life situations from a text. A teacher materially assists the development of EFL competence by providing text options that stimulate production of useful language.

Third, texts should show readability which means that the teacher must assess a text for its level and range of vocabulary, unfamiliar or idiomatic usages, and other factors that may decide what portion of the text, if any, is appropriate for his or her students.

On the other hand, Mackey and Johnston (1996) proposed 14 factors that motivate students to continue the foreign language reading process. These are, in descending order of effectiveness: (1) following an author; (2) browsing or talking to a friend; (3) following a genre; (4) seeing a book cover; (5) starting one book in a series; (6) seeing someone else reading; (7) following a topic; (8) talking with a teacher or librarian; (9) doing a novel study; (10) receiving a book as a present; (11) using a book club list; (12) working on a school-subject thematic unit, such as mythology, poetry, or mystery; (13) finding a text appealing; and, finally, (14) forced reading.

Reading Strategies and Comprehension

In order to comprehend a text, each individual needs to utilize strategies to approach reading. In the last few decades, reading and literacy education has been a topic of great interest to many scholars in the United States and in Colombia whose studies have been focused on enhancing EFL learners’ reading comprehension (Koenig, 2010; Lopera Medina, 2012; Moreillon, 2007; Snow, 2002).

One thing that makes comprehension vary from one learner to the next is the content of the text itself. As Walker (2003) stated, readers’ levels of understanding differ “because readers’ knowledge of various topics differs” (p. 10). According to Walker, not achieving meaning while reading is not always related to a lack of reasoning capacity in the reader, but may have to do with other factors such as the strategies or background information they possess, the reading format, and their own personal goals (i.e., why they are reading). For instance, the meaning derived from a text by a student reading for pleasure may differ from the meaning derived from the same text when it is read as a school assignment.

Walker (2003) stated that in order to construct meaning, readers must be involved in a process that includes three strategies: first, predicting when a reader tries to infer meaning supported by his or her pre-existing knowledge of a subject, structure, or theme; second, comparing the subject matter presented by a text to the assumptions (predictions) made by the reader. Of these two steps, Walker says, “this internal dialogue enables readers to monitor their understanding” (p. 11). Third, elaborating, or making connections that link readers’ predictions to the actual text and thereby arriving at comprehension.

Reading Engagement and Motivation

Most works and studies addressing literacy in first and foreign languages cite engagement and motivation as key components for success. According to Lesgold and Welch-Ross (2012), “developing readers need to confront texts that are challenging, meaningful, and engaging” (p. 4). What is important to stress here is that texts must foster engagement.

McLaughlin (2012) highlights engagement as one of the principles underlying a successful reading experience. When the students have the opportunity to guide their own learning pace and have their own needs and expectations taken into account, they can access and achieve comprehension more easily. Guthrie and Wigfield (as cited in McLaughlin, 2012), observe that “engaged leaners achieve because they want to understand, they possess intrinsic motivations for interacting with text, they use cognitive skills to understand, and they share knowledge by talking with teachers and peers” (p. 19).

With respect to motivation, McLaughlin (2012) asserts that because the majority of adult students carry on busy lives, teaching adults requires learning environments that promote motivation in order to have students persist in using literacy practices. Education that develops motivation and engagement with reading pays significant dividends for adult students’ personal growth in areas such as autonomy, literacy awareness, interpersonal skills, and not least, access to new knowledge.

Adult literacy requires several key components, of which McLaughlin (2012) identifies one: purpose or motivation, as fundamental. If this component is present in sufficient quantity, a language learner will achieve significant results.

Method

This project demonstrates how through the implementation of the self-selection principle alongside reading strategies during ten class sessions of adult literacy education, it was possible to foster incremental growth in language and create a comfortable literacy environment where students could develop their literacy potential as was demonstrated through perdurable, practical, and meaningful learning.

The main objective of this qualitative research was the interpretation of students’ behavior. This study provided the opportunity to observe the implementation of reading self-selection and reading strategies, to collect data, and to qualitatively analyze outcomes. This project followed the Action Research (or AR) model expounded on by Burns (2010) which is comprised of four steps: planning, action, observation, and reflection. Burns states:

AR involves taking a self-reflective, critical, and systematical approach to exploring your own teaching context. By critical I don’t mean being negative and derogative about the way you teach, but taking a question and problematizing stance toward your teaching. My term problematizing, doesn’t imply looking at your teaching as if it is ineffective and full of problems. Rather, it means taking an area you feel could be done better, subjecting it to questioning and then developing new ideas on alternatives. (p. 2)

The purpose of Burns’s AR aligned with the research objective which was the improvement of teaching practices and classroom dynamics through critical reflection on a teaching practice (assigned reading), problematizing this practice and generating new alternatives to create more meaningful and perdurable learning.

In the present case the reading self-selection is proposed as a pedagogical strategy consisting of two stages which were designed and implemented. The first stage consisted of a set of questions prior to the reading task with the objective of preparing the learner for the task to come. Likewise the second stage encompasses a set of questions this time aiming at checking the student’s comprehension always in concordance with the main research question “What do reading selection principles tell us about the literacy practices of EFL adult students?”

To such end ten reading lesson were designed. In order to create an effective and coherent plan given this time constraint, the research team had to carefully consider the students’ profiles, reading proficiency, interests, and professional and personal goals. In working with a learning institution, it was also necessary to take into account institutional resources, philosophy, and willingness to support this project.

The research took place in a small, private language institution in Bogotá, Colombia. The school was chosen for its approach to discourse development, the characteristics of its population (adult learners), and the resources and support available to meet the needs of the project. In concert with this institution, the research team taught a pilot lesson in order to discover the perspectives and reactions of the population towards the project, and whether or not the students would be receptive to the implementation of this research.

The first “action step” activity, planning, was carried out prior to a pilot class with five adult students. The institution allowed one hour to present our methods in this pilot class and the students consisted of two female doctors, one female lawyer, a business administration student, and a female financial advisor. All of them were between the ages of 20 and 40 years old. The pilot class started with an introductory activity (see Appendix A). During this time, the project, the purposes for it, the expectations of students, and their role in the research, were all explained to the students.

Several reading options which took into account the students’ personal contexts were prepared by researchers before this class. From this first pilot class, students were given the opportunity to exercise reading selection from among these texts. Each student chose an article that they preferred and carried out assigned activities with it. These helped to introduce vocabulary, and then, based on the strategies for reading, some before reading questions were given to assess students’ background knowledge. At the end, post-reading questions about student’s perspectives, opinions, and understanding of the articles they had read were asked. Having read the articles, the students answered a survey which contained questions about their perspectives towards reading (see Appendix B). The survey collected data which were used to guide the selection and preparation of material to be used in future sessions.

The next step was the action step of carrying out the proposed experimental practices and changing the classroom approach to assigned reading. Thanks to students’ positive perceptions of our work, the institution allowed us to implement our research project with all of the resources that we needed. We were given one hour each Friday from 6:30 to 7:30 a.m. for 10 weeks within one semester.

For the third step, observation, data were collected using different instruments: journals, video recordings, and photographs. According to Burns (2010), these methods allow teachers to explore the realities of practical circumstances easily without the need to have a control group.

Finally, in reflection, all of the gathered information for this research was transcribed in order to make it easier to organize and analyze. All information with any relationship to the research questions was organized into “survey data” and “article answer data.” Surveys were organized based upon the date the survey was administered, and article responses were organized depending on the topic of the chosen reading. All of the data were given a code. In order to protect the participants’ identities, participants were identified with the letter P followed by a number and the source from which data were taken (e.g., P1, survey).

Data Analysis

The data gathered for analysis in this project included behavioral patterns, changes in the students’ perceptions, and outcomes generated after carrying out ten sessions where the self-selection principle and the strategies of reading were implemented. Outcomes were measured, and then classified. As soon as this information was organized, analysis began and three patterns emerged from this data, each comprising a category for analysis. These three categories are:

- Self-Selection and Strategies for Reading

- Engaging Students to Read Through Restructuring of Teaching Dynamics

- Reinforcement of Habits in EFL Reading Practice

Self-Selection and Strategies for Reading

This category includes how the strategies of reading and self-selection influenced the development of reading comprehension and interpretation skills. Evidence gathered revealed students’ reactions, outcomes, and changes in behavior.

Two important changes to the EFL learning were clearly observed during this project: the improvement of students’ productions skills (speaking and writing), and the improvement of their comprehension skills, as will be demonstrated along this section.

According to one student, this experience was an opportunity to learn English in a more productive way. However other students, parti-cularly those whose main purpose was to learn the language for academic or professional objectives, showed different interests which focused more on comprehension and interpretation. It was possible to perceive and measure these attitudes from the very first survey.

What are your expectations about this course?

P1: I have more expectations, I need learn write, read, interpretate articles, it’s very important for me. [sic]

The self-selection principle allowed students to choose readings relevant to their careers, to prepare themselves for written content that they may face in the future. Students were so motivated to participate by this approach that the teacher did not have to impose assignments, but rather, the student asked for more activities.

Giving students the freedom to select what they wanted to read seemed to promote student learning and engagement. Students found the content not just useful for their EFL learning; they also found it useful for their academic and professional lives. Consider the following statement by a student:

What is the thing you like the most [from the project]?

P2: I like ‘cause I can learn something from real life. [sic] (Survey)

In this answer, the student expressed a positive outlook about the reading of something that could be useful and relevant to his interests, likes, and context. By reading this kind of material, the students felt motivated to continue reading in the EFL. This suggests that as long as students find the material relevant to their personal needs, they will be willing to read.

Strategies for reading played an important role in the EFL classroom. The self-selection of readings particularly improved students’ comprehension and aided in the contextualization of contents. The first strategy applied in the self-selection of readings served the purpose of contextualizing the students. In the text is a set of pre-reading questions, which allowed the assessment of prior knowledge of a subject in order to make the content more relevant to them. The second strategy, the post-reading questions, helped students to develop deeper answers, points of view and conclusions as shown below:

What do you think about this article?

P5: I think is a good way to know the information the test driver on young people how change the percent in the last years.

Do you think that this may happen in Colombia?

P5: I don’t think that this in Colombia, I mean about fuel prices is so expensive but is impossible that someone give you a premium. [sic] (Survey)

The first question checked what they understood about the reading by encouraging them to share their opinion. The second question required the students to contextualize the topic of the reading into their own reality by asking about the current national situation regarding the issue and asking the students to compare it with the article. The second question also asked the students to access background knowledge and to draw a conclusion based on understanding and contextualization of the issue. These kinds of questions required a high level of comprehension: It was not easy to translate certain phenomena from another country into their own—students were required to go beyond simple answers or opinions. In the answer shown above, the student responded that the phenomenon may not occur in Colombia because of issues that went beyond the scope of the article, for example the “fuel prices” in Colombia. This demonstrates the students’ ability to contextualize the new information and stretch their language to express their new knowledge.

Engaging Students to Read Through Restructuring of Teaching Dynamics

This category deals with the motivational factors and interest in learning that reading selection brought about in the school life of students. It focuses on how, through the self-selection of readings, students became motivated in the language learning process.

Three important factors had to be taken into account when we were creating motivation-stimulating activities: (1) keeping the reading selection principle in all of the lessons, (2) creating interesting activities based on the readings, and (3) adapting the readings to the students’ preferences with meaningful content. From the first class onward, everything was structured in order to integrate the opinions, interests, and backgrounds of the students into the design of the lessons. Hard work in this regard produced important outcomes in student engagement and achievement.

Knowing the readers’ preferences in advance allowed researchers to prepare and adapt the readings offered, the questions asked, and the activities planned. This made it possible to make the content more accessible to students and give them real ownership of what they learned. In order to discover these readers’ preferences, it was necessary to ask some questions beforehand. An example is as follows:

What kind of literary genre do you read the most?

P1: Family, children and God.

P2: I like to read about horror. [sic] (Survey)

By taking students’ preferences into consideration, certain targeted materials were provided to those students; this strategy may work to encourage the students’ literacy development, the learning of certain vocabulary, or the practice of EFL learning. In the case of these students: religion, family, and horror, respectively, were genres relevant to their interests. If any readings related to these topics or preferences could be provided, the students would certainly be more interested in reading them. This is the main function of strategies for reading: to guide students and make required readings more comfortable for them. As long as they feel comfortable with what they read and as long as they feel that the content is useful, they will be engaged with the literacy practices and will take every advantage from reading in the EFL.

When students realized the advantages that EFL literacy practices bring to their lives, they demonstrated willingness to continue with these practices, even to the point of developing reading habits. The following conversation demonstrates student perceptions and feelings towards reading practices after the intervention:

How do you feel about reading in English?

P2: Yes, I like in English, because is very important for my profession.

P6: I like read in English too but I need to learn perfect and I can understand all the context. [sic] (Survey)

The greatest motivating factors for learning the EFL for these participants were professional and academic considerations. As evidenced, when the students found that what they read was important for their lives, their perceptions towards reading in EFL changed.

In the middle of the project, a second survey was implemented with the purpose of collecting feedback about how the students were reacting to the readings, articles, and activities so far. This survey made it possible to see that students were still highly motivated. It was also possible to see that the grammatical structures of their answers had improved in comparison to the answers they provided during the first survey. Students used better vocabulary to express their opinions towards the project:

What are your opinions about the project so far?

P4: I like it a lot, we feel very funny. All the time we’re thinking and talking in English.

P6: I think is a good project, where you can learn vocabulary and a good way to learn. [sic] (Survey)

The use of the EFL all the time during the im- plementations, the preparation of quality activities, and the sharing of control over choice of learning material were the main reasons for students’ ongoing high levels of motivation and improvement in their production and use of grammatical structures in English. Observe the correct usage of the object pronoun “it” used in the former answer (a structure not present in the student’s first survey), the correct conjugation of the verb “to be,” the good use of the relative pronoun “where” and the proper conjugation after the modal verb “can” in the latter answer.

As a general conclusion we can say that students need to be motivated in order to develop their full potential in any pursuit—including language learning. As long as the students feel comfortable with the content and they feel it is useful for their own lives, they will be willing to read, and to generate the habits that will support sustained reading practice.

Reinforcement of Habits in EFL Reading Practice

This category deals with how self-selection contributes to generate engagement in the reading practices and how it creates and reinforces reading habits in EFL instruction. Failure in foreign languages reading—especially independent reading—is likely when the text cannot convey its meaning to a reader. This most often occurs when the text is extremely long or the content itself is not appealing to the reader. This is when the self-selection principle may contribute to improving reader success by turning this negative situation into a positive one.

One of the main factors determining text selection was participants’ academic background knowledge: for example, doctors tended to read about medicine and health; administration professionals preferred to read business topics, and so on; however, it was evidenced by our group that when students had a variety of texts available, they also read in fields different from their own.

What books do you read?

P7: Leadership. (Survey)

Thanks to the strategies for reading it was possible to use the students’ interest to introduce the EFL learning. As long as the students felt that what was being read was useful to what they needed, they demonstrated willingness to continue reading on their own. This gave students the opportunity to achieve goals and overcome professional barriers to use EFL. However, other aspects beyond professional considerations motivated students as well:

What books do you read?

P3: Books relations with the family, children. [sic] (Survey)

On the other hand, students demonstrated an increasing desire to read in English in diverse topics and fields as the semester progressed. In fact, students asked for new materials in categories beyond those proposed at the beginning of the project. Their confidence was increased and this allowed them to explore totally new areas. This may be the most significant discovery of this research project.

What kind of readings would you like to read in the next sessions?

P8: I would like to read about traveling and news in general of the current times.

P10: I would like read about history, politics movies, action, stories of the bible, culture different countries and business. [sic] (Survey)

As it is possible to observe from answers to the survey taken in the middle of this project, students demonstrated confidence and self-efficacy. When the students developed more confidence and comprehension in just one subject in EFL, alternative genres and contents became easier to approach.

Through the simple implementation of two principles: strategies of reading and the self-selection principle, it was possible to engage students in reading and instill them with good reading habits in EFL. This achieved McLaughlin’s (2012) ideal: turning learners into “good readers” who read well across different genres or subject areas.

This result can be duplicated across content areas, and in different contexts, with a basic restructuring of teaching dynamics. The lesson for educators is this: In order to create more productive and meaningful learning experiences inside the classroom, and generate lasting improvements in student achieve- ment, get to know your students and let that knowledge guide lesson design.

Conclusions

The restructuring of teaching dynamics using the reading selection principle as a pedagogical strategy yields positive outcomes in terms of motivation and engagement; and the strategies for reading were key components for improving the participants’ understanding of the different texts they chose contributing to the students’ EFL learning experience in many other ways.

It was found that by allowing students to choose their own readings (self-selection principle) their learning experiences became more comprehensive and richer. Furthermore, it was also observed that the manner in which the texts were adapted and prepared allowed the students to have a more meaningful learning experience. Formulating questions before the reading task contribute to contextualize the content to the reader and prepare the learner for the task at hand. The questions after the reading allowed the teacher to check the students for understanding and allowed students to draw connections to the realities.

By using these strategies at the beginning of all of the class sessions, teachers were able to gain a better understanding of the students’ interests, which were then used to guide lesson design. Pre-lesson questions prepared students to contextualize the readings and prepare themselves for the ensuing reading. Additionally, students’ reading comprehension increased as a result of this initial preparation, which led to meaningful learning and an increased ability to express, in English, relevant, contextually-appropriate opinions on the topics discussed within the readings.

In summary, the self-selection principle and the reading strategies were the main focus of this research project, and the basis of the EFL learning process in these 10 class sessions that gave students the freedom to choose what they wanted to read.

This study examined a student-centered pedagogical strategy that allowed students to take control of their learning and to become engaged and motivated in just 10 weeks. This demonstrates that through the self-selection principle and reading strategies students have the potential to overcome their negative perceptions towards reading, their lack of reading habits, and especially, their fears of reading in EFL.

We hope the lessons learned from this study might serve as a replicable model to support the importance of integrating the self-selection principle and strategies of reading in order to restructure the EFL teaching dynamics in Colombia, as well as anywhere else, so as to improve motivation, engagement, and positive opinions towards reading.

*This article is a partial report of a group research project conducted in 2014 as a requirement to graduate from the Bilingual Education Teaching Credential Program at Universidad El Bosque. The research was hosted by the English institute Wall Street English in Bogota and the co-researchers for the project were Cristian Esteban Mejia and Jonny Rodriguez Ramirez. However, they had no participation in the writing of this article.

References

Bernhardt, E. B. (1991). Reading development in a second language: Theoretical, empirical, and classroom perspectives. Norwood, MA: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Burns, A. (2010). Doing action research in English language teaching: A guide for practitioners. New York, NY: Routledge.

Carrillo, G. (2007). Realidad y simulación de la lectura universitaria: el caso de la UAEM [Reading and simulation of university-level reading: The UAEM case]. Educere, 11(36), 97-102.

Collie, J., & Slater, S. (2004). Literature in the language classroom: A resource book of ideas and activities (8th ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Gunning, T. G. (2011). Reading success for all students: Using formative assessment to guide instruction and intervention. Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass.

Hauser, R. M., Edley, C. F., Koening J. A., & Elliott, S. W. (Eds.). (2005). Measuring literacy: Performance levels for adults. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kern, R. (2000). Literacy and language teaching. Oxford, UK: Oxford University.

Koenig, R. (2010). Learning for keeps: Teaching the strategies essential for creating independent learners. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development (ASCD).

Lesgold, A. M., & Welch-Ross, M. (Eds.). (2012). Improving adult literacy instruction: Developing reading and writing. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Lopera Medina, S. (2012). Effects of strategy instruction in an EFL reading comprehension course: A case study. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 14(1), 79-89.

Mace, J. (1992). Talking about literacy: Principles and practices of adult literacy education. Florence, KY: Routledge.

Mackey, M., & Johnston, I. (1996). The book resisters: Ways of approaching reluctant teenage readers. School Libraries Worldwide, 2(1), 25-38.

Mahecha, R., Urrego, S., & Lozano, E. (2011). Improving eleventh graders’ reading comprehension through text coding and double entry organizer reading strategies. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 13(2), 181-199.

McLaughlin, M. (2012). Guided comprehension for English learners. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Moreillon, J. (2007). Collaborative strategies for teaching reading comprehension: Maximizing your impact. Chicago, IL: ALA Editions.

Nelson, T. (2008). Predictive factors in student gains in reading comprehension using a reading intervention program (Doctoral dissertation). University of South Dakota, USA.

Nuttall, C. (1996). Teaching reading skills in a foreign language (1st ed.). London, UK: Macmillan.

Shaw, P., & McMillion, A. (2011). Components of success in academic reading tasks for Swedish students. Ibérica, 22, 141-162. Retrieved from http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=287023888008.

Snow, C. E. (2002). Reading for understanding: Toward a research and development program in reading comprehension. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Sprenger, M. (2013). Wiring the brain for reading: Brain-based strategies for teaching literacy. Somerset, NJ: Wiley.

Tankersley, K. (2003). The threads of reading: Strategies for literacy development. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development (ASCD).

Walker, B. J. (2003). Supporting struggling readers. Scarborough, CA: Pippin Publishing Corporation.

About the Author

Juan Sebastián Basallo Gómez holds a B.Ed. in bilingual education with a special emphasis on teaching the English language. Currently he is working as the head of the languages area in Colegio Fontan (Colombia). His professional interests are in British literature and creative writing.

Acknowledgements

It is important to mention the continuous support of our thesis advisor Wilder Escobar who helped us during the presentation of this work as a graduation requirement. Then convinced, advised, and helped me along the publication process of this article.

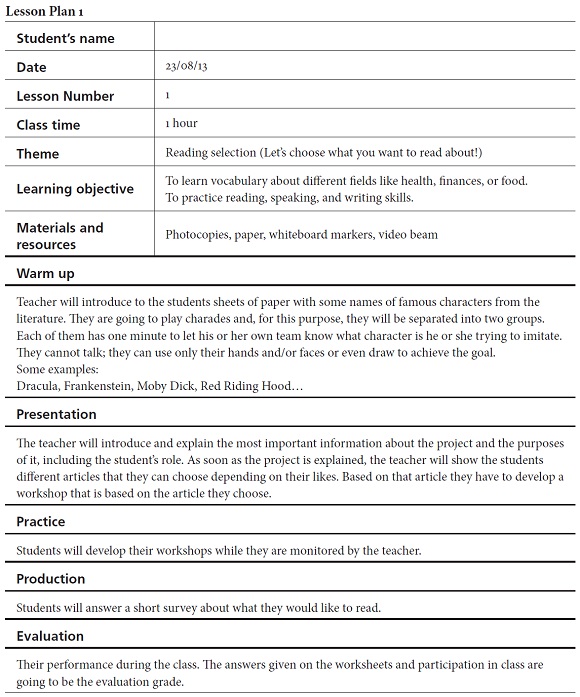

Appendix A: Example of a Lesson Plan

What do reading selection principles tell us about the literacy practices of EFL adult students?

Names:

Questionnaire

Do you read?

What books do you read?

When do you read?

Do you read in English?

What books do you read in English?

When do you read in English?

Do you like to read in your free time?

What kind of literary genre do you read the most?

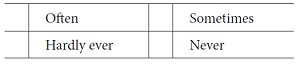

How often do you read in English outside the classroom?

Which skill do you find the most difficult in class?

Which medium do you like to read with (books, Internet)? Why?

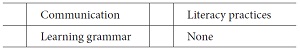

In your language classes, which of the following aspects are given more attention?

How do you feel reading in Spanish?

How do you feel reading in English?

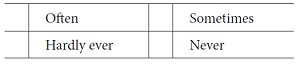

How often do you visit libraries?

Do you have literary books (English) at home? Which ones?

When do you think good reading skills in a foreign language will help you the most?

What are your expectations about this course?

References

Bernhardt, E. B. (1991). Reading development in a second language: Theoretical, empirical, and classroom perspectives. Norwood, MA: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Burns, A. (2010). Doing action research in English language teaching: A guide for practitioners. New York, NY: Routledge.

Carrillo, G. (2007). Realidad y simulación de la lectura universitaria: el caso de la UAEM [Reading and simulation of university-level reading: The UAEM case]. Educere, 11(36), 97-102.

Collie, J., & Slater, S. (2004). Literature in the language classroom: A resource book of ideas and activities (8th ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Gunning, T. G. (2011). Reading success for all students: Using formative assessment to guide instruction and intervention. Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass.

Hauser, R. M., Edley, C. F., Koening J. A., & Elliott, S. W. (Eds.). (2005). Measuring literacy: Performance levels for adults. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kern, R. (2000). Literacy and language teaching. Oxford, UK: Oxford University.

Koenig, R. (2010). Learning for keeps: Teaching the strategies essential for creating independent learners. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development (ASCD).

Lesgold, A. M., & Welch-Ross, M. (Eds.). (2012). Improving adult literacy instruction: Developing reading and writing. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Lopera Medina, S. (2012). Effects of strategy instruction in an EFL reading comprehension course: A case study. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 14(1), 79-89.

Mace, J. (1992). Talking about literacy: Principles and practices of adult literacy education. Florence, KY: Routledge.

Mackey, M., & Johnston, I. (1996). The book resisters: Ways of approaching reluctant teenage readers. School Libraries Worldwide, 2(1), 25-38.

Mahecha, R., Urrego, S., & Lozano, E. (2011). Improving eleventh graders’ reading comprehension through text coding and double entry organizer reading strategies. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 13(2), 181-199.

McLaughlin, M. (2012). Guided comprehension for English learners. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Moreillon, J. (2007). Collaborative strategies for teaching reading comprehension: Maximizing your impact. Chicago, IL: ALA Editions.

Nelson, T. (2008). Predictive factors in student gains in reading comprehension using a reading intervention program (Doctoral dissertation). University of South Dakota, USA.

Nuttall, C. (1996). Teaching reading skills in a foreign language (1st ed.). London, UK: Macmillan.

Shaw, P., & McMillion, A. (2011). Components of success in academic reading tasks for Swedish students. Ibérica, 22, 141-162. Retrieved from http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=287023888008.

Snow, C. E. (2002). Reading for understanding: Toward a research and development program in reading comprehension. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Sprenger, M. (2013). Wiring the brain for reading: Brain-based strategies for teaching literacy. Somerset, NJ: Wiley.

Tankersley, K. (2003). The threads of reading: Strategies for literacy development. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development (ASCD).

Walker, B. J. (2003). Supporting struggling readers. Scarborough, CA: Pippin Publishing Corporation.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Tatiana Becerra Posada. (2024). Potential of a Pluriversal Literacies Framework for Decolonizing English as Foreign Language (EFL) Policy and Practice in Colombia. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 26(1), p.24. https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.20531.

2. F Reffiane, R S Iswari, P Marwoto. (2019). The effectiveness of Lectora Inspire media assisted guided inquiry method on the students’ critical thinking skill in the science nature: a case study at gugus Diponegoro elementary schools Semarang. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1170, p.012078. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1170/1/012078.

3. Tania Tagle Ochoa, Cecilia Schuster Muñoz, Viviana Rojas Caro, Mónica Campos Espinoza, Lucia Ubilla Rosales, Luzmila Flores Gajardo, Mark Briesmaster. (2020). Enseñar y aprender a leer en inglés: creencias de futuros docentes de lengua extranjera chilenos. Folios, (52), p.187. https://doi.org/10.17227/folios.52-11778.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.