Published

An Eclectic Professional Development Proposal for English Language Teachers

Una propuesta ecléctica de formación docente para profesores de inglés

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n1.49946Keywords:

English teachers’ profile, professional development, teacher quality (en)calidad de los profesores, desarrollo profesional, perfil de docentes de inglés (es)

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n1.49946

An Eclectic Professional Development Proposal for English Language Teachers

Una propuesta ecléctica de formación docente para profesores de inglés

Orlando Chaves*

Maria Eugenia Guapacha**

Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia

*orlando.chavez@correounivalle.edu.co

**maria.guapacha@correounivalle.edu.co

This article was received on April 1, 2015, and accepted on July 28, 2015.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Chaves, O., & Guapacha, M. E. (2016). An eclectic professional development proposal for English language teachers. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 18(1), 71-96. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n1.49946.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This article reports a mixed-method research project aimed at improving the practices of public sector English teachers in Cali (Colombia) through a professional development program. At the diagnostic stage surveys, documentary analysis, and a focus group yielded the teachers’ profile and professional needs. The action phase measured the program’s impact via surveys, evaluation formats, a focus group, researchers’ journal, and documentary analysis. Findings revealed that an eclectic approach tailored to the participants’ needs and interests and a practice-reflection-theory cycle improved the teachers’ quality.

Key words: English teachers’ profile, professional development, teacher quality.

Este artículo versa sobre una investigación mixta que buscaba mejorar la enseñanza de un grupo de profesores de inglés del sector público en Cali (Colombia) a través de un programa de desarrollo profesional. En el diagnóstico, encuestas, análisis documental y un grupo focal arrojaron el perfil y las necesidades profesionales de los docentes. La implementación evaluó el impacto del programa a través de encuestas, formatos de evaluación, grupo focal, diario de investigación y análisis documental. Los resultados revelaron que un enfoque ecléctico ajustado a las necesidades e intereses de los participantes y un ciclo de práctica-reflexión-teoría fortalecieron la calidad de los profesores.

Palabras clave: calidad de los profesores, desarrollo profesional, perfil de docentes de inglés.

Introduction

Recent language education policies in Colombia have ignited interest about the English teacher quality. Although policies are necessary to support coordinated teachers’ professional development actions, studies about teachers’ needs and quality are still scarce in our scholastic milieu and most of them refer to primary schools (Bastidas & Muñoz Ibarra, 2011; Cadavid Múnera, McNulty, & Quinchía Ortiz, 2004; McNulty & Quinchía Ortiz, 2007) or are based on only language test results (Sánchez Jabba, 2013). This article reports a quantitative-qualitative (QUAN-QUAL) sequential explanatory study about the impact of a professional development program (PDP) for English teachers in public schools in Cali, Colombia. The diagnostic stage was a survey study that allowed identifying the teachers’ profile and professional needs on the bases of which a PDP was further designed, implemented, and evaluated in a qualitative action stage.

Literature Review

Teacher Quality

Teacher quality (TQ) is a common concern in daily life, education policies, and academic literature. The literature review about TQ in English teaching involves qualifications, experience, methodology/teaching practice, knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes. Some external factors are also linked to TQ like students’ attitudes, available resources, adequate time-on-task, class size, and teacher work assignment (Darling-Hammond & Bradsford, 2005; Hanushek & Rivkin, 2007; Johnson, 2006; Wright, 2012).

In education discourse, TQ often has different definitions. Kennedy (2008) points out that TQ has become a ubiquitous term without clear meaning and mentions five different connotations: (a) tested ability, test scores used as an indicator of TQ for recruitment; (b) credentials, in the form of licenses and certificates that prove knowledge and experience; (c) quality of classroom practices, referring to the work teachers do inside their classrooms; (d) teachers’ effectiveness in raising the level of student achievement; and (e) beliefs and values.

Likewise, there are three different but widespread terms associated with a quality teacher: good teacher, effective teacher, and highly qualified teacher (Paone, Whitcomb, Rose, & Reichardt, 2008). The first term is germane to daily school discourse and refers to teachers who “teach well.” However, the concept of good teacher is not limited to what he/she does in the classroom. The second term—teacher effectiveness—is common in education researchers and authorities referring to students’ achievement on tests resulting from teaching (Clotfelter, Ladd, & Vigdor, 2006; Coggshall, 2007; Darling-Hammond, 1999; Harris & Ó Duibhir, 2011; Rivkin, Hanushek, & Kain, 2005; Valentine, Rakes, & Canada, 2010). This is a very narrow conception of effectiveness (Kennedy, 2008) and there is still lack of agreement on how best to identify and measure effective teaching (Kane, Taylor, Tyler, & Wooten, 2011). This widespread view linking TQ to students’ and teachers’ results on language tests, especially in the public sector, is prominent in the current Colombian bilingualism policies (Cely, 2009; Sánchez Jabba, 2013). The third term—highly qualified teacher—is also usual in educational legislation and stakeholders’ discourse. This teacher “possesses the sophisticated content knowledge and familiarity with appropriate pedagogical and assessment strategies” (National Council of Teachers of English [NCTE], 2004, p. 1). In our scholastic system TQ is associated with qualifications.

According to the NCTE (2004), the teacher’s skills and expertise fall in the areas of pedagogical content knowledge, planning instruction, and skills and strategies to engage students. These skills are developed through time and are usually called experience. NCTE’s definition illustrates how TQ amalgamates the features quality teachers have or must have (skills, knowledge, expertise, and the like), the qualities of what they do or should do (e.g., assessment), and the results they obtain in their students.

A step ahead in the comprehension of TQ is given by Kunter et al. (2013) who propose the concept of professional competence as “the skills, knowledge, attitudes, and motivational variables that form the basis for mastery of specific situations” (p. 3). Locally, this notion has been studied by Kostina and Hernández (2007).

In general, TQ refers to the various teacher-related characteristics associated with positive educational results. Figure 1 summarizes the diverse perspectives of TQ. Nonetheless, it is necessary to keep in mind Kennedy’s (2008) assertion about this complex matter of TQ:

True understanding of teacher quality requires us to recognize that these many facets are distinct, not always overlapping, and not always related to one another. Moreover, we aren’t even sure how they influence and interact with one another when they do. (p. 60)

In this study, TQ components were summarized in four categories: qualifications, knowledge, practices (methodology), and image (personal traits and professional attitudes, values, and beliefs). TQ components were analyzed in depth in order to support a sound characterization of the teachers to whom the PDP was addressed. The bottom line was that professional development is a good means to assure TQ.

Professional Development of Language Teachers

Professional development (PD) on the whole is the development of a person in his/her professional role (Villegas-Reimers, 2003). According to Villegas-Reimers, the notion of PD is linked to two similar but narrower concepts: career development, as the maturity teachers attain through their professional career, and staff development, as the in-service programs aimed at promoting the growth of teachers.

For Richards and Farrell (2005), PD is one of the two views derived from two general objectives in teacher education: training and development. Training encompasses the initial or pre-teaching teacher education, in a BA program, for instance; development refers to the in-service and long-term development of teachers. For the authors, teacher training usually establishes short-term goals linked to the teachers’ present or immediate needs. Teacher training typically involves comprehending theory, and then applying it to teaching until skills in demonstrating the principles and practice are developed and observed. In turn, teacher development is designed for long-term periods whose goal is to facilitate teachers’ self-understanding and to include a reflective component as a basis of the program. PD improves the performance of teachers, students, and the school itself which Richards and Farrell consider a bottom-up process.

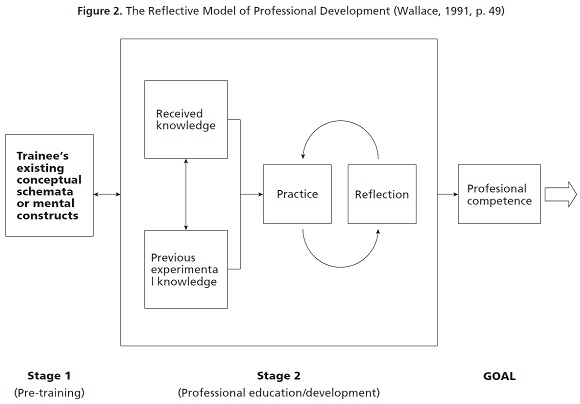

Furthermore, regarding the distinction between teacher training or education and teacher development, Edge (as cited in Wallace, 1991), asserts that: “the distinction is that training or education is something that can be presented or managed by others; whereas development is something that can be done only by and for oneself” (p. 3). Wallace (1991) discusses two previous models of professional education: craft and applied science, and proposes his own, reflective. The craft model is based on experiential PD; in it, expertise is demonstrated by a master practitioner and imitated or practiced by the young trainee. This imitative practice is supposed to lead to professional competence. Wallace criticized this model as simple, static, imitative, and disregarding the growth of relevant scientific knowledge. Schön’s (1987) applied science model analyzed teaching problems using scientific knowledge to achieve clear objectives, underscoring theory and seeing practice as instrumental. Wallace disapproved this model because it separates theory (research) and practice.

In opposition to those models, Wallace (1991) proposed the reflective model that balances both experience and scientific bases of teaching carrying out professional development through a combination of “received” and “experiential” knowledge; the first one includes the disciplinary theory that supports language, teaching, and learning, while the second one is related to the teachers’ ongoing experience and expertise. Figure 2 summarizes this model.

In general, PD has moved from an initial focus on training to modern views that include the teachers’ personal and professional dimensions, knowledge, experience, working conditions, and agendas (Cárdenas Beltrán & Nieto Cruz, 2010). The training perspective has been considered a “deficit model,” opposite to the second one, seen as a cooperative-process view (Richardson & Anders as cited in Cárdenas Beltrán & Nieto Cruz, 2010). The former aims at fixing teaching practice deemed outdated or somehow defective; it is focused on the academic knowledge to be transmitted by the teachers and its methodology seeks that the teachers apply in their settings the knowledge learned in the training courses. The cooperative-process perspective pursues the relationship between theory and practice, giving importance to reflection and building teachers’ analytical and critical awareness.

Specifically, teachers’ PD is “the professional growth a teacher achieves as a result of gaining increased experience and examining his or her teaching systematically” (Villegas-Reimers, 2003, p. 11), comprises formal (e.g., attendance of workshops) and informal experiences (e.g., reading professional publications), and it is necessary to consider the experiences, processes, and the contexts in which teachers’ PD takes place.

Recent trends in PD are based on constructivism rather than on transmission-oriented models (Villegas-Reimers, 2003). It means that, in PDPs, teachers are active learners. Likewise, for Darling-Hammond (1998) a PDP is related to the daily activities of teachers and learners and it should be based on schools.

To summarize, we consider that professional development of language teachers should involve permanent reflection, theory and practice, knowledge and skill, learning and re-learning, science and craft in any combination as proposed in the various abovementioned perspectives.

Method

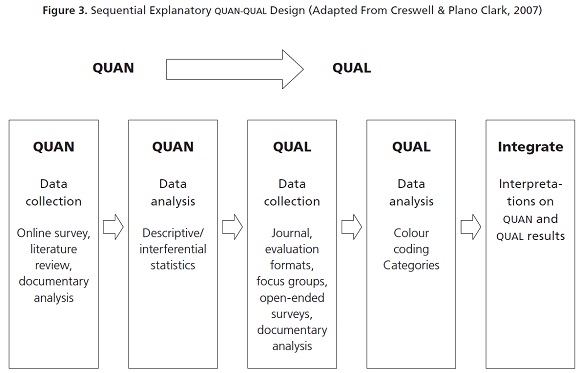

A mixed-method research design (Creswell, 2009) was adopted, specifically, a sequential explanatory QUAN-QUAL design (Creswell, 2012; Creswell & Plano Clark, 2007). In the diagnostic stage, a quantitative survey research (Creswell, 2012) led to an in-depth description of the English teachers in Cali in order to analyze and understand their background and present status. Free association exercise, literature review, focus group, and documentary analysis contributed to get the profile and professional needs of the subjects. In the action stage, a qualitative action-research (Carr & Kemmis, 1986; Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, 2007) was carried out to evaluate the impact of the PDP by means of a research journal, focus groups, evaluation formats, and documentary analysis. Thus, the following cycle was pursued:

(1) Planning: design of workshops tailored to the teachers’ needs (whole program: 150 hours). (2) Acting: a pilot PDP course of 45 hours (nine workshops, 5 hours each) was carried out; twelve teachers participated (see Appendix for a workshop sample). (3) Observing: recorded observations in researchers’ journals and format evaluations. (4) Reflecting: examination of positive aspects and aspects to improve upon. This cycle was repeated throughout the intervention. Figure 3 recapitulates the research design process.

Participants

Diagnostic stage: 63 out of 301 public sector English teachers in Cali, 57 students from eighth and eleventh grades, five parents, and nine school administrators belonging to a total of 40 out of 92 public schools in Cali. Action stage: 12 out of 30 public sector English teachers attended the PD pilot program.

Data Collection and Instruments

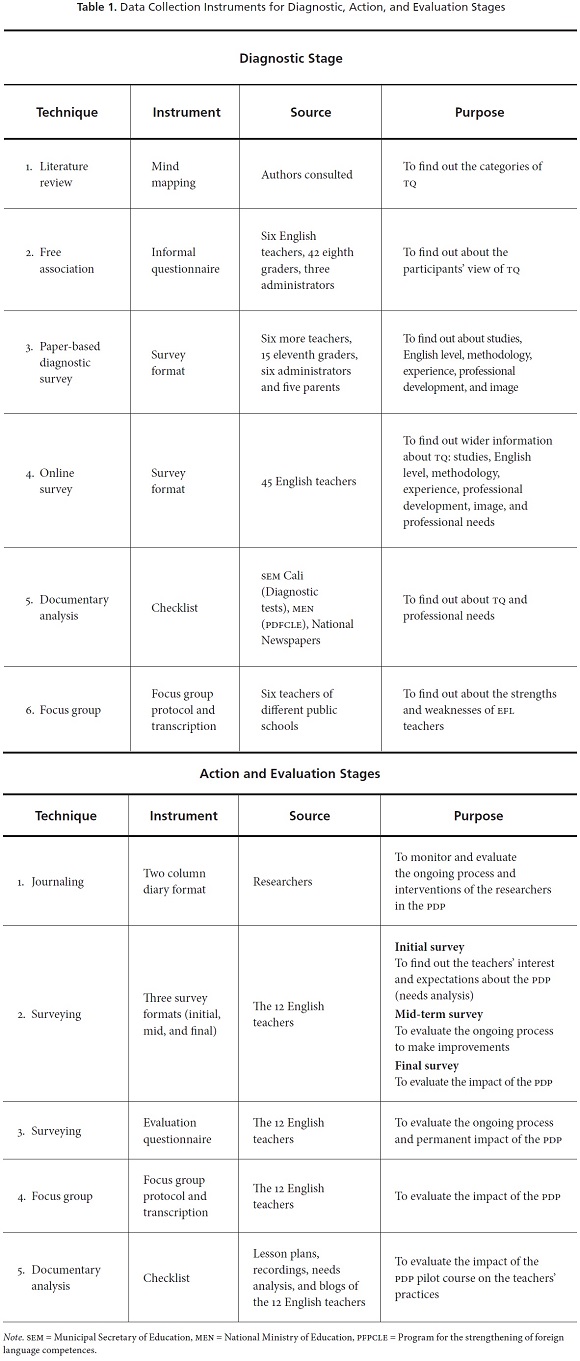

Table 1 shows the instruments used to collect data in diagnostic, action, and evaluation stages.

Findings

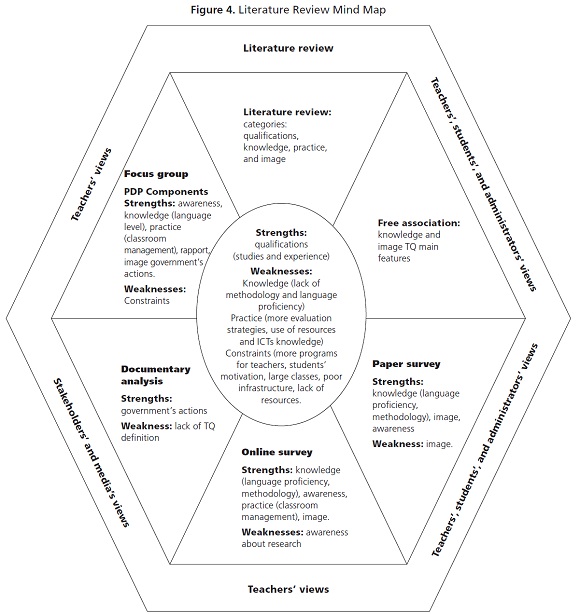

Four main categories were derived from the research questions: (1) Teachers’ Main Quality Features, (2) Teachers’ Professional Needs, (3) PDP Components, and (4) Impact of PDP on Teachers’ Practices. The diagnostic stage addressed the first three categories, while the action and evaluation stages yielded the impact of the PDP. Figure 4 shows the triangulation at the diagnostic stage. The outer hexagon shows the participants while the inner one presents the six instruments and their findings. The commonalities are included in the circle.

Teachers’ Main Quality Features

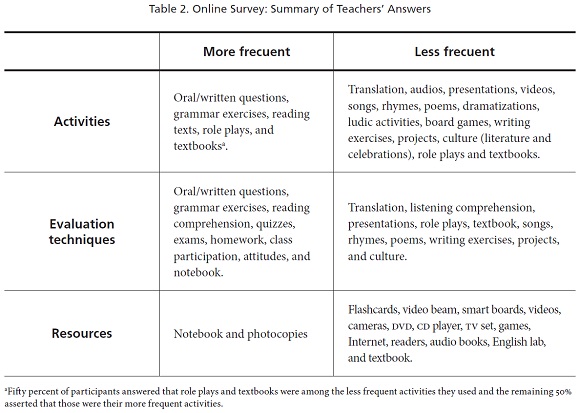

A data base, paper and online surveys, a focus group, and documentary analysis yielded the information. Most English teachers in the public schools in Cali are a mature population with long experience teaching English in high school; they abide by traditional approaches; research is either absent or is not central in their curriculum; they are not fully acquainted with the use of information and communication technologies (ICT), and they resort to traditional resources. Table 2 shows features regarding teachers’ methodology, evaluation, and resources.

A lack of graduate studies in the city related to English teaching has made teachers resort to PDPs, methodology, and language courses. On the other hand, the predominant teachers’ language level according to their answers, B1 (Council of Europe, 2001), was confirmed with the results of the language tests administered by the Ministry of Education. This fact reflects the teachers’ awareness about their level. This level corresponds to the reality of a monolingual Spanish speaking society. Another interesting finding was related to the teachers’ vocation; they permanently pursue the improvement of their students.

Teachers’ Professional Needs

This second category was divided into five elements: knowledge, practice, image, awareness, and situational constraints.

- Knowledge: Teachers needed to improve language proficiency, methodology (knowledge of modern approaches), and views of language and language learning.

- Practice: Teachers needed to strengthen lesson planning, students’ motivation, classroom management, use of resources, implementation of modern methods and approaches, and assessment.

- Image: Teachers needed to enhance their motivation, attitudes, values, and rapport with students, colleagues, parents, and school stakeholders. The teachers’ level of qualification, experience, language proficiency, and methodology also required improvement as perceived by themselves and by others.

- Awareness: Although the teachers were aware of their strengths and weaknesses, they lacked systematic reflection and research about their context, which is necessary to introduce changes in their settings.

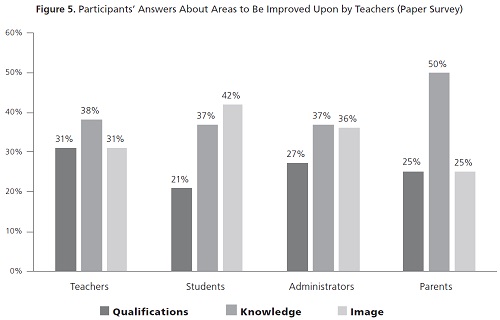

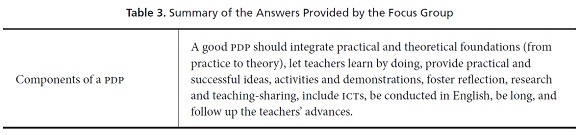

- Situational constraints: lack of resources, insufficient time on task, large class size, students’ demotivation, lack of parents’, principals’, co- ordinators’, and stakeholders’ support, few PDPs that address their professional needs, and scarce time availability. All these constraints impede undertaking research, reading and writing on professional experience, and undermine both the teachers’ internal and external image. The paper and online surveys were the instruments that yielded more information about the areas that the teachers needed to improve upon (see Figure 5 and Table 3).

PDP Components

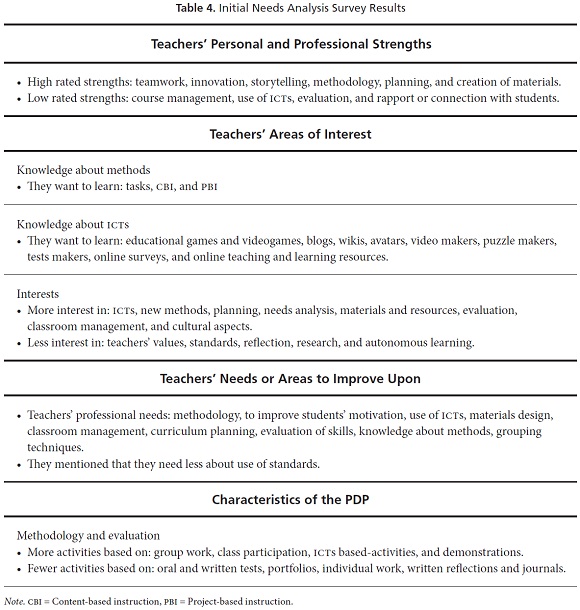

The components emerged from the surveys, focus group (see Table 3), and needs analysis survey (see Table 4). They included current methods, ICTs, and rapport with students. It was surprising to learn about the teachers’ low curiosity on classroom research and standards. Nevertheless, classroom research, in the form of reflection and needs analysis, was incorporated as a cross component of the PDP, while standards were integrated in lesson planning and evaluation.

The PDP contents and objectives were negotiated with the teachers; the eclectic approach followed a practice-reflection-theory cycle that allowed the teachers to learn, apply, and reflect on the contents and the theory. The materials and resources were up-to-date, affordable, available, and handy; finally, the instructors and teachers’ attitudes contributed to a good learning environment. The PDP design responded to the teachers’ needs and interests opposing the common parameters of previous PDPs taken by the teachers, not separating theory from practice and proceeding in a non-linear sequence.

Based on the data gathered, we can now briefly summarize the components of the designed PDP:

- Knowledge regarding methodology and language proficiency: current methodologies (Content and Language Integrated Learning [CLIL] and Task Based Learning [TBL]) and motivation strategies (rhymes, games, tongue twisters). The program was conducted in English to increase the teachers’ language level.

- Practice involving planning, evaluation, use of resources, classroom management: needs analysis, use of standards, planning, use and creation of resources (board games and electronic materials), use of ICTs, and evaluation strategies.

- Awareness: reflection and classroom research.

- Image: rapport, values, and professional attitudes.

Impact of PDP on Teachers’ Practices

This section includes the fourth category subdivided into knowledge, practice, image, and awareness.

- Knowledge of current methods (TBL and CLIL) was evident in the teachers’ class performance, lesson plans and class recordings.

- Language level progress was noticed as teachers started using more English and incorporating terminology related to tasks and CLIL; their accuracy in pronunciation and vocabulary increased.

- Practice of new methods and strategies and use of new materials and resources were also observed through the documents teachers provided and through the design of new digital materials, such as PowerPoint games, the use of ICTs, and the introduction of warm-up activities in their lessons.

- Rapport with students and self-image as persons and professionals were noticed in teachers’ higher motivation, autonomous learning, commitment, eagerness to implement and report the new strategies they applied, and in the acquisition of new resources for the English class like video beams, TV set, and a classroom for this subject. The motivation arose from the teachers’ fulfillment of their expectations and the development of their abilities.

- Awareness to evaluate their practices and their effectiveness on students’ learning by implementing needs and interests analysis with their students. The teachers highlighted the importance of collecting data with this tool, which allowed them to evaluate their students’ and their own needs, interests, and performance.

The action and evaluation stages also let us identify the successful features and dif-ficulties of the PDP piloting. Its most fruitful components were the needs analysis, contents, objectives, methodology, materials, evaluation, the instructors, and the participants’ attitudes. These findings were drawn from the work-shops evaluation formats, focus group, and documentary analysis.

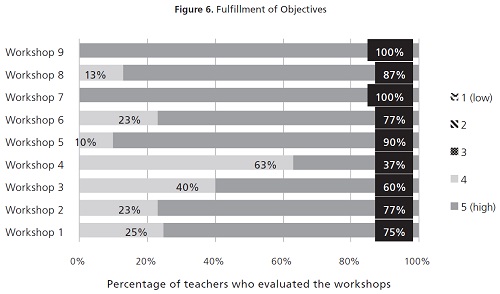

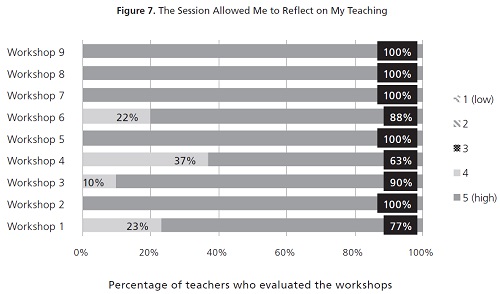

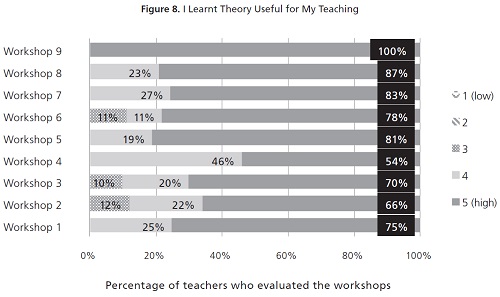

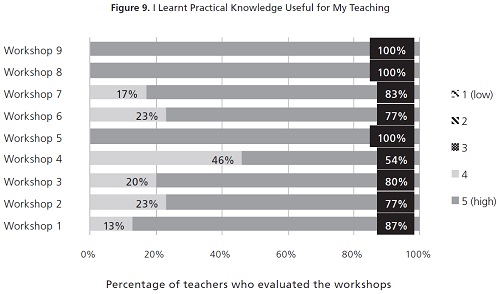

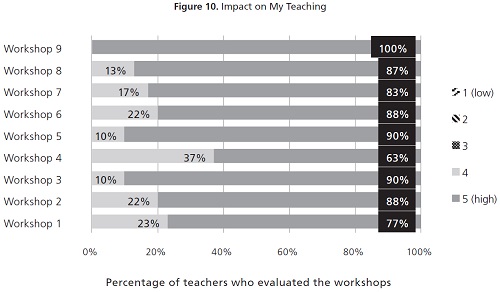

Evaluation Formats’ Results

The format consisted of two sections. Section 1 evaluated five aspects of the PDP with a 1 (low) to 5 (high) scale: fulfillment of objectives, teaching awareness, theoretical bases, practical knowledge, and impact of the workshops on the teachers’ practices. In Section 2, open indirect questions detected the particular views of teachers regarding their learning, the positive aspects, and the aspects to improve upon in the program. A section of comments let them express other opinions. Figures 6 to 10 show the percentages of the teachers’ answers to each of the five aspects evaluated in Section 1.

The fact that most teachers gave a score of 5 and 4 showed that the PDP braced the teachers’ needs and expectations. The teachers reported in Section 2 what they learned:

- About ICTs: creation of blogs, Voki avatars, the use of computer and programs in general.

- Teaching strategies: design and use of resources, be creative, apply games, needs analysis survey design, rhymes, tell stories, explore a commercial program, and rubrics design.

- Theoretical and practical background on methods: theory on methods, tasks, CLIL, TBL, lesson plans, how to integrate CLIL, TBL and ICTs.

- Teachers’ awareness, motivation and learning: The workshops let the teachers reflect on and share their teaching practices and learning strategies, learn from their mistakes, enjoy the classes, motivate the students, think of the necessity of being a creative teacher, integrate topics to teach, learn, and improve their lessons, plan better lessons, and have a different view of language as a communication tool.

- Features of the course and instructors: The course was dynamic and creative; the instructors were patient and clear.

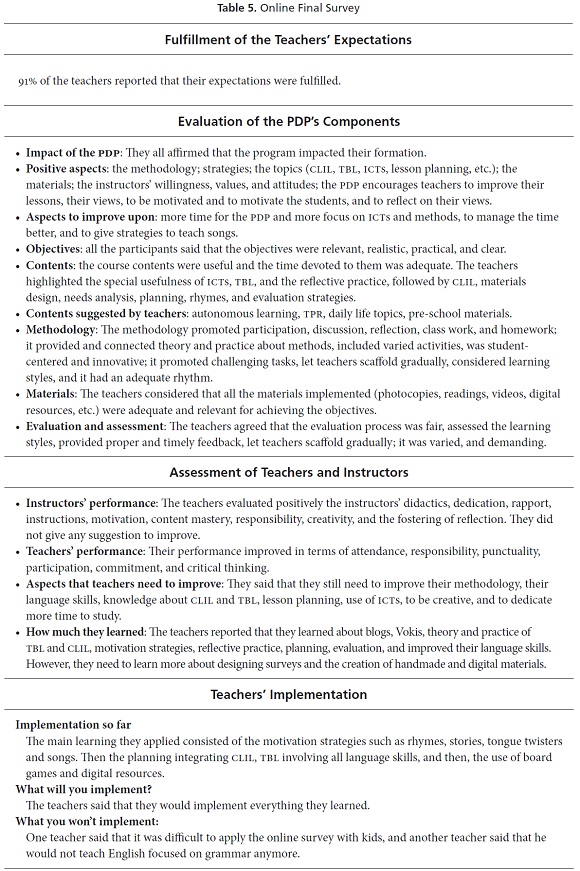

The final survey (Table 5) also evaluated the impact of the PDP.

Results of the Focus Group

The teachers’ answers were paraphrased.

- Why did you decide to come and stay in this program? They came because:

- They were interested in learning.

- They wanted to improve their teaching practices and language skills.

- They had good recommendations about the instructors.

- The group had a good atmosphere and created good relationships.

- They enjoyed and learned throughout the course.

- They achieved their expectations.

- The program offered practical ideas, strategies, and real life situations to implement in the classroom.

- They were getting more practice.

- They wanted to improve for the students.

- They were open-minded to new changes.

- Could you tell us what you have implemented so far and the results?

- What did you improve in this program? They said that they improved their English level and the way of teaching in a communicative way; they also improved their methodology and lesson planning.

They stayed because:

Teacher 1: She has used more English in her classroom; she has changed her views about grammar; she has noticed the effects of tongue twisters on students’ motivation, and she showed her blog to her students.

Teacher 2: He has implemented the tongue twisters; he bought his own video beam; he asked for and got a room for the English class; he has changed his mind, he said: “The teacher who talks the more in class, is a bad teacher.”

Teacher 3: She has implemented the needs analysis survey; she shared her new knowledge with other colleagues.

Teacher 4: She has implemented TBL; she has involved more communication in her classes.

Teacher 5: She has implemented warm up activities; she has changed her attitudes; she has implemented games, and she was teaching content.

Teacher 6: She has fostered new changes in the school; the teachers talked to the principal to a get a TV set, an English classroom, air conditioning, a sound system, and a PC.

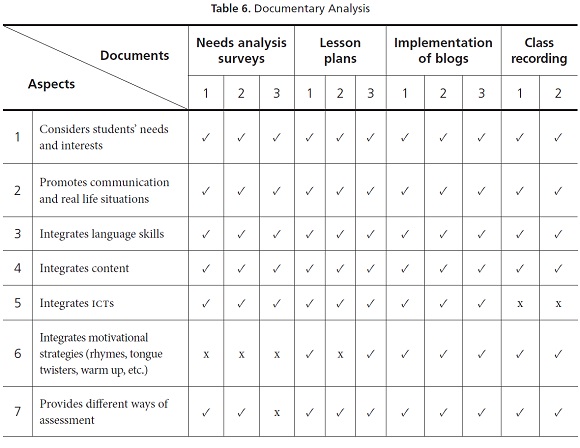

Documentary Analysis Results

Three random samples of each document, except for the class recordings, were taken to follow up on the teachers’ implementation of the new learning. Table 6 shows this implementation as seen in the documentary analysis.

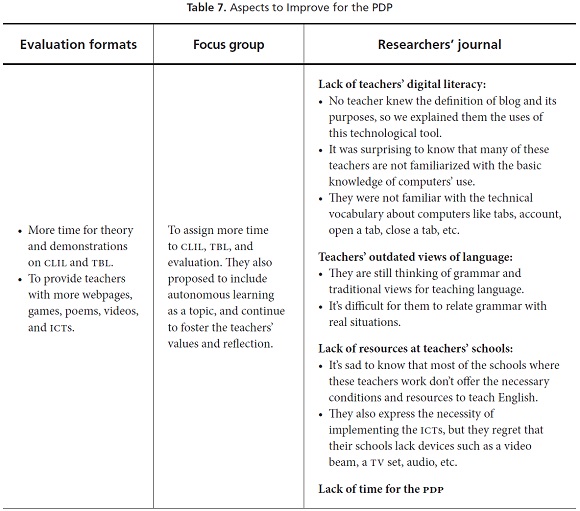

Table 7 presents the aspects to improve from the evaluation formats, focus group, and researchers’ journal.

Conclusions and Pedagogical Implications

This study allowed the researchers to understand that a PDP should impact the teachers’ teaching practices and views, raise their personal and professional awareness, increase their motivation and attitudes toward their own learning and teaching processes, and improve their language proficiency. To do so, the PDP should be constructed from the teachers’ needs, interests, learning styles, and learning pace combining the experts’ guidance, the sharing among participant teachers, and autonomous exploration. Conditions of time, group size and availability of resources are crucial for the effectiveness of PDPs.

A key result of this study is that practical and theoretical usefulness (applicability) is a powerful motivational source for teachers since their chief wish is to learn strategies and tools they can try in their classrooms. In-depth knowledge on current trends instead of historical overviews of methods is well received by the teachers. Rhymes, stories, games and tongue twisters result to be motivational and effective teaching strategies that represent a different view to teach vocabulary, structures, pronunciation, and fluency.

The integration of topics, resources, and methodology in every session is a good alternative to the linear sequence of separate courses for language, methodology, culture, and research that usual PDPs adopt. Furthermore, practical applicability is directly related to the impact of PDP. If theoretical or practical knowledge is considered useful by the teachers, it will probably be incorporated by them in their teaching.

The practice-reflection-theory cycle means an inductive approach to theory allowing teachers to infer the principles behind practice. Starting sessions with practical demonstrations followed by reflection and ending with theory prove to be effective in promoting teachers’ critical analysis and comprehension of their practices and in allowing them to connect them with underlying principles. This sequence is more coherent with the TBL communicative approach adopted.

Modern PDPs should aim at catering the 21st century challenges for teachers. Blending CLIL, TBL, and ICTs represents an effective way to help teachers improve their students’ motivation and learning of English. ICTs, being both content and tools, are necessary for conducting a PDP. Moreover, the teachers’ digital literacy should be tested first since most of them are challenged by the advanced technology changes. Then, an introductory basic workshop on computer management is required.

Additionally, a PDP requires enough time to let instructors and teachers fulfill their expectations and let both participants work on a number of practical demonstrations and microteachings. Furthermore, the key to success of a PDP lies not only in its contents and methodology, but also in the participants’ attitudes and factors such as motivation, commitment, punctuality, attendance, willingness to change, and open-mindedness to try new things. In a nutshell, the effectiveness and impact of a PDP should be reflected on, first, the instructors’ and teachers’ achievement of goals; second, the impact of this new learning on students’ performance, and third, the support by parents and school administrators.

All in all, the close connections between teacher quality and professional development programs were proved and it was established that they are complex and depend on internal and external factors. More research on these topics is needed in Colombia; it is necessary to open the discussion not only about the significance and development of TQ, PD, PDP, but also about teacher hiring in the public sector for establishing a coherent PD policy for language teachers and finding the best teachers based on their merits. Also, the Colombian bilingualism policies require adequate theoretical support about TQ and PD and proper conditions for securing the quality of teachers.

It should be noted, however, that the findings, implications, and recommendations in this research refer to a particular setting, that of a small group of teachers who were especially motivated towards their professional growth. Further studies about PDP in other settings like bigger groups of teachers, or teachers in only the public or only the private sector, or teachers with a different proficiency level, or with a different level of literacy might reach different outcomes. Likewise, longer PDPs, or ones with less resources, or taught by a single instructor or by teams of instructors can obtain other results. Generalizations are hardly to be extracted from these findings, although some of them are of great value like the eclectic and inductive theoretical and methodological approach to PDP. Instructors’ direct observations are also required to follow the teachers’ implementation in order to support them.

References

Bastidas, J. A., & Muñoz Ibarra, G. (2011). A diagnosis of English language teaching in public elementary schools in Pasto, Colombia. HOW, 18(1), 95-111.

Cadavid Múnera, I. C., McNulty, M., & Quinchía Ortiz, D. I. (2004). Elementary English language instruction: Colombian teachers’ classroom practices. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 5(1), 37-55.

Cárdenas Beltrán, M. L., & Nieto Cruz, M. C. (2010). El trabajo en red de docentes de inglés [Teachers of English and their network]. Bogotá, CO: Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Carr, W., & Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming critical: Education, knowledge and action research. London, UK: Deakin University Press.

Cely, R. M. (2009, September). Perfil del docente de inglés [The profile of a teacher of English]. Lecture given at the First National Congress on Bilingualism, Armenia, Colombia.

Clotfelter, C. T., Ladd, H. F., & Vigdor, J. L. (2006). Teacher-student matching and the assessment of teacher effectiveness. The Journal of Human Resources, 41(4), 778-820.

Cochran-Smith, M., Feiman-Nemser, S., McIntyre, J., & Demers, K. (Eds.). (2008). Handbook of research on teacher education: Enduring questions in changing contexts. (3rd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Taylor and Francis.

Coggshall, J. G. (2007). Communication framework for measuring teacher quality and effectiveness: Bringing coherence to the conversation. Washington, DC: National Comprehensive Center for Teacher Quality.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2007). Research methods in education. (6th ed.). London, UK: Routledge Falmer.

Council of Europe. (2001). Common European Framework for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2007). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Darling-Hammond, L. (1998). Teachers and teaching: Testing policy hypotheses from a national commission report. Educational Researcher, 27(1), 5-15. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X027001005.

Darling-Hammond, L. (1999). Teacher quality and student achievement: A review of State policy evidence. Washington, DC: University of Washington, Center for the Study of Teaching and Policy.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2006). Powerful teacher education: Lessons from exemplary programs. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Darling-Hammond, L., & Bradsford, J. (Eds.), (2005). Preparing teachers for a changing world: Report of the committee on teacher education of the national academy of education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Hanushek, E. A., & Rivkin, S. G. (2007). Pay, working conditions, and teacher quality. Future Child, 17(1), 69-86. https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.2007.0002.

Harris, J., & Ó Duibhir, P. (2011). Effective language teaching: A synthesis of research. Dublin, IE: National Council for Curriculum and Assessment, NCCA.

Johnson, S. M. (2006). The workplace matters: Teacher quality, retention, and effectiveness. Washington, DC: National Education Association, NEA.

Kane, T. J., Taylor, E. S., Tyler, J. H., & Wooten, A. L. (2011). Evaluating teacher effectiveness. Education Next, 11(3), 55-60.

Kennedy, M. (2008). Sorting out teacher quality. Phi Delta Kappan, 90(1), 59-63. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172170809000115.

Kostina, I., & Hernández, F. (2007). Competencia profesional del docente de lenguas extranjeras [Professional competence of the foreign languages teacher]. In A. Aragón, I. Kostina, M. Pérez, G. Rincón, (Eds.) Perspectivas sobre la enseñanza de la lengua materna, las lenguas y la literatura (pp. 81-99). Cali, CO: Facultad de Educación de la Pontificia Universidad Javeriana.

Kunter, M., Klusman, U., Baumert, J., Richter, D., Voss, T., & Hachfeld, A. (2013). Professional competence of teachers: Effects on instructional quality and student development. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(3), 805-820. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032583.

McNulty, M., & Quinchía Ortiz, D. I. (2007). Designing a holistic professional development program for elementary school English teachers in Colombia. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 8(1), 131-143.

National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE). (2004). Teacher quality. Retrieved from http://www.ncte.org/governance/teacherQuality.

Paone, J., Whitcomb, J., Rose, T., & Reichardt, R. (2008). Shining the light II: State of teacher quality, attrition and diversity in Colorado 2008. Colorado, US: The Alliance for Quality Teaching.

Richards, J. C., & Farrell, T. S. C. (2005). Professional development for language teachers: Strategies for teacher learning. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667237.

Rivkin, S. G., Hanushek, E. A., & Kain, J. F. (2005). Teachers, schools, and academic achievement. Econometrica, 73(2), 417-458. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0262.2005.00584.x.

Sánchez Jabba, A. (2013). Bilingüísmo en Colombia [Bilingualism in Colombia]. Cartagena, CO: Centro de Estudios Económicos Regionales del Banco de la República.

Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner. San Franciso, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Valentine, J. C., Rakes, C. R., & Canada, D. (2010). Predicting student outcomes from information knowable at the time of hire: A systematic review. Louisville, KY: University of Louisville.

Villegas-Reimers, E. (2003). Teacher professional development: An international review of the literature. Paris, FR: UNESCO, International Institute for Educational Planning.

Wallace, M. J. (1991). Training foreign language teachers: A reflective approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Whitcomb, J., & Rose, T. (2008). Teacher quality: What does the research tell us? In J. Paone (Ed.), Shining the light II: Illuminating teacher quality, diversity, and attrition in Colorado (pp. 5-35). Denver, CO: Alliance for Teacher Quality.

Wright, A. C. (2012). A literature review on the determinants of teacher performance. Santa Barbara, CA: University of California.

Zumwalt, K., & Craig, E. (2005). Teachers’ characteristics: Research on the indicators of quality. In M. Cochran-Smith & K. M. Zeichner (Eds.), Studying teacher education: The report of the AERA panel on research and teacher education (pp. 157-260). Mahwah, NJ: Laurence Erlbaum Associates.

About the Authors

Orlando Chaves holds a BA in Philology and Languages (Universidad Nacional de Colombia), an MA in Spanish and Linguistics (Universidad del Valle, Colombia) and an MA in English Teaching (Universidad de Caldas, Colombia). His professional interests are applied linguistics, EFL Didactics and TD. He is a member of EILA research group and ASOCOPI.

Maria Eugenia Guapacha holds a BA in Foreign Languages (Universidad del Valle, Colombia) and an MA in English Teaching (Universidad de Caldas, Colombia). Her professional interests are applied linguistics, ESP, EFL didactics, pedagogy; ICTs and TD. She has taught at all educational levels in both the private and public sectors.

Appendix: Sample of a PDP Workshop

Workshop 5

Two New Best Friends in my Lessons: CLIL and TBL

Time: 5 Hours

Topics: CLIL and TBL

Objectives:

- To provide teachers with clear illustrations and concepts on the way CLIL and TBL work in class.

- To have teachers contrast traditional and current methodologies.

- To encourage teachers to incorporate CLIL and TBL in their teaching.

- To improve the teachers’ teaching and learning of the four skills.

Activities:

Activity 1: Warm up

Reviewing theory about CLIL and TBL

The session will start with review questions about CLIL and TBL

- What do CLIL and TBL stand for?

- What are the principles of CLIL?

- What is a Task?

- What is the structure of a Task?

Activity 2: Going deeper into tasks concept

The teachers will watch a video about TBL to complement the theory about this method. They will receive a handout following a pre-, while- and post- sequence to support their comprehension (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d-YEwo8FTqk). At the end of the video, the teachers will share their answers.

Instructions: Follow a pre-, while- and post- sequence to support the teachers’ comprehension of the video. Pause appropriately to let the teachers complete the handout.

Activity 3: Going deeper into the concept of CLIL

The teachers will watch two more videos about CLIL to complement the theory about this method. They will answer these questions:

Video 1: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uIRZWn7-x2Y

- When implementing CLIL, what is more important: language or content? Or, do they both have the same status?

- Which authors support CLIL?

- What is the difference between CLIL and immersion?

- Mention the key concepts of CLIL

Video 2: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xiQRbB9_1zs

Say true or false:

- CLIL involves experiential learning

- Students learn more than language

Explain the example given in the video about the carrot diagram.

Activity 4: Illustrating the use of tasks and CLIL

First, the instructors will illustrate how to integrate tasks, language, and content through an example:

Topic: the circulatory system

Content: function of the circulatory system and illnesses

Language: vocabulary related to the topic such as veins, blood, system, arteries, etc. Expressions like it is composed of, verbs like run, circulate, etc.

Tasks: doing diagrams, posters, presentations on other body systems.

Then, the instructors will provide a list of topics for teachers to form groups of three and design a poster following the pattern given (topic, content, language, task).

- Group 1: Creating shopping lists for (a) a birthday party, (b) breakfast, and (c) lunch

- Group 2: Healthy food

- Group 3: Creating a mini-brochure about Cali: where to go for cultural activities, where to go for fun, where to practice sports, where to eat typical food, etc.

- Group 4: Presenting animal species in danger of extinction

After having designed the lessons, the group of teachers will present the poster to the whole class. They will receive feedback from the instructors and classmates as well.

Activity 5: Closing, reflection and evaluation: CLIL and tasks in our EFL teaching

In pairs (Teachers A and B) will talk about the advantages and disadvantages of both CLIL and TBL, as well as their application in our schools. Teacher A will report advantages and Teacher B disadvantages. The instructors will wrap up the teachers’ comments, and will conclude by (a) remarking on the need of changing current predominant emphasis on grammar-centered views, and (b) on the possibility of integrating tasks and CLIL.

Instructions: Mention that TBL requires careful planning of the tasks; the final product of each task must be clear for the students. Note the usefulness of teamwork required by tasks for large classes. Regarding CLIL, highlight the option of working collaboratively with teachers from other subject areas or of taking topics from those areas to “recycle” them in English, profiting from the fact that the topic is already known to the students. Refer the teachers to read the following authors: Jane Willis, David Nunan, and Jack Richards to complement their background on their own.

Resources: A computer room, video beam or TV set, copies (evaluation formats) and handouts, board, markers, and online videos.

Evaluation: Teachers’ participation will be used to assess their general comprehension of the concepts of tasks and CLIL. The handout will be checked in class.

The instructors will evaluate the teacher’s knowledge and comprehension on CLIL and TBL principles and procedures when planning tasks and CLIL in groups.

As usual, the teachers will also self-evaluate their progress and achievements through their reflections in the workshop evaluation format.

Homework: The teachers will bring a lesson plan and syllabi for Session 7. They will work in groups integrating tasks and CLIL in those lessons and syllabi after having a practical demonstration.

Reminder: Explore the digital games for Workshop 6 and develop the blog for Session 8.

Finally, the teachers will evaluate Workshop 5.

References

Bastidas, J. A., & Muñoz Ibarra, G. (2011). A diagnosis of English language teaching in public elementary schools in Pasto, Colombia. HOW, 18(1), 95-111.

Cadavid Múnera, I. C., McNulty, M., & Quinchía Ortiz, D. I. (2004). Elementary English language instruction: Colombian teachers’ classroom practices. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 5(1), 37-55.

Cárdenas Beltrán, M. L., & Nieto Cruz, M. C. (2010). El trabajo en red de docentes de inglés [Teachers of English and their network]. Bogotá, CO: Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Carr, W., & Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming critical: Education, knowledge and action research. London, UK: Deakin University Press.

Cely, R. M. (2009, September). Perfil del docente de inglés [The profile of a teacher of English]. Lecture given at the First National Congress on Bilingualism, Armenia, Colombia.

Clotfelter, C. T., Ladd, H. F., & Vigdor, J. L. (2006). Teacher-student matching and the assessment of teacher effectiveness. The Journal of Human Resources, 41(4), 778-820.

Cochran-Smith, M., Feiman-Nemser, S., McIntyre, J., & Demers, K. (Eds.). (2008). Handbook of research on teacher education: Enduring questions in changing contexts. (3rd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Taylor and Francis.

Coggshall, J. G. (2007). Communication framework for measuring teacher quality and effectiveness: Bringing coherence to the conversation. Washington, DC: National Comprehensive Center for Teacher Quality.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2007). Research methods in education. (6th ed.). London, UK: Routledge Falmer.

Council of Europe. (2001). Common European Framework for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2007). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Darling-Hammond, L. (1998). Teachers and teaching: Testing policy hypotheses from a national commission report. Educational Researcher, 27(1), 5-15. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0013189X027001005.

Darling-Hammond, L. (1999). Teacher quality and student achievement: A review of State policy evidence. Washington, DC: University of Washington, Center for the Study of Teaching and Policy.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2006). Powerful teacher education: Lessons from exemplary programs. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Darling-Hammond, L., & Bradsford, J. (Eds.), (2005). Preparing teachers for a changing world: Report of the committee on teacher education of the national academy of education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Hanushek, E. A., & Rivkin, S. G. (2007). Pay, working conditions, and teacher quality. Future Child, 17(1), 69-86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/foc.2007.0002.

Harris, J., & Ó Duibhir, P. (2011). Effective language teaching: A synthesis of research. Dublin, IE: National Council for Curriculum and Assessment, NCCA.

Johnson, S. M. (2006). The workplace matters: Teacher quality, retention, and effectiveness. Washington, DC: National Education Association, NEA.

Kane, T. J., Taylor, E. S., Tyler, J. H., & Wooten, A. L. (2011). Evaluating teacher effectiveness. Education Next, 11(3), 55-60.

Kennedy, M. (2008). Sorting out teacher quality. Phi Delta Kappan, 90(1), 59-63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/003172170809000115.

Kostina, I., & Hernández, F. (2007). Competencia profesional del docente de lenguas extranjeras [Professional competence of the foreign languages teacher]. In A. Aragón, I. Kostina, M. Pérez, G. Rincón, (Eds.) Perspectivas sobre la enseñanza de la lengua materna, las lenguas y la literatura (pp. 81-99). Cali, CO: Facultad de Educación de la Pontificia Universidad Javeriana.

Kunter, M., Klusman, U., Baumert, J., Richter, D., Voss, T., & Hachfeld, A. (2013). Professional competence of teachers: Effects on instructional quality and student development. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(3), 805-820. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0032583.

McNulty, M., & Quinchía Ortiz, D. I. (2007). Designing a holistic professional development program for elementary school English teachers in Colombia. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 8(1), 131-143.

National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE). (2004). Teacher quality. Retrieved from http://www.ncte.org/governance/teacherQuality.

Paone, J., Whitcomb, J., Rose, T., & Reichardt, R. (2008). Shining the light II: State of teacher quality, attrition and diversity in Colorado 2008. Colorado, US: The Alliance for Quality Teaching.

Richards, J. C., & Farrell, T. S. C. (2005). Professional development for language teachers: Strategies for teacher learning. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667237.

Rivkin, S. G., Hanushek, E. A., & Kain, J. F. (2005). Teachers, schools, and academic achievement. Econometrica, 73(2), 417-458. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0262.2005.00584.x.

Sánchez Jabba, A. (2013). Bilingüísmo en Colombia [Bilingualism in Colombia]. Cartagena, CO: Centro de Estudios Económicos Regionales del Banco de la República.

Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner. San Franciso, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Valentine, J. C., Rakes, C. R., & Canada, D. (2010). Predicting student outcomes from information knowable at the time of hire: A systematic review. Louisville, KY: University of Louisville.

Villegas-Reimers, E. (2003). Teacher professional development: An international review of the literature. Paris, FR: UNESCO, International Institute for Educational Planning.

Wallace, M. J. (1991). Training foreign language teachers: A reflective approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Whitcomb, J., & Rose, T. (2008). Teacher quality: What does the research tell us? In J. Paone (Ed.), Shining the light II: Illuminating teacher quality, diversity, and attrition in Colorado (pp. 5-35). Denver, CO: Alliance for Teacher Quality.

Wright, A. C. (2012). A literature review on the determinants of teacher performance. Santa Barbara, CA: University of California.

Zumwalt, K., & Craig, E. (2005). Teachers’ characteristics: Research on the indicators of quality. In M. Cochran-Smith & K. M. Zeichner (Eds.), Studying teacher education: The report of the AERA panel on research and teacher education (pp. 157-260). Mahwah, NJ: Laurence Erlbaum Associates.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Adriana González-Moncada. (2021). On the Professional Development of English Teachers in Colombia and the Historical Interplay with Language Education Policies. HOW, 28(3), p.134. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.28.3.679.

2. Brian P. Zoellner, Richard H. Chant, Kosze Lee. (2017). Do We Do Dewey? Using a Dispositional Framework to Examine Reflection Within Internship Professional Development Plans. The Teacher Educator, 52(3), p.203. https://doi.org/10.1080/08878730.2017.1316623.

3. Diego Fernando Macías, Wilson Hernández-Varona. (2022). An Overview of Dominant Approaches for Teacher Learning in Second Language Teaching. HOW, 29(1), p.212. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.29.1.631.

4. Ufuk ULUÇINAR. (2022). Teori Tabanlı Değerlendirmeye Dayalı Eklektik Bir Program Geliştirme Modeli. Ahi Evran Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, 8(1), p.132. https://doi.org/10.31592/aeusbed.1030701.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.