Published

Argumentation Skills: A Peer Assessment Approach to Discussions in the EFL Classroom

Habilidades de argumentación: un enfoque de evaluación por pares a los debates en el aula de inglés como lengua extranjera

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n2.53314Keywords:

Argumentation skills, experience, peer assessment (en)evaluación por pares, experiencia, habilidades de argumentación (es)

This paper presents an exploratory action research study carried out by two English as a foreign language teachers in a private, non-profit institution in Bogota, Colombia, with a group of 12 learners in a B1 English course. These students faced difficulties elaborating on their ideas when discussing issues in class. The study placed emphasis on the use of argumentation outlines and peer assessment to boost learners’ argumentative abilities. Audio-taped conversations and open-ended interviews were used to understand the impact on the pedagogical intervention. Findings revealed that argumentation outlines and peer assessment can promote learners’ awareness and ability to engage in argumentation processes. Moreover, peer assessment appears to be an essential tool for enhancing personal and collaborative learning, as well as for promoting learner reflection and agency.

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n2.53314

Argumentation Skills: A Peer Assessment Approach to Discussions in the EFL Classroom

Habilidades de argumentación: un enfoque de evaluación por pares a los debates en el aula de inglés como lengua extranjera

Diego Fernando Ubaque Casallas*

Freddy Samir Pinilla Castellanos**

Centro Cultural Colombo Americano, Bogotá, Colombia

*dubaque@javeriana.edu.co

**fpinilla@colombobogota.edu.co

This article was received on October 1, 2015, and accepted on March 28, 2016.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Ubaque Casallas, D. F., & Pinilla Castellanos, F. S. (2016). Argumentation skills: A peer assessment

approach to discussions in the EFL classroom. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 18(2), 111-123. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n2.53314.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This paper presents an exploratory action research study carried out by two English as a foreign language teachers in a private, non-profit institution in Bogota, Colombia, with a group of 12 learners in a B1 English course. These students faced difficulties elaborating on their ideas when discussing issues in class. The study placed emphasis on the use of argumentation outlines and peer assessment to boost learners’ argumentative abilities. Audio-taped conversations and open-ended interviews were used to understand the impact on the pedagogical intervention. Findings revealed that argumentation outlines and peer assessment can promote learners’ awareness and ability to engage in argumentation processes. Moreover, peer assessment appears to be an essential tool for enhancing personal and collaborative learning, as well as for promoting learner reflection and agency.

Key words: Argumentation skills, experience, peer assessment.

Este artículo presenta un estudio de investigación acción exploratoria llevado a cabo en una institución privada en Bogotá, Colombia, con un grupo de 12 estudiantes en un curso de inglés B1. Estos estudiantes enfrentaron dificultades al elaborar sus ideas al discutir temas de clase. El estudio usó esquemas de argumentación y una evaluación por pares para impulsar las habilidades argumentativas de los alumnos. Se analizaron conversaciones audio grabadas y entrevistas abiertas donde se reveló que los esquemas de argumentación y la evaluación por pares promueven el conocimiento y la capacidad de participar en los procesos de argumentación. La evaluación por pares resultó ser una herramienta fundamental para mejorar el aprendizaje personal y colaborativo, al igual que para promover la reflexión y actuación del alumno.

Palabras clave: evaluación por pares, experiencia, habilidades de argumentación.

Introduction

Language learning research in the English as a foreign language (EFL) field has often focused on the exploration and study of assessment practices as a way to improve learning (J. D. Brown, 1998). Importantly, the notable shift from structural teaching approaches to communicative, humanistic, and learner-centered approaches (Shaaban, 2005) has opened up space for teachers to see students as active constructors of knowledge (O’Malley & Valdez Pierce, 1996).

For H. D. Brown (2004), practices such as self and peer assessment involve students in their own destiny, encourage autonomy, and increase motivation. Peer assessment has then been considered uniquely valuable because it motivates students to be more careful in their work and amplifies their voice in the learning process (Black, Harrison, Lee, Marshall, & Wiliam, 2003). Nevertheless, not much has been documented in terms of assessment as a collaborative endeavor carried out by learners to claim ownership of their own learning processes.

For Cheng and Warren (2005), peer assessment has been more commonly incorporated into English language writing instruction where peers respond to and edit each other’s written work with the aim of helping with revision. Although psychological studies have shown that argumentation skills are associated with high-order cognitive skills, such as conceptual change (Nussbaum & Sinatra, 2003) and nonverbal reasoning (Mercer & Littleton, 2007), as well as with learning outcomes (P. Bell & Linn, 2000), little has been done in the EFL field to explore and document how learners can improve argumentation skills through oral tasks and the implementation of peer assessment practices.

Therefore, there is still a fertile ground for new research that has the potential to impact language learning from the learners’ perspective. The present paper presents a classroom research study where peer assessment was used to improve learners’ oral argumentative skills. The study is based on the assumption that peer assessment is relevant for developing students’ critical thinking, communication, lifelong learning, and collaborative skills (Nilson, 2003), and for helping students to become realistic judges of their own performance, enabling them to monitor their own learning experience, rather than relying solely on their teachers for feedback (Crisp, 2007).

Theoretical Background

The Notion of Experience: The Value of Experience in Language Learning

This study takes on Kolb’s (1984) notion of experience. Kolb contends that experience is an essential element that cannot be left aside from the classroom as it is a crucial part of the learners’ learning process. According to Kolb in any learning activity, learning processes need to be seen as top priority since “each act of understanding is the result of a process of continuous construction and invention through the interaction processes of assimilation and accommodation” (p. 26). As for this, it is essential to see experience as the umbrella term to understand language learning processes. Kolb also argues that “experience provides conceptual bridges across life situations such as school and work, portraying learning as [a] continuous, lifelong process” (p. 33). Thus, learners’ experiences when starting to learn a new language can help account for linguistic as well as personal learning processes in the new language.

Learning through and from experience is a dimension that cannot be detached from the EFL classroom. For Dewey (1938),

if an experience arouses curiosity, strengthens initiative, and sets up desires and purposes that are sufficiently intense to carry a person over dead places in the future, continuity works in a very different way. Every experience is a moving force. Then, its value can be judged only on the ground of what it moves toward and into. (p. 14).

Hence, in order to make the learners’ experience of learning a language move away from instrumentalized views where only linguistic outcomes matter, one needs to acknowledge that learning through and from experience places learning in the context of our lived experience and participation in the world (Murrell, 2000).

Peer Assessment

Cohen (1994) contends that assessment plays an important role in processes of learning languages and should be included in the procedures of evaluating both the students’ language performance and the language learning process. In this respect, for assessment to be a meaningful component, it needs to involve learners actively (Keppell & Carless, 2006) so that the assessment process can be more transparent to them. As for this, J. D. Brown (1998) argues that assessment requires learners to judge both their own performance learning a language and that of their peers. Then, peer assessment practices will give not only teachers but also learners a clearer view of the actual learning processes.

Peer assessment is particularly congruent with active and self-regulated learning, emphasizing students’ involvement and the development of social, cognitive, and meta-cognitive skills, some of which are professionally relevant (van den Berg, Admiraal, & Pilot, 2006). Peer assessment is thus an interesting alternative to help learners regulate and monitor their own learning (Lew, Alwis, & Schmidt, 2010). Because peer assessment requires students to closely judge their peers’ work, it seems to promote critical and reflexive thinking (Taras, 2010). Hence, peer assessment is more than an instrumental tool to evaluate learners’ performance; it may be considered more as an approach for learners to ponder upon and enhance their own learning experience. Moreover, since peer assessment can be considered as a form of peer tutoring (Donaldson, Topping, & Aitchison, 1996), there can be advantages for both tutor and tutee (Hartley, 1998). Then, peer assessment may have a positive impact upon all students’ behavior and attitude toward their own learning (Freeman, 1995), which makes it a valuable resource for teachers and learners in the EFL classroom.

Argumentation Skills

The development of spoken language skills is well documented (Wells, 1987). However, little has been said in terms of how argumentative skills, understood in this study as one of the components of communicative competence (Widdowson, 1978), are being developed in the EFL classroom.

Argumentation skills integrate both the capacity to make use of a linguistic repertoire and the capacity to use language with a communicative purpose. Although a communicative purpose can be achieved without the use of augmentation skills, we hold the view that argumentation must be conceived as a dialogic process in which opposing or similar claims meet, as well as a discourse mechanism whereby the user of the language can demonstrate his/her ability to use knowledge acquired for effective communication (Widdowson, 1978).

People use arguments on a daily basis for different purposes, like persuasion, negotiation, debate, consultation, and resolving differences of opinion (van Eemeren, Grootendorst, & Henkemans, 1996); thus, “argumentation or the use of arguments plays a critical role in the development of critical thinking and in developing a deep understanding of complex issues and ideas” (Deane & Song, 2014, p. 100). Actually, argumentation is a fundamental cognitive skill required for the 21st century thinking citizen (Kuhn & Crowell, 2011).

The ability to generate and evaluate sound arguments has received increasing recognition as fundamental to good thinking (Mercier, 2011), since “argumentation is a dialogue in which participants may take many different positions and change their minds as it proceeds” (Deane & Song, 2014, p. 100). Therefore, argumentation skills are not detached from Hymes (1972) and Bachman’s (1990) notion of communicative competence that has to do with the functional use of language. Both authors emphasize interaction among learners and the use of meaningful and contextualized language.

Context of the Study

This study was carried out in an adult English program at a private, non-profit English institution in Bogota, Colombia. In order to promote the students’ language ability, the institution assists them in becoming autonomous learners by providing them with different learning strategies and tools they have to put into practice during the learning process. The institution’s learning and teaching philosophy builds on cooperative learning, defined as “group learning activity organized so that learning is dependent on the socially structured exchange of information between learners in groups and in which each learner is held accountable for his or her own learning and is motivated to increase the learning of others” (Olsen & Kagan, 1992, p. 8) to organize and orient pedagogical and learning practices.

The study involved the authors as teacher researchers and a class of 12 young-adult learners whose ages ranged from 20 to 36 years. The learners’ proficiency corresponds to level B1 as defined by the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR). They participated for a period of six months in a number of class activities and interviews conducted by the researchers. The purpose of the interviews was to provide an account of the learners’ language learning processes on the development of argumentation skills through a process of peer assessment, whereby learners could document and keep track of their own involvement in the learning process (Keppell & Carless, 2006).

Diagnosis

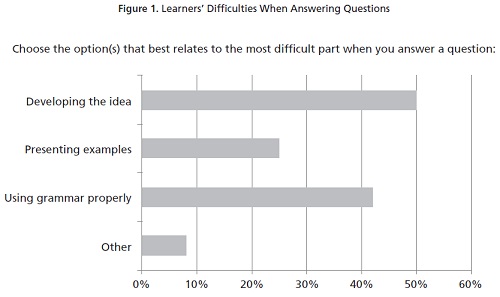

When exploring communicative activities in the classroom, informal assessment exercises made it evident that learners were feeling neither confident nor at ease with the oral skills they had to put into practice when discussing issues in class. In order to understand their perceptions, learners were invited to participate in an online survey that aimed at documenting how their language learning processes had been carried out regarding oral skills. In the first part of the survey, learners were asked to choose the area they had the most difficulty with when answering a question (see Figure 1).

Fifty percent of the participants seemed to be concerned with not having the ability to develop ideas as expected. Some of the comments they wrote for this question reinforce this perception:

Because there are some cases where I don’t have enough knowledge about the specific topic to argument the answer. (S1)1

Sometimes, I’m going around the bush. (S2)

I used to forget the structures when I speak. [sic] (S3)

Sometimes I feel afraid about my pronunciation and I have to make effort to express my ideas. [sic] (S4)

Because on moment I don’t remember the correct word. [sic] (S5)

I can’t find the words that I want to use for developing the ideas, I don’t know how begin to show all that I want to say. (S6)

(Survey, Question 1)

In the same survey, and in order to see whether learners’ performance was different when developing ideas in writing, they were asked to answer a question that had to do with poverty as a global issue: “What do you think about poverty as a global problem?” This short written exercise showed that most of the ideas presented in writing needed either more elaboration or were just too short. Some of the answers are presented below:

This is a mix of different causes: Discrimination and social inequality, wars also vulnerability to natural disasters. [sic] (S1)

In my opinion poverty is the general problem of the society, since around the world there are few people rich and they manage business, for example in Colombia the same families always govern. [sic] (S2)

As for my the poverty is an problem general for all person because when who in a society is poor, the other person even the rich people will be affect, only when the situation is regular for all people in the area, so all can be good and peace. [sic] (S3)

(Survey, Question 3)

Interestingly, when learners were asked what teachers had done in class to help them improve speaking skills, this is what they said:

Some of them said that in my experience as a language learner, teachers have done exercises about speaking in groups about different topics. [sic] (S4)

Well really many times, the teachers has showed how develop the argument but the students sometimes don’t get concept or don’t remember so when we need to use the method, it isn’t. [sic] (S2)

My teacher taught me words and expressions that I can say when I am speaking, and the teacher explained me the order that I can follow in order to improve argumentation skills. [sic] (S5)

(Survey, Question 4)

Although learners accounted for some learning experience, it had not been effective enough. According to their views, following the strategies presented by their teachers was not an easy task.

Method

This study took on methodological principles of action research. Action research was seen as a process in which planning, acting, observing, and reflecting (Newby, 2010) were pivotal to document and understand learners’ experiences on the pedagogical problem of this study. Nonetheless, and bearing in mind that as teachers we develop personal theories that are constructed in action and constituted reflexively in our everyday practice (Schön, 1983), action research was also selected because our aim as professionals was not only to improve learners’ abilities to elaborate on ideas but also to make sure that our pedagogical views were integrated in and reconstructed by developing the study.

Pedagogical Intervention

Newby’s (2010) conception of action research, planning, acting, observing, and reflecting were embraced as the guiding elements for the instructional component of the study; then, by acknowledging that our personal theories on this matter were relevant to constructing a more meaningful practice (Schön 1983), we began by putting together personal perspectives on the subject of argumentation. This collaborative endeavor came to its realization through lesson planning. Lesson planning was an essential element of the planning stage of the action research process through which we were able to map and envisage the acting processes.

Through lesson planning, assessment was addressed to be implemented and fostered from a collaborative peer-learning perspective. This collaborative view intended to empower learners to appraise the quality, value, and level of learning when they value their classmates’ interventions. This peer approach to assessment was further used to enhance learning and contribute to learning efficiency and quality (Al-Barakat & Al-Hassan, 2009).

The second stage of this intervention dealt with acting and observing. We implemented a previously configured set of activities that in essence was geared towards promoting oral argumentation skills and documenting how these skills might improve as a result of peer assessment practices in class discussions.

Data Collection and Findings

Data collected through audio recording of oral tasks and interviews were analyzed through content analysis procedures. This approach to scrutinize data is a general term for a number of different strategies used to analyze text (Powers & Knapp, 2006). Because content analysis is “a research method for the subjective interpretation of the content of text data through the systematic classification process of coding and identifying themes or patterns” (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005, p. 278), it was considered appropriate for determining and describing the characteristics of the oral data collected.

Learners’ Argumentation Skills in Oral Tasks

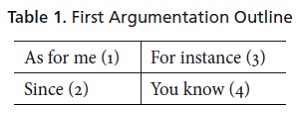

Oral tasks are best described here as communicative-oriented activities learners performed both during and at the end of a work unit. It was assumed that a task is an activity that places emphasis on meaning, involves communication and problem-solving, and relates to realworld situations (Skehan, 1998). Oral tasks were often supported by the use of reading material. Readings were used to provide learners with some information input and trigger further discussions. Reading is a situated activity in which the interaction of linguistic knowledge, background knowledge, and interpretative work are put together to make sense of the world that surrounds us (Baynham, 1995). Learners had the opportunity to read about topics they later had to talk about, and they were asked to follow a simple argumentation outline (see Table 1) to help them develop their ideas when speaking. They were expected to use the four expressions shown in Table 1.

The following transcriptions result from an oral task and illustrate the students’ use of argumentation skills following the outline shown in Table 1:

As for me the cultural has changed over time a lot since it was customary that the family was together the people was more formal than today, they people tend to be reserved for instance a lot person eat their food alone, in the same way before the people was more kind today dressed to very formal and they prefer to be reserved with the private life, you know your grandparents sure were formal with traditions customary. In a meeting had a formal etiquette and a good table manners whoever today we are more individual, a lot of times, the family aren’t together at the same time to eat we are informal you can see less ties on the street and the offices and the people likes to show their life through internet in addition our table manners are different since we are together to eat...aren’t we? [sic] (Oral task: How has culture changed over time? - John)

This oral task made it evident that John could follow the outline provided. However, when developing his idea a couple of problems emerged. Grammar seemed to be an area where little reflection or monitoring was made at the time of speaking. John was not aware of the mistakes made in this regard. Pronunciation was as well an area for improvement.

In the following examples, the outline was partially incorporated:

Yes, the culture has changed over time since I am not so older but I have seen some things that surprise me every day. I am going to tell you three examples to show you my opinion. So, first before the people were more respectful with other people, they always greeted someone when they go to someone’s house, but now teenagers do not greet anyone. Second, before there were a lot of taboos with some topics like parties, drugs, sex, boyfriend, but now or recently these topics are pretty normal and usual to talk these topics with anyone. Third, it is important to say that before when we wanted to visit someone you had to take to give something for instance some bread or maybe some fruit but as we can know now, nobody do that and it is so polite you know the time has changed and the culture too, it hasn’t? [sic] (Oral task: How has culture changed over time? - Carolina)

As for me, culture have been having a lot of changes through time, hasn’t it? Since the age when our grandparents were kids they were very innocent with topics that nowadays aren’t a taboo for children. For instance, they hadn’t yet now that the kids of the same age ask them knows but also the content of brands new clothes. [sic] (Oral task: How has culture changed over time? - David)

In all cases, the outline of argumentation provided forced the students indirectly to elaborate on their ideas. This linguistic feature placed emphasis on a deeper learning process. It had a bearing on how learners at the time of speaking modified and articulated new mental processes in order to adapt to the new communicative demands.

In each of the cases presented above, the outline was used differently. Arguably, the communicative intention of each learner as well as his/her vocabulary repertoire and grammatical competence modified the final outcome of the oral task. Of particular note here is that “speaking was more than making the right sounds, choosing the right words or getting the constructions grammatically correct” (Chastain, 1998, p. 330). Speaking or the ability of producing an accurate idea was contingent upon personal skills to incorporate the new outline of argumentation to make it work with previously learned schemas and the personal ability to modify existing information stored in memory.

After having found similar performances in other learners’ tasks, it was evident that just providing learners with an outline for argumentation was not enough. There was a need for a collaborative learning approach from which learners could benefit. Thence, oral tasks within the classroom incorporated an assessment follow-up process in which learners were expected to value their classmates’ efforts when participating in all discussions.

According to Davies (2006) peer assessment has been increasingly used as an alternative method of engaging students in the development of their own learning. As such, peer assessment could help students’ self-assessment by their judging the work of others and in turn gaining some insights regarding their own performances, since peer assessment is in essence a process in which students evaluate the performance or achievement of peers (Topping, Smith, Swanson, & Elliot, 2000). Thus, peer assessment was aimed at helping learners claim ownership of their own learning processes and classroom practices by having them make analytical judgments of oral tasks.

With respect to how peer assessment was approached by learners, the comment below illustrates the kind of oral interventions made in class during the follow-up process:

In my understanding, Carolina started her opinion with yes. She doesn’t use “as for me” to introduce her opinion. She explains her opinion with three arguments. In the first she tried to express that people were more respectful before but the first argument as for me it isn’t clear since I didn’t understand the verb that explain the action that people did before and teenagers don’t do in this moment. She describe with a great arguments the culture changes over time but she made a little mistakes in pronunciation for instance words like usual, talk, changed and use anybody instead of somebody. Finally, she made a grammar mistake in a final tag question: She said “the time has changed and the culture too, it hasn’t?” And the correct form is: the time has changed and the culture has changed too, haven’t they?” [sic] (Oral task: How has culture changed over time? Peer assessment comment, Leonardo)

In this assessment comment, a couple of ideas were brought forth. Firstly, there is a comment regarding how the argumentation outline provided was used by Carolina. Regarding this, it seems relevant to make use of the expression provided to state one’s opinion inasmuch as it can help ideas run smoothly. This expression is not just stating one’s opinion but also is making the transition for the following argument provided. Nevertheless, such assessment sheds light onto the personal yet linguistic schemas already put into practice. These schemas had to do with how learners as individuals expected others to make use of the argumentative outline when debating or discussing the given issues in class.

By valuing others’ interventions, peer assessment seemed to assist in the development of important argumentative skills, including reflection upon learners’ own argumentative skills (Mello, 1993), and the making of peer assessment an argumentative and metalinguistic/ communicative task. Secondly, another issue brought up had to do with the positive feedback provided. It was mentioned that “She describe with a great arguments the culture changes over time but she made a little mistakes in pronunciation for instance words like usual, talk, changed and use anybody instead of somebody” [sic]. Such appraisal worked to encourage the learner assessed to continue providing solid arguments when developing ideas.

Kolb’s (1984) notion of experience indicates that learners can become increasingly self-directed and responsible for their own learning. It can be argued that through the assessment of oral tasks learners created individual knowledge regarding their own argumentation skills and abilities to be used in connection with certain vocabulary. However, if knowledge is created through the transformation of experience as contended by Kolb, knowledge constructed by learners in this study was not only the result of the combination of grasping and transforming experience (Kolb, 1984), but also the result of a collaborative endeavor where peers co-constructed new learning schemas that helped modify the existing ones.

Learners’ Perceptions of Experience

Semi-structured interviews (J. Bell, 1999) were used to explore and document learners’ perceptions regarding the implementation of oral tasks and peer assessment. Learners participated in two individual interviews that took place at the end of a work unit. For Kvale and Brinkmann (2009), speaking of qualitative research, “interviews attempt to understand the world from the subjects’ points of view, to unfold the meaning of their experiences, to uncover their lived world prior to scientific explanation” (p. 1). Thus, interviewing was suitable for accessing personal perspectives on the experimented approach.

Data collected through interviews were analyzed to group learners’ perceptions. On this matter, learners made it evident that having used the outline of argumentations helped them perform more straightforward when discussing different topics. Of particular note is that most of the learners’ answers referred to peer assessment as a personal opportunity to contribute to others’ learning processes.

According to McDowell (1995) peer assessment is one form of innovation which aims to improve the quality of learning and empower students in contrast to more traditional methods, which can leave learners’ feeling disengaged from the overall assessment process. Then, peer assessment from the learners’ perspective was a means to an end. Through it, they performed not only as active participants of their own learning process but also as co-constructors of their peers’. This made peer assessment a shared responsibility for learners (Somervell, 1993) where they monitored not only the performance of others but also the meaning/content of their own oral interventions. Importantly, learners seemed to be willing to assess but at the beginning they did not feel empowered to do it:

Well, as for me, first, I feel very happy to learn about the structure to give my ideas to the other person or to the other people because before the class I did not know about the structure but I learned about the structure to write a paragraph but for me it’s is more important that I can speak better than I spoke before. So, as for me I think that I am speaking better so I am trying to do my best with the structure, I am trying to memorize the structure and use the structure for the argumentation. . . . Well, as I said, as I told you, I did not know the structure but, it is good for me to speak better so, the challenges have been looking for the words to express my ideas...words to develop my ideas. So, for me it had been good to explore more vocabulary and some expressions that you gave to us. Actually, I have tried to do this morning the assessment to my classmate but it is difficult for me because you have to listen you have to analyze you have to give your assessment to your classmate and you have to know, because you are going to give your assessment you have to know about the grammar about the correct words to speak. [sic] (Interview, Jose, Unit 1: Process regarding assessment and use of the argumentation outline)

In the account above, the learner expressed his gratitude towards the assessment outline provided. According to Jose, assessing others’ oral tasks became really challenging since he felt he needed to know more to provide meaningful comments. Peer assessment seen from the eyes of Jose was indeed a reflective learning tool (Saito, 2008), yet it required him to be more prepared when valuing others’ oral performance. Jose also suggests that there is a learning timeline as to what he could do and what he is doing now. The use of the adverb before appears to signal a change of perspective regarding his personal perception of the learning experience. It is worth mentioning that the difficulties Jose has encountered in making assessment comments may be the result of the development of a better understanding of his own critical judgment.

In Carol’s personal assessment, her learning account turned out to be informative regarding how she perceived the learning process itself.

I am...speak different in this moment because I am sure with ideas, I am sure what mistakes I have, I work in it, it is difficult because it is like a frequently mistake like a “maña” [bad habit], it is difficult that you correct himself, it is difficult, himself, because you never pay attention. I tried to record all days I read all the lesson but when speak spontaneously I forget again I need to focus attention in this. And the argumentation outline, I use it in my conversation with Indian people, I try to connect with the classes, I try to connect with the...but it is difficult because the phone conversation is difficult with the Indian person, when I think a lot, I lose the idea...now about assessment, it is useful, because you listen your voice but you do not pay attention in your mistakes, when you listen in your voice in audio you say “my voice is that” and yes it is a surprise, I think my voice is strong but my voice is soft, I am not surprised with that I am surprised with a paisa English because I am from Bogota but I have a paisa accent but I am trying to correct this because it is embarrassing for me. [sic] English have a different accent. (Interview, Carol, Unit 1: Process regarding assessment and use of the argumentation outline)

In Carol’s interview the division between before and now became recurrent. Moreover, assessment worked as a tool not only to identify linguistic difficulties but also as a learning tool for her to recognize herself as an EFL speaker. The fact that she also brought up the idea of making an attempt to improve suggests that her learning process was a personal choice that made a difference in her life (Martin, 2004).

In the other interviews, themes like attempting, now vs. before, and difficulties were also found. Nevertheless, each process and experience seemed to locate difficulties and attempts to improve within a unique personal scope.

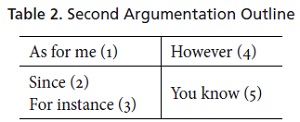

Changing Practice on the Basis of Experience

The last stage of this study was reflecting. After having observed how by means of peer assessment practices learners were able to contribute to their peers’ learning processes regarding argumentation skills, we could not help noticing that within the activities we prepared, peer assessment was limited to providing valid and meaningful comments regarding what was said in terms of language performance, not in terms of content. Moreover, we did not focus much on valuing learners’ feedback to improve the quality of our teaching. Therefore, we decided to incorporate learners’ thoughts and ideas not only regarding the argumentation outline but also in terms of how assessment should be carried out to improve their learning as well as our teaching. The emphasis here was mainly to make use of peer observations in our decision-making activity when planning lessons. This was aimed at acknowledging that in our practice there were several benefits derived from learners’ appreciations and performances. Such acknowledgement and reflection led us to make use of learners’ experiences on the matters of oral tasks to bridge them with our own pedagogical practice. Therefore, we came to the realization that we could make the argumentation outline a bit more flexible by providing learners with other expressions (see Table 2).

This new outline of argumentation posed a positive challenge to learners. They had to expand on their ideas by contrasting the argument(s) provided. The new outline allowed learners to collaborate so as to understand how to use it. In spite of being modeled by other speakers, including us (teachers), it was still puzzling for some learners. Some were able to use it upon the first attempt but others needed to be exposed to it for a longer period of time. Although learners were able to use it in the end, it was evident that the assessment received from peers was again essential to learn to handle the new outline.

Conclusion

According to the results of the study, peer assessment seems to be a key component when improving argumentation skills in the EFL classroom. Assessment had a bearing on how learners constructed oral practices around the discussion of different topics. Whilst learners used peer assessment as a strategy to reflect upon their practices (Cheng & Warren, 1999), such engagement unveiled that the more assessment there was on oral tasks the more critical they became regarding their own argumentative skills. Learners were able to choose a personal path to set action plans when difficulties regarding their abilities were spotted, and they also collaborated among themselves, suggesting and giving opinions so that action plans could be discussed and integrated into further actions, such as how to complete a task (Beatty, 2003).

It is important to pinpoint here that the findings suggest that learners became engaged in a kind of self-directed learning, defined as “a process in which individuals take the initiative, with or without the help of others, in diagnosing their learning needs, formulating learning goals, identifying human and material resources for learning, choosing and implementing learning strategies, and evaluating learning outcomes” (Knowles, 1975, p. 18). Self-directed learning promotes learner agency, which refers to “the capability of individual human beings to make choices and act on these choices in a way that makes a difference in their lives” (Martin, 2004, p. 135). As such, learners appear to have acted within the possibilities afforded by the social structures in which they were situated (Miller, 2003).

The above considerations relate to the concept of autonomy. During the process of the learning and teaching carried out in this study, both the learners and we as teachers were engaged in promoting a more autonomous and reflective process regarding argumentation skills and peer assessment practices. Autonomy can be defined as “the competence to develop as a self-determined, socially responsible, and critically aware participant in (and beyond) educational environments, within a vision of education as (inter) personal empowerment and social transformation” (Jiménez Raya, Lamb, & Vieira, 2007, p. 1). This notion can shed some light onto how learners developed a critical stance when assessing others. This critical stance moved beyond the mere correction of linguistic features into a more personal empowerment. Learners acted as co-constructors of knowledge produced through the assessment of oral tasks. Arguably, these served to open up a space for learners to exercise their agency as language learners, which means that they performed as language learners and language users within the possibilities afforded within the classroom in order to claim control of their learning processes (van Lier, 2008). Nonetheless, what this study really brought forth was the idea that the learning experience is pivotal for the creation of any knowledge, since experience is the basis for reflection and agency.

1All students’ names are either fictional or labeled as S# to protect their identities.

References

Al-Barakat, A., & Al-Hassan, O. (2009). Peer assessment as a learning tool for enhancing student teachers’ preparation. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 37(4), 399-413. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598660903247676.

Bachman, L. F. (1990). Fundamental considerations in language testing. Reading, UK: Addison Wesley.

Baynham, M. (1995). Literacy practices: Investigating literacy in social contexts. London, UK: Longman.

Beatty, K. (2003). Teaching and researching: Computer assisted language learning. London, UK: Longman.

Bell, J. (1999). Doing your research project: A guide for first-time researchers in education, health and social sciences. Philadelphia, PA: Open University Press.

Bell, P., & Linn, M. (2000). Scientific arguments as learning artifacts: Designing for learning from the web with KIE. International Journal of Science Education, 22(8), 797-817. https://doi.org/10.1080/095006900412284.

Black, P., Harrison, C., Lee, C., Marshall, B., & Wiliam, D. (2003). Assessment for learning: Putting it into practice. New York, NY: Open University Press.

Brown, H. D. (2004). Language assessment: Principles and classroom practice. New York, NY: Longman.

Brown, J. D. (1998). New ways of classroom assessment. Alexandria, VA: TESOL.

Chastain, K. (1998). Developing second-language skills: Theory to practice. Chicago, IL: Harcourt Brace Publishers.

Cheng, W., & Warren, M. (1999). Peer and teacher assessment of the oral and written tasks of a group project. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 24(3), 301-314. https://doi.org/10.1080/0260293990240304.

Cheng, W., & Warren, M. (2005). Peer assessment of oral proficiency. Language Testing, 22(1), 93-121. https://doi.org/10.1191/0265532205lt298oa.

Cohen, A. D. (1994). Assessing language ability in the classroom. Boston, MA: Heinle and Heinle.

Crisp, G. (2007). The e-assessment handbook. London, UK: Continuum.

Davies, P. (2006). Peer assessment: Judging the quality of students’ work by comments rather than marks. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 43(1), 69-82. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703290500467566.

Deane, P., & Song, Y. (2014). A case study in principled assessment design: Designing assessments to measure and support the development of argumentative reading and writing skills. Psicología Educativa, 20(2), 99-108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pse.2014.05.006.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. New York, NY: Kappa Delta Pi.

Donaldson, A. J. M., Topping, K. J., & Aitchison, R. (1996). Promoting peer assisted learning amongst students in higher and further education. Birmingham, UK: SEDA.

Freeman, M. (1995). Peer assessment by groups of group work. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 20(3), 289-300. https://doi.org/10.1080/0260293950200305.

Hartley, J. (1998). Learning and studying: A research perspective. London, UK: Routledge.

Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277-1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

Hymes, D. (1972). On communicative competence. In J. B. Pride & J. Homes (Eds.), Sociolinguistics: Selected readings (pp. 269-293). Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books.

Jiménez Raya, M., Lamb, T., & Vieira, F. (2007). Pedagogy for autonomy in language education in Europe: Towards a framework for learner and teacher development. Dublin, IE: Authentik.

Keppell, M., & Carless, D. (2006). Learning-oriented assessment: A technology-based case study. Assessment in Education, 13(2), 179-191. https://doi.org/10.1080/09695940600703944.

Knowles, M. S. (1975). Self-directed learning: A guide for learners and teachers. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall/Cambridge.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Kuhn, D., & Crowell, A. (2011). Dialogic argumentation as a vehicle for developing young adolescents’ thinking. Psychological Science, 22(4), 545-552. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611402512.

Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2009). InterViews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Lew, M. D. N., Alwis, W. A. M., & Schmidt, H. G. (2010). Accuracy of students’ self-assessment and their beliefs about its utility. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(2), 135-156. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930802687737.

Martin, J. (2004). Self-regulated learning, social cognitive theory, and agency. Educational Psychologist, 39(2), 135-145. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3902_4.

McDowell, L. (1995). The impact of innovative assessment on student learning. Innovation in Education and Training International, 32(4), 302-313. https://doi.org/10.1080/1355800950320402.

Mello, J. A., (1993). Improving individual member accountability in small work group settings. Journal of Management Education, 17(2), 253-259. https://doi.org/10.1177/105256299301700210.

Mercer, N., & Littleton, K. (2007). Dialogue and development of children’s thinking: A sociocultural approach. London, UK: Routledge.

Mercier, H. (2011). Reasoning serves argumentation in children. Cognitive Development, 26(3), 177-191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogdev.2010.12.001.

Miller, J. (2003). Audible difference: ESL and social identity in schools. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Murrell, P. C., Jr. (2000). Community teachers: A conceptual framework for preparing exemplary urban teachers. The Journal of Negro Education, 69(4), 338-348. https://doi.org/10.2307/2696249.

Newby, P. (2010). Research methods for education. Essex, UK: Pearson.

Nilson, L. B. (2003). Improving student peer feedback. College Teaching, 51(1), 34-38. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567550309596408.

Nussbaum, E. M., & Sinatra, G. M. (2003). Argument and conceptual engagement. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 28(3), 384-395. doi: 10.1016/S0361-476X(02)00038-3.

Olsen, R. E. W. B., & Kagan, S. (1992). About cooperative learning. In C. Kessler (Ed.), Cooperative language learning: A teacher’s resource book (pp. 1-30). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

O’Malley, J. M., & Valdez Pierce, L. (1996). Authentic assessment for English language learners: Practical approaches for teachers. New York, NY: Addison Wesley.

Powers, B. A., & Knapp, T. R. (2006). Dictionary of nursing theory and research. New York, NY: Springer.

Saito, H. (2008). EFL classroom peer assessment: Training effects on rating and commenting. Language Testing, 25(4), 553-581. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532208094276.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Shaaban, K. (2005). Assessment of young learners. English Teaching Forum, 43(1), 34-40.

Skehan, P. (1998). A cognitive approach to language learning. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Somervell, H. (1993). Issues in assessment, enterprise and higher education: The case for self-, peer and collaborative assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 18(3), 221-233. https://doi.org/10.1080/0260293930180306.

Taras, M. (2010). Student self-assessment: Processes and consequences. Teaching in Higher Education, 15(2), 199-209. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562511003620027.

Topping, K. J., Smith, E. F., Swanson, I., & Elliot, A. (2000). Formative peer assessment of academic writing between postgraduate students. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 25(2), 149-169. https://doi.org/10.1080/713611428.

van den Berg, I., Admiraal, W., & Pilot, A. (2006). Designing student peer assessment in higher education: Analysis of written and oral peer feedback. Teaching in Higher Education, 11(2), 135-147. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510500527685.

van Eemeren, F. H., Grootendorst, R., & Henkemans, F. S. (1996). Fundamentals of argumentation theory: A handbook of historical backgrounds and contemporary developments. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

van Lier, L. (2008). Agency in the classroom. In J. P. Lantolf & M. E. Poehner (Eds.), Sociocultural theory and the teaching of second languages (pp. 163-186). London, UK: Equinox.

Wells, G. (1987). The meaning makers: Children learning language and using language to learn. London, UK: Hodder & Stoughton.

Widdowson, H. G. (1978). Teaching language as communication. London, UK: Oxford University Press.

About the Authors

Diego Fernando Ubaque Casallas works for the Centro Cultural Colombo Americano and Pontificia Universidad Javeriana (Colombia) as an EFL teacher. He holds an MA in applied linguistics to the teaching of English from Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas (Colombia).

Freddy Samir Pinilla Castellanos works for the Centro Cultural Colombo Americano (Bogotá) as an EFL teacher. He holds a Bachelor’s degree in education from the University of South Carolina (USA). His research interests have to do with assessment practices in the EFL classroom.

References

Al-Barakat, A., & Al-Hassan, O. (2009). Peer assessment as a learning tool for enhancing student teachers’ preparation. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 37(4), 399-413. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13598660903247676.

Bachman, L. F. (1990). Fundamental considerations in language testing. Reading, UK: Addison Wesley.

Baynham, M. (1995). Literacy practices: Investigating literacy in social contexts. London, UK: Longman.

Beatty, K. (2003). Teaching and researching: Computer assisted language learning. London, UK: Longman.

Bell, J. (1999). Doing your research project: A guide for first-time researchers in education, health and social sciences. Philadelphia, PA: Open University Press.

Bell, P., & Linn, M. (2000). Scientific arguments as learning artifacts: Designing for learning from the web with KIE. International Journal of Science Education, 22(8), 797-817. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/095006900412284.

Black, P., Harrison, C., Lee, C., Marshall, B., & Wiliam, D. (2003). Assessment for learning: Putting it into practice. New York, NY: Open University Press.

Brown, H. D. (2004). Language assessment: Principles and classroom practice. New York, NY: Longman.

Brown, J. D. (1998). New ways of classroom assessment. Alexandria, VA: TESOL.

Chastain, K. (1998). Developing second-language skills: Theory to practice. Chicago, IL: Harcourt Brace Publishers.

Cheng, W., & Warren, M. (1999). Peer and teacher assessment of the oral and written tasks of a group project. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 24(3), 301-314. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0260293990240304.

Cheng, W., & Warren, M. (2005). Peer assessment of oral proficiency. Language Testing, 22(1), 93-121. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/0265532205lt298oa.

Cohen, A. D. (1994). Assessing language ability in the classroom. Boston, MA: Heinle and Heinle.

Crisp, G. (2007). The e-assessment handbook. London, UK: Continuum.

Davies, P. (2006). Peer assessment: Judging the quality of students’ work by comments rather than marks. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 43(1), 69-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14703290500467566.

Deane, P., & Song, Y. (2014). A case study in principled assessment design: Designing assessments to measure and support the development of argumentative reading and writing skills. Psicología Educativa, 20(2), 99-108. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pse.2014.05.006.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. New York, NY: Kappa Delta Pi.

Donaldson, A. J. M., Topping, K. J., & Aitchison, R. (1996). Promoting peer assisted learning amongst students in higher and further education. Birmingham, UK: SEDA.

Freeman, M. (1995). Peer assessment by groups of group work. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 20(3), 289-300. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0260293950200305.

Hartley, J. (1998). Learning and studying: A research perspective. London, UK: Routledge.

Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277-1288. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

Hymes, D. (1972). On communicative competence. In J. B. Pride & J. Homes (Eds.), Sociolinguistics: Selected readings (pp. 269-293). Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books.

Jiménez Raya, M., Lamb, T., & Vieira, F. (2007). Pedagogy for autonomy in language education in Europe: Towards a framework for learner and teacher development. Dublin, IE: Authentik.

Keppell, M., & Carless, D. (2006). Learning-oriented assessment: A technology-based case study. Assessment in Education, 13(2), 179-191. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09695940600703944.

Knowles, M. S. (1975). Self-directed learning: A guide for learners and teachers. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall/Cambridge.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Kuhn, D., & Crowell, A. (2011). Dialogic argumentation as a vehicle for developing young adolescents’ thinking. Psychological Science, 22(4), 545-552. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0956797611402512.

Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2009). InterViews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Lew, M. D. N., Alwis, W. A. M., & Schmidt, H. G. (2010). Accuracy of students’ self-assessment and their beliefs about its utility. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(2), 135-156. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602930802687737.

Martin, J. (2004). Self-regulated learning, social cognitive theory, and agency. Educational Psychologist, 39(2), 135-145. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3902_4.

McDowell, L. (1995). The impact of innovative assessment on student learning. Innovation in Education and Training International, 32(4), 302-313. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1355800950320402.

Mello, J. A., (1993). Improving individual member accountability in small work group settings. Journal of Management Education, 17(2), 253-259. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/105256299301700210.

Mercer, N., & Littleton, K. (2007). Dialogue and development of children’s thinking: A sociocultural approach. London, UK: Routledge.

Mercier, H. (2011). Reasoning serves argumentation in children. Cognitive Development, 26(3), 177-191. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cogdev.2010.12.001.

Miller, J. (2003). Audible difference: ESL and social identity in schools. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Murrell, P. C., Jr. (2000). Community teachers: A conceptual framework for preparing exemplary urban teachers. The Journal of Negro Education, 69(4), 338-348. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2696249.

Newby, P. (2010). Research methods for education. Essex, UK: Pearson.

Nilson, L. B. (2003). Improving student peer feedback. College Teaching, 51(1), 34-38. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/87567550309596408.

Nussbaum, E. M., & Sinatra, G. M. (2003). Argument and conceptual engagement. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 28(3), 384-395. doi: 10.1016/S0361-476X(02)00038-3.

Olsen, R. E. W. B., & Kagan, S. (1992). About cooperative learning. In C. Kessler (Ed.), Cooperative language learning: A teacher’s resource book (pp. 1-30). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

O’Malley, J. M., & Valdez Pierce, L. (1996). Authentic assessment for English language learners: Practical approaches for teachers. New York, NY: Addison Wesley.

Powers, B. A., & Knapp, T. R. (2006). Dictionary of nursing theory and research. New York, NY: Springer.

Saito, H. (2008). EFL classroom peer assessment: Training effects on rating and commenting. Language Testing, 25(4), 553-581. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0265532208094276.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Shaaban, K. (2005). Assessment of young learners. English Teaching Forum, 43(1), 34-40.

Skehan, P. (1998). A cognitive approach to language learning. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Somervell, H. (1993). Issues in assessment, enterprise and higher education: The case for self-, peer and collaborative assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 18(3), 221-233. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0260293930180306.

Taras, M. (2010). Student self-assessment: Processes and consequences. Teaching in Higher Education, 15(2), 199-209. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13562511003620027.

Topping, K. J., Smith, E. F., Swanson, I., & Elliot, A. (2000). Formative peer assessment of academic writing between postgraduate students. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 25(2), 149-169. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/713611428.

van den Berg, I., Admiraal, W., & Pilot, A. (2006). Designing student peer assessment in higher education: Analysis of written and oral peer feedback. Teaching in Higher Education, 11(2), 135-147. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13562510500527685.

van Eemeren, F. H., Grootendorst, R., & Henkemans, F. S. (1996). Fundamentals of argumentation theory: A handbook of historical backgrounds and contemporary developments. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

van Lier, L. (2008). Agency in the classroom. In J. P. Lantolf & M. E. Poehner (Eds.), Sociocultural theory and the teaching of second languages (pp. 163-186). London, UK: Equinox.

Wells, G. (1987). The meaning makers: Children learning language and using language to learn. London, UK: Hodder & Stoughton.

Widdowson, H. G. (1978). Teaching language as communication. London, UK: Oxford University Press.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Fatma Şeyma Koç, Funda Ölmez-Çağlar. (2023). Global Perspectives on Effective Assessment in English Language Teaching. Advances in Educational Technologies and Instructional Design. , p.235. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-6684-8213-1.ch008.

2. Sonia Patricia Hernandez-Ocampo. (2022). Colombian Scholars’ Discussion About Language Assessment: A Review of Five Journals. Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 24(2), p.231. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v24n2.94468.

3. I Gede Ratnaya. (2023). Measuring Learning Discipline with Peer Group Assessment of Engineering Vocational High School Students in Bali Province. Journal for Lesson and Learning Studies, 6(1), p.18. https://doi.org/10.23887/jlls.v6i1.59730.

4. Gülcan CANBOLAT, Ercan TOP. (2020). USE OF THREADED DISCUSSION IN BLOG ENVIRONMENT WITH RESPECT TO FACTORS AFFECTING STUDENTS’ COURSE SATISFACTION. Abant İzzet Baysal Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 20(1), p.605. https://doi.org/10.17240/aibuefd.2020.20.52925-637633.

5. Beyza Uçar, Yasemin Demiraslan Çevik. (2021). The Effect of Argument Mapping Supported with Peer Feedback on Pre-Service Teachers' Argumentation Skills. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 37(1), p.6. https://doi.org/10.1080/21532974.2020.1815107.

6. Katherin Pérez-Rojas, Carolina Herrera Carvajal. (2024). Current Status of English as a Foreign Language Evaluation in Colombia. Cuadernos de Lingüística Hispánica, (43), p.1. https://doi.org/10.19053/uptc.0121053X.n43.2024.16675.

7. Entika Fani Prastikawati, Moses Adeleke Adeoye. (2024). Enhancing Learning: Peer Assessment's Influence on English as a Foreign Language Education in Indonesia. Mimbar Ilmu, 29(2), p.246. https://doi.org/10.23887/mi.v29i2.77097.

8. Emi Gustina, Viyanti Viyanti, Kartini Herlina. (2025). A need analysis for developing multi-representation assessment instruments assisted by Thunkable to measure argumentation skills in fluid materials. Indonesian Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 8(2), p.502. https://doi.org/10.24042/bb6k5224.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.