Critical Incidents of Transnational Student-Teachers in Central Mexico

Incidentes críticos de profesores de inglés transnacionales en formación en el Centro de México

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v20n1.62860Keywords:

Critical incidents, in-service teachers, identity, narratives, transnational (en)identidad, incidentes críticos, narrativas, profesores en servicio, transnacional (es)

Critical Incidents of Transnational Student-Teachers in Central Mexico

Incidentes críticos de profesores de inglés transnacionales en formación en el Centro de México

José Irineo Omar Serna-Gutiérrez*

Irasema Mora-Pablo**

Universidad de Guanajuato, Guanajuato, Mexico

*sernaomar@ugto.mx

**imora@ugto.mx

This article was received on February 22, 2017, and accepted on August 25, 2017.

How to cite this article (APA, 6th ed.):

Serna-Gutiérrez, J. I. O., & Mora-Pablo, I. (2018). Critical incidents of transnational student-teachers in Central Mexico. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 20(1), 137-150. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v20n1.62860.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This study is an exploration of the life-changing decisions and changes which the participants underwent, and which led them to pursue an education in English language teaching (or languages). The foremost objective of this study was to highlight the critical incidents from the past, present, and teaching practice of transnational students in a BA in TESOL program who are also English teachers in central Mexico. Through a narrative analysis, critical incidents in the lives of transnational student/teachers were identified. The findings of this research showed how the participants could explore their identity formation process through the critical incidents.

Key words: Critical incidents, in-service teachers, identity, narratives, transnational.

Este estudio marca, por lo tanto, una exploración de las decisiones que tomaron los participantes y que cambiaron o influyeron en su decisión de continuar con una carrera en enseñanza del inglés (o de lenguas). El objetivo principal de este estudio fue resaltar los incidentes críticos por los que han pasado profesores de inglés transnacionales, en el pasado, presente y durante su práctica docente actual. A través de un análisis narrativo, se identificaron varios incidentes críticos en la vida de los maestros-estudiantes transnacionales. Los resultados de esta investigación mostraron cómo a partir de incidentes críticos, los participantes pudieron explorar su formación de identidad personal y profesional.

Palabras clave: identidad, incidentes críticos, narrativas, profesores en servicio, transnacional.

Introduction

This paper aims to explore the critical incidents before and during the BA in TESOL program (teaching English to speakers of other languages) of a group of in-service transnational teachers in a public university in central Mexico and the impact on their teaching practice. The study is qualitative in nature and follows a narrative methodology. Through narrative data collection techniques, critical incidents were identified. This study is part of a larger scale project funded by the Secretariat of Public Education (SEP) through the Program for Professional Teacher Development (PRODEP) in which three universities; Universidad de Guanajuato, Universidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas, and the University of Texas at San Antonio, collaborated.

Background

Our motivation to explore the lives of transnational students comes from the background of one of the authors. He lived in the us for the first twenty years of his life, always having constant contact with Mexico. His family and he would travel to Mexico almost every year to spend the winter holidays with family; it was a meeting point for all of the family. This movement between the two nations shaped his identity over time, and influenced his interest in studying this phenomenon of transnationalism.

Based on these personal experiences, transnationals who participated in this study underwent a molding of identity through their constant movement between the US and Mexico. This movement leads to what is known as critical incidents. The concept of critical incidents arose in this study after the data analysis. We noticed that the participants had pivotal moments in their lives that led them toward English language teaching. We decided to use the term critical incidents after learning about this idea in a course of the BA in TESOL program.

Literature Review

Critical Incidents

Historically, the analysis of critical incidents has been used in fields such as psychology and education. Flanagan (1954) coined the term critical incident technique (CIT) and used it to conduct “direct observations of human behavior in such a way as to facilitate their potential usefulness in solving practical problems and developing broad psychological principles” (p. 327).

Scholars interested in critical incident analysis have a broad spectrum of definitions in regard to the breadth of the term. For example, Measor (as cited in Rolls & Plauborg, 2009) defines critical incidents as part of critical phases. These critical phases can be categorized into three types: (1) extrinsic critical phases, (2) personal critical phases, and (3) intrinsic critical phases. Extrinsic critical phases are related to external factors affecting the critical incidents, such as, sociocultural or sociohistorical factors in the context of the participants. Personal critical phases arise from major changes in the participants’ personal lives, such as marriage, divorce, childbirth, or death of a relative. Intrinsic critical phases are periods where the participants were faced with important decisions in their professional lives, or in this case, important decisions regarding their choice to study for a BA in TESOL (Rolls & Plauborg, 2009).

A further explanation of critical phases provided by Sikes, Measor, and Woods (2001) is that critical phases are longer periods of time in which critical incidents take place. The different circumstances surrounding the three critical phases that we mentioned before were the catalyst for the critical incidents that were discovered and interpreted by both we and the participants.

Tripp (2012) provides a definition of critical incidents as being “events or situations which mark a significant turning-point or change in the life of a person” (p. 24). The critical incidents in this project were significant not only in the description of the event, but also in its cause and result. Tripp explains that we have not only to describe what happened, but also to determine what caused the incident to happen.

The theory behind the interpretation of critical incidents implies that “their [critical incidents] criticality is based on the justification, the significance, and the meaning given to them” (Angelides, 2001, p. 431). Meaning that as researchers, we must justify our interpretation of the critical incident by proving its significance and meaning. This is achieved by a reciprocal process of reflection between the researcher and the participants in the data collection stages, and more specifically in the e-mail interviews.

Schon (as cited in Angelides, 2001) states that “when an incident that surprises the researcher occurs, it becomes the stimulus for reflection, and this reflection leads to the decision about the incident’s criticality” (p. 431). The stimulus arose from the identification of specific situations in which the participants experienced a change that influenced their decisions to enroll in the BA in TESOL program and to become English teachers.

Transnationals Becoming Professionals

Authors have used different terminology to label transnationals. Some, such as Zuñiga and Hammann (2009), have used the term “sojourner” to describe those who do not have plans of staying in a permanent location as immigrants. Perhaps a more exact way to address these transnationals is as Moctezuma (2008) calls collective transnational migrants. Moctezuma defines a collective transnational migrant as:

the organized migrant who has a certain level of association; a type of organization, therefore, superior to that of migrant networks or clubs. At the same time, it refers to formal, permanent organizational structures with negotiating capabilities vis-à-vis the state and binational recognition. (p. 93)

Trueba (2004) expands on the definition and states that transnationalism implies the development of “transnational identities” and “social relations”, which implies that transnational families undergo particular experiences. In Jerdee’s (2010) research she discusses a trait of these transnational families as follows:

When these families return to Mexico for extended visits or permanent stays, their children, who have always identified themselves as “Mexican,” lack the knowledge and language skills necessary to navigate the Mexican school system. (p. 2)

In the case of the students in this study, they are all members of a formal and permanent organization, which in this case is the BA in TESOL program they study in in central Mexico. Not only do they share this community, but they also share other communities outside of the BA program, such as being members of the TESOL community. In addition, they all have ties with family and friends in the US. Membership in these different communities creates social relations and these can lead to critical incidents. These incidents can be reflected in their choice to become English language teachers (ELTs). It was due to this factor, in combination with others, that students had a hard time adapting to the education system when they returned to Mexico and found refuge in the BA in TESOL program. However, it is noticeable that as they progressed through the BA program, they found a place where they could see themselves develop as professionals in the future.

Professional Identity

Norton and Toohey (2011) in their post-structuralist view, define identity as “fluid, context-dependent, and context-producing, in particular historical and cultural circumstances” (p. 419). Identity can be defined as individuals’ “concepts” or “images” of themselves. For the formation of a professional identity, these “concepts” and “images” develop in the training stage and are influenced directly by their teaching practice. (Kumpusalo et al., 1994, p. 70)

In the description of identity, many models exist for describing it. One model proposes that “the identification of an individual requires the consistent circulation of certain signs of identity and certain metapragmatic models through events that include, refer to or presuppose that individual (Wortham, 2006, p. 38).

The signs of identity mentioned by Wortham (2006) in this study are found throughout the critical incidents described by the participants. These signs of identity all delineate the participants’ transnational identity, and later their professional identity.

Authors such as Clarke, Hyde, and Drennan (2013) define professional identity as a continuous process of interpreting and re-interpreting experiences. Through the ongoing analysis of critical incidents, participants in this study were able to interpret and re-interpret their professional identity. Also, participants discuss where they see themselves in the future within TESOL. For the previous, Beijaard (as cited in Clarke et al., 2013) states that this continuous process “does not answer the question of whom I am at the moment but who I want to become” (p. 9). Through the different data collected the participants describe different contexts in which their professional identity is shaped and transformed. These different contexts along with the change in time molded the participants’ professional identity.

Professional identity or teacher identity is described by Bullough as the beliefs teachers have regarding teaching and learning and on which they base their teaching decisions (as cited in Beijaard, Meijer, & Verloop, 2004). The critical incidents connected to professional identity explored in this study, in many ways, represent previous beliefs held about language teaching and how those beliefs were modified after the incident.

Research Questions and Objective

This study explores critical incidents of transnational student-teachers throughout different stages of their lives. “As human beings, we are creating narratives as we live our lives” (Watkins-Goffman, 2006, p. 6). This progression in the life of transnational student-teachers brought about the research questions of this study, which are: (1) What are the critical incidents of transnational students before participation in the BA in TESOL program? (2) What are the critical incidents during the BA in TESOL program of transnational students? and (3) What are the critical incidents of transnational students in their teaching practice?

Through this exploration or as it is known in narrative research “narrative knowledging” (Barkhuizen, 2011, p. 395), we have been able to identify critical incidents. After “narrative knowledging” took place, the foremost goal of the research project was/is to explore critical incidents of transnational students.

Narrative Inquiry

This study was qualitative in nature. The methodology chosen for this study is narrative inquiry or analysis. Narrative inquiry and its data collection tools, according to Flick (2006, p. 23), focus on biographical experiences, but larger topics and contexts are also studied. This study explores specific types of experiences; those of transnational students, and a specific context; transnational students in Mexico studying for a BA in TESOL. The biographical experiences that are studied are the critical incidents that the transnational participants underwent before and during their BA studies, and in their teaching practice.

Narrative inquiry was adopted for this research to tell the stories of the participants. This methodology emphasizes “what people’s stories are about” (Chase, 2011, p. 421) through a negotiation process between the participant and the researcher. This is known as “narrative dialogue” (Barkhuizen, 2011, p. 394), which is a reflective practice that makes meaning of their experiences.

Narrative inquiry has several characteristics, as listed by Ospina and Dodge (2005):

(1) [narratives] are accounts of characters and selective events occurring over time, with a beginning, a middle, and an end; (2) they are retrospective interpretations of sequential events from a certain point of view; (3) they focus on human intention and action—those of the narrator and others; (4) they are part of the process of constructing identity (the self in relation to others); (5) they are coauthored by narrator and audience. (pp. 144-145)

Collection Techniques

As we defined the data collection tools, we realized that we needed to involve our participants in this process. As Mora Pablo (2014) explains, “the qualitative researcher is led by his or her data in different directions to the ones initially anticipated and will often have to bring in during the research process other techniques for data collection or corroboration” (p. 41).

The techniques for data collection included a range of narrative strategies: (1) autobiographies, (2) semi-structured interviews, and (3) e-mail interviews. The first stage of the data collection was to gather and analyze autobiographies provided by the participants. After the autobiographies were analyzed, semi-structured interviews were conducted as a means to expand on the data gathered in the autobiographies. Lastly, an e-mail interview was conducted to focus on the critical incidents discovered in both the autobiographies and the semi-structured interviews. Table 1 outlines the data collection techniques employed along with a description of how they were utilized within this study.

Denscombe (2007, p. 288) describes these stages of analysis as an “iterative”, non-linear process consisting of five stages: (1) preparation of the data (i.e., reading and transcribing interviews), (2) familiarity with the data (i.e., identifying occurrences of critical incidents), (3) interpreting the data (i.e., making connections with literature and data), (4) verifying the data (i.e., going back to the interviews and contacting participants for clarification if necessary), and (5) representing the data.

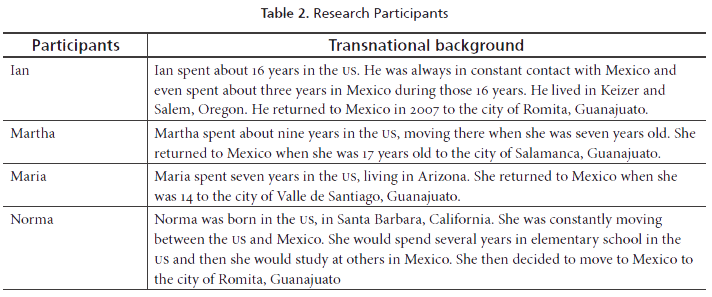

Participants

The participants of this study were all students in a BA in TESOL program at Universidad de Guanajuato (Guanajuato campus) and also in-service teachers at different institutions in the state of Guanajuato. Participants were within the 19-25 age group and three females and one male were selected. However, the determining factor for their selection was their transnational background. Table 2 presents each participant along with such background.

Ethics

According to Christians (2011), there are two necessary conditions when giving participant informed consent. The first is that participants voluntarily participate without any forceful action from the researcher. Following this advice, participants were given a consent form informing them of the nature of this study. To protect the integrity of the participants, they were given pseudonyms.

Data Analysis and Findings

The critical events in this study are organized according to temporality. Clandinin, Pushor, and Orr (2007) describe temporality as being a part of the common places of narrative inquiry. According to those authors, temporality can be understood in the following terms: “events and people always have a past, present, and a future. In narrative inquiry it is important to always try to understand people, places, and events as in process, as always in transition” (p. 23).

Through a careful analysis, it was found that the critical incidents which were identified occurred at three different moments in the participants’ lives: before they entered the ba TESOL program, during the BA program, and during their teaching practice.

Before Entering the BA in TESOL Program

Before entering the BA in TESOL program, these participants underwent a series of stages where they discovered that the BA in TESOL program was the right decision for them. The critical incidents that led to their decision of enrolling in the BA program were different, having only the final result in common. These pre-BA program critical incidents are analyzed as what Tripp (2012) describes as asking both what happened and how it happened, which lead to a description of the deeper structures of how the incident occurred.

For some transnationals, their motivation to seek out ELT comes from an influential person in their lives who noticed something in them and advised them to pursue teaching. In Ian’s case, a teacher at his high school in Romita, Guanajuato, noticed personal qualities in him with potential to be a teacher as well as his linguistic capital.

The teacher let me know that he had heard good things about my English and how I helped my classmates and mainly my teachers. I had a close relationship with this teacher and we got along well, so his advice for me to become an English teacher was taken very personal. Since he gave me the advice to become an English teacher, it is something that I had in mind always thinking about how it happened that he advised me to become an English teacher. (Ian, e-mail interview)

Ian’s experience is an example of what others notice in transnational students. They stand out because of their linguistic capital and in Ian’s case his personal qualities of helping others. Linguistic capital comes from Bourdieu’s notion of cultural capital (as cited in Morrison & Lui, 2000). Linguistic capital is defined by Morrison and Lui (2000) as “fluency in, and comfort with, a high-status, world-wide language which is used by groups who possess economic, social, cultural, and political power and status in local society and global society” (p. 473). They further explain that students who “possess [linguistic capital], have access to, or develop linguistic capital, thereby have access to better life chances” (Morison & Lui, 2000, p. 473). Ian’s ability to help others was a signal for his teacher that he should take on the teaching profession. He takes this advice to heart and follows through.

For others, the decision to enter the BA TESOL program arises out of an unexpected “plan b”. As in Martha’s case, where her initial plan was to study psychology but because she suffered problems with the admissions exam she could not enter the program. This critical phase can be described as what Measor (as cited in Rolls & Plauborg, 2009) calls an “extrinsic critical phase”, as external factors influenced her decision to seek an alternative.

My first try at an admission exam was negative. I needed more knowledge about what is studied here in Mexico. (Martha, autobiography)

Her poor performance on the exam pushed her to seek out an alternative as one of the main reasons for returning to Mexico was to obtain a university education. As Jerdee (2010) discusses, when transnational students return to Mexico, they “lack knowledge and language skills necessary to navigate the Mexican school system” (p. 2). Like many other transnationals who return in hopes of getting an education, they encounter critical incidents in which they must take an alternative route. In the case of Martha, the alternative route is an education in TESOL.

Sometimes, the decision to take the route in TESOL comes from an early age while learning the language due to the circumstances of living in what can be seen as a foreign culture. In Maria’s case, her struggle with the language can be interpreted within Measor’s “personal critical phase” (as cited in Rolls & Plauborg, 2009), as it would later lead her toward a life changing decision.

Now that I think about it, being an English teacher interested me a lot. I could remember how bad it felt not to understand others, and for that reason I decided to help others learn English. (Maria, autobiography)

Later she expands and describes a specific critical incident from her language learning experience. This incident occurred at her elementary school in the us during a classroom game:

I remember when I was in my second-grade class, which was the year I actually started to learn and use the language . . . When I won one [the teacher] only had chocolates and lollipops. [She] asked me, “What you want: A chocolate or a lollipop?” So I said “a popsicle”. My classmates laughed in my face and said, “It’s not a ‘popsicle’ it’s a lollipop”. I remember I felt very embarrassed and like they all hated me . . . I guess I just did not want others to feel left out in situations just because of their language barriers. (Maria, e-mail interview)

Maria describes an incident when she made a mistake and used the wrong word for lollipop. At first it seems like a trivial mistake, to confuse “popsicle” with “lollipop”, but the emotional impact that it had on her was much greater. Incidents such as these, where there are “language barriers” in transnationals’ communication can be seen as critical incidents of “anxiety and tension” (Sikes et al., 2001, p. 104). These feelings of “anxiety and tension” later served as motivational factors for her to pursue a BA degree in TESOL as she explains above.

The previous participants underwent critical incidents in their early education that in one way or another influenced their decisions to become English teachers. For Norma, this decision arose through a series of events. This series of events can be described as Measor’s “intrinsic critical phases” (as cited in Rolls & Plauborg, 2009) because she was faced with an important decision regarding her professional and academic life. Her journey began while studying English at a language school and studying a different major. At that time, she had been studying psychology, but an interest in TESOL began to grow and it was probably her English lessons that planted the seed.

I was impressed by their way of teaching. I truly fell in love with those teachers. They are perfect teachers in my eyes. (Norma, e-mail interview)

Her positive experience with those teachers while studying English at the Language Department of Universidad de Guanajuato led her to question if she was doing the right thing. She discovers that it was not beneficial for her to continue with psychology and began to look for other options.

When I entered psychology, I was sure that it was the right decision. Then while in the BA [psychology] I discovered that it wasn’t. I just didn’t want [ELT] to go wrong again. (Norma, e-mail interview)

The previous comment came after she was asked why she decided to study a certification course in language teaching before studying for the BA in TESOL. She explains that before she entered the BA in TESOL program, she wanted to make sure it was the right decision for her. Luckily, her experience in the diplomado was positive and soon after she enrolled in the BA program.

These critical incidents took place before the participants decided to enroll in the BA in TESOL. They are part of different critical phases that led them to make life-changing decisions. The final result is the same; however, the events that led them to make a decision would later shape their professional identity in many different ways.

To many, these incidents at first glance may seem insignificant and meaningless. As Tripp (2012) puts it, critical incidents at first may appear “typical rather than critical” (p. 25). However, in the same sentence he states that these “typical” incidents become critical only after analysis of the incidents takes place.

Ian, Maria, Martha, and Norma all narrated critical incidents which occurred before entering the BA program that in one way or another led them to choose a path in TESOL. These incidents began as early as childhood when learning the English language, and all the way up to adulthood by helping others learn the language in high school.

During the BA Program

Once the participants decided to enroll in the BA program in TESOL, they went through another set of critical incidents. The role of these critical incidents during the BA program later demonstrated to be of great importance, as they had a direct impact on their professional identity.

For students such as Martha the BA program brought many changes to their lives. One of the most significant consequences of enrolling in the BA program was that it pushed her toward a job in ELT.

At the moment which I was told that I needed a job I was in shock because it was never in my plan to become a teacher. Unfortunately, at that specific moment I was going through a lot of economic problems so I really did not have an option but to get the job. I also thought about quitting the BA because I did not consider myself capable of giving a class. I did not consider myself prepared for that. (Martha, e-mail interview)

When Martha enrolled in the BA program, she was not aware that having a teaching job was an important part of the program. Not only was it a requirement for the program, but she also needed to teach due to economic reasons. Both of those reasons motivated her despite her feeling unprepared. She was forced to make a decision that would determine her academic and professional life, thus, this can be identified as an “intrinsic critical phase” (Measor as cited in Rolls & Plauborg, 2009). Not only did she begin to teach, but was also able to figure herself out as a professional. Before entering the BA program, she simply wanted to study for the sake of studying. She did not have a clear vision of her future. However, her experiences in the BA program and on the job have helped her make sense of where she wants to be professionally.

Until this day I do not think teaching is for me. However, the BA is asking me now to have a class to be able to pass some classes and I am independent now so I need an income to sustain myself. I sometimes enjoy my profession, but it is something I do not plan to do the rest of my life. (Martha, e-mail interview)

Although, most students enter the BA program in TESOL to become English teachers, she does not see herself teaching in the future. She is mainly teaching now because it is a requirement for the BA, and to provide for herself. Instead she sees herself in higher education.

Honestly, I see myself as a doctor . . . weather in education, psychology, or research. (Martha, semi-structured interview)

Martha’s plans for the future have become clearer. Through her experience in the BA program and teaching, she now knows that her true goal is to continue studying and eventually obtain a PhD. It should also be relevant to mention that this excerpt demonstrates an inconsistency within her professional identity. Although she is currently teaching, her imagined identity is not that of a teacher, but that of a doctor in different fields.

Similar to Martha’s events, Maria also began to teach because it was a requirement in the BA program and out of economic need. Both of these participants’ stories parallel in that aspect.

I started teaching in a public school in a very poor area. I had 40 students in six classes. I did not know how to teach anything nor how to control the students in the first place. However, since going to school required to spend money on the bus ride and on food, my parents did not have money at that time and I had to find a way to study and work at the same time. (Maria, e-mail interview)Maria also details her feelings of insecurity due to her lack of preparation at that time. However, because it was a requisite of the program and she lacked economic support from her parents, she had to teach.

For these participants, entering the BA program has not only given them the opportunity to teach, but also to change their perspective on ELT. Maria, for example, makes it apparent that she now has a broader view of what she can do with her linguistic capital.

The BA has really opened my view of all of the things I can do with my English. And even when I might have any other difficulty I could practically work anywhere just because of the language. (Maria, e-mail interview)

Maria displays an optimistic view of her linguistic capital and feels confident that it can open more doors for her.

Ian conveys entering the BA program as a phase or more specifically, as an “intrinsic critical phase” (Measor as cited in Rolls & Plauborg, 2009). Ian’s critical phase began as early as in his first semester of the BA program. He describes these phases as stages and clearly states how each phase is different. These incidents lead him, as Strauss (as cited in Sikes et al., 2001) puts it, to explore his new conceptions that were created through the BA program in TESOL.

I recall those phases being different stages in which I was in. I remember that first and second semester were stages in which I was introduced to the BA and I was becoming adapted to the new lifestyle in which my weekends . . . were going to be spent at school. There were a few moments in which I felt pressured due to the work load in these semesters (first and second), but I don’t think there could have been a better way for me to adapt to this new lifestyle . . . The second phase, I believe, began in third semester in which loads of theory were given to me. Although I felt more pressured than in first and second semester, I got the opportunity to begin working, and I attempted to relate theory with what I was doing amongst my students. I began to notice the connections . . . I enjoyed the job opportunity I had at the moment, and this made me feel as if I was studying something I really enjoyed and felt as if I could teach for a living. I would interpret this as a critical incident. I had my first job and I was happy with teaching and trying out new things in the classroom. (Ian, e-mail interview)

Ian makes it clear that his different phases in the BA program helped him adapt to the student lifestyle and to find a profession that he could see himself practicing for a living. It is through both experiences in the BA program and in his teaching practice that he makes connections and finds his vocation.

The incidents these students live while in the BA program help them in many ways. They helped them discover who they were and where they stood/stand in the ELT profession. They are able to begin a journey in ELT, or decide that ELT is not for them. The critical incidents that the participants undergo while in the BA program are related to Tripp’s (2012) “historical dimension”: “how knowing something about what has happened to us and what we have done, tells us something about who and where we are, and where we might be going” (p. 97). In any case, it helped them see in what direction to steer.

This set of critical incidents occurred once the participants had entered the BA in TESOL program. They all described the different aspects of the BA program; beginning to teach and going through an adaptation phase in the BA program. Martha and Maria began to teach out of economic need and because it was a requirement for the BA. These two participants also shared that through teaching and the BA program their perspectives on teaching changed or were consolidated. Ian, on the other hand, described his process of adaptation to the BA program, and depicted it as a two-phase process.

On the Job

From the data, we found that the participants had critical incidents early in their lives that affected their teaching in particular ways. For some, their learning experience in the US affected their perspective of the Mexican school system upon returning as we see with Maria and Norma. For participants such as Martha, the influence of her family and previous work experience were critical incidents which can directly be correlated with her teaching practice.

Maria construed her experience of learning the language, and described it as “natural”. She made a comparison between the manner in which she learned the language and how her students are learning it.

I learned English by going to two different classes. At the start of my day in second grade elementary I would start by going to class with my normal teacher . . . then I would go with my ESL teacher after recess . . . I remember playing with Barbie dolls along with the other students who were there but we would play in silence because the dolls could not speak if it was not in English. (Maria, e-mail interview)

As for my students now, I find they have to learn grammar and I wish I did not have to teach that to them but, I have to . . . They don’t have much exposure so they really cannot just learn naturally like I did. However, they are still kids, and deserve to have fun. I could just look up how to teach grammar online and stuff, but would this really teach them English? (Maria, e-mail interview)

Based on Measor’s “extrinsic critical phase” (as cited in Rolls & Plauborg, 2009), which in Maria’s case refers to learning the language, her attitude towards the teaching of grammar is identified. Maria holds a strong opinion toward the teaching of grammar and questions if grammar instruction is truly necessary. The critical incident at hand is her experience in her ESL classes. This incident has given her a strong opinion against the teaching of grammar.

Going to school in the us can also have an impact on how these transnational students see their teachers and themselves as teachers. In Norma’s story, she described her American teachers and her Mexican teachers in a very peculiar way.

Bad (her teacher) . . . in my opinion, she was very strict because the context was different for me. When I was in the us, the teachers were very loving, and even did this on the back (patted). Here they tell you “Shut up!”, and I would say, “Why are they screaming at me, they wouldn’t do that over there.” But, now that I am a teacher, I understand that the context is different. (Norma, semi-structured interview)

This comparison between the two types of teachers later influences her teaching style. In her autobiography, she stated that she tried to be a loving and sweet teacher, but much to her dismay she had to change her teaching style. She drew from her memories of her teachers in the US, and made comparisons with her teachers in Mexico. At first, this comparison was negative as she viewed her Mexican teachers as aggressive. However, once she obtained some knowledge of the context, she was able to understand their behavior and even adopted this in her own teaching.

When the children ignored me when I used to talk so sweet, I guess it sounded insecure for them. It was like they did not respect me, just for being sweet. I guess they were just not used to that. (Norma, e-mail interview)

When she began to teach, she approached her students in a “sweet”, loving way. Nonetheless, her students did not react positively to this behavior, and she felt that they were not respecting her. Her students were not the only ones who reacted to her “sweet” teaching style.

Teachers also told me I needed to show more authority, otherwise they (students) would take you as a joke. (Norma, e-mail interview)

In combination with her students’ reactions, and her co-workers’ advice, she decided that the best option was to consider the context in which she was working and changed her teaching style.

Basically, I got to believe and take my role as the teacher, like it’s no joke I’m the teacher and then I got to speak firmly to them without fears, without unbelieving my role. I don’t get so “playful” or dynamic anymore, because when I decide to be a little more relaxed with them to test if they could handle it, it turns all into a mess. Every once in a while I like to spice up my class, although I am aware I’m taking a risk and they probably go crazy. Again, they are probably not used to that “freedom” per se. They really perform better with the guidance and even control from teachers in my own experience and context. (Norma, e-mail interview)

Norma’s story depicted the complexities of teaching. She came into the profession with an idea that teachers were “sweet”, but she soon realized that due to her context, she needed to become the “strict Mexican teacher”. Through this “intrinsic critical phase” (Measor as cited in Rolls & Plauborg, 2009), she was able to define herself as a teacher, and also describe the students in her context.

There are many factors that influence who we are as teachers. In Norma’s case, the context and her experiences with teachers in the US and Mexico all had a tremendous impact on her teaching style. In Martha’s story, we see how her family and past employment experiences shaped her attitude towards her students.

I think that not only my experience working in high school, but also the way I was raised at home. My parents always asked so much from me. I was expected to do perfect all the time and now I expect my students to do the same. This has been a problem for me because of course my students do not respond as I expect and now I have understood that they do not really have to. A lot of students say I am very strict and I think so too, but the way I am has worked for me and I feel comfortable working like this. I see my students as if their learning was my responsibility and so I think that is why I am so hard on them. (Martha, e-mail interviews)

Martha’s family values of hard work were demonstrated through her working at an early age while still in high school. These values now reflect in her teaching, despite the response from her students. With Martha, we have an example of how her personal identity transfers over to her professional identity.

The critical incidents previously explored affected the participants’ teaching practice in different ways. Maria, for example, had an apparent, negative view toward grammar instruction in the classroom, which was a result of her own language learning experience. Norma explained a similar story. She assimilated a teaching style based on her experience with US teachers. This teaching style later proved to be unfruitful for her context, thus resulting in a change of teaching style. Martha described how her family values influenced her as a teacher, and how it reflected in her teaching.

Conclusions

Through this study, we were able to explore critical incidents in the lives of transnational student/teachers in the BA program in TESOL. The theme of critical incidents arose after the data were analyzed. We discovered that the participants had gone through critical incidents during different critical phases. Three different critical phases in the data were found.

The reasons that led the participants toward making a decision to study for a BA in TESOL varied, but their linguistic capital played a key role in the decision. The first critical phase that was identified was before the students had entered the BA in TESOL program from their experiences in the us learning the English language. In this phase, different critical incidents were found. For one of the participants, it was an outside influence from a teacher who motivated him to choose to pursue a BA in TESOL. His teacher noticed a quality in him other than his linguistic capital that was representative of a good teacher. For other participants, the motivation to enroll in the BA in TESOL program came from an intrinsic factor. For participants such as Maria, motivation came from the urge to help others learn the language. As she stated in her story, she did not want other students to struggle as she did while learning the language. The critical incidents for the four participants were different, but they all resulted in the life-changing decision of enrolling in a BA program in TESOL.

After the students had made their decisions to enroll in the program, they began a new critical phase. This phase occurred during their formation process in the BA program in TESOL. For most of the participants, the nature of the BA program drove them to seek a teaching job. This was one of the first critical incidents that participants, like Martha, went through in the BA program. For others, such as Ian, the notion of the concept of critical incidents was more notable, and he was able to describe his experience in the BA program as a process in which different stages were involved. He started in the acquisition stage, where he was introduced to new concepts, and later was able to apply these concepts and see them at work in his teaching practice. For most, the critical incidents during the BA program phase motivated them to teach.

The final critical phase that was described in this study was their teaching practice. Some participants had a noticeable influence in their teaching practice from their own learning experience. In the cases of Norma and Maria, the influence from their experiences in the US was extremely evident. Maria took from her experiences learning the language, and Norma from her experiences with teachers in the US. From those experiences, their perceptions on how to teach a language, and how a teacher should behave in class were shaped, thus creating their teacher identities. However, just as identities are in constant change and negotiation, their perceptions on teaching practices and teacher behavior also changed as they gained more experience.

Through these three critical phases, we were able to explore and re-story different critical incidents in the lives of transnational student/teachers in this context; the BA program in TESOL. We discovered that the incidents one has in life are directly correlated to the decisions we make. However, this exploration led us to more questions and possible directions that could be taken using the analysis of critical incidents.

Implications and Limitations

This study aids in understanding the motives behind transnationals’ decisions to become English teachers. Through the analysis of critical incidents, we were able to explore the identity formation of transnational EFL student-teachers before the BA program in TESOL, during the BA program, and in their teaching practice. The analysis of these critical phases can lead to a better understanding of the life-changing decisions these individuals made when deciding to become ELTs. This analysis could benefit the BA program in TESOL at Universidad de Guanajuato by providing the program designers with valuable knowledge when adapting or changing curriculum to explore or make use of the experiences transnational students wield. However, this study could have a greater impact with several modifications.

The limitations of this study are strictly technical, and if not present, could have provided a lengthy discussion of critical incidents. One of these principal technical constraints was the number of participants. In the future, we would like to work with more than five participants in order to have a larger sample of critical incidents, thus finding more similarities or differences.

Further Research

As we mentioned before, from the data we were able to identify three critical phases consisting of critical incidents. For future research, we suggest that these three phases be dissected separately, as each is rich in data. For the first phase, the researcher can take many directions. He or she can explore the influence of family or the influence of having learned the language on their decisions to pursue a BA in TESOL. For the second phase, while in the BA program, the researcher may develop a framework of the process or critical phase of going through the BA program in TESOL. This could be used to describe how or if this process influences participants’ teaching practice and professional identity formation.

References

Angelides, P. (2001). The development of an efficient technique for collecting and analyzing qualitative data: The analysis of critical incidents. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 14(3), 429-442. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518390110029058.

Barkhuizen, G. (2011). Narrative knowledging in TESOL. TESOL Quarterly, 45(3), 391-414.

Beijaard, D., Meijer, P. C., & Verloop, N. (2004). Reconsidering research on teachers’ professional identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(2), 107-128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2003.07.001.

Chase, S. E. (2011). Narrative inquiry: Still a field in the making. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 421-434). Thousand Oaks, US: Sage Publishing.

Christians, C. G. (2011). Ethics and politics in qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 61-80). Thousand Oaks, US: Sage Publishing.

Clandinin, D. J., Pushor, D., & Orr, A. M. (2007). Navigating sites for narrative inquiry. Journal of Teacher Education, 58(1), 21-35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487106296218.

Clarke, M., Hyde, A., & Drennan, J. (2013). Professional identity in higher education. In B. M. Kehm, & U. Teichler (Eds.), The academic profession in Europe: New tasks and new challenges (pp. 7-21). Dublin, IE: Springer Science+Business. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4614-5_2.

Denscombe, M. (2007). The good research guide: For small-scale social research projects (3rd ed.). Glasgow, UK: McGraw-Hill Education.

Flanagan, J. C. (1954). The critical incident technique. Psychological Bulletin, 51(4), 327-358. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0061470.

Flick, U. (2006). An introduction to qualitative research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, US: Sage Publishing.

Jerdee, D. L. (2010). Messages of nationalism in Mexican and US textbooks: Implications for the national identity of transnational students (Master’s thesis). Loyola University Chicago, USA. Retrieved from http://ecommons.luc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1503&context=luc_theses.

Kumpusalo, E., Neittaanmäki, L., Mattila, K., Virjo, I., Isokoski, M., Kujala, S., . . . Luhtala, R. (1994). Professional identities of young physicians: A Finnish national survey. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 8(1), 69-77. https://doi.org/10.1525/maq.1994.8.1.02a00050.

Moctezuma, L. (2008). El migrante colectivo transnacional: senda que avanza y reflexión que se estanca [The collective transnational migrant: A path that continues and reflection that falters]. Sociológica, 23(66), 93-119.

Mora Pablo, I. (2014). Unveiling labels through a narrative approach. In C. Moore (Ed.), Collecting and interpreting qualitative data: Principles in practice (pp. 39-61). Mexico, MX: Universidad de Guadalajara, Centro Universitario de la Costa, CUC.

Morrison, K., & Lui, I. (2000). Ideology, linguistic capital and the medium of instruction in Hong Kong. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 21(6), 471-486. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434630008666418.

Norton, B., & Toohey, K. (2011). Identity, language learning, and social change. Language Teaching, 44(4), 412-446. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444811000309.

Ospina, S. M., & Dodge, J. (2005). It’s about time: Catching method up to meaning—the usefulness of narrative inquiry in public administration research. Public Administration Review, 65(2), 143-157. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2005.00440.x.

Rolls, S., & Plauborg, H. (2009). Teachers’ career trajectories: An examination of research. In M. Bayer, U. Brinkkjaer, H. Plauborg, & S. Rolls (Eds.), Teachers’ career trajectories and work lives (pp. 9-28). New York, US: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2358-2_2.

Sikes, P., Measor, L., & Woods, P. (2001). Critical phases and incidents. In J. Soler, A. Craft, & H. Burgess (Eds.), Teacher development: Exploring our own practice (pp. 104-115). Thousand Oaks, US: Sage Publishing.

Tripp, D. (2012). Critical incidents in teaching: Developing professional judgement (Classic edition). New York, US: Routledge.

Trueba, E. T. (2004). The new Americans: Immigrants and transnationals at work. Oxford, UK: Rowman & Littlefield.

Watkins-Goffman, L. (2006). Understanding cultural narratives: Exploring identity and the multicultural experience. Ann Arbor, US: University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.6695.

Wortham, S. (2006). Learning identity: The joint emergence of social identification and academic learning. New York, US: Cambridge University Press.

Zúñiga, V., & Hamann, E. T. (2009). Sojourners in Mexico with US school experience: A new taxonomy for transnational students. Comparative Education Review, 53(3), 329-353. https://doi.org/10.1086/599356.

About the Authors

José Irineo Omar Serna-Gutiérrez is an in-service teacher-student at Universidad de Guanajuato. He currently teaches English at Universidad de Guanajuato in the Department of Languages. He holds a BA in TESOL and is currently studying for an MA in Applied Linguistics in English Teaching at Universidad de Guanajuato.

Irasema Mora-Pablo is a full-time teacher at Universidad de Guanajuato in the Language Department and currently coordinates the MA program in Applied Linguistics in English Language Teaching. She holds a PhD in Applied Linguistics (University of Kent, UK). Her areas of interest are bilingualism, Latinos studies, and identity formation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank PRODEP-SEP for funding this study and also the participants who shared their stories with us.

References

Angelides, P. (2001). The development of an efficient technique for collecting and analyzing qualitative data: The analysis of critical incidents. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 14(3), 429-442. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518390110029058.

Barkhuizen, G. (2011). Narrative knowledging in TESOL. TESOL Quarterly, 45(3), 391-414.

Beijaard, D., Meijer, P. C., & Verloop, N. (2004). Reconsidering research on teachers’ professional identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(2), 107-128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2003.07.001.

Chase, S. E. (2011). Narrative inquiry: Still a field in the making. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 421-434). Thousand Oaks, US: Sage Publishing.

Christians, C. G. (2011). Ethics and politics in qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 61-80). Thousand Oaks, US: Sage Publishing.

Clandinin, D. J., Pushor, D., & Orr, A. M. (2007). Navigating sites for narrative inquiry. Journal of Teacher Education, 58(1), 21-35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487106296218.

Clarke, M., Hyde, A., & Drennan, J. (2013). Professional identity in higher education. In B. M. Kehm, & U. Teichler (Eds.), The academic profession in Europe: New tasks and new challenges (pp. 7-21). Dublin, IE: Springer Science+Business. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4614-5_2.

Denscombe, M. (2007). The good research guide: For small-scale social research projects (3rd ed.). Glasgow, UK: McGraw-Hill Education.

Flanagan, J. C. (1954). The critical incident technique. Psychological Bulletin, 51(4), 327-358. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0061470.

Flick, U. (2006). An introduction to qualitative research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, US: Sage Publishing.

Jerdee, D. L. (2010). Messages of nationalism in Mexican and US textbooks: Implications for the national identity of transnational students (Master’s thesis). Loyola University Chicago, USA. Retrieved from http://ecommons.luc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1503&context=luc_theses.

Kumpusalo, E., Neittaanmäki, L., Mattila, K., Virjo, I., Isokoski, M., Kujala, S., . . . Luhtala, R. (1994). Professional identities of young physicians: A Finnish national survey. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 8(1), 69-77. https://doi.org/10.1525/maq.1994.8.1.02a00050.

Moctezuma, L. (2008). El migrante colectivo transnacional: senda que avanza y reflexión que se estanca [The collective transnational migrant: A path that continues and reflection that falters]. Sociológica, 23(66), 93-119.

Mora Pablo, I. (2014). Unveiling labels through a narrative approach. In C. Moore (Ed.), Collecting and interpreting qualitative data: Principles in practice (pp. 39-61). Mexico, MX: Universidad de Guadalajara, Centro Universitario de la Costa, CUC.

Morrison, K., & Lui, I. (2000). Ideology, linguistic capital and the medium of instruction in Hong Kong. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 21(6), 471-486. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434630008666418.

Norton, B., & Toohey, K. (2011). Identity, language learning, and social change. Language Teaching, 44(4), 412-446. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444811000309.

Ospina, S. M., & Dodge, J. (2005). It’s about time: Catching method up to meaning—the usefulness of narrative inquiry in public administration research. Public Administration Review, 65(2), 143-157. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2005.00440.x.

Rolls, S., & Plauborg, H. (2009). Teachers’ career trajectories: An examination of research. In M. Bayer, U. Brinkkjaer, H. Plauborg, & S. Rolls (Eds.), Teachers’ career trajectories and work lives (pp. 9-28). New York, US: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2358-2_2.

Sikes, P., Measor, L., & Woods, P. (2001). Critical phases and incidents. In J. Soler, A. Craft, & H. Burgess (Eds.), Teacher development: Exploring our own practice (pp. 104-115). Thousand Oaks, US: Sage Publishing.

Tripp, D. (2012). Critical incidents in teaching: Developing professional judgement (Classic edition). New York, US: Routledge.

Trueba, E. T. (2004). The new Americans: Immigrants and transnationals at work. Oxford, UK: Rowman & Littlefield.

Watkins-Goffman, L. (2006). Understanding cultural narratives: Exploring identity and the multicultural experience. Ann Arbor, US: University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.6695.

Wortham, S. (2006). Learning identity: The joint emergence of social identification and academic learning. New York, US: Cambridge University Press.

Zúñiga, V., & Hamann, E. T. (2009). Sojourners in Mexico with US school experience: A new taxonomy for transnational students. Comparative Education Review, 53(3), 329-353. https://doi.org/10.1086/599356.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Isaac Frausto-Hernandez. (2025). At the Intersection of Transnationalism, Identity, and Conocimiento: An Autoethnography. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), p.1539. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111539.

2. Bharat Prasad Neupane, Laxman Gnawali, Hem Raj Kafle. (2022). NARRATIVES AND IDENTITIES: A CRITICAL REVIEW OF EMPIRICAL STUDIES FROM 2004 TO 2022. TEFLIN Journal - A publication on the teaching and learning of English, 33(2), p.330. https://doi.org/10.15639/teflinjournal.v33i2/330-348.

3. Abdul Karim, Muhammad Kamarul Kabilan, Shahin Sultana, Evita Umama Amin, Mohammad Mosiur Rahman. (2024). Reflecting on Reflections Concerning Critical Incidents in Developing Pre-Service Teachers’ Professional Identity: Evidence from a TESOL Education Project. English Teaching & Learning, 48(3), p.291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-023-00140-1.

4. Steve Daniel Przymus, Melissa Mendoza. (2025). Now you see me, now you don't: Unveiling adolescent multilingual identities through magic, storytelling, and translanguaging. Linguistics and Education, 86, p.101383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2025.101383.

5. Müfit Şenel. (2021). Exploring ELT Students’ Professional Identity Formation through the Perspectives of Critical Incidents. European Journal of Educational Research, volume-10-2021(volume-10-issue-2-april-2021), p.629. https://doi.org/10.12973/eu-jer.10.2.629.

6. Steve Daniel Przymus, M. Martha Lengeling, Irasema Mora-Pablo, Omar Serna-Gutiérrez. (2022). From DACA to Dark Souls: MMORPGs as Sanctuary, Sites of Language/Identity Development, and Third-Space Translanguaging Pedagogy for Los Otros Dreamers. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 21(4), p.248. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2020.1791711.

7. Mehmet Kılıç, Emrah Cinkara. (2020). Critical incidents in pre-service EFL teachers’ identity construction process. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 40(2), p.182. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2019.1705759.

8. Jhon Holguin-Alvarez, Susana Oyague-Pinedo, Silvia Samame-Gamarra, Gloria María Villa-Córdova, Dasha Pariona-Tacsa. (2020). Incidentes críticos formativos: evidencias de la soledad pedagógica docente en contextos vulnerables. Praxis, 16(2), p.151. https://doi.org/10.21676/23897856.3463.

9. Krisztina Zimányi. (2025). Multilingual Education Yearbook 2025. Multilingual Education Yearbook. , p.43. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-83045-7_3.

10. Martha García Chamorro, Monica Rolong Gamboa, Nayibe Rosado Mendinueta. (2022). Initial Language Teacher Education: Components Identified in Research. Journal of Language and Education, 8(1), p.231. https://doi.org/10.17323/jle.2022.12466.

11. Alejandra Núñez Asomoza. (2019). TRANSNATIONAL YOUTH AND THE ROLE OF SOCIAL AND SOCIOCULTURAL REMITTANCES IN IDENTITY CONSTRUCTION. Trabalhos em Linguística Aplicada, 58(1), p.118. https://doi.org/10.1590/010318138654041455172.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

Copyright (c) 2018 Author

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.