“Claim – Support – Question” Routine to Foster Coherence Within Interactive Oral Communication Among EFL Students

Rutina “afirmar – respaldar – preguntar” para fomentar la coherencia en la interacción comunicativa oral en estudiantes de inglés como lengua extranjera

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v20n2.63554Keywords:

Claim - support - question routine, coherence, discourse competence, interactive communication (en)coherencia, competencia discursiva, comunicación interactiva, rutina afirmar - respaldar - preguntar (es)

This article reports on the results of an action research study that aimed to determine the effect of a thinking routine in the development of coherence in speaking interactions. The study was carried out with two groups of second year business students in an English as a foreign language programt a university in southern Chile. A mixed methods approach was used to collect data before and after the intervention through questionnaires and pre- and post-tests. The findings suggest that the impact of the application of the routine was significant in promoting the speaking competence, especially in developing coherence within interactive communication.

“Claim – Support – Question” Routine to Foster Coherence Within Interactive Oral Communication Among EFL Students

Rutina “afirmar – respaldar – preguntar” para fomentar la coherencia en la interacción comunicativa oral en estudiantes de inglés como lengua extranjera

Fabiola Arévalo Balboa*

Universidad Austral de Chile, Valdivia, Chile

Mark Briesmaster**

Universidad Católica de Temuco, Temuco, Chile

*fabiola.arevalo@uach.cl

**briesmaster@uct.cl

This article was received on March 26, 2017 and accepted on March 13, 2018.

How to cite this article (APA, 6th ed.):

Arévalo Balboa, F., & Briesmaster, M. (2018). “Claim – support – question” routine to foster coherence within interactive oral communication among EFL students. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 20(2), 143-160. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v20n2.63554.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This article reports on the results of an action research study that aimed to determine the effect of a thinking routine in the development of coherence in speaking interactions. The study was carried out with two groups of second year business students in an English as a foreign language programt a university in southern Chile. A mixed methods approach was used to collect data before and after the intervention through questionnaires and pre- and post-tests. The findings suggest that the impact of the application of the routine was significant in promoting the speaking competence, especially in developing coherence within interactive communication.

Key words: Claim - support - question routine, coherence, discourse competence, interactive communication.

Este artículo reporta los resultados de un estudio de investigación-acción que apuntaba a determinar el efecto de una rutina de pensamiento creativo en el desarrollo de la coherencia en las interacciones orales. El estudio fue conducido con dos grupos de estudiantes de segundo año de Ingeniería Comercial de una universidad del sur de Chile. Se usó un método mixto para analizar los datos obtenidos antes y después de la intervención a través de cuestionarios y pruebas. Los resultados sugieren que el impacto de la aplicación de la rutina podría ser considerado significativo para promover la expresión oral, especialmente en el desarrollo de coherencia dentro de la interacción comunicativa.

Palabras clave: coherencia, competencia discursiva, comunicación interactiva, rutina afirmar - respaldar - preguntar.

Introduction

Since the 1980s the paradigm has shifted in language teaching from a grammar-based approach to a more communicative one, thus students now are expected to use the language and communicate through it. However, there are two factors that affect the achievement of this goal in Chile: One is that many students do not feel ready to produce the target language, which makes developing oral skills in students a challenge of major proportions. The other is that students are taught in an English as a foreign language (EFL) context, which means they have few opportunities to access the target language outside the classroom (Brown, 2001). This lack of exposure often causes students to become disengaged in classroom activities, especially those which require them to speak.

In an attempt to reduce the impact of the aforementioned factors underlying students’ reluctance to speak in the classroom, the present research aims to investigate how the explicit teaching of the thinking routine Claim, Support, Question (CSQ), developed by Richhart (2002) and implemented by Casamassima and Insua (2015), could foster student coherence within interactive speaking.

Therefore, this study hopesto shed some light on speaking, coherence, and interactive communication, how they relate to each other, and on the impact these correlations may ultimately have on students.

Literature Review

As language represents the most basic form of human communication (Lazaraton, 2001), it is not surprising to find that there are many English courses whose main objective is for students to achieve communicative competence. In fact, the role of foreign language teaching is “to extend the range of communication situations in which the learner can perform with focus on meaning” (Littlewood, 1981, p. 89). Thereby the teaching of English is associated with the learners’ ability to communicate in the target language. When students fail to fulfill the given tasks, they are judged to be lazy or reluctant to speak (Tsiplakides & Keramida, 2009); nevertheless, students’ low participation might not be due to a lack of motivation but to other factors, as the inability to take part in communicative tasks (Gaudart, 1992). Littlewood (2004),for example, attributes the problem tofactors such as tiredness, fear of being wrong, lack of interest in the class, lack of knowledge in the subject, shyness, and insufficient time to formulate ideas. Based on these data, teachers must be able to identify which of the aforementioned factors justify students’ reluctance to engage in speaking activities before labeling them as lazy or careless students.

Interactive Speaking

Within the speaking skill, interactive speaking belongs to one of the four types of speaking, proposed by Brown and Abeywickrama (2010), which require at least two interlocutors to discuss a given topic by taking turns to express their ideas. According to them, there are two purposes for maintaining interactive speaking: (a) transactional (when the speakers use language for specific information exchange), and (b) interpersonal (when the speakers use language to maintain social interaction).

Communicative language teaching (CLT) has as its primary objective interactive speaking; a goal where the nature of communication is collaborative and shaped by the interaction of its participants (Savignon, 2001). Canale and Swain (1980) claim that “the primary objective of a communication oriented second language programme must be to provide the learners with the information, practice, and much of the experience required to meet their communicative needs in the second language” (p. 28). Consequently, if teachers want their students to interact with their peers using the target language, first they will need to equip them with the necessary tools and allow them to experiment with the language; otherwise it would be inconsistent to provide the students with speaking practice at the intensive level—for example—and then to evaluate them in interactive speaking.

Giving students the opportunity to interact is highly beneficial because it brings the communicative task closer to the type of situation that students may encounter in the real world (Littlewood, 1981), which is likely to keep the students on task for longer periods. Along with this, interaction, which drives negotiation, also facilitates learning as learners’ attention is drawn to the linguistic forms that need to be improved (Gass, 1997).

Discourse Competence

The fact that communicative competence is a complex construct that goes beyond the mastering of grammatical rules and allows the appropriate use of language in different communicative situationscannot be ignored (Hymes, 1972). It is more than merely giving students a topic to discuss (Shumin, 2002) and to achieve this competence “a number of processes and factors work together, whose importance may vary dependent on the particular communicative situation involved” (Rickheit, Strohner, & Vorwerg, 2008, p. 46). Canale and Swain (1980) and Canale (1983) propose that being able to communicate requires the management of four sub-competences, these are: grammatical competence (knowing the rules of language functioning), sociolinguistic competence (awareness of meaning in varied social contexts), strategic competence (how to overcome communicative breakdowns by using compensatory strategies), and discourse competence (how language is organized and put together to convey meaning).

Discourse competence deals with how words, phrases, and sentences are put together to convey meaningful language stretches (Shumin, 2002). At this point it is important to mention that although in discourse analysis research the term discourse is used to refer to either spoken or written stretches of language, for the purposes of this study the concepts of discourse and discourse competence will be used to refer to spoken language. Bygate (2001) defines the complexity of spoken discourse and states that the teaching of the speaking skill rarely focuses on the production of spoken discourse.

Coherence

Within the discourse competence and along with cohesion—how words and phrases make sense at sentence level (Min, n.d.)—the concept of coherence plays an important role after decades of being dismissed by linguists, and emerges as “a key concept, perhaps even the key concept, in discourse . . . analysis” (Bublitz, 1999, p. 1). However, some authors (Bublitz, 1989, Dontcheva-Navratilova & Povolná, 2009, Renkema, 2004, Tanskanen, 2006, Wang & Guo, 2014) agree that coherence is a difficult concept to define and there is no general agreement yet on a clear definition, although it seems to be connected to how the listener relates the discourse to his or her knowledge. Thus, what may be coherent for some may not be for others. But “there is an attempt to reach a more user—and context—oriented interpretive understanding which is more interactively negotiated and is less dependent on the language . . . itself” (Bublitz, 1999, pp. 1-2), especially considering that coherence relationships are sufficient for successful discourse comprehension (Blakemore, 2001).

This study will adhere to the conception of coherence as that which makes discourse “hang together” in a meaningful way regarding a particular topic. Since coherence is pursued to achieve communicative competence as the ultimate goal, it is not surprising that Geluykens (1999) argues that it takes two to be coherent, as in this interaction “[at least] two participants attempt to come to some agreement on topical coherence by negotiating about it” (p. 35).

Developing coherence in speaking is a complex and demanding task. Therefore, the routine which will be explained next is an attempt to contribute to students’ development of speaking coherence in interactive speaking.

Claim, Support, Question Routine

CSQ is a thinking routine proposed by Ritchhart (2002) and was developed along with other thinking routines as part of the Visible Thinking project within the Project Zero at Harvard University. Ritchhart, Palmer, Church, and Tishman (2006) explain that CSQ is a subcategory that belongs to the learning routines, as “it provides a recognizable structure for students to work within” (p. 6); as well as to the discourse routines, because it “structures the discussion and sharing of students’ learning” (p. 6), not in terms of grammar, but by providing a clear organization that makes the idea hang together.

This routine was originally part of a project dedicated to promoting critical thinking among students in art classes and the like, and it attempts to make the students’ thoughts visible by means of verbalizing them (Ritchhart & Perkins, 2008). Thus, because of its characteristics and as suggested in Casamassima and Insua’s study (2015), the routine attempts to serve the purpose of helping EFL students to organize their thoughts in a given situation. They can have discussions, for example, where they “interact with each other to make a decision or solve a problem” (Casamassima & Insua, 2015, p. 24). The routine consists of three steps:

- Claim: Students make a statement about a given topic.

- Support: Students provide information to defend their claim. This can be statistical information or even an example to give evidence.

- Question: Students formulate a question related to their claim to pass the speaking turn to their classmate.

By using CSQ, it is possible for learners to negotiate meaning and build coherence while developing topical organization (Geluykens, 1999). Due to the aforementioned characteristics, the routine allows students to follow each step, while using their current level of linguistic competence; which is only the means to express their thoughts about a particular topic. The routine encourages students to provide a complex answer that goes beyond the “just because” phrase. Furthermore, as this routine encourages students to reason with evidence, it also enables the teacher to have an idea of how students form an opinion related to certain topics. In other words, the routine attempts to show how the thinking process becomes visible. This study argues that the CSQ routine could help students develop coherence as they can follow a recognizable structure to express their thoughts within an interactive speaking situation.

Method

The current study falls under the category of action research, which is done by teachers who seek to evaluate and improve an aspect of their teaching by generating a solution for a practical problem (Parsons & Brown, 2002). In order to answer the research question that drove this action research: “How does the CSQ routine influence the development of coherence within speaking interaction in EFL learners?” a mixed methods approach was used mainly for two reasons: (a) its dual nature that enables the statistical analysis of the quantitative data and the interpretation of qualitative data, and (b) the triangulation of the data collected that allows a richer insight into the issues of the study (Wiśniewska, 2011).

As an attempt to improve the coherence of students in oral performance, this action research sought to determine the effects of the CSQ routine in the development of coherence in speaking interactions among EFL students. The implementation of the study consisted of three stages: first a stage to gather information about the students’ initial level of English and perceptions on speaking coherence in both the control group (CG) and the experimental group (EG). In the second stage a routine to enhance coherence in speaking was presented only to the EG, and in the third stage, more information was gathered to measure the impact of the routine on the students (EG only) and any possible changes in their perceptions towards speaking (in both CG and EG).

Context and Participants

The study was carried out with second year undergraduate business students—aged 19 to 21—and who were taking the English III course. Their curricular plan includes five English classes over the course of the program, whose main objective is to prepare them to communicate in the target language. Consequently, the courses are based mainly on the communicative approach mixed, to a lesser degree, with a grammar approach.

Initially the study included two groups of 20 students each that were assigned to each group randomly by the university platform; but, the number of participants decreased due to the fact that some students were exempted from the course, and others dropped it. In the end the study was carried out with the participation of 34 students, 16 in the CG and 18 in the EG. The variation on the number of participants in the display of results can be explained by the absence of some students on the days that the tests or questionnaires were applied. In the CG, all the students answered the questionnaires, but only 14 of them took the tests; while in the EG, 16 students answered the questionnaires and all of them took the tests. All the participants took a placement test that indicated they were between A2 and B1 level of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) (Council of Europe, 2001). Based on the results obtained in the pretest, the highest achievement group was chosen as the CG. Therefore, the lower achievement group was chosen to be the EG, as it was thought that they would benefit more and eventually bridge their gap in levels after the intervention. The 34 students willingly accepted to take part in the investigation by signing a consent letter that thoroughly explained the characteristics of the study and what was expected from them. It was requested by the Business School administration that all the participants had to receive the same instruction in order to authorize the investigation, and the consent form had to be sent to the school director for approval. Afterwards, all the students signed the same consent form, which thoroughly explained the characteristics of the study and what was expected from them; it also mentioned the teaching of the CSQ routine. At this point, it is crucial to clarify that the CG did not receive instruction on the routine until all the data presented in this article were collected.

Instruments

Questionnaires

A pre-questionnaire (see Appendix A), partially based on Horwitz, Horwitz, and Cope’s (1986) Anxiety questionnaire, was applied at the beginning of the study to both groups. Even if this study does not focus on anxiety, a modified version of this questionnaire was thought to be useful as it can provide an initial background of students’ speaking perceptions, their own speaking performance appraisal, the factors they relate to their performance, and their use of organizational strategies for speech production. The 16 questions were classified into three variables: perception (students’ perception of their own speaking performance), coherence (students’ perception of their organization of ideas in speech), and motivation (students’ willingness to learn techniques to improve the aspects mentioned in the previous variables). A very similar questionnaire was applied at the end of the intervention, but this time an open-ended question was added to the EG to measure the understanding and use of the technique after the intervention. Students had the opportunity to answer either in English or Spanish, so as not to restrict their opinion because of language limitations (see Appendixes A, B, and C).

Pre- and Post-Test

The speaking part of the preliminary English test (PET) was administered to the students before and after the implementation of the routine. The fact that most of the participants were under the level that this test focuses on (B1) was not an impediment to choose it because the linguistic competence, which students are still developing, is only one of the four criteria that the test assesses. Moreover, linguistic competence “is not sufficient on its own to account for how language is used as a means of communication” (Littlewood, 1981, p. 1). The test assessed the students’ performance under four criteria (grammar and vocabulary, discourse management, pronunciation, and interactive communication) that demand students work independently and collaboratively in order to solve the given tasks. This test was selected because it was more challenging for the students as it takes them a step beyond their current level of proficiency (Krashen, 1982); but mainly because it measures discourse management and interactive communication. Although the other aforementioned criteria were also analyzed, the focus of the study was on those two parameters.

Pedagogical Intervention

In the first stage of the implementation, the pre-test and the questionnaire were applied to all the participants in order to obtain information concerning the students’ initial English level and management of coherence techniques during speaking. Those instruments detected deficiencies in the areas mentioned.

In the second stage, the CSQ routine was explicitly taught only to the students in the EG. Prior to the instruction, two students were given a situation from the current unit of their course book; they were shown pictures of four people and asked to choose one of them to advertise a new chocolate bar. This is the transcription of the dialogue:

Student A: I think Jake is a good option because I think he has a personality and as the chocolate, he has dark hair.

Student B: Emm I think Zoe is a good candidate because is a girl emm and she has a emm how do you say sonrisa? emm smile and emm and I don’t know her CV.

Student A: Emm I think both are good candidates. And I think that the candidate Lily is emm like emm too old, or for another anounce anouncement emm but I think she is not for the emm advertise of a chocolate bar. Emm what do you think about Jake?

Student B: Well, I thought Pete (he laughs)

Student A: I think he is kind, but the people don’t think the personality or how very good he is how he is in his...emm the people only want to see a good appearance and that’s why emm I think Jake and Zoe are the best options.

Student B: Yes.

Then their classmates provided feedback on the performance and mentioned that it was a good conversation but realized that they did not make a decision. After that, the CSQ routine was explicitly taught to the students and they were told that it could be used every time they were asked to discuss or make a decision, in pairs or groups, about any topic. They had to follow three steps: make a point (claim); defend that point by providing reasons, examples, or extra information (support); and pass the speaking turn to a classmate by formulating a question about the topic (question). Then, the other student would follow the same steps and so forth, until they reached a conclusion or agreement. After the explanation of the routine the students were given the same situation again, this time two different students solved the situation by following the steps of the new routine. The students were advised to clap, as an alternative to using a ball as in Casamassima and Insua’s intervention (2015), after each step of the routine in order to make them more aware of the process and also to help them to mechanize the routine. The following is the transcription of the dialogue:

Student A: I think it should be Jake (clap) because he has a good personality and I think people will like him (clap). I don’t know if you agree with me.

Student B: Emm I disagree with you. Emm we should pick Lili (clap) because she is older than the other people and, but she looks healthy. So, the people will think that the chocolate is healthy (clap). What do you think about that?

Student A: I don’t agree with you (clap) because she emm, I don’t think people would like her because she is not emm, like a charismatic person (clap). What do you think?

Student B: Emm, it’s OK. Emm OK, so in that case I guess we should take Pete (clap) because he looks very happy and I don’t know, he emm he has the flow (he laughs). Are you agree with that?

Student A: Yeah, I think you’re right because he looks really funny and we can work with that.

Including the session just described, the CSQ routine was used in eight sessions, where students had the opportunity to acquaint themselves with it while engaging in interactive speaking tasks related to the contents of the course. It also included a written task (see Appendix D) where the students had to elaborate on a given topic with the purpose of helping the visual students to make better sense of the routine (Oxford, 2001). It is important to mention that in order to insert 45 minutes of speaking tasks, it was necessary to entrust the students with the amount of independent work established in the syllabus of the course. In that sense, a type of flipped classroom was conducted where students had to autonomously study the material uploaded to the platform (mainly grammar points and vocabulary) in order to take part in the activities prepared for the class period. In the last stage of the implementation, data were collected again through the post questionnaire and test.

Results

This study reports on the students’ perceptions and performance on speaking. The data collected from the questionnaires and tests were entered into the SPSS 20.0 software, and the data collected from the open question were codified numerically. The results obtained by the control and experimental group, in both pre- and post-tests and questionnaires, were compared and the level of improvement was measured. Then, these results were triangulated with the open-ended answers to determine if there was any significant variation in perception towards the speaking ability before and after the study that could be attributed to the use of the routine taught to the EG during the intervention.

Questionnaires

Regarding students’ perceptions towards speaking, Table 1 shows that both groups initially had 3.09 in perception, but in terms of coherence and motivation the EG was superior by 2.94 over 2.50 and 4.13 over 3.81 respectively. As shown in Figure 1, in the final post questionnaire both groups improved their perception (CG = 0.21 [4%], EG = 0.54 [11%]) and coherence (CG = 0.6 [12%], EG = 0.28 [6%]); while the motivation of the CG decreased by 0.14 (3%), it increased by 0.18 (4%) in the CG. Despite the motivation drop in the CG, both groups witnessed an increase in the total perception (CG = 0.22 [4%], EG = 0.33 [7%]). If the fourth variable (Technique) added to the post questionnaire of the EG is considered—which reveals that 88% of the students understood the routine and found it useful—the total perception increases by 0.5 (9%).

Table 1. Mean Perceptions in Speaking Questionnaire

Figure 1. Perceptions Towards Speaking Post-Intervention

Tests

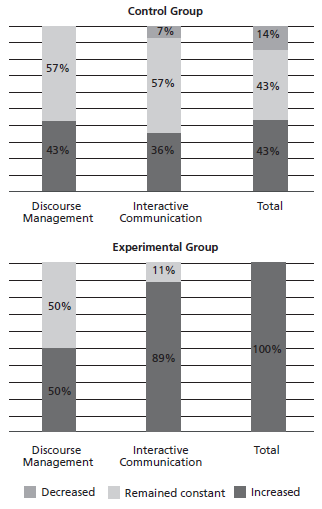

Table 2 shows the mean scores obtained by both groups in the PET pre- and post-tests, whereas Figure 2 illustrates the percentage of improvement. Both groups improved in grammar and vocabulary (CG = 0.15 [3%], EG = 0.5 [10%]), discourse management (CG = 0.42 [9%], EG = 0.73 [14%]), and interactive communication (CG = 0.36 [7%], EG = 1.33 [27%]); meanwhile the pronunciation of the CG decreased by 0.14 (3%), and increased by 0.11 (2%) in the EG. In the end, the post test revealed that both groups had an improvement in the overall speaking performance (CG = 0.2 [4%], EG = 0.66 [13%]).

Table 2. Mean Performance Scores in PET Oral Exam

Figure 2. Students’ Progress on Test Scores

In addition, Figure 3 provides detailed information on the level of achievement obtained by the students in the post-test regarding the two criteria that are crucial to this study: discourse management (DM) and interactive communication (IC), it also includes the total score. Data revealed that out of 14 students in the CG, six (43%) of them increased their scores in DM, and six (43%) maintained them. Whereas in IC five students (36%) increased their scores, 8 (57%) maintained them, and only one (7%) scored lower. Finally, in the total score, six students (43%) increased their total scores, 6 (43%) maintained them, and only two lowered their scores. On the other hand, out of 18 students in the EG, nine students (50%) increased their scores in DM, and the other half maintained them. Regarding IC, 16 students (89%) increased their scores, and two (11%) maintained them. Finally, 100% of the students increased their total scores in the post-test.

Figure 3. Students’ Achievement in Post-Test

Open-Ended Response

Finally, the answers provided by the students to the open-ended question included at the end of the post questionnaire of the EG only revealed that the 16 students (100%) that answered the questionnaire found the routine useful (see Appendix E). As shown in Figure 4, apart from finding the routine useful to organize their ideas while speaking, the students also reported other issues. Two of them (12.5%) remarked that the routine also helped them to interact with their peers; four of them (31.25%) expressed that they would like to keep practising the routine to get better at it, four of them (25%) claimed they needed more vocabulary to complement the use of the routine, and one (6.25%) said that despite the usefulness of the routine s/he still did not feel prepared to speak in the target language or initiate a conversation.

Figure 4. Students’ Opinion on the CSQ Routine

Discussion

The findings seem to prove that the CSQ routine played an important role in the overall performance of the students in the EG, particularly in the development of coherence and interactive communication, which appears to be unavoidable when it comes to spoken discourse (Bublitz, 1999). The fact that the students learned to base their opinion on what their interlocutors had previously said helped their conversations to run smoothly which, consequently, contributed to the improvement of coherence. Recalling the first dialogue presented in the pedagogical intervention, we had that when Student A asked B what he thought about Jake, Student B answered “I thought Pete”. If the previous example is compared with the dialogue that took place immediately after the routine had been presented, it can be seen that the latter interaction made more sense than the former, as the ideas were connected, and the students were trying to come to an agreement.

Student A: Personally, I think the best form for make new friends in the other city is go to different parties because it is a place and it is a situation very sociable and in this moment emm you can dance with different people and you can talk about different situations of the life. Do you agree with me?

Student B: Yes, I agree with you because I think the parties is a emm, is the best way because in the library is less probably than he finds friends there. Emm and I think that he could also play soccer because he can make a lot of friends there. I think that those two options are good. Do you agree with me?

Student A: I agree with you because this partner is a man and he can play football with other boys. But this situation can be emm they fight. But it is very interesting because is a sport that the people can be together. I don’t know if you agree with me.

Student B: Yes, I think that those two options are the right ones for this guy.

Regarding the linguistic competence, the researchers expected the students to claim that they needed to improve their grammar in order to have a better command of the routine, but surprisingly none of the students mentioned it. This finding can be supported by the information presented in the literature review, which argues that insufficient mastering of structure can be compensated by effective spoken discourse. This idea is reinforced by Littlewood (1981) who contends that “this may entail sacrificing grammatical accuracy in favor of immediate communicative ‘effectiveness’” (p. 4).

Aditionally, the students in the EG mentioned factors such as lack of time to practice and lack of vocabulary to convey their message as the main reasons that prevented them from fully using the routine. The fact that the students in the EG needed the teaching and application of a different approach to be able to even out their performance of the CG’s may be an indication of learning issues that can apparently be solved by using different learning strategies or techniques that can vary depending on the chracteristics of the learners’ needs (Oxford, 2001).

It is important to point out that even though the CG made less progress than the EG in the total score, it still obtained the highest score just as it did in the pre-test. This finding demands further reflection, as it may account for the effectiveness of the traditional methodology used in the English courses and/or the high average level of achievement of the participants—which might lead to the assumption that regardless of the method used, they would naturally progress. The latter leads to the urgent need for the researchers to try alternative teaching methods that would eventually boost the potential of high-achieving students, while helping low-achieving students to level up.

To try and understand the decrease in motivation of the CG revealed in the post-questionnaire, it is important to remember that when the students signed the consent letter, they had to be told that a routine would be taught and presumably as they did not perceive any change in methodology during the eight sessions, their motivation decreased. Although motivation is not the main focus of this study, it must be borne in mind that it is the engine that facilitates foreign language instruction and also the fuel that enables students to undergo the process. If it is not present, even the highest achieving students can be negatively impacted (Guilloteaux & Dörnyei, 2008).

Conclusion

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, this study aimed to determine the effects of the CSQ routine in the development of coherence in interactive communication. It can be concluded that the speaking competence has great value in EFL instruction. Also, it was stated that discourse competence is a complex construct, and that coherence is part of it; this is naturally interwoven with interactive communication as a speaker’s message can only convey its meaning when the speaker’s interlocutor understands and validates that message (Bublitz, 1999; Edmondson, 1981; Geluykens, 1999).

The technique applied to the EG appeared to be useful as it promoted the development of both coherence and interaction. Thus, it can be concluded that the application of the CSQ routine benefited the overall speaking performance of the students in the EG, as they improved the results obtained both in the questionnaire and test applied before the intervention; and above all, it benefited them by bridging the gap with the students in the CG. Notwithstanding, the CG also presented an improvement in relation to their initial results on the questionnaire and test, which may indicate that the methodology regularly used to teach English at the university is effective. The study potentially opens a new path for future research that could help to determine the relevance of other areas that also play a role in spoken discourse, such as vocabulary, cohesive devices, exposure, and readiness to communicate in the target language.

References

Blakemore, D. (2001). Discourse and relevance theory. In D. Schiffrin, D. Tannen, & H. E. Hamilton (Eds.), The handbook of discourse analysis (pp. 100-118). Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Brown, H. D. (2001). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy (2nd ed.). New York, US: Longman.

Brown, H. D., & Abeywickrama, P. (2010). Language assessment, principles and classroom practices (2nd ed.). White Plains, US: Pearson Education.

Bublitz, W. (1989). Topical coherence in spoken discourse. Studia Anglica Posnaniensia, 22, 31-51. Retrieved from http://ifa.amu.edu.pl/sap/files/22/02Bublitz.pdf.

Bublitz, W. (1999). Introduction: Views of coherence. In W. Bublitz, U. Lenk, & E. Ventola (Eds.), Coherence in spoken and written discourse: How to create it and how to describe it (pp. 1-10). Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.63.03bub.

Bygate, M. (2001). Speaking. In R. Carter & D. Nunan (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to teaching English to speakers of other languages (pp. 14-20). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667206.003.

Canale, M. (1983). From communicative competence to communicative language pedagogy. In J. C. Richards & R. W. Schmidt (Eds.), Language and communication (pp. 2-27). London, UK: Longman.

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, 1(1), 1-47.

Casamassima, M., & Insua, F. (2015). On how thinking shapes speaking: Techniques to enhance students’ oral discourse. English Teaching Forum, 53(2), 21-29.

Council of Europe. (2001). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Dontcheva-Navratilova, O., & Povolná, R. (2009). Coherence and cohesion in spoken and written discourse. Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars.

Edmondson, W. (1981). Spoken discourse: A model for analysis. London, UK: Longman.

Gass, S. M. (1997). Input, interaction, and the second language learner. Mahwah, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Gaudart, H. (1992). Persuading students to speak in English. Paper presented atthe first Malaysian English Language Teaching Association International Conference.

Geluykens, R. (1999). It takes two to cohere: The collaborative dimension of topical coherence in conversation. In W. Bublitz, U. Lenk, & E. Ventola (Eds.), Coherence in spoken and written discourse: How to create it and how to describe it (pp. 35-54). Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.63.06gel.

Guilloteaux, M. J., & Dörnyei, Z. (2008). Motivating language learners: A classroom-oriented investigation of the effects of motivational strategies on student motivation. TESOL Quarterly, 42(1), 55-77. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1545-7249.2008.tb00207.x.

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. A. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 70(2), 125-132. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1986.tb05256.x.

Hymes, D. H. (1972). On communicative competence. In J. B. Pride & J. Holmes (Eds.), Sociolinguistics: Selected readings (pp. 269-293). Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.

Krashen, S. D. (1982). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Oxford, UK: Pergamon Press.

Lazaraton, A. (2001). Teaching oral skills. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (3rd ed., pp. 103-115). Boston, US: Heinle & Heinle.

Littlewood, W. (1981). Communicative language teaching. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Littlewood, W. (2004). Students’ perspectives on interactive learning. In O. Kwo, T. Moore, & J. Jones (Eds.), Developing learning environments: Creativity, motivation, and collaboration in higher education (pp. 229-244). Hong Kong, HK: Hong Kong University Press.

Min, Y.-K. (n.d.). From the ESL student handbook by Young Min, PhD. Retrieved from http://www.uwb.edu/wacc/resources/esl-student-handbook/coherence.

Oxford, R. (2001). Language learning styles and strategies. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (3rd ed., pp. 357-366). Boston, US: Heinle & Heinle.

Parsons, R. D., & Brown, K. S. (2002). Teacher as reflective practitioner and action researcher. Belmont, US: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

Renkema, J. (2004). Introduction to discourse studies. Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/z.124.

Ritchhart, R. (2002). Intellectual character: What it is, why it matters, and how to get it. San Francisco, US: Jossey-Bass.

Ritchhart, R., Palmer, P., Church, M., & Tishman, S., (2006, April). Thinking routines: Establishing patterns of thinking in the classroom. Paper presented at the AERA Conference. Retrieved from http://www.ronritchhart.com/ronritchhart.com/Papers_files/AERA06ThinkingRoutinesV3.pdf.

Ritchhart, R., & Perkins, D. N. (2008). Making thinking visible. Educational Leadership, 65(5), 57-61. Retrieved from http://www.ronritchhart.com/ronritchhart.com/Papers_files/MTV_ritchhart_perkins.pdf.

Rickheit, G., Strohner, H., & Vorwerg, C., (2008). The concept of communicative competence. In G. Rickheit & H. Strohner (Eds.), Handbook of communication competence (Vol. 1, pp. 15-62). New York, US: Mouton de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110199000.

Savignon, S. J. (2001). Communicative language teaching for the twenty-first century. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (3rd ed., pp. 13-28). Boston, US: Heinle & Heinle.

Shumin, K. (2002). Factors to consider: Developing adult EFL students’ speaking abilities. In J. C. Richards & W. A. Renandya (Eds.), Methodology in language teaching: An anthology of current practice (pp. 204-211). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667190.028.

Tanskanen, S.-K. (2006). Collaborating towards coherence: Lexical cohesion in English discourse. Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.146.

Tsiplakides, I., & Keramida, A. (2009). Helping students overcome foreign language speaking anxiety in the English classroom: Theoretical issues and practical recommendations. International Education Studies, 2(4), 39-44. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v2n4p39.

Wang, Y., & Guo, M. (2014). A short analysis of discourse coherence. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 5(2), 460-465. http://doi.org/10.4304/jltr.5.2.460-465.

Wiśniewska, D. (2011). Mixed methods and action research: Similar or different? Glottodidactica, 37, 59-72. Retrieved from https://repozytorium.amu.edu.pl/bitstream/10593/1693/1/Wisniewska.pdf.

About the Authors

Fabiola Arévalo Balboa holds a BA in English teaching (Universidad Austral de Chile) and an MA in Teaching English as a Foreign Language (Universidad Católica de Temuco, Chile). Currently she works as an EFL teacher at Centro de Idiomas, Universidad Austral de Chile. Her research interests are communicative language teaching and research in education.

Mark Briesmaster has been a language teacher for the past 32 years and holds a doctorate in intercultural education (BIOLA University, USA). He is currently the director of the MA TEFL program at the Universidad Católica de Temuco (Chile). His research interests include learner anxiety, learning styles, teacher roles and autonomy.

Appendix A: Questionnaire: Perceptions in Speaking – CG / EG

Gender:

Age:

Date:

Please select the number that represents how you feel about speaking in the English class: 1 = Strongly agree, 2 = Agree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Disagree, 5 = Strongly disagree.

Appendix B: Questionnaire: Perceptions in Speaking – CG

Gender:

Age:

Date:

Please select the number that represents how you feel about speaking in the English class at this point of the semester: 1 = Strongly agree, 2 = Agree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Disagree, 5 = Strongly disagree.

Appendix C: Questionnaire: Perceptions in Speaking – EG

Gender:

Age:

Date:

Section 1: Please select the number that best represents how you feel regarding the “Think – Support – Question” routine in relation to speaking in the English class: 1 = Strongly agree, 2 = Agree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Disagree, 5 = Strongly disagree.

Section 2: Please write your opinion about the “Claim - Support – Question” routine. Was it useful? How? If it was not useful, please explain why.

Appendix D: Writing Task

Name:

Date:

Instruction: Develop the topic below in 150 - 200 words. Make sure to include two verb tenses, infinitive of purpose, comparatives, adjectives, and frequency expressions.

Teacher’s comments:

Appendix E: Responses to Section 2 in the EG Post-Questionnaire

References

Blakemore, D. (2001). Discourse and relevance theory. In D. Schiffrin, D. Tannen, & H. E. Hamilton (Eds.), The handbook of discourse analysis (pp. 100-118). Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Brown, H. D. (2001). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy (2nd ed.). New York, US: Longman.

Brown, H. D., & Abeywickrama, P. (2010). Language assessment, principles and classroom practices (2nd ed.). White Plains, US: Pearson Education.

Bublitz, W. (1989). Topical coherence in spoken discourse. Studia Anglica Posnaniensia, 22, 31-51. Retrieved from http://ifa.amu.edu.pl/sap/files/22/02Bublitz.pdf.

Bublitz, W. (1999). Introduction: Views of coherence. In W. Bublitz, U. Lenk, & E. Ventola (Eds.), Coherence in spoken and written discourse: How to create it and how to describe it (pp. 1-10). Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.63.03bub.

Bygate, M. (2001). Speaking. In R. Carter & D. Nunan (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to teaching English to speakers of other languages (pp. 14-20). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667206.003.

Canale, M. (1983). From communicative competence to communicative language pedagogy. In J. C. Richards & R. W. Schmidt (Eds.), Language and communication (pp. 2-27). London, UK: Longman.

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, 1(1), 1-47.

Casamassima, M., & Insua, F. (2015). On how thinking shapes speaking: Techniques to enhance students’ oral discourse. English Teaching Forum, 53(2), 21-29.

Council of Europe. (2001). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Dontcheva-Navratilova, O., & Povolná, R. (2009). Coherence and cohesion in spoken and written discourse. Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars.

Edmondson, W. (1981). Spoken discourse: A model for analysis. London, UK: Longman.

Gass, S. M. (1997). Input, interaction, and the second language learner. Mahwah, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Gaudart, H. (1992). Persuading students to speak in English. Paper presented atthe first Malaysian English Language Teaching Association International Conference.

Geluykens, R. (1999). It takes two to cohere: The collaborative dimension of topical coherence in conversation. In W. Bublitz, U. Lenk, & E. Ventola (Eds.), Coherence in spoken and written discourse: How to create it and how to describe it (pp. 35-54). Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.63.06gel.

Guilloteaux, M. J., & Dörnyei, Z. (2008). Motivating language learners: A classroom-oriented investigation of the effects of motivational strategies on student motivation. TESOL Quarterly, 42(1), 55-77. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1545-7249.2008.tb00207.x.

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. A. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 70(2), 125-132. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1986.tb05256.x.

Hymes, D. H. (1972). On communicative competence. In J. B. Pride & J. Holmes (Eds.), Sociolinguistics: Selected readings (pp. 269-293). Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.

Krashen, S. D. (1982). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Oxford, UK: Pergamon Press.

Lazaraton, A. (2001). Teaching oral skills. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (3rd ed., pp. 103-115). Boston, US: Heinle & Heinle.

Littlewood, W. (1981). Communicative language teaching. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Littlewood, W. (2004). Students’ perspectives on interactive learning. In O. Kwo, T. Moore, & J. Jones (Eds.), Developing learning environments: Creativity, motivation, and collaboration in higher education (pp. 229-244). Hong Kong, HK: Hong Kong University Press.

Min, Y.-K. (n.d.). From the ESL student handbook by Young Min, PhD. Retrieved from http://www.uwb.edu/wacc/resources/esl-student-handbook/coherence.

Oxford, R. (2001). Language learning styles and strategies. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (3rd ed., pp. 357-366). Boston, US: Heinle & Heinle.

Parsons, R. D., & Brown, K. S. (2002). Teacher as reflective practitioner and action researcher. Belmont, US: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

Renkema, J. (2004). Introduction to discourse studies. Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/z.124.

Ritchhart, R. (2002). Intellectual character: What it is, why it matters, and how to get it. San Francisco, US: Jossey-Bass.

Ritchhart, R., Palmer, P., Church, M., & Tishman, S., (2006, April). Thinking routines: Establishing patterns of thinking in the classroom. Paper presented at the AERA Conference. Retrieved from http://www.ronritchhart.com/ronritchhart.com/Papers_files/AERA06ThinkingRoutinesV3.pdf.

Ritchhart, R., & Perkins, D. N. (2008). Making thinking visible. Educational Leadership, 65(5), 57-61. Retrieved from http://www.ronritchhart.com/ronritchhart.com/Papers_files/MTV_ritchhart_perkins.pdf.

Rickheit, G., Strohner, H., & Vorwerg, C., (2008). The concept of communicative competence. In G. Rickheit & H. Strohner (Eds.), Handbook of communication competence (Vol. 1, pp. 15-62). New York, US: Mouton de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110199000.

Savignon, S. J. (2001). Communicative language teaching for the twenty-first century. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (3rd ed., pp. 13-28). Boston, US: Heinle & Heinle.

Shumin, K. (2002). Factors to consider: Developing adult EFL students’ speaking abilities. In J. C. Richards & W. A. Renandya (Eds.), Methodology in language teaching: An anthology of current practice (pp. 204-211). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667190.028.

Tanskanen, S.-K. (2006). Collaborating towards coherence: Lexical cohesion in English discourse. Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.146.

Tsiplakides, I., & Keramida, A. (2009). Helping students overcome foreign language speaking anxiety in the English classroom: Theoretical issues and practical recommendations. International Education Studies, 2(4), 39-44. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v2n4p39.

Wang, Y., & Guo, M. (2014). A short analysis of discourse coherence. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 5(2), 460-465. http://doi.org/10.4304/jltr.5.2.460-465.

Wiśniewska, D. (2011). Mixed methods and action research: Similar or different? Glottodidactica, 37, 59-72. Retrieved from https://repozytorium.amu.edu.pl/bitstream/10593/1693/1/Wisniewska.pdf.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Zeus Plasencia Carballo. (2020). Elementos que intervienen en el éxito –y en el fracaso– de la interacción oral en lengua extranjera en secundaria. DIGILEC: Revista Internacional de Lenguas y Culturas, 6, p.14. https://doi.org/10.17979/digilec.2019.6.0.5425.

2. Mary Ann Meinecke. (2020). Identifying student preferences in online content and language integrated learning courses. DIGILEC: Revista Internacional de Lenguas y Culturas, 6, p.89. https://doi.org/10.17979/digilec.2019.6.0.5944.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

Copyright (c) 2018 PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.