Language Interaction Among EFL Primary Learners and Their Teacher Through Collaborative Task-Based Learning

Interacción del lenguaje entre estudiantes y su docente en el contexto del aprendizaje de la lengua extranjera basado en tareas

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v20n2.63845Keywords:

Collaborative learning, interaction, language interaction (en)aprendizaje colaborativo, aprendizaje de la lengua extranjera, interacción de la lengua (es)

This article focuses on research carried out in a private school in Bogotá with a group of English as a foreign language fourth-graders. The study aimed to analyze interaction in the English classroom through action research, based on tasks that promoted collaborative work and involvement of the students and their teacher. The instruments to collect data were video recordings and artefacts from the students’ tasks in the classroom. The analysis of classroom interaction involved the steps of conversational analysis stated by Seedhouse (2004). The study allowed the description of unexpected patterns of interactions among students and their teacher, which revealed changes in the classroom dynamic as a result of the action research plan.

Language Interaction Among EFL Primary Learners and Their Teacher Through Collaborative Task-Based Learning

Interacción del lenguaje entre estudiantes y su docente en el contexto del aprendizaje de la lengua extranjera basado en tareas

Ingrid Rocío Suárez Ramírez*

Sandra Milena Rodríguez**

Universidad Santo Tomás, Bogotá, Colombia

*ingridsuarez@ustadistancia.edu.co

**sandramilenarodriguez@ustadistancia.edu.co

This article was received on April 2, 2017 and accepted on February 9, 2018.

How to cite this article (APA, 6th ed.):

Suárez Ramírez, I. R., & Rodríguez, S. M. (2018). Language interaction among EFL primary learners and their teacher through collaborative task-based learning. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 20(2), 95-109. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v20n2.63845.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This article focuses on research carried out in a private school in Bogotá with a group of English as a foreign language fourth-graders. The study aimed to analyze interaction in the English classroom through action research, based on tasks that promoted collaborative work and involvement of the students and their teacher. The instruments to collect data were video recordings and artefacts from the students’ tasks in the classroom. The analysis of classroom interaction involved the steps of conversational analysis stated by Seedhouse (2004). The study allowed the description of unexpected patterns of interactions among students and their teacher, which revealed changes in the classroom dynamic as a result of the action research plan.

Key words: Collaborative learning, interaction, language interaction.

Este artículo presenta los hallazgos de una investigación llevada a cabo con estudiantes de cuarto grado de primaria en un colegio de Bogotá. El objetivo principal fue analizar la interacción en las clases de inglés como lengua extranjera. El diseño investigativo responde a la investigación-acción y los instrumentos utilizados para obtener información fueron grabaciones audiovisuales y la producción de tareas, resultado de los talleres elaborados en clase por los estudiantes. Los datos se analizaron a través del análisis conversacional de Seedhouse (2004). El problema planteado permitió describir patrones inesperados en las interacciones entre los estudiantes y su docente, los cuales revelaron cambios en la dinámica del salón de clase.

Palabras clave: aprendizaje colaborativo, aprendizaje de la lengua extranjera, interacción de la lengua.

Introduction

The research was carried out in a private school in Bogotá during eight sessions in an English as a foreign language (EFL) classroom with fourth graders. At the beginning of the study, learners were reluctant to participate in the English class and conflicts were part of their everyday classroom routines since they preferred to work alone. These situations affected negatively the learners’ interest and their response to working collaboratively. All this created a bad environment within the English classroom.

The aforementioned tensions and the continuous observations done by the teacher in the classroom provided information related to the students’ lack of participation and interest. Hence, the teacher expected to understand what occurred in class, but also to find ways to deal with difficulties in class. This research applied the stages proposed in an action research cycle (Burns, 2010) which, on the one hand, aimed at fostering interaction among students and on the other hand, proposed to understand why students and the teacher behaved the way they did it. Therefore, the research focused on social interaction in relation to the English learning process. As mentioned above, the challenge was also to create a scenario in the classroom that could respond to the students’ positions since they were bored and discouraged about their English classes.

As the research aimed at understanding how students and the teacher interacted, eight tasks were implemented with the intention of changing the dynamics of the English classroom by promoting collaborative work to make evident how interactions occurred between the participants aforementioned.

In this respect, it was necessary to record all classes to revise in detail what occurred during each implementation, bearing in mind verbal and nonverbal interactions. Moreover, the students’ artefacts like posters, cards, worksheets, oral presentations, puppets, and models were collected and analyzed too.

The conversation analysis approach allowed researchers to interpret the data collected (Seedhouse, 2004). Then, the results contributed to promote changes in the English classes.

The research design included pedagogical interventions focused on identifying aspects related to language interaction through eight collaborative tasks to understand how to promote interaction in the classroom. Furthermore, this provided elements to encourage students to make use of the target language in a different way.

Theoretical Framework

The main constructs that support the study correspond to interaction and its relationship with the foreign language, classroom interaction, collaborative learning and the definition of tasks, which were the basis of the pedagogical intervention in doing the action research plan.

Interaction

Nunan (2004) understands interaction as a social perspective of language because students can infer the meaning of what they say in class. Sometimes, they make mistakes or modify linguistic forms of English, but they can convey meaning. This lets students construct different ways to communicate in verbal or nonverbal ways.

In addition, students’ behavior is consciously reorganized and influenced by the participants in class in a continuous cycle while they interact. Turner (1988) sustains that “behavior” is understood as the way students react when they communicate.

Likewise, Seedhouse (2004) establishes interaction as a set of processes among two or more students participating to convey meaning while they sustain their own conversations following a common goal. Holliday (1994) sustained that there is a strong connection between classroom dynamics and social interaction. Furthermore, previous research done by Riascos (2014) and Riveros (2012) agreed that it was difficult for the students to learn a foreign language because of the lack of interaction and appropriate environment that surrounds teachers and students in class. The classroom is, then, a scenario where the teacher and students react and assume roles and positions in their classroom. This perspective about interaction centered the classroom as a controlled micro-society understanding the classroom as a research scenario.

Language Interaction

Language interaction is the way in which teachers and students are immersed in the classroom to construct their own reality; hence, this highlights the different reactions that students and the teacher presented during the instructional process (Nunan, 2004).

It also implies going beyond communication to establish a set of pedagogical actions in order to provide opportunities to encourage students’ participation and to reduce anxiety. When participants in the class make use of the foreign language, different interaction patterns take place: student-student, teacher-student, student-teacher, and student-learning context. Student-student interaction involves positions and roles evidenced among students in class.

Bronfman and Martinez (1996) define relationships among classmates as horizontal interaction. Although positions and roles were identified among students in the classroom, learners conveyed meaning through agreements to fulfill the collaborative tasks proposed during the classes.

Collaborative Learning

According to Nunan (2004), task-based language teaching (TBLT) considers learning as a process where learners have the opportunity to focus on a language learning target through real situations in the classroom. Thus, the study followed the stages proposed by Nunan (2004) to design and implement the pedagogical tasks aimed at providing more and new opportunities to accomplish the research objective and also to enrich the pedagogical plan.

Each one of the tasks of the pedagogical implementation followed the next three steps: In the first one, activation process, the eight tasks were designed based on language interaction and involved simultaneously a continuous reflection to determine the sequence of the tasks and their impact on the learning process. The second one, called enabling skills, focused on collaborative learning goals to enhance and provide more scenarios for the students to interact based on established pedagogical goals and the third one, called language outcome, implied that at the end of each task, the fourth graders shared and presented their oral or written productions resulting from the interaction and collaborative work done through steps 1 and 2.

Research Design

This research followed the qualitative paradigm described by Hancock, Ockleford, and Windridge (2009), who characterized qualitative research as a manner to understand the way we are in our social world. Hence, this reinforced the vision of this research process by considering the students’ interactions as a central role in the classroom. Accordingly, the stages to reflect upon the aforementioned elements were followed by an action research methodology.

This action research cycle took nine months. During this time a didactic unit was designed including topics based on students’ interests but also on the school’s syllabus. The sessions in the classroom were recorded and then transcribed. The implementation of the TBLT approach stated the importance of collaborative learning providing students with new and vivid learning experiences in the English classes.

Figure 1 shows the eight pedagogical interventions. These sessions were initiated with the identification of the learners’ necessities in the English classroom and ended with the complete involvement of students with the proposed tasks for working collaboratively. Each task followed the four stage cycle: planning, acting, observing, and reflecting (Burns, 2010). As a result of the cycle proposed by Burns, it was feasible to observe and analyze what occurred in the classroom in terms of interaction, but also to make better informed decisions to provide solutions to difficulties evidenced in the classroom.

Figure 1. Tasks Implemented

Pedagogical Actions

In order to improve students’ active involvement in the classes, two teaching actions were included. The actions consisted of (a) defining one theme and a unit coherent with students’ interests, needs, and the school’s syllabus; and (b) implementing the TBLT approach through the development of eight tasks to observe how interactions occurred in class. In this way, each implemented task had a research objective and a pedagogical one. This means that each class was designed thinking about how to foster collaboration and describe interaction among learners and their teacher.

Putting the Pedagogical Plan Into Action

At the beginning of the study, the first session had three intentions: (a) talking about learners’ last vacation trip, (b) collecting data about the learners’ previous knowledge, and (c) comparing data to list students’ interests and conflicts inside the classroom. Once their interests and difficulties were clearly identified, seven tasks were designed to fulfill students’ necessities and interests, but also to promote interaction in the English classroom.

Observing the Results of the Plan

This step implied for the researchers to revisit each implementation to determine the design of the next task. Video-recordings were observed and transcribed with the purpose of identifying how the participants of the study interacted in the classroom, which means a continuous observation of the pedagogical intervention and the research process.

Reflecting for Planning Actions in the Classroom

As this research focused on interaction, all the different issues that were problematic or challenging were given special attention while implementing the tasks. This step implied understanding what happened in the classroom so data collection could allow researchers to identify common interaction patterns during the eight implementations and make decisions about the action research cycle.

Context and Participants

A group of 22 boys and 17 girls from 8 to 12 years old from a private school located in Bogotá participated in this study. At the beginning of the research, students faced difficulties in terms of language learning and such problems had to do with their own social interaction and conflicts in their English classroom. The interest in identifying and solving social conflicts make up part of the aims established by the school.

The institution receives students who cannot afford their fee thus they are supported with scholarships, which means that some of the research participants come from diverse social and cultural backgrounds. When conflicts and social differences make up part of the classroom, such as the context of this study, the institution focuses its attention on these situations and encourages teachers to mediate and address such conflicts among students.

The authors of this article are the English teacher of 4th grade in a private school in Bogotá who carried out the pedagogical intervention and the supervisor of the research, who guided and advised the different pedagogical strategies during the eight implementations, here presented as a co-author.

Data Collection Instruments

The research question focused on the identification of language interaction and how it occurred in the group of 4th grade students when interacting collaboratively. It was necessary to record students’ attitudes and interactions during the development of collaborative tasks. Therefore, the instruments to gather data were: (a) around 450 minutes of video recording and (b) students’ artefacts comprised of posters, written texts, cards, worksheets, and students’ oral presentations.

Video-Recordings

Videos captured naturalistic interactions and verbatim utterances (Burns, 2010). The instrument was used to identify verbal and nonverbal interaction to see what happened in class. Burns (2010) also expresses that “recording the situation you want to observe has the advantage of capturing oral interactions exactly as they were said” (p. 70). As the author recommends, observations should focus on interactions during the development of the tasks.

Artefacts

Artefacts corresponded to the students’ productions (written, oral, visual, manual products), which also revealed how language interaction occurred during the implementation of tasks. Evidences of classroom interaction were revised and analyzed under the methodology of conversational analysis.

Criteria and Steps to Analyze Data

As proposed by Seedhouse (2004), conversational analysis allowed researchers to identify what happened and resulted in participants’ interactions being enhanced in class, because it enabled one to figure out verbal and nonverbal interactions. This methodology proposes five steps:

- Unmotivated looking. It requires discovering patterns of the phenomena. It means to transcribe all the information recorded because everything could be important.

- Inductive search. It involved the analysis of data to identify common situations that caught the researchers’ attention.

- Establish regularities and patterns which implied determining what emerged from interactions among participants.

- Detailed analysis of single instances of the phenomenon. It allowed researchers to be observant and sensitive when studying language interaction.

- A more generalized account, which corresponds to the study of actions behind interaction among the students and their teacher. It implied describing what happened in the context considering how interaction occurred. For the transcriptions, this analysis used the conventions proposed by Seedhouse (see Appendix).

Findings

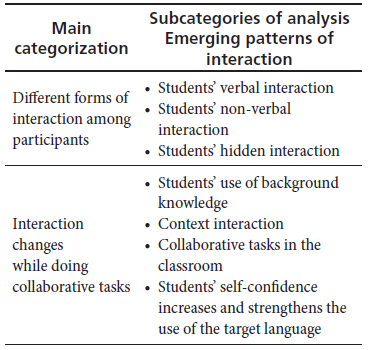

The exchanges presented by the teacher and learners in class were analyzed under the methodology of conversational analysis. The transcription of excerpts and the artefacts completed by the students in each implementation provided findings in terms of the participants’ behavior and the way they established relationships among each other. Seedhouse (2005) explains how the participants’ behavior shows interactional principles that reveal how students understand each other and make sense of their own interactions in the classroom. Table 1 shows the categories that emerged through the study in class.

Table 1. Main Categories and Patterns of Interaction

Different Forms of Interaction Among Participants

This first finding revealed three ways participants adopted in class through verbal, nonverbal, and hidden interaction.

Students’ Verbal Interaction

Learners used their mother tongue as a vehicle to construct paths of communication. Excerpt 1 evidences this finding. This demonstrates how the use of the mother tongue is vital in the teacher and students’ utterances to maintain spoken interaction to convey meaning.

Excerpt 1

The teacher is brainstorming about concepts related to “exciting trips”.

- T:1 what do you think it is exciting trips? [Immediately, three or four students raised their hands to express their opinions]

- T: OK. Remember that you need to raise your hand to give your opinion. OK. [The teacher gave the turn to S10]

- S10: Exciting trips?!!!(..)

- S9: (.......)

- T: OK tell me.

- S10: Rules?

- T: OK? Rules. What else?

- S10: Expressions.

- T: Expressions (....). OK. If I add this keyword: vacations [In that moment the teacher wrote that word on the board]

- S12: Vacations ((Vacaciones!!!!!))(......)

According to Yufrizal (2001) in an EFL setting learning occurs mostly within the classroom while the target language is encouraged in class through tasks that play a very important role in determining the rate of language learners’ involvement in interaction and negotiation of meaning. The next subcategory depicts how the students and also the teacher in the fourth task decrease the use of their mother tongue to implement other ways to interact and convey meaning.

Students’ Non-Verbal Interaction

The analysis of transcriptions demonstrated that the teacher and students used new forms to convey meaning through the use of non-verbal language as Excerpt 2 shows.

Excerpt 2 (Taken from Session 4)

Students solving a task proposed by the teacher.

- S26: What do you have?

- S6: [Showed the paper and S26 began to produce sounds]

- S26: Ow...Aww

Excerpt 2 revealed how students used gestures and body movements to avoid the overuse of the mother tongue especially on the fourth task. According to Pica (1996) interaction occurs when the flow of the learner’s message with the interlocutor is restructured and modified by requests and responses. It provides new ways to comprehend a message.

Furthermore, during the pedagogical intervention, it was noticed by the researchers that students avoided backchannels. As resources of interaction students used gestures, facial expressions, and body language. In this sense, non-verbal language emerged as a form of interaction in the classroom. It was also a source for the teacher to keep in touch with the students.

Students’ Hidden Interaction

This finding uses the word “hidden” because it reflected an unexpected kind of interaction identified during the study. This hidden interaction only occurred among boys and girls without involving directly the teacher. At the beginning of the study, learners were reluctant to participate because they were not confident in using the target language and they found it difficult to work with each other, especially when they had to work in mixed (boys and girls) groups. However, the classroom scenario changed from working individually to working in groups as a consequence of the implementation of the proposed tasks.

In fact, conflicts between boys and girls affected the way they reacted towards the collaborative tasks. In this sense, different positions and roles took place in the classroom. Hollway (as cited in Castañeda-Peña, 2008) states how masculinities and femininities affect the exchanges students have in an English class in an EFL setting: “First, there is an incontestable difference between males and females. Second, there are differences that could be negotiated. Third, ‘things’ performed by the other sex are important and valuable and could be taken up by the opposite sex” (p. 316).

Also, Bronfman and Martinez (1996) designed the metaphor “la cara oculta de la Luna” (the hidden face of the Moon) to explain the complexity about interactions among students. These interactions mediated by students’ intersubjectivities and their power relationships emerge in a different kind of interaction denominated horizontal interaction. It makes reference to the changes in the role of the students that depend on the level of authority conditioned, not essentially by the teacher in the classroom, but conditioned by the subgroups of students that position power as establishing relationships in a classroom.

Conflicts among boys and girls affected the classes negatively and guided the researchers to consider such tensions in the classroom in carrying out the pedagogical implementation. To illustrate this point, the fourth task called “Helping aliens to solve problems” was crucial to reduce conflicts. This task had three objectives: (a) to make learners reflect on conflicts, (b) to identify how interactions occurred through its implementation, and (c) to promote the use of the target language through collaborative work.

In this way the fourth task invited students to reflect upon these three questions: (a) How did you feel during the last task? (b) Did you complete the task? (c) What can you do as a learner to collaborate and improve during the classroom work?

After reflecting, students received instructions to work in groups of five people, but this time the groups were organized by the teacher with the intention to mix them and break down power relationships. Then, they received a worksheet in which the teacher presented four problematic situations that aliens had to face in the school of planet Pluto.

The teacher recreated four aliens who had to face the following problems: Alien 1 did not finish the activities proposed in class; Alien 2 was a girl and male aliens did not play or share with her; Alien 3 did not like to play football so his classmates separated him from their groups; Alien 4 liked to play football, but since he wasn’t capable of playing well his classmates pushed him aside.

Once the students wrote different pieces of advice to help aliens to solve the problem, the teacher asked students if one of those situations occurred in the class. Excerpts 3 and 4 illustrate some of the answers provided by the students in the aforementioned task during the class:

Excerpt 3

Student’s reflection after the development of task 7

- T: How was the activity? ((¿Cómo les fue acá?))

- S24: We have already talked about it. ((Ya dialogamos))

- T: What did you figure out? (¿Y con qué se encontraron?))

- S24: We found that we have the same problems here in class. ((Con que sí, todo eso pasa))

- S1-S20: Yes, especially those boys refuse to share with us. ((Sí, pasa lo del rechazo))

- S24: To them yes. It doesn’t happen to me. ((A ellas sí (1s) a mí no))

- S1-S20: That’s what you think. ((Sí, como no)

- S20: All the problems occur here. ((Todos los problemas que tienen allá suceden acá))

- S20: Some occur here but some of them occur especially in class. ((Algunos pasan acá pero algunos en especial sí pasan en el salón))

- T: Like which? ((¿Cómo cuáles?))

- S1: That we don’t finish our activities. ((El de no terminar las tareas))

- S20: That some boys don’t accept us, for example when they play football. ((El de los hombres, algunos no nos aceptan a nosotras, cuando juegan por ejemplo. fútbol) (a)

- T: But S24 is working with you and he is doing it greatly.(b) ((Pero S24 está trabajando con ustedes y está trabajando espectacular))

- S20: Well, S24 no but S27 and S31 yes.(a) ((Ah, no pues S24 no)) ((Pero sí lo decimos por ejemplo por, S27 ehh S31))

- S24: It’s true. (c) ((Es verdad))

- S19: ((Pero les damos un balonazo y salen por allá a la enfermería)) ((Ah no)) (Y ustedes hacen así) (The student began moving his body explaining that the girls could be hurt if they played soccer)) ((Y las manda uno por allá al quinto chorizo)) (and we put you girls aside, far away from us)

- S24: Well, what do we have to do? ((¿Bueno ahora sí que tenemos que escribir?))

Excerpt 4

This is an answer written by a student (girl) in a workshop (artefact).

The teacher asked the students if they liked to participate in class.

S19: No, because there are some classmates who mock me. ((No, porque hay compañeros que se ríen cuando me equivoco))

These excerpts demonstrate how students had their own conflicts and differences in their interactions and how these affected the way they reacted in class. Turner (1988) states that students’ reaction to the language learning process is deeply rooted in the personality and experience of each learner. Furthermore, students’ interactions with the learning process arise out of complex attitudes, which are specific to each individual. Excerpt 4 makes evident how their differences affected the way girls and boys participated in class.

Thus, Excerpt 3 describes how language interaction made explicit masculinities and femininities defined by Castañeda-Peña (2008). A girl (S20) affirms that some boys do not accept girls for playing soccer and indeed one of the boys (S19) explains that he cannot play soccer with girls because such acceptance creates conflicts with the other boys in the English classes. Also, students use a code mediated by their attitudes, rules, and values. Holloway (as cited in Castañeda-Peña, 2008) states that “values attach to a person’s practices and provide the powers through which he or she can position him or herself in relation to others” (p. 317).

Interaction Changes When Doing Collaborative Tasks

Findings related to collaborative tasks show how students established a relationship with their prior knowledge when doing the tasks and interacting in the classroom.

Students’ Use of Background Knowledge

This subcategory indicates the connection of the students with their background knowledge and the interaction with the target language in the classroom while completing the tasks proposed by the teacher.

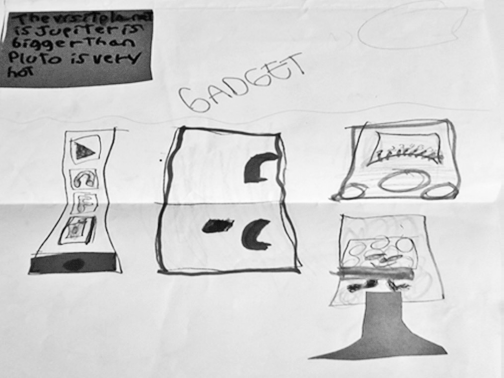

Upon revisiting artefacts, the finding of Figure 2 emerged which evidences the connections students made between the proposed task and their background knowledge. Yule (2008) explains that the “ability to arrive automatically at interpretations of the unwritten and unsaid must be based on pre-existing knowledge structures called background knowledge” (p. 85). This pre-existing knowledge is connected with what the student did in the classroom.

Figure 2. Student’s Artefact

Context Interaction

As Turner (1988) proposes, the classroom is an event in which actions and interactions will be developed to implement the ideas proposed in a lesson. The artefacts in Figures 3 and 4 illustrate how students completed the tasks according to the situation proposed by the teacher.

Figure 3. Student’s Artefact

Figure 4. Puppets Artefact Done by Students

Figure 3 illustrates how students were involved in an activity that implied the creation of gadgets to take to space and help a group of aliens solve problems, which intentionally were presented by the teacher in the classroom with the purpose of having learners reflect upon their own situations and conflicts in class. In addition, Figure 3 shows one of the posters designed by a group of students. The task aimed to foster group interaction. While doing the posters, students engaged collaboratively with the development of the task. After completing the task, students received the instruction to create puppets as seen in Figure 4 to represent aliens.

The puppets were useful for the learners to interact and express their own feelings about the themes presented within the class. The names of the tasks were: “helping aliens solve problems” and “life on Pluto”. Excerpt 5 depicts the context that recreated the connection between the aliens and the learners:

Excerpt 5

As aforementioned, through Task 7 students were asked to advise aliens about some problems that they had to face in their class on Pluto (those situations were similar to the situations that they presented in their English classes). As they only spoke English their advice had to be in English. In, Task 6 the teacher presented the students the alien’s responses and this was the reaction of one of the groups.

- S19: Teacher is (0.2s) what? (0.1) the alien did not understand (The student pointed to the alien’s answer presented by Alien 3) you see (0.2 s) he says that he didn’t understand our advice and we told him to talk.

- T: Alien says that he can’t talk.

- SS: (0.2 s) (S19 nodded his head) oh! (student looked worried)

Excerpt 6

The teacher and students were giving feedback about an activity they had already done.

- T: (The teacher read the material) Oh. He doesn’t like soccer (a)

- S30: (b) oh no!

- T: but how?

- S30: PSs’

- T: But how? I don’t like mmm No advice

- S35: Poor Curly!

When reading Excerpt 6, students demonstrated feeling affectively connected with the process since they expressed feeling worried about the difficulties that aliens had to face on the planet Pluto. In this sense, Holliday (1994) states: “The classroom is part of interrelated and overlapping cultures of different dimensions within the host educational environment” (p. 28). In such a manner, this author proposes that each class has its own characteristics. The study evidenced that students engaged with the problem situations proposed by the researchers.

Collaborative Tasks in the Classroom

Changes describe what occurred during the implementation of tasks in the classroom on which collaborative learning constituted an important part of the study. The researchers established a link between the pedagogical aims and the proposed organization of collaborative work to increase the capacity of learners to negotiate agreements, to convey meaning and complete the tasks by working in groups.

Excerpt 7 is an example of how learners constructed support and meaning while working collaboratively. In this task students needed to make an oral presentation. For doing so, the teacher let them organize in groups. Then, they made a poster and finally, they described the places that they liked the most on their last vacations. The aim was to foster interaction.

Excerpt 7

Students’ agreements on an oral presentation

- S27: I like to Caño Cristales.

- S7: I like to Parque San Agustín.

- S27: I need to the travel ahh (...) backpack, money, camera, mmm (....).

- S19: I like to Planetario

- S39: I like to the Amazonas.

- T: Please everybody. Sit down and silence.

- T: OK. Sit down.

- S27: I need to the travel bloqueador (sunblock)....

- S19: Camera, money, and (....) and (....) Bueno (well).

- S39: I need to the travel como (how) ... (xxx) Like the bike to Zipaquirá.

- S7: What...do you need to travel? Ehhh. Bloqueador, ropa....(.....) ya. (sunblock, clothes...that’s it) I like to Rio Amazonas. I need bloqueador, repelente, (sunblock, repellent) ehh (....) ropa y (clothes and) family....

- T: y Family. Jejeje. [Laughs] Necesito mi familia muy bien. (I need my family)...Very good! Listo (ready). Something else?

- S7-27: No.

- T: OK, sit down.

Excerpt 7 demonstrates how interaction agreements play an important role in determining negotiation of meaning. Additionally, body language and students’ mother tongue supported their interaction: When one student did not know what to say, non-verbal interaction resulted effective to complete the tasks. Pica (1996) affirms that tasks play an important role in determining the rate of language learning in interaction and negotiation of meaning.

The implementation of collaborative tasks in the study aimed at enriching the students’ learning process through themes that were familiar and related to the students’ interests; for example, the tasks about vacations, aliens, and gadgets to travel. There was an intention in the study to include themes that could be close to the learners’ preferences to foster confidence while using English within the classroom.

Students’ Self-Confidence Increases and Strengthens the Use of the Target Language

Through interaction, students showed more appropriation of target language while interchanging information with their teacher. Excerpts 8, 9, and 10 illustrate how interaction occurred between the students and their teacher in relation to their oral presentation and description about planet Pluto:

Excerpt 8

Student asked the teacher about planet Pluto:

- S34: What is the color the Pluto?

- T: What is Pluto’s color? (...) Imagine [The teacher smiled]

- S34: Thank you.

Excerpt 9

During the students’ oral presentation.

- S27: Ahhh... t’s a little planet. [He touches S21 to tell him that it’s his turn]

- S21: Is.... Is ..... Is..... (4s)

- S19: Satélite (satellite) goes to the Pluto. The Pluto is more small.

- S10: [He breathes before speaking] the xxxx tiene (has) five moons [Then, he looks at S31]

- S31: Pluto is very smaller than the earth and tiene (has) moons.

- S11: Pluto is small..... (.....) Five moons.

- T: OK. Something else? OK go sit down.

Excerpt 10

Another group presenting an exposition.

- S17: Ehhh...This is Pluto. This planet is very small than earth y.... [Then, he looks other classmate to give the turn]

- S26: The spaceship was more (xxxx) .... (xxx) This is Pluto’s.

- T: OK.

- S7: Pluto is a very very...very small planet. He has a (2s) five moons ah small moons and it’s very beautiful.

- T: OK, finish. OK. Put it on the floor (....) put it on the floor. Put it on the floor. [The teacher points out with her finger] Good!

Students gained understanding and self-confidence while using the foreign language as the excerpts above demonstrate. In Excerpt 8, one of the students S34 proved to be more confident to using English while asking the teacher for information about the color of Pluto. The purpose of Excerpts 8, 9, and 10 was to illustrate explicit evidences of how learners showed their use of the foreign language while the implementation of tasks took place through the study.

Seedhouse (2004) claims that repair is also a mechanism of self-confidence when using the language. Students learn to repair breakdowns in communication. This enriches the language learning process since gaining self-confidence give students the opportunity to support their own interaction and achieve the proposed tasks in the classroom.

Moreover, their capacities to reach goals standing and speaking in front of their partners, making decisions, or just expressing themselves among them is also another bit of evidence of how students strengthened interaction:

Excerpt 11

Students interacting as participating in the puppet play.

- T: OK. This is the final production. So, respect your partners OK?

- T: One (c)

- S24: two, three.

- S17: Hello. My name, my first name is Mini Kick. My father is Sidesick and my mother is a Minion! (5s)

- S23: Hello. How you are in Pluto?

- S27: (Curly) I’m have a big problem. You can resolve this? (5s)

- S31: (Drakcraft) Yes, I can.

- S27: (Deviant) I didn’t play with my alien’s friends and my problem is my parents don’t accept me.

- S26: I’m very bad playing soccer.

- S31: (Drakcraft) OK, I can solve this.

- S27: (Deviant) and my problem you can resolve this.

- S27: (Deviant) What’s happen?

- S27: (Curly) Nothing!

- S31: OK, man. Share with your parents.

Excerpt 11 demonstrates how students increased their participation, became more active, and had an important influence on changes in the students’ role and the classroom dynamics. At the end of the study, the teacher perceived that students were more independent and responsible while doing the tasks. Learners were more supportive as upon hearing the teacher’s decisions they modified the way they interacted by having more collaborative attitudes in their classroom.

Conclusions

As the main goal of this study was to describe how language interaction occurs through collaborative TBLT among EFL primary learners and their teacher; it was necessary to have in mind the concept of “interaction as a social act” (Seedhouse, 2004). In other words, the exchanges presented by teacher and learners in class let them analyze through conversational analysis methodology the interactions that emerged among the teacher and the students.

In this sense, findings and patterns of interaction described how learners are also social actors that transform and establish agreements to participate in and activate their learning process in the way the teacher involves them. It meant that the action research plan also allowed researchers to determine the necessity to understand students’ interests to recreate the classroom as a scenario of interaction.

As data analysis was based on conversation analysis proposed by Seedhouse (2005), the recorded excerpts considered interaction as a social act, from which different forms of interaction emerged: verbal, non-verbal, use of their mother tongue. Also, the code or the way students interacted is mediated by students’ attitudes, rules, and values.

Another element was the students’ reaction when the classroom scenario was changed. As researchers we found that learners’ social interaction in an EFL setting improved the classroom scenario in two aspects: their confidence with the use of the language, but also the way they interacted with the context and among themselves. About students’ attitudes and reactions, they were reluctant at the beginning of the study to work in groups and this position was reshaped through the effect of the pedagogical intervention and the encouragement of collaborative learning. Students realized that they needed to achieve the same goal; this fact changed the role of participants in the classroom including the role of the teacher.

Moreover, students became more participative at the end of the study. They showed more responsibility in making decisions and developing collaborative tasks. All the aspects mentioned throughout this research demonstrated how they interacted with more confidence and appropriation in using the foreign language.

It was necessary to make precise and accurate decisions to promote collaborative work. It was the way to guide students to interact in a different way in the classroom. The research provided the researchers a different perception about classroom management. The first one, the exchanges among students in the classroom. The second one, as researchers we could evidence that tasks connected with the students’ daily situations made them more confident and engaged with their own language learning process.

The way language interaction occurs through collaborative TBLT among EFL primary learners and their teacher revealed how learners use their mother tongue and nonverbal language to convey meaning. Also, the encouragement of interaction and collaborative work changed the role and position that students had at the beginning of the study.

Another interesting point was the role of the research supervisor, since the study constituted a possibility to investigate collaboratively with the teacher of the students who participated in the research. In that way, the pedagogical intervention and the analysis of findings through conversational analysis made possible an academic collaboration that provided a new understanding about language interaction, the importance of focusing on power relationships and social conflicts in the classroom, which re-signified the role of being language teachers and researchers in educational contexts.

1The codes for the excerpts are T = Teacher. The students are coded with an S followed by a number (e.g., S1, S2, S3).

References

Bronfman, A., & Martinez, I. (1996). La socialización en la escuela: una perspectiva etnográfica. Barcelona, ES: Paidós.

Burns, A. (2010). Doing action research in English language teaching: A guide for practitioners. New York, US: Taylor & Francis.

Castañeda-Peña, H. (2008). Positioning masculinities and femininities in preschool EFL education. Signo y Pensamiento, 27, 314-326.

Hancock, B., Ockleford, E., & Windridge, K. (2009). An introduction to qualitative research. Retrieved from https://www.rds-yh.nihr.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/5_Introduction-to-qualitative-research-2009.pdf.

Holliday, A. (1994). Appropriate methodology and social context. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Nunan, D. (2004). Task-based language teaching. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667336.

Pica, T. (1996). The essential role in negotiation in the communicative classroom. JALT Journal, 18(2), 241-268.

Riascos, Y. I. (2014). Exploring TBL and teaching in light of recent developments in online internet tools (Undergraduate monograph). Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá.

Riveros, F. Q. (2012). Cómo pueden los profesores de EFL lograr un aprendizaje más efectivo a través de la implementación y evaluación de estrategias basadas en el aprendizaje cooperativo (Undergraduate monograph). Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá.

Seedhouse, P. (2004). Conversation analysis methodology. Language Learning, 54(s1), 1-54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2004.00268.x.

Seedhouse, P. (2005). Conversational analysis and language learning. Language Teaching, 38, 165-187. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444805003010.

Turner, J. H. (1988). A theory of social interaction. Stanford, US: Stanford University Press.

Yufrizal, H. (2001). Negotiation of meaning and language acquisition by Indonesia EFL learners. TEFLIN Journal, 12(1), 60-87.

Yule, G. (1996). Pragmatics. New York, US: Oxford University Press.

About the Authors

Ingrid Rocío Suárez Ramírez has been an English teacher for over seven years. She holds a bachelor in English as a foreign language from Universidad Santo Tomás, Bogotá (Colombia) and is currently studying for an MA in the teaching of foreign languages with an emphasis in English at Universidad Pedagógica Nacional (Colombia).

Sandra Milena Rodríguez is a teacher at Universidad Santo Tomás, Bogotá (Colombia). She holds a bachelor of philology and languages from Universidad Nacional de Colombia and a Master in education from Universidad Santo Tomás.

Appendix: Codes for the Transcriptions (Seedhouse, 2004)

These are the symbols we implemented to transcribe the recorded classes:

[ Point of overlap onset.

] Point of overlap termination.

(b) If inserted at the end of one speaker’s turn and at the beginning of the next speaker’s adjacent turn, indicates that there is no gap at all between the two turns.

(.) Very short untimed pause.

, Low-rising intonation, suggesting continuation.

. Falling (final) intonation.

< > Talk surrounded by angle brackets is produced slowly and deliberately (typical of teachers modeling forms).

( ) A stretch of unclear or unintelligible speech.

(guess) Indicates the transcriber’s doubt about a word.

References

Bronfman, A., & Martinez, I. (1996). La socialización en la escuela: una perspectiva etnográfica. Barcelona, ES: Paidós.

Burns, A. (2010). Doing action research in English language teaching: A guide for practitioners. New York, US: Taylor & Francis.

Castañeda-Peña, H. (2008). Positioning masculinities and femininities in preschool EFL education. Signo y Pensamiento, 27, 314-326.

Hancock, B., Ockleford, E., & Windridge, K. (2009). An introduction to qualitative research. Retrieved from https://www.rds-yh.nihr.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/5_Introduction-to-qualitative-research-2009.pdf.

Holliday, A. (1994). Appropriate methodology and social context. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Nunan, D. (2004). Task-based language teaching. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667336.

Pica, T. (1996). The essential role in negotiation in the communicative classroom. JALT Journal, 18(2), 241-268.

Riascos, Y. I. (2014). Exploring TBL and teaching in light of recent developments in online internet tools (Undergraduate monograph). Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá.

Riveros, F. Q. (2012). Cómo pueden los profesores de EFL lograr un aprendizaje más efectivo a través de la implementación y evaluación de estrategias basadas en el aprendizaje cooperativo (Undergraduate monograph). Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá.

Seedhouse, P. (2004). Conversation analysis methodology. Language Learning, 54(s1), 1-54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2004.00268.x.

Seedhouse, P. (2005). Conversational analysis and language learning. Language Teaching, 38, 165-187. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444805003010.

Turner, J. H. (1988). A theory of social interaction. Stanford, US: Stanford University Press.

Yufrizal, H. (2001). Negotiation of meaning and language acquisition by Indonesia EFL learners. TEFLIN Journal, 12(1), 60-87.

Yule, G. (1996). Pragmatics. New York, US: Oxford University Press.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Paola Julie Aguilar Cruz, Mónica Fernanda Garrido-Yagüe, Pablo Emilio Rodulfo-Elizalde. (2025). Pre-service Teachers’ Perspectives on Materials Development. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 27(1), p.47. https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.20635.

2. Jean Kaya, Alba del Carmen Olaya León, Pedro Felipe Ortega Prieto, Catalina Toro Mejía . (2025). Language Pedagogies in Colombian English Classrooms: A Systematic Review of Literature from Colombian Journals. Enunciación, 30(2), p.245. https://doi.org/10.14483/22486798.23312.

3. Elaine Riordan. (2025). Handbook of Language Teacher Education. Springer International Handbooks of Education. , p.621. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-47310-4_17.

4. Gaili Cui. (2025). Analyzing the Influence of Task-Based Teaching Method on Students’ Language Proficiency Enhancement in College English Teaching Based on Big Data. Applied Mathematics and Nonlinear Sciences, 10(1) https://doi.org/10.2478/amns-2025-1060.

5. Elaine Riordan. (2024). Handbook of Language Teacher Education. Springer International Handbooks of Education. , p.1. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-43208-8_17-1.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

Copyright (c) 2018 PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.