Integrating Assessment in a CLIL-Based Approach for Second-Year University Students

Incorporación de la evaluación basada en el aprendizaje integrado de contenidos y lenguas extranjeras para estudiantes universitarios de segundo año

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v20n2.66515Keywords:

Assessment, content and language integrated learning, linguistic awareness, oral production, rubric (en)aprendizaje integrado de contenidos y lenguas extranjeras, conciencia lingüística, evaluación, producción oral, rúbrica (es)

This article examines the intervention, through the design and pedagogical implementation of two rubrics based on theory from the Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) approach, to assess the oral competences in English of a group of sophomores in a content subject. The data collection and subsequent analysis included both quantitative and qualitative sources to evaluate students’ oral production and linguistic awareness, and to gather information on students’ opinions concerning the intervention. The findings suggest that the implementation of the instruments was successful in terms of raising students’ language awareness in oral production and provided us with valuable insights regarding their perceptions of a new sort of assessment as part of their learning process.

Integrating Assessment in a CLIL-Based Approach for Second-Year University Students

Incorporación de la evaluación basada en el aprendizaje integrado de contenidos y lenguas extranjeras para estudiantes universitarios de segundo año

Erika De la Barra*

Sylvia Veloso**

Lorena Maluenda***

Universidad Chileno-Británica de Cultura, Santiago, Chile

*edelabarra@ubritanica.cl

**sveloso@ubritanica.cl

***lmaluenda@ubritanica.cl

This article was received on July 21, 2017 and accepted on March 12, 2018.

How to cite this article (APA, 6th ed.): De la Barra, E., Veloso, S., & Maluenda, L. (2018). Integrating assessment in a CLIL-based approach for second-year university students. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 20(2), 111-126. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v20n2.66515.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This article examines the intervention, through the design and pedagogical implementation of two rubrics based on theory from the Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) approach, to assess the oral competences in English of a group of sophomores in a content subject. The data collection and subsequent analysis included both quantitative and qualitative sources to evaluate students’ oral production and linguistic awareness, and to gather information on students’ opinions concerning the intervention. The findings suggest that the implementation of the instruments was successful in terms of raising students’ language awareness in oral production and provided us with valuable insights regarding their perceptions of a new sort of assessment as part of their learning process.

Key words: Assessment, content and language integrated learning, linguistic awareness, oral production, rubric.

Este artículo examina la intervención, a través del diseño e implementación de dos rúbricas basadas en las teorías surgidas del enfoque del aprendizaje integrado de contenidos y lenguas extranjeras para evaluar competencias orales en inglés de un grupo de estudiantes universitarios de segundo año en un curso de contenido dictado en ese idioma. La recolección de datos contempló fuentes cuantitativas y cualitativas para evaluar su producción oral y conciencia lingüística, y para recabar sus opiniones de la intervención. Los resultados sugieren que la implementación de los instrumentos fue exitosa al mejorar la conciencia lingüística de esos estudiantes en la producción oral y nos proporcionó información valiosa relacionada con sus percepciones sobre nuevos tipos de evaluación como parte de su proceso de aprendizaje.

Palabras clave: aprendizaje integrado de contenidos y lenguas extranjeras, conciencia lingüística, evaluación, producción oral, rúbrica.

Introduction

The need to improve linguistic and communicative skills in English has been a major aim of different governments in Chile. Some important steps have been taken in this direction by the Ministry of Education, such as the creation of the “Inglés Abre Puertas” (PIAP) or English Opens Doors programme in 2004, aimed at improving English levels for students from Grade 5 to 12 through the definition of certain national standards to learn English and a strategy for professional development. However, the results published by the National Accreditation Commission from SIMCE (Sistema de Medición de la Calidad de la Educación) examinations have shown that there is still much work to be done as the majority of students at the secondary level, especially in public and subsidized schools, still do not reach the expected CEFR (Common European Framework of Reference) A2-B1 level on standardized tests, which is required to get a certification.

As a matter of fact, three major SIMCE examinations have been conducted in Chile to measure students’ level of English. The tests have only included the receptive skills and they are correlated with CEFR standards. The first examination took place in 2010, and only 11% of the students were certified. In 2012, 18% of the students got a certification while in 2014, 25% of the students were certified. According to English First (2017), the low level of English performance in Chile echoes a similar reality throughout Latin America. In contrast to Europe and Asia that always perform over the world average, Latin American countries are below the average. The only country in Latin America that possesses a rather high level of English is Argentina; the rest of the countries such as Uruguay, Brazil, Mexico, Peru, Ecuador, Chile, and Colombia have a low level. Moreover, English teachers in the Latin American region generally show a low level of performance with the exception of Costa Rica and Chile, where the majority of the teachers surveyed had a B2 or B2+ level in 2015.

The Chilean Ministry of Education (MINEDUC, 2014), through PIAP and the academic standards for the country, stipulates that students enrolled in English teacher training programmes must reach the CEFR C1 level in order to obtain their teaching degree. Considering the low levels of linguistic competence students develop while in secondary school, this presents a huge challenge to students and teacher trainers. At Universidad Chileno-Británica de Cultura (UCBC), in which the present study took place, students must show a minimum of a CEFR A2 level to be accepted in the translation and English teaching training programme; therefore, there is a major challenge to help students in our English as a foreign language (EFL) context advance from an elementary level of English to a proficient and professional one within the 4½ year degree programmes.

The research outlined in this article was carried out at the UCBC as part of an action research programme sponsored by the university in 2016 (see Burns, Westmacott, & Hidalgo Ferrer, 2016, for a description). The study was conducted with second year students enrolled in both the programmes of English teacher training and translation, and specifically in the course of British Studies I (BS1), which is compulsory for students of both programmes. This course has always been taught in English and its main objective is that students analyse and discuss the most important historical events within the context of British history and culture. Until this study, the summative assessments of the course required students to demonstrate their content knowledge and analytic skills in English, but did not involve any assessment of their linguistic or pragmatic competence. Similarly, teachers of this course noticed that students seemed to be somewhat “relaxed” about their use of English, both in class and in assessments. We believed then that if linguistic competence were included in the assessment, it would improve students’ awareness of language use and, consequently, linguistic competence. This is part of the rationale in content and language integrated learning (CLIL) models, such as the ones provided by Räsänen (1999) and Mohan and Huang (2002), who state that both language and content must be assessed in order to improve the learning process. This is also supported by Maggi (2011) who agrees that both language and content must be assessed, and the assessment instruments should be shared with students beforehand, as this is a better procedure to assess integrated competences (Barbero, 2012).

Based on the belief and the scholarly evidence that students should improve their awareness of the language if they were assessed on their linguistic competence together with the content, we designed two rubrics that included both aspects. With the aim of investigating students’ learning experiences and their perspectives of such an approach, we asked the following questions:

- Does the integration of the assessment of oral linguistic competence in BS1 have an effect on students’ language awareness?

- What are students’ perceptions of the integration of the assessment of oral linguistic competence in the BS1 course with regard to its impact on their oral language production?

Literature Review

As was previously mentioned, the course on British studies is compulsory for second year students. Before this research was carried out, only content was assessed which, we suspected, resulted in a reduced focus on their language use. Based on the theory of CLIL, this research highlights the integration of both language and content, which states that language is learnt more effectively if there is a meaningful context, as in real life people talk about content they find meaningful and not about language itself (Snow, Met, & Genesee, 1989).

In the typical academic context, the linguistic component and content are usually taught independently, and as has been noted (e.g., Dalton-Puffer, 2007), linguistic instruction alone is not usually as successful as hoped. The integration of both would favour motivation and real meaning, which is a condition for a more naturalistic approach to learning a foreign language. The pro-CLIL argument is that the curricula of the so-called content subject (e.g., geography, history, and business studies) “constitutes a reservoir of concepts and topics, and which can become the ‘object of real communication’ where the natural use of the target language is possible” (Dalton-Puffer, 2007, p. 3). As a result, the possibilities of becoming more competent linguistically in English increase if such an approach is taken instead of merely assessing content. In a more CLIL oriented approach, both language and content become protagonists in the student’s learning process.

Language Awareness

Research has shown that the use of CLIL-based approaches in content courses helps students remain interested in the process of learning a language and, for that reason, their language awareness increases. Publications exploring this area reveal that CLIL-based instruction showed improvements in terms of linguistic accuracy (Lamsfuß-Schenk, 2002; Lasagabaster, 2008; Pérez-Vidal & Roquet, 2015; Ruiz de Zarobe, 2008) if contrasted with traditional instruction.

As it is a key concept for our study, we will discuss some of the implications of language awareness. Language awareness is “a person’s sensitivity and conscious awareness of the nature of language and its role in human life” (Van Essen, 2008, p. 3). Pedagogical approaches that aim at increasing language awareness seek to develop in students the capacity to observe the language rules and mechanisms; as a result, students can grow more interested in how language works (Hawkins, 1984). Van Essen (2008) adds that traditionally language awareness has been associated with the ability to know how the target language works at the phonological, semantic, and morphological level. Other studies (Papaja, 2014; Van Lier, 1995) have also established that language awareness may be a positive outcome of CLIL approaches.

Language awareness requires development of different dimensions of language. Svalberg (2009) proposed a framework that includes three main areas, which contribute to the enhancement of language awareness: the cognitive, the affective, and the social domain. The first area is related to the ability to become aware of patterns, contrasts, categories, rules, and systems; thus, language learners need to be alert to and to pay focused attention to those aspects in order to construct or expand their knowledge of the target language. The second aspect, the affective domain, has to do with the development of certain attitudes, such as attention, curiosity, and interest; effective language learners display a positive attitude towards the language, a willingness to improve, and autonomy to overcome difficulties with tasks. Finally, the social domain refers to language learners’ ability to successfully and effectively initiate and maintain an interaction.

These three domains combined may lead to the development of the language learners’ attention, noticing, and understanding of the target language (Lightbown & Spada, 2006). With that goal in mind, the intervention in the present study aimed to provide students with explicit, guided, and personalized feedback on their oral production so that they would become more conscious of all these aspects involved in learning a second language, and also to assist them in focusing attention on their less developed areas.

Oral Language Production

Since this study focuses on language awareness in relation to its impact on oral production in general courses that convey certain content through English, it is relevant to mention some essential features of oral production.

Firstly, oral production is considered a difficult macro skill to master since it involves knowledge that goes beyond the linguistic aspects (Bygate, 2003; Pollard, 2008). In order to articulate a comprehensible utterance, language learners activate not only their morphological, phonological, and syntactic knowledge, but they also need to take into consideration the target listener or audience. This ability, or pragmatic competence (Bachman, 1990), can be a decisive factor at the moment of selecting words and adjusting the message. Considering this, we deemed it pertinent to include pragmatic competence in the assessment of this group of students’ oral production.

It is also important to consider that oral production is affected by time factors. Unlike writing, when speaking we are making choices of words in situ; although a speech can be pre-planned, the responses from the audience cannot be controlled. However, and given the nature of oral production, communicative impasses can be overcome by using strategies such as redundancy, repetition, changing the rate of delivery or intonation, or the use of fillers, among other discourse strategies (Brown, 2001). The present study intended to evaluate the use of these strategies by giving the group of language learners two different assessments of their oral production: a more pre-planned instance—an oral presentation—and a more spontaneous instance—an oral interview—in which they could apply the strategies mentioned by Brown (2001). The pedagogical implications of this were that students improved their communication strategies and their pragmatic competences in the oral production in a course that had been originally planned to develop only critical and research skills.

Integrated Assessment: The Rubric

The main question we wanted to answer was how to make students more aware of their oral language production within a content course. Following a review of work by authors recommending CLIL-based approaches, we concluded that it was through assessment that we could help students become more aware of the language while they learned the content at the same time. In fact, some authors have argued that within a CLIL-based approach it is necessary to assess both language and content (Mohan & Huang, 2002; Räsänen, 1999). Also, Maggi (2011) recommends that “the weight given to the content of the discipline and the language should be determined and shared with the students” (p. 57). Similarly, Barbero (2012) states that: “Assessment is fundamental to the success of CLIL, as in any other field of education, since we know that assessment guides learning and students end up focusing on what they are assessed” (p. 38). Barbero also states that an appropriate tool to evaluate integrated competences in CLIL approaches are assessment rubrics. All the scholarly evidence supports the idea that including the assessment of both content and language in a rubric would help students become more aware of the linguistic competence in content courses, and their language learning would be consequently more effective.

Barbero (2012) defines the rubric as “a tool in the form of a matrix which is used to assess learners’ performance” (p. 49). In a rubric, there are rows listing the characteristics of the performance that will be assessed, and in the columns, the descriptors indicate the qualities of this performance and their scores. The advantages of using a rubric in an integrated system are that it is possible to provide feedback for the students, it represents a guide for students and for teachers, and it also makes assessment easier as it becomes more objective. Barbero states that in CLIL the content and language can be integrated into one rubric where the two are correlated and combined thus providing a complete description of students’ competences. She also argues that for the language part of the rubric the scales of the CEFR can be useful. Taking this into consideration, the rubrics designed for the purposes of this research consider the CEFR scale for the language component of the rubric. This allows students to compare their performance in English in the course of BS1 and in the language course that uses the CEFR scale as well. Students who are doing the BS1 course are doing an English course aligned with B2 level in the CEFR.

The rubric designed for this study is an analytic rubric that integrates both language and content. It contains the criteria or the characteristics of the task to be assessed, and the descriptors that provide the proficiency levels of the performance. There is also a rating score to measure the levels of performance. To design this rubric, it was important to keep in mind the learning goals of both the contents of the course of BS1 and the linguistic goals of the second-year students in terms of language. This is particularly important in CLIL, as Barbero (2012) suggests, as all the content and language elements are involved in evaluation.

The steps we followed in the construction of the rubric considered the process elaborated by Barbero (2012) and Maggi (2011):

- Identify the tasks that are typical of the subject;

- Develop the set of standards consistent with the teaching objectives;

- Identify the criteria and the essential elements of the task;

- Identify competence levels for each criterion;

- Find competence descriptors for each level and criterion;

- Design the scores for the rubric.

It is worth mentioning that the rubric design process described above also led us to consider two relevant aspects in any assessment experience: validity and reliability.

To define validity, we have employed the definitions provided by Cambridge English Language Assessment (2016) since all the rubrics used in the language courses at the university in which this study was carried out use Cambridge rubrics as background models to build their own. According to Cambridge English Language Assessment, validity “is generally defined as the extent to which an assessment can be shown to produce scores and/or outcomes which are an accurate reflection of the test taker’s true level of ability” (p. 20). It is then connected to the inferences drawn from the test as appropriate and meaningful in specific contexts and, therefore, results retrieved from the test end in evidence from which certain interpretations can be made. Luoma (2009), in turn, defines reliability as score consistency. In short, this consistency refers to the degree to which an assessment tool produces stable and consistent results within a context and over time.

Validity in Cambridge examinations considers content and context-related aspects such as profile of test takers, implementation of procedures to ensure that bias in test items is minimised, and the definition of task characteristics and how they are related to the skill being assessed, among others. As for reliability, some of the elements considered to ensure this aspect comprise criterion-related aspects (e.g., developing and validating rating scales, and having a rationale to make sure that test materials are calibrated so that standards are set and maintained), and scoring related aspects, such as investigating statistical performance of items and tasks to determine if they are performing as expected.

The oral interview rubrics designed for the purpose of carrying out this project were inspired to some extent by the Cambridge English B2 speaking assessment scale in terms of some of categories and descriptors included (grammar and vocabulary, discourse management, pronunciation, and interactive communication), and procedures, by having two assessors in the oral presentation and an interlocutor and an assessor in the oral interview (Cambridge English Language Assessment, 2011).

The Context

As mentioned in the introductory part of this paper, this project was carried out with third semester students who were taking BS1. These students belong either to the English teacher training or to the translation studies programmes. These degree programmes have a formal length of nine semesters each. Therefore, by the time the students reach their second year or third semester, they have already been exposed to at least 432 English language teaching hours. Among the participants, 11 students were enrolled in the English teaching training programme (PEI) while the remaining 21 were part of the translation programme (TIE). This represents a total of 32 participants for the purposes of this research.

The principle aim of BS1 is to help students analyse the main historical, political, and economic events that have taken place in Great Britain since early Celtic times to the Wars of the Roses. As described earlier, the course is taught in English but the focus has been mostly on the content and not on the linguistic aspect. Students meet twice a week for three hours of classes and they are assigned certain reading material from the Illustrated History of Britain (McDowall, 2008), and The Oxford History of Britain (Morgan, 2010).

Before this action research project was conducted in the first semester of 2016, in terms of assessment, students were asked to carry out an individual presentation on different topics and they were assessed through a rubric that used seven criteria (introduction of the topic; knowledge of the topic; ability to engage and involve the audience; suitability of presentation for purpose and audience; voice: clarity, pace, and fluency; vocabulary: sentence structure and grammar; and pronunciation) with a maximum score of 70 points. Scores were placed at three levels: “below expected level”, allotted 1-3 points; “at expected level”, given 4-5 points; and “above the level” category allotted 6-7 points. The emphasis of the assessment was on content and only 20% of the rubric was devoted to assessing the linguistic aspect. The correct use of the target language played a minor role in the former rubric; therefore, it did not include detailed band descriptors to guide the assessor or to help students focus on specific areas. Thus, most of the students turned to their mother tongue whenever they felt unable to express themselves in English and that barely affected their final mark. For this reason, we wanted to explore whether a formal stage of preparation on two assessment instruments could improve the students’ oral performance, and determine if raising awareness of the rubrics and the linguistic elements to be tested had an impact on the oral production of this group of students in this content subject.

Procedures

This action research study followed a mixed methods design. The data collection and the subsequent analysis included both quantitative and qualitative sources; the former were gathered through the use of performance instruments, that is, the two rubrics, whereas the latter considered text information collected through a questionnaire. Thus, the data collection process comprised three instruments: two rubrics to assess oral performance and one questionnaire. This approach allowed for the integration of several sources of data in order to have a better understanding of the issue (Creswell, 2003).

The first rubric (see Appendix A) was used during the first two months of the semester to assess individual presentations; in this activity, each student was required to prepare a 15-minute presentation on a topic related to the contents of the BS1 course. Since it was the first time they had been assessed using this rubric, they were gradually introduced to the instrument before the round of presentations started. First, they were shown the rubric, then, every category was analysed with the students and explained in detail; afterwards, they had the opportunity to try out some criteria of the rubric in short activities done in classes, and finally they used the complete instrument to assess a 15-minute presentation carried out by one of the researchers. This process took place over approximately six classes, which represented about three weeks, and aimed at both familiarizing students with the instrument, and guiding their awareness of what they were expected to display in each presentation. During each of the students’ presentations, two researchers were present using the rubric independently, so that results could be compared and a more objective assessment of the performance could be obtained. During the following class, students received oral feedback and a marked copy of the rubric.

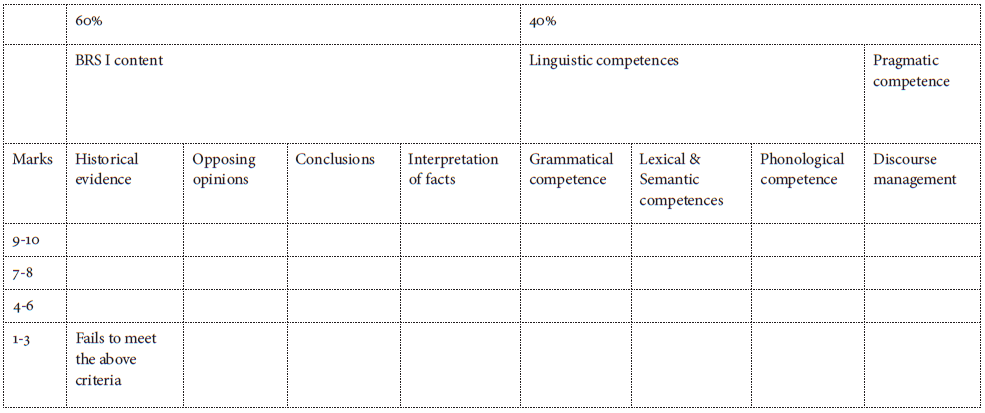

This first instrument encompassed four categories: Presentation strategies (20 points), British Studies content (40 points), Linguistic competence (30 points), and Pragmatic competences (10 points), so the maximum score for this rubric is 100 points. The categories are explained below:

- Presentation strategies: This category aims at assessing the skills each presenter displayed when carrying out their oral presentation. It is subdivided into two subcategories: audience and eye contact. The former refers to the capacity to adapt the presentation according to the audience; it also refers to the ability to include facts or information about the topics that might keep the audience interested. The latter refers to the capacity to monitor the audience efficiently as a whole and make changes or variations accordingly.

- British Studies content: This category assesses the command of the content presented by the student. It is subdivided into four subcategories: historical evidence, opposing opinions, conclusions, and historical facts. Historical evidence refers to students’ capacity to select accurate information for the presentation; the second subcategory assesses the ability to analyse historical information from different points of view. The third one assesses students’ reflections and the ability to draw general conclusions based on the topics presented. Finally, historical facts category assesses further interpretation or arguments on historical facts.

- Linguistic competence: This category comprises three aspects: grammatical competence, lexical and semantic competences, and phonological competences. The first one assesses the students’ control of simple and some complex grammatical forms; the second one assesses students’ use of vocabulary and accurate word choice; and the third one assesses the appropriate articulation of individual sounds.

- Pragmatic competence: This area is made up of one subcategory called discourse management, which refers to the students’ ability to combine ideas using linking words.

The questionnaire was applied after the round of presentations was over; students were asked to complete an online survey in order to gather their perceptions of the rubric. It aimed to reveal whether the rubric had been useful for them in preparing their presentations and if it had helped them identify weaknesses concerning linguistic and pragmatic aspects. This semi-structured instrument consisted of 18 questions divided into three sections: content, organization, and usefulness of the rubric. Each of the sections contained up to seven closed questions with a Likert scale and one open question which aimed at gathering suggestions to improve the rubric in future assessment.

The second rubric (see Appendix B) was used to assess an oral interview at the end of the semester. In this activity, students had to answer questions about the contents of the course (BS1). The task required students to talk both individually and in pairs about selected topics. The examination format resembles a Cambridge First Certificate of English (FCE) oral interview, including a warmer, individual questions, and pair interaction; this interview lasted about 12 minutes each pair. This format was chosen for two reasons: first, third year students use textbooks and materials in the UCBC language courses that prepare them to take the FCE examination and their level of English is expected to be B1+; second, the students are already familiar with the format of this type of examination. Since the second rubric was very similar to the first rubric, only one class was devoted to explaining the rubric and its requirements before the examination period started. During the oral interviews two researchers were present and used the instrument to assess individual performance. The week after the examination period, students received individual feedback and a copy of the rubric containing the final mark.

As previously stated, the rubric constructed for the assessment of this task was similar to the rubric designed to assess the oral presentations. They have in common three of the categories: British Studies content, Linguistic competences, and Pragmatic competences; thus, the similarities of the rubrics allow for comparison and contrast of the results. The only category that was not considered here was the presentation strategies because of the nature of the second task. The total score of this rubric is 80 points.

The process of data analysis comprised a detailed examination of the results obtained by the students in each of the components of both rubrics and took into account their opinions stated in the questionnaire. Thus, in order to analyse the quantitative data we added up the scores obtained by each student in both rubrics although considering the content and the linguistic part separately; after that, results were compared according to the different categories and the descriptions. The qualitative part, on the other hand, was provided by the identification of recurrent themes which appeared basically in the answers from the questionnaire; these answers allowed us to classify students’ opinions in regard to the intervention.

Findings

This research process led us to the findings discussed separately in the following section.

Language Awareness

As previously stated, the intervention process began before the assessment period; therefore, it could be expected that since students knew beforehand what was going to be assessed, their grades would be above the passing mark; the results achieved in both assessments: the oral presentation (OP) and the oral interview (OI) in BS1 confirmed such. On a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being the maximum score, the overall results show that in terms of grammatical competence, the average was 7.6 in the OP while it reached 7.4 in the OI; regarding lexical and semantic competence the average of OP was 8.5 while the OI was 7.9. The average in the phonological area was 7 in the OP and 7.6 in the OI, and in terms of the pragmatic aspect, both assessments showed an average of 7.5.

Figure 1 provides a summary of the results in each of the assessed areas.

Figure 1. Comparison of Oral Presentation and Oral Interview Results

As Figure 1 shows, the average of all the scores of the participants in the study is high. This finding suggests that students performed well in both assessments, which we believe can be explained by the use of the rubric and its linguistic aspects making them more attentive to the language they used. This attentiveness to patterns, contrasts, categories, rules, and systems of the language is what Svalberg (2009) refers to as a cognitive domain of language awareness.

The Oral Presentation

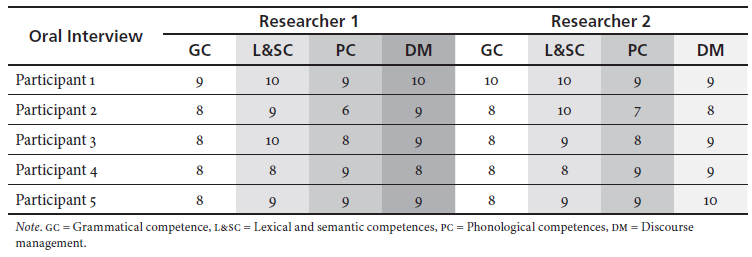

Table 1 is included as a way of illustrating the results obtained. This shows the scores given independently by the two researchers who were present at the students’ presentations. This sample considers the scores of five randomly chosen participants. This comparison helped to validate the rubric, since the scores assigned by each researcher are quite similar.

Table 1. Sample Scores in Oral Presentation

In the case of Participants 1 and 2, who scored the highest, their main errors were in the phonological aspect such as the production of some phonemes like /f/ or /s/; and the pronunciation of /t/ at the end of the regular verbs. There seem to have been fewer problems in terms of grammatical competence or lexical and semantic competence, which means that at least in the case of these students they appear to have reached a high degree of awareness of how language works in terms of grammar and lexis. However, in the case of Participants 3 and 5, the major problems were in grammatical competence because they still produced sentences with several elementary grammar or structural mistakes such as omission of -ed endings in the regular past tenses and extreme hesitation which made their speech difficult to follow.

The feedback on the students’ performance was carefully provided one week later by the researchers in an interview that took at least 15 minutes per participant. Along with acknowledging their achievements, they were also informed in detail about the linguistic problems that had appeared during the oral presentations. They were also given some suggestions for improvement; some of these activities involved writing sentences to use problematic words, or reinforcing structural areas through grammar activities, or recording another presentation so that students could listen to themselves and monitor their errors. In the questionnaire used later, 94% of the participants agreed that the feedback provided by the researchers had been very appropriate and useful and had helped them become more aware of the linguistic elements in the BS1 course.

The Oral Interview

The oral interview was assessed at the end of the semester and Table 2 illustrates a sample of the scores given by two of the researchers independently to the same five participants.

Table 2. Sample Scores in Oral Interview

As with the oral presentation rubric, the scores provided by the researchers were quite similar, having differences of no more than 1 point. These results were slightly higher than those from the oral presentation, suggesting that students might have become more aware of the linguistic aspect because they were more careful with their grammar and vocabulary in this second assessment. They chose their words and expressions more carefully and tried to be more fluent and less hesitant.

Only Participant 4 had problems with the -ed endings as she did not use them to refer to past events; the majority of the mistakes for all five students occurred at the phonological level with the mispronunciation of phonemes; misplaced stress in words like catholic, mythological, understand, important, and in terms of discourse management the main problems were the use of connectors that either were too simple (e.g., but, and, or instead of however, moreover, either...or) or were absent. However, all the participants were less hesitant and showed more confidence.

As with the oral presentation, individual feedback was provided by the researchers so that students could become more aware of the linguistic aspects.

Questionnaire

This instrument gathered information on the students’ opinions about the use of the first rubric. It consisted of rating scale statements aimed at determining their perception towards the content, organization, and usefulness of this instrument, as well as open questions for students to make suggestions about other aspects that they would include in future oral assessments.

Concerning the content of the rubric the majority of the students claimed that they perceived this instrument to be very appropriate (61%) or appropriate (36%), with only one student out of 32 considering the content of the rubric to be inappropriate (3%). Three students suggested that the rubric for the oral presentations should also evaluate the quality and appropriacy of the audio-visual materials used.

Regarding the organization, again most of the students considered the instruments very appropriate (54%) and appropriate (45%), whereas 6% of the sample described the layout as inappropriate. When asked if they would change the organization of the rubric 87.5% answered No, with only four students (12.5%) suggesting change.

Finally, concerning the usefulness of these two instruments, when students were asked whether the rubrics helped them to increase their awareness of the language used in oral assessments 78% agreed, 19% partially agreed, and one (3%) disagreed. When asked whether the rubrics helped them identify weaknesses and strengths in the target language most of them agreed and partially agreed (76% and 21% respectively) and 3%, or one student, disagreed. The last question aimed to determine if students thought that other courses from their programs should include assessment of the target language in oral presentations; 87.5% of the interviewees agreed, whereas 12.5% thought that the use of English should not be assessed in oral presentations.

Discussion

As mentioned earlier, the purpose of this study was both to determine the effect of integrated assessment on students’ language awareness and explore students’ perceptions concerning this matter.

The findings showed that students appeared to become more aware of the language aspects, including linguistic and pragmatic competence in the BS1 course. This finding is supported by the responses in the students’ questionnaire. Most of them perceived the use of the rubrics and the feedback provided by the researchers as useful tools to evaluate both the content and linguistic aspects in oral tasks, giving them insights into the areas on which they should centre their attention to improve their performance in English.

It is also worth mentioning, however, that the rubric used to assess the oral presentations needs to be revised in order to determine the incorporation of other elements such as quality and pertinence of the audio-visual materials, as suggested by the subjects of the study, or the dependency on notes. We observed that some students relied substantially on their notes while presenting; this issue can undoubtedly affect a valid assessment of the oral performance, since they are not producing language by themselves, but rather reading out loud prepared notes which are unlikely to reflect their actual performance.

Although this study considered integrated assessment and language awareness in only one course, BS1, we strongly believe that if other courses, which are also taught in English, could incorporate linguistic aspects in their assessments, the associated language skills of the students could be improved. It would require collaborative work among all the teachers in order to first, design suitable rubrics for each course, and second, determine a set of actions to familiarize students with the instruments before the assessments.

The possibility to carry out this research gave us the chance to reflect on our teaching practice as students made some valuable suggestions. One of the most interesting is recording students’ performance which they perceive as a key element to become more confident in the language. Apart from this, it has given us the chance to reflect on the assessment process that has been carried out at the university so far. We have realized it does not always include students to the point of making them active participants of their own evaluation. In fact, the number of students who still perceive evaluation and assessment as punishment instead of a proper opportunity to learn is not small. Changing the minds of both teachers and students regarding assessment is an interesting insight that has come out of this project.

Finally, it is also worth mentioning that this may have implications as regards the way students are learning English at schools in Chile. Except for the bilingual schools, most of the public and subsidised schools have only a linguistic approach to the teaching of English and not a content approach. We strongly believe in the CLIL rationale that teaching English within a context can improve the linguistic awareness of the students. This could make a difference in the poor levels of performance that Chile has experienced on the standardized tests. A policy in this aspect should consider both the introduction of content taught in English at schools, and reconsider how assessment is being carried out to involve students more thoroughly in their learning process.

Conclusions

According to the analysis of the results and considering the research process, a number of conclusions can be drawn. First, it appears that integrated assessment benefited both the oral linguistic competence and awareness of the students. Since it was the first time students were assessed using these instruments, the intervention period was of paramount importance. Introducing them to the rubrics as well as giving them the opportunity to try them out themselves in different activities led the students to a better understanding of the requirements of the tasks and provided them with valuable insights into their weaknesses and strengths when it comes to oral performance. The task results suggest that the intervention not only empowered students to take responsibility for their own learning, but also helped them to self-direct their efforts in order to achieve the desired competences.

Secondly, in the questionnaire students expressed their appreciation of the specific feedback provided after both assessments and the explicit introduction to the rubric; most of them asserted that these two aspects helped them become more aware of the linguistic part of the course. They valued the fact that they received written feedback giving accounts of their potential areas for improvement in a course that was not specifically intended to be a language course. This had never been done before because all the feedback students used to receive was in terms of their content knowledge and not about the language.

Finally, we believe that raising awareness of the language in content courses reinforces the rationale behind the CLIL approach which states that students will learn a foreign language if it is presented and practised in meaningful contexts rather than just linguistic settings. If the target language is considered as part of the assessments in content courses such as BS1, students are likely to pay more attention to it. Our study validates the research conducted by Barbero (2012) as part of the three-year AECLIL project in Europe in terms of the relevance of rubrics to assess both content and language, as this is a key element in all the approaches based on CLIL rationale. For the university and for the teachers it has meant a revision of policies in terms of assessment of content courses taught in English which has facilitated making decisions. It also validates the experience described by Carloni (2013) with the CLIL learning centre at the University of Urbino, and Pérez-Vidal (2015) as part of her experience of CLIL or ILCHE as this approach is preferably called in higher education, as an instrumental role to promote bilingualism, mobility, and internationalisation.

References

Bachman, L. F. (1990). Fundamental considerations in language testing. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Barbero, T. (2012). Assessment tools and practices in CLIL. In F. Quartapelle (Ed.), Assessment and evaluation in CLIL (pp. 38-56). Pavia, IT: Ibis. Retrieved from http://aeclil.altervista.org/Sito/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/AECLIL-Assessment-and-evaluation-in-CLIL.pdf.

Brown, H. D. (2001). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy. White Plains, US: Longman.

Burns, A., Westmacott, A., & Hidalgo Ferrer, A. (2016). Initiating an action research programme for university EFL teachers: Early experiences and responses. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research, 4(3), 55-73. Retrieved from http://www.urmia.ac.ir/sites/www.urmia.ac.ir/files/4%20%28ARTICLE%29.pdf.

Bygate, M. (2003). Language teaching, a scheme for teaching education: Speaking (10th ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Cambridge English Language Assessment. (2011). Assessing speaking performance: Level B2. Retrieved from http://www.cambridgeenglish.org/images/168619-assessing-speaking-performance-at-level-b2.pdf.

Cambridge English Language Assessment. (2016). Principles of good practice: Research and innovation in language learning and assessment. Retrieved from http://www.cambridgeenglish.org/images/22695-principles-of-good-practice.pdf.

Carloni, G. (2013). Content and language integrated learning in higher education: A technology-enhanced model. In J. E. Aitken (Ed.), Cases on communication technology for second language acquisition and cultural learning (pp. 484-508). Hershey, US: IGI Global.

Creswell, J. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, US: Sage Publications.

Dalton-Puffer, C. (2007). Discourse in content and language integrated (CLIL) classrooms. Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/lllt.20.

Education First. (2017). EF English Proficiency Index. Retrieved from https://www.ef.com/__/~/media/centralefcom/epi/downloads/full-reports/v7/ef-epi-2017-spanish-latam.pdf.

Hawkins, E. (1984). Awareness of language: An introduction. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lamsfuß-Schenk, S. (2002). Geschichte und sprache: Ist der bilinguale geschichtsunterricht der königsweg zum geschichtsbewusstsein? In S. Breidbach, G. Bach, & D. Wolff (Eds.). Bilingualer sachfachunterricht: Didaktik, lehrer-/lernerforschung und bildungspolitik zwischen theorie und empirie (pp. 191-206). Frankfurt, DE: Peter Lang.

Lasagabaster, D. (2008). Foreign language competence in content and language integrated courses. The Open Applied Linguistics Journal, 1, 31-42. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874913500801010030.

Lightbown, P., & Spada. N. (2006). How languages are learned. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Luoma, S. (2009). Assessing speaking (5th ed.), Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Maggi, F. (2011). Assessment and evaluation in CLIL. Paper presented at the 4th International Conference ICT for Language Learning. Retrieved from https://www.unifg.it/sites/default/files/allegatiparagrafo/21-01-2014/maggi_assessment_and_evaluation_in_clil.pdf.

McDowall, D. (2008). An illustrated history of Britain. Harlow, UK: Longman.

MINEDUC. (2014). Estándares orientadores para la Carrera de pedagogía en inglés. Santiago, CL: CPEIP. Retrieved from http://portales.mineduc.cl/usuarios/cpeip/File/nuevos%20estandares/ingles.pdf.

Mohan, B., & Huang, J. (2002). Assessing the integration of language and content in a Mandarin as a foreign language classroom. Linguistics and Education, 13(3), 405-433. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0898-5898(01)00076-6.

Morgan, K. O. (Ed.). (2010). The Oxford history of Britain. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Papaja, K. (2014). Focus on CLIL: A qualitative evaluation of content and language integrated learning (CLIL) in Polish secondary education. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars.

Pérez-Vidal, C. (2015). Languages for all in education: CLIL and ICLHE at the crossroads of multilingualism, mobility and internationalisation. In M. Juan-Garau & J. Salazar-Noguera (Eds.), Content-based language learning in multilingual education environments (pp. 31-50). Berlin, DE: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-11496-5_3.

Pérez-Vidal, C. & Roquet, H. (2015). CLIL in context: Profiling language abilities. In M. Juan-Garau & J. Salazar-Noguera (Eds.), Content-based language learning in multilingual education environments (pp. 237-255). Berlin, DE: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-11496-5_14.

Pollard, L. (2008). Lucy Pollard’s guide to teaching English [e-book]. Retrieved from http://lingvist.info/english/lucy_pollards_guide_to_teaching_english/.

Räsänen, A. (1999). Teaching and learning through a foreign language in tertiary settings. in S. Tella, A. Räsänen, & A. Vähäpass (Eds.), From tool to empowering mediator: An evaluation of 15 Finnish polytechnic and university level programmes, with a special view to language and communication (pp. 26-31). Helsinki, FI: Edita.

Ruiz de Zarobe, Y. (2008). CLIL and foreign language learning: A longitudinal study in the Basque Country. International CLIL Research Journal, 1(1), 60-73. Retrieved from http://www.icrj.eu/11/article5.html.

Snow, A. M., Met, M., & Genesee, F. (1989). A conceptual framework for the integration of language and content in second/foreign language instruction. TESOL Quarterly, 23(2), 201-217. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587333.

Svalberg, A. M.-L. (2009). Engagement with language: Developing a construct. Language Awareness, 18(3), 242-258. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658410903197264.

Van Essen, A. (2008). Language awareness and knowledge about language: A historical overview. In J. Cenoz & N. H. Hornberger (Eds.), Encyclopaedia of language and education (2nd ed., Vol. 6, pp. 3-14). New York, US: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-30424-3_135.

Van Lier, L. (1995). Introducing language awareness. London, UK. Penguin Books.

About the Authors

Erika De la Barra has been an English teacher since 1997. She is currently a full time professor at Universidad Chileno-Británica de Cultura where she teaches English, British culture, and literature. She holds a PhD in literature from Universidad de Chile.

Sylvia Veloso has been an EFL teacher since 2012. She has experience in teaching children, teenagers, and adults. She is currently the teaching practice coordinator of the TEFL programme at Universidad Chileno-Británica de Cultura. She has a B.A. in English language teaching and an M.A. in applied linguistics and ELT from Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

Lorena Maluenda has been an EFL teacher since 2000. With experience teaching both teenagers and adults, she is currently course director of the TEFL programme at Universidad Chileno-Británica de Cultura. She holds a B.A. in English language teaching and an M.A. in linguistics from Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

Appendix A: Oral Presentation Rubric

British Studies I

Pedagogía en inglés / Traducción inglés-español

Evaluation Criteria: Oral presentation

Student’s name:

Observer:

Appendix B: Interview Rubric

British Studies I

Pedagogía en inglés / Traducción inglés-español

Evaluation Criteria: Interview

Student’s name:

Observer:

References

Bachman, L. F. (1990). Fundamental considerations in language testing. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Barbero, T. (2012). Assessment tools and practices in CLIL. In F. Quartapelle (Ed.), Assessment and evaluation in CLIL (pp. 38-56). Pavia, IT: Ibis. Retrieved from http://aeclil.altervista.org/Sito/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/AECLIL-Assessment-and-evaluation-in-CLIL.pdf.

Brown, H. D. (2001). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy. White Plains, US: Longman.

Burns, A., Westmacott, A., & Hidalgo Ferrer, A. (2016). Initiating an action research programme for university EFL teachers: Early experiences and responses. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research, 4(3), 55-73. Retrieved from http://www.urmia.ac.ir/sites/www.urmia.ac.ir/files/4%20%28ARTICLE%29.pdf.

Bygate, M. (2003). Language teaching, a scheme for teaching education: Speaking (10th ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Cambridge English Language Assessment. (2011). Assessing speaking performance: Level B2. Retrieved from http://www.cambridgeenglish.org/images/168619-assessing-speaking-performance-at-level-b2.pdf.

Cambridge English Language Assessment. (2016). Principles of good practice: Research and innovation in language learning and assessment. Retrieved from http://www.cambridgeenglish.org/images/22695-principles-of-good-practice.pdf.

Carloni, G. (2013). Content and language integrated learning in higher education: A technology-enhanced model. In J. E. Aitken (Ed.), Cases on communication technology for second language acquisition and cultural learning (pp. 484-508). Hershey, US: IGI Global.

Creswell, J. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, US: Sage Publications.

Dalton-Puffer, C. (2007). Discourse in content and language integrated (CLIL) classrooms. Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/lllt.20.

Education First. (2017). EF English Proficiency Index. Retrieved from https://www.ef.com/__/~/media/centralefcom/epi/downloads/full-reports/v7/ef-epi-2017-spanish-latam.pdf.

Hawkins, E. (1984). Awareness of language: An introduction. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lamsfuß-Schenk, S. (2002). Geschichte und sprache: Ist der bilinguale geschichtsunterricht der königsweg zum geschichtsbewusstsein? In S. Breidbach, G. Bach, & D. Wolff (Eds.). Bilingualer sachfachunterricht: Didaktik, lehrer-/lernerforschung und bildungspolitik zwischen theorie und empirie (pp. 191-206). Frankfurt, DE: Peter Lang.

Lasagabaster, D. (2008). Foreign language competence in content and language integrated courses. The Open Applied Linguistics Journal, 1, 31-42. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874913500801010030.

Lightbown, P., & Spada. N. (2006). How languages are learned. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Luoma, S. (2009). Assessing speaking (5th ed.), Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Maggi, F. (2011). Assessment and evaluation in CLIL. Paper presented at the 4th International Conference ICT for Language Learning. Retrieved from https://www.unifg.it/sites/default/files/allegatiparagrafo/21-01-2014/maggi_assessment_and_evaluation_in_clil.pdf.

McDowall, D. (2008). An illustrated history of Britain. Harlow, UK: Longman.

MINEDUC. (2014). Estándares orientadores para la Carrera de pedagogía en inglés. Santiago, CL: CPEIP. Retrieved from http://portales.mineduc.cl/usuarios/cpeip/File/nuevos%20estandares/ingles.pdf.

Mohan, B., & Huang, J. (2002). Assessing the integration of language and content in a Mandarin as a foreign language classroom. Linguistics and Education, 13(3), 405-433. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0898-5898(01)00076-6.

Morgan, K. O. (Ed.). (2010). The Oxford history of Britain. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Papaja, K. (2014). Focus on CLIL: A qualitative evaluation of content and language integrated learning (CLIL) in Polish secondary education. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars.

Pérez-Vidal, C. (2015). Languages for all in education: CLIL and ICLHE at the crossroads of multilingualism, mobility and internationalisation. In M. Juan-Garau & J. Salazar-Noguera (Eds.), Content-based language learning in multilingual education environments (pp. 31-50). Berlin, DE: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-11496-5_3.

Pérez-Vidal, C. & Roquet, H. (2015). CLIL in context: Profiling language abilities. In M. Juan-Garau & J. Salazar-Noguera (Eds.), Content-based language learning in multilingual education environments (pp. 237-255). Berlin, DE: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-11496-5_14.

Pollard, L. (2008). Lucy Pollard’s guide to teaching English [e-book]. Retrieved from http://lingvist.info/english/lucy_pollards_guide_to_teaching_english/.

Räsänen, A. (1999). Teaching and learning through a foreign language in tertiary settings. in S. Tella, A. Räsänen, & A. Vähäpass (Eds.), From tool to empowering mediator: An evaluation of 15 Finnish polytechnic and university level programmes, with a special view to language and communication (pp. 26-31). Helsinki, FI: Edita.

Ruiz de Zarobe, Y. (2008). CLIL and foreign language learning: A longitudinal study in the Basque Country. International CLIL Research Journal, 1(1), 60-73. Retrieved from http://www.icrj.eu/11/article5.html.

Snow, A. M., Met, M., & Genesee, F. (1989). A conceptual framework for the integration of language and content in second/foreign language instruction. TESOL Quarterly, 23(2), 201-217. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587333.

Svalberg, A. M.-L. (2009). Engagement with language: Developing a construct. Language Awareness, 18(3), 242-258. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658410903197264.

Van Essen, A. (2008). Language awareness and knowledge about language: A historical overview. In J. Cenoz & N. H. Hornberger (Eds.), Encyclopaedia of language and education (2nd ed., Vol. 6, pp. 3-14). New York, US: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-30424-3_135.

Van Lier, L. (1995). Introducing language awareness. London, UK. Penguin Books.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Artyom Zubkov. (2022). International Scientific Siberian Transport Forum TransSiberia - 2021. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems. 402, p.1002. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96380-4_109.

2. Tzyy Yuh Maa, Chih Chien Yang, Tsui Ying Lin. (2023). Constructing CLIL reading examination developing principles and items via 4Cs framework and CEFR. APPLIED PHYSICS OF CONDENSED MATTER (APCOM 2022). APPLIED PHYSICS OF CONDENSED MATTER (APCOM 2022). 2778, p.020006. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0114291.

3. Paola Cossu, Gabriela Brun, Darío Luis Banegas. (2021). International Perspectives on Diversity in ELT. , p.173. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74981-1_10.

4. Darío Luis Banegas. (2022). Research into practice: CLIL in South America. Language Teaching, 55(3), p.379. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444820000622.

5. Hao Hao, Masanori Yamada. (2021). Review of Research on Content and Language Integrated Learning Classes from the Perspective of the First Principles of Instruction. Information and Technology in Education and Learning, 1(1), p.Rvw-p001. https://doi.org/10.12937/itel.1.1.Rvw.p001.

6. Jieting Jerry Xin, Yuen Yi Lo. (2025). What constitutes CLIL teacher assessment literacy? Insights from CLIL researchers and teachers. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, , p.1. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2025.2507900.

7. Weijun Liang, Yanjun Wu. (2024). A scoping review of the literature on content and language integrated learning assessment. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education, 12(1), p.101. https://doi.org/10.1075/jicb.21025.lia.

8. Malba Barahona, Jing Hao. (2024). Content and Language Integrated Learning in South America. Multilingual Education. 46, p.147. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-52986-3_9.

9. Cristina Ramírez-Aroca, Arash Javadinejad. (2026). AI-Enhanced CLIL for Embodied Learning: Applying the CLPS Framework in Secondary Physical Education. Education Sciences, 16(1), p.62. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010062.

10. O. G. Byrdina, E. A. Yurinova, S. G. Dolzhenko. (2020). Developing foreign language professional-communicative competence of pedagogical university students by means of CLIL. The Education and science journal, 22(7), p.77. https://doi.org/10.17853/1994-5639-2020-7-77-100.

11. Jiajia Eve Liu, Yuen Yi Lo, Jieting Jerry Xin. (2023). CLIL teacher assessment literacy: A scoping review. Teaching and Teacher Education, 129, p.104150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2023.104150.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

Copyright (c) 2018 PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.