Creating a Teacher Development Program Linked to Curriculum Renewal

Creación de un programa de desarrollo profesoral para una renovación curricular

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v20n2.67937Keywords:

Curriculum renewal, English as a foreign language, professional development, teacher development (en)desarrollo profesional, desarrollo profesoral, inglés como lengua extranjera, renovación curricular (es)

This paper presents one Colombian university English as a foreign language program’s in-house teacher development program for curriculum renewal. This program is an innovative attempt to prepare teachers for implementing a new curriculum and, simultaneously, engages them in professional development activities. The program is a response to the lack of existing teacher and professional development models that fit certain specific contextual needs, including preparation for implementing new curriculum as well as emphases in the updating of particular teaching practices. In addition to presenting the program, the article also describes the integration of key aspects of various existing models of teacher and professional development into one program that meets contextual needs while encouraging positive change among faculty and students.

Creating a Teacher Development Program Linked to Curriculum Renewal

Creación de un programa de desarrollo profesoral para una renovación curricular

Erica Ferrer Ariza*

Paige M. Poole**

Universidad del Norte, Barranquilla, Colombia

*eferrer@uninorte.edu.co

**ppoole@uninorte.edu.co

This article was received on September 25, 2017 and accepted on March 12, 2018.

How to cite this article (APA, 6th ed.):

Ferrer Ariza, E., & Poole, P. M. (2018). Creating a teacher development program linked to curriculum renewal. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 20(2), 249-266. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v20n2.67937.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This paper presents one Colombian university English as a foreign language program’s in-house teacher development program for curriculum renewal. This program is an innovative attempt to prepare teachers for implementing a new curriculum and, simultaneously, engages them in professional development activities. The program is a response to the lack of existing teacher and professional development models that fit certain specific contextual needs, including preparation for implementing new curriculum as well as emphases in the updating of particular teaching practices. In addition to presenting the program, the article also describes the integration of key aspects of various existing models of teacher and professional development into one program that meets contextual needs while encouraging positive change among faculty and students.

Key words: Curriculum renewal, English as a foreign language, professional development, teacher development.

Este artículo presenta un programa de desarrollo profesoral de una universidad colombiana para acompañar una renovación curricular. Este modelo se presenta como una iniciativa innovadora para preparar profesores en implementar un nuevo currículo y, simultáneamente, involucrarlos en actividades de desarrollo profesional. El modelo se da en respuesta a la carencia de modelos existentes de desarrollo profesoral que respondan a las necesidades particulares de un contexto, que incluyan preparación para la implementación de un nuevo currículo, así como un énfasis en la actualización de las prácticas de enseñanza. Adicionalmente, el artículo describe la integración de aspectos clave de modelos existentes en un solo modelo que responda a las necesidades contextuales y al mismo tiempo promueva cambios positivos en los docentes, estudiantes y programas.

Palabras clave: desarrollo profesional, desarrollo profesoral, inglés como lengua extranjera, renovación curricular.

Introduction

Teachers engage in development for various reasons (Bailey, Curtis, & Nunan, 2001). Sometimes it happens as a consequence of teachers’ intrinsic motivation to improve the quality of their teaching practices, gain respect and recognition, become a more effective educator, or to increase individual satisfaction in pursuit of a successful teaching career. In other cases, it comes about as a consequence of extrinsic motivation from a teacher brought on by factors such as maintaining a job or position, obtaining a better salary, accessing higher quality jobs in the field, or getting a promotion. Heystek and Terhoven (2015) explain that both types of motivation can be important for sustainable and participative teacher development, especially connected to curriculum. In the same way, teacher development can be motivated by institutional needs such as increased teacher awareness, updating of teacher knowledge, and adoption of new teaching practices, among many others. In this way, the institution can play a key role in transforming teacher development into a “process of ‘we are developing’ rather than a process of ‘you must develop’ because you are underperforming” (Heystek & Terhoven, 2015, p. 629). In this paper, we reflect on the process of building and implementing a teacher development program (TDP) linked to curriculum renewal in a university English as a foreign language (EFL) program on the Caribbean coast of Colombia. In detailing the process, we explain how university and program faculty were involved in reflecting, analyzing, and making informed decisions about their teaching practices within the framework in order to better design and implement the new curriculum.

Contextual Background

The specific context in which this TPD was designed is that of an eight-level, undergraduate EFL program that serves around 12,000 students annually and relies on approximately 60 teachers, most of whom are Colombian. Students in the program belong to a variety of majors ranging from graphic design or engineering to psychology or social communication. Throughout the program, teachers are expected to help students develop a B2 level of language proficiency according to the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) (Council of Europe, 2001).

Based on systematic classroom observations at all levels of the program, we found students were not developing their language proficiency at the expected level. Careful analysis of students’ grades and exit exam results corroborated these observations and showed that more than 50% of the students were not achieving a B2 level. In order to address this situation, the language institute initiated a curriculum development project (CDP) based on backwards design, using desired learning outcomes to guide the construction of a new curriculum (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). The CDP aimed to identify needs in the program as well as propose a new curriculum that would take into account aspects such as: course goals and outcomes, course materials, student performance, teacher performance, and assessment in a more comprehensive and structured way than before. After a needs analysis was carried out, a preliminary design created, and new course materials chosen, a major challenge arose: working with teachers to reflect on, evaluate, and implement the new curriculum in the classroom.

To respond to this challenge, a TPD was designed to prepare teachers for and involve them in curriculum implementation through taking into account their perceptions and making corresponding adjustments.

Creating a Program for Teacher Development

When creating a teacher development program, several aspects must be clear, including the objectives it aims to achieve in terms of institutional and professional needs. In regard to the TPD in question, the time frame desired for its execution was also important, bearing in mind that the curriculum implementation had fixed dates.

Institutional Needs

In the EFL program in question, there were several institutional needs that motivated the CDP and the TPD. These needs included: fewer and more succinct objectives in course syllabi, a clear progression of student learning outcomes (SLOs), increased awareness among teachers of the content of each level, as well as a need to standardize assessment practices.

Professional Needs

The TPD also took into account varied professional needs of the teachers within the EFL program who would be implementing the new curriculum, the most important of which were: teaching practice update, especially regarding skills instructions, sharing of good classroom practices with their colleagues, and reflection as a professional tool.

General Program Objectives

In an attempt to address all of the abovementioned needs, the following general objectives were formulated for the TPD:

- To involve teachers in the process of evaluating designed curriculum and making suggestions for improvements.

- To improve teacher receptiveness and openness to curricular ideas pre, during, and post-curriculum implementation.

- To provide teachers with spaces to learn about and practice using tools for implementing the new curriculum effectively.

- To facilitate spaces for voicing and addressing teachers’ concerns.

- To facilitate spaces for reflecting on curriculum implementation.

- To promote problem-solving and critical thinking teamwork among teachers.

It is important to clarify that while the program had clear general objectives, it was not a fixed program from the start. As new needs arose or established needs changed during curriculum implementation, the planned activities were evaluated and adjusted to assure they continued meeting the needs identified.

Teacher Development

It is important to note that there is a distinction between teacher training and teacher development. Richards and Farrell (2005) define teacher training as involving “activities directly focused on a teacher’s present responsibilities and . . . aimed at short-term immediate goals” (p. 3) in order to prepare the teacher to accept new responsibilities or positions in their unique context. Teacher development, on the other hand, tends to focus on “general growth not focused on a specific job [and] serves a longer-term goal” (p. 4) that involves a teacher reflecting on their teaching practice. Both concepts are critical for understanding a teacher’s continued growth in and outside the classroom.

More specifically, teacher development is regarded as “the process whereby teachers’ professionalism and/or professionality may be considered to be enhanced” (Evans, 2002, p. 131). Evans (2002) identifies two key elements of teacher development: attitudinal development and functional development. Whereas the former is concerned with the process through which teachers modify their attitudes towards their work, the latter is concerned with the process through which teachers’ professional work may be improved. From this perspective, teachers may experience changes either in their intellectual or motivational development and/or in their general teaching practice.

Impact on Institutions

While most definitions of teacher development focus on the teacher, ongoing professional development and teacher education is not only important for teachers, but also have a significant impact on the success of the programs and institutions they work in and with (Richards & Farrell, 2005). According to a review of studies related to elementary school teachers carried out by REL Southwest (Yoon, Duncan, Lee, Scarloss, & Shapley, 2007), teachers that receive approximately 50 hours of teacher development were shown to increase their students’ scores on achievement tests by 21 percentile points. Likewise, Hanbury, Prosser, and Rickinson (2008) conclude from their study of the impact of professional development programs in higher education that benefits at a departmental level were related to: developments in educational practices, enhanced profile for teaching and learning, inter-departmental links, staff induction and mentoring. In the same way, Chalmers and Gardiner (2015) claim, based on their extensive review of studies concerning the impact of teacher development on teaching and learning, that “it is possible to evidence changes in teacher understanding, knowledge, skills and practices, and the consequential effect of these on student engagement and approaches to learning” (p. 83).

Impact on Professors

In regard to the impact on professors, Richards and Farrell (2005) explain that

The need for ongoing renewal of professional skills and knowledge is not a reflection of inadequate training but simply a response to the fact that not everything teachers need to know can be provided at pre-service level, as well as the fact that the knowledge base of teaching constantly changes. (p. 1)

Therefore, teacher development not only serves to update theoretical and practical knowledge among educators, but it also serves as an expansion of the learning that took place in their formal, pre-service training and education (Mizell, 2010). Hanbury et al. (2008) also confirm, through a review of several empirical and investigative studies, that teacher development can have positive benefits on teachers’ approaches to learning, especially regarding a move away from teacher-centered approaches and a move towards student-centered approaches.

Characteristics of Good Professional Development

In general, the following characteristics are considered as some of the most important for successful, good, quality, and effective teacher and professional development.

- It is connected to the particular context of the institution or program where it is implemented.

- It involves collaboration and cooperation among teachers as well as the specific educational community.

- It promotes the construction of a support system among teachers and the learning community.

- It is planned and carried out over time in a sustainable way.

- It places emphasis on the teacher as an active and reflective learner throughout the process.

- It involves active learning connected to program objectives and student learning. (Cohen & Hill, 2001; Desimone, Porter, Garet, Yoon, & Birman, 2002; Diaz-Maggioli, 2004; Generation Ready, 2013; SEDL, 1997; UNESCO, 2015)

Ultimately, “effective professional development should be understood as a job-embedded commitment that teachers make in order to further the purposes of the profession while addressing their own particular needs” (Diaz-Maggioli, 2004, p. 5). Teachers should, therefore, be placed at the center of their own professional development, perceived as life-long learners involved in activities that emphasize growth that will impact both their short-term and long-term teaching in the classroom and overall development as educators.

Based on the aforementioned needs and characteristics, the TPD designed was a hybrid model that incorporated elements of both teacher development as well as teacher training. As a hybrid model, it aimed to incorporate all the characteristics of quality teacher development. By doing so, it worked to ensure teachers were exposed to activities and opportunities that were directly relevant to their role as teachers in the EFL program who were implementing the new curriculum. Likewise, the model connected with their role as always evolving teachers in the field of education. In this way, teachers were able to receive and share knowledge, tools, and experiences to prepare them for and involve them in curriculum implementation while at the same time developing skills and acquiring knowledge that would serve them in future educational contexts.

Teacher Development Models

Aiming tobest incorporate the previously mentioned characteristics, teacher professional development has, over the last 20 years, gained a lot of momentum. As Villegas-Reimers (2003) argues: “for years, the only form of ‘professional development’ available to teachers was ‘staff development’ or ‘in-service training,’ usually consisting of workshops or short-term courses that would offer teachers new information on a particular aspect of their work” (p. 11). Today, teacher professional development is rather understood as extended and continuous improvement in which teachers should engage as they advance in their career. It is not a one-day, one-time learning unrelated experience, but the combination of progressive, diversified, and relevant learning that teachers gather throughout their work in teaching contexts. Different authors have proposed models or frameworks to guide institutions, programs, policy makers, and teachers to undertake teacher development aimed at improving teachers’ pedagogical foundations and practices and, therefore, improving students’ learning.

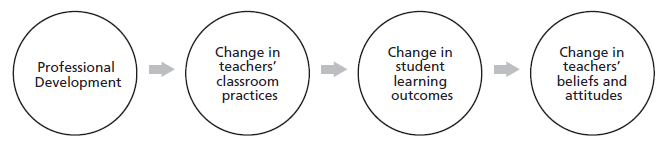

One of these authors is Guskey (2002), who places changes in students learning at the center of effective teacher development (p. 383). In this way, student change is a triggering factor for actual teacher change as represented by Figure 1.

Figure 1. Guskey’s Model of Teacher Change (2002, p. 383)

Guskey (2002) argues that “significant change in teachers’ attitudes and beliefs occurs primarily after they gain evidence of improvements in student learning (p. 383).” Regardless of the nature of the teacher development process carried out, this will be internalized by teachers when they observe evidence that their adjustments or implementations have worked and can be observed through changes in students’ learning. According to Guskey, without observation of these changes, teachers will make no use of the opportunities.

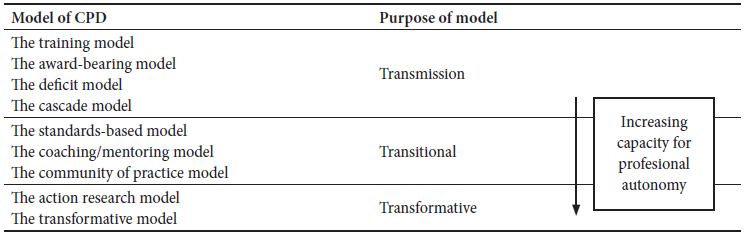

Likewise, Kennedy (2005) argues that since the purpose of continuing professional development is to empower teachers with the necessary foundations to become critical individuals who shape their own practice, who make informed decisions in the classroom, and who interpret policies with a critical eye, models for teacher development should be progressively selected and implemented depending on the needs and characteristics of the context. According to these ideas, teachers should be given the opportunity to increase their professional autonomy moving from controlling models to more constructive-creative ones as demonstrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Spectrum of CPD Models (Kennedy, 2005, p. 248)

The models in Figure 2 can be summarized in the following way (Kennedy, 2005, pp. 236-237):

- Transmission: The first two models in this category emphasize the teacher as being a passive receiver of information whether it is through training carried out by an expert (training model) or the completion of a course offered by an external institution (award-bearing model). The last two models place more responsibility on the teacher by asking the teacher to work on particular identified weaknesses (deficit model) or by participating in a professional development activity and sharing what was learned with fellow colleagues (cascade model).

- Transitional: The transitional models move away from focusing only on the teacher and begin to involve students as well as the teaching community. The standards-based model places importance on making empirical connections between teacher professional development (TPD) and students’ achievement. A bit different, the coaching/mentoring model and the community of practice model both stress teachers’ roles in their professional community as key. In the first, more experienced teachers are placed as mentors with less-experienced teachers. In the second, the entire teaching community works together to achieve a common TPD goal set by the community or institution.

- Transformational: The last two models mentioned by Kennedy push teachers to become researchers in their contexts (action-research model) and to transform themselves as teachers (transformative model). Both models require teachers to be aware of their practices and the conditions of their teaching-learning contexts and to use these aspects to better themselves as teachers.

Another model for teacher development is the one proposed by Diaz-Maggioli (2004) where teacher development is understood as a collaborative and continuous process in which teachers are expected to enrich and strengthen their practices by analyzing students’ needs and adjusting their teaching styles accordingly. What makes this model different from those previously mentioned is the conscious identification of teacher’s awareness of needs and lack of knowledge in establishing a teacher development framework. In other words, the more aware teachers are of their lacks in knowledge and their needs in improving teaching effectiveness, the more targeted and defined the professional development plan can be to meet these specific needs and lacks. Figure 3 represents “the Four Quadrants of the Teacher’s Choice Framework” which guides the design of a teacher development plan based on this model (Diaz-Maggioli, 2004).

Figure 3. The Four Quadrants of the Teacher’s Choice Framework (Diaz-Maggioli, 2004, p. 15)

According to Figure 3, there are four levels at which teachers can be placed depending on their own analysis and reflections on their strengths and areas of improvement. For instance, more experienced teachers, aware of their teaching foundations and context, can mentor less experienced colleagues, or they can prepare in-house training workshops or document their successful experiences as a point of reference for other teachers. The experienced teachers would classify at level one while less experienced teachers, not aware of their lacks and needs, would place at level four, with professional development consisting of participation in in-house workshops or processes of mentoring (Diaz-Maggioli, 2004).

In the same way, two of the most relevant factors that characterize this model are the expected willingness teachers should have for continuous improvement and the high value placed on collaborative work in the form of learning communities. For this model to be successful, teachers should demonstrate an intrinsic commitment and willingness to engage in development activities as well as a positive disposition towards collaborative work with peers in their context.

Teacher Development and Curriculum

According to UNESCO (2015),

Curriculum change is a dynamic and challenging process, and its success depends on all stakeholders having the capacity to develop or adopt a shared vision, positive attitudes and commitment. Moreover, they need to develop the necessary professional competencies in the various aspects of curriculum change. (para. 6)

Even so, there is sufficient evidence to argue that, when a new curriculum is implemented, few teachers actually change the way they are teaching to match what the curriculum calls for in terms of teaching practices in the classroom (Cohen & Hill, 2001; Cuban, 1990; Hardman & A-Rahman, 2014; Sargent, 2011; Yan, 2012), whether it be due to insufficient knowledge of the curriculum, lack of few professional development or training opportunities (Nunan, 2003), effects of poor leadership (Brooks & Gibson, 2012), or other contextual factors. Sargent (2011) reports on a study in China that looked at the effects of curriculum renewal on teachers’ beliefs and classroom practices, educational structures, and learning outcomes. Although teachers were utilizing some of the teaching methods required for the new curriculum to be effectively implemented, in the analysis of classroom practices post-curriculum implementation, data showed that there was still frequent use of traditional teaching methods such as memorization and recitation and lecture style teaching. Consequentially, professional development and training opportunities, such as peer observations, local trainings and workshops, research activities, and learning communities, for teachers were considered prerequisites to a successful implementation of the new curriculum proposed.

In order to reduce teacher resistance and better prepare teachers to implement a new curriculum, UNESCO (2015) focuses on the idea of capacity building: “The process of assisting an individual or group to gain insights, knowledge and experiences needed to solve problems and implement change” (para. 7). Capacity building activities, then, work to both inform all parties involved of the curriculum to be implemented through the improvement and development of necessary competencies and also to change the attitudes and perceptions of those teachers who may oppose the curriculum change. Through capacity building activities, teachers and teacher educators should be able to:

- understand their changing roles as curriculum changes;

- comprehend curriculum objectives and national curriculum standards;

- master subject matter and pedagogical skills to deliver subject-specific content;

- have a positive attitude to curriculum change and be an agent of change;

- break down isolation and develop team spirit;

- engage in continued professional learning and development. (UNESCO, 2015, para. 10)

Capacity building activities can include: training sessions, workshops, follow-up activities, and observations on which feedback is received, and so on, which in the best case scenario make up part of a customized teacher development program that meets the contextual needs of the educational institution and its community (teachers, learners, administrators, local community, etc.) (UNESCO, 2015).

In a study carried out with teachers in California, Cohen and Hill (2001) found that teacher development related to new curriculum and policy implementation was more effective when it focused on activities aimed at developing pedagogical strategies directly related to the curriculum and involved materials that could be used with the curriculum in question rather than activities that focused on generalized pedagogical strategies or materials. In the same way, according to a study in Canada, teachers involved in the implementation of a new curriculum acknowledge the importance and the positive impact curriculum-linked professional development can have (Brooks & Gibson, 2012).

Similarly, when incorporating elements of the new curriculum into teacher development activities, Penuel, Fishman, Yamaguchi, and Gallagher (2007) highlight the advantages of having teachers work collaboratively and participate as a group to foster a system of trust and support as they navigate the new curriculum together. Teachers in Brooks and Gibson’s (2012) study also highlighted the importance of having this support system and collegial community as they engaged in professional development for new curriculum implementation.

Throughout the process of designing and implementing the TPD for the EFL program in question, capacity building was a key element in designing and carrying out activities and affording experiences to participating teachers. Likewise, the curriculum design team was conscious of engaging teachers in collaborative activities as well as using elements of the newly designed curriculum in as many of the teacher development activities as possible. This aimed to ensure teacher exposure to and experience with the curriculum before and during its implementation in order to provide teachers with more personalized and relevant skills and tools together with a network of peer support.

Teacher Development Program Linked to Curriculum Renewal

Bearing in mind the various models of teacher development in existence, one can see that the model of teacher development program for curriculum renewal designed here does not limit itself to any one model, but rather incorporates elements of various models such as the training and coaching/mentoring models mentioned by Kennedy (2005), Guskey’s (2002) student centered model, and Diaz-Maggioli’s (2004) teacher-centered model in order to create a model that could more effectively meet the needs of the institution, program, teachers, and students. It is a curriculum renewal-linked professional development program that focuses on “how to enact pedagogical strategies, use materials, and administer assessments associated with particular curricula” (Penuel et al., 2007, p. 928).

In this way, the model being described here combines and integrates elements of various models and aims to find an adequate balance between teacher-centered and context-specific teacher development in such a way that teachers are able to expand their formal knowledge, engage in job-embedded learning opportunities, participate in reflective teaching activities, and carry out transformative practice, all of which address both the immediate needs related to the new curriculum as well as the short and long-term professional needs of teachers.

Process of Designing Teacher Development Program

In designing the curriculum renewal linked teacher development program, the following steps were followed:

- Execution of a two-pronged needs analysis with teachers and students

- Exploration of existing frameworks for curriculum implementation

- Creation of objectives for the teacher development framework

- Choice and design of teacher development activities

- Confirmation of final program design

- Implementation of TPD

Structure of Teacher Development Program

In order to achieve the general objectives set forth, the teacher development for curriculum renewal program included a variety of capacity building activities:

- EFL program meetings with all teachers in the program

- Introductory curriculum open houses

- Teacher-led meetings

- In-house workshops

- Teacher presentations of their best practices

- Workshops by textbook authors

- Workshops by international experts

- Reflective article discussions

- Teacher observations and feedback sessions

Overall, the program was organized in such a way that every semester began and ended with a general, but tailored activity for all teachers as well as in a way that allowed for constant and individualized activities throughout the semester.

Types of Activities Used in the Program

In order to provide teachers with as many opportunities as possible to prepare them for and guide them through curriculum implementation, a variety of activities were included in the TPD including both teacher-led as well as expert-led activities.

First, information sessions were included in the program at several moments, used principally to share important and succinct information with teachers and the institutional community. These sessions were mostly occupied with presenters explaining and presenting information to teachers with some time allotted for short question and answer sessions.

Likewise, there were many workshops included throughout the teacher development program. Richards and Farrell (2005) describe workshops as “one of the most powerful and effective forms of teacher-development activity” (p. 25) as they allow and create ideal spaces for receiving input from expert, exploring practical classroom applications, increasing teachers’ motivation, developing collegiality, supporting innovation, being flexible in terms of organization, and functioning in short-term time frames. Aware of these benefits, the program implemented several types of workshops, designed both internally and externally. Internally designed workshops included those that were: institutional led, teacher led, and curriculum design team led, while externally designed workshops included those that were led by invited textbook authors, skills experts, and teacher development experts in the EFL field.

At the same time, there were several reflective type sessions incorporated into the teacher development program as spaces for teachers to be exposed to learning moments that focused on reflection and discussion with colleagues guided by an internal colleague and/or an external expert where reflection was seen as “the process through which teachers comprehend and learn from their teaching experiences and assign significance to their teaching practices” (Zhao, 2012, p. 57). All of these sessions aimed to encourage teachers to reflect critically on their practices in the classroom both during and after the curriculum implementation.

In the same way, several opportunities for both individual teacher observations as well as peer observations were included in the program. Individual teachers were observed by curriculum design team members and also by their level coordinators in the program, not to evaluate their teaching, but to observe how the new curriculum was being implemented and identify any areas that might need attention. These observations helped to assure that the needs of teachers in the early stages of curriculum implementation were continued to be met within the TPD.

Peer observations are

collaborative, developmental activit[ies] in which professionals offer mutual support by observing each other teach; explaining and discussing what was observed; sharing ideas about teaching; gathering student feedback on teaching effectiveness; reflecting on understandings, feelings, actions and feedback and trying out new ideas. (Bell as cited in Bell & Mladenovic, 2008, p. 736)

They can help create a sense of community among teachers by allowing them to give and receive support from their colleagues, which is important for teachers involved in new curriculum implementation (Brooks & Gibson, 2012). All of the peer observations carried out in this TPD were designed for developmental purposes rather than evaluative, just as the individual teacher observations, which were to try and lower resistance to observations as well as avoid any possible negative perceptions of this process (Lomas & Nicholls, 2005). Likewise, peer observations were used in a way similar to those in Bell and Mladenovic’s study (2008), which allowed teachers to discuss the observations and any challenges related to them in a collaborative and supportive environment.

Overall, the activities included in the TPD were based on the curriculum to be implemented as this connection makes the professional development more meaningful and helpful (Brooks & Gibson, 2012).

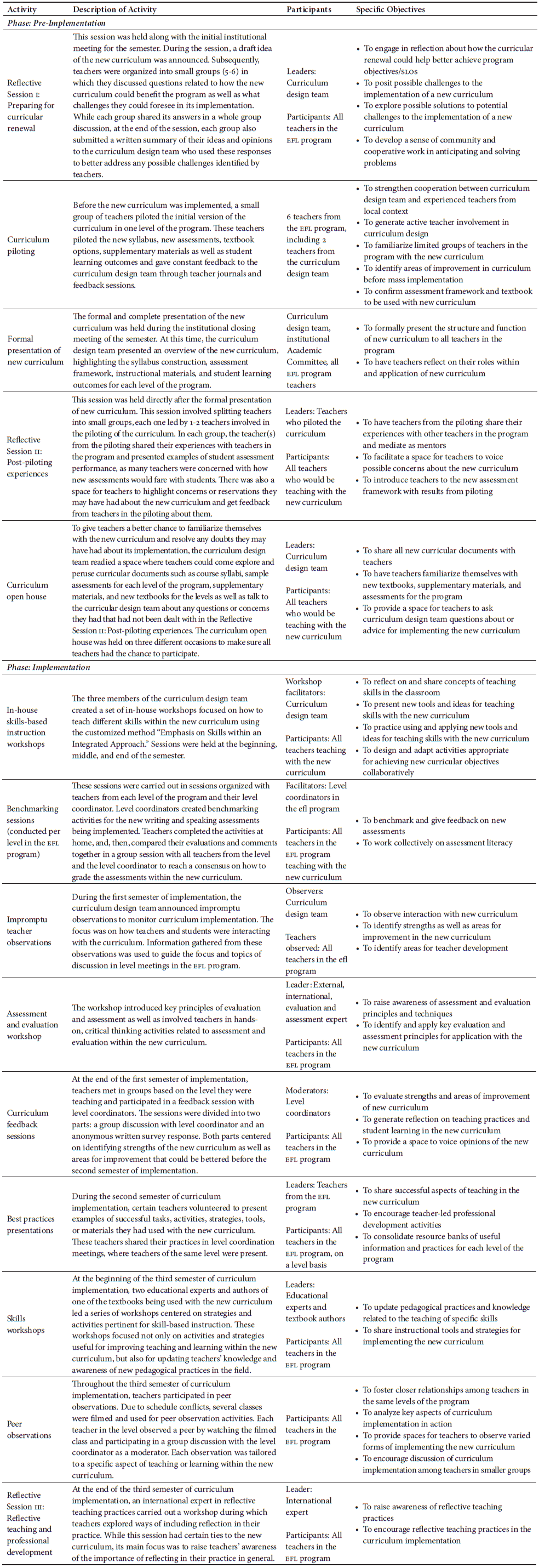

Table 1 shows the TPD designed and implemented with activities and objectives according to the phase during which they were carried out: pre-implementation, implementation, or post-curriculum implementation.

Table 1. Teacher Development Program Linked to Curriculum Renewal

Impact in the EFL Program

In many cases, institutions and programs bring in external experts to implement TPDs or activities (Kennedy, 2005). However, in the case of this TPD, the institution created the framework internally, relying primarily on local teachers and staff to design and implement development activities and counted on external experts on very few occasions.

With the use of this model, the institution was not only able to directly prepare its professors for the curriculum renewal, but was also able to observe a variety of positive effects related to the implementation of the teacher development program linked to curriculum renewal.

The major positive effects of the TPD observed were: increased consistency in curriculum implementation by teachers, increased understanding of new professional and practical roles of teachers within the new curriculum, and a new vision of coordination meetings within the program.

In terms of the impact on teachers, one of the most important effects observed was the alignment of teachers’ understanding and implementation of the new curriculum. At the same time, and perhaps more importantly, teachers’ conceptualization and practice of their role within said curriculum also became clearer. Both of these effects were noted in the observations carried out as part of the framework as well as in formal and informal feedback sessions with teachers. Not only did teachers feel they better understood how to teach within the new curriculum, but they also felt more comfortable in their role as teachers. Below are a few comments from teachers on a questionnaire administered in the curriculum feedback sessions that reflect the impact the TPD had on them:

- I am getting familiar with this new methodology and I find it an enriching experience.

- It’s good when as a teacher your teaching practice is enriching and have wonderful opportunity to share ideas and opinions from your coordinator and colleagues teaching the same level.

- I learned new strategies to isolate the skills.

- I think this is a worthwhile experience that has contributed enormously to my professional development.

- This was a great semester of growth for me as a teacher.

Similarly, through the implementation of this model, teachers became more conscious of the local and contextual curricular and teacher development needs that had been identified together with those needs that were being met through the new curriculum itself. This awareness of needs was generated specifically through the involvement of professors in the construction of the TPD and the activities that it involved. In a focus group at the end of the first semester of curriculum implementation, teachers concluded:

- This approach [to curriculum implementation] considers different learning styles, highlighting areas that one is most experienced in and challenging you to work on those areas where you have difficulty.

- The curriculum implementation has represented a challenge for teachers in that it obligates them to rethink their teaching methodology and strengthen their own weaknesses in the skills (reading, writing, listening, and speaking) to better favor an integral learning experience for students.

Likewise, in the end of semester program evaluation focus groups, informal feedback sessions with coordinators, and wrap-up questionnaires after the implementation of the development framework, teachers expressed the feeling that one of the strengths of the program had become the professional development activities and support for teachers offered by the program. Professors also commented that, due to the program, they were exposed to a constant process of evaluation and self-evaluation focused on improvement in their teaching practice. These comments demonstrate the positive effects the framework had on teachers’ perceptions of the program they work in as well as the program’s concern for their professional growth.

In the same way, the TPD developed initiated positive changes in the overall structure of the coordination and faculty meetings carried out not only for the EFL program, but for the language institute as well. Thanks to the changes within the TPD, level coordination meetings were strengthened and took on a more practical, collaborative, and reflective focus where coordinators and teachers not only discussed important information but also shared ideas and challenges, reflected on ways to improve the level, and worked on collaborative projects.

Conclusions

The teacher development program linked to curriculum renewal designed and presented in this paper represents one EFL program’s attempt to prepare teachers for implementing a new curriculum, make the implementation more successful, and, at the same time, engage teachers in professional development activities and opportunities. While no TPD is perfect and can cover everything, through the careful combination and integration of key aspects of various models of teacher and professional development, institutions and programs can design and implement models that best meet their local and contextual needs to generate positive change among faculty, students, programs, and even the institution at large.

References

Bailey, K. M., Curtis, A., Nunan, D., & Fan, D. (2001). Pursuing professional development: The self as source. Beijing, CN: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.

Bell, A., & Mladenovic, R. (2008). The benefits of peer observation of teaching for tutor development. Higher Education, 55(6), 735-752. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-007-9093-1.

Brooks, C., & Gibson, S. E. (2012). Teachers’ perspectives on the effectiveness of a locally planned professional development program for implementing new curriculum. Teacher Development, 16(1), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2012.667953.

Chalmers, D., & Gardiner, D. (2015). An evaluation framework for identifying the effectiveness and impact of academic teacher development programmes. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 46, 81-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2015.02.002.

Cohen, D. K., & Hill, H. C. (2001). Learning policy: When state education reform works. New Haven, US: Yale University Press. https://doi.org/10.12987/yale/9780300089479.001.0001.

Council of Europe. (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Cuban, L. (1990). Reforming again, again, and again. Educational Researcher, 19(1), 3-13. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X019001003.

Desimone, L. M., Porter, A. C., Garet, M. S., Yoon, K. S., & Birman, B. F. (2002). Effects of professional development on teachers’ instruction: Results from a three-year longitudinal study. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 24(2), 81-112. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737024002081.

Diaz-Maggioli, G. (2004). Teacher-centered professional development. Alexandria, US: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Evans, L. (2002). What is teacher development? Oxford Review of Education, 28(1), 123-137. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980120113670.

Generation Ready. (2013). Raising student achievement through professional development [White paper]. Retrieved from http://www.generationready.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/PD-White-Paper.pdf.

Guskey, T. R. (2002). Professional development and teacher change. Teachers and Teaching, 8(3), 381-391. https://doi.org/10.1080/135406002100000512.

Hanbury, A., Prosser, M., & Rickinson, M. (2008). The differential impact of UK accredited teaching development programmes on academics’ approaches to teaching. Studies in Higher Education, 33(4), 469-483. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802211844.

Hardman, J., & A-Rahman, N. (2014). Teachers and the implementation of a new English curriculum in Malaysia. Language, Culture, and Curriculum, 27(3), 260-277. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2014.980826.

Heystek, J., & Terhoven, R. (2015). Motivation as critical factor for teacher development in contextually challenging underperforming schools in South Africa. Professional Development in Education, 41(4), 624-639. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2014.940628.

Kennedy, A. (2005). Models of continuing professional development: A framework for analysis. Journal of In-service Education, 31(2), 235-250. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674580500200277.

Lomas, L., & Nicholls, G. (2005). Enhancing teaching quality through peer review of teaching. Quality in Higher Education, 11(2), 137-149. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538320500175118.

Mizell, H. (2010). Why professional development matters. Oxford, US: Learning Forward. Retrieved from https://learningforward.org/docs/pdf/why_pd_matters_web.pdf.

Nunan, D. (2003). The impact of English as a global language on educational policies and practices in the Asia-Pacific region. TESOL Quarterly, 37(4), 589-613. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588214.

Penuel, W. R., Fishman, B. J., Yamaguchi, A., & Gallagher, L. P. (2007). What makes professional development effective? Strategies that foster curriculum implementation. American Educational Research Journal, 44(4), 921-958. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831207308221.

Richards, J. C., & Farrell, T. S. C. (2005). Professional development for language teachers: Strategies for teacher learning. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667237.

Sargent, T. C. (2011). New curriculum reform implementation and the transformation of educational beliefs, practices, and structures: A case study of Gansu Province. Chinese Education and Society, 44(6), 47-72. https://doi.org/10.2753/CED1061-1932440604.

SEDL. (1997). Professional development for language teachers implementing the Texas essential knowledge and skills for languages other than English. Austin, US: Texas Education Agency. Retrieved from http://www.sedl.org/loteced/products/profdev.pdf.

UNESCO. (2015). Training tools for curriculum development: A resource pack (Module 6). Retrieved from http://www.ibe.unesco.org/fileadmin/user_upload/COPs/Pages_documents/Resource_Packs/TTCD/sitemap/Module_6/Module_6.html.

Villegas-Reimers, E. (2003). Teacher professional development: An international review of the literature. Paris, FR: UNESCO, International Institute for Educational Planning.

Wiggins, G. P., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Yan, C. (2012). “We can only change in a small way”: A study of secondary English teachers’ implementation of curriculum reform in China. Journal of Educational Change, 13(4), 431-447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-012-9186-1.

Yoon, K. S., Duncan, T., Lee, S. W.-Y., Scarloss, B., & Shapley, K. L. (2007). Reviewing the evidence on how teacher professional development affects student achievement (Issues & Answers Report, REL 2007 - No. 033). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Regional Educational Laboratory Southwest. Retrieved from http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs.

Zhao, M. (2012). Teachers’ professional development from the perspective of teaching reflection levels. Chinese Education and Society, 45(4), 56-67. https://doi.org/10.2753/CED1061-1932450404.

About the Authors

Erica Ferrer Ariza is a teacher-coordinator of the MA in English language teaching program at the Universidad del Norte. Her research interests include curriculum development and discourse analysis. She holds a BA in Education (Universidad de Atlántico, Colombia) and an MA in language teaching and learning (University of Liverpool, UK).

Paige M. Poole holds an MA in TESOL studies (University of Leeds, England). She currently works as the coordinator of the specialized English programs and is a teacher in the English for international relations program at Universidad del Norte.

References

Bailey, K. M., Curtis, A., Nunan, D., & Fan, D. (2001). Pursuing professional development: The self as source. Beijing, CN: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.

Bell, A., & Mladenovic, R. (2008). The benefits of peer observation of teaching for tutor development. Higher Education, 55(6), 735-752. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-007-9093-1.

Brooks, C., & Gibson, S. E. (2012). Teachers’ perspectives on the effectiveness of a locally planned professional development program for implementing new curriculum. Teacher Development, 16(1), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2012.667953.

Chalmers, D., & Gardiner, D. (2015). An evaluation framework for identifying the effectiveness and impact of academic teacher development programmes. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 46, 81-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2015.02.002.

Cohen, D. K., & Hill, H. C. (2001). Learning policy: When state education reform works. New Haven, US: Yale University Press. https://doi.org/10.12987/yale/9780300089479.001.0001.

Council of Europe. (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Cuban, L. (1990). Reforming again, again, and again. Educational Researcher, 19(1), 3-13. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X019001003.

Desimone, L. M., Porter, A. C., Garet, M. S., Yoon, K. S., & Birman, B. F. (2002). Effects of professional development on teachers’ instruction: Results from a three-year longitudinal study. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 24(2), 81-112. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737024002081.

Diaz-Maggioli, G. (2004). Teacher-centered professional development. Alexandria, US: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Evans, L. (2002). What is teacher development? Oxford Review of Education, 28(1), 123-137. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980120113670.

Generation Ready. (2013). Raising student achievement through professional development [White paper]. Retrieved from http://www.generationready.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/PD-White-Paper.pdf.

Guskey, T. R. (2002). Professional development and teacher change. Teachers and Teaching, 8(3), 381-391. https://doi.org/10.1080/135406002100000512.

Hanbury, A., Prosser, M., & Rickinson, M. (2008). The differential impact of UK accredited teaching development programmes on academics’ approaches to teaching. Studies in Higher Education, 33(4), 469-483. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802211844.

Hardman, J., & A-Rahman, N. (2014). Teachers and the implementation of a new English curriculum in Malaysia. Language, Culture, and Curriculum, 27(3), 260-277. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2014.980826.

Heystek, J., & Terhoven, R. (2015). Motivation as critical factor for teacher development in contextually challenging underperforming schools in South Africa. Professional Development in Education, 41(4), 624-639. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2014.940628.

Kennedy, A. (2005). Models of continuing professional development: A framework for analysis. Journal of In-service Education, 31(2), 235-250. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674580500200277.

Lomas, L., & Nicholls, G. (2005). Enhancing teaching quality through peer review of teaching. Quality in Higher Education, 11(2), 137-149. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538320500175118.

Mizell, H. (2010). Why professional development matters. Oxford, US: Learning Forward. Retrieved from https://learningforward.org/docs/pdf/why_pd_matters_web.pdf.

Nunan, D. (2003). The impact of English as a global language on educational policies and practices in the Asia-Pacific region. TESOL Quarterly, 37(4), 589-613. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588214.

Penuel, W. R., Fishman, B. J., Yamaguchi, A., & Gallagher, L. P. (2007). What makes professional development effective? Strategies that foster curriculum implementation. American Educational Research Journal, 44(4), 921-958. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831207308221.

Richards, J. C., & Farrell, T. S. C. (2005). Professional development for language teachers: Strategies for teacher learning. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667237.

Sargent, T. C. (2011). New curriculum reform implementation and the transformation of educational beliefs, practices, and structures: A case study of Gansu Province. Chinese Education and Society, 44(6), 47-72. https://doi.org/10.2753/CED1061-1932440604.

SEDL. (1997). Professional development for language teachers implementing the Texas essential knowledge and skills for languages other than English. Austin, US: Texas Education Agency. Retrieved from http://www.sedl.org/loteced/products/profdev.pdf.

UNESCO. (2015). Training tools for curriculum development: A resource pack (Module 6). Retrieved from http://www.ibe.unesco.org/fileadmin/user_upload/COPs/Pages_documents/Resource_Packs/TTCD/sitemap/Module_6/Module_6.html.

Villegas-Reimers, E. (2003). Teacher professional development: An international review of the literature. Paris, FR: UNESCO, International Institute for Educational Planning.

Wiggins, G. P., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Yan, C. (2012). “We can only change in a small way”: A study of secondary English teachers’ implementation of curriculum reform in China. Journal of Educational Change, 13(4), 431-447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-012-9186-1.

Yoon, K. S., Duncan, T., Lee, S. W.-Y., Scarloss, B., & Shapley, K. L. (2007). Reviewing the evidence on how teacher professional development affects student achievement (Issues & Answers Report, REL 2007 - No. 033). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Regional Educational Laboratory Southwest. Retrieved from http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs.

Zhao, M. (2012). Teachers’ professional development from the perspective of teaching reflection levels. Chinese Education and Society, 45(4), 56-67. https://doi.org/10.2753/CED1061-1932450404.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Abir El Shaban, Joy Egbert. (2018). Diffusing education technology: A model for language teacher professional development in CALL. System, 78, p.234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.09.002.

2. Darío Luis Banegas, Kathleen Corrales, Paige Poole. (2020). Can engaging L2 teachers as material designers contribute to their professional development? findings from Colombia. System, 91, p.102265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102265.

3. Walter Sengai, Matseliso Mokhele. (2025). Exploring Teachers’ Perspectives of Professional Development Opportunities During the Implementation of History 2166 Syllabus Reforms in Zimbabwe. International Journal of Educational Development in Africa, 10(Supplementary Issue) https://doi.org/10.25159/2312-3540/17457.

4. Juan Carlos Torres-Rincon, Liliana Marcela Cuesta-Medina. (2019). Situated Practice in CLIL: Voices from Colombian Teachers. GiST Education and Learning Research Journal, 18, p.109. https://doi.org/10.26817/16925777.456.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

Copyright (c) 2018 PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.