Teachers’ Perceptions About Oral Corrective Feedback and Their Practice in EFL Classrooms

Palabras clave:

Corrective feedback, EFL, perceptions, practice. (en)Descargas

Teachers’ Perceptions About Oral

Corrective Feedback and Their Practice in EFL Classrooms

Percepciones de los docentes acerca

de la retroalimentación

correctiva y su práctica en las aulas de inglés como

lengua extranjera

Edith

Hernández Méndez*

María

del Rosario Reyes Cruz**

Universidad de

Quintana Roo, Mexico

This article was received on December 6, 2011, and

accepted on May 14, 2012.

Corrective feedback has been discussed mainly in

second language acquisition contexts, but less has been done concerning

corrective feedback in foreign language settings. In this descriptive study,

conducted at a Mexican university, our aims were to identify the perceptions of

instructors of English as a foreign language about corrective feedback and its

actual practice in their classrooms. A semi-structured interview and a

questionnaire were used to collect the data. The results show that teachers in

general have a positive perception of oral corrective feedback. However, some

consider it as optional because instructors are very concerned with

students’ feelings and emotions. Unfocused oral corrective feedback and

implicit strategies are predominant in practice. Corrective feedback provided

by the instructor is preferred to that provided by peers. Self-correction is the

least popular.

Key words: Corrective

feedback, EFL, perceptions, practice.

La

retroalimentación correctiva se ha discutido principalmente en contextos

de adquisición de segundas lenguas, pero poco se ha hecho en el

área de lenguas extranjeras. Esta investigación descriptiva,

realizada en una universidad mexicana, tuvo como objetivo identificar las

percepciones de profesores de inglés como lengua extranjera sobre

retroalimentación correctiva y su práctica. Para la

recolección de datos se usaron una entrevista semiestructurada

y un cuestionario. Los resultados muestran que si bien los profesores en

general tienen una percepción positiva sobre la retroalimentación

correctiva oral, algunos la consideran opcional, pues les preocupan los

sentimientos y emociones de los estudiantes. En la práctica

predominan la

retroalimentación correctiva oral no enfocada y las estrategias

implícitas. Asimismo, se prefiere la retroalimentación correctiva

que ofrece el docente y la autocorrección es la menos común.

Palabras clave: inglés

lengua extranjera, percepciones, práctica, retroalimentación

correctiva.

Introduction

Errors in most cultures are seen as something we

should avoid or prevent, as errors can be the cause even of unfortunate events.

To deal with them, then, is not easy. When talking about errors in language

learning or language acquisition, we cannot help but become part of a very

controversial topic, either on the theoretical or methodological (pedagogical)

side.

Han (2008) suggests that error correction implies an

evident and direct correction, whereas corrective feedback is a more general

way of providing some clues, or eliciting some correction, besides the direct

correction made by the teacher. For the sake of clarity, we will refer to

correction as corrective feedback in this paper.

Although the role of corrective feedback has been

discussed from both theoretical and methodological viewpoints, one wonders:

What occurs in practice in real foreign language classrooms? How are these

theories and methodologies translated and implemented with real language

learners? These questions have been around for some decades now, and problems

with regard to the use of corrective feedback or its absence in the language

classroom have been identified, to wit: a) the inconsistency, ambiguity, and

ineffectiveness of teachers’ corrections (Allwright,

1975; Chaudron, 1977; Long, 1977); b) ambiguous,

random and unsystematic feedback on errors by teachers (Lyster

& Mori, 2006); c) acceptance of errors for fear of interrupting

communication; and d) a wide range of learner error types addressed as

corrective feedback (Lyster & Ranta,

1997).

Corrective feedback (CF) has been discussed mainly in

second language acquisition contexts, but less has been done in foreign

language settings. Therefore, this paper reports the findings from a study

conducted at a Mexican university where English as a Foreign Language is taught

to all undergraduate students who

have, as a graduation requirement, a need to cover four prescribed levels of

English (from Introduction to Intermediate). Our aims were to identify the EFL

(English as a Foreign Language) instructors’ perceptions about CF and its

actual practice in their classrooms. Our specific questions were: What are the

teachers’ perceptions about corrective feedback? What are the

teachers’ self-reported ways of implementing corrective feedback in their

classrooms?

This paper is organized into three sections. First, an

overview of CF in literature is presented. We discuss mainly the changing

viewpoints with regard to CF, and then we describe strategies employed to

provide oral corrective feedback, considering the provider, the frequency of

provision, the type of error, and the type of strategy. The next section

includes a description of the method used to conduct this descriptive study.

The research findings as well as a discussion and interpretation make up

section 3. Data from both the questionnaire and the interview are integrated in

the discussion. Finally, a conclusion and some suggestions are offered for EFL

teaching.

Corrective

Feedback

The term corrective feedback has been defined at

different times in a very similar way. One of the earliest definitions is that

of Chaudron (1977), who considers it as “any

reaction of the teacher which clearly transforms, disapprovingly refers to, or

demands improvement of the learner utterance” (p. 31). More recently,

Ellis, Loewen and Erlam

(2006) stated that:

Corrective feedback takes the form of responses to

learner utterances that contain error. The responses can consist of (a) an

indication that an error has been committed, (b) provision of the correct

target language form, or (c) meta-linguistic information about the nature of

the error, or any combination of these. (p. 340)

Although all these definitions include the

learners’ and teacher’s participation, and thus, a classroom as the

setting where CF takes place, this can also occur in naturalistic settings where

native or non-native speakers can provide it.

Interestingly, in the foreign language contexts, Sheen

(2011) points out that not all CF occurs because of a communication breakdown;

teachers can use it to draw the learners’ attention to form even in those

situations where they comprehend each other. This means that CF can carry

negotiation of meaning and negotiation of form as well.

The role and importance of CF in EFL pedagogy can vary

from teacher to teacher. This may depend on their previous education and

training, teaching experience, and their own experience as language learners,

amongst others. CF is a very controversial issue in this regard. Perspectives

toward errors have gone from the extreme of non-acceptance and preventing them

at all cost, to more permissive perspectives in which errors are seen as part

of the language development.

Next, we present a summary of the main issues

concerned with the provision of oral CF.

Types of Oral

Corrective Feedback Strategies

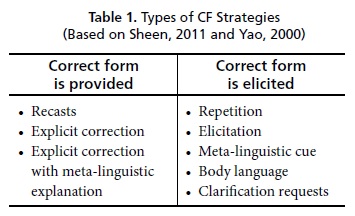

Sheen (2011) classifies CF strategies into seven

types; Yao (2000) added body language as another strategy. Table

1 illustrates this and a more detailed study follows.

Recasts

“A recast is a reformulation of the

learner’s erroneous utterance that corrects all or part of the

learner’s utterance and is embedded in the continuing discourse”

(Sheen, 2011, p. 2). Recasts can be

partial or whole (only a part or the whole utterance is reformulated,

respectively). They can be didactic or conversational. The former is a partial

or whole reformulation that draws the learner’s attention to the error

made. The purpose is merely pedagogical. On the other hand, the conversation

recasts take place when there is a breakdown in communication, and the

corrector reformulates to verify if he comprehends what is intended. The

following dialogs illustrate this strategy:

S: I have 20 years old.1

T: I am

(Partial didactic recast)

S: I can lend your pen? T: What?

S: Can I lend your pen?

T: You mean, Can I borrow

your pen?

(Conversation recast)

Explicit Correction

The correct form is provided by the instructor. Sheen

(2011) indicates that phrases such as “It’s not X but Y”,

“You should say X”, “We say X not Y” usually accompany

this treatment. Example:

S: She go to school every

day.

T: It’s not “she go”, but “she

goes”.

(Sample of our own)

Explicit Correction

with Meta-Linguistic Explanation

The correct form and a meta-linguistic comment on the

form are provided. Let us see the following example:

S: Yesterday rained.

T: Yesterday it rained. You need to include the

pronoun “it” before the verb. In English we need “it”

before this type of verb related to weather.

(Sample taken from Sheen, 2011)

Repetition

In order to elicit the correct form, the wrong

utterance is repeated (partially or entirely). We suggest that this repetition

is generally accompanied by some intonation change emphasizing the error or in

a question form. Example:

S: I eated a sandwich.

T: I EATED a sandwich?

(Sample of our own)

Elicitation

This strategy takes place when there is a repetition

of the learners’ erroneous utterance up to the point when the error occurs.

This way self-correction is promoted. Example:

S: When did you went to the

market?

T: When did you...?

(Sample of our own)

Meta-Linguistic Cue

This strategy is similar to “explicit correction

with meta-linguistic explanation” to some extent, but it differs in that

there is a meta-linguistic comment by the corrector, but the correct form is

not provided. Self-correction is then encouraged. Example:

S: There were many woman in

the meeting.

T. You need plural.

(Sample of our own)

Body Language

The corrector uses either a facial expression or a

body movement to indicate that what the student said is incorrect. A frown,

head shaking, or finger signaling “no” can be observed (Yao, 2000).

Example:

S: She doesn’t can swim.

T: Mmm. (T. Shakes her head=

no).

(Sample of our own)

These strategies can be classified into those which

provide some input (correct form is provided) or the learner is prompted to

generate some output by himself (correct form is elicited).

Clarification

Requests

When the learner’s utterance has an error and a

clarification is requested: “Sorry?”, “Pardon me?” I

don’t understand what you just said. Example:

S: How many years do you have?

T: Sorry?

(Sample of our own)

Another useful categorization of strategies is that

which divides them into explicit CF

and implicit CF. With explicit, there

is an overt linguistic signal in the correction; with implicit the correction

is prompted or elicited without an overt linguistic signal. The preference for

one type or the other may depend on the teacher.

A very important factor to consider when choosing the

CF strategy is its effect on learner

uptake, which is defined by Lyster and Ranta (1997) as “a student utterance that immediately

follows the teacher’s feedback with the intention of drawing attention to

some aspect of the student’s initial utterance” (p. 49). In other

words, it’s the learner’s response to the CF received. He has to

choose: to repair or not to repair. Lyster and Ranta call these actions: repair and needs repair. In the

former, the learner corrects after receiving CF; in the latter, the learner may

acknowledge the correction (but without any correction) or just continue

talking.

Focused and unfocused

CF is another way of providing correction in the classroom setting. The former refers

to the “intensive corrective feedback that repeatedly targets one or a

very limited number of linguistic features”; unfocused CF is

“extensive corrective feedback that targets a range of grammatical

structures” (Sheen, 2011, p. 8). We can also understand unfocused CF as

that feedback that targets any feature of a language level: pronunciation,

grammar, semantics, pragmatics; and many structures, phonemes, and categories

at the same time.

Another issue regarding how to provide CF has to do

with the dichotomy individual vs. group

correction. Some instructors consider individual correction as an activity

that may prevent further participation in the classroom because they see CF as

an inhibitor, as something that may damage learners’ feelings; therefore,

they favor group correction. A differing view is that individual correction

seems more effective, as the learners addressed becomes aware of their errors,

notices the error, and corrects. When using group correction, many students do

not even acknowledge the errors they made and there is no repair at all.

Although the literature on corrective feedback

generally does not discuss the possibility that the strategies to provide CF

can vary, depending on the learners’ language proficiency and

meta-linguistic vocabulary, in practice this is something that can occur. For

instance, it may be difficult to provide explicit correction with

meta-linguistic explanation to beginners in the target language, and probably

more time would be wasted than that required for another strategy such as body

language. This is another important decision for the language instructor, who

needs not only a range of strategies, (examples provided previously), but also

the experience of how to put them into practice with real language learners and

their particular individual differences.

In the theoretical and pedagogical grounds CF has been

a very controversial topic. Loewen, Li, Fei, Thomson, Nakatsukasa, Ahn, and Chen (2009) claim that this controversy can be

better understood in terms of meaning-focused

instruction versus form-focused

instruction. The former assumes that second language (L2) acquisition

occurs unconsciously and implicitly like first language acquisition (L1) does.

Advocates of this view claim that overt attention to linguistic form is not

needed, and they see corrective feedback as ineffective (e.g., Krashen, 1982; Newmark & Reibel, 1968; Schwartz, 1993; Terrell, 1977; Truscott,

1999, all cited by Loewen et al. 2009). Krashen (1982), one of its proponents, suggests that CF is

useless and potentially harmful.

The meaning-focused instruction has been questioned

with regard to its effectiveness. Research suggests that learners’

production shows grammatical inaccuracy even after years of exposure to the

target language. This situation has been associated with a lack of noticing and

practicing linguistic forms on behalf of the learners. Findings suggest,

therefore, that form-focused instruction can benefit language learners.

Form-focused instruction is defined by Ellis (2001, p. 1) as “any planned

or incidental instructional activity that is intended to induce language

learners to pay attention to linguistic forms.” This last instruction

supports the use of CF in language learning.

When to Use CF?

CF can be provided immediately after the error has

been made, or it can be delayed until later, after the communicative activity

the learners are engaged in is finished. The main distinction many instructors

make is between fluency and accuracy or if the activity involves negotiation of

meaning or negotiation of form. Instructors who practice a focus on meaning

instruction and encourage fluency in their classrooms prefer to delay CF.

However, if their instruction follows a focus on form and they want to encourage

accuracy, then both immediate and delayed CF are encouraged.

Important also to consider in instructional settings

is the frequency with which teachers use CF in their classes. Too much

correction can sometimes have a negative effect on the learners’

attitudes or performances; whereas too little feedback can also be perceived by

learners as a hindrance for efficient and effective language learning. Finding

the right balance as regards the amount of CF is, therefore, not an easy task.

Error Types

When correcting, it is paramount to identify the type

of error the learners make because it is not always the case teachers want or

need to correct everything. Errors have been categorized by Mackey, Gass and McDonough (2000) and Nishita

(2004), cited by Yoshida (2008) as:

• Morphosyntactic error: Learners incorrectly use word

order, tense, conjugation and particles.

• Phonological error: Learners

mispronounce words (or we suggest it could also include suprasegmental

errors such as stress and intonation).

• Lexical error: Learners use vocabulary

inappropriately or they code-switch to their first language because of their

lack of lexical knowledge.

• Semantic and pragmatic error: The

misunderstanding of a learner’s utterance, even if there are no

grammatical, lexical or phonological errors.

When dealing with errors, language instructors have to

make many decisions and one of them is the type of error to correct. However,

sometimes some types of errors are neglected to some extent, or only the most

“serious” errors are corrected. That is, there are errors that

probably do not hinder comprehension between the language instructor and the

learner, but they are errors that in a real world setting might affect

communication with other speakers who are not familiar with foreign accents, or

who are not tolerant with nonnative speakers. Thus, identifying and targeting

the types of errors that are relevant and essential to become a successful EFL

learner is another complex task for the instructor.

CF Providers in the

Classroom Setting

Considering the participant(s) in the corrective

feedback interaction, the following possibilities can be observed:

Self-correction is possible when the learner realizes that s/he has

committed an error and repairs it by providing a correct form. Self-correction

seems to be preferred to correction provided by others because it is

face-saving and allows the learner to play an active role in the corrective

event. Self-correction plays a central role in the promotion of autonomous

learning nowadays.

Peer correction occurs when one learner corrects another one. Its most important advantages are that both learners are

involved in face-to-face interaction; the teacher obtains information about

learners’ current abilities; learners co-operate in language learning and

become less teacher-dependent; peer correction does not make errors a public

affair, which protects the learners’ egos and increases their

self-confidence.

Teacher correction occurs, of course, when the person to correct the

errors is the teacher. He or she knows the problem and the solution, and can

define and put things simply so that the learner can understand the error.

As shown in the previous pages, CF is a very complex

phenomenon in EFL which has its own peculiarities that distinguish it from ESL

contexts. It is not only that the classroom is the setting where learners

mainly receive language input, but also where they receive their provision of

CF. With this limitation, thinking about CF and its role in language learning

in this particular context becomes a relevant issue. Practicing CF in EFL

settings is therefore a complex task in which many factors meet and intertwine.

Teachers have to ask themselves: Why to include CF? How to provide CF? What to

correct? How much CF and how frequently? Who is to correct? And then make

decisions. Additionally, teachers have also to be concerned with the individual

differences. This is something that will be discussed in the findings in the

next section.

Method

This is a descriptive study conducted at a Mexican

university located in the southeast region of the country. This university

offers English as Foreign Language (EFL) courses from beginners to advanced

level to all undergraduate students. However, they only have to cover, as a

graduation requirement, four levels of English (from Beginner to Intermediate).

The population of students taking EFL courses totals 600 every term,

approximately, and there are about 40 instructors teaching these courses.

For this study, a semi-structured interview and a questionnaire

were used to collect the data. Five language instructors, with ages from 25 to

60, were interviewed. Their teaching experience ranged from 4 to 20 years. The

interviews were recorded and analyzed considering variables such as types of

errors, the CF provider, frequency of correction, CF techniques, perceptions of students’ attitudes, training, and

perceptions about CF.

A questionnaire was designed and distributed among 40

instructors. Unfortunately, only 15 gave us back the questionnaire. The instructors

were teaching courses from introductory to intermediate levels at that time.

The questionnaire consisted of five sections intended to obtain data about

those instructors’ ideas on CF and its practice in the classroom;

perceptions about their learners’ reactions and attitudes toward CF;

attention paid to the different language levels (i.e. phonetics phonology,

syntax, morphology, semantics, and pragmatics); the different strategies used

to provide oral CF and its frequency of use; and instructors’ perceptions

on the strategies most preferred by their students.

To analyze the data, descriptive statistics were used

with SPSS v. 18 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences), and a

qualitative analysis of the variables was conducted and interpreted by both

researchers.

Findings and

Discussion

The Role and

Importance of Corrective Feedback in the Classroom

From the questionnaires there is a strong tendency

(80%) to agree on the need to correct learners so that they gain fluency and

accuracy. This is concurrent with the idea that CF has a positive impact on

language learning in which 87.7% of the instructors agreed. However, 3 out of

15 teachers believe that CF does not play a relevant role in the acquisition of

fluency and accuracy. In the interviews, 4 out of 5 instructors agreed with the

need to provide oral CF in the classroom, but it seems they do not believe in

the benefits of CF, or the impact it can have on the learners. They consider CF

to be only necessary to develop accuracy.

Overall, these instructors have positive beliefs and

attitudes toward oral CF, as they consider it necessary for language learning.

Nonetheless, in the interviews most of the teachers associate CF to focus on

form (limited to accuracy). It seems that they favor the focus on meaning

instruction (and fluency), and therefore, they cannot accept CF completely.

This lack of total acceptance may have to do with their academic profile and

teaching experience; their previous knowledge and education.

Effects on

Learners: Reactions, Emotions and Feelings

13.3% consider that CF inhibits students’

participation, 60% partially agreed with this statement and 20% disagreed.

These varied answers probably have to do with the consideration of other

variables that can influence this outcome. If teachers consider, for example,

that individual correction affects more than group correction, and it does

prevent further participation, then that is why they either agreed or partially

agreed. They may also have thought that the amount of CF could be another

variable affecting participation. These results coincided with those of the

interviews, in which instructors mentioned that it was important to get to know

their students very well in order to know if CF could be used or not with some

students. They said that learners had different attitudes toward CF and

teachers should be aware of this and decide whether or not to consider it for

the provision of CF. 3 out of 5 teachers said that at the beginning of their

courses they asked their students if they wanted to be corrected. This leads

one to think that teachers perceive CF as an activity with many intricate

variables to control, and if this is not done tactfully, then it may be

detrimental to class participation.

33.4% consider frequent CF as a cause of frustration

or demotivation; 46.7% partially agreed, and 20% disagreed. Again, it seems

that teachers think of CF as a potential cause of these emotions or feelings if

some other issues (such as personal traits) are not controlled or considered

for the provision of CF. This was also manifested in the interviews where

instructors expressed that CF could damage the learners’ feelings and the

process of learning if used very frequently and regardless of the personality

or emotions of the students.

A contradiction, however, was identified in the

results. When asked if shyness or low motivation should be factors to consider

in the provision of CF, 66.7% did not think so, and the rest partially agreed

with this statement. This complements the question of whether correction should

be used only with more open/receptive learners. 60% of the instructors

disagreed on correcting only this type of student; 13.3% partially agreed and

26.7% agreed. There is inconsistency by some in conceiving error correction as

an inhibitor of participation or a factor of de-motivation. Yet they think that

shyness and low motivation should not prevent CF from taking place in the

classroom. In the interviews, teachers expressed being very concerned with

learners’ personality traits, preferences, and attitudes. It appears then

that there is not complete agreement in this respect.

Teachers in general (80%) perceive that learners do

not get angry or feel bothered when provided with oral CF. In the interviews they agreed that anger

and annoyance are not emotions manifested by students in their classroom, but

that anxiety, shyness, and introversion were thought of as factors to consider

for CF provision.

A paramount reaction to CF is the learners’

uptake and repair, that is, what do they do with this CF? Do they correct? 60%

agreed that learners do repair their utterances frequently and always; 33.3%

said learners do it sometimes, and 6.7% agreed that learners never correct

their errors. In the interviews, 3 out of 5 instructors agreed that their students

repair; 2 said that learners do it sometimes. Therefore, in general, there is

this perception that repair takes place in their classroom with regular

frequency. This belief can actually be one of the factors causing some negative

or cautious attitude toward CF. Why

should teachers bother to provide CF if students do not respond to it? If CF is

not helping, why include it in the teaching practice?

The Role of

Learners’ Proficiency in CF

60% of instructors in this institution consider that

the use of certain CF strategies depends on the learners’ proficiency.

Similar results were obtained through the interviews (3 out of 5 teachers).

They said that body language, for example, could be more exploited with

beginners, whereas meta-linguistic explanations should be used more with

advanced students who have better proficiency in the L2. They also suggested

that peer correction is more suitable for advanced students, but not for

beginners because they are not used to this type of strategy and they do not

trust their classmates for this endeavor. 20%, however, do not think that

proficiency in the target language influences the choice of one or another

strategy, and 20% partially agreed.

These perceptions could be based on other factors

besides proficiency level. Typically students at this institution begin to

learn English during their first year of college, and as they progress in the

English courses (and therefore gain proficiency), they also get to know their

classmates better since they are often placed in the same classroom and have

the same schedule. So, while beginners have sometimes complete strangers as

classmates, in other higher level English courses, students are acquainted with

many of their classmates. This ensures a more trusting environment. In some

classrooms the instructor is the only newcomer.

It is also interesting to examine these results if we

consider that some students are not familiar with all CF strategies or with

meta-language. Two teachers mentioned in the interview that beginners have no

idea of what a verb is, an adjective or a pronoun.

Consequently, using meta-linguistic feedback is unthinkable at the beginning

levels. However, advanced learners do know these terms and are then able to

understand the explanations, and repair. The same occurs with some students who

have not experienced the different CF strategies, which usually occurs in the

first English courses.

When to Correct

Regarding the distinction between immediate or delayed

CF, 40% agreed that teachers should provide CF just immediately after the

learner has made an error, but without interruption; and 53% partially agreed

with this statement. This partial agreement is probably rooted in the purpose

teachers have with CF e.g. if the teachers’ focus is on accuracy, then they

will probably engage in CF immediately; or if it is fluency, they can delay

correction.

Most professors (60%) prefer to provide the whole

class with CF at the end of the class time. 33% partially agreed with this

practice. This trend can be understood as teachers’ concern with

learners’ feelings and emotions and their fear of interrupting and

inhibiting participation. The above interpretation (accuracy and fluency

distinction) can apply to this result as well. This preference on behalf of the

instructors, however, differs with regard to “what should be done”.

Concerning the statement, “Not only general errors made by the whole

class should be corrected, but also individual errors”, 73% agreed with

it. In the interviews, most of the teachers showed a preference for CF to be

provided for the whole class.

Types of Errors to

Correct

With regard to correcting only errors that interfere

with meaning and with getting the message across, 46% partially agreed and 46%

disagreed. It seems then that there is a tendency not to favor this practice in

the classroom, or that this may depend on the activities involved and on the

focus (meaning vs. form).

There is also a clear tendency on behalf of the

instructors to direct CF toward morphosyntactic

errors (86.7%), followed by pronunciation (73.3%), lexicon (66.7%) and

pragmatics (53.3%). Interestingly,

as percentages get lower, more diverse answers to the amount of attention are

observed; that is lexicon and pragmatics, for example, had answers such as

“some” and “little”, respectively, whereas morphosyntax and pronunciation got “a lot” by

most teachers. These findings are similar to the answers provided by the

teachers in the interview, in which most of them (4 out of 5) emphasized they

indeed corrected pronunciation and morphosyntactic

errors. None mentioned pragmatic errors. Unfocused correction was manifested

through the different examples used to show the type of corrective feedback in

their classrooms.

These findings (pronunciation and morphosyntactic

errors as main targets) suggest that these instructors pay more attention to

language structures rather than meanings when providing CF. They see CF as a

way to prevent or correct structure errors. On the contrary, they care less

about semantic or pragmatic meanings. This does not correspond to a focus on

meaning instruction.

Who Corrects

In the questionnaire, 86.7% consider that the teacher

is not the only one who can and must correct errors. This coincides with 73.3%

in agreement with the statement that the learners should engage in

self-correction with the instructor’s help. Although there seems to be a

positive attitude toward self-correction, their perceptions about the

effectiveness of CF considering the corrector are not consistent among all the

teachers. 40% agreed that self-correction is more effective than

teachers’ CF, and 33% partially agreed. Thus, other variables are

apparently seen as intervening in this effectiveness.

Peer correction, on the other hand, is not perceived

as a positive activity in the classroom by most teachers (86.7%). The rest

partially agreed with having peer correction in the classroom, but none agreed

on this strategy as something positive. When asked about the effectiveness of

teachers’ correction and peer correction, 53.4% do not consider the

former to be more effective than the latter; the rest agreed and partially

agreed with this statement.

All interviewees agreed that the teacher is the

authority for providing CF in the classroom. The instructors do not think that

peers are good at correcting their classmates; actually, they said that

sometimes peer correction can be harmful for the relationships among students.

Generally speaking, teachers seem to favor more teachers’ CF, followed by

self-CF and then by peer CF. They perceive the former to be the most effective

as well. This is probably a result of the traditional and paternalistic

education we have had in Mexico for many years. Learners’ autonomy has

been included in the schools’ curricula very recently,

and teachers and students are still trying to integrate this into the

classrooms, but it has not been easy.

CF Strategies and

Their Frequency of Use

The favored strategy was to ask for clarification or

confirmation, which was reported to be used always and most frequently by 86.6%

of the teachers, although the remaining 13.4% report periodic use. Gestures and

mimicry, as well as recasting, were favored next by 80% of the teachers, who

reported using them always, and the remaining 20% periodically. 67.7% of

teachers emphasize the error so that the learner makes the correction. They use

this strategy always and frequently; 20% rarely use this strategy. This

emphasis is made mainly with a change in intonation when uttering the erroneous

part, or putting the error into a question. (For example, a student says: Where

did you went last weekend? Teacher replies: Went?).

Most teachers in the interview pointed out that this was one of the main

strategies they used and they thought it worked very well with students.

Regarding peer correction, 60% reported using it

rarely and 20% only sometimes. This supports what was found regarding who

carries out the CF in the classroom as mentioned above. Three interviewees

argued that they do not use peer correction very frequently because they thought

that this type of feedback could create negative attitudes among the students

toward their classmates; many times, they claimed, the “corrector”

is seen as superior or a more knowledgeable person than the rest, and this can

create a hostile environment which prevents proper camaraderie among students.

Finally, concerning grammatical explanation as a CF

strategy, results from the questionnaires show that 46.6% always and frequently

provide grammatical explanations; 33% do it sometimes, and 6.7% rarely. In the

interviews some teachers (3 out of 5) also manifested some aversion to this

strategy, mainly the youngest instructors who insisted that other strategies

could be used instead with more positive outcomes. These answers suggest that

teachers do not seem to favor explicit correction.

In sum, these trends in strategies used show a higher

frequency and preference toward indirect and implicit CF (clarification

requests, confirmation checks, gestures), followed by direct and explicit

strategies (emphasizing the error and grammatical explanations). Peer

correction seems not to be promoted by teachers, but self-correction instead.

In the interviews, similar answers were reported, although self-correction was

the least promoted by the professors, who highlighted the lack of language

awareness on behalf of students correcting their errors.

Learners’

Preferences According to Teachers

70% think that their students prefer a teacher’s

CF rather than a peer’s. This concurs with their perception (84.6%) that

students would prefer that their instructors do not ask a classmate to help

with their corrections. All interviewees agreed that students prefer

teachers’ feedback rather than their classmates’. They added this

was rooted in the following perceptions: That the teacher is the authority in

the class and an expert and their classmates do not seem to be very reliable.

As such, peers do not rely on their classmates’ CF. Also, peer correction

could cause a negative impact on the students’ relationships because, for

example, a student could be corrected by someone he does not like and this

could cause some kind of unconstructive attitudes or undesirable reactions.

As to the time when CF is provided, 76.9% consider

that students prefer for the instructor to provide CF immediately just after

the error has been made. The same percentage believes that students favor group

correction rather than individual CF.

This seems contradictory because if learners wanted to be corrected

immediately after the error, this would imply individual correction. However,

in the interviews teachers mentioned that learners prefer both (depending on

the type of error, or in order to have some variety in strategies). 53.8%

agreed with their perception that students like personal and individual CF.

Regarding the students’ favorite oral CF

strategies, according to the teachers’ perceptions, 61.5% suggested

recasting as number one, followed by grammatical explanations, provision of

further examples (60%), gestures, and finally clarification requests (53.8%).

Although implicit strategies seem to be the most preferred, grammatical

explanations came in second place. This finding, interestingly, does not match

the teachers’ practice of this strategy since they reported lower use of

this one in particular and a clear tendency to favor indirect strategies. A

possible interpretation of this is that teachers probably reported what they

believed or thought as regards how oral CF should be provided, but not how they

actually provide it.

Conclusions

and Suggestions

In general, teachers at this institution have a

positive perception of oral corrective feedback. However, they need to know

more about its effects and role in interlanguage

development because they look at CF only as a technique to improve accuracy in

the language, particularly in pronunciation and morphosyntax.

Some teachers actually consider CF as optional (mainly individual CF) because

they are very concerned with students’ feelings and emotions. In this

regard, these instructors in particular have such a respect for the individual

differences such as personality, attitudes, motivation, and beliefs, that this

affects—sometimes positively and other times negatively—their

practice with regard to oral CF.

Unfocused oral CF is predominant in the

instructors’ practices and this situation may need to be reconsidered as

it probably inhibits the learners’ noticing their errors and subsequent

pursuit of repair. With many aspects covered at the same time, students might

not engage in as much correction as desired. Teachers should make it clear to

their students what they need to correct and pay more attention to it so that

repair does indeed occur.

With regard to the use of strategies, the implicit

ones are more favored by this group of teachers. Teachers should know the

effectiveness of both explicit and implicit strategies and choose the ones

proven to be more effective. As a matter of variability, many possible

strategies should be exploited in the classroom.

For the instructors, the most suitable person to

provide CF is the teacher, followed by the learner doing self-correction; peer

correction is the least favored. However, fostering autonomous learning is a

paramount task in the teachers’ agenda as is collaborative learning.

Teachers should be aware of the advantages that self and peer correction have,

as they can raise or increase language awareness and

help learners to test hypotheses in the target language.

In brief, this research in the Mexican context

provides, in general, evidence of similar problems found in previous studies (Allwright, 1975; Chaudron, 1977;

Long, 1977; Lyster & Ranta,

1997; Lyster & Mori, 2006): inconsistency;

ambiguity of teachers’ corrections; random and unsystematic feedback on

errors by teachers; acceptance of errors for fear of interrupting the

communication; and a wide range of learner error types addressed as corrective

feedback. The first step then is, as language teachers, to learn more about CF

and to share it with the learners; to manage individual differences in a way

that they do not interfere with the language learning; to put into practice new

and more effective strategies; to organize and systematize corrective feedback;

and to set clear and feasible goals in this respect.

1 S= student; T= teacher. Samples are of our own.

References

Allwright, R. L. (1975). Problems in the study of the language

teacher’s treatment of error. In M. K. Burt & H. D. Dulay (Eds.), New directions in

second language learning, teaching, and bilingual education. Selected

papers from the Ninth Annual TESOL Convention.

Washington, D.C: TESOL.

Chaudron, C. (1977). A descriptive model of discourse in the

corrective treatment of learners’ errors. Language Learning, 27, 29-46.

Ellis, R.

(2001). Investigating form-focused instruction. Language Learning, 51(1), 1-46.

Ellis, R., Loewen,

S., & Erlam, R. (2006). Implicit and explicit corrective feedback and the

acquisition of L2 grammar. Studies of Second Language Acquisition, 28,

339-368.

Han, Z. H.

(2008). Error correction: Towards a

differential approach. Paper presented at The Fourth QCC Colloquium on

Second Language Acquisition. New York, NY. Retrieved from http://www.tc.columbia.edu/academics/?facid=zhh2

Krashen, S. D. (1982). Principles and

practice in second language acquisition. New York, NY: Pergamon

Institute of English.

Long, M.

(1977). Teacher feedback on learner error: Mapping cognitions. In H. Brown, C. Yorio & R. Crymes (Eds.), TESOL`77. Teaching and learning English as a

second language: Trends in research and practice (pp. 278-294). Washington

D.C.: TESOL.

Loewen, S., Li,

S., Fei, F., Thomson, A., Nakatsukasa,

K., Ahn, S., & Chen, X. (2009). L2 learners’ beliefs about grammar instruction and error

correction. The Modern Language

Journal, 93(1), 91-104.

Lyster, R., & Mori, H. (2006). Interactional feedback and

instructional counterbalance. Studies

in Second Language Acquisition, 28, 269-300.

Lyster, R., & Ranta, L.

(1997). Corrective feedback and learner uptake. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 19, 37-66.

Mackey, A., Gass S., &

McDonough, K. (2000). How do learners

perceive interactional

feedback? Studies in Second

Language Acquisition, 2, 471-497.

Sheen, Y.

(2011). Corrective

feedback, individual differences and second language learning.

Dordrecht: Springer.

Yao, S.

(2000). Focus on form in the foreign

language classroom: EFL college learners’ attitudes toward error

correction. Buffalo: State University of New York at Buffalo.

Yoshida, R.

(2008). Teachers’ choice and learners’ preference

of corrective feedback types. Language

Awareness, 17(1), 78-93.

About the

Authors

Edith

Hernández Méndez holds a PhD

in Hispanic Linguistics from Ohio State University. Full time

professor at Universidad de Quintana Roo and member

of the National System of Researchers in Mexico. Research interests:

language acquisition, language learning and teaching, and sociolinguistics.

María del Rosario Reyes Cruz holds a PhD in International Education

from Universidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas. Full time professor at Universidad de Quintana Roo and member of the National System of Researchers in

Mexico. Research interests: pedagogical beliefs,

epistemological beliefs, beliefs about language learning, and educational

technology.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Visitas a la página del resumen del artículo

Descargas

Licencia

Los contenidos de la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development son de acceso abierto y los cubre la Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivar 4.0 Internacional. Se autoriza copiar, redistribuir el material en cualquier medio o formato, siempre y cuando se conceda el crédito a los autores de los textos y a la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development como fuente de primera publicación. No se permite el uso comercial de copia o distribución de contenidos, así como tampoco la adaptación, derivación o transformación alguna de estos sin la autorización previa de los autores y de la Editora de la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.

Los autores conservan la propiedad intelectual de sus manuscritos con la siguiente restricción: el derecho de primera publicación es otorgado a la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.