A Model for the Strategic Use of Metacognitive Reading Comprehension Strategies

Uso estratégico de metodologías meta-cognitivas de compresión lectora

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n2.58826Palabras clave:

English as a foreign language, metacognition, reading comprehension, reading strategies (en)comprensión de lectura, estrategias de lectura, inglés como lengua extranjera, meta-cognición (es)

Descargas

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n2.58826

A Model for the Strategic Use of Metacognitive Reading Comprehension Strategies

Uso estratégico de metodologías meta-cognitivas de compresión lectora

Juan David Gómez González*

Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia

This article was received on July 2, 2016, and accepted on January 14, 2017.

This article represents the final results of the research project, “Metacognitive strategies and second language reading comprehension” (code number: 2015-2922), which is sponsored by the Coordinación de Proyectos de Investigación, Instituto de Filosofía and the Universidad de Antioquia.

How to cite this article (APA, 6th ed.):

Gómez González, J. D. (2017). A model for the strategic use of metacognitive reading comprehension strategies. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 19(2), 187-201. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n2.58826.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This paper describes an approach to developing intermediate level reading proficiency through a strategic and iterative use of a discreet set of tasks that combine some of the more common metacognitive theories and strategies that have been published in the past thirty years. The case for incorporating this composite approach into reading comprehension classes begins with an explanation of its benefits and the context in which it came to be; its relationship to theoretical discourse in the field; a description of its three main components: textual indicators, strategy instruction, and content learning; and concludes by presenting a model for implementing the approach that integrates these three components.

Key words: English as a foreign language, metacognition, reading comprehension, reading strategies.

La propuesta que se presenta apunta al desarrollo de la comprensión lectora en un nivel intermedio mediante el uso estratégico e iterativo de tareas específicas. La argumentación a favor de incorporar este acercamiento compuesto en clases de comprensión lectora empieza con una explicación de sus ventajas, el contexto en el cual llegó a ser y la relación que luego se estableció con el discurso teórico del campo. Posteriormente, se detallan sus tres elementos principales: indicadores textuales, enseñanza de estrategias y aprendizaje de contenido. Se concluye con un modelo pedagógico para la implementación del acercamiento que hace uso de los tres elementos constitutivos de la propuesta.

Palabras clave: comprensión de lectura, estrategias de lectura, inglés como lengua extranjera, meta-cognición.

Introduction

Preparing university students in non-English speaking countries to use English language texts has been a pressing concern for policy makers, administrators, and professors for the past twenty years (Crystal, 1999; Seargeant & Erling, 2011). For most of the past decade, the Colombian Ministry of Education has addressed this issue by taking steps toward the implementation of a national bilingual program (Programa Nacional de Bilingüismo 2004-2019). The ministry justifies this policy by stating that it considers bilingualism to be essential in a globalized world and an important element in enriching the lives of its citizens, increasing their competitiveness and contributing to the overall development of the country (Ministerio de Educación Nacional, 2005).

The proposal presented here came to be as a response to the particular needs of students at Universidad de Antioquia (UdeA), one of the largest public universities in Colombia. These were English as foreign language (EFL) students with limited English proficiency (LEP) that needed access to English language texts, primarily in their field of study, but also for their overall development as professionals. This article makes the case for an approach that addressed their reading comprehension needs because those needs are common enough that the proposals found here may be of value to a great many.

Rationale

In 2015, 2,063 undergraduates at Universidad de Antioquia (UdeA), one of the largest public universities in Colombia, took an English reading competency exam. Fifty-six percent of them failed the exam. Students from the engineering department, the largest on a campus of 30 thousand-plus students and the beneficiaries of six levels of mandatory EFL courses fared no better than the greater population. In the first semester of that same year, 57% of those students who took the exam failed (Informe de Gestión, 2016, see Appendix A). These statistics were representative of what I observed when I began to teach reading comprehension at this same university. The numbers also make clear the need that public institutions such as UdeA have for practical, user-friendly tools that can be used readily by the underpaid and often underprepared adjunct instructors who in most departments are responsible for more than 60% of the undergraduate teaching load.

Upon being hired to teach three levels of reading comprehension to philosophy students enrolled in a teacher preparation program, I was asked to mitigate the student’s aversion when faced with academic texts in English, as they often experienced when complementary bibliography was called for in their content courses. I addressed this challenge first by performing a detailed needs assessment survey of all three levels and found the following: of the 72 students surveyed, 59 interacted with texts in English (academic or otherwise) less than three times per month, eight students less than five times per month and five students more than five times per month. Most, (54 students) thought it important to increase the frequency with which they read in English. The primary reason given by this group of 54 students as to why they did not read more often in English consisted of a low opinion of their ability to make use of the texts that they encountered. This low opinion of their proficiency in reading was manifested in comments such as “there are a lot of words that I still don’t know” and “I have a lot of trouble translating the important sentences in the text.”1

My field notes showed that when faced with short expository texts (averaging 190 words) that were accompanied by multiple choice questions, nearly all students read intensively, word for word from left to right until they encountered an unknown word, at which point they reached for the dictionary apps on their smart phones. When I suggested skipping some of the unknown words and attacking the text in an asymmetrical fashion, some acquiesced, albeit reluctantly. Once I moved on to assist other students however, they quickly returned to scrutinizing the text one phoneme at a time.

I proceeded to identify the available tools offered in articles and textbooks and culled a selected group of those that through trial and error showed themselves to be the most promising. My plan was to use them as rhetorical tools that would help me to persuade my classes that they would be able to achieve much more than they believed that they could if they were willing to rethink the manner in which they interacted with English language texts. The result of this three-and-a-half-year endeavor is the strategic iterative reading comprehension approach (SIRCA).2

The term reading comprehension has a very limited scope in our classes, one that I believe to be shared by a broad spectrum of EFL students. This limited scope means that we focus on improving our ability to make use of academic texts for our professional and personal needs. The process that allows us to achieve this is founded on and guided exclusively by the purpose, the goal to be achieved and not by the tools that we use (or other language learning goals). It is a process designed to give students clear and explicit orientation as to when and how to use strategies. In this sense, this article takes a different tack from those that evaluate and classify strategies but stops short of engaging explicit prescriptive ends. In response to the abundance of descriptive models found in the field, SIRCA encourages a move from a transmission model of teaching toward an active transactional model that is based on explicit student-centered learning goals. The explicit goals that concern us can be located within the dimensions of task knowledge, task purpose, and task demands (Rubin, 1994). SIRCA works to achieve those goals by answering the call for explicit and integrated strategy instruction (Graham & Harris, 2000; Shen, 2003) and by emphasizing awareness development through teacher modeling, practice, and self-evaluation (Chamot, Barnhardt, El-Dinary, & Robbins, 1999; Harris, 2003).

SIRCA integrates theories of learning processes, instructional procedures, and content instruction but is not a method for English language instruction. What it does is promote student motivation by creating a greater sense of autonomy and a clear sense of purpose; a sense of where the reader is headed, why, and how to arrive there. It is targeted at a specific but growing section within the EFL community; students for whom achieving an intermediate or advanced level of reading comprehension proficiency is a valuable objective but who do not have the resources to do so. The use of traditional methods like ESP (English for specific purposes) and EAP (English for academic purposes) can provide students with a basic level of competency in the four language skills but, the limited time available for these courses often results in a level of reading proficiency that falls short of the demands found in a globalized academic environment.

SIRCA focuses on two of these demands: (1) the ability to perform successfully in timed multiple choice reading comprehension exams and (2) the ability to write an “abstract” or summary based on a structural/semantic map (S-map) of an academic text in English. Both of these are indispensable skills for an undergraduate in any major to have. The need for exam skills is self-explanatory. By being able to represent the purpose and structure of a text in a conceptual map and then in prose, the student will have an understanding of what the text does and how it does it. This, in turn, will allow the student to use the text for the purposes of research presentations, answering questions, and critical review.

Additionally, the skills acquired are directly transferable to the student’s native language (L1). This means that along with having access to English language texts in their field, the student will improve the speed and efficacy with which he or she reads overall, thus the impact of using this approach can be said to extend beyond the EFL class and beyond the academic sphere into the personal and professional interests of the students who use it. They achieve this in part by employing those practices that define effective readers, namely, knowledge of syntax and structure, use of contextual clues, identifying key words, identifying the main idea, predicting, and confirming.

Theoretical Framework

Sources Integrated Into SIRCA

SIRCA is an integrative effort that recycles many of the theoretical models and findings in the area of metacognitive reading strategies already available and organizes them into a systematic and strategic approach to reading comprehension. In a field long affected by entropic tendencies that often make cross study comparisons nearly impossible (Chamot, 2004), novelty is not what is most needed. It may be more beneficial to offer synthesis and prescriptive proposals that make practical use of the wealth of available theoretical models and tools.

SIRCA borrows from a variety of existing approaches such as EAP because students are initially engaged in using English texts to serve their academic needs. It can be thought of as a Genre based approach, because genre analysis (in general) focuses on the structural organization of texts; an identification of lexico-grammatical features, moves, and strategies with a mind to understanding how these are organized to accomplish the communicative (or rhetorical) purpose of the text (Osman, 2004). Through SIRCA, students are able to focus on the patterns and organizational structure of expository and persuasive texts as well as to become familiar with the textual regularities of these genres. It also adapts some of the central tenets of task based strategies (TBS) because all activities are guided by one clearly defined task; to extract the central purpose and the general structure of the academic text either as a platform from which to answer multiple choice questions on standardized proficiency exams or as a means toward filtering through primary and secondary source texts in the practice of research.

The benefits of incorporating explicit reading goals result from the fact that reading strategies are influenced by the specific goals that readers seek to achieve and it is only by defining, committing, and returning to these goals throughout the reading activity that strategies become useful and powerful tools for students rather than cumbersome and taxing obligations placed on an already busy cognitive system. This is important to what is proposed here because the learning theory behind SIRCA is the understanding that strategic readers are more effective readers and that these can be defined as individuals who understand the goals of the reading activity, have a broad range of strategies to choose from, are adept at using them in combination, and employ comprehension monitoring (Grabe & Stoller, 2001). Good readers are selectively attentive, attempt to integrate across the text, and identify categories; they are able to appropriate and coordinate strategies opportunistically (Pressley & Afflerbach, 1995). In the last three decades, studies on reading comprehension strategy instruction have concluded that the combination of explicit goals and strategy use help readers to be more effective and efficient. (Koda, 2004; Lenski & Nierstheimer, 2002; Palincsar & Brown, 1984; Rosenshine & Meister, 1994; Song, 1998).

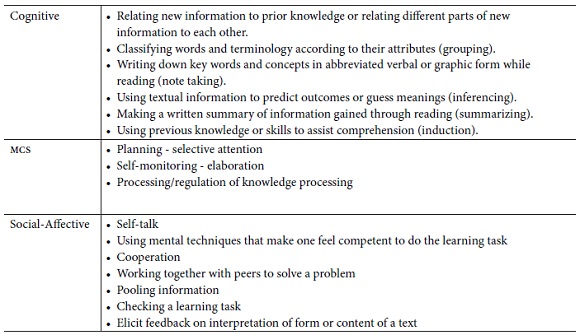

The strategy instruction component presented here follows Anderson’s (language theory) model of language acquisition (1981, 1985) insofar as it is a cognitive model that helps us to understand reading comprehension as a complex cognitive skill that can be broken down into a cognitive stage, during which there is conscious, rule-based learning, an associative stage, in which errors diminish and the reading strategies are executed more fluently, as well as an autonomous stage during which parts of the learned strategies become unconsciously performed skills that are incorporated into the reader’s automatic skill set (see Appendix B).3

The explicit instruction model promoted by Graham and Harris (2000) and Pressley (2000) has also been adapted into the SIRCA model in that the content, rhetorical, lexical, and syntactical knowledge specific to expository and persuasive texts is the “declarative knowledge” component. These are taught in tandem with the reading strategy component or “procedural knowledge”, which consists of a recursive task-based model that is repeated with a broad variety of texts until these strategies have been assimilated and become skills.

Metacognitive Reading Strategies

Metacognitive reading strategies (MCRs) are central components of this approach because the evidence we have about their effectiveness is considerable. Years of extensive research have shown us that they enable LEP students to improve their reading proficiency (Ikeda & Takeuchi, 2003; Kazemi, Hosseini, & Kohandani, 2013; Wilson & Bai, 2010; Zhou & Zhao, 2014). The use of MCRs here is based on four main propositions: (1) Students who can establish cognitive links that relate newly acquired information with previous knowledge are more effective readers than those who are not mentally active and resort to rote memorization (Barnett, 1988; Waxman & Padron, 1987). (2) Strategies can be learned. Those who are taught MCRs and provided with ample time to practice them will be more effective readers than those who have no experience with them or have not had explicit instruction as to their nature and use (Cotterall, 1990; Paris, Lipson, & Wixon, 1983). (3) MCRs transfer between L2 and L1 (Rhoder, 2002; Salataci & Akyel, 2002). (4) Improved reading comprehension in LEP students is more effective through direct instruction of MCRs than with traditional language processing methods of reading instruction (Carrell, 1998). The process of explicit reading strategy implementation begins by making learners conscious of covert processes, knowledge, and skills that they can learn to control so that they can evolve into more effective readers (Cambourne, 1999).

Components to the Proposed Approach

Textual Indicators

The language development component used in our classes includes a core list of linguistic or discourse markers, prefixes, suffixes, roots, and those verbs and nouns that are more likely to appear in academic texts (in the social sciences). Nouns like researchers, findings, studies, and verbs like argue, concede, imply are more useful to us than wander, revel, and mingle because they appear more often in the kinds of texts that concern us.4 The discourse markers and their functions: enumerative, additive, conclusive, resultative, and contrastive, etc., are presented so that the individual terms are understood as performing a specific function in a text; words like but, conversely, instead are not learned as independent meaning units but as part of a category. In this case, a category of words that contrasts what is to follow with what preceded them. The purpose behind teaching the roots, prefixes, and suffixes is akin to why we learn about discourse markers. Both provide students with an alternative means to decipher meaning where their vocabulary and syntactical knowledge may be insufficient. Research has demonstrated high levels of correlations between discourse marker knowledge and improved reading comprehension proficiency (Khatib & Safari, 2011).

Strategy Instruction

The acquisition of specialized vocabulary and syntax is important to the course only insofar as the manner in which these complement our use of strategies and allow us to improve our proficiency in working with academic texts in English. When using these strategies, the expression “working with texts” has a meaning for us that is slightly different from what is understood as decoding or deciphering texts, wholly or partially. What “working with texts” means to us is that we work to identify what the text does, whether it is expository or persuasive and how it does what it does. These are the goals of the class and of the strategies that we use.

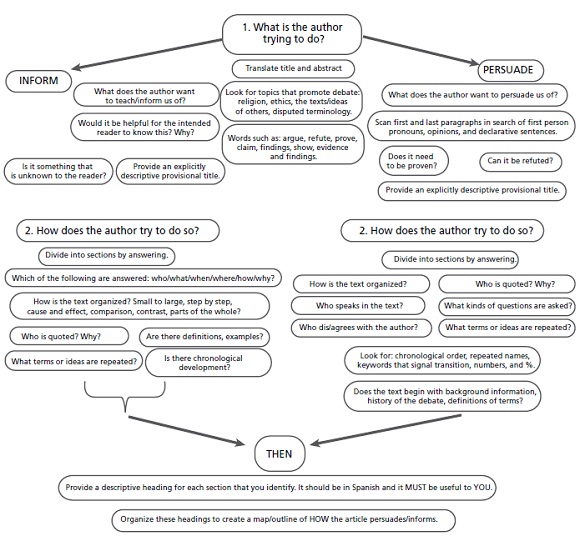

The strategy instruction component is expressed in the SIRCA guide map (G-map, see Appendix C). The G-map is composed of questions that the reader uses to direct his or her reading. Each question is considered separately and if no answer is found, the reader then moves to the following question in that section. Some of these sections require that the reader return to certain sections of the text, each time with a different question in hand; herein lies one of the iterative characteristics of this approach.

The recursive task based model relies heavily on the well-established practice of “scanning” and limits the use of the “skimming” component. By using the G-map, the student will always have specific questions in mind; he or she will always be scanning; looking for the answers to a question. The logic behind this is that skimming, or looking for the general idea, the main points, and the general structure is a task for which LEPs are seldom equipped. By providing a clear and achievable goal, finding answers to questions and using the answers to develop the S-map, the G-map limits the sense of impotence that students feel when we ask them to “decode the important parts of the text” or “identify the relevant information in it”. Instructions of this sort can cause confusion and a consequent lack of motivation because LEPs often do not know how to distinguish relevant from irrelevant information. One exception to this is LEP students who have been trained in basic test taking techniques. These students will, for the most part, be more effective at assimilating the G-map format because they have learned a reading approach that is goal oriented. SIRCA’s G-map consists of a set of questions tailored to guiding students in their approach to academic texts.

Initially, students are asked to follow the steps presented in the G-map in sequential fashion. As they progress through the steps they find tips and complementary questions that help them to answer the two primary questions: what and how (here we find a second iterative characteristic of the approach). Once they have addressed one of the tips presented in the “How” section of the G-map, scanning for keywords that will help them to determine if “small to large” is the organizing principle behind the structure of the text, for example (and if the search is unsuccessful), they return and tackle the next tip/question, that is, scan for clues such as dates and other temporal indicators to see if the text is organized sequentially.

At first the going is slow, but only while students assimilate the types of clues that they must look for to answer the “what and how” questions and are better able to resist the urge to give every word equal importance. Developing these abilities requires the use of metacognitive strategies like planning, selective attention, and self-monitoring. Once students become accustomed to attacking the text; to actively searching through it with the sole purpose of answering the questions in the G-map, measurable progress in their reading proficiency will follow. There is a significant time investment to be made at the initial levels because students will be asked to see the familiar (a text) in an unfamiliar way; as a compound that needs to be broken down into its elements. Effective implementation of strategy instruction will reduce the length of time invested but the application of MCRs as suggested here, or elsewhere, is not a quick fix. It is a difficult, time consuming, though effective way towards creating better readers (Farell, 2001).

The activities spelled out by the G-map take on form in the S-map. The semantic/structural map (Carrell, 1998) is a graphic display of information within categories that have explicit relationships to a central concept (Johnson, in the foreword to Heimlich & Pittelman, 1986). The S-map is both semantic and structural in that it illustrates what the text is trying to achieve, present in the title given to the S-map, and the sections that explain how it tries to do so.

Let us say that our what question, what the text does, leads us to conclude that the text informs us that our earliest ancestors were hunter gatherers; this then becomes the provisional title of our S-map, abbreviated as “Ancestors were H.G.” The following question, how the text manages to carry this out, will guide us toward dividing the text into sections. We would carry this out by placing a descriptive heading above each section and then using these headings to develop the S-map. Finding the answer to the questions in the G-map, and creating an S-map with them will require cognitive skills such as grouping, note taking, summarizing, induction, and inferencing.

In the process of integrating the section headings (the How the text tries to achieve its goal) with the provisional heading of the S-map (the What the text tries to achieve), one sees that the metacognitive strategies of self-monitoring and elaboration are key. The former, because it ensures active engagement with the defined reading goals and the latter, because it is the primary means through which the reader may recall prior knowledge, consciously relate it with what he or she is presently learning and then integrate this to the semantic structure that is their S-map. In the classroom, these strategies are taught, modeled, and practiced by way of social affective strategies such as cooperation and self-talk. The final version of the S-map is a structural and semantic rendering of the text. It shows what the author intends to accomplish and how the parts of the text are organized so as to achieve this goal. Because of the great variety of rhetorical conventions, mastering the development of an S-map with persuasive texts will require more practice than with informative or expository texts.

The S-map gives students the information that they need to achieve four of the most common academic reading goals for university students, among them “reading to research, answer questions, summarize, and reading for critical review” (O’Hara, 1996, p. 7). The last goal is made possible because the S-map gives the student information about whether the parts do in fact accomplish the purpose that the author set out to achieve, whether they may do so if organized in a different manner, or to what extent some of them fail to do so altogether. For example, if a student is given an academic article that promotes the use of folktales in teaching philosophy to children, and said student is then asked to prepare for a discussion on ethics, she can quickly identify this section of the text (her S-map would contain a section titled ethics/moral issues) and delve further into the section of said essay that discusses the moral and ethical situations that folktales present.

This is one of the ways in which this approach is strategic. It gives the reader the means to find and explore that section of the text that is of use to them and to do so quickly and effectively. In other words, it provides the student with access to a text in English without him or her having to translate it or attempting to read it in the conventional sense. Similarly, if the essay includes a section on the history of folktales that is not of any rhetorical value to the author’s stated thesis, the student can identify this and thus begin a critical evaluation of the source text.

Content Learning

The level of difficulty of the texts should increase as students become more proficient in the use of strategies and develop a greater store of discourse markers. After the first 4 weeks the texts that we work with promote the development of specialized vocabulary and conceptual knowledge required by the philosophy major.

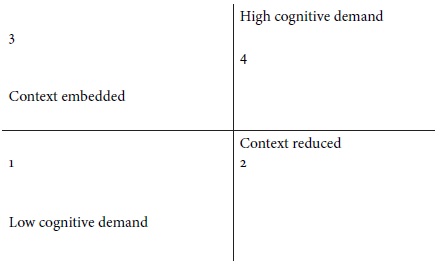

The logic behind how texts are chosen and sequenced is guided by Cummins’ (1992, p. 19) two dimensional model of contextual cues and complexity of task that define the language demands faced by LEP students. The two dimensions can be visualized as a four quadrant chart where the horizontal X is the context (with “embedded” on the left and “induced” on the right) and the vertical Y represents “high” and “low” cognitive demand. The four quadrants formed are: (1) contextualized (embedded) and low cognitive demand, (2) low (induced) context and low cognitive demand, (3) high cognitive demand and contextualized (embedded), and (4) low (induced) context and high cognitive demand. Texts for the three levels of the class were selected so that they progressed from Quadrant 1 to Quadrant 4 (see Appendix D). The kind of texts used evolved from general topics with a low level of cognitive demand and a high degree of embedded context to philosophy-specific topics where the level of explicit context is low and the cognitive demand is high. The hunting practices of owls is an example of a topic for an informative text that would be presented in the first weeks of the initial semester and an article on the foundations and differences between understanding a message or concept and believing it, published in American Psychologist, an example of what students in the final weeks of the third and final level would be asked to map and summarize.

Incorporating Suggestions Into Lesson Plans

The following is a suggested method for integrating the explicit instruction of discourse markers, strategy instruction, and content learning into lesson plans. Learning strategies should be presented as the means toward achieving reading goals. Initially these will require separate mini lessons to explain how they are related to what the student may already do when reading in L1 (awareness), what the nature and function of each strategy is, and how to more effectively pair each strategy with the presented text and the desired reading goals. Beyond this initial introduction however, the MCRs and their strategic use should be considered secondary. They should be seen as the means toward developing an S-map of the texts in question. The motivation behind this is that the strategies should become assimilated into the reading skill sets that the students bring to the classroom and that autonomous and independent use of them should ensue.

I will briefly cover here the manner in which we allocated tasks to time as a point of reference. Twenty percent of our class time was given over to the learning of content, vocabulary, linguistic markers, etc., and 80 percent to strategy instruction and practice. The initial emphasis was on quantity over quality on repeated encounters with new texts so that students worked for 30 or 40 minutes with each text and advanced toward assimilation. Each text served as an opportunity to move closer to a more strategic attitude toward reading; to looking through the text (iteration) with a clear (clearer) purpose in mind, one guided by the search for an answer and not by the left to right and top to bottom movement that extensive or traditional reading promotes.

This high paced work emphasizes that the text in and of itself was of little importance; what mattered, instead, was mastering the practice of extracting the structural and semantic information from it as fast as possible and thus promoting reader control, autonomy, and confidence over the text. This had two important benefits: in standardized reading comprehension, exams time is a crucial factor and being able to attack the text while guided by specific questions will reward the test taker and second, as undergraduates advance through their semesters, the volume and complexity of the readings assigned to them will grow. If they are able to quickly analyze the purpose and structure of a text, they can make decisions as to their usefulness or as to the sections that will serve their specific needs: oral presentations, class discussions, term papers, and critical discussions. In class, activities were carried out by adapting some of the premises of the philosophy of cognitive apprenticeship (Collings, Brown, & Newman, 1989), namely, modeling, diagnosing, fading, and scaffolding. Scaffolding includes providing hints, feedback, reminding, questioning, encouraging, and praising.

The lessons are divided into five stages. Stages 1-3 occupy most of our class time during the initial two weeks. Practice and follow up should be fully incorporated by the fourth to sixth week. During the first stage, students are introduced to the MCRs involved in selective attention, self-monitoring, inferencing, and summarizing. These are to be learned and the sequence of steps needed to implement them. The second stage introduces the S-map as a way to graphically represent, keep track of, and express the relationships between the purpose of the text and the various methods that are used to achieve it. This stage is also used to highlight how many of the tasks students perform while reading in L1 are in fact strategies i.e. strategies that can also be applied to L2 reading. The third stage models the manner and sequence in which the steps in the G-map can be used to respond to multiple choice questions and create an S-map.

Stage 4 is the first practice stage in which the instructor can perform a needs analysis and proceed with complementary instruction to guarantee assimilation of what was covered in Stages 1-3. Stage 5 is the first true autonomous practice stage where the student, in groups or individually, can begin to evaluate his or her own unsuccessful practices and plan accordingly. In summary then, Stages 1 and 2 provide declarative knowledge verbally and graphically, Stage 3 models use, and Stages 4 and 5 serve as practice stages.

For the first four to six weeks, the practice stage should be carried out in cooperative (model) sessions where small groups can develop member confidence in the use of organizational planning, induction, questioning, and grouping strategies called for by the G-map and necessary so that each small group can develop semantic/structural representations of the source text. Classes beyond the sixth week can incorporate more individual or paired work with whole class reviews in the follow-up stage. In the follow-up stage the groups come together as a class to compare the various S-maps and decide where inaccuracies may lie.

Conclusions

Generalization in this field is always a delicate matter; however, there is a strong argument to be made for stating that practitioners may find what this approach offers to be useful in advancing their reading goals with their students. The main characteristics of SIRCA are that it brings together some of the more effective tools available for language teaching and reading comprehension proficiency. These tools include, but are not limited to, the use of metacognitive reading strategies, genre analysis, and task based strategies. From this synthesis come the advantages of adopting this method and the benefits that come from the compounded effectiveness where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. It is also attractive in that its simple structure makes it accessible to a variety of contexts and modifications and that because its skills are transferable from L2 to L1 it can be practiced and perfected outside the English classroom. It empowers students by allowing them quick (albeit limited at first) access to the academic, cultural, and social conversations that take place on the internet and this serves as a powerful motivator for them in achieving their overall language learning and professional goals.

In medicine, the line between research, whose goal is to advance scientific knowledge, and medical practice, which is concerned with a patient’s well-being, is often blurred. On the one hand are physicians who are interested in testing if a drug or procedure works, and on the other, those who rate the same drug or procedure based on whether it helps their patients. The anticoagulant drug Amicar was once routinely prescribed to patients after aneurysm surgery to prevent “re-bleeds”. It worked. Few patients died from “re-bleeds”. They died instead from strokes caused by the interrupted blood flow caused by excessive clotting. The drug did not help. The impetus behind this proposal, if we were to continue the medical metaphor, would fall under innovative treatment rather than research; we are interested in promoting an approach that has helped and may very well continue to do so for other instructors.

1My translation.

2I hesitate to call this a method because although there are specified objectives and selected activities in this instructional design, teacher and student roles are flexible and implementation can be recursive or adaptable to classroom conditions and objectives.

3I present this to students as a gradual evolution from unconscious incompetence to conscious incompetence to conscious competence and lastly to unconscious competence while highlighting that this can be a recursive process and, also, that completely abandoning the earlier strategies is not necessarily the goal but rather visiting them less often or only when new challenges merit it.

4The core lexis is taught early in the course and expanded throughout.

References

Anderson, J. R. (Ed.). (1981). Cognitive skills and their acquisition. Hillsdale, US: Erlbaum.

Anderson, J. R. (1985). Cognitive psychology and its implications (2nd ed.). New York, US: W. H. Freeman.

Barnett, M. A. (1988). Reading through context: How real and perceived strategy use affects L2 comprehension. The Modern Language Journal, 72(2), 150-162. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1988.tb04177.x.

Cambourne, B. (1999). Explicit and systematic teaching of reading: A new slogan? The Reading Teacher, 53(2), 126-127.

Carrell, P. L. (1998). Can reading strategies be successfully taught? Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 21(1), 1-20. http://doi.org/10.1075/aral.21.1.01car.

Chamot, A. U. (2004). Issues in language learning strategy research and teaching. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 1(1), 14-26.

Chamot, A. U., Barnhardt, S., El-Dinary, P. B., & Robbins, J. (1999). The learning strategies handbook. White Plains, US: Addison Wesley Longman.

Collings, A., Brown, J. S., & Newman, S. E. (1989). Cognitive apprenticeship: Teaching the crafts of reading, writing, and mathematics. In L. Resnick (Ed.), Knowing, learning and instruction: Essays in honor of Robert Glaser (pp. 453-494). New York, US: Cambridge University Press.

Cotterall, S. (1990). Developing reading strategies through small-group interaction. RELC Journal, 21(2), 55-69. http://doi.org/10.1177/003368829002100205.

Crystal, D. (1999). English as a global language. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Cummins, J. (1992). Language proficiency, bilingualism, and academic achievement. In P. A. Richard-Amato & M. A. Snow (Eds.), The multicultural classroom: Readings for content-area teachers (pp. 16-26). New York, US: Longman.

Farell, T. S. C. (2001). Teaching reading strategies: ‘It takes time!’ Reading in a Foreign Language, 13(2), 631-646.

Grabe, W., & Stoller, F. L. (2001). Reading for academic purposes: Guidelines for the ESL/EFL teacher. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (3rd ed.) (pp. 187-203). Boston, US: Heinle.

Graham, S., & Harris, K. R. (2000). The role of self-regulation and transcription skills in writing and writing development. Educational Psychologist, 35(1), 3-12. http://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3501_2.

Harris, V. (2003). Adapting classroom-based strategy instruction to a distance learning context. TESL-EJ, 7(2). Retrieved from http://www.tesl-ej.org/wordpress/issues/volume7/ej26/ej26a1/.

Heimlich, J. E., & Pittelman, S. D. (1986). Semantic mapping: Classroom applications. Newark, US: International Reading Association.

Ikeda, M., & Takeuchi, O. (2003). Can strategy instruction help EFL learners to improve reading ability? An empirical study. JACET Bulletin, 37, 49-60.

Informe de gestión del programa de inglés para ingenieros. (2016). Programa de inglés para ingenieros Facultad de Ingeniería. Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia.

Kazemi, M., Hosseini, M., & Kohandani, M. (2013). Strategic reading instruction in EFL contexts. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 3(12), 2333-2342. http://doi.org/10.4304/tpls.3.12.2333-2342.

Khatib, M., & Safari, M. (2011). Comprehension of discourse markers and reading comprehension. English Language Teaching, 4(3), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v4n3p243.

Koda, K. (2004). Insights into second language reading: A cross-linguistic approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lenski, S. D., & Nierstheimer, S. L. (2002). Strategy instruction from a sociocognitive perspective. Reading Psychology, 23(2), 127-143. http://doi.org/10.1080/027027102760351034.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional, men. (2005, December). Bases para una nación bilingüe y competitiva. AlTablero, 37. Retrieved from http://www.mineducacion.gov.co/1621/article-97498.html.

O’Hara, K. (1996). Towards a typology of reading goals (Report EPC-1996-107). Cambridge, UK: Rank Xerox Research Centre.

Osman, H. (2004). Genre-based instruction for ESP. The English Teacher, 33, 13-29.

Palincsar, A. S., & Brown, A. L. (1984). Reciprocal teaching of comprehension-fostering and comprehension-monitoring activities. Cognition and Instruction, 1(2), 117-175. http://doi.org/10.1207/s1532690xci0102_1.

Paris, S. G., Lipson, M. Y., & Wixon, K. K. (1983). Becoming a strategic reader. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 8, 293-316. http://doi.org/10.1016/0361-476X(83)90018-8.

Pressley, M. (2000). What should comprehension instruction be the instruction of? In M. L. Kamil, P. B. Mosenthal, P. D. Pearson, & R. Barr (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (Vol. 3, pp. 545-561). Mahwah, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Pressley, M., & Afflerbach, P. (1995). Verbal protocols of reading: The nature of constructively responsive reading. Hillsdale, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Rhoder, C., (2002). Mindful reading: Strategy training that facilitates transfer. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 45(6), 498-513.

Rosenshine, B., & Meister, C. (1994). Reciprocal teaching: A review of the research. Review of Educational Research, 64(4), 479-530. http://doi.org/10.3102/00346543064004479.

Rubin, J. (1994, March). Components of a teaching education curriculum for learner strategies. Transcript of a colloquium held at the Annual Meeting of the Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages, Baltimore, US. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED376701.

Salataci, R., & Akyel, A. (2002). Possible effects of strategy instruction on L1 and L2 reading. Reading in a Foreign Language, 14(1), 1-16.

Seargeant, P., & Erling, E. J. (2011). The discourse of ‘English as a language for international development’: Policy assumptions and practical challenges. In H. Coleman (Ed.), Dreams and realities: Developing countries and the English language (pp. 2-21). London, UK: British Council.

Shen, H.-J. (2003). The role of explicit instruction in ESL/EFL reading. Foreign Language Annals, 36(3), 424-433. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2003.tb02124.x.

Song, M.-J. (1998). Teaching reading strategies in an ongoing EFL university reading classroom. Asian Journal of English Language Teaching, 8, 41-54.

Waxman, H. C., & Padron, Y. N. (1987). The effect of students’ perceptions of cognitive strategies on reading achievement. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Southwest Educational Research Association, Dallas, US.

Wilson, N. S., & Bai, H. (2010). The relationships and impact of teachers’ metacognitive knowledge and pedagogical understandings of metacognition. Metacognition Learning, 5(3), 269-189. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-010-9062-4.

Zhou, X., & Zhao, Y. (2014). A comparative study of reading strategies used by Chinese English majors. English Language Teaching, 7(3), 13-18. http://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v7n3p13.

About the Author

Juan David Gómez González teaches reading, literature, and rhetoric at Universidad de Antioquia (Colombia). He holds a PhD in English from the State University of New York at Stony Brook (USA).

Appendix A: Reading Comprehension Results

Appendix B: Strategies Employed in SIRCA

The map below aims at identifying the organizing principle of the text by scanning for key words, concepts, and linguistic markers and most importantly, by answering the questions provided here. The cognitive strategies upon which this is based include: classifying concepts and words, abbreviating concepts in written and graphic form, creating a written summary of the information gathered, and relating newly acquired information with established information so as to create a conceptual map of what the text does and how it does so.

Appendix D: Cummins’ (1992) 2 Dimensional Model

Referencias

Anderson, J. R. (Ed.). (1981). Cognitive skills and their acquisition. Hillsdale, US: Erlbaum.

Anderson, J. R. (1985). Cognitive psychology and its implications (2nd ed.). New York, US: W. H. Freeman.

Barnett, M. A. (1988). Reading through context: How real and perceived strategy use affects L2 comprehension. The Modern Language Journal, 72(2), 150-162. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1988.tb04177.x.

Cambourne, B. (1999). Explicit and systematic teaching of reading: A new slogan? The Reading Teacher, 53(2), 126-127.

Carrell, P. L. (1998). Can reading strategies be successfully taught? Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 21(1), 1-20. http://doi.org/10.1075/aral.21.1.01car.

Chamot, A. U. (2004). Issues in language learning strategy research and teaching. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 1(1), 14-26.

Chamot, A. U., Barnhardt, S., El-Dinary, P. B., & Robbins, J. (1999). The learning strategies handbook. White Plains, US: Addison Wesley Longman.

Collings, A., Brown, J. S., & Newman, S. E. (1989). Cognitive apprenticeship: Teaching the crafts of reading, writing, and mathematics. In L. Resnick (Ed.), Knowing, learning and instruction: Essays in honor of Robert Glaser (pp. 453-494). New York, US: Cambridge University Press.

Cotterall, S. (1990). Developing reading strategies through small-group interaction. RELC Journal, 21(2), 55-69. http://doi.org/10.1177/003368829002100205.

Crystal, D. (1999). English as a global language. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Cummins, J. (1992). Language proficiency, bilingualism, and academic achievement. In P. A. Richard-Amato & M. A. Snow (Eds.), The multicultural classroom: Readings for content-area teachers (pp. 16-26). New York, US: Longman.

Farell, T. S. C. (2001). Teaching reading strategies: ‘It takes time!’ Reading in a Foreign Language, 13(2), 631-646.

Grabe, W., & Stoller, F. L. (2001). Reading for academic purposes: Guidelines for the ESL/EFL teacher. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (3rd ed.) (pp. 187-203). Boston, US: Heinle.

Graham, S., & Harris, K. R. (2000). The role of self-regulation and transcription skills in writing and writing development. Educational Psychologist, 35(1), 3-12. http://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3501_2.

Harris, V. (2003). Adapting classroom-based strategy instruction to a distance learning context. TESL-EJ, 7(2). Retrieved from http://www.tesl-ej.org/wordpress/issues/volume7/ej26/ej26a1/.

Heimlich, J. E., & Pittelman, S. D. (1986). Semantic mapping: Classroom applications. Newark, US: International Reading Association.

Ikeda, M., & Takeuchi, O. (2003). Can strategy instruction help EFL learners to improve reading ability? An empirical study. JACET Bulletin, 37, 49-60.

Informe de gestión del programa de inglés para ingenieros. (2016). Programa de inglés para ingenieros Facultad de Ingeniería. Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia.

Kazemi, M., Hosseini, M., & Kohandani, M. (2013). Strategic reading instruction in EFL contexts. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 3(12), 2333-2342. http://doi.org/10.4304/tpls.3.12.2333-2342.

Khatib, M., & Safari, M. (2011). Comprehension of discourse markers and reading comprehension. English Language Teaching, 4(3), 1-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/elt.v4n3p243.

Koda, K. (2004). Insights into second language reading: A cross-linguistic approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lenski, S. D., & Nierstheimer, S. L. (2002). Strategy instruction from a sociocognitive perspective. Reading Psychology, 23(2), 127-143. http://doi.org/10.1080/027027102760351034.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional, men. (2005, December). Bases para una nación bilingüe y competitiva. AlTablero, 37. Retrieved from http://www.mineducacion.gov.co/1621/article-97498.html.

O’Hara, K. (1996). Towards a typology of reading goals (Report EPC-1996-107). Cambridge, UK: Rank Xerox Research Centre.

Osman, H. (2004). Genre-based instruction for ESP. The English Teacher, 33, 13-29.

Palincsar, A. S., & Brown, A. L. (1984). Reciprocal teaching of comprehension-fostering and comprehension-monitoring activities. Cognition and Instruction, 1(2), 117-175. http://doi.org/10.1207/s1532690xci0102_1.

Paris, S. G., Lipson, M. Y., & Wixon, K. K. (1983). Becoming a strategic reader. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 8, 293-316. http://doi.org/10.1016/0361-476X(83)90018-8.

Pressley, M. (2000). What should comprehension instruction be the instruction of? In M. L. Kamil, P. B. Mosenthal, P. D. Pearson, & R. Barr (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (Vol. 3, pp. 545-561). Mahwah, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Pressley, M., & Afflerbach, P. (1995). Verbal protocols of reading: The nature of constructively responsive reading. Hillsdale, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Rhoder, C., (2002). Mindful reading: Strategy training that facilitates transfer. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 45(6), 498-513.

Rosenshine, B., & Meister, C. (1994). Reciprocal teaching: A review of the research. Review of Educational Research, 64(4), 479-530. http://doi.org/10.3102/00346543064004479.

Rubin, J. (1994, March). Components of a teaching education curriculum for learner strategies. Transcript of a colloquium held at the Annual Meeting of the Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages, Baltimore, US. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED376701.

Salataci, R., & Akyel, A. (2002). Possible effects of strategy instruction on L1 and L2 reading. Reading in a Foreign Language, 14(1), 1-16.

Seargeant, P., & Erling, E. J. (2011). The discourse of ‘English as a language for international development’: Policy assumptions and practical challenges. In H. Coleman (Ed.), Dreams and realities: Developing countries and the English language (pp. 2-21). London, UK: British Council.

Shen, H.-J. (2003). The role of explicit instruction in ESL/EFL reading. Foreign Language Annals, 36(3), 424-433. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2003.tb02124.x.

Song, M.-J. (1998). Teaching reading strategies in an ongoing EFL university reading classroom. Asian Journal of English Language Teaching, 8, 41-54.

Waxman, H. C., & Padron, Y. N. (1987). The effect of students’ perceptions of cognitive strategies on reading achievement. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Southwest Educational Research Association, Dallas, US.

Wilson, N. S., & Bai, H. (2010). The relationships and impact of teachers’ metacognitive knowledge and pedagogical understandings of metacognition. Metacognition Learning, 5(3), 269-189. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-010-9062-4.

Zhou, X., & Zhao, Y. (2014). A comparative study of reading strategies used by Chinese English majors. English Language Teaching, 7(3), 13-18. http://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v7n3p13.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

CrossRef Cited-by

1. María Mercedes Hernández, Ligia Ochoa Sierra. (2023). Papel de los marcadores discursivos en la comprensión lectora. Cuadernos de Lingüística Hispánica, (40), p.1. https://doi.org/10.19053/0121053X.n40.2022.15501.

2. Mabel O. Rivera, Glennda K. McKeithan. (2022). Progress Monitoring of Language Acquisition and Academic Content for English Learners. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 37(3), p.216. https://doi.org/10.1111/ldrp.12290.

Dimensions

PlumX

Visitas a la página del resumen del artículo

Descargas

Licencia

Derechos de autor 2017 PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development

Esta obra está bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivadas 4.0.

Los contenidos de la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development son de acceso abierto y los cubre la Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivar 4.0 Internacional. Se autoriza copiar, redistribuir el material en cualquier medio o formato, siempre y cuando se conceda el crédito a los autores de los textos y a la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development como fuente de primera publicación. No se permite el uso comercial de copia o distribución de contenidos, así como tampoco la adaptación, derivación o transformación alguna de estos sin la autorización previa de los autores y de la Editora de la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.

Los autores conservan la propiedad intelectual de sus manuscritos con la siguiente restricción: el derecho de primera publicación es otorgado a la revista Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.