Published

Policies for English Language Teacher Education in Brazil Today: Preliminary Remarks

Políticas para la formación de profesores de inglés en el Brasil de hoy: primeras aproximaciones

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n1.48740Keywords:

Brazil, education, English as a foreign language, policy, programs (en)Brasil, educación, inglés como lengua extranjera, política, programas (es)

In the last decade Brazil has begun to tackle the educational challenges of a developing country with a young population. The scale of such a demand is a result of the social and cultural inequalities that have historically been existent. Recent official policies and programs have addressed this gap by promoting greater opportunities for teacher education, and for the teaching of English as a foreign language. In this paper we discuss four of these programs/policies by highlighting their innovative aspects vis-à-vis traditional practices. We conclude that, despite quantitative advances, much still needs to be done to guarantee qualitative improvements in areas such as the curriculum in order to challenge the continuing influence of predominant ideologies.

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n1.48740

Policies for English Language Teacher Education in Brazil Today: Preliminary Remarks

Políticas para la formación de profesores de inglés en el Brasil de hoy: primeras aproximaciones

Telma Gimenez*

Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Londrina, Brazil

Aparecida de Jesus Ferreira**

Universidade Estadual de Ponta Grossa, Ponta Grossa, Brazil

Rosângela Aparecida Alves Basso***

Universidade Estadual de Maringá, Maringá, Brazil

Roberta Carvalho Cruvinel****

Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiânia, Brazil

*tgimenez@uel.br

**aparecidadejesusferreira@gmail.com

***rbasso@uem.br

****cruvinelroberta@gmail.com

This article was received on February 3, 2015, and accepted on July 10, 2015.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Gimenez, T., Ferreira, A., Alves Basso, R. A., & Carvalho Cruvinel, R. (2016). Policies for English language teacher education in Brazil today: Preliminary remarks. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 18(1), 219-234. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n1.48740.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

In the last decade Brazil has begun to tackle the educational challenges of a developing country with a young population. The scale of such a demand is a result of the social and cultural inequalities that have historically been existent. Recent official policies and programs have addressed this gap by promoting greater opportunities for teacher education, and for the teaching of English as a foreign language. In this paper we discuss four of these programs/policies by highlighting their innovative aspects vis-à-vis traditional practices. We conclude that, despite quantitative advances, much still needs to be done to guarantee qualitative improvements in areas such as the curriculum in order to challenge the continuing influence of predominant ideologies.

Key words: Brazil, education, English as a foreign language, policy, programs.

En la última década, Brasil ha comenzado a afrontar los retos educativos de un país en desarrollo con una población joven. La escala de tal demanda es el resultado de las desigualdades que se han producido históricamente. Políticas y programas oficiales recientes han abordado este vacío mediante la promoción de mayores oportunidades para la formación del profesorado, y para la enseñanza del inglés como lengua extranjera. En este artículo discutimos cuatro de estos programas/políticas, poniendo de relieve sus aspectos innovadores frente a las prácticas tradicionales. Llegamos a la conclusión de que, a pesar de los avances cuantitativos, aún queda mucho por hacer para garantizar mejoras cualitativas en áreas tales como el plan de estudios para contraponerse a la continua influencia de las ideologías predominantes.

Palabras clave: Brasil, educación, inglés como lengua extranjera, política, programas.

Introduction

We are Brazilian postgraduate foreign language researchers developing studies regarding the current educational scenario in our country. In this article we discuss some developments resulting from the adoption of policies aimed at teacher training in light of the implementation of the National Policy for the Education of School Teachers and the internationalization of academic production represented by the “Science without Borders” program. Our focus is on the following four different policies and programs: the National Development Plan for Teachers in Public Educational Systems and Network (PARFOR), the Professional Development Program for Teachers of English in The United States (PDPI), English without Borders, and the National Policy for Inclusion and Diversity. All these policies/programs bring with them consequences for the teaching and learning of the English language, which is our field of expertise, and which is an area that has been greatly affected by the processes of globalization (Park & Wee, 2014; Ricento, 2015; Rubdy & Saraceni, 2006). We argue that these initiatives are an attempt to tackle the gaps in the field of teacher or language education by exhibiting (dis)continuities that reveal the complexity of policy enactment (Ball, Maguire, & Braun, 2012). These policies and programs share the common purpose of improving the existing educational outcomes of public education in order to create a fairer and more democratic society that embraces the rich variety of the country’s cultural resources and, at the same time, establishes links with a global perspective. In response to the National Policy for Teacher Education, which was implemented in 2009 with the purpose of guiding and regulating teacher education initiatives, and the launching of the “Science without Borders” program, both traditional and innovative practices have been designed and implemented. These practices have resulted in a mix that reflects continuities and, at the same time, points to new developments. The hybrid nature of these policies exemplifies their inherent tensions because they attempt to introduce new practices while accommodating established norms and habitus.1

Our reflections are grounded on the notion that policies are processes that are discursively represented and that they are subject to “interpretations” as they are enacted (Ball et al., 2012). These interpretations are made concrete through specific actions by different actors when they engage in social activity that is imprinted with meanings, and those meanings can be traced back to those policies. From this perspective, policies cannot be completely understood without considering the interface that exists between texts, practices, and understandings. In the four examples addressed in this text, we discuss elements of habitual practices and innovations which are mingled, as the policies create the “circumstances in which the range of options available in deciding what to do are narrowed or changed, or particular goals or outcomes are set” (Ball, 1994, p. 19).

In the following sections each author will present her own perspective on the challenges posed by these educational policies or programs by discussing their relevance to the declared goal of narrowing educational gaps in Brazil, which have been associated with the maintenance of social and cultural inequalities for a long time.

PARFOR—National Development Plan for Teachers in Public Educational Systems and Network

This program was created based on the premise that education is a public good and therefore everybody is entitled to it. It is a means to human development so that democratization of access and the expansion of higher education is part of an agenda aimed at social inclusion (Nussbaum, 2011; Nussbaum & Sen, 1993; Walker & Unterhalter, 2007). In this context policies and programs emerge as new possibilities for educational, political, and social outcomes. Although the great expansion of higher education occurred over the past years there still are some disparities among social groups and places (McCowan, 2013).

As a developing country, Brazil is striving to include a larger percentage of its youth in higher education. According to the National Institute of Studies and Research (INEP, 2005), in 2001 Brazil had only 12.1% of its young people studying at this level, the smallest percentage in Latin America. Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay reached a corresponding level of 30% in 2002 (Sguissardi, 2006). In addition, Brazil needs to qualify 400,000 in-service teachers in order to meet the declared governmental goal of educating 30% of the population from ages 18-24, as established by the National Plan for Education—PNE (2001-2011). In order to achieve this goal, in 2009 the government launched, among others policies and programs, an emergency program called PARFOR, which was financed by CAPES, an agency linked to the Ministry of Education. The program is to be developed in collaboration with state secretariats, municipalities, and higher education institutions by offering: (a) face-to-face undergraduate courses as a first degree; (b) a complementary second degree for those already holding a degree (e.g., a Portuguese language teacher who takes Spanish as a second qualification); and (c) pedagogic development for sign language teachers. Primarily, the program was developed due to the large number of in-service teachers who do not hold a degree in the subject they are teaching (e.g., Portuguese language teachers who also teach English without holding a degree in English). For those teachers the program offers a complementary second degree to increase teachers’ qualification.

PARFOR courses are offered by 106 public universities and 32 non-profit private institutions; they have to take into account regional and local demands as well as teachers’ professional needs. Due to the demand across Brazil, in 2013 PARFOR offered 361,020 places for students to be enrolled in the following three categories: 71.07% first degree; 26.31% second degree; and 2.62% pedagogic development.2 However, only 30% of the total places were taken.3 Pedagogy leads the ranking with 15.46%, due to the fact that according to the PARFOR report for 2009-2013, only 68% of Portuguese language in-service teachers had a degree. In terms of foreign languages, 3.82% of English teachers had a degree and 2.61% of Spanish teachers (Fundação CAPES, 2013).

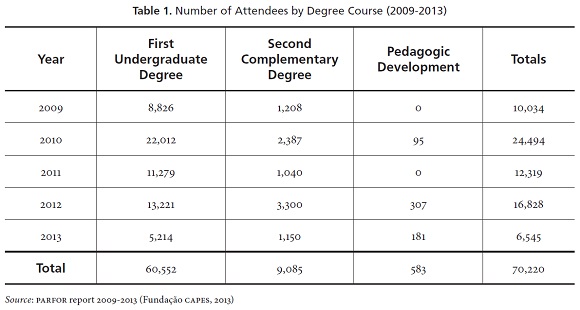

To give an idea of the scale and scope of PARFOR, between 2009 and 2013 the program offered 2,145 classes in 422 municipalities in 24 states, with 70,220 attendees. In 2013, the greatest number of places for student enrollment was from municipalities in the interior of the country, where demand is higher. Table 1 shows these numbers in detail.

Additionally, the widespread reach of the program can be exemplified by the number of schools involved: in 2013 there were 24,380 participating schools, with at least one teacher from each school enrolled (CAPES, 2013). The challenges of such an endeavor are huge due to the continent-like size of Brazil. Furthermore, the professional duties of the participating teachers means that the courses have to be attended during weekends and school holidays (June and January), and teacher educators have to travel to schools in journeys that can take up to 10 hours or more either by car or by boat. This is the case of the Amazon region, where most of the schools are in remote areas. According to the PARFOR report for the period 2009-2013 (CAPES, 2013), the two biggest states from the Northern region of Brazil, Pará and Amazon, reached levels of 71.49% and 62.37%, respectively, for in-service teachers attending their first undergraduate degree, as shown in Table 2. This means that, in these regions PARFOR has reached one of its goals to qualify in-service teachers to improve the quality of education.

Regarding the education of language teachers, PARFOR targets Spanish (26 groups), English (43 groups), and Portuguese and English (19 groups), totaling 88 groups, predominantly in states located in the north and northeast regions. Given a high level of demand in comparison with other states, the state of Pará contains the largest number of groups enrolled in courses offered by two public universities: Spanish (3 groups), English (19) and Portuguese and English (19). In relation to English language teachers, who are the focus of this paper, there are about 2,140 participants, which represent 73% of the workforce. This means that currently, there are a great number of teachers teaching English without proper qualifications (Pará State Secretary of Education, 2014).

Preliminary assessments reveal that PARFOR has reached its goal across the country, especially in the regions where people have restricted access to qualification and higher education opportunities. The innovative aspects associated with PARFOR are related to a modality which considers the existing professional milieu of practicing teachers and supplies professional development in a manner that makes it feasible for teachers to participate.

As this contextualization reveals, the teaching of English in Brazilian schools is carried out in less than ideal conditions, a situation in need of change and which has been addressed by initiatives such as PARFOR. Another program launched by the government in 2011 both exposed and also tried to remedy the deficient educational outcomes in this area. Although it did not have teacher education as a goal, this program has the potential spinoff of creating opportunities for initial English language teacher education.

English without Borders

The “English without Borders” (EwB) program was launched in 2013 as an ancillary program to “Science without Borders” (SwB)—an initiative at the federal level to raise the academic profile of the country at the international level. The SwB program offers scholarships to academics (mainly undergraduate students) to complete part of their education abroad in prestigious higher education institutions. The duration of such experience varies, but in general during six months to one year the students develop projects and engage with research groups in strategic areas for development, such as biotechnology, computer science, renewable energy, creative industry, among others. As such, it follows the worldwide trend for the internationalization of higher education, another step towards a globalized academia that draws mainly on English to carry out its teaching/research activities. According to the SwB website (Science without Borders, 2014) the program is justified as follows:

Every highly qualified academic or research center around the globe is experiencing an intense process of internationalization, increasing its visibility and addressing the needs of today’s globalized world. Brazilian institutions need to rapidly engage in this process since several factors still hinder a more international view of the Science made in the country. The educational system, for instance, has no current actions aimed to effectively amplify the interaction of native students with other countries and cultures. (para. 2)

In addition to revealing the aspirations of Brazilian higher education institutions (to be highly qualified, become visible, and address the needs of a globalized world), the description hints that several factors prevent this aspiration from becoming reality. Although there are no official national language proficiency assessments in Brazil, informal surveys carried out in 2014 by an independent organization revealed that Brazil was ranked number 38 in terms of English language proficiency among 63 countries (English First, 2014). That poor record can partly be explained by the historical lack of policies aimed at improving the teaching of foreign languages in schools. The outcomes of this negligence were clear: the program administrators soon found out that the applicants to participate in SwB (mostly undergraduate students) could not achieve the levels required by the majority of the universities in English speaking countries or those with English as a medium of instruction. EwB was thus created to help raise those proficiency levels so as to enable the awarding of approximately 100,000 scholarships by the year 2015. One of the requirements for potential candidates is a satisfactory command of English, as represented by the scores defined by the receiving institution.

A series of measures aim at implementing such a program; a management team, coordinated by academics, is in charge of follow-up activities carried out in 63 federal universities, 20 state universities and 30 federal institutes. These activities include: the administration of placement tests (mainly TOEFL ITP); the offer of online courses (My English Online); and face-to-face language courses offered by universities, which are funded by the federal government. These courses aim at preparing students to succeed in proficiency tests such as TOEFL and IELTS. Each participating university associated with EwB defines their capacity to administer the tests and teach the face-to-face classes. They receive funding according to that capacity.

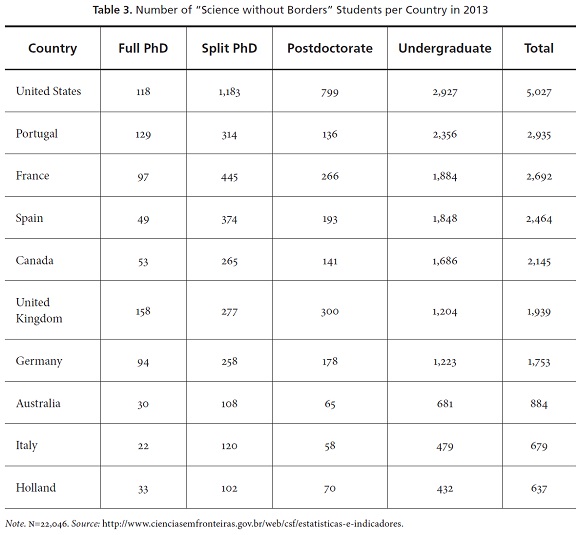

English plays a vital role in the SwB operations. Table 3 shows the 10 main countries of destination for scholarship recipients.

Given that these data are from 2013 (no updates were available at the time of writing), one can see that in the first years of the program the majority of the candidates went to countries where English is either the first language or is used as a medium of instruction. The fact that Portugal appears as the second choice is testament to the fact that language proficiency was an issue (Portuguese is the official language in Brazil) at the earlier stages of the program and justifies the low percentage of scholarships awarded so far.

Both the scale and range of actions at a national level are unprecedented. Many of those directly involved highlight the satisfaction of having a foreign language finally being the object of public policies, with funding from the government (Abreu, 2014). Two key points have been reported as positive outcomes: the involvement of academics in all stages of the program and the extension of similar actions to other foreign languages, to the point that EwB now forms part of “Foreign Languages without Borders,” a broader program that includes Portuguese as a foreign language.

These recent developments suggest that this policy is “in the making,” since one of its paradoxes had not yet been addressed: a policy that depends heavily on the knowledge of foreign languages (especially English) was launched without actions that would improve the language proficiency of potential candidates. If the creation of EwB (and now its extension) is a sign of the policy’s porous nature, it is also true that the original version of SwB had short-term goals, due to the political uncertainties surrounding the potential reelection of the incumbent President.4

The acknowledgement that long-term policies would have to incorporate teacher education initiatives, and the absence of the humanities area in the SwB program, coupled with the diplomatic efforts to increase the presence of the Portuguese language abroad, can be seen as justifications for that inclusion. This addition has the strategic purpose of attracting students to Brazilian universities, thus giving a “green and yellow”5 color to the internationalization of higher education. At the same time, the expansion of the program to include other languages (French, Italian, Spanish, German, Japanese, and Mandarin) goes against the tide of English as medium of instruction. Brazilian policies seem to be favoring both the development of English language proficiency for the majority of the SwB candidates and the enhancement of the teaching of other foreign languages, although on a much smaller scale. Despite the potential danger of being accused of paying lip service to multilingualism, this decision points to a promising direction that establishes the value of learning a foreign language.

Considering that the English language is the second language most taught in Brazilian state schools, those in charge of offering the EwB courses are also teacher educators in languages courses, where prospective English language teachers receive their preparation. It seems inevitable that the effects of the program will spill over into that preparation, since those student teachers with higher levels of proficiency are being invited to serve as instructors in the preparatory language courses offered by universities to potential SwB candidates. It is as yet unknown if the approach adopted to teach in state schools (favored by languages courses) will be the same as that which will be used in the university language courses, and how that could impact on the conceptualizations of novice teachers (still student teachers) regarding language teaching and learning. At first sight it seems that these are two different educational contexts, with separate learning objectives and goals, but it is likely that some convergence will result from the arrangement, especially if the goal of state school education is seen as a step towards participation in the SwB program. The presentation of several papers and symposia at two recent events about teacher education in connection with the program6 are indications that although initial teacher education was not envisaged, the EwB program is engendering new practices and creating new meanings for novice teachers of English.

We are still at the early stages of this policy but it is possible to identify that its enactment has been creatively constructed: It limits and frames spaces for action by English language teacher educators, but at the same time it also allows them the freedom to imprint new directions. This freedom also poses one of the challenges for those teacher educators; how to deal with the competing discourses about English as a lingua franca (ELF) and standard English.

The innovative aspects of the policy are clear: English, and now other foreign languages, is the object of the government’s attention. However, these innovations are carried out in tandem with more traditional precepts in English language teaching. By that, we mean specifically the fact that the English language is assumed to be the language of native speakers, thus subscribing to a view that as long as the candidates learn to use American or British English (as reflected in the TOEFL ITP/IBT and IELTS options), they will be able to communicate in academic settings. This situation reveals a tension between more recent academic discourses about ELF and English as a native language (Gimenez, Calvo, & El Kadri, 2011; Mauranen, 2012; Seidlhofer, 2011). The preference for the American variety can be seen in the choice of placement tests administered to about 500,000 candidates, the platform My English Online—which is provided by Cengage Learning and National Geographic—and the courses at the institutions to prepare candidates to successfully achieve the necessary language proficiency scores. In this sense, the decisions regarding which variety to privilege follow a traditional curriculum, in which the native speaker is taken as the model.

Although the literature on ELF argues for the need to consider the diversity of the English language and its appropriation by speakers in different parts of the world, calling into question central tenets of linguistic theory (Widdowson, 2000, 2012), the enactment of the Brazilian internationalization policy has to rely on what is practically achievable. In the words of one of the members of the management team:

The choices are made depending on the partnerships established by the Program. The aim is not to privilege any variety of English. All the English language speaking countries’ embassies, governments and universities are in touch with the EwB managing team in order to set new partnerships. A single partnership with only one country could not take into account all of our needs. There are ongoing negotiations with other countries, but due to the worldwide crisis, it hasn’t been easy for the partners to contribute with the Program. (Questionnaire, September 2014) (Gimenez & Passoni, 2014, p. 6)

Despite the recognition that there are other varieties of English, these are restricted to the so-called “Inner Circle” countries (Kachru, 1986) and thus the arguments presented by ELF researchers do not find fertile ground, perhaps because practical considerations have to be taken into account (Gimenez & Passoni, 2014). High-stakes tests such as the ones used by SwB play a central role in the choice of teaching materials and curriculum decisions. While the academic field debates whether lingua franca communication can lead to the characterization of a new variety of English (and its legitimation through grammar books, dictionaries, and internationally recognized tests), the practical world of policy enactment, although led by academics, carries on with what is available, thus reinforcing the tradition in English language teaching that favors native speaker varieties. It is to the practical world, where ideologies of the native speaker as the ideal norm thrive, that we turn next.

PDPI—Professional Development Program for English Teachers in the United States of America

The goal of improving the teaching of English in public schools, a need which was highlighted by the SwB program, is shared by the PDPI. This program was conceived to create opportunities for public school teachers to improve their skills in a country where English is the first language. It is coordinated by CAPES in partnership with the US Embassy in Brazil and the Fulbright Commission, with the support of the National Council of Education Secretaries (CONSED). Its aims, as expressed in its website7 are:

- To strengthen the teacher’s oral and written fluency in English.

- To share teaching and evaluation methodologies to encourage student participation in the classroom.

- To encourage the use of online resources and other tools both in the continuing education of teachers and in the preparation of lesson plans.

The objectives of the program hint at what is considered to be deficient: the poor language competence of teachers, methodologies that discourage student participation, and the lack of use of online technologies.

In order to tackle these “deficiencies,” in its initial phase, the program selected 70 participants,8 who were divided into three groups and who attended an eight-week course at the University of Oregon (Eugene, USA) on different occasions (2011 and 2012). During the course, the teachers had classes in English, culture and history, technology, the theory and practice of language teaching methodologies, and pair meetings with tutors. The teachers also had the opportunity of face-to-face class observations during visits to local schools, and participated in cultural events. The American English Institute faculty of the University of Oregon also provided practical workshops on a variety of topics.

The second phase, in 2013, selected 540 parti-cipants who went to different universities across the United States to attend a six-week program divided into two course modalities: methodology and language development. The former was designed for teachers with advanced knowledge in English in order to develop and/or learn new teaching and learning methodologies; the latter was aimed at teachers who needed to improve specific skills in English. In the third edition, the program selected another group of 540 participants, also for an intensive six-week course in 2014, also in different universities, following the same format as the second edition.

The preparation of teachers of English in countries where it is a native language is not a novelty, especially if we consider the various exchange programs promoted by American or British agencies in the decades following the end of World War II (Gimenez, Serafim, & Alonso, 2006). However, the current efforts by Brazilian and American institutions are introducing two new elements: first, a focus on school teachers, as opposed to university professors, who were the professionals targeted by those exchange programs, and second, the scale of the PDPI. In the past, very few English language schoolteachers had the opportunity to go abroad for development. These new elements can be explained by the pressing need to improve the learning of English in schools and the size of the demand for teacher education, as the statistics presented in the previous sections make clear.

Despite its attempt to address one of the many challenges facing the Brazilian educational system, the PDPI runs the risk of reinforcing the view that native speakers “know best,” a view that goes against the idea of the importance of the empowerment of local knowledge. An initial investigation of some participants’ views9 confirms this possibility:

As we had our English classes with other students from all over the world, I think that our placement in the oral skills class was not well analyzed. We were all teachers and didn’t learn a lot in these classes. It would be better to take a course at the university within a specific program designed for us. I really don’t think the oral skills classes were productive. Another point to mention is about our meetings with the tutors. Those students who had good tutors were able to improve their English. However, usually they were first year university students, with little experience, very young, and they did not have much empathy. (Elis, Interview, our translation from Portuguese)

Although it is well intended, there is a risk that, by sending teachers abroad, the local realities will not be considered, no matter how satisfactory the experience is from the point of view of living in an English-speaking country, even if for a short while.

Holliday (2011) also notes that the predominant cultures of countries where English is a native language can have an overwhelming influence over local cultures, and he favors a view of the language that goes beyond national borders. A program like the PDPI tends to reinforce those boundaries since it assumes a detached view of teaching methodologies, one that can be transposed anywhere in the world. The importance of the context cannot be minimized in programs like this.

Nevertheless, it is also necessary to consider the fact that going abroad, albeit for a few weeks, produces effects in terms of subjective evaluations of the experience, as the following excerpt demonstrates:

The experience I had in the US contributed to my enhancement. The possibility of immersion undoubtedly helped me to be more fluent and it gave me some empowerment. I feel more confident with my English. When I came back I brought the proposal to school, to speak only in English here. (Laila, Interview, our translation from Portuguese)

The fact that teachers travel to the United States both reinforces the ideology of the native speaker as the norm for English language teaching in Brazil and also assigns prestige to those participants. In this sense, participating teachers accumulate symbolic capital and have their identities as teachers legitimized by that participation, when, for instance, their students value them more as teachers because of their experience abroad. It seems, therefore, that the PDPI works mainly to improve the self-esteem of teachers and to boost their confidence. However, due to the lack of follow up studies we cannot assert whether it actually changes classroom practices. It is in the classroom, after all, where the aforementioned programs really matter. In the next section we will discuss a policy that aims at producing new subjectivities by addressing issues of race.

Policy for Diversity and Inclusion

In the previous sections we have presented data and discussed how some policies have been enacted in Brazil and the challenges they pose to those responsible for making them happen. The same is true for the policies implemented by the Brazilian government regarding the issues of inclusion and diversity. In the last fifteen years, Brazilian administrations have been trying to create a fairer and more democratic society through educational and linguistic policies which have direct implications for the education of teachers of English as a foreign language (EFL). This issue is the focus of the following section.

Although these policies are broad and include issues of inclusion, we will focus in this section on the issue of race, which is understood in this specific context as a socially-constructed phenomenon (Giddens, 1989).

One important aspect about Brazil is that it is often referred to as a “color blind” country which celebrates the so-called “myth of racial democracy.” This means that some Brazilians claim that they believe that people’s skin color is unimportant, or that Brazil is a multicultural society without problems related to racism. However, many statistics and a large body of research, unequivocally show that Brazil is a country that has many problems regarding inequality that are related to race, and that these problems also intersect with issues of social class and gender. For these reasons, as mentioned above, incorporating the issue of racial identity into the curriculum is important, not just in the general field of education, but also in the fields of applied linguistics and EFL. Such developments demonstrate that the area of EFL in Brazil is attuned to what is happening worldwide in terms of tackling inequality and bringing to the discipline discussions about a more diverse, inclusive society.

One of the important initiatives related to the promotion of diversity and inclusion in the school curriculum was the publication of the National Curriculum Parameters of Foreign Languages in 1998 (Ministério da Educação [MEC], 1998). These guidelines introduced the concept of cross-curricular themes and strengthened the need to bring to the fore issues relating to inclusion and diversity, mainly in the area of cultural plurality, within which we can locate race and ethnicity.

Another important policy change was the publication in 2003 of Federal Law 10.639/2003, which made the teaching of African history and Afro-Brazilian culture compulsory in the school curriculum. As a result of that mandatory orientation, since 2003 all university courses in Brazil, including those aimed at EFL teaching (MEC, 2004) have to include in their teacher education curricula approaches to address racial identity in the classroom. This legislation was a response to an international agreement signed in 2000, during a meeting in South Africa (The Durban Declaration10), designed to tackle the issue of inclusion; one of the aspects specifically mentioned was racism.

Even though Brazilian legislation and the curriculum guidelines made the inclusion of issues of race and racism compulsory, teacher educators allege that there is not enough space allocated within the curriculum to reflect on the issue deeply enough to give them confidence (Azevedo, 2010; Camargo, 2012; Ferreira, 2009; Melo, Rocha, & Silva Júnior, 2013; Urzêda-Freitas, 2012). This means that the EFL teacher educators and curriculum developers at the university level need to make an effort to include the issue of racial identity in their curricula.

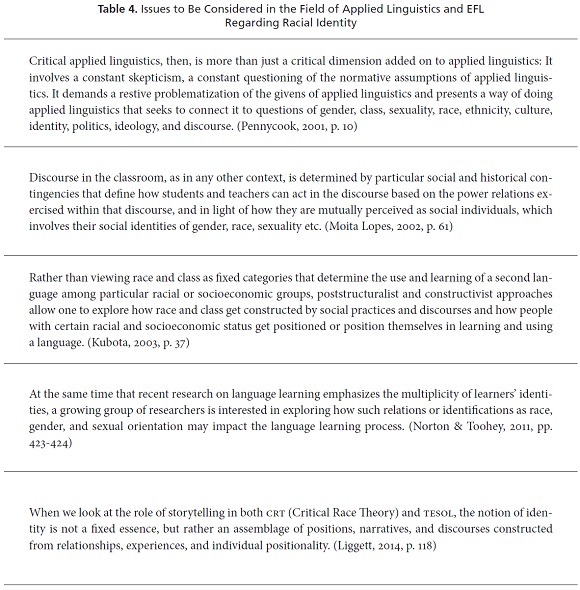

Despite these criticisms, there have been some advances concerning research that addresses the importance of raising awareness of racial issues in the EFL curriculum, as the literature produced in Brazil has shown (Ferreira, 2006, 2012, 2014; Moita Lopes, 2002; Pessoa, 2014; Santos, 2011; Silva, 2009). These discussions are aligned with research outside Brazil that emphasizes the need to include the issue of racial identity in English language teaching and TESOL (Teaching of English to Speakers of Other Languages). Table 4 demonstrates the main arguments by those scholars in relation to racial identity.

As can be seen from Table 4, the area of applied linguistics around the world is highlighting the importance of addressing racial identity as part of education within the field of EFL. In this sense, applied linguists and EFL teacher educators need to address issues that are related to their localities and social practices: in the case of Brazil and many other countries, race is an issue that demands reflection (Ferreira, 2007). In this sense, it seems that Brazilian society is advancing in terms of educational and linguistic policies, as discussed above. However, EFL teaching courses still need to be more proactive in terms of inserting these discussions in curricula, which unfortunately is not happening throughout Brazil. Considering that when English is taught, or when teachers are prepared to teach English, this occurs through the medium of discourse, then that discourse should be permeated by peoples’ identities regarding race, which remains a fundamental issue in Brazilian society, and many others worldwide.

Conclusions

The policies and programs presented in this text directly or indirectly address some of the challenges of educating English language teachers in Brazil. Framed within the larger goals of meeting the demand for teachers, among which English language professionals are given prominence, these initiatives reveal the efforts of Brazilian authorities to provide greater access to improved learning opportunities.

We presented the macro indicators for PARFOR, which showed that although large numbers of teachers are enrolled in teacher education courses, there is still more work to be done in this respect in order to achieve the purpose of promoting human development in remote areas. The northern region of Brazil is the area that has been most successful, and it is the area where demand for these courses has been considerably higher than in other regions. Some innovative aspects of this program are the possibility of practicing teachers obtaining a second degree, and the preparation of teachers to use sign language. Traditional elements can be seen in the curricula of these courses, which follow the existing paradigm of pre-service teaching, thus ignoring the fact that that course participants already have teaching experience.

Two other initiatives explicitly aimed at the improvement of English language proficiency—the EwB and PDPI—reveal the interconnections between local and global pressures, as teachers face dilemmas about how to deal with the ideologies of English as a native language and ELF. Some innovative aspects of these initiatives are the special attention given to foreign languages, with funding from the federal government, and the scale of the opportunities given to Brazilians to study abroad. Some traditional aspects can be seen in the curriculum of the PDPI and the assessment choices of EwB, which reinforce the idea that native speakers’ English is the goal to be achieved, despite the diversity of situations in which language users will need to communicate.

In relation to the policies aimed at recognizing issues of diversity and inclusion, we singled out the issue of race in order to point out that recent legislation has created the need for teachers to be educated in how to deal with racism in English language classes. We have shown that despite a prolific literature, both in Brazil and abroad, supporting this perspective, much remains to be done. Some examples of innovative aspects of this policy are the recognition that race is integral to the Brazilian constitution society and the fact that so-called “color blindness” needs to be examined critically. Some traditional aspects of this policy can be seen in the way that teacher education programs have dealt with this mandate, largely ignoring its implications in languages courses.

As Ball et al. (2012) have highlighted, policies can be represented in different ways by different actors. As academics, we brought out our representations about recent Brazilian educational policies. From this perspective, we chose to present them in terms of their goals and achievements, seeing in them elements of both tradition and innovation. The enormous challenge of educating teachers to supply the growing demand of a developing country in the context of globalized policies was touched upon. We identified the new opportunities that have been offered to professionals, but we also noted that the concern with quantity may have put qualitative assessments (such as specific curricula for in-service teachers, the use of English as a lingua franca, and professional preparation for a racially sensitive curriculum) in second place, enabling traditional practices to continue to flourish.

1According to Bourdieu (1977), the concept of habitus refers to a set of acquired knowledge with dispositions that are incorporated through life; “dispositions that are both shaped by past events and structures, and that shape current practices and structures and also, importantly, that condition our very perceptions” of the latter (p. 170).

2All the courses are taught face-to-face . The categories differ in course length: the first undergraduate degree courses are taught over 4 years with a minimum of 2,800 hours; the second degree is between 2 and 2½ years and between 800 and 1200 hours, both including 400 hours of pedagogic practices. The last one, pedagogic development, is a one-year course with a minimum of 540 hours.

3The places are offered based on the demand from each municipality, however, the number of places requested, and the number of in-service teachers who are willing to attend, means that in certain locations the targets are not fulfilled. According to the PARFOR report the discrepancy between the number of places that are offered and the number of teachers that are enrolled needs to be more accurate.

4The President’s term was from 2011-2014. She was re-elected in late 2014, which gives the program a chance of a longer life.

5Green and yellow are national colours of Brazil.

6The International Congress of the Brazilian Association of English Language and Literature teachers—ABRAPUI, Maceió, 2014, and the Fifth Latin American Conference on Language Teacher Education—CLAFPL, Goiânia, 2014.

7http://www.capes.gov.br/cooperacao-internacional/estados-unidos/certificacao-em-lingua-inglesa.

8For this participation, teachers had to present a TOEFL minimum score of 53 points in the modality Internet Based Test or 153 points in the Computer Based Test mode. The same procedure applies to a candidate who has held the International English Language Test System (IELTS) with a minimum score of 4.5 points.

9The ongoing PhD project of one of the authors of this paper (Carvalho Cruvinel) aims at investigating the perceptions of the participants in this program.

10An English version of the declaration can be found at http://www.un.org/WCAR/durban.pdf.

References

Abreu, D. (2014, November). O programa Inglês sem Fronteiras e a inserção das línguas nas políticas institucionais [The English without Borders Program and the role of languages in institutional policies]. Paper presented at the Fourth ABRAPUI International Congress, Maceió, Brazil.

Azevedo, A. S. (2010). Reconstruindo identidades discursivas de raça na sala de aula de língua estrangeira [Reconstructing discursive race identities in the classroom] (Master’s thesis). Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Ball, S. J. (1994). Educational reform: A critical and post-structural approach. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

Ball, S. J., Maguire, M., & Braun, A. (Eds.). (2012). How schools do policy: Policy enactments in secondary schools. London, UK: Routledge.

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511812507.

Camargo, M. (2012). Atlântico Negro Paiol: como estão sendo conduzidas as questões de raça e etnia nas aulas de língua inglesa? [Atlântico Negro Paiol: How are issues of race and ethnicity being dealt with in English language classes?] (Master’s thesis). Universidade Estadual de Ponta Grossa, Brazil.

CAPES, Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior. (2013). Diretoria de Formação de Professores da Educação Básica: Relatório do Parfor 2009-2013 [Basic Education Teacher Education Division: Parfor Report 2009-2013]. Brasilia, BR: Author. Retrieved from https://www.capes.gov.br/images/stories/download/bolsas/1892014-relatorio-PARFOR.pdf.

English First. (2014). EF EPI: Índice de proficiência em inglês da EF [EF English Proficiency Index]. Retrieved from http://www.ef.com.br/epi/.

Ferreira, A. (2006). Formação de professores de língua inglesa e o preparo para o exercício do letramento crítico em sala de aula em prol das práticas sociais: um olhar acerca de raça/etnia [English language teacher education and the preparation for critical literacy in the classroom supporting social practices: An outlook on race/ethnicity]. Revista Línguas & Letras, 7(12), 171-187.

Ferreira, A. (2007). What has race/ethnicity got to do with EFL teaching? Linguagem & Ensino, 10(1), 211-233.

Ferreira, A. (2009). Histórias de professores de línguas e experiências com o racismo: uma reflexão para a formação de professores [Language teachers’ narratives and experiences with racism: Reflections for teacher education]. Espéculo: Revista de Estudios Literarios, 42. Retrieved from http://www.ucm.es/info/especulo/numero42/racismo.html.

Ferreira, A. (2012). Identidades sociais de raça/etnia na sala de aula de língua inglesa [Identities of race/ethnicity in English language classrooms]. In A. Ferreira (Org.), Identidades sociais de raça, etnia, gênero e sexualidade: práticas pedagógicas em sala de aula de línguas e formação de professores/as (pp. 19-50). Campinas, BR: Pontes Editores.

Ferreira, A. (2014). Teoria racial crítica e letramento racial crítico: narrativas e contranarrativas de identidade racial de professores de línguas [Critical race theory and critical race literacy: Narratives and counternarratives of language teachers]. Revista da ABPN, 6(14), 236-263.

Giddens, A. (1989). Sociology. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Gimenez, T., Calvo, L. C. S., & El Kadri, M. S. (Eds.). (2011). Inglês como língua franca: ensino-aprendizagem e formação de professores [English as a língua franca: Learning-teaching and teacher education]. Campinas, BR: Pontes Editores.

Gimenez, T., & Passoni, T. P. (2014). Competing discourses between English as a Lingua Franca and the “English without Borders” program. Proceedings of the Seventh ELF Conference, Athens, Greece.

Gimenez, T., Serafim, J., & Alonso, T. (2006). O império contra-ataca? A ascensão da língua inglesa a partir da Segunda Guerra Mundial [The empire strikes back? The uprising of the English language after World War II]. Uniletras, 27, 109-122.

Holliday, A. (2011). Intercultural communication and ideology. London, UK: Sage Publications.

Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Aloisio Teixeira. (INEP). (2005). Official website. http://www.inep.gov.br.

Kachru, B. B. (1986). The alchemy of English: The spread, functions and models of non-native Englishes. London, UK: Pergamon.

Kubota, R. (2003). New approaches to gender, class, and race in second language writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 12(1), 31-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1060-3743(02)00125-X.

Liggett, T. (2014). The mapping of a framework: Critical race theory and TESOL. The Urban Review, 46(1), 112-124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-013-0254-5.

Mauranen, A. (2012). Exploring ELF: Academic English shaped by non-native speakers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

McCowan, T. (2013). Education as a Human Right: Principles for a universal entitlement to learning. London, UK: Bloomsbury Academic.

Melo, G. C., Rocha, L. L., & Silva Júnior, P. M. (2013). Raça, gênero e sexualidade interrogando professores (as): perspectivas queer sobre a formação docente [Race, gender and sexuality interrogating teachers: Queer perspectives about teacher education]. Poiésis: Revista do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, 7(12), 237-255.

Ministério da Educação. (MEC). (1998). Parâmetros curriculares nacionais: Área de linguagens e códigos e suas tecnologias. O conhecimento em língua estrangeira moderna [National curriculum parameters: Languages, codes and technologies]. Brasília, BR: Author.

Ministério da Educação. (MEC). (2004). Parecer No. CNE/CP 003/2004 de diretrizes curriculares nacionais para a educação das relações étnico-raciais e para o ensino de história e cultura afro-brasileira e africana [Statement CNE/CP 003/2004 on curriculum guidelines for the education on ethno-racial relations and for the teaching of the Afrobrazilian and African history and culture]. Brasília, BR: Author.

Moita Lopes, L. P. (2002). Identidades fragmentadas: a construção discursiva de raça, gênero e sexualidade em sala de aula [Fragmented identities: The discursive construction of race, gender, and sexuality in the classroom]. Campinas, BR: Mercado de Letras.

Norton, B., & Toohey, K. (2011). Identity, language learning, and social change. Language Teaching, 44(4), 412-446. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444811000309.

Nussbaum, M. C. (2011). Creating capabilities: The human development approach. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674061200.

Nussbaum, M. C., & Sen, A. (Eds.). (1993). The quality of life: Studies in development economics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/0198287976.001.0001.

Park, J. S.-Y., & Wee, L. (2014). Markets of English: Linguistic capital and language policy in a globalizing world. London, UK: Routledge.

Pennycook, A. (2001). Critical applied linguistics: A critical introduction. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Pessoa, R. R. (2014). A critical approach to the teaching of English: Pedagogical and identity engagement. Revista Brasileira de Linguística Aplicada, 14(2), 353-372. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-63982014005000005.

Ricento, T. (Ed). (2015). Language policy and political economy: English in a global context. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199363391.001.0001.

Rubdy, R., & Saraceni, M. (2006). English in the world: Global rules, global roles. London, UK: Continuum.

Santos, J. S. (2011). Raça/etnia, cultura, identidade e o professor na aplicação da Lei no 10639/2003 em aulas de língua inglesa: como? [Race/ethnicity, culture, identity and the teacher in relation to Law No. 10639/2003 in English languag classes: How?] (Master’s thesis). Universidade do Estado da Bahia, Brazil.

Science without Borders. (2014). Motivation. Retrieved from http://www.cienciasemfronteiras.gov.br/web/csf-eng/motivation.

Secretaria da Educação do Estado do Pará. (2014). Official website. http://www.seduc.pa.gov.br.

Seidlhofer, B. (2011). Understanding English as a lingua franca. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Sguissardi, W. (2006). Reforma universitária no Brasil 1995-2006: precária trajetória e incerto futuro [University reform in Brazil 1995-2006: Precarious trajectory and uncertain future]. Educação e Sociedade, 27(96), 1021-1056. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-73302006000300018.

Silva, P. (2009). Reflexões sobre raça e racismo em sala de aula: uma pesquisa com duas professoras de inglês negras [Reflections on race and racism in the classroom: A research with two black English language teachers]. (Master’s thesis). Universidade Federal de Goiás, Brazil.

Urzêda-Freitas, M. T. (2012). Pedagogia como transgressão: problematizando a experiência de professores/as de inglês com o ensino crítico de línguas [Pedagogy as transgression: problematizing the experience of English language teachers with critical language teaching]. (Master’s thesis). Universidade Federal de Goiás, Brazil.

Walker, M., & Unterhalter, E. (2007). Amartya Sen’s capability approach and social justice in education. New York, NY: Palgrave. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230604810.

Widdowson, H. G. (2000). Object language and the language subject: On the mediating role of applied linguistics. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 20, 21-33. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190500200020.

Widdowson, H. G. (2012). ELF and the inconvenience of established concepts. Journal of English as a Lingua Franca, 1(1), 5-26. https://doi.org/10.1515/jelf-2012-0002.

About the Authors

Telma Gimenez is currently Associate Professor at Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Paraná, Brazil, where she teaches Applied Linguistics and English as a lingua franca in the undergraduate degree program and supervises postgraduate research on foreign language teacher education and educational policies. She is a researcher funded by CNPq.

Aparecida de Jesus Ferreira is currently associate professor at UEPG, State University of Ponta Grossa, Paraná, Brazil, where she teaches teaching practice, in the language course for undergraduate students and is a lecturer in the MA course of language, identity, and subjectivity at the same institution.

Rosângela Aparecida Alves Basso is a university researcher at the Department of Modern Foreign Languages at the State University of Maringá, Paraná, Brazil. Her professional interests include language teaching education and development, higher education policies and distance learning.

Roberta Carvalho Cruvinel is an English teacher in Brazilian public schools. She holds a master degree in Applied Linguistics from University of Brasilia and is currently pursuing a PhD degree in Linguistics from Federal University of Goiás and developing part of her research at the Institute of Education, London.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by CAPES—Brazilian Ministry of Education (grants PDSE-4136/2014-04, BEX 9436/13, BEX 4136/14-4, BEX 10758/13-5). We thank Sean Stroud for the language editing of an earlier version of this text.

References

Abreu, D. (2014, November). O programa Inglês sem Fronteiras e a inserção das línguas nas políticas institucionais [The English without Borders Program and the role of languages in institutional policies]. Paper presented at the Fourth ABRAPUI International Congress, Maceió, Brazil.

Azevedo, A. S. (2010). Reconstruindo identidades discursivas de raça na sala de aula de língua estrangeira [Reconstructing discursive race identities in the classroom] (Master’s thesis). Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Ball, S. J. (1994). Educational reform: A critical and post-structural approach. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

Ball, S. J., Maguire, M., & Braun, A. (Eds.). (2012). How schools do policy: Policy enactments in secondary schools. London, UK: Routledge.

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511812507.

Camargo, M. (2012). Atlântico Negro Paiol: como estão sendo conduzidas as questões de raça e etnia nas aulas de língua inglesa? [Atlântico Negro Paiol: How are issues of race and ethnicity being dealt with in English language classes?] (Master’s thesis). Universidade Estadual de Ponta Grossa, Brazil.

CAPES, Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior. (2013). Diretoria de Formação de Professores da Educação Básica: Relatório do Parfor 2009-2013 [Basic Education Teacher Education Division: Parfor Report 2009-2013]. Brasilia, BR: Author. Retrieved from https://www.capes.gov.br/images/stories/download/bolsas/1892014-relatorio-PARFOR.pdf.

English First. (2014). EF EPI: Índice de proficiência em inglês da EF [EF English Proficiency Index]. Retrieved from http://www.ef.com.br/epi/.

Ferreira, A. (2006). Formação de professores de língua inglesa e o preparo para o exercício do letramento crítico em sala de aula em prol das práticas sociais: um olhar acerca de raça/etnia [English language teacher education and the preparation for critical literacy in the classroom supporting social practices: An outlook on race/ethnicity]. Revista Línguas & Letras, 7(12), 171-187.

Ferreira, A. (2007). What has race/ethnicity got to do with EFL teaching? Linguagem & Ensino, 10(1), 211-233.

Ferreira, A. (2009). Histórias de professores de línguas e experiências com o racismo: uma reflexão para a formação de professores [Language teachers’ narratives and experiences with racism: Reflections for teacher education]. Espéculo: Revista de Estudios Literarios, 42. Retrieved from http://www.ucm.es/info/especulo/numero42/racismo.html.

Ferreira, A. (2012). Identidades sociais de raça/etnia na sala de aula de língua inglesa [Identities of race/ethnicity in English language classrooms]. In A. Ferreira (Org.), Identidades sociais de raça, etnia, gênero e sexualidade: práticas pedagógicas em sala de aula de línguas e formação de professores/as (pp. 19-50). Campinas, BR: Pontes Editores.

Ferreira, A. (2014). Teoria racial crítica e letramento racial crítico: narrativas e contranarrativas de identidade racial de professores de línguas [Critical race theory and critical race literacy: Narratives and counternarratives of language teachers]. Revista da ABPN, 6(14), 236-263.

Giddens, A. (1989). Sociology. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Gimenez, T., Calvo, L. C. S., & El Kadri, M. S. (Eds.). (2011). Inglês como língua franca: ensino-aprendizagem e formação de professores [English as a língua franca: Learning-teaching and teacher education]. Campinas, BR: Pontes Editores.

Gimenez, T., & Passoni, T. P. (2014). Competing discourses between English as a Lingua Franca and the “English without Borders” program. Proceedings of the Seventh ELF Conference, Athens, Greece.

Gimenez, T., Serafim, J., & Alonso, T. (2006). O império contra-ataca? A ascensão da língua inglesa a partir da Segunda Guerra Mundial [The empire strikes back? The uprising of the English language after World War II]. Uniletras, 27, 109-122.

Holliday, A. (2011). Intercultural communication and ideology. London, UK: Sage Publications.

Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Aloisio Teixeira. (INEP). (2005). Official website. http://www.inep.gov.br.

Kachru, B. B. (1986). The alchemy of English: The spread, functions and models of non-native Englishes. London, UK: Pergamon.

Kubota, R. (2003). New approaches to gender, class, and race in second language writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 12(1), 31-47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1060-3743(02)00125-X.

Liggett, T. (2014). The mapping of a framework: Critical race theory and TESOL. The Urban Review, 46(1), 112-124. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11256-013-0254-5.

Mauranen, A. (2012). Exploring ELF: Academic English shaped by non-native speakers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

McCowan, T. (2013). Education as a Human Right: Principles for a universal entitlement to learning. London, UK: Bloomsbury Academic.

Melo, G. C., Rocha, L. L., & Silva Júnior, P. M. (2013). Raça, gênero e sexualidade interrogando professores (as): perspectivas queer sobre a formação docente [Race, gender and sexuality interrogating teachers: Queer perspectives about teacher education]. Poiésis: Revista do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, 7(12), 237-255.

Ministério da Educação. (MEC). (1998). Parâmetros curriculares nacionais: Área de linguagens e códigos e suas tecnologias. O conhecimento em língua estrangeira moderna [National curriculum parameters: Languages, codes and technologies]. Brasília, BR: Author.

Ministério da Educação. (MEC). (2004). Parecer No. CNE/CP 003/2004 de diretrizes curriculares nacionais para a educação das relações étnico-raciais e para o ensino de história e cultura afro-brasileira e africana [Statement CNE/CP 003/2004 on curriculum guidelines for the education on ethno-racial relations and for the teaching of the Afrobrazilian and African history and culture]. Brasília, BR: Author.

Moita Lopes, L. P. (2002). Identidades fragmentadas: a construção discursiva de raça, gênero e sexualidade em sala de aula [Fragmented identities: The discursive construction of race, gender, and sexuality in the classroom]. Campinas, BR: Mercado de Letras.

Norton, B., & Toohey, K. (2011). Identity, language learning, and social change. Language Teaching, 44(4), 412-446. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0261444811000309.

Nussbaum, M. C. (2011). Creating capabilities: The human development approach. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674061200.

Nussbaum, M. C., & Sen, A. (Eds.). (1993). The quality of life: Studies in development economics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/0198287976.001.0001.

Park, J. S.-Y., & Wee, L. (2014). Markets of English: Linguistic capital and language policy in a globalizing world. London, UK: Routledge.

Pennycook, A. (2001). Critical applied linguistics: A critical introduction. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Pessoa, R. R. (2014). A critical approach to the teaching of English: Pedagogical and identity engagement. Revista Brasileira de Linguística Aplicada, 14(2), 353-372. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-63982014005000005.

Ricento, T. (Ed). (2015). Language policy and political economy: English in a global context. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199363391.001.0001.

Rubdy, R., & Saraceni, M. (2006). English in the world: Global rules, global roles. London, UK: Continuum.

Santos, J. S. (2011). Raça/etnia, cultura, identidade e o professor na aplicação da Lei no 10639/2003 em aulas de língua inglesa: como? [Race/ethnicity, culture, identity and the teacher in relation to Law No. 10639/2003 in English languag classes: How?] (Master’s thesis). Universidade do Estado da Bahia, Brazil.

Science without Borders. (2014). Motivation. Retrieved from http://www.cienciasemfronteiras.gov.br/web/csf-eng/motivation.

Secretaria da Educação do Estado do Pará. (2014). Official website. http://www.seduc.pa.gov.br.

Seidlhofer, B. (2011). Understanding English as a lingua franca. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Sguissardi, W. (2006). Reforma universitária no Brasil 1995-2006: precária trajetória e incerto futuro [University reform in Brazil 1995-2006: Precarious trajectory and uncertain future]. Educação e Sociedade, 27(96), 1021-1056. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-73302006000300018.

Silva, P. (2009). Reflexões sobre raça e racismo em sala de aula: uma pesquisa com duas professoras de inglês negras [Reflections on race and racism in the classroom: A research with two black English language teachers]. (Master’s thesis). Universidade Federal de Goiás, Brazil.

Urzêda-Freitas, M. T. (2012). Pedagogia como transgressão: problematizando a experiência de professores/as de inglês com o ensino crítico de línguas [Pedagogy as transgression: problematizing the experience of English language teachers with critical language teaching]. (Master’s thesis). Universidade Federal de Goiás, Brazil.

Walker, M., & Unterhalter, E. (2007). Amartya Sen’s capability approach and social justice in education. New York, NY: Palgrave. http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/9780230604810.

Widdowson, H. G. (2000). Object language and the language subject: On the mediating role of applied linguistics. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 20, 21-33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0267190500200020.

Widdowson, H. G. (2012). ELF and the inconvenience of established concepts. Journal of English as a Lingua Franca, 1(1), 5-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/jelf-2012-0002.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Lía D. Kamhi‐Stein, Fabiana Sacchi. (2025). The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of World Englishes. , p.1. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119518297.eowe00314.

2. Kanavillil Rajagopalan. (2020). Functional Variations in English. Multilingual Education. 37, p.167. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52225-4_11.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.