Identifying Pre-Service Teachers’ Beliefs About Teaching EFL and Their Potential Changes

Identificación de creencias de docentes en formación sobre la enseñanza de inglés como lengua extranjera y sus posibles cambios

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n2.59675Keywords:

Beliefs, English as a foreign language, pre-service teachers, teaching practicum (en)creencias, docentes en formación, inglés como lengua extranjera, práctica docente (es)

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n2.59675

Identifying Pre-Service Teachers’ Beliefs About Teaching EFL and Their Potential Changes

Identificación de creencias de docentes en formación sobre la enseñanza de inglés como lengua extranjera y sus posibles cambios

Sergio Andrés Suárez Flórez*

Edwin Arley Basto Basto**

Universidad de Pamplona, Pamplona, Colombia

*sergiom_1447@hotmail.com

**Edwin.basto@unipamplona.edu.co

This article was received on August 19, 2016, and accepted on March 6, 2017.

How to cite this article (APA, 6th ed.):

Suárez Flórez, S. A., & Basto Basto, E. A. (2017). Identifying pre-service teachers’ beliefs about teaching EFL and their potential changes. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 19(2), 167-184. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n2.59675.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This study aims at identifying pre-service teachers’ beliefs about teaching English as a foreign language and tracking their potential changes throughout the teaching practicum. Participants were two pre-service teachers in their fifth year of their Bachelor of Arts in Foreign Languages program in a public university in Colombia. Data were gathered through a modified version of Beliefs about Language Learning Inventory before the practicum, eight weekly journal entries administered during ten weeks, and two semi-structured interviews at the end of the teaching practicum. The findings revealed that most of the pre-service teachers’ beliefs changed once they faced the reality of the classroom.

Key words: Beliefs, English as a foreign language, pre-service teachers, teaching practicum.

Este estudio tiene como objetivo identificar las creencias de los practicantes sobre la enseñanza del inglés como lengua extranjera y hacer un seguimiento a sus posibles cambios durante la práctica docente. Los participantes se encontraban en quinto año del programa de licenciatura en lenguas extranjeras en una universidad pública en Colombia. Los datos fueron recolectados a través de una versión modificada del cuestionario sobre las creencias en el aprendizaje de una lengua antes de la práctica, ocho diarios de reflexión durante diez semanas y dos entrevistas semiestructuradas al final de la práctica docente. Los hallazgos revelaron que la mayoría de las creencias de los participantes cambiaron una vez enfrentaron la realidad del salón de clases.

Palabras clave: creencias, docentes en formación, inglés como lengua extranjera, práctica docente.

Introduction

In Colombia, foreign language (FL) pre-service teachers’ education encompasses five main components: the linguistic, pedagogic, didactic, research, and humanistic elements. The General Law of Education (Law 115, Congreso de la República de Colombia, 1994) recognizes the professionalism of teachers and recommends that they should be committed to their field of study and to their students. Bearing in mind the educational context teachers should decide how and what to teach so that students can reach a proper understanding. In this sense, the education of pre-service teachers does not include only the five components mentioned above but also the teaching formation, aimed at equipping the teachers-to-be with the professional skills needed to put into practice the recommendations given by language polices.

Accordingly, the School of Education at Universidad de Pamplona (Colombia) where this research was conducted has as its mission to educate high-academic level teachers to be agents of change in order to contribute to the education of the new Colombian generation. The Bachelor of Arts program in Foreign Languages, English and French, “enables pre-service teachers to master the essential skills and competences that [will] allow them to tackle the challenges they are likely to face” (Cote, 2012, p. 26) throughout the practicum.1

Additionally, the FL program includes a four-stage preparation in order to provide pre-service teachers with pedagogic competences and teaching formation before entering the teaching practicum. These stages are: (1) peer tutor, in which students from sixth semester assist freshman students in grammar and expose them to university life; (2) teacher assistant, a seventh semester student supports basic teacher tasks within any of the previous six language courses either in English or French; (3) foreign languages course for the community (teacher trainee), an eighth semester student starts the first teaching experience in a real context guiding a course either in English or French; and (4) social work community (service teacher), where the undergraduates put into practice their acquired knowledge, proficiency, and expertise.

After completing the first four teaching stages, we became interested in studying pre-service teachers’ beliefs predicting that they would influence the teaching practicum, and would be valuable for informing teacher educators and shaping teacher preparation programs. Consequently, the current project attempts to make pre-service teachers more aware of the importance of identifying and reflecting on their beliefs.

The purpose of this study was to identify pre-service teachers’ beliefs on teaching English as a foreign language (EFL) and their potential changes during the practicum through a reflective process. Two questions guided this study: (1) What are pre-service teachers’ beliefs regarding teaching English to high school students prior to the teaching practicum? (2) Do pre-service teachers’ beliefs on teaching change during their practicum, and if so, how do they change?

This paper is organized as follows: first it presents the theoretical framework and literature on pre-service teachers’ beliefs. Second, the method and main features of this research are explained. Finally, the findings are presented followed by a conclusion.

Literature Review

This section shows the notions of pre-service teachers’ beliefs and a general overview of studies in the field of reflection and pre-service teachers’ beliefs. It is divided into three categories: Changes in pre-service teachers’ beliefs, the reflective approach, and research on pre-service teachers’ beliefs in Colombia.

Richards and Lockhart (1996) stated that “teachers’ belief systems are founded on the goals, values, and beliefs teachers hold in relation to the content and process of teaching as well as their understanding of the systems in which they work” (p. 42). They also defined beliefs as “the psychologically held understandings, premises, or propositions about the world that are felt to be true” (p. 103). Kagan (1992) defined teachers’ beliefs as “tacit, often unconsciously held assumptions about the students, the classroom, and the academic material to be taught” (p. 65). However, this investigation followed M. Borg’s (2001) definition that complemented Kagan’s by adding that beliefs have also a conscious nature. Having selected this framework allowed us to have a bigger source of beliefs to be identified on the two pre-service teachers in the current investigation.

Changes in Pre-Service Teachers’ Beliefs

Although a change in beliefs has been defined differently (M. Borg, 2001; Calderhead & Robson, 1991; Kagan, 1992), this research adopted the following definition of change which is aligned with this study: “movement or development in beliefs” (Cabaroglu & Roberts as cited in Clark-Goff, 2008, p. 7).

Mattheoudakis (2007) conducted a longitudinal study to investigate 66 pre-service EFL teachers’ beliefs about learning and teaching in Greece during a three-year teacher education program. The author found that through the practicum, the pre-service teachers realized that the classroom reality helped them test their knowledge and become more aware of their personal beliefs about learning and teaching. Moreover, the researcher identified changes in pre-service teachers’ beliefs once they had been exposed to teaching in real contexts. She suggested that pre-service teachers need opportunities for reflection during the teaching practice.

Similarly, Debreli (2012) investigated three pre-service teachers as they changed their beliefs about teaching and learning EFL through a nine-month pre-service teachers’ preparation program. According to the author, the participants’ beliefs changed incrementally once they taught in a real classroom setting. The researcher concluded that “participants’ beliefs changed as a result of the personal teaching experiences they had during the program” (p. 372).

Additionally, Yuan and Lee (2014) investigated the process of beliefs’ change among three pre-service language teachers during the teaching practicum at a university in China. The researchers found that pre-service teachers’ beliefs experienced different processes of change during the practicum, which included confirmation, realization, disagreement, elaboration, integration, and modification. This could be attributed to their situated learning in the school field with the professional culture and expert support. The authors suggested that “opportunities should be provided for pre-service teachers to take part in professional activities in the teaching practicum such as reflective journal writing” (p. 10).

Furthermore, Seymen (2012) explored the relevance of six female pre-service teachers’ beliefs about self and teaching roles to their own teaching practice in schools in Turkey. The findings showed that there were considerable changes regarding pre-service teachers’ perceptions. For example, when starting the investigation, pre-service teachers saw themselves as a guide, someone who helped students in their learning process. However, this belief changed once they started the practicum as the pre-service teachers saw themselves instead as controllers and managers of the classroom.

The previous research studies support the idea that pre-service teachers’ beliefs might be influenced and changed throughout the teaching practice because of several factors such as: being exposed to a real classroom context, facing personal experiences, and changing self-image. Moreover, these studies confirmed the importance of reflecting in the practicum.

The Reflective Approach

Reflection has been defined regarding the improvement of the professional skills in the teaching field. In fact, Schön (as cited in Ahmed & Al-Khalili, 2013) defined reflective teaching as “looking at what teachers do in the classroom, thinking about why they do it and thinking about if it works, a process of self-observation and self-evaluation” (p. 59). Besides, Richards and Lockhart (1996) stated that a reflective approach to teaching is one in which “teachers and student-teachers collect data about teaching, examine their attitudes, beliefs, assumptions, and teaching practices and use the information obtained as a basis for critical reflection about teaching” (p. 1). Moreover, Dewey (1933) defined reflection as a “state of doubt, hesitation, perplexity, mental difficulty in which thinking originates an act of searching, hunting, and inquiring to find material that will resolve the doubt and dispose of the perplexity” (p. 12). However, our study followed McLean’s (2007) definition from a teacher perspective in which reflection “involves thinking about and critically analyzing our experiences and actions, and those of our students, with the goal of improving our professional practice” (p. 5.9). This definition allowed us to understand the intersection of reflection and teaching.

Reflection has been used to identify the sources of teachers’ beliefs and their benefits in the teaching practice. Abdullah and Majid (2012) conducted a study to investigate teachers’ beliefs in Malaysia. The researchers found that there were four potential sources of beliefs identified throughout a reflection process: experience as learners, perception towards students, institutional environment or practice, and personal views on current practice.

Likewise, some scholars have found benefits from the reflection process in the teaching practicum. For instance, Sikka and Timoštšuk (2008) investigated 45 students in Estonia to identify the changes and transformations from student to teacher at their practicum. They found that the reflection process allowed pre-service teachers to learn to see their weaknesses and be able to work on them and establish goals for further development.

Additionally, Ahmed and Al-Khalili (2013) conducted a case study at a public university in Egypt with 25 primary science pre-service teachers. The researchers found that reflective teaching helped participants to identify strengths and weaknesses in teaching. This process enabled them “to analyze, discuss, evaluate, and change their own practice as well as to adopt a systematic analytical approach towards teaching” (p. 63).

Similarly, Farrell (1999) conducted a study in order to understand five pre-service teachers’ beliefs when teaching grammar in Singapore. He found that the reflective process allowed participants to be more aware of their past influences, as they considered themselves to be learners as well. He stated that the experiences as learners and the current one of teaching might be a powerful method of shaping their own development as teachers.

Recently, reflection has been implemented as a process to explore critical incidents when teaching. For example, Lengeling and Mora Pablo (2016) conducted a study with eight beginner teachers at a public university in Mexico. Findings revealed that critical incidents helped teachers to “shape their attitudes and perceptions at a given time in their lives” (p. 86). According to the authors, incidents provoke reflection of common events but in reality they are more powerful because of what is learnt. Finally, the authors stated that these reflections might allow teachers to analyze their values, beliefs, and perceptions.

At the university where this study took place, two investigations have been conducted regarding the pre-service teachers’ reflective process during the practicum. Camacho et al. (2012) attempted to understand how a process of reflection helped five foreign language pre-service teachers throughout the practicum. The researchers found that reflection gave participants the opportunity to analyze their actions and how they might have thought of changing their way of teaching. Additionally, they found that the act of reflecting is directly linked to the circumstances or events during the classroom practicum.

Likewise, Cote (2012) conducted an exploratory case study with four pre-service teachers at two public high schools, one private school, and one public university in Colombia. The researcher found that the reflection process allowed the pre-service teachers to improve their practice teaching and helped them to implement necessary changes with the aim of improving their teaching.

These findings confirmed the applicability of reflection as a process to identify pre-service teachers’ changes in beliefs. Besides, this instrument might allow student-teachers to learn from their personal experiences in order to improve their teaching practice.

Research on Pre-Service Teachers’ Beliefs in Colombia

In Colombia, there has been a growing interest in studying pre-service teachers’ beliefs based on their self-image, perceptions, and past experiences as learners in the teaching practice.

Castellanos (as cited in Castellanos, 2013) focused her study on pre-service English teachers’ construction of self-image as teachers. Her findings showed that there were three crucial factors that constructed pre-service teachers’ self-image: the identification of past teachers, the interaction and collaboration with other teachers, and their systems of beliefs about learning and teaching. The author also found that “change in pre-service teachers’ perception of themselves as language teachers was fostered by making connections between their knowledge base, practice and by being faced with difficult situations that posed challenges to their belief system” (pp. 201-202).

Likewise, Samacá (as cited in Castellanos, 2013) conducted a study with the purpose of understanding the influence of 13 pre-service teachers’ perceptions regarding their future image as teachers while teaching in a university in Colombia. Findings revealed that “there were three important aspects for the construction of student-teachers’ image as future teachers: a dialogical relationship between students and teachers, the instructional roles they are to develop in their classroom settings, and models to be or not to be followed” (p. 202).

The professional identity of student teachers’ beliefs has been also studied. For example, Fajardo (2014) studied the transformation of pre-service teachers’ professional identity. The author explored how six pre-service teachers constructed the meaning of becoming a teacher during the last stage of the teacher preparation at a public university in Colombia. The researcher found that the relationship between beliefs and classroom practice constructed, formed, and transformed pre-service teachers’ identity. However, this construction might have been limited since they were permanently supervised during the teaching practice, which might have restricted their free development in the classroom.

Furthermore, Gutiérrez (2015) investigated the influence of beliefs throughout the teaching practice. The author investigated three pre-service teachers from a language program preparation in Medellín, Colombia. The purpose of this study was to understand “how pre-service teachers responded to the exploration of critical literacy theories, beliefs, and reflections while designing and implementing critical-literacy based lessons” (p. 191). The researcher found that “participants’ beliefs, attitudes, and reflections were transformed throughout the study” (p. 191). Additionally, the author found that participants believed that changing the education system in Colombia would be difficult because there are certain challenges: the ages of the learners since they believed that the students were not prepared to be part of critical discussions and, the acknowledgment of learners’ parents in terms of discussing specific topics like politics and sexuality.

It is important to highlight that although there is a growing interest to investigate pre-service teachers’ beliefs in Colombia, it is still limited.

Method

This investigation adopted an intrinsic case study which allowed us to reach a comprehensive understanding of a particular case using a variety of data gathering techniques and methods of analysis. Creswell (2007) stated that “we conduct qualitative research because we need a complex and detailed understanding of the issue” (p. 40). This investigation was framed under a naturalistic approach in order to study participants in their natural settings.

The sampling process started by inviting eight potential participants who were about to start the practicum to take part in a lecture in which we explained this study in detail. Once they were informed about the main features of the study, four pre-service teachers decided to take part in the project. However, due to different circumstances, only two pre-service teachers consented to take part in it.

They were two female undergraduate pre-service teachers in the FL program at Universidad de Pamplona in Colombia. They did their practicum in two public high schools, and their language proficiency ranged between B1 and B2. Although they were in charge of two seventh-grade courses, they were asked to keep a reflective journal in only one of the courses. Each course had from 30 to 35 students where in each class they were organized into different rows. Their ages ranged from 11 to 13 years old. The teachers’ practicum involved 12 weekly hours of teaching for the duration of ten weeks. The pre-service teachers also signed a letter of consent that fully explained their responsibilities and rights as participants.

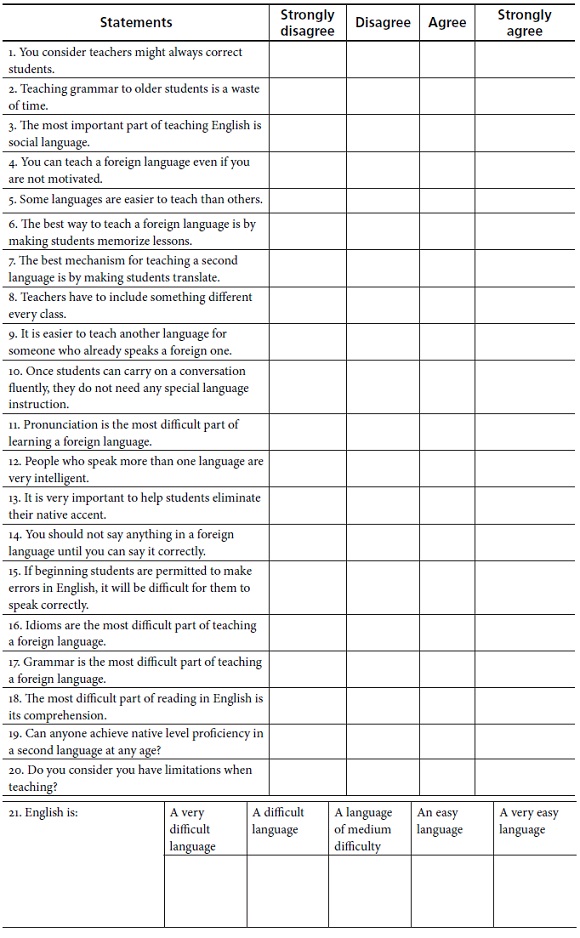

This study was divided into three phases. In the first phase, before starting the teaching practice, we provided a questionnaire to identify pre-service teachers’ beliefs. The questionnaire was adapted from the Beliefs about Language Learning Inventory (BALLI) developed by Horwitz (1987). The BALLI is a quantitative self-report questionnaire designed to investigate 34 learners’ beliefs. It is organized into five categories: the difficulty of language learning, foreign language aptitude, the nature of language learning, learning communication strategies, and motivation and expectations.

However, we organized the BALLI2 into 21 items (see Appendix A) about teaching. For each item participants were required to indicate whether they (1) strongly disagree, (2) disagree, (3) agree, or (4) strongly agree. We also administered two open ended questions: What are your limitations at present when teaching? And do you consider that eliminating obstacles can help you in the teaching process? This questionnaire was provided to participants in English.

During the second phase, the pre-service teachers were asked to answer a weekly reflective journal during 10 weeks of their practicum. The journal was adapted from the reflective questions3 (see Appendix B) to guide journal entries developed by Richards and Lockhart (1996).4 These questions were sent via e-mail in Spanish in order to allow participants to express and describe their experiences in their mother tongue. As we attempted to track changes in pre-service teachers’ beliefs, asking participants about the difficulties, changes, and challenges they dealt with throughout their practicum was vital for the purpose of the study.

In the final phase, two semi-structured interviews (see Appendix C)5 were carried out with the purpose of complementing the data gathered once the pre-service teachers concluded their practicum. The questions were based on the assessment of the information participants provided through the journals. Participants were interviewed separately for 20 minutes. The interview was conducted in Spanish and the data were recorded and transcribed.

The data collected from each participant were analyzed separately following Hatch’s (2002) inductive and interpretive models of qualitative data analysis, which suggested that “using interpretive technique will make studies richer and findings more convincing when interpretive analytic processes are used along with or in addition to inductive analyses” (p. 181). First, all the recorded interviews and journals were transcribed and translated into English before being organized into a matrix to better visualize the participants’ responses. Additionally, we used the MAXQDA software in order to organize, code, and analyze the data of each participant as part of the procedures established by the models. Once data from each participant were analyzed separately, we did a cross-case analysis that allowed us to identify similarities and differences in pre-service teachers’ beliefs about teaching and their changes.

Findings

This section describes findings and places them into two broad categories: Pre-Service Teachers’ Beliefs and Changes in Pre-Service Teachers’ Beliefs About Teaching.

Pre-Service Teachers’ Beliefs

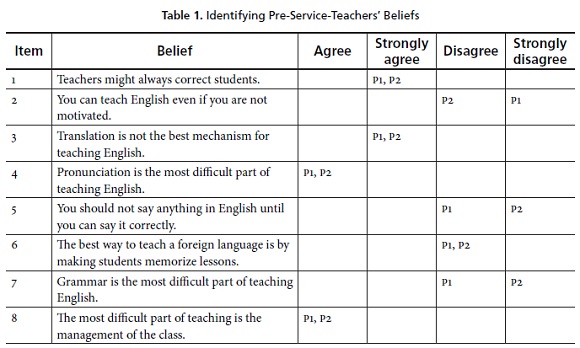

The instruments used before and during the teaching practice indicated that the pre-service teachers held common beliefs (see Table 1) about teaching.

Participants believed that teachers always have to correct students’ productions. The source of this belief might have been their past learning experiences. In fact, one of the participants stated in the journals that when she started studying foreign languages at the Universidad de Pamplona, one of her English teachers did not correct her mispronunciation of some words. Consequently, she pronounced these words incorrectly for several years. More importantly, she started to believe that errors should be corrected immediately.

Similarly, the pre-service teachers expressed their inability to teach English if they were not motivated. Although the participants did not express what motivated them, they often highlighted that their own feelings were an important aspect when teaching English.

Among the ways to teach English, as demonstrated by the BALLI, the pre-service teachers believed that neither translation nor memorization was the best method for teaching English.

In addition to the teaching method, the pre-service teachers expressed their beliefs regarding the potential difficulties of teaching a second language. They believed that while grammar was the least difficult part of teaching English, pronunciation was the most difficult.

The pre-service teachers also held strong beliefs with regard to the development of the class. Before the practicum, they believed their only difficulties would be regarding the management of the class. According to them, this belief is result of the lack of a specific course in the teaching preparation program to address this challenge.

Changes in Pre-Service Teachers’ Beliefs About Teaching

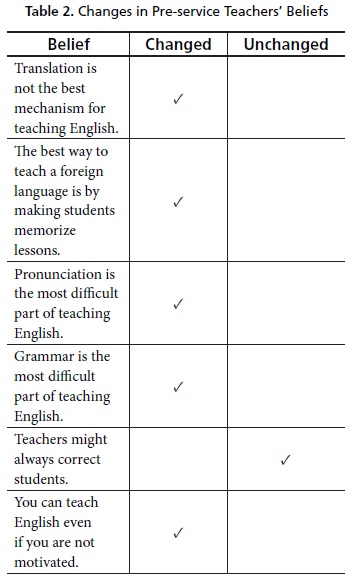

In order to shed light on potential changes of the participants’ five most salient beliefs, we provide an analysis and a thorough description of what the pre-service teachers’ beliefs were like before the teaching practicum and how they changed. They include beliefs about: error correction, teaching mechanism, teaching pronunciation, teaching grammar, and motivation. The findings revealed that 84% of pre-service teachers’ beliefs changed and 16% remained unchanged (see Table 2).

Beliefs About Error Correction

Consistent with their beliefs, the pre-service teachers always sought a suitable error correction technique: they believed that teachers must always correct students’ mistakes. This belief remained unchanged during the practicum. Their conviction was evidenced while they implemented three different correction techniques as the students completed writing and speaking tasks.

First, when the students started working on written exercises, the pre-service teachers walked around the classroom to monitor what they were doing. When they found a mistake on the students’ part, they corrected it immediately. They not only highlighted the wrong word but also explained the reasons behind the mistake in order to develop students’ ability to self-correct their mistakes; as Participant 2 stated:

Regarding the written corrections, I not only marked the mistake with an X but also highlighted it. For example, if it was a verb, I highlighted it and wrote why it was wrong so as to allow the student to learn the correct form of it. (Interview 1)

Second, Participant 1, when doing written activities in pairs, started to find mistakes in the students’ production. However, she asked them to assess their own elaboration asking them immediately: “Are you sure? Is this the correct word?” According to her, this technique allowed the learners to check their production by identifying their own mistakes. However, she realized that this technique was time consuming:

At the beginning of the practicum, I conducted written productions in pairs. While they were working, I tried to read what they were writing. Once I identified a mistake, I asked the students if they should write a [particular] word instead of another one. But, I spent too much time correcting in this way. (Interview 1)

Consequently, Participant 1 changed the type of correction because of the lack of time. She realized that immediately giving the students the correct word was not as time consuming as letting them review their work.

Third, Participant 1 asked the learners to work individually because she had no time to identify their mistakes. Then, she went on trying out another error correction strategy, as she explained:

I realized that the best way to work on written productions was individually because when [they were] working in pairs, I was not able to determine or to identify which student was making the mistake, if it was student A or student B. Then, since the fourth or fifth week, I decided to conduct writing activities on an individual basis. (Interview 2)

Using different error correction strategies helped them to realize a twofold purpose: the pre-service teachers developed the best strategies to correct students’ written productions and the learners became aware of their own mistakes.

Beliefs About the Teaching Mechanisms

Before the teaching practice, the pre-service teachers affirmed that neither memorization nor translation was the best method to teach a foreign language. However, the pre-service-teachers included these two techniques in the teaching practice with different purposes. This belief changed because it was easier to teach English using the learners’ mother tongue since the students understood the topic more easily. They also affirmed that teaching vocabulary was easier when the learners memorized the words.

During the teaching practicum, the pre-service teachers used translation to facilitate the students to learn a new topic. They stated that it was easier to help the students understand the explanation by translating the unknown words. According to Participant 2, translating some words or phrases was a way to motivate the students to learn English since they were able to understand the explanation:

When I was explaining the past tense of the verb to be in English, I noticed that the students did not understand. Consequently, I decided to write some key words in English with their meaning in Spanish related to the explanation. However, most of the time I had to translate long sentences. (Journal 4)

Participants explained the reasons for including translation to facilitate students’ understanding. For example, Participant 2 pointed out that including translation as a teaching tool during the teaching practice allowed her to realize that when working with beginner students, it was sometimes necessary to translate phrases to explain a topic.

When working with students that begin from cero, I wanted to help them reaching at least an A1 English proficiency level. For that reason, it was necessary to use sometimes the mother tongue and translation to explain grammar and answer doubts. (Journal 4)

Additionally, participants taught vocabulary through repetition and memorization. Participant 1 used repetition to facilitate the students’ learning by heart the vocabulary of the lesson, as she stated:

The next class I decided to use flashcards to teach the animals’ vocabulary. Some flashcards had their names on it and other ones did not. I showed the flashcard and the students had to repeat three times the word. Then, I showed the flashcard without the word and the students had to say the name of the animal. At the end, I showed all the flashcards and the students had to pronounce them one by one. (Interview 2)

Participant 2 used memorization to help students grasp grammatical structures more efficiently as shown below:

However, depending on the topic you are explaining, sometimes it is necessary to implement memorization in class. For example, when explaining grammar aspects with students that are starting to learn a foreign language, they have to learn by heart those structures that are the base of what they will use daily. (Journal 4)

In short, translation, memorization, and repetition were used simultaneously to facilitate students’ understanding and internalization of new words and unknown structures.

Beliefs About Teaching Pronunciation

The pre-service teachers used to believe that teaching pronunciation was the most difficult part of teaching a foreign language. However, this belief changed when they used a three-step sequence to teach pronunciation during the practicum.

Throughout the practicum, the pre-service teachers structured the teaching pronunciation process into three steps. First, they showed the writing of the word to be taught with its meaning in the native language and the learners had to repeat it. Second, they pointed at a flashcard and the students had to pronounce the word in English. Third, participants used the flashcards in different activities where the students had to guess the missing word and the word order, as Participant 1 affirmed:

The pronunciation process was divided into two parts: In the first one, I pointed at the writing of an animal’s word with its meaning in Spanish and I pronounced it twice. In the second part, I pointed [at] the flashcard and its writing and the students had to pronounce it. (Interview 2)

In several cases, while Participant 1 was working on pronunciation, she asked each row of students to pronounce a word in unison until they said it correctly. When the pre-service teacher heard that one student mispronounced a word, she immediately asked him to repeat after her and to pronounce it several times from his seat until he could say it correctly. In several instances, the pre-service teachers modeled the tongue positioning to show their students how to pronounce a word correctly, as Participant 2 explained:

I divided the pronunciation process by rows of eight students and worked with them until I heard they pronounced the word correctly, and if I identified that one of them mispronounced the word, I asked only that student to pronounce the word until he was able to. (Interview 2)

On the other hand, Participant 2 was concerned about some difficulties when teaching pronunciation. She realized that the students’ past learning experiences affected their pronunciation learning process. Besides, she stated that this process was more difficult because they mispronounced basic words that were necessary for developing an oral production as she reported:

When I was going to work on pronunciation, I faced some difficulties because in many cases all the students pronounced a word incorrectly and I noted that it was because of their past teachers. (Journal 5)

Consequently, she had to take some minutes of the lesson to teach students the correct pronunciation because according to her, she wanted to avoid students’ fossilization.

Beliefs About Teaching Grammar

The pre-service teachers used to believe that teaching grammar was not the most difficult part when teaching. However, this belief changed during the teaching practicum. Teachers experienced some difficulties that made them have second thoughts about teaching grammar.

Before their teaching practice, the pre-service-teachers observed a class conducted by the cooperating teacher. Once they started the teaching practice, they experienced some difficulties regarding the previous grammar explanations. Participant 1 noticed that it was easier to explain a new grammar structure for those students who had previously mastered the topic. However, most of the students did not remember much of what they had been taught.

The main difficulty was that many students did not remember the verb to be in the present tense. Consequently, I had to give a brief explanation of it. After that, I was able to explain the new grammar structure, the verb to be in past tense. (Journal 7)

Consequently, she had to take some minutes of the class to explain the previous topic again in order to facilitate the students’ current learning process.

Another factor that made the teaching of grammar more challenging was the students’ misbehavior. Once, when Participant 2 was teaching grammar, she decided to use a video to explain a grammar topic. However, she noticed that the students did not take advantage of the technological tool.

In this class, I showed the students a video to allow them understand the grammar topic better, but most of them did not pay attention. (Journal 3)

On the contrary, Participant 1 noticed that most of her students favored visual learning; then, she used visual material as a tool to introduce a new grammar topic. As a result of this practice, she raised the students’ interest in learning a foreign language.

In this lesson, I used a PowerPoint presentation to explain grammar. That was something I changed since I usually use this material just to introduce the vocabulary and only explain grammar on the board. However, I think it was successful because the students wrote several examples using there is/are in their notebooks and participated in class. (Journal 3)

Beliefs About Motivation

Before the teaching practice, the pre-service teachers believed that they would not be able to teach English if they were not motivated. Throughout the practicum, they faced different experiences that made them feel demotivated while teaching. This belief changed because of the dedication they showed when teaching.

During the teaching practice, participants faced some challenges dealing with the students’ attitudes in class. They realized that some students did not value the work and the material they brought every class. According to Participant 1, she felt upset due to the students’ disinterest in taking part in the class activities. She explained, that:

It was a little bit frustrating to see that some students started to break things, stand up every time, or throw the guides away. And, seeing that they come to the school only to play and not to learn was also frustrating. (Journal 2)

Nevertheless, as she once reflected in her journal, she was able to continue the lesson because of the passion she felt when teaching English.

Additionally, Participant 2 felt demotivation when explaining a topic because of the students’ interruptions and their lack of interest. However, she was able to continue the lesson because of the cooperating teachers’ mediation.

As I did not know what to do to continue with the lesson, my supervisor advised me to give the students a low grade for their work in class, and I did. When the students knew that I gave them no grade (0), they started to behave. (Interview 1)

In sum, there were notable changes in the participants’ beliefs when entering a real classroom setting. The changes in beliefs originated partly due to the participants’ previous experiences as learners; and the difficulties and emotions the pre-service teachers faced during the practicum.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study sets out to identify pre-service teachers’ beliefs before the teaching practice with the aim of finding out how they change during this final step of the preparation program. It is difficult to establish whether the beliefs that the pre-service teachers held when starting this study existed before starting the teaching program or, perhaps, the teachers were influenced and shaped throughout the years of preparation. However, this study found that the pre-service teachers started the practicum with several common beliefs about teaching English. For example, the relevance of correcting students’ mistakes, the importance of grammar and pronunciation teaching, the use of translation and memorization, and the influence of motivation during their practicum.

The participants’ past experiences as foreign-language learners influenced their beliefs prior to starting their teaching practicum. The relationship between pre-service teaching expectations and teaching programs has already been documented in the literature. Most pre-service teachers start the teaching practice with expectations as a direct result of the beliefs developed in the pre-service teacher formation program (Coles & Knowles, 1993). This idea is in line with Horwitz’s (1985) study, in which she found that most pre-service teachers’ beliefs are developed while teaching in real classroom settings. In doing so, the pre-service teachers had the chance to test their expectations and shape their beliefs before the practicum.

On the other hand, the findings revealed that most of pre-service teachers’ beliefs changed; a few of them remained unchanged. Table 2 shows a significant difference between the beginning and the end of the practicum. Pre-service teachers’ beliefs were open to change during the practicum; this aligns with S. Borg’s (2006) argument indicating that changes in pre-service teachers’ beliefs take place during this period. In other words, practices lead to belief changes due to the fact that pre-service teachers have not developed teaching routines. However, some scholars argued that the teaching practice is not influential in pre-service teachers’ beliefs (Gutiérrez, 2015; Peacock, 2001). Gutiérrez’s study contrasts our finding indicating that pre-service teachers’ beliefs are stable because they “acquired some teaching experience prior to their practicum” (p. 190), which allowed them to sustain their beliefs on teaching from the beginning to the end.

Before starting the practicum, participants believed that memorization was not the best mechanism; this belief changed when the pre-service teachers included this strategy to facilitate students’ pronunciation, grammar, and vocabulary learning. It was customary for the pre-service teachers to use flashcards to facilitate the memorization of the right pronunciation of several words. Similar findings are found in Alqahtani (2015), who argued that introducing a new word by showing an object helped students to memorize the word. With regard to translation, the participants changed their belief that translation was not the best mechanism for teaching English. While facing the reality of the classroom, they introduced translation to facilitate students’ understanding of grammar and vocabulary.

Another sign of belief change included challenges participants experienced, which were discovered through the reflection journal. Before starting the teaching practice, they believed that pronunciation was not the most difficult part of teaching English. However, along their practicum, they identified that their students’ past learning and misbehavior made them change this belief. Similarly, Gilakjani and Ahmadi (2011) also found that pronunciation is the most difficult part for teachers to address in the classroom. Their study corroborates our finding which indicates that teaching pronunciation is more than simply correcting single sounds or isolated words.

Finally, it is also important to note that the belief about error correction did not change during the practicum. Although the pre-service teachers changed the correction techniques from peer-correction to self-correction as a strategy to develop students’ autonomy, this belief remained unchanged. Participants still assigned a high priority to error correction in class. The teachers realized that they should continue correcting students’ mistakes; however, they also discovered the peer-correction technique to be inadequate.

This study suggests that pre-service teachers should gain teaching experience prior to the practicum so that they will be better prepared once they face the reality of a classroom. Hopefully, the superior foreign language programs should provide pre-service teachers with more classroom teaching experiences and, in turn, they will be better equipped to handle the classroom and become more effective teachers. We also suggest that more growth opportunities, such as assisted reflection, will allow pre-service teachers to improve their teaching abilities and overcome the potential difficulties they experience in this process.

Further research can analyze in greater depth the differences and similarities in pre-service teachers’ and in-service teachers’ beliefs about teaching English and see how they influence their decision making process.

1In this article, teaching practice, teaching practicum, and practicum are used interchangeably.

2Horwitz granted the permission to modify the BALLI.

3However, the researchers sent different questions based on the participants’ answers.

4We obtained the permission to modify it in accordance with the purpose of the study.

5Original questions in Spanish.

References

Abdullah, S., & Majid, F. A. (2012). Reflection on language teaching practice in polytechnic: Identifying sources of teachers’ beliefs. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 90, 813-822. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.07.156.

Ahmed, E. W., & Al-Khalili, K. Y. (2013). The impact of using [a] reflective teaching approach on developing teaching skills of primary science student teachers. The Online Journal of New Horizons in Education, 3(2), 58-64.

Alqahtani, M. (2015). The importance of vocabulary in language learning and how to be taught. International Journal of Teaching and Education, 3(3), 21-34. http://doi.org/10.20472/TE.2015.3.3.002.

Borg, M. (2001). Teachers’ beliefs. ELT Journal, 55(2), 186-188.

Borg, S. (2006). Teacher cognition and language education: Research and practice. London, UK: Continuum.

Calderhead, J., & Robson, M. (1991). Images of teaching: Student teachers’ early conceptions of classroom practice. Teaching and Teacher Education, 7(1), 1-8. http://doi.org/10.1016/0742-051X(91)90053-R.

Camacho, D. Z., Durán, L., Albarracin, J. C., Arciniegas, M. V., Martínez, M., & Cote, G. E. (2012). How can a process of reflection enhance teacher-trainees’ practicum experience? HOW, 19, 48-60.

Castellanos, J. (2013). The role of English pre-service teachers’ beliefs about teaching in teacher education programs. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 15(1), 195-206.

Clark-Goff, K. (2008). Exploring change in pre-service teachers’ beliefs about English language learning and teaching (Doctoral dissertation). Texas A&M University, USA.

Cole, A. L., & Knowles, J. G. (1993). Teacher development partnership research: A focus on methods and issues. American Educational Research Journal, 30(3),473-495. http://doi.org/10.3102/00028312030003473.

Congreso de la República de Colombia. (1994). Ley 115 de febrero 8 de 1994. Retrieved from http://www.mineducacion.gov.co/1621/articles-85906_archivo_pdf.pdf.

Cote, G. (2012). The role of reflection during the first teaching experience of foreign language pre-service teachers: An exploratory-case study. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 14(2), 24-34. http://doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2012.2.a02.

Creswell, J. W. (2007) Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, US: Sage Publications.

Debreli, E. (2012). Change in beliefs of pre-service teachers about teaching and learning English as a foreign language throughout an undergraduate pre-service teacher training program. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 367-373. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.124.

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. Washington D.C.: Heath and Company.

Fajardo, J. A. (2014). Learning to teach and professional identity: Images of personal and professional recognition. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 16(2), 49-65. http://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v16n2.38075.

Farrell, T. S. C. (1999). The reflective assignment: Unlocking pre-service teachers’ beliefs on grammar teaching. RELC Journal, 30(2), 1-17. http://doi.org/10.1177/003368829903000201.

Gilakjani, A. P., & Ahmadi, M. R. (2011). Why is pronunciation so difficult to learn? English Language Teaching, 4(3), 74-83. http://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v4n3p74.

Gutiérrez, C. P. (2015). Beliefs, attitudes, and reflections of EFL pre-service teachers while exploring critical literacy theories to prepare and implement critical lessons. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 17(2), 179-192. http://doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2015.2.a01.

Hatch, J. A. (2002). Doing qualitative research in education settings. Albany, US: State University of New York Press.

Horwitz, E. K. (1985). Using student beliefs about language learning and teaching in the foreign language methods course. Foreign Language Annals, 18(4), 333-340. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.1985.tb01811.x.

Horwitz, E. K. (1987). Surveying student beliefs about language learning. In A. L. Wenden & J. Rubin (Eds.), Learner strategies in language learning (pp. 119-129). London, UK: Prentice-Hall.

Kagan, D. M. (1992). Implications of research on teacher belief. Educational Psychologist, 27(1), 65-90. http://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep2701_6.

Lengeling, M. M., & Mora Pablo, I. (2016). Reflections on critical incidents of EFL teachers during career entry in Central Mexico. HOW, 23(2), 75-88. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.23.2.158.

Mattheoudakis, M. (2007). Tracking changes in pre-service EFL Teacher beliefs in Greece: A longitudinal study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(8), 1272-1288. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.06.001.

McLean, J. (2007). Reflecting on your teaching. In E. Friesen (Ed.), Teaching at the University of Manitoba: A handbook (pp. 5.9-5.12). Winnipeg, CA: University Teaching Services.

Peacock, M. (2001). Pre-service ESL teachers’ beliefs about second language learning: A longitudinal study. System, 29(2), 177-195. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(01)00010-0.

Richards, J. C., & Lockhart, C. (1996). Reflective teaching in second language classrooms. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Seymen, S. (2012). Beliefs and expectations of student teachers about their self and role as teacher during teaching practice course. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 1042-1046. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.245.

Sikka, H., & Timoštšuk, I. (2008). The role of reflection in understanding teaching practice. Problems of Education in the 21st Century, 7, 147-152.

Yuan, R., & Lee, I. (2014). Pre-service teachers’ changing beliefs in the teaching practicum: Three cases in an EFL context. System, 44, 1-12. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2014.02.002.

About the Authors

Sergio Andrés Suárez Flórez is an undergraduate student in the Bachelor of Arts program in foreign languages at Universidad de Pamplona, Colombia. He has participated in three congresses in the EFL educational field in Colombia as speaker and participant.

Edwin Arley Basto Basto is an undergraduate student in the Bachelor of Arts program in foreign languages at Universidad de Pamplona, Colombia. His research interests focus on pre-service teachers’ development during the practicum.

Appendix A: Beliefs About Language Learning Inventory (BALLI)

Appendix B: Sample of Reflective Questions

- What are your limitations at present as a teacher?

- What problems did you have with the lesson?

- What changes do you think you should make in your teaching?

- What do you think students really learned from the lesson?

- Which parts of the lesson were most successful? Explain.

- Which parts of the lesson were least successful? Explain.

- Did you do anything differently than usual?

- What skills did you favor when teaching?

- What is the most important aspect when teaching?

Adapted from Richards and Lockhart (1996)

Appendix C: Semi-Structured Interview Sample

Error correction

Which skill did you correct the most during the practicum?

What is the role of correction?

How did you correct the students’ mistakes?

When did you correct the students’ mistakes?

Teaching material

What type of material did you use during the practicum?

Did you change the materials used, if so, how/why?

What were the students’ reactions towards the new material?

Other questions asked

How did you use the mother tongue in class? Why?

Generally speaking, how many times did you explain grammatical structures?

How did you explain grammar?

What was the most difficult part of teaching grammar?

What was the most important change while teaching?

References

Abdullah, S., & Majid, F. A. (2012). Reflection on language teaching practice in polytechnic: Identifying sources of teachers’ beliefs. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 90, 813-822. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.07.156.

Ahmed, E. W., & Al-Khalili, K. Y. (2013). The impact of using [a] reflective teaching approach on developing teaching skills of primary science student teachers. The Online Journal of New Horizons in Education, 3(2), 58-64.

Alqahtani, M. (2015). The importance of vocabulary in language learning and how to be taught. International Journal of Teaching and Education, 3(3), 21-34. http://doi.org/10.20472/TE.2015.3.3.002.

Borg, M. (2001). Teachers’ beliefs. ELT Journal, 55(2), 186-188.

Borg, S. (2006). Teacher cognition and language education: Research and practice. London, UK: Continuum.

Calderhead, J., & Robson, M. (1991). Images of teaching: Student teachers’ early conceptions of classroom practice. Teaching and Teacher Education, 7(1), 1-8. http://doi.org/10.1016/0742-051X(91)90053-R.

Camacho, D. Z., Durán, L., Albarracin, J. C., Arciniegas, M. V., Martínez, M., & Cote, G. E. (2012). How can a process of reflection enhance teacher-trainees’ practicum experience? HOW, 19, 48-60.

Castellanos, J. (2013). The role of English pre-service teachers’ beliefs about teaching in teacher education programs. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 15(1), 195-206.

Clark-Goff, K. (2008). Exploring change in pre-service teachers’ beliefs about English language learning and teaching (Doctoral dissertation). Texas A&M University, USA.

Cole, A. L., & Knowles, J. G. (1993). Teacher development partnership research: A focus on methods and issues. American Educational Research Journal, 30(3),473-495. http://doi.org/10.3102/00028312030003473.

Congreso de la República de Colombia. (1994). Ley 115 de febrero 8 de 1994. Retrieved from http://www.mineducacion.gov.co/1621/articles-85906_archivo_pdf.pdf.

Cote, G. (2012). The role of reflection during the first teaching experience of foreign language pre-service teachers: An exploratory-case study. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 14(2), 24-34. http://doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2012.2.a02.

Creswell, J. W. (2007) Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, US: Sage Publications.

Debreli, E. (2012). Change in beliefs of pre-service teachers about teaching and learning English as a foreign language throughout an undergraduate pre-service teacher training program. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 367-373. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.124.

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. Washington D.C.: Heath and Company.

Fajardo, J. A. (2014). Learning to teach and professional identity: Images of personal and professional recognition. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 16(2), 49-65. http://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v16n2.38075.

Farrell, T. S. C. (1999). The reflective assignment: Unlocking pre-service teachers’ beliefs on grammar teaching. RELC Journal, 30(2), 1-17. http://doi.org/10.1177/003368829903000201.

Gilakjani, A. P., & Ahmadi, M. R. (2011). Why is pronunciation so difficult to learn? English Language Teaching, 4(3), 74-83. http://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v4n3p74.

Gutiérrez, C. P. (2015). Beliefs, attitudes, and reflections of EFL pre-service teachers while exploring critical literacy theories to prepare and implement critical lessons. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 17(2), 179-192. http://doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2015.2.a01.

Hatch, J. A. (2002). Doing qualitative research in education settings. Albany, US: State University of New York Press.

Horwitz, E. K. (1985). Using student beliefs about language learning and teaching in the foreign language methods course. Foreign Language Annals, 18(4), 333-340. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.1985.tb01811.x.

Horwitz, E. K. (1987). Surveying student beliefs about language learning. In A. L. Wenden & J. Rubin (Eds.), Learner strategies in language learning (pp. 119-129). London, UK: Prentice-Hall.

Kagan, D. M. (1992). Implications of research on teacher belief. Educational Psychologist, 27(1), 65-90. http://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep2701_6.

Lengeling, M. M., & Mora Pablo, I. (2016). Reflections on critical incidents of EFL teachers during career entry in Central Mexico. HOW, 23(2), 75-88. http://dx.doi.org/10.19183/how.23.2.158.

Mattheoudakis, M. (2007). Tracking changes in pre-service EFL Teacher beliefs in Greece: A longitudinal study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(8), 1272-1288. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.06.001.

McLean, J. (2007). Reflecting on your teaching. In E. Friesen (Ed.), Teaching at the University of Manitoba: A handbook (pp. 5.9-5.12). Winnipeg, CA: University Teaching Services.

Peacock, M. (2001). Pre-service ESL teachers’ beliefs about second language learning: A longitudinal study. System, 29(2), 177-195. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(01)00010-0.

Richards, J. C., & Lockhart, C. (1996). Reflective teaching in second language classrooms. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Seymen, S. (2012). Beliefs and expectations of student teachers about their self and role as teacher during teaching practice course. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 1042-1046. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.245.

Sikka, H., & Timoštšuk, I. (2008). The role of reflection in understanding teaching practice. Problems of Education in the 21st Century, 7, 147-152.

Yuan, R., & Lee, I. (2014). Pre-service teachers’ changing beliefs in the teaching practicum: Three cases in an EFL context. System, 44, 1-12. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2014.02.002.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Nutthida Tachaiyaphum. (2024). Language Education Policies in Multilingual Settings. Multilingual Education Yearbook. , p.147. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-57484-9_9.

2. Thomas S. C. Farrell, Ann H. Farrell. (2024). Handbook of Language Teacher Education. Springer International Handbooks of Education. , p.1. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-43208-8_2-1.

3. 晓莉 张. (2026). A Study on the Current State, Influencing Factors and Developing Strategies of Language Teachers’ Evaluation Competence. Advances in Education, 16(01), p.697. https://doi.org/10.12677/ae.2026.161096.

4. Maria del Rosario Reyes-Cruz. (2020). Emociones y sentido de autoeficacia de los futuros profesores de inglés. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 22, p.1. https://doi.org/10.24320/redie.2020.22.e25.2686.

5. Jardel Coutinho dos Santos, Gloria Luque-Agulló. (2025). Beliefs and Practices of Ecuadorian EFL Preservice Teachers About Teaching Speaking Skills. Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 27(2), p.137. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v27n2.116833.

6. Ximena Paola Buendía-Arias, Andrea André-Arenas, Nayibe del Rosario Rosado-Mendinueta. (2020). Factors Shaping EFL Preservice Teachers’ Identity Configuration. Íkala, 25(3), p.583. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.ikala.v25n03a02.

7. Pedro Antonio Chala Bejarano, Harold Castañeda-Peña, Magda Rodríguez-Uribe, Adriana Salazar-Sierra. (2021). Práctica pedagógica de docentes en formación como práctica social situada. Educación y Educadores, 24(2), p.221. https://doi.org/10.5294/edu.2021.24.2.3.

8. Angie Quintanilla Espinoza, Steffanie Kloss Medina, Pedro Salcedo Lagos. (2018). How do Chilean Pre-Service Teachers Correct Errors in Writing?. Revista Brasileira de Linguística Aplicada, 18(3), p.561. https://doi.org/10.1590/1984-6398201812447.

9. Edgar Lucero, Ángela María Gamboa-González, Lady Viviana Cuervo-Alzate. (2024). The Conception of Student-Teachers and the Pedagogical Practicum in the Colombian ELT Field. Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 26(1), p.169. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v26n1.105139.

10. Anne Edstrom. (2022). Preservice Spanish teachers analyze a nonexemplary lesson: Critical reflection in teacher preparation. Foreign Language Annals, 55(4), p.1109. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12655.

11. Martha García Chamorro, Monica Rolong Gamboa, Nayibe Rosado Mendinueta. (2022). Initial Language Teacher Education: Components Identified in Research. Journal of Language and Education, 8(1), p.231. https://doi.org/10.17323/jle.2022.12466.

12. Ririn Pusparini, Utami Widiati, Arik Susanti. (2021). Pre-service teachers’ beliefs about English Language Teaching and Learning in EFL classroom: A review of literature. JEES (Journal of English Educators Society), 6(1), p.147. https://doi.org/10.21070/jees.v6i1.1212.

13. Juan Carlos Montoya-López, Ayda Vanessa Mosquera-Andrade, Oscar Alberto Peláez-Henao. (2020). Inquiring pre-service teachers’ narratives on language policy and identity during their practicum.. HOW, 27(2), p.51. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.27.2.544.

14. Carla Míguez-Álvarez, Miguel Cuevas-Alonso, María Isabel Doval-Ruiz. (2022). Preservice Teachers’ Perceptions of Linguistic Abilities and Privacy Policies in the Use of Visual Materials During Their Own and Their Tutors’ Lessons. Frontiers in Education, 7 https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.880036.

15. Thomas S. C. Farrell, Ann H. Farrell. (2025). Handbook of Language Teacher Education. Springer International Handbooks of Education. , p.3. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-47310-4_2.

16. Hugo Nelson Areiza-Restrepo. (2026). Views of Language Education in Preservice Teachers Reflected in Their Graduation Projects. Folios, (63), p.229. https://doi.org/10.17227/folios.63-22271.

17. Esther Nanyinza, Ecloss x Ecloss Munsaka. (2023). Contextualization Strategies Used by Pre-service Teachers’ in Teaching English Grammar in Malawian Secondary Schools. EAST AFRICAN JOURNAL OF EDUCATION AND SOCIAL SCIENCES, 4(3), p.172. https://doi.org/10.46606/eajess2023v04i03.0288.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

Copyright (c) 2017 Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.