Rhetorical, Metacognitive, and Cognitive Strategies in Teacher Candidates’ Essay Writing

Las estrategias retóricas, metacognitivas y cognitivas en ensayos escritos por futuros profesores

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n2.60231Keywords:

Argumentative essay, pre-service teachers, think-aloud protocol, writing strategies (en)ensayo argumentativo, estrategias de escritura, estudiantes de un programa de formación de profesores de inglés, protocolo de pensamiento en voz alta (es)

This paper reports on a study about the rhetoric, metacognitive, and cognitive strategies pre-service teachers use before and after a process-based writing intervention when completing an argumentative essay. The data were collected through two think-aloud protocols while 21 Chilean English as a foreign language pre-service teachers completed an essay task. The findings show that strategies such as summarizing, reaffirming, and selecting ideas were only evidenced during the post intervention essay, without the use of communication and socio-affective strategies in either of the two essays. All in all, a process-based writing intervention does not only influence the number of times a strategy is used, but also the number of students who employs strategies when writing an essay—two key considerations for the devising of any writing program.

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n2.60231

Rhetorical, Metacognitive, and Cognitive Strategies in Teacher Candidates’ Essay Writing

Las estrategias retóricas, metacognitivas y cognitivas en ensayos escritos por futuros profesores

Claudio Díaz Larenas*

Universidad de Concepción, Concepción, Chile

Lucía Ramos Leiva**

Universidad Católica del Norte, Antofagasta, Chile

Mabel Ortiz Navarrete***

Universidad Católica de la Santísima Concepción, Concepción, Chile

*claudiodiaz@udec.cl

**luramos@ucn.cl

***mortiz@ucsc.cl

This article was received on September 21, 2016, and accepted on March 20, 2017.

How to cite this article (APA, 6th ed.):

Díaz Larenas, C., Ramos Leiva, L., & Ortiz Navarrete, M. (2017). Rhetorical, metacognitive, and cognitive strategies in teacher candidates’ essay writing. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 19(2), 87-100. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n2.60231.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This paper reports on a study about the rhetoric, metacognitive, and cognitive strategies pre-service teachers use before and after a process-based writing intervention when completing an argumentative essay. The data were collected through two think-aloud protocols while 21 Chilean English as a foreign language pre-service teachers completed an essay task. The findings show that strategies such as summarizing, reaffirming, and selecting ideas were only evidenced during the post intervention essay, without the use of communication and socio-affective strategies in either of the two essays. All in all, a process-based writing intervention does not only influence the number of times a strategy is used, but also the number of students who employs strategies when writing an essay—two key considerations for the devising of any writing program.

Key words: Argumentative essay, pre-service teachers, think-aloud protocol, writing strategies.

Este artículo informa sobre un estudio relacionado con la identificación de estrategias retóricas, metacognitivas y cognitivas utilizadas por profesores en formación antes y después de una intervención centrada en la escritura en proceso de realizar un ensayo argumentativo. Los datos se recolectaron mediante dos protocolos en voz alta, mientras veintiún futuros profesores de inglés chilenos escribían un ensayo. Los resultados muestran que estrategias como resumen, reafirmación y selección de ideas se evidenciaron solo durante el segundo ensayo, sin ejemplos de estrategias de comunicación y socio-afectivas en ninguno de los dos escritos. En suma, una intervención de escritura en proceso no solo influye en la cantidad de estrategias empleadas, sino también en el número de estudiantes que las usan cuando escriben un ensayo argumentativo; dos consideraciones clave para la creación de cualquier programa de escritura.

Palabras clave: ensayo argumentativo, estrategias de escritura, estudiantes de un programa de formación de profesores de inglés, protocolo de pensamiento en voz alta.

Introduction

The research focus of this paper is essay writing because over our years of teaching experience as teacher educators, we have seen, read, and heard that essay writing is one of the skills on which English as a foreign language (EFL) pre-service teachers score the lowest. It is the skill they very often complain about not knowing how to approach. Learning to write means making the appropriate choices to convey meaning, responding to a communicative purpose and considering the audience who will read the written piece. Writing involves a different kind of mental process: thinking, reflecting, preparing, rehearsing, making mistakes, and finding alternative solutions.

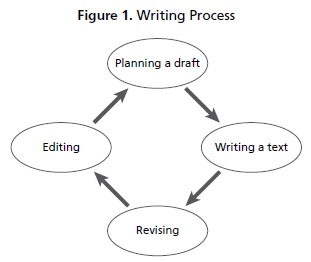

In this research project, the writing skill is approached from a process-oriented perspective, which involves different stages: prewriting, planning, drafting, reflection, feedback from peers or the tutor, proofreading, and editing (Hedge, 2005; Krashen, 1984; Kroll, 2003; White & Arndt, 1991).

The process approach treats all writing as a creative act which requires time and positive feedback to be done well. In process writing, the teacher moves away from being someone who sets students a writing topic and receives the finished product for correction without any intervention in the writing process itself. (Stanley, 2003, p. 1)

Writing is perceived as a recursive process because the writer needs to spend time revisiting and reflecting on his/her work (Tarnopolsky, 2000). Recursive writing allows the rethinking of all stages of one’s writing. Coffin et al.’s (2003) model evidences that the sociocultural aspect is relevant during the writing process. Under a sociocultural perspective, writing is not just a cognitive activity, but becomes a skill in which complex and interacting social, cultural, cognitive, and linguistic processes are involved. A process-based approach constitutes a paradigm shift that views writing as a procedure of developing organization, involving strategies, multiple drafts, and formative feedback.

Studies in process writing have shed light on different ways of teaching writing and developing methods and materials to help learners overcome the difficulties they experience when they write. These findings certainly change the teaching focus from what we write to how we write (Bayat, 2014; Johnson, 2008). Investigating writing problems is therefore challenging and hard work that should be handled carefully. This paper aims at identifying university students’ writing strategies during an essay-like situation before and after being exposed to a pedagogical intervention that consisted of 16 sessions in which students practiced writing essays following a process-based approach. This paper will only focus on unpacking participants’ use of writing strategies through a think-aloud protocol conducted before and after the intervention. The study’s research aims are:

- To identify teacher candidates’ use of writing strategies when completing an argumentative essay.

- To determine the extent to which following a process approach to writing enhances the use of writing strategies by pre-service teachers.

Literature Review

Writing Strategies

Nowadays learning to write is conceived as a task that follows a process that contains different stages as Figure 1 shows.

As Figure 1 shows these stages usually involve planning a written draft and writing a text, besides revising and modifying this text (Hyland, 2004). This process is recursive, which means there is always a shift back for revision and editing. According to Mu (2005), in order to write successfully, learners articulate their prior knowledge concerning linguistic contents (conceptual knowledge) and the application of specific actions to solve writing problems (procedural knowledge). These two types of knowledge are transferred into the use of different writing strategies.

Another important aspect analyzed in this study is the use of writing strategies employed by students. A strategy is any tool, specific action, or behavior someone uses to solve a problem (Coffin et al., 2003; Shapira & Hertz-Lazarowitz, 2005); in other words, when writers write we assume they use strategies to accomplish their task. For Mu (2005) effective writers use rhetorical, metacognitive, cognitive, communicative, and social-affective strategies when they write: (a) Rhetorical strategies deal with types of texts and their structures; (b) metacognitive strategies are related to writers’ self-regulation concerning cognitive procedures when producing a text; (c) cognitive strategies allow users to process, store, and transform different types of knowledge; (d) communicative strategies focus on conveying a message effectively; and (e) social/affective strategies are those which writers employ when interacting with other people. In this present study, students used communicative and social strategies neither before nor after the intervention so the analysis will be limited to the rhetorical, metacognitive, and cognitive strategies.

Rhetorical Strategies

Rhetorical strategies are defined by Mu (2005) as “the strategies the writer organizes to present his ideas in a way that is acceptable” (p. 3). According to the author, rhetorical strategies include: the organization of an essay, the use of the mother tongue to organize paragraphs and sentences, and the presentation of ideas in writing conventions acceptable to native speakers of that language.

Metacognitive Strategies

Metacognitive strategies refer to students’ global skills and knowledge about cognition for helping them raise their self-awareness, direct their own learning, and monitor their own progress. Schmidt (2001) considers them as a conscious process used by learners to control their language learning. According to Wiles (1997), metacognition is defined in terms of “self-management . . . the ability . . . to plan, monitor and revise, or . . . control . . . learning” (p. 17). Such strategies are classified by Ehrman, Leaver, and Oxford (2003) as including

planning on writing, goal setting, preparing for action, focusing, using schemata, activity monitoring, assessing its success, and looking for practice opportunities by writers to help them plan, generate, process, and present information. It also refers to the strategies that enable students to overcome writing difficulties and anxiety. (p. 317)

Some researchers attribute success in writing to metacognition (Mata, 2005; Oxford, 1996, 2011; Parodi, 2003). Authors like Parodi (2003), for example, declare that “metacognitive ability is seen as an essential component in a good writer” (p. 119). This implies that the writer should be aware of his/her learning process in order to be an effective writer.

Cognitive Strategies

Cognitive strategies, on the other hand, enable students to process, transform, and create information in order to assist them in performing complex tasks, using the language effectively and engaging actively “in the knowledge acquisition process” (McCrindle & Christensen, 1995, p. 170). According to Oxford (2011), cognitive strategies refer to organizing information, reading out loud, analyzing, and summarizing, and can also include the use of a dictionary (which can also appear as a social strategy). According to Díaz Rodríguez (2014), “cognitive and metacognitive strategies work together” (p. 19). The difference between both strategies is that the former is used to support development in learning and the latter to monitor and control learning. In fact, cognitive and metacognitive strategies are not independent from one another; they work together while the subject is performing a task (Cook, 2008; Cook & Singleton, 2014).

Method

This is a qualitative and descriptive research study that focuses on eliciting participants’ writing strategies at two specific moments: before and after a process-based writing intervention. The focus of this study relies on identifying what strategies teacher candidates use when they are actually writing the essay through the think-aloud protocol.

The research participants comprised 21 pre-service teachers in their third year of university training in an EFL teacher education program. The average ages are 22 and 23 years old and their English proficiency is at level B2.1 The participants consisted of 16 women and 5 men. In Chile, EFL teacher training programs last about five years and the curriculum targets the development of English language skills, pedagogical knowledge, practicum, and general competencies that allow future teachers to become teachers in all school levels in a public, semi-public, or private school (the three educational realities in Chile). This paper does not approach the impact of the intervention in participants’ essay writing skills as this is beyond the scope of this research project; on the contrary, the interest of this paper is on identifying teacher candidates’ strategy repertoire before and after an intervention consisting of developing writing as a process.

Research Technique

In order to study students’ writing strategies while writing an essay-like text, a think-aloud protocol was used. Ericsson and Simon (1993) proposed the think-aloud protocol as a technique to record the cognitive processes experienced by subjects during the completion of a task. This technique (see Appendix) requires the subjects to express their thoughts aloud during the production of a text without the researcher’s intervention. This technique has been used in the area of cognitive psychology in order to analyze problem-solving tasks and its use has been extended to analyze the processes that occur during text production. According to Ericsson and Simon (1993), this technique may be more effective than others, due to the fact that through verbalization during the completion of a task, important cognitive processes can be revealed. Orality, as Samway (2006) states, is an element that always comes out during text production as writers often talk while writing and arranging words to fit into sentences and sentences to fit into paragraphs and texts.

Procedure

In the context of an academic writing course that is part of the EFL teacher education curriculum, students were exposed to sixteen sessions, taking a process-based approach to essay writing in which they wrote four essays and multiple drafts. The topics covered in the essays were university life, technology, jobs, and sports. Before session one, that is to say, before the intervention, students wrote an essay which was audiotaped through the think-aloud protocol. After session 16, immediately after the end of the intervention, students wrote another essay. The participants’ use of writing strategies was also analyzed through the use of the same think-aloud protocol. The two argumentative essays dealt with different topics, but they kept the traditional organization of such types of writing: introduction, body, and conclusion. Researchers compared pre and post intervention think-aloud protocols in terms of the number of writing strategies that became evidenced.

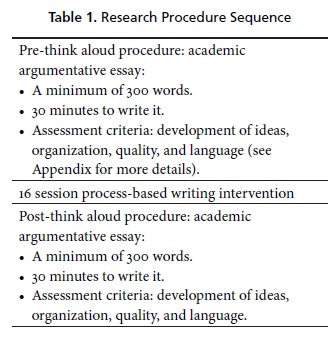

Researchers instructed participants in both the purpose of the study and the think-aloud protocol procedure. The allocated time for writing each essay was 20 minutes. Both think-aloud protocols were conducted at the lab, using microphones and headphones to record students’ thoughts and participants could use either English or Spanish during the verbalization of their thoughts. The same procedure was followed before and after the intervention. Table 1 exemplifies the sequence followed in the research procedure:

From the two think aloud protocols, the participants’ writing strategies were extracted through the content analysis technique.

Data Analysis

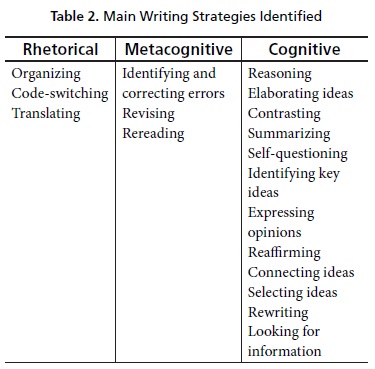

The data collected from the pre and post think-aloud protocols were interpreted using the content analysis technique. Mu’s (2005) categories of English as a second language (ESL) writing strategies (see Appendix) were used as a framework to identify and classify rhetorical, cognitive, and metacognitive strategies. There were no signs of communicative and socio-affective strategies in either of the think-aloud protocols administered to participants.

The data analysis allowed identifying what strategies participants were using and the number of times they were using them when completing their essays. This means, for example, that one single student could have used the same strategy several times during the completion of his/her essay. In this sense, the research interest relies on, firstly, identifying the strategy type and, secondly, examining the number of times one strategy was used during the essay writing. Table 2 shows the main rhetorical, metacognitive, and cognitive writing strategies used by the participants. It can be observed from Table 2 that the participants used different types of writing during the completion of their essays.

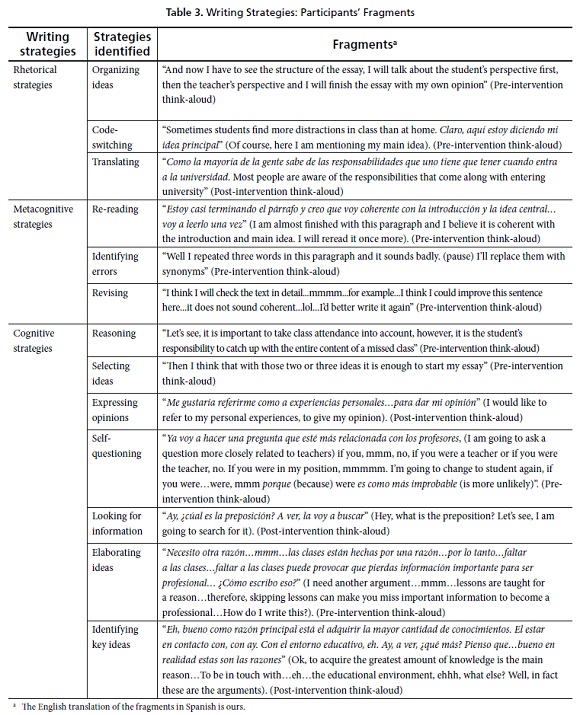

Table 3 shows fragments of participants’ thoughts while writing an argumentative essay. These fragments reveal the use of different types of writing strategies.

Figure 2 shows the number of times each writing strategy was used by participants before and after the intervention, that is, in their writing of the first and second essay after the 16 process-based writing sessions had been completed. As can be seen in Figure 2, the writing strategy reasoning appeared 44 times in the pre think-aloud protocol and 12 times in the post think-aloud protocol. Organizing ideas was used 54 times in the first essay and went down to 20 in the second essay. Elaborating ideas was almost used 60 times before the intervention and participants only used it 21 times after the intervention. Code-switching reached being used 50 times in the first essay to decrease to 17 occasions in the second essay. As for revising, this strategy almost reached 40 occurrences in the first think-aloud and decreased almost 50% in the second think-aloud. It might be that after the 16 sessions of a process-writing approach, participants internalized these strategies to the point that they did not need to verbalize them any longer during the writing of the post-intervention argumentative essay. Interestingly, strategies such as summarizing, reaffirming, selecting ideas and translating did not appear in the first essay and started to be used just after the intervention. It might also be that participants’ background knowledge of the essay topic may trigger their use of certain strategies when completing the task considering that in both think-aloud protocols students had to write an academic argumentative essay.

Figure 2 shows the type of writing strategy students used before and after the intervention. It can be noticed that before the intervention the writing strategies most frequently used by most of the participants were: reasoning, organizing, elaborating ideas, revising, and code-switching. It can also be observed that the use of these strategies decreased in the writing of the essay in the post intervention phase because students widened their repertoire of strategies; in other words, other strategies started to be used after having been exposed to the process-based writing intervention, such as re-reading and rewriting. This is quite logical in the context of the multiple drafts they had to write during the intervention. Strategies such as summarizing, reaffirming, selecting ideas, and translating were declared to be used by students as a result of all the editing they had to do in the process-based writing intervention. Figure 2 also shows that other most frequently used strategies after the intervention were: contrasting, rereading, expressing opinion, connecting ideas, and rewriting. The writing of multiple drafts and the editing work conducted by participants during the process-based writing intervention might clearly have an influence on stimulating the use of different and varied writing strategies as students became more skillful at writing argumentative essays.

A further analysis can be done by looking at Table 4, which details the number of students who used each strategy type before and after the intervention.

Interestingly, during the post-intervention essay more students started to use each one of the strategies. In 14 out of 17 strategies presented in Table 4, there was an increase in the number of students who used them. The strategies of organizing and elaborating ideas, for example, remained equal in terms of the number of students who employed them before and after the intervention. Only in the strategy of reasoning was there a decrease in the number of students using it after the intervention. Both cognitive and metacognitive types of strategies had a meaningful increase in number during the post intervention essay.

All in all, while some writing strategies appeared less frequently (explained above) during the post intervention essay, there was a clear increase in the number of students who started to employ each strategy in their essays after the intervention.

Discussion

From the findings it could be observed that the writing strategies most frequently used before the intervention were not the most frequently used after the intervention. In other words, while the use of some writing strategies decreased in frequency after the intervention, others increased. Sadi and Othman (2012) argue that good writers devote more time to planning, organizing, and revising their ideas. On the other hand, less skillful writers spend less time on planning and revising. Their revision is at a surface level. In this research study, pre-intervention writing strategies tended to focus on planning the argumentative essay; however, after participants had gone through the process writing oriented intervention, they focused on the writing of the argumentative essay itself; in other words, they connected ideas, reread and rewrote them while completing the essay. After the intervention on process writing, learners invested more time in the process of finishing their essay by making use of a more varied repertoire of strategies such as connecting and contrasting their ideas to produce a sound piece of writing.

Some participants used strategies that were not observed before the intervention such as: summarizing, translating, and reaffirming. This might show that students’ cognitive activity during the process of writing the essay became much more productive and oriented towards finishing a high quality piece of work. The use of these new strategies implies that students are probably more aware of the need of using those strategies when writing an essay or an academic text. Besides, it can be inferred that the practice of writing four consecutive essays, taking a process-based approach, favored the use of other strategies which had not been used before the intervention. Thus this 16-session intervention triggered the use of a more varied repertoire of writing strategies, as shown in the data analysis section above with the strategies of selecting ideas, summarizing, and reaffirming which only started to be used by participants in the post-intervention argumentative essay. This might have been due to the fact that participants had to work on multiple drafts and did a great deal of editing. It might be that drafting and editing are two stages in the writing process which require a number of strategies that activate the participants’ use of other strategies as a chain-like effect.

One of these writing strategies, not used before the intervention, was selecting ideas. Selecting ideas is a complex strategy because students need to learn how to ignore information that is irrelevant, no matter what language they use. Indeed, selecting ideas can be challenging in both the mother tongue and in the second language. When students become proficient in the use of the selecting ideas strategy, they are able to integrate ideas that are meaningful for the text. Therefore, teachers should devote time to teach this type of strategies explicitly in order to help students become effective strategy users and effective writers in the end whoever their audience may be.

The strategy of translation from the mother tongue to the foreign language appeared to be used after the intervention. The use of this strategy has been a topic of discussion in EFL training programs, since most teaching methods have not granted the mother tongue an important role. Translating is supposed to be a characteristic of less skilled writers, who usually focus on single words (Sadi & Othman, 2012). Therefore, many of the techniques and strategies used in the classroom do not involve the use of the mother tongue (Martín, 2001). In this regard, it can be inferred that students, and especially those with advanced English proficiency, did not use this strategy, or at least not very often. This result is opposed to the studies that suggest that “mother tongue is the main resource when students write in L2” (Alhaisoni, 2012, p. 152). For these research participants, the intervention did trigger their use of translating when they were completing their essays so this strategy became a tool learners turned to when being involved in L2 writing.

On the other hand, the use or non-use of a strategy may have different explanations. First, when there is limited time to produce a piece of text, some strategies may appear more easily to be applied than others. This might explain, for example, the fact that only rhetorical, cognitive, and metacognitive strategies were found during the administration of the two think-aloud protocols. There were no signs of communication and socio-affective strategies because the time the participants had to complete the task (pre and post intervention) was brief and this timing issue (30 minutes only) might have had an effect on the fact that participants did not use these two types of strategies. The participants’ use of some writing strategies might demand a higher cognitive load when being used on the part of students, which might finally result in students’ being reluctant to use some of them. For example, connecting ideas when writing an essay clearly demands a higher cognitive load than self-questioning about what is being written (Novak, 1998). One important factor to take into consideration is that participants had to express their thoughts aloud, so they were exposed to a situation they were not used to. Furthermore, the fact of having to verbalize what you are thinking about is a determining factor because not everyone can block out distractions to perform the task. Students may make an effective use of writing strategies, but may not have the same ability to express their use of such strategies. The situation itself is not natural, not spontaneous, but imposed rather, which adds another variable.

As Warschauer (2010) declares, it is crucial to keep in mind those strategies students really need to write effectively whichever audience they may be addressing. In this sense, the participants’ use of strategies is a personal and subjective endeavour, which does not allow stating that students must be exposed to fixed didactic sequences of writing strategies. It is then the teacher’s role to design language activities that can contribute to enhance students’ metacognitive, cognitive, and socio-affective processes during writing and can promote the use of a wide variety of strategies to resort to when there are communication breakdowns. When learners develop a repertoire of writing strategies, they can try out different ones when they experience a communication breakdown so as to become strategic writers of English.

Conclusion

This study is a contribution to research on writing strategies in an EFL context at the university level. In this respect, it can be concluded that the think-aloud protocol allowed the observation of different processes that occur in the writer’s mind when writing a text in an exam situation. Therefore, it can be stated that if these processes are more frequently observed, it can be possible to identify how our students face a writing task, especially when they feel under pressure. Based on that knowledge, teachers should be able to support students’ writing process by using different techniques and teaching the appropriate strategies during the development of an academic text. Besides, this study also enabled us to observe what types of writing strategies students use before and after an intervention.

As a final thought, the findings from this research should be considered by EFL teaching programs in Chile and elsewhere. Teaching EFL requires a lot of practice, even more in pre-service teachers. Thus, it is essential that future teachers of English can develop an understanding of how the teaching and learning of writing are developed and which are the cognitive, metacognitive, and socio-affective processes involved in it in order for teachers to come to see writing as a process involving different stages which lead to the use of varied writing strategies to become effective.

1B2 level, according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEF or CEFR) and the Council of Europe. Level B2-Upper intermediate is defined as follows: A person who can understand the main ideas of complex texts and can produce clear detailed text. S/he can spontaneously enter into a conversation (https://www.eur.nl/english/ltc/cefr_levels/).

References

Alhaisoni, E. (2012). A think-aloud protocols investigation of Saudi English major students’ writing revision strategies in L1 (Arabic) and L2 (English). English Language Teaching, 5(9), 144-154. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v5n9p144.

Bayat, N. (2014). The effect of the process writing approach on writing success and anxiety. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 14(3), 1133-1141.

Coffin, C., Curry, M. J., Goodman, S., Hewings, A., Lillis, T. M., & Swann, J. (2003). Teaching academic writing: A toolkit for higher education. London, UK: Routledge: Taylor & Francis Group.

Cook, V. (2008). Second language learning and language teaching. Newcastle, UK: Hodger Education.

Cook, V., & Singleton, D. (2014). Key topics in second language acquisition. Ontario, CA: MM textbooks.

Díaz Rodríguez, A. (2014). Retórica de la escritura académica: Pensamiento crítico y discursivo [Academic writing rhetoric: critical and discursive thought]. Medellín, CO: Universidad de Antioquia.

Ehrman, M. E., Leaver, B. L., & Oxford, R. L. (2003). A brief overview of individual differences in second language learning. System, 31(3), 313-330. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(03)00045-9.

Ericsson, K. A., & Simon, H. A. (1993). Protocol analysis verbal reports as data (Rev. ed.). Cambridge, US: mit Press.

Hedge, T. (2005). Writing. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Hyland, K. (2004). Genre and second language writing. Ann Arbor, US: University of Michigan Press. http://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.23927.

Johnson, A. P. (2008). Teaching reading and writing: A guidebook for tutoring and remediating students. New York, US: Rowman and Littlefield Education.

Krashen, S. D. (1984). Writing: Research, theory and applications. Oxford, UK: Pergamon Institute of English.

Kroll, B. (2003). Exploring the dynamics of second language writing. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139524810.

Mackey, A., & Gass, S. M. (2005). Second language research: Methodology and design. New Jersey, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Martín, J. (2001). Nuevas tendencias en el uso de la L1 [New trends in L1 usage]. Estudios de Lingüística Inglesa Aplicada, 2, 159-169.

Mata, F. S. (2005). Procesos cognitivos en la expresión escrita: modelos teóricos e investigación empírica [Cognitive processes in written expression: Theoretical models and empirical research]. En F. S. Mata (Ed.), La expresión escrita de alumnos con necesidades especiales: procesos cognitivos (pp. 15-43). Málaga, es: Ediciones Aljibe.

McCrindle, A. R., & Christensen, C. A. (1995). The impact of learning journals on metacognitive and cognitive processes and learning performances. Learning and Instruction, 5(2), 167-185. http://doi.org/10.1016/0959-4752(95)00010-Z.

Mu, C. (2005). A taxonomy of ESL writing strategies. In Proceedings Redesigning Pedagogy: Research, Policy, Practice (pp. 1-10). Singapore, sg: qutePrints.

Novak, J. D. (1998). Conocimiento y aprendizaje: los mapas conceptuales como herramientas facilitadoras para escuelas y empresas [Knowledge and learning: Conceptual maps as facilitating tools for schools and companies]. Madrid, es: Alianza.

Nunan, D., & Bailey, K. M. (2009). Exploring second language classroom research: A comprehensive guide. Boston, US: Heinle Cengage Learning.

Oxford, R. L. (1996). Language learning strategies around the world: Cross-cultural perspectives. Manoa, US: University of Hawai’i Press.

Oxford, R. L. (2011). Teaching and researching language learning strategies. New Jersey, US: Longman.

Parodi, G. (2003). Relaciones entre lectura y escritura: una perspectiva cognitiva-discursiva [Relations between reading and writing: A cognitive-discursive perspective]. Valparaíso, CL: EUVSA.

Sadi, F. F., & Othman, J. (2012). An investigation into writing strategies of Iranian EFL undergraduate learners. World Applied Sciences Journal, 18(8), 1148-1157.

Samway, K. (2006). When English language learners write. Portsmouth, US: Heinemann.

Schmidt, R. (2001). Attention. In P. Robinson (Ed.), Cognition and second language instruction (pp. 3-32). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139524780.003.

Shapira, A., & Hertz-Lazarowitz, R. (2005). Opening windows on Arab and Jewish children’s strategies as writers. Language, Culture, and Curriculum, 18(1), 72-90. http://doi.org/10.1080/07908310508668734.

Stanley, G. (2003). Approaches to process writing. Retrieved from https://learning-development.britishcouncil.org/file.php/1880/SD_adult_english_process_writing.pdf.

Tarnopolsky, O. (2000). Writing English as a second or foreign language: A report from Ukraine. Journal of Second Language Writing, 9(3), 209-226. http://doi.org/10.1016/S1060-3743(00)00026-6.

Warschauer, M. (2010). Invited commentary: New tools for teaching writing. Language Learning & Technology, 14(1), 3-8.

White, R., & Arndt, V. (1991). Process writing. Essex, UK: Addison Wesley Longman.

Wiles, W. (1997). Metacognitive strategy programming for adult upgrading students (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada.

About the Authors

Claudio Díaz Larenas holds a PhD in Education and a Master of Arts in Linguistics. He is an EFL teacher at Universidad de Concepción, Chile. His research interests are teacher cognition and beliefs.

Lucía Ramos Leiva holds a Master of Arts in Higher Education and is an EFL teacher at Universidad Católica del Norte. Her research interest is teacher education.

Mabel Ortiz Navarrete holds a PhD in Linguistics, a Master of Arts in Information and Communications Technology and is an EFL teacher at Universidad Católica de la Santísima Concepción. Her research interests are feedback, cooperative learning and ICT tools.

Acknowledgements

This paper is funded by the research projects: FONDECYT No. 11150273 “Use of focused corrective feedback in a wiki-based collaborative writing environment”, and FONDECYT No. 1150889 “Las dimensiones cognitivas, afectivas y sociales del proceso de planificación de aula y su relación con los desempeños pedagógicos en estudiantes de práctica profesional y profesores nóveles de pedagogía en inglés”.

Appendix: Think-Aloud Protocol (Mackey & Gass, 2005; Nunan & Bailey, 2009)

Protocol to collect information about students’ cognitive process while developing a writing task through the use of the Think Aloud Protocol

Instructions

- Directions: For this task, you will write an essay in response to a question that asks you to state, explain, and support your opinion on an issue.

- The essay might contain a minimum of 300 words. Your essay will be judged on the quality of your writing. This includes the development of your ideas, the organization of your essay, and the quality and accuracy of the language you use to express your ideas.

- You have 30 minutes to plan and complete the essay.

- Write your essay in the space provided.

- Essay topic: Some people believe that university students should be required to attend classes. Others believe that going to classes should be optional for students. Which point of view do you agree with? Use specific reasons and examples to support your answer.

1. Setting

The researcher has to prepare the setting for students to feel relaxed and comfortable.

2. Instruction

The researcher has to give students the instructions clearly.

- Here is a task similar to the ones you have done in class. Remember the steps you need to follow to write an argumentative essay and see if you can successfully complete this task. As you write the essay on Google Docs, try to speak your thoughts aloud into the microphone while you perform the task and not after the task. Speak in a clear voice.

- The essay is on the following topic: Some people believe that university students should be required to attend classes. Others believe that going to classes should be optional for students. Which point of view do you agree with? Use specific reasons and examples to support your answer.

- You have 30 minutes to write this essay. When you are ready, tell the researcher to start the recording.

3. Researcher intervention and prompting during the activity

The researcher is not supposed to interfere in the process. Maybe only when s/he realizes that the student(s) has(have) stopped speaking out loud can the researcher prompt the subject by telling him/her: “Go on”, “Keep on talking”.

Avoid using phrases like “Are you sure?” and “That’s good”. Instead, use only phrases like “What makes you say that?” “What made you do that?” “What are you thinking about at this moment?”, and “Please keep talking”.

4. Recording

The session will be videotaped by the researcher. It would be advisable to try any device you are using beforehand to make sure the recording will be fine.

5. Transcription of the protocol

Once the recording session is finished, the researcher has to transcribe what the student/subject recorded. The transcription must be as accurate as possible to get the information needed for the research being carried out.

References

Alhaisoni, E. (2012). A think-aloud protocols investigation of Saudi English major students’ writing revision strategies in L1 (Arabic) and L2 (English). English Language Teaching, 5(9), 144-154. http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/elt.v5n9p144.

Bayat, N. (2014). The effect of the process writing approach on writing success and anxiety. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 14(3), 1133-1141.

Coffin, C., Curry, M. J., Goodman, S., Hewings, A., Lillis, T. M., & Swann, J. (2003). Teaching academic writing: A toolkit for higher education. London, UK: Routledge: Taylor & Francis Group.

Cook, V. (2008). Second language learning and language teaching. Newcastle, UK: Hodger Education.

Cook, V., & Singleton, D. (2014). Key topics in second language acquisition. Ontario, CA: MM textbooks.

Díaz Rodríguez, A. (2014). Retórica de la escritura académica: Pensamiento crítico y discursivo [Academic writing rhetoric: critical and discursive thought]. Medellín, CO: Universidad de Antioquia.

Ehrman, M. E., Leaver, B. L., & Oxford, R. L. (2003). A brief overview of individual differences in second language learning. System, 31(3), 313-330. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(03)00045-9.

Ericsson, K. A., & Simon, H. A. (1993). Protocol analysis verbal reports as data (Rev. ed.). Cambridge, US: mit Press.

Hedge, T. (2005). Writing. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Hyland, K. (2004). Genre and second language writing. Ann Arbor, US: University of Michigan Press. http://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.23927.

Johnson, A. P. (2008). Teaching reading and writing: A guidebook for tutoring and remediating students. New York, US: Rowman and Littlefield Education.

Krashen, S. D. (1984). Writing: Research, theory and applications. Oxford, UK: Pergamon Institute of English.

Kroll, B. (2003). Exploring the dynamics of second language writing. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139524810.

Mackey, A., & Gass, S. M. (2005). Second language research: Methodology and design. New Jersey, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Martín, J. (2001). Nuevas tendencias en el uso de la L1 [New trends in L1 usage]. Estudios de Lingüística Inglesa Aplicada, 2, 159-169.

Mata, F. S. (2005). Procesos cognitivos en la expresión escrita: modelos teóricos e investigación empírica [Cognitive processes in written expression: Theoretical models and empirical research]. En F. S. Mata (Ed.), La expresión escrita de alumnos con necesidades especiales: procesos cognitivos (pp. 15-43). Málaga, es: Ediciones Aljibe.

McCrindle, A. R., & Christensen, C. A. (1995). The impact of learning journals on metacognitive and cognitive processes and learning performances. Learning and Instruction, 5(2), 167-185. http://doi.org/10.1016/0959-4752(95)00010-Z.

Mu, C. (2005). A taxonomy of ESL writing strategies. In Proceedings Redesigning Pedagogy: Research, Policy, Practice (pp. 1-10). Singapore, sg: qutePrints.

Novak, J. D. (1998). Conocimiento y aprendizaje: los mapas conceptuales como herramientas facilitadoras para escuelas y empresas [Knowledge and learning: Conceptual maps as facilitating tools for schools and companies]. Madrid, es: Alianza.

Nunan, D., & Bailey, K. M. (2009). Exploring second language classroom research: A comprehensive guide. Boston, US: Heinle Cengage Learning.

Oxford, R. L. (1996). Language learning strategies around the world: Cross-cultural perspectives. Manoa, US: University of Hawai’i Press.

Oxford, R. L. (2011). Teaching and researching language learning strategies. New Jersey, US: Longman.

Parodi, G. (2003). Relaciones entre lectura y escritura: una perspectiva cognitiva-discursiva [Relations between reading and writing: A cognitive-discursive perspective]. Valparaíso, CL: EUVSA.

Sadi, F. F., & Othman, J. (2012). An investigation into writing strategies of Iranian EFL undergraduate learners. World Applied Sciences Journal, 18(8), 1148-1157.

Samway, K. (2006). When English language learners write. Portsmouth, US: Heinemann.

Schmidt, R. (2001). Attention. In P. Robinson (Ed.), Cognition and second language instruction (pp. 3-32). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139524780.003.

Shapira, A., & Hertz-Lazarowitz, R. (2005). Opening windows on Arab and Jewish children’s strategies as writers. Language, Culture, and Curriculum, 18(1), 72-90. http://doi.org/10.1080/07908310508668734.

Stanley, G. (2003). Approaches to process writing. Retrieved from https://learning-development.britishcouncil.org/file.php/1880/SD_adult_english_process_writing.pdf.

Tarnopolsky, O. (2000). Writing English as a second or foreign language: A report from Ukraine. Journal of Second Language Writing, 9(3), 209-226. http://doi.org/10.1016/S1060-3743(00)00026-6.

Warschauer, M. (2010). Invited commentary: New tools for teaching writing. Language Learning & Technology, 14(1), 3-8.

White, R., & Arndt, V. (1991). Process writing. Essex, UK: Addison Wesley Longman.

Wiles, W. (1997). Metacognitive strategy programming for adult upgrading students (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Haytham Bakri. (2023). Rhetorical Strategies for Teaching Essay Writing: A Case Study Involving Saudi ESL Students. SSRN Electronic Journal, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4497526.

2. Maryam Esmaeil Nejad, Siros Izadpanah, Ehsan Namaziandost, Behzad Rahbar. (2022). The Mediating Role of Critical Thinking Abilities in the Relationship Between English as a Foreign Language Learners’ Writing Performance and Their Language Learning Strategies. Frontiers in Psychology, 13 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.746445.

3. Halit Karatay, Kadir Vefa Tezel, Emre Yazıcı, Talha Göktentürk. (2023). The effect of the 4 + 1 planned writing and evaluation model on creative writing: An action research study. South African Journal of Education, 43(Supplement 2), p.S1. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v43ns2a2161.

4. Zulaikha Khairuddin, Noor Hanim Rahmat, Maizura Mohd Noor, Zurina Khairuddin. (2021). The Use of Rhetorical Strategies in Argumentative Essays. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 29(S3) https://doi.org/10.47836/pjssh.29.s3.14.

5. Pradeep Kumar Misra. (2021). Learning and Teaching for Teachers. , p.59. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-3077-4_4.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

Copyright (c) 2017 PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.