Motivating and Demotivating Factors for Students With Low Emotional Intelligence to Participate in Speaking Activities

Factores motivantes y desmotivantes identificados en estudiantes con inteligencia emocional baja a participar en actividades orales

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n2.60652Keywords:

Emotional intelligence, foreign language learning, motivation, speaking skills (en)aprendizaje de lenguas extranjeras, habilidad oral, inteligencia emocional, motivación (es)

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n2.60652

Motivating and Demotivating Factors for Students With Low Emotional Intelligence to Participate in Speaking Activities

Factores motivantes y desmotivantes identificados en estudiantes con inteligencia emocional baja a participar en actividades orales

Mariza G. Méndez López*

Moisés Bautista Tun**

Universidad de Quintana Roo, Chetumal, Mexico

*marizam@uqroo.edu.mx

**0809303@uqroo.edu.mx

This article was received on October 22, 2016, and accepted on April 28, 2017.

How to cite this article (APA, 6th ed.):

Méndez López, M. G., & Bautista Tun, M. (2017). Motivating and demotivating factors for students with low emotional intelligence to participate in speaking activities. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 19(2), 151-163. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n2.60652.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

The study aims to understand what factors may motivate and demotivate students with low emotional intelligence to participate in speaking activities during English class. Participants wrote an emotions journal to identify factors affecting student participation and were then interviewed at the end of the study period in order to elaborate on their experiences. Results showed that male participants experienced a wide range of negative emotions while females experienced a reduced number. However, in comparison, women experienced negative emotions frequently while men experienced them occasionally. Results also showed that males and females differed in the way that they perceived and faced situations, and in how they regulated the emotions generated by these situations.

Key words: Emotional intelligence, foreign language learning, motivation, speaking skills.

Este estudio tiene como objetivo entender los factores que pueden motivar y desmotivar a estudiantes con inteligencia emocional baja a participar en actividades orales en sus clases de inglés. Los participantes escribieron un diario para identificar los factores que afectaron su participación y fueron entrevistados al final del estudio con el propósito de profundizar en sus experiencias de aprendizaje. Los resultados mostraron que los hombres sienten una amplia gama de emociones negativas mientras que las mujeres experimentaron un número reducido de estas, aunque con mayor frecuencia que los hombres. Los hombres y las mujeres se diferencian en la forma en que perciben y enfrentan situaciones, y en cómo regulan las emociones originadas por estas.

Palabras clave: aprendizaje de lenguas extranjeras, habilidad oral, inteligencia emocional, motivación.

Introduction

Learning a foreign language requires investment in the practice of linguistic skills. The skill of speaking in the target language has been revealed as being the most challenging for language learners due to its interactive nature (Harumi, 2011; Méndez, 2011; Woodrow, 2006; Zhang & Head, 2010). Students learning English as a foreign language (EFL) in a non-English speaking country have limited opportunities to practice their speaking skills compared to those doing so in an English-speaking country (Zhang, 2009). Although language learners recognise the importance of oral practice to achieve communicative competence, linguistic problems (Harumi, 2011) and the reactions they trigger (Méndez & Fabela, 2014) often cause students to avoid oral participation or remain passive when they are asked to express their ideas or opinions in language class. Some studies have reported that most language learners are concerned about making pronunciation or grammar mistakes when participating in classes because they fear teachers’ negative judgement or their peers’ mockery (Kitano, 2001; Méndez & Peña, 2013; Yan & Horwitz, 2008). Xie (2010) and Zhang and Head (2010) carried out two studies in China and found that “the reticence to speak or participate in classroom activities, usually attributed to the cultural and educational environment in which learners have developed, is positively affected by the controlling teaching practices imposed on students and not by culture” (Méndez, 2011, p. 54).

This is supported by motivation theories that suggest that teachers who exercise authority and control in the classroom affect students’ motivation negatively whereas if teachers are flexible and comprehensive can positively improve it (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Littlewood, 2000). Thus, the negative attitudes and behaviours manifested by students may cause frustration and feelings of failure in teachers when their students seem unwilling to cooperate and participate in English speaking activities. Tsiplakides and Keramida (2009) suggest that teachers fail to recognise that these attitudes are a result of student anxiety, instead attributing them to a lack of motivation or poor attitude. Thus, it is important for teachers to recognise learners’ real emotions and how they affect their motivation to speak in foreign language class.

In order to contribute to the literature on speaking ability in foreign language learning, this study aimed to understand what factors may motivate or demotivate students with low emotional intelligence (EI) to participate in speaking activities during English class.

Emotional Intelligence and Speaking in a Foreign Language

Emotional intelligence is the capacity to control and regulate one’s own feelings and those of others, and use them as a guide for thought and action (Barchard & Hakstian, 2004). People who have developed EI skills can comprehend and express their own emotions, identify emotions in others, regulate affect, and utilize moods and emotions to impel adaptive behaviours (Mayer & Salovey, 1997).

According to Salovey, Mayer, Caruso, and Lopes (2003), EI is composed of four related abilities. They state that if people possess a high level of EI, they are able to accurately perceive how both they and others feel, use those feelings to help with the task at hand, comprehend both the way those feelings have arisen and how they will change, and then manage those feelings effectively to achieve a positive result. People who have developed a high EI are creative performers compared to those with a lower EI (Wolfradt, Felfe, & Köster, 2002). The development of EI is said to reduce stress not only for individuals but also for organisations, because it “enables employees to achieve work/life balance” and “enhance leadership capability and potential” (Chapman, 2014, p. 93). In the same vein, Zaremba (as cited in Boonkit, 2010, p. 1306) points out that speaking skills are “usually placed ahead of work experience, motivation, and academic credentials as recruitment criteria by employers”. Boonkit (2010) considers speaking as “one of the macro skills that should be developed as a means of effective communication” (p. 1036), not only in first but also in second language learning contexts.

In the field of second language learning, different studies have been undertaken on the influence of EI on speaking ability. Soodmand Afshar and Rahimi (2014) found that EI significantly correlated with the predicted speaking ability of Iranian EFL learners. According to their results, students who are more assertive and who tend to have higher social responsibility and self-appraisal abilities are good speakers. In the same vein, Lopes et al. (2004) found that people with effective emotional abilities are able to use these to their advantage and enrich their interactions with friends. The results of the study conducted by Bora (2012) support this, revealing that students with a high level of EI who participated in the study were more willing to participate in speaking activities due to their high levels of self-esteem and social skills.

The speaking performance of foreign language students can be affected by diverse factors generated by performance conditions, such as pressure, planning, and the amount of support provided. Furthermore, affective factors such as motivation, confidence, and anxiety can affect learners’ willingness to participate in class (Méndez & Fabela, 2014; Shumin, 2002). As stated by Mohammadi and Mousalou (2012), foreign language students try to avoid situations in which they have to speak. Although some studies refer to this reticence as resulting from controlling teaching practices (Xie, 2010; Zhang & Head, 2010), it is necessary to examine the role of low EI on speaking in a second or foreign language. However, most studies undertaken on EI and speaking have focused on the positive relationship between these two variables. Thus, it is necessary to ascertain how students with a low EI deal with speaking in a foreign language and what factors motivate or demotivate them during this activity in foreign language class. This article reports on a qualitative study carried out to identify the factors that motivate or demotivate the oral participation of students with a low EI enrolled in an English language teaching (ELT) programme at a state university in southern Mexico.

Method

This study followed a qualitative approach given that its objective was to gain a deeper understanding of the factors that encourage or discourage oral participation during foreign language classroom instruction. The purpose of the study was to explore students’ perceptions regarding classroom participation and discover the factors affecting their oral participation, using the following research question: What factors influence the participation of male and female students with a low EI in classroom oral activities?

Participants

The participants of this study were ten men and ten women enrolled in the ELT program at a public university in the South East of Mexico during the 2013 spring semester. The participants selected scored the lowest EI on the Trait Meta-Mood Scale 24 (TMMS-24) questionnaire. Participants consisted of four beginners, four intermediate, and two advanced level students from ages 18 to 25.

Instruments

Three instruments were used for the purpose of this study. First, the TMMS-24 (Salovey, Mayer, Goldman, Turvey, & Palfai, 1995) was used to measure the students’ EI. The TMMS-24 measures three key dimensions of EI: emotional perception, emotional comprehension, and emotional regulation. The version of this instrument that was adapted to Spanish by Fernández-Berrocal et al. (1998) was used in order to ensure that participants understood it.

After the participants had been selected, they were asked to write an entry in an emotions journal once a week for a period of seven weeks. The participants used this instrument to report their experiences of their participation in oral production activities in language class. The emotions journal entries enabled the identification of factors influencing students’ oral participation.

Semi-structured interviews were carried out at the end of the study. The interview guide was designed to allow participants to express their motivations for speaking or refraining from speaking during classroom activities (see Appendix). Interviews were recorded and transcribed, and the transcripts then checked against the original audio recording for accuracy. The purpose of this third instrument was to deepen understanding of the participants’ experiences and confirm what these students with a low EI had reported in their journal entries. The interviews were carried out in Spanish to prevent any kind of misunderstanding.

Data Analysis

Data were analysed using Thematic Analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006), which offers an accessible and theoretically flexible approach to analysing qualitative data. Once the data had been coded and collated, the codes were classified into potential themes and the data extracts collated within the themes identified. The relationship between codes, themes, and the different levels within the themes was analysed by both researchers in order to validate the final themes selected. Although a set of possible themes was developed, it was necessary to refine them, leading to the realization that there may not have been enough data to support some themes, which were then discarded. Data were classified into the themes, taking into account the fact that the classification was meaningfully coherent and that there was a clear distinction between themes. The collected extracts for each theme were read again to consider whether they could form a coherent pattern. When the themes did not form a coherent pattern, they were reworked to find a suitable theme for the extracts that did not fit within any of the themes already developed. The final themes were assigned concise names.

Results

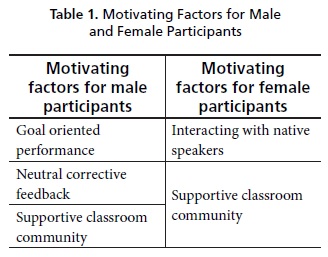

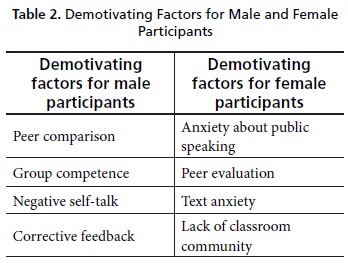

The research question aimed to reveal factors that influence students’ oral participation during English language class and to identify factors affecting male and female students (see Table 1). Even though male participants described having felt a greater variety of negative feelings, by the end of the study, these had been transformed into more positive ones. Although female participants showed fewer negative feelings, they felt them more frequently (see Table 2).

Motivating Factors for Male Participants

Goal Oriented Performance

During the activities, the participants, when speaking, compared their fluency with that of their classmates, realizing that their progress was slower. Considering themselves incompetent in terms of their linguistic skills gave them a feeling of desperation and motivated them to practice harder for oral exams and learn more vocabulary in order to perform better in oral activities. As one of the participants reported:1

This week I was fine...happy because of the grade I got in my basic English course, but that day I was also given the result I got in my English language course and I didn’t get the grade I expected, that made me feel powerless, even more because I knew that on my speaking exam I didn’t perform as good as on the writing exam. I started and finished this week with the desire of participating with more frequency, I started feeling more confident to speak English in class, to ask questions or to talk with classmates. Although sometimes I didn’t produce the sentences correctly, I made an effort and took notes about the corrections in order to avoid making the same mistakes again. Days later, while I was doing my English homework, I felt nostalgia again when I realized I have a great lack of vocabulary, but at the same time I felt motivated to learn because my goal of being the best won’t be reached by itself. (Journal, Week 3, Christian2)

It is clear that students have performance goals in order for their linguistic competence to be judged positively (Dweck, 1986). Performance goals force students to direct all their efforts into outperforming their classmates in order to maintain their language ability and avoid negative judgments (Ames, 1992; Elliot & Dweck, 1988; Nicholls, 1984).

Neutral Corrective Feedback

The participants felt motivated to speak during the English class once they had realized that the teachers were providing feedback in a neutral way. Some participants revealed that they participated more in classes where the teachers corrected the errors by writing them on the whiteboard or by showing slide projections of errors and explaining them to the whole class without pointing out the student who had made the mistake. During the study period, participants from the intermediate semesters felt good when they realized that teachers provided corrective feedback to all students who had made mistakes. They stated that they felt that teachers had no preference for some students over others in the classroom, making it a place where they felt a sense of equity. As one participant states:

Many (of the students) made pronunciation mistakes and the teacher gave them feedback but not me, she usually corrects me whenever I make a mistake in all the activities, this makes me feel that the teacher is aware of the mistakes of everyone and not only mine. Thinking in that way, makes possible that I do not feel afraid to speak. (Journal, Week 4, Andrew)

Supportive Classroom Community

Participants reported being encouraged to participate actively in class. Intermediate participants felt confident when interacting with classmates, as, in the absence of any competence, there was a strong sense of cooperation and support in the group. No one was mocked when they made a mistake during oral presentations. Participants also reported no impolite attitudes in their classmates, which could have affected the performance of the speaker. Participants did not demonstrate annoyance when receiving feedback from classmates. This is supported by Mall-Amiri and Hesami (2013) who stated that “peer feedback equips students with socially affective strategies such as listening carefully, speaking at the right moment, expressing clearly, and appreciating others” (p. 15). As one participant explains:

I am not afraid of speaking English all the time...sometimes I feel like participating...because in general...the actions and attitudes of my classmates, towards me are positive...they also want to speak and express their ideas. I feel that we all win. (Interview, Karl)

Motivating Factors for Female Participants

Interacting With Native Speakers

Rozina (2001) states that native speakers can speak at a relatively fast speed thanks to the language stored in their mental lexicon. Participants felt disadvantaged due to their limited vocabulary compared with that of native speakers. Thus, they took every opportunity to speak with native English speakers, which gave them a feeling of great confidence. They not only wanted to keep practicing with native speakers in order to learn from them, but also wanted to use different strategies to improve their speaking ability (e.g., learning vocabulary or practicing with friends or classmates with whom they felt comfortable). Thus, they felt less of the anxiety or fear that had prevented them from speaking during oral activities. As one participant states:

I feel happy because I realize I am able to keep a conversation with a native (English speaker) and that she is able to understand what I say. As a result, I am not afraid anymore to participate in the classroom. (Journal, Week 6, Camrin)

Supportive Classroom Community

The participants felt comfortable with the classroom environment that had been developed, a factor that was essential for their improvement. They described having felt satisfied with both their performance during speaking activities and the grades they obtained, realizing that they were improving constantly and that, also, they were more resilient to making errors in front of their peers. Shaffer and Anundsen (1993) emphasise that being able to interact in a supportive classroom community helps students achieve their goals. It seems that the environment developed in the classroom featured in this study helped students to feel confident, thus helping them to develop their linguistic abilities. As one participant states:

Due to the fact that in the classroom we are in a comfortable and reliable environment, I don’t feel nervous or anxious. (Interview, Week 5, Anahí)

Demotivating Factors for Male Participants

Peer Comparison

Male participants described feeling nervous before oral participation and worried that their classmates who had a higher level of English were going to mock them. As a result, it took some time for students to participate in oral activities and answer questions. When they finally dared to speak, they spoke quickly and incoherently.

Prejudice in schools is especially troubling because schools are public places in which students learn to negotiate and construct knowledge of differences. When prejudicial beliefs go unexamined in schools, students are not given the opportunity to deconstruct prejudicial knowledge. The impact of prejudicial attitudes on students is wide ranging, spanning from lower school performance to poor physical and mental health. (Camicia, 2007, p. 219)

As one participant commented:

Many of them know [referring to her classmates] dominate more the language, and because of that reason, sometimes I feel that the lack of knowledge...make me...as if they were going to talk bad things about me, or I don’t know. (Interview, Fer)

Group Competence

As usually happens inside classrooms, a division into small groups of friends tends to emerge, which generates an implicit sense of competition. This action created a non-productive competition in which each group did everything they could to sabotage the performance of their rivals. With the participants seeing every opportunity to speak as a threat that would make their lack of speaking mastery evident, they did not want to take part. This highlights the importance for teachers of establishing a positive or supportive classroom environment if they want to encourage student participation and motivate them in the classroom. As Hannah (2013) states: “If not approached correctly, a classroom can be set up in a way that stifles creativity or does not promote a positive learning environment” (p. 1). As one participant in this study remarks:

What occurs...is that when I participate, some of my classmates make fun of me, they make impolite gestures with their faces and show bad attitudes...sometimes it seems they grumble, they laugh while they look at me during my participations...the class is too divided, the only ones that don’t make fun of you are the ones that are in your own group...they do whatever it takes to sabotage others with the purpose of being the best or the most recognised...I try to stand aside I don’t make fun of anybody. However, I get angry that they always want to sabotage other classmates and when they participate I don’t act in the same way, I don’t even have the desire of speaking. (Interview, Brandon)

Negative Self-Talk

Negative self-talk is a kind of cognitive anxiety (Nolting, 1997). The participants generated negative thoughts about themselves, which affected their performance during oral participation. Although some students revealed that they were confident in their linguistic competence, negative statements about them interfered with their oral production. A participant revealed:

Due to it was a CAE [Cambridge English: Advanced] test that made my nervous be on top...when I am speaking in front of the teacher I usually get nervous, and as I know that CAE is a difficult exam...I thought, I will do it wrong for sure...I don’t have the vocabulary nor the enough knowledge, nor I can’t speak without getting lost for words or choke, nor I understand the British accent. (Interview, Henry)

Corrective Feedback

Corrective feedback refers to the teacher’s response to learners’ errors in oral or written expression (Sheen & Ellis, 2011). Participants in the study revealed their fear of making mistakes due to the possible opinions and reactions of their classmates. Their motivation to speak lessened further because of the way teachers provided corrective feedback when they made mistakes. Aida (1994) suggested that “language teachers can make it possible for anxious students to maximize their language learning by building a nonthreatening and positive learning environment” (p. 164). Some participants stated that their teachers’ attitudes when providing corrective feedback made them feel as if its purpose was for their teachers and classmates to mock them. There were occasions in which they felt corrective feedback was a personal judgment (Arnold, 2007), where it did not matter whether other classmates made more mistakes, as the impolite corrective feedback was focused on them most of the time during which they were constantly teased and laughed at. As one participant describes:

Sometimes it seems that the teacher has something personal against me...when he corrects me...it seems he makes fun of me and my classmates seem to follow him...I try to avoid participating because I don’t like them mocking me. (Interview, Pavel)

Demotivating Factors for Female Participants

Public Speaking Anxiety

The anxiety over one’s speaking in public “can negatively affect students’ academic and interpersonal relationships as it provokes a tendency to withdraw from communication situations” (Swenson, 2011, p. 1). Results from different studies in academic settings have reported that students fear teacher and peer evaluations so they avoid participating in class (Méndez, 2011). Bourhis, Allen, and Bauman (2006) suggest that the stress of trying to “protect one’s grade and not to appear to the teacher or other students as stupid” (p. 212) would lead to these reactions. Participants described not wanting to be mocked because of the mistakes they had made, and being constantly in fear of making mistakes, as their teacher and classmates would think that they were not good enough at English. According to Swenson (2011), “fear of negative evaluation and sensitivity to punishment are both widely accepted reasons for these anxious reactions to public speaking” (p. 3). Participants presented a strong fear of getting a low grade on future exams due to their performance in class, making their oral participation very poor. With students going to great efforts to produce correct utterances, it took too long for them to answer the teacher’s questions. As a result, participants did not speak unless asked. During participation, the students spoke at a low volume, sometimes stuttering and feeling dissatisfied about their performance in speaking activities. One participant reported:

Every time I have to speak in public...as if by magic I forget the words...I don’t like it because I feel that when this happens my classmates and the teacher consider me a bad student...that affects me a lot...I feel frustrated because I can’t speak as fluent as my classmates. (Interview, Carolina)

Peer Evaluation

Horwitz, Horwitz, and Cope (1986) suggest that most students “find foreign language learning, especially in classrooms situations, particularly stressful” (p. 125) because students “fear being less competent than other students or being negatively evaluated by them” (p. 130). Participants compared themselves with classmates when speaking and felt uncomfortable because they thought their classmates were always criticizing their performance when they spoke. Young’s (1990) research on language anxiety revealed that “speaking activities which require ‘on the spot’ and ‘in front of the class’ performance produce the most anxiety from the students’ perspective” (p. 551). Similarly, the participants in this study were anxious at the thought that it was easier for classmates to perceive their mistakes during oral presentations or class participation. Students described feeling comfortable when going unnoticed during class, avoiding as much as possible activities or situations that would bring them to center stage. As one participant explains:

The teacher asked for examples of sentences in Simple Present and Present Continuous in order to learn how to differentiate them. However, I don’t know what happened, since I know the difference but I answered incorrectly. I started feeling anxious when the teacher asked me directly and in addition, everyone was looking at me (Journal, Week 1, Camrin)

Test Anxiety

Test anxiety refers to a “special case of general anxiety consisting of phenomenological, physiological, and behavioral responses” related to a fear of failure (Sieber, 1980, p. 17) and to the “experience of evaluation or testing” (Sieber, 1980, p. 18). Test anxiety is considered beneficial for students because it helps them to be “alert and focused on the task” (Weir, 2008, p. 47). However, high levels of anxiety are negative because they can make students do wrong when answering a test. Participants presented more intense test anxiety in the speaking section, feeling anxious because they did not know how to start the conversation required by the exercise. They stated that they had practiced and studied vocabulary before the exam; however, when teachers assigned the topic they had to talk about, they forgot what they had learned. Participants described feeling frustrated because anxiety affected their oral performance. One participant says:

This week we presented an exam. Honestly, I am not worried about the writing part of the exam, but the oral part causes me a lot of anxiety. I don’t like to fail, and I feel anguish when my grade not only depends on my performance, but also on my partner’s. For example, this time, my partner made mistakes and I realize about them. I got nervous because I didn’t want to make the same error and I blocked myself. Whenever I make a mistake and I see that the teacher takes notes in the evaluation sheet, I don’t want to speak anymore because I know that my grade will be not a good one (Journal, Week 5, Christina)

Lack of Classroom Community

Some participants took English classes not only as part of their English language major, but also at the Self-Study Centre, where they studied with students from different majors offered by the ELT programme and also external students. Thus, these students either knew fellow students or they knew no one at all. Participants described not feeling close to their new classmates or feeling uncomfortable around them. They did not feel motivated to participate due to not having previously interacted with these new classmates. As a result, their participation was very limited. One participant reveals:

I tried to participate as little as possible...I don’t feel in confidence in the classroom since I don’t know any of my classmates...as they are from other majors...I don’t know how they are. (Interview, Paty)

Conclusions

ELT students’ motivation and performance while learning a foreign language are influenced by diverse factors. Male participants demonstrated that they were influenced by more factors than female participants when speaking English. Even though female participants were affected by fewer factors, they experienced them more frequently. Being in a supportive classroom environment is a motivating factor for both male and female students, whereas peer evaluation it is a demotivating one.

Male participants tended to compare their oral performance with that of their classmates, which inhibited their participation or caused them to make mistakes while speaking or producing illogical utterances. Consequently, their participation was not what they expected, which demotivated them. Additionally, female participants reported being afraid of speaking in front of their peers because they felt scrutinized by them. Thus, although the experiences of both male and female participants are comparable with those of their peers, male participants were afraid of being mocked due to their mistakes while women were afraid of being criticized and scrutinized by their peers.

This finding is similar to those of previous studies in the field (Horwitz et al., 1986; Young, 1990). It is important, then, that teachers take action to prevent any mockery in the classroom and make students aware that errors are positive as they highlight the areas students need to work on in order to master the foreign language.

Male participants also described themselves as practicing goal-oriented performances, which pushed them to practice their oral skills and master the content assigned for future participation. Male students seem to be more competitive, based on the descriptions made by participants in this study, in which they state how they felt motivated when able to outperform their peers and thus avoid negative judgment. On the other hand, female participants preferred to practice their oral skills with native speakers when given the opportunity. While female participants tended to use a variety of strategies for practicing their speaking skills, they reported that their confidence increased when interacting with native speakers. Gender identity is directly related to the differential socialization of men and women, whereby women identify themselves using expressive features more than men, while men use instrumentality features more than women (Bem, 1974).

Both male and female participants stated that being in a supportive classroom community was a motivating factor for participating in language class. Thus, it is important that teachers encourage a positive classroom atmosphere in order that students are able to interact with one another and learn from the experience. Given that classroom interactions enable “learners to receive comprehensible input and provide opportunities to negotiate for meaning and produce modified output” (Rassaei & Moinzadeh, 2011, p. 97), the more students interact with one another, the more they will practice and improve their speaking skills.

The feedback provided by teachers can motivate or demotivate students to participate in the classroom. Male and female participants reported that they felt demotivated when given feedback individually in front of their classmates. It seems that participants fear the mockery or criticism an explicit and direct correction can cause, with similar results also found in previous studies (Kitano, 2001; Yan & Horwitz, 2008). Thus, teachers should be sensitive when providing feedback to students with a low EI, as the strategy they decide to use may either encourage or discourage students’ future participation in oral activities.

Male and females differ in the way that they perceive and face situations, and how they regulate their emotions. Emotions have been found to affect students’ motivation, interest, and effort (Meyer & Turner, 2006). Anxiety can make students feel unable to perform well during class or as learners. Anxiety can interfere with students’ motivation and performance because it makes them feel incompetent and lacking in self-confidence, meaning that they “are likely to take more time double-checking their answers or questioning their work before turning it in to their teachers” (Kumavat, 2016, p. 196).

The findings reported in this study highlight the reality that students with a low EI constantly compare themselves with their peers and fear the mockery or criticism to which they can be subject because of mistakes they may make while speaking. Thus, it is paramount that teachers try to create a secure environment in which students feel confident, prevent any mockery immediately, and use classroom activities to reduce students’ anxiety and increase their self-confidence.

1Participants’ excerpts have been translated from Spanish.

2Pseudonyms are used throughout this article to protect participants’ identity.

References

Ames, C. (1992). Classrooms: Goals, structures and students motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(3), 261-271. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.84.3.261.

Arnold, J. (2007). La dimensión afectiva en el aprendizaje de idiomas [The affective dimension in language learning]. Madrid, ES: Edinumen

Barchard, K. A., & Hakstian, A. R. (2004). The nature and measurement of emotional intelligence abilities: Basic dimensions and their relationships with other cognitive ability and personality variables. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 64(3), 437-462. http://doi.org/10.1177/0013164403261762.

Bem, S. L. (1974). The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42(2),155-162. http://doi.org/10.1037/h0036215.

Boonkit, K. (2010). Enhancing the development of speaking skills for non-native speakers of English. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(2), 1305-1309. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.191.

Bora, F. D. (2012). The impact of emotional intelligence on developing speaking skills: From brain-based perspective. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 2094-2098. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.434.

Bourhis, J., Allen, M., & Bauman, I. (2006). Communication apprehension: Issues to consider in the classroom. In B. M. Gayle, R. W. Preiss, N. Burrell, & M. Allen (Eds.), Classroom communication and instructional processes: Advances through meta-analysis (pp. 211-227). Mahwah, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. http://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Camicia, S. P. (2007). Prejudice reduction through multicultural education: Connecting multiple literatures. Social Studies Research and Practice, 2(2), 219-227.

Chapman, M. (2014). Emotional intelligence pocketbook. Alresford, UK: Management Pocketbooks.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behaviour. New York, US: Plenum. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7.

Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1040-1048. http://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.10.1040.

Elliott, E. S., & Dweck, C. S. (1988). Goals: An approach to motivation and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(1), 5-12. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.1.5.

Fernández-Berrocal, P., Alcaide, R., Domínguez, E., Fernández-McNally, C., Ramos, N. S., & Ravira, M. (1998). Adaptación al castellano de la escala rasgo de metaconocimiento sobre estados emocionales de Salovey et al.: datos preliminares. En Libro de Actas del V Congreso de Evaluación Psicológica (pp. 83-84). Málaga, ES.

Hannah, R. (2013). The effect of classroom environment on student learning. Honors Theses, Paper 237. Retrieved from http://scholarworks.wmich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3380&context=honors_theses.

Harumi, S. (2011). Classroom silence: Voices from Japanese EFL learners. ELT Journal, 65(3), 260-269. http://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccq046.

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. Modern Language Journal, 70(2), 125-132. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1986.tb05256.x.

Kitano, K. (2001). Anxiety in the college Japanese language classroom. The Modern Language Journal, 85(4), 549-566. http://doi.org/10.1111/0026-7902.00125.

Kumavat, S. D. (2016). Effective role of emotions in teaching. International Journal of Indian Psychology, 4(1), 196-200.

Littlewood, W. (2000). Do Asian students really want to listen and obey? ELT Journal, 54(1), 31-36. http://doi.org/10.1093/elt/54.1.31.

Lopes, P. N., Brackett, M. A., Nezlek, J. B., Schütz, A., Sellin, I., & Salovey, P. (2004). Emotional intelligence and social interaction. Personality and Psychology Bulletin, 30(8), 1018-1034. http://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204264762.

Mall-Amiri, B., & Hesami, A. (2013). The comparative effect of peer metalinguistic corrective feedback on elementary and intermediate EFL learners’ speaking ability. International Journal of Language Learning and Applied Linguistics World, 4(1), 13-33.

Mayer, J. D., & Salovey, P. (1997). What is emotional intelligence? In P. Salovey & D. J. Sluyter (Eds.), Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Educational implications (pp. 3-31). New York, US: Basic Books.

Méndez, M. G. (2011). The motivational properties of emotions in foreign language learning. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 13(2), 43-59.

Méndez, M. G., & Peña, A. (2013). Emotions as learning enhancers of foreign language learning motivation. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 15(1), 109-124.

Méndez, M. G., & Fabela, M. A. (2014). Emotions and their effects in a language learning Mexican context. System, 42(2), 298-307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2013.12.006.

Meyer, D. K., & Turner, J. C. (2006). Re-conceptualizing emotion and motivation to learn in classroom contexts. Educational Psychology Review, 18(14), 377-390. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-006-9032-1.

Mohammadi, M., & Mousalou, R. (2012). Emotional intelligence, linguistic intelligence, and their relevance to speaking anxiety of EFL learners. Journal of Academic and Applied Studies, 2(6), 11-22.

Nicholls, J. G. (1984). Achievement motivation: Conceptions of ability, subjective experience, task choice, and performance. Psychological Review, 91(3), 328-346. http://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.91.3.328.

Nolting, P. D. (1997). Winning at math: Your guide to learning mathematics through successful study skills. Bradenton, US: Academic Success Press.

Rassaei, E., & Moinzadeh, A. (2011). Investigating the effects of three types of corrective feedback on the acquisition of English Wh-question forms by Iranian EFL learners. English Language Teaching, 4(2), 97-106. http://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v4n2p97.

Rozina, G. (2001). The language of business: Some pitfalls of non-native / native speaker interaction. Studies about Languages, 1,100-104.

Salovey, P., Mayer, J. D., Caruso, D., & Lopes, P. N. (2003). Measuring emotional intelligence as a set of abilities with the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test. In S. J. Lopez & C. R. Snyder (Eds.), Positive psychological assessment: A handbook of models and measures (pp. 251-265). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. http://doi.org/10.1037/10612-016.

Salovey, P., Mayer, J. D., Goldman, S. L., Turvey, C., & Palfai, T. P. (1995). Emotional attention, clarity, and repair: Exploring emotional intelligence using the Trait Meta-Mood scale. In J. Pennebaker (Ed.), Emotion, disclosure, and health (pp. 125-154). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. http://doi.org/10.1037/10182-006.

Shaffer, C. R., & Anundsen, K. (1993). Creating community anywhere: Finding support and connection in a fragmented world. Watertown, US: Penguin Putnam.

Sheen, Y., & Ellis, R. (2011). Corrective feedback in language teaching. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (Vol. 2, pp. 593-610). New York, US: Routledge.

Shumin, K. (2002). Factors to consider: Developing adult EFL students’ speaking abilities. In J. C. Richards & W. A. Renandya (Eds.), Methodology in language teaching: An anthology of current practice (pp. 204-211). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667190.028.

Sieber, J. (1980). Defining test anxiety: Problems and approaches. In I. G. Sarason (Ed.), Test anxiety: Theory, research and applications (pp. 15-42). Hillsdale, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Soodmand Afshar, H., & Rahimi, M. (2014). The relationship among emotional intelligence, critical thinking, and speaking ability of Iranian EFL learners. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 9, 75-79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.05.291.

Swenson, A. (2011). You make my heart beat faster: A quantitative study of the relationship between instructor immediacy, classroom community, and public speaking anxiety. Journal of Undergraduate Research, 14, 1-12.

Tsiplakides, I., & Keramida, A. (2009). Helping students overcome foreign language speaking anxiety in the English classroom: Theoretical issues and practical recommendations. International Education Studies, 2(4), 39-44. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v2n4p39.

Weir, B. S. (2008). Transitions: A guide for the transfer student. Boston, US: Thomson Higher Education.

Wolfradt, U., Felfe, J., & Köster, T. (2002). Self-perceived emotional intelligence and creative personality. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 21(4), 293-310. http://doi.org/10.2190/B3HK-9HCC-FJBX-X2G8.

Woodrow, L. (2006). Anxiety and speaking English as a second language. RELC Journal, 37(3), 308-328. http://doi.org/10.1177/0033688206071315.

Xie, X. (2010). Why are students quiet? Looking at the Chinese context and below. ELT Journal, 64(1),10-20. http://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccp060.

Yan, J. X., & Horwitz, E. K. (2008). Learners’ perceptions of how anxiety interacts with personal and instructional factors to influence their achievement in English: A qualitative analysis of EFL learners in China. Language Learning, 58(1), 151-183. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2007.00437.x.

Young, D. J. (1990). An investigation of students’ perspectives on anxiety and speaking. Foreign Language Annals, 23(6), 539-553. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.1990.tb00424.x.

Zhang, Y. (2009). Reading to speak: Integrating oral communication skills. English Teaching Forum, 47(1), 32-34.

Zhang, X., & Head, K. (2010). Dealing with learner reticence in the speaking class. ELT Journal, 64(1), 1-9. http://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccp018.

About the Authors

Mariza G. Méndez López holds a PhD in Education (University of Nottingham, UK). She is a member of the Mexican National Research System and coordinator of the research group CADICC. Her areas of research are affective factors in foreign language learning and teacher professional development.

Moisés Bautista Tun holds a Bachelor’s degree in ELT (Universidad de Quintana Roo). He currently works in a Mexican high school as an English teacher.

Appendix: Semi-Structured Interview Guide (Adapted From Méndez & Peña, 2013)

- How would you describe your English language learning experience during this first year of the English language major at Universidad de Quintana Roo?

- Has your original motivation changed due to your experience of this first year? How? Why?

- Can you recall some emotional reactions that you experienced during this first year when speaking English?

- Which factors originated those emotional reactions?

- How do you behave when experiencing an emotional reaction?

- Do these emotional reactions interfere with your English classes? How?

- Have some of your emotional reactions influenced your motivation? How?

- Why do you believe this happened?

- Who or what was the responsible for the way you reacted?

- What did you do about those reactions? How did/do you manage them?

- Do you consider that the management of your emotional reactions was important in your motivation to participate in the oral production activities?

- How do you think that your motivation to participate in the oral production activities could have improved?

- Who do you think was responsible for keeping the original motivation with which you began your English language major studies?

- What have you gotten from your participation in this research study?

References

Ames, C. (1992). Classrooms: Goals, structures and students motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(3), 261-271. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.84.3.261.

Arnold, J. (2007). La dimensión afectiva en el aprendizaje de idiomas [The affective dimension in language learning]. Madrid, ES: Edinumen

Barchard, K. A., & Hakstian, A. R. (2004). The nature and measurement of emotional intelligence abilities: Basic dimensions and their relationships with other cognitive ability and personality variables. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 64(3), 437-462. http://doi.org/10.1177/0013164403261762.

Bem, S. L. (1974). The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42(2),155-162. http://doi.org/10.1037/h0036215.

Boonkit, K. (2010). Enhancing the development of speaking skills for non-native speakers of English. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(2), 1305-1309. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.191.

Bora, F. D. (2012). The impact of emotional intelligence on developing speaking skills: From brain-based perspective. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 2094-2098. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.434.

Bourhis, J., Allen, M., & Bauman, I. (2006). Communication apprehension: Issues to consider in the classroom. In B. M. Gayle, R. W. Preiss, N. Burrell, & M. Allen (Eds.), Classroom communication and instructional processes: Advances through meta-analysis (pp. 211-227). Mahwah, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. http://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Camicia, S. P. (2007). Prejudice reduction through multicultural education: Connecting multiple literatures. Social Studies Research and Practice, 2(2), 219-227.

Chapman, M. (2014). Emotional intelligence pocketbook. Alresford, UK: Management Pocketbooks.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behaviour. New York, US: Plenum. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7.

Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1040-1048. http://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.10.1040.

Elliott, E. S., & Dweck, C. S. (1988). Goals: An approach to motivation and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(1), 5-12. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.1.5.

Fernández-Berrocal, P., Alcaide, R., Domínguez, E., Fernández-McNally, C., Ramos, N. S., & Ravira, M. (1998). Adaptación al castellano de la escala rasgo de metaconocimiento sobre estados emocionales de Salovey et al.: datos preliminares. En Libro de Actas del V Congreso de Evaluación Psicológica (pp. 83-84). Málaga, ES.

Hannah, R. (2013). The effect of classroom environment on student learning. Honors Theses, Paper 237. Retrieved from http://scholarworks.wmich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3380&context=honors_theses.

Harumi, S. (2011). Classroom silence: Voices from Japanese EFL learners. ELT Journal, 65(3), 260-269. http://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccq046.

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. Modern Language Journal, 70(2), 125-132. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1986.tb05256.x.

Kitano, K. (2001). Anxiety in the college Japanese language classroom. The Modern Language Journal, 85(4), 549-566. http://doi.org/10.1111/0026-7902.00125.

Kumavat, S. D. (2016). Effective role of emotions in teaching. International Journal of Indian Psychology, 4(1), 196-200.

Littlewood, W. (2000). Do Asian students really want to listen and obey? ELT Journal, 54(1), 31-36. http://doi.org/10.1093/elt/54.1.31.

Lopes, P. N., Brackett, M. A., Nezlek, J. B., Schütz, A., Sellin, I., & Salovey, P. (2004). Emotional intelligence and social interaction. Personality and Psychology Bulletin, 30(8), 1018-1034. http://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204264762.

Mall-Amiri, B., & Hesami, A. (2013). The comparative effect of peer metalinguistic corrective feedback on elementary and intermediate EFL learners’ speaking ability. International Journal of Language Learning and Applied Linguistics World, 4(1), 13-33.

Mayer, J. D., & Salovey, P. (1997). What is emotional intelligence? In P. Salovey & D. J. Sluyter (Eds.), Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Educational implications (pp. 3-31). New York, US: Basic Books.

Méndez, M. G. (2011). The motivational properties of emotions in foreign language learning. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 13(2), 43-59.

Méndez, M. G., & Peña, A. (2013). Emotions as learning enhancers of foreign language learning motivation. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 15(1), 109-124.

Méndez, M. G., & Fabela, M. A. (2014). Emotions and their effects in a language learning Mexican context. System, 42(2), 298-307. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2013.12.006.

Meyer, D. K., & Turner, J. C. (2006). Re-conceptualizing emotion and motivation to learn in classroom contexts. Educational Psychology Review, 18(14), 377-390. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-006-9032-1.

Mohammadi, M., & Mousalou, R. (2012). Emotional intelligence, linguistic intelligence, and their relevance to speaking anxiety of EFL learners. Journal of Academic and Applied Studies, 2(6), 11-22.

Nicholls, J. G. (1984). Achievement motivation: Conceptions of ability, subjective experience, task choice, and performance. Psychological Review, 91(3), 328-346. http://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.91.3.328.

Nolting, P. D. (1997). Winning at math: Your guide to learning mathematics through successful study skills. Bradenton, US: Academic Success Press.

Rassaei, E., & Moinzadeh, A. (2011). Investigating the effects of three types of corrective feedback on the acquisition of English Wh-question forms by Iranian EFL learners. English Language Teaching, 4(2), 97-106. http://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v4n2p97.

Rozina, G. (2001). The language of business: Some pitfalls of non-native / native speaker interaction. Studies about Languages, 1,100-104.

Salovey, P., Mayer, J. D., Caruso, D., & Lopes, P. N. (2003). Measuring emotional intelligence as a set of abilities with the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test. In S. J. Lopez & C. R. Snyder (Eds.), Positive psychological assessment: A handbook of models and measures (pp. 251-265). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. http://doi.org/10.1037/10612-016.

Salovey, P., Mayer, J. D., Goldman, S. L., Turvey, C., & Palfai, T. P. (1995). Emotional attention, clarity, and repair: Exploring emotional intelligence using the Trait Meta-Mood scale. In J. Pennebaker (Ed.), Emotion, disclosure, and health (pp. 125-154). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. http://doi.org/10.1037/10182-006.

Shaffer, C. R., & Anundsen, K. (1993). Creating community anywhere: Finding support and connection in a fragmented world. Watertown, US: Penguin Putnam.

Sheen, Y., & Ellis, R. (2011). Corrective feedback in language teaching. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (Vol. 2, pp. 593-610). New York, US: Routledge.

Shumin, K. (2002). Factors to consider: Developing adult EFL students’ speaking abilities. In J. C. Richards & W. A. Renandya (Eds.), Methodology in language teaching: An anthology of current practice (pp. 204-211). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667190.028.

Sieber, J. (1980). Defining test anxiety: Problems and approaches. In I. G. Sarason (Ed.), Test anxiety: Theory, research and applications (pp. 15-42). Hillsdale, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Soodmand Afshar, H., & Rahimi, M. (2014). The relationship among emotional intelligence, critical thinking, and speaking ability of Iranian EFL learners. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 9, 75-79. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.05.291.

Swenson, A. (2011). You make my heart beat faster: A quantitative study of the relationship between instructor immediacy, classroom community, and public speaking anxiety. Journal of Undergraduate Research, 14, 1-12.

Tsiplakides, I., & Keramida, A. (2009). Helping students overcome foreign language speaking anxiety in the English classroom: Theoretical issues and practical recommendations. International Education Studies, 2(4), 39-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ies.v2n4p39.

Weir, B. S. (2008). Transitions: A guide for the transfer student. Boston, US: Thomson Higher Education.

Wolfradt, U., Felfe, J., & Köster, T. (2002). Self-perceived emotional intelligence and creative personality. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 21(4), 293-310. http://doi.org/10.2190/B3HK-9HCC-FJBX-X2G8.

Woodrow, L. (2006). Anxiety and speaking English as a second language. RELC Journal, 37(3), 308-328. http://doi.org/10.1177/0033688206071315.

Xie, X. (2010). Why are students quiet? Looking at the Chinese context and below. ELT Journal, 64(1),10-20. http://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccp060.

Yan, J. X., & Horwitz, E. K. (2008). Learners’ perceptions of how anxiety interacts with personal and instructional factors to influence their achievement in English: A qualitative analysis of EFL learners in China. Language Learning, 58(1), 151-183. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2007.00437.x.

Young, D. J. (1990). An investigation of students’ perspectives on anxiety and speaking. Foreign Language Annals, 23(6), 539-553. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.1990.tb00424.x.

Zhang, Y. (2009). Reading to speak: Integrating oral communication skills. English Teaching Forum, 47(1), 32-34.

Zhang, X., & Head, K. (2010). Dealing with learner reticence in the speaking class. ELT Journal, 64(1), 1-9. http://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccp018.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Ehsan Namaziandost, Tahereh Heydarnejad, Zeinab Azizi. (2023). To be a language learner or not to be? The interplay among academic resilience, critical thinking, academic emotion regulation, academic self-esteem, and academic demotivation. Current Psychology, 42(20), p.17147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04676-0.

2. Kifayatullah Khan, Yousaf Hayat, Syed Munir Ahmad, Wasal Khan. (2023). A Study of Agriculture Students’ Attitudes towards English Language: A Case Study. Journal of Language and Education, 9(2), p.118. https://doi.org/10.17323/jle.2023.11927.

3. Enisa Mede, Tugce Budak. (2021). Relationship between Emotional Intelligence, Foreign Language Anxiety, and Demotivational Factors in an English Preparatory Language Program. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 24(1), p.6. https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.17859.

4. Sohail Ahmad, Aisha Naz Ansari, Saman Khawaja, Sadia Muzaffar Bhutta. (2023). Research café: an informal learning space to promote research learning experiences of graduate students in a private university of Pakistan. Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education, 14(3), p.381. https://doi.org/10.1108/SGPE-01-2023-0011.

5. Naoko Sano Nakao, Hayo Reinders. (2022). “This Is the End.” A Case Study of a Japanese Learner’s Experience and Regulation of Anxiety. Education Sciences, 12(1), p.25. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12010025.

6. María Daniela Bravo Bailón, Angelica María Santana Bailón, Johanna Bello Piguave, Jhonny Villafuerte Holguín. (2025). Emotional factors and their influence on speaking performance in university students. LATAM Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, 6(4) https://doi.org/10.56712/latam.v6i4.4477.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

Copyright (c) 2017 PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.