Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis of the petrous apex with inner ear involvement: Case report and literature review

Histiocitosis de células de langerhans del ápex petroso con compromiso del oído interno

Palabras clave:

Histiocytosis, Langerhans-Cell, Temporal bone, Ear Neoplasm. (en)Histiocitosis de células de Langerhans, Hueso temporal, Neoplasias del oído. (es)

El compromiso del hueso temporal en la histiocitosis de células de Langerhans (HLC) es el segundo en frecuencia en el área de cabeza y cuello, siendo los sitios de mayor presentación la porción mastoidea y escamosa del hueso. La presentación primaria de la histiocitosis que afecta las estructuras del oído interno es poco frecuente, pues no hay muchos casos reportados en la literatura. En este artículo, se presenta un reporte de caso de compromiso del ápex petroso del temporal en una paciente remitida a la Fundación Hospital de La Misericordia y se realiza una revisión de la literatura para socializar la presentación de la enfermedad, su tratamiento y desenlace.

LANGERHANS CELL HISTIOCYTOSIS OF THE PETROUS APEX WITH INNER EAR INVOLVEMENT

Palabras clave: Histiocitosis de células de Langerhans, Hueso temporal, Neoplasias del oído.

Keywords: Histiocytosis, Langerhans-Cell, Temporal bone, Ear Neoplasm.

Gilberto Eduardo Marrugo Pardo

Otolaryngologist,

Fundación Hospital de La Misericordia

Professor, Universidad Nacional de Colombia

– Department of Surgery –

Otorhinolaryngology Unit

Andrea del Pilar Sierra Ávila

Otolaryngologist

Universidad Nacional de Colombia

Corresponding author:

Gilberto Eduardo Marrugo Pardo

Fundación Hospital de La Misericordia,

Bogotá, D.C. – Colombia.

Email: gmarrugop@unal.edu.co

ABSTRACT

Temporal bone involvement in Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH) is the second most common site of involvement in the head and neck area, with the mastoid and squamous portion of the bone as the most frequent site where LCH manifests. Since there are not many cases reported in the literature, it is possible to state that primary manifestation of histiocytosis affecting the inner ear structures is uncommon. This article reports the case of a patient with involvement of the petrous apex of the temporal bone that was referred to the Fundación Hospital de la Misericordia, and carries out a literature review in order to discuss the manifestation, treatment and outcome of this disease.

INTRODUCTION

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH), known as histiocytosis X until 1985, was first described in 1893 as part of a multisystemic disease that mainly affects population under the age of 16 (1). It is a monoclonal proliferation of dendritic cells with typical Langerhans cells features (2).

LCH is a rare condition with a reported incidence that ranges from 4 to 9 cases per million and its etiology has not yet been established; however, several theories in this regard have been proposed, including those stating LCH has a neoplastic or an immune reaction origin (2). Clinically, LCH may manifest by affecting a single system or organ, being the skeletal system the most frequently compromised, or involving more than two organs (3).

Head and neck areas involvement by LCH ranges from 53% to70%. In these areas, the cranial vault ranks first in terms of involvement by this disease, while the temporal bone comes in second or third place (1-4). On the other hand, the mastoid part of the temporal bone is one of the areas where greater LCH involvement can be observed. Damage of inner ear structures as primary manifestation site is atypical, since there are few cases describing this situation reported in the literature.

CLINICAL CASE

Two years old female referred by a second level health institution due to a four days clinical course of desequiliibrium episodes triggered by changes in the patient’s position with no other symptoms associated. A prior episode of acute otitis media (AOM), with its laterality not specified by her caregivers and treated with antibiotics and analgesia until complete resolution of symptoms, was reported.

Through physical examination it was determined that the patient was in a good general condition, hydrated and afebrile. Left ear otoscopy showed that the patient had detritus in the ear canal and an opaque non-convex tympanic membrane. There was not nystagmus in the vestibular examination, but instability, indifferent lateropulsion and 15 seconds long increase of the support polygon when changing the body position to sitting or standing were observed. Facial symmetry was observed, while no neurological deficit was found. The remaining of the physical examination was within normal limits.

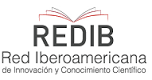

The referring institution sent very poor quality images where a lesion in the left jugular foramen was seen, thus a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the patient’s ears was requested. The CT scan showed the following findings: an osteolytic lesion with complete destruction of the petrous apex, involvement of the internal auditory canal in its entirety, involvement of the basal turn of the cochlea and the posterior semicircular canal, and bone limits variation in both the carotid and jugular canals, which in turn did not allow limits differentiation. Soft tissue occupying the mastoid without bone remodeling or osteolytic lesions were also observed (Figure 1). The cranial nerves magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed an isointense lesion on T1 and T2 with a slight signal increase with the FLAIR sequence. There was not any evidence of vascular involvement by the mass (Figure 1).

Fig 1. CT scan and MRI where it is possible to see an osteolytic lesion compromising the petrous part of the temporal bone with erosion towards the jugular foramen and structures of the inner ear.

Source: Images obtained from the data collected in the study.

Pure-tone audiometry reported a hearing response at 30 dB in open field and specific frequency auditory evoked potentials and absence of V wave in the left ear and preservation of auditory sensitivity in the right ear.

Based on these findings, a diagnostic impression of LCH vs. temporary rhabdomyosarcoma was made. Given the difficult transmastoid access for conducting a biopsy, a middle cranial fossa approach was performed with the cooperation the neurosurgery staff. At an intra-surgical level, a soft tissue mass with similar color of the surrounding healthy bone in the petrous apex of the temporal bone that extended to the internal auditory canal (IAC) was found. Through frozen section biopsy rhabdomyosarcoma diagnosis was temporarily discarded. During surgery, the patient went through pulseless electrical activity while handling the mass, which was easily reverted by the anesthesiology staff.

In the immediate postoperative period the patient developed adrenal insufficiency of critical patients and neurogenic bladder. These conditions were treated medically. A grade V/ VI House-Brackman left peripheral facial paralysis with absence of lacrimation while weeping was reported in the fourth postoperative day.

The official pathology report showed a granulomatous lesion with abundant eosinophils positive for CD-1ª and S100 in immunohistochemistry. The pediatric hematology/ oncology staff confirmed the diagnosis of LCH in its polyostotic monosystemic form affecting the temporal and the sphenoid bones and started a six weeks chemotherapy treatment with vinblastine 6 mg/m2 and prednisone 40 mg/m2.

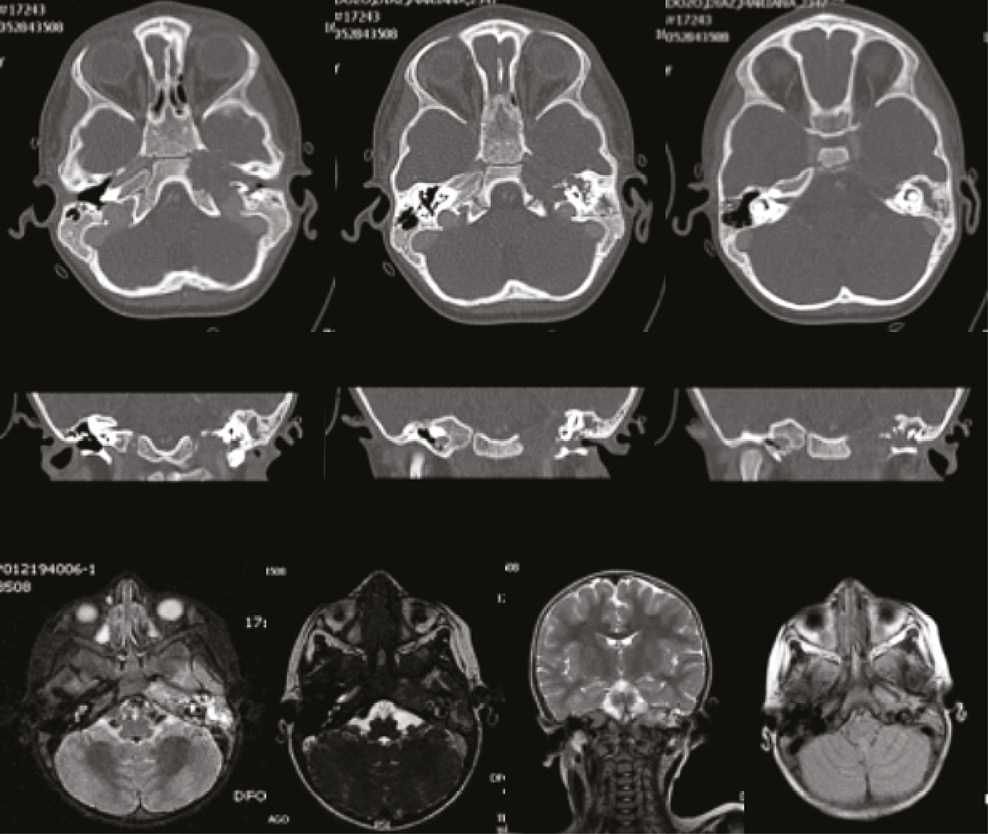

After completing an irregular chemotherapy treatment, control images were obtained. These images showed a significant decrease of the lytic lesion with osteoneogenesis at the affected sites, as well as postsurgical changes (Figure 2). During the final physical examination performed by otolaryngology service, resolution of the instability and persistence of the peripheral facial paralysis were observed.

Fig 2. Six weeks CT scan after chemotherapy showing osteolytic mass resolution, osteoneogenesis and postoperative changes.

Source: Images obtained from the data collected in the study.

DISCUSSION

HCL is a rare disease that mainly affects patients under the age of 16, with subjects between 1 and 4 years old as the most prevalent age group to suffer this condition (5). It has a reported incidence of 4 to 9 cases per million and it can affect any organ or system of the body (2).

According to the current clinical classification proposed by the Histiocytosis Society of the European Society of Hematology and Oncology, HCL can be defined as a disease affecting a single organ or system (monosystemic) or more than one system (multisystemic) (3). In the case of bone involvement, HCL is regarded as monosystemic, even though several bones are affected by the disease (3).

Depending on the number and the systems affected, HCL can be classified under three different conditions with overlapping characteristics, namely:

• Eosinophilic granuloma: Single or multisystem involvement without altering the organ function. It usually occurs in people over 20 years old and it has an excellent prognosis.

• Litterer-Siwe disease: Skin, lymph nodes, lungs and liver involvement. It occurs in patients around three years old. It has a poor prognosis due to multiple organ.

• Hand-Schuller-Christian disease: Anterior pituitary involvement plus diabetes insipidus; exophthalmos and bone involvement. It affects patients between 2 and 3 years old (1).

LCH is a monoclonal proliferation of Langerhans type dendritic cells usually found in skin and lymphoid organs. Its etiology has not yet been elucidated, but two theories have been proposed: one referring to a neoplastic origin, while the other proposes an autoimmune origin (2). In this regard, a family relationship up to 1% of the cases studied with a homocigote concordance of 92% has been found. Likewise, changes in the genome of the cells affected by chromosomal instability, telomere shortening and chromosomal loss of heterogeneity have been reported, which favors neoplastic over autoimmune theory (2).

Pathological diagnosis is made upon detection of cells with Langerhans cell phenotype where macrophages, eosinophils, multinucleated giant cells and T lymphocytes are observed. Diagnosis confirmation is reached when Birbeck granules, tennis racket like cytoplasmic organelles whose creation is induced by langerin, a Langerhans cells C-type lectin transmembrane receptor (6), are identified through electron microscopy. This technique has been recently replaced by CD1 and CD207 positive immunohistochemistry techniques as these markers are key testing elements for C-type lectin receptor (7). The use of such markers provided the confirmation of the pathological diagnosis in this case.

Skin and bone are the systems most affected by LCH, with an involvement of the head and neck areas between 50% and 70% of cases (1,4). In these areas, cranial structures are the most affected, being the cranial vault and the frontal bone the most frequent sites of LCH manifestation, followed by skin, where the condition usually manifests as a vesiculopapular rash that may affect any area of the face or the body (1).

In the United States of America, a study conducted in 22 patients with head and neck areas affected by LCH found a lower average age (five years) and a male preponderance (2:1). However, in this research there were not any statistically significant differences between multisystem or monosystem forms of the disease (7).

Regarding the temporal bone it is possible to say that it is affected in 19% to 25% of cases, with a higher prevalence in children younger than three years old, where the involvement is associated with a multisystem presentation of the disease. According to the literature, in a third of cases, LCH occurs bilaterally and the petrous part is the most affected (5,6).

In a LCH temporal bone Case Report series conducted in Canada it was found that its most frequent manifestation consisted of a mass (70% of the cases), followed by external or otitis media difficult to treat. In 70% of cases unilateral involvement was observed and, in contrast with what it has been reported in the literature, the mastoid region was the site with the highest frequency of involvement, as seen in 70% of cases. Out of the ten patients of the study, eight had LCH multifocal involvement affecting the pituitary or the dura mater (5).

In 2000, Italian researchers conducted a research in a total sample of 250 patients that had been diagnosed with LCH. Out of the 250, 34 had temporal bone involvement; besides, in all of them the disease occurred in its multisystem form. Patients’ average age was 1.8 years; there was not gender preference. Otorrhea was the most common presenting symptom, while LCH diagnosis was only reached after performing several unsuccessful treatments for chronic otitis media (COM) and mastoiditis. In this study, researchers found that patients experiencing ear involvement were younger compared to those without it. In addition, they did not observe any difference in terms of organ dysfunction between both groups, but they noted there was temporal bone involvement with a worse prognosis regarding treatment response and a greater need for a second-line chemotherapy regime (8).

Not a single case report described an inner ear structures primary involvement by LCH, which is probably due to the otic capsule higher resistance to the spreading of the disease. Up to 2008, only 13 cases describing IAC or otic capsule involvement and the resulting sensorineural hearing loss, vestibular symptoms and facial paralysis, which were found in 2.8% of these cases, had been reported (5.9).

It has been stated that up to 10% of cases may present hearing loss, most of them being mixed hearing loss. In a literature review, 19 patients with involvement of the otic capsule or sensorineural hearing loss were found: two cases experiencing invasion of the IAC, a case with involvement of the vestibular aqueduct, nine cases with involvement of the semicircular canals and seven cases with involvement of other regions, all of them related to temporal mastoid injuries as the origin site of the disease (9). Once chemotherapy was finished, researchers reported the following results: regardless of the site of injury, patients with profound hearing loss did not show any hearing improvement; those with severe hearing loss experienced improvement up to mild hearing loss; those with mild hearing loss went back to normal levels of hearing. Based on these results, a hearing loss final sequel in patients with HCL between 7% and 28% was calculated (9).

The involvement of the temporal bone in LCH is not an atypical manifestation, but the involvement of the structures of the inner ear is uncommon.

The clinical picture of the patient, mainly obtained by symptoms of vestibular dysfunction, despite the fact she did not show recurrent AOM, COM or masses in the temporal region, and her age are enough reasons for the physician to carry out a deeper study of the cause of vestibular symptoms, where temporal bone neoplastic lesions should be considered in the diagnostic possibilities. Diagnostic imaging, starting with a CT scan, is an ideal approach when a neoplasm in the temporal bone is suspected. Furthermore, audiological studies appropriate for the patient’s age should be carried out in order to know the patient’s baseline auditory profile prior to surgical or medical treatment and evaluate the hearing prognosis depending on the disease.

Pediatric otolaryngologists must have access to all the tools necessary to perform tissue sampling, whether this is done via a transmastoid approach or, as it happened in this case, through a middle fossa approach, since histopathologic diagnosis is fundamental to start an appropriate medical treatment.

The treatment of patients with LCH should always take place in an interdisciplinary context where the oncology staff has a main role in the implementation of the appropriate chemotherapy regime and the monitoring of the disease in conjunction with imaging and audiological control.

CONCLUSION

Otologic pathology in pediatric population is not limited to disorders related to Eustachian tube and different types of otitis media. The involvement of the temporal bone by neoplastic lesions should be considered in patients with AOM difficult to manage, including LCH.

However, rare presentations of the disease that come along with vestibular symptoms and sensorineural hearing disorders should be taken into account for a proper study and treatment of the disease, since these should raise suspicion of involvement of the structures of the inner ear. The patient reported in this case showed involvement of the inner ear with profound hearing loss in the monosystem form of LCH, an unusual form of presentation that made necessary a different diagnostic approach.

REFERENCES

1.Nicollas R, Rome A, Belaïch H, Roman S, Volk M, Gentet JC, et al. Head and neck manifestation and prognosis of Langerhans’cell histiocytosis in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74(6):669-73. http://doi.org/dmn22c.

2.Abla O, Egeler RM, Weitzman S. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: Current concepts and treatments. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36(4):354-9. http://doi.org/fgnnt9.

3.Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, Schäfer E, Nanduri V, Jubran R, et al. Langerhans cell Histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work-up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(2):175-84. http://doi.org/bp88.

4.Cochrane LA, Prince M, Klarke K. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis in the paediatric population: presentation and treatment of head and neck manifestations. J Otolaryngol. 2003;32(1):33-7.

5.Saliba I, Sidani K, El Fata F, Arcand P, Quintal MC, Abela A. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the temporal bone in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;72(6):775-86. http://doi.org/cprrjv.

6.Nelson BL. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis of the temporal bone. Head Neck Pathol. 2008;2(2):97- 8. http://doi.org/fph8wx.

7.Buchmann L, Emami A, Wei JL. Primary head and neck Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135(2):312-17. http://doi.org/ffsdd4.

8.Surico G, Muggeo P, Muggeo V, Conti V, Novielli C, Romano A, et al. Ear involvement in childhood Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis. Head Neck. 2000;22(1):42-7. http://doi.org/bzqb9n.

9.Saliba I, Sidani K. Prognostic indicators for sensorineural hearing loss in temporal bone histiocytosis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73(12):1616-20. http://doi.org/ddpmzb.

HISTIOCITOSIS DE CÉLULAS DE LANGERHANS DEL ÁPEX PETROSO CON COMPROMISO DEL OÍDO INTERNO

Palabras clave: Histiocitosis de células de Langerhans, Hueso temporal, Neoplasias del oído.

Keywords: Histiocytosis, Langerhans-Cell, Temporal bone, Ear Neoplasm.

Gilberto Eduardo Marrugo Pardo

Otorrinolaringólogo,

Fundación Hospital de La Misericordia

Profesor Titular Universidad Nacional de Colombia

– Departamento de Cirugía –

Unidad de Otorrinolaringología

Andrea del Pilar Sierra Ávila

Otorrinolaringóloga

Universidad Nacional de Colombia

Correspondencia:

Gilberto Eduardo Marrugo Pardo

Fundación Hospital de La Misericordia,

Bogotá, D.C. – Colombia.

Correo electrónico: gmarrugop@unal.edu.co

RESUMEN

El compromiso del hueso temporal en la histiocitosis de células de Langerhans (HLC) es el segundo en frecuencia en el área de cabeza y cuello, siendo los sitios de mayor presentación la porción mastoidea y escamosa del hueso. La presentación primaria de la histiocitosis que afecta las estructuras del oído interno es poco frecuente, pues no hay muchos casos reportados en la literatura. En este artículo, se presenta un reporte de caso de compromiso del ápex petroso del temporal en una paciente remitida a la Fundación Hospital de La Misericordia y se realiza una revisión de la literatura para socializar la presentación de la enfermedad, su tratamiento y desenlace.

INTRODUCCIÓN

La histiocitosis de células de Langerhans (HCL), conocida como Histiocitosis X hasta 1985, fue descrita por primera vez en 1893 como parte de una patología multisistémica que afecta principalmente a población menor de 16 años (1). Consiste en una proliferación monoclonal de células dendríticas con las características típicas de las células de Langerhans (2).

La HCL es una rara patología con una incidencia reportada que varía entre 4 a 9 por millón de personas y cuya etiología aún no ha sido establecida; sin embargo, varias teorías se han planteado, entre ellas las de origen neoplásico y por reacción inmunitaria (2). Clínicamente, se puede presentar con compromiso de un único sistema u órgano, siendo el más frecuente el sistema esquelético, o de forma multisistémica, con más de dos órganos comprometidos (3).

El compromiso en las áreas de cabeza y cuello varía entre el 53% y el 70%, siendo el sitio más frecuente la calota, mientras que el hueso temporal se reporta entre el segundo y el tercer lugar (1-4). Del hueso temporal, la región mastoidea es uno de los sitios con mayor compromiso por parte de la enfermedad, siendo atípica la lesión de las estructuras en el oído interno como sitio primario, ya que hay pocos reportes de caso en la literatura.

CASO CLÍNICO

Paciente femenina de dos años de edad remitida del segundo nivel de atención por cuadro de cuatro días de evolución consistente en episodios de desequilibrio de pocos segundos de duración, únicamente con los cambios de posición, sin otros síntomas asociados. Se reporta antecedente de episodio de otitis media aguda (OMA), de lateralidad no especificada por los cuidadores, manejada con antibioticoterapia y analgesia con resolución completa de los síntomas. No se informan otros antecedentes de importancia.

Al realizar el examen físico se encuentra que la paciente está en buenas condiciones generales, hidratada, afebril y presenta otoscopia izquierda con detritus en conducto auditivo externo y membrana timpánica opaca, no abombada. Examen vestibular sin presencia de nistagmus, con inestabilidad, lateropulsión indiferente y aumento del polígono de sustentación con el cambio del decúbito a la sedestación o bipedestación de 15 segundos de duración. Se evidencia simetría facial, ningún déficit neurológico; resto del examen físico está dentro de límites normales.

Del lugar de remisión envían imágenes de muy mala calidad en las que impresiona una lesión a nivel de agujero yugular izquierdo, por lo que se solicita tomografía computarizada de oídos contrastada, la cual muestra una lesión osteolítica con destrucción completa del ápex petroso; compromiso del conducto auditivo interno en toda su extensión, con erosión; compromiso de la vuelta basal de la cóclea y del canal semicircular posterior, y alteración en los límites óseos del canal carotideo y yugular sin lograr diferenciar límites. También se evidencia ocupación por material de tejidos blandos y mastoides sin remodelación ósea ni lesiones osteolíticas a este nivel (Figura 1). La resonancia magnética nuclear de pares craneanos muestra una lesión isointensa en t1 y t2 con leve aumento de señal con la secuencia FLAIR, no hay evidencia de compromiso vascular con la masa (Figura 1).

Fig 1. TAC y RNM en las que se evidencia lesión osteolítica que compromete tiendo el ápex temporal con erosión hacia el agujero yugular y las estructuras del oído interno.

Fuente: Documento obtenido durante la realización del estudio.

La audiometria tonal comportamental reportó una respuesta auditiva a 30 dB a campo abierto y potenciales evocados auditivos de frecuencia específica, con ausencia de ondas en el oído izquierdo y sensibilidad auditiva derecha conservada.

Con estos hallazgos se realizó una impresión diagnóstica de HCL vs. rabdomiosarcoma temporal y, dado el difícil acceso transmastoideo para la toma de biopsia, se hizo un abordaje por fosa media en conjunto con el servicio de neurocirugía.

Intraquirúrgicamente se evidenció una lesión blanda, eucrómica con el hueso sano circundante en ápex temporal extendiéndose posterior al conducto auditivo interno (CAI) La biopsia por congelación excluyó temporalmente el diagnóstico de rabdomiosarcoma. La paciente presentó actividad eléctrica sin pulso durante la manipulación de la masa, fácilmente reversada por el equipo de anestesiología.

En el posoperatorio inmediato, la paciente desarrolla insuficiencia suprarrenal del paciente crítico y vejiga neurogénica, condiciones que se trataron médicamente. Al cuarto día posoperatorio se documenta parálisis facial periférica izquierda House-Brackman de V/VI con

ausencia de lagrimeo durante el llanto.

La patología oficial reportó una lesión granulomatosa con abundantes eosinófilos positivos para CD-1ª y S100 en la inmunohistoquímica. El grupo de hemato-oncología pediátrica confirmó el diagnóstico de histiocitosis de células de Langerhans monosistémica poliostótica por compromiso de temporal y esfenoides e inició manejo quimioterapéutico con vinblastina a 6 mg/ m2 y prednisona 40 mg/m2 por seis semanas. Al concluir el manejo quimioterapéutico irregular se tomaron imágenes de control que evidenciaron una importante disminución de la lesión lítica con osteoneogénesis de los sitios afectados y cambios posquirúrgicos (Figura 2). En el examen físico de última valoración, realizado por el servicio de otorrinolaringología, se observó resolución de la inestabilidad y persistencia de la parálisis facial periférica.

Fig 2. TAC de control de seis semanas posterior a quimioterapia con resolución de la masa osteolítica, osteoneogénesis y cambios posoperatorios.

Fuente: Documento obtenido durante la realización del estudio.

DISCUSIÓN

La HLC es una rara patología que principalmente afecta a pacientes menores de 16 años, con un pico entre los 1 y 4 años de edad (5). Tiene una incidencia reportada de 4 a 9 casos por millón de personas y puede afectar cualquier órgano o sistema del cuerpo (2).

La clasificación clínica actual, propuesta por la Sociedad de Histiocitosis de las Sociedades Europeas de Hematología y Oncología, se da por una enfermedad con afección a un único órgano o sistema (monosistémica) y por compromiso de más de un sistema (multisistémica) (3); en el caso de compromiso del hueso se considera mososistémica, así varios huesos estén comprometidos por la enfermedad (3).

Dependiendo del número y de los sistemas afectados, la enfermedad también puede agruparse bajo el nombre de tres entidades diferentes con características superpuestas, a saber:

• Granuloma eosinofílico: compromiso uni o múltisistémico sin alteración en la función del órgano. Generalmente se presenta en mayores de 20 años y tiene un excelente pronóstico.

• Enfermedad de Litterer-Siwe: compromiso de la piel, los nodos linfáticos, el pulmón y el hígado, con una edad de presentación aproximada a los tres años. Pobre pronóstico debido a disfunción multiorgánica.

• Enfermedad de Hand-Schuller Christian: compromiso de la hipófisis anterior con diabetes insípida, compromiso óseo y exoftalmos. Afecta a pacientes entre los 2 y 3 años (1).

La HLC consiste en una proliferación monoclonal de células dendríticas tipo células de Langerhans encontradas normalmente en la piel y en los órganos linfáticos. Su etiología no ha sido esclarecida, pero dos teorías se han planteado: una neoplásica y otra autoinmune (2). Al respecto, se ha encontrado una relación familiar hasta en el 1% de los casos estudiados, con una tasa de concordancia en pacientes homocigóticos del 92%; así mismo, se han documentado alteraciones en el genoma de las células afectadas con inestabilidad cromosómica, acortamientos teloméricos y pérdida de heterogenicidad cromosómica, lo que favorece la teoría neoplásica sobre la autoinmune (2).

El diagnóstico patológico se realiza ante la detección de células con fenotipo de células de Langerhans con presencia de macrófagos, eosinófilos, células gigantes multinucleadas y linfocitos T. La confirmación se hace mediante microsocopía electrónica con la identificación de los gránulos de Birbeck, organelos citoplasmáticos en forma de raqueta de tenis cuya formación está inducida por la langerina, un receptor transmembrana tipo lectina C de las células de Langerhans (6). Esta técnica ha sido reemplazada recientemente por técnicas de inmunohistoquímica con positividad para CD1 y CD207, siendo estos marcadores las pruebas de oro para el receptor de lectina tipo C (7). El uso de estos marcadores otorga la confirmación para el diagnóstico patológico de este caso.

Los sitios más frecuentes de compromiso son la piel y el hueso, afectando el área de cabeza y cuello entre el 50% y el 70% de los casos (1,4). En estas áreas, el sitio de mayor compromiso corresponde a las estructuras craneanas, con la calota y el hueso frontal como primeros lugares de presentación, seguidos de la piel, donde generalmente se manifiesta como un rash vesiculopapular que puede afectar cualquier zona de la cara y el cuerpo (1).

Un estudio realizado en Estados Unidos en 22 pacientes con compromiso en el área de cabeza y cuello encontró una menor edad promedio (cinco años) y una preponderancia en el sexo masculino (2:1). Sin embargo, no se observó una diferencia estadísticamente significativa entre la enfermedad multisistémica o monosistémica cuando se presentaba en esta localización (7).

En cuanto al hueso temporal, es posible decir que está comprometido del 19% al 25% de los casos, teniendo mayor frecuencia en niños menores de tres años, asociado a presentación multisistémica de la enfermedad. En un tercio de los casos se presenta de forma bilateral y la porción mayormente afectada es la petrosa, según lo reportado en la literatura (5,6).

En una revisión de casos de HCL del temporal realizada en Canadá, se encontró que la manifestación más frecuente fue la de una masa a nivel del temporal, con un 70% de los casos, seguida de otitis medias o externas de difícil manejo. En el 70% de los casos se observó compromiso unilateral y, a diferencia de lo reportado en la literatura, el sitio de mayor compromiso fue la región mastoidea, también en un 70% de los casos. Ocho de los diez pacientes presentaron compromiso multifocal con afectación de hipófisis o duramadre (5).

En el 2000, investigadores italianos llevaron a cabo un estudio con un total de 250 pacientes diagnosticados con HCL, 34 de los cuales tenían compromiso del hueso temporal, todos dentro de la forma multisistémica de la enfermedad. La edad promedio fue de 1.8 años, sin preferencia en el sexo del paciente. El síntoma más frecuente de presentación fue la otorrea y el diagnóstico se dio posterior a varios tratamientos fallidos para otitis media crónica (OMC) y mastoiditis. En el estudio se encontró que los pacientes con compromiso de oído eran más jóvenes en comparación con aquellos sin compromiso; no observaron diferencias en la disfunción orgánica entre estos dos grupos, pero sí un compromiso a nivel temporal con un peor pronóstico en cuanto a la respuesta al tratamiento y una mayor necesidad de una segunda línea de quimioterapia (8).

En ninguno de los reportes de caso se encontró compromiso primario de las estructuras del oído interno, probablemente por la mayor resistencia ofrecida por la cápsula ótica para la diseminación de la enfermedad. Hasta el 2008, solo 13 casos habían sido reportados con compromiso del CAI o cápsula ótica con la consiguiente hipoacusia neurosensorial, síntomas vestibulares y parálisis facial, los cuales fueron reportados en un 2.8% de estos casos (5,9).

Se ha reportado que hasta el 10% de los casos pueden cursar con hipoacusia, la mayoría siendo hipoacusias mixtas. En una revisión de la literatura se reportaron 19 pacientes con compromiso de la cápsula ótica o hipoacusia neurosensorial: dos casos con invasión del CAI, un caso con compromiso del acueducto vestibular, nueve casos con compromiso de los canales semicirculares y el resto con compromiso en otros sitios, siempre asociados a otras lesiones temporomastoideas como sitio de origen de la enfermedad (9). Posterior al manejo quimioterapéutico se observó que los pacientes que debutaron con hipoacusias profundas no tuvieron mejorías auditivas posteriores, independientemente del sitio de la lesión, que quienes lo hicieron con hipoacusia severa tuvieron una mejoría que iba hasta el rango de moderada y que quienes debutaron con una hipoacusia moderada retornaron a niveles normales de audición, calculando una secuela final de hipoacusia en los pacientes con HCL entre el 7% y el 28% (9).

El compromiso del hueso temporal dentro de la HCL no es una manifestación atípica, sin embargo el compromiso de las estructuras del oído interno sí lo es.

El cuadro clínico de la paciente, dado principalmente por síntomas de disfunción vestibular, a pesar de que no presentara OMA a repetición, OMC o masas en la región temporal, y teniendo en cuenta su edad, siempre debe llevar al médico a investigar de forma más profunda la causa de los síntomas vestibulares, considerando lesiones neoplásicas del temporal dentro de las posibilidades diagnósticas. La toma de imágenes diagnósticas, empezando con una tomografía, es ideal ante la sospecha de neoplasias del temporal, al igual que los estudios audiológicos apropiados para la edad del paciente, para conocer el estado basal previo al tratamiento quirúrgico o médico y poder evaluar el pronóstico auditivo según la enfermedad.

El otorrinolaringólogo pediátrico debe contar con todas las herramientas para tomar muestras de tejido, ya sea a través de vía transmastoidea o, como en este difícil caso, de un abordaje por fosa media, ya que el diagnóstico histopatológico es invaluable para dar inicio al tratamiento médico adecuado.

El tratamiento del paciente siempre debe ocurrir en un contexto interdisciplinario con el grupo de oncología, como uno de los actores principales para llevar a cabo el régimen quimioterapéutico adecuado y el seguimiento de la enfermedad en conjunto con control imagenológico y audiológico.

CONCLUSIÓN

La patología otológica en población pediátrica no se limita a trastornos relacionados con la trompa de Eustaquio y los diferentes tipos de otitis media. El compromiso por lesiones neoplásicas del temporal debe tenerse en cuenta en aquellos pacientes con OMA de difícil manejo, incluyendo a la HCL.

Sin embargo, se deben considerar las presentaciones raras de la enfermedad con síntomas vestibulares y alteraciones auditivas neurosensoriales que deben despertar la sospecha de compromiso de las estructuras del oído interno para su adecuado estudio y manejo. La paciente reportada en este caso presentaba afección de oído interno con hipoacusia profunda en enfermedad monosistémica, una forma inusual de presentación que planteó un diferente abordaje diagnóstico.

REFERENCIAS

1.Nicollas R, Rome A, Belaïch H, Roman S, Volk M, Gentet JC, et al. Head and neck manifestation and prognosis of Langerhans’cell histiocytosis in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74(6):669-73. http://doi.org/dmn22c.

2.Abla O, Egeler RM, Weitzman S. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: Current concepts and treatments. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36(4):354-9. http://doi.org/fgnnt9.

3.Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, Schäfer E, Nanduri V, Jubran R, et al. Langerhans cell Histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work-up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(2):175-84. http://doi.org/bp88.

4.Cochrane LA, Prince M, Klarke K. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis in the paediatric population: presentation and treatment of head and neck manifestations. J Otolaryngol. 2003;32(1):33-7.

5.Saliba I, Sidani K, El Fata F, Arcand P, Quintal MC, Abela A. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the temporal bone in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;72(6):775-86. http://doi.org/cprrjv.

6.Nelson BL. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis of the temporal bone. Head Neck Pathol. 2008;2(2):97- 8. http://doi.org/fph8wx.

7.Buchmann L, Emami A, Wei JL. Primary head and neck Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135(2):312-17. http://doi.org/ffsdd4.

8.Surico G, Muggeo P, Muggeo V, Conti V, Novielli C, Romano A, et al. Ear involvement in childhood Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis. Head Neck. 2000;22(1):42-7. http://doi.org/bzqb9n.

9.Saliba I, Sidani K. Prognostic indicators for sensorineural hearing loss in temporal bone histiocytosis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73(12):1616-20. http://doi.org/ddpmzb.

Referencias

Nicollas R, Rome A, Belaïch H, Roman S, Volk M, Gentet JC, et al. Head and neck manifestation and prognosis of Langerhans'cell histiocytosis in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74(6):669-73. http://doi.org/dmn22c

Abla O, Egeler RM, Weitzman S. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: Current concepts and treatments. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36(4):354-9. http://doi.org/fgnnt9

Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, Schäfer E, Nanduri V, Jubran R, et al. Langerhans cell Histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work-up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(2):175-84. http://doi.org/bp88

Cochrane LA, Prince M, Klarke K. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis in the paediatric population: presentation and treatment of head and neck manifestations. J Otolaryngol. 2003;32(1):33-7

Saliba I, Sidani K, El Fata F, Arcand P, Quintal MC, Abela A. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the temporal bone in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;72(6):775-86. http://doi.org/cprrjv

Nelson BL. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis of the temporal bone. Head Neck Pathol. 2008;2(2):97-8. http://doi.org/fph8wx

Buchmann L, Emami A, Wei JL. Primary head and neck Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135(2):312-17. http://doi.org/ffsdd4

Surico G, Muggeo P, Muggeo V, Conti V, Novielli C, Romano A, et al. Ear involvement in childhood Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis. Head Neck. 2000;22(1):42-7. http://doi.org/bzqb9n

Saliba I, Sidani K. Prognostic indicators for sensorineural hearing loss in temporal bone histiocytosis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73(12):1616-20. http://doi.org/ddpmzb

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Visitas a la página del resumen del artículo

Descargas

Licencia

Derechos de autor 2016 Case reports

Esta obra está bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivadas 4.0.

Los autores al someter sus manuscritos conservarán sus derechos de autor. La revista tiene el derecho del uso, reproducción, transmisión, distribución y publicación en cualquier forma o medio. Los autores no podrán permitir o autorizar el uso de la contribución sin el consentimiento escrito de la revista.

El Formulario de Divulgación Uniforme para posibles Conflictos de Interés y los oficios de cesión de derechos y de responsabilidad deben ser entregados junto con el original.

Aquellos autores/as que tengan publicaciones con esta revista, aceptan los términos siguientes:

Los autores/as conservarán sus derechos de autor y garantizarán a la revista el derecho de primera publicación de su obra, el cual estará simultáneamente sujeto a la Licencia de reconocimiento de Creative Commons 4.0 que permite a terceros compartir la obra siempre que se indique su autor y su primera publicación en esta revista.

Los autores/as podrán adoptar otros acuerdos de licencia no exclusiva de distribución de la versión de la obra publicada (p. ej.: depositarla en un archivo telemático institucional o publicarla en un volumen monográfico) siempre que se indique la publicación inicial en esta revista.

Se permite y recomienda a los autores/as difundir su obra a través de Internet (p. ej.: en archivos telemáticos institucionales o en su página web) antes y durante el proceso de envío, lo cual puede producir intercambios interesantes y aumentar las citas de la obra publicada. (Véase El efecto del acceso abierto).