Non-native children reading in English: Types of miscues and the L1 influence revisited

Keywords:

Reading aloud, reading miscues or errors, good and poor readers (en)lectura en voz alta, errores de lectura, buenos malos lectores (es)

Downloads

Non-native children reading in English: Types of miscues and the L1 influence revisited

Dr. Ilona Huszti*

II. Rákóczi Ferenc Transcarpathian Hungarian College of Higher Education, Ukraine

*ilonahuszti@gmail.com, Dr. Ilona Huszti has been working in tertiary education for 13 years. She is training pre-service English teachers. Her research interests include oral reading and reading miscues in the foreign language classroom, reading comprehension, and teacher training. Now, she is working on the improvement of the teaching practicum of her college students.

This paper reports the findings of a case study that investigated the reading errors or miscues made by young EFL learners. These learners were native speakers of Hungarian or Ukrainian. The hypothesis was that there is a difference between the miscues made by Hungarian and Ukrainian learners when reading aloud in English because of the influence of their first language (Hungarian belongs to the Finno-Ugrian language family, while Ukrainian belongs to the Indo-European one; the two languages have different orthographies â Roman and Cyrillic). The research focused on three types of reading miscues: phonetic, lexical and grammatical. Results show that Hungarian learners made less mistakes than Ukrainian ones. This is mainly due to the mother tongue influence on the foreign language.

Key words: Reading aloud, reading miscues or errors, good and poor readers

Este trabajo presenta los hallazgos de un estudio de caso que se basó en los errores de lectura cometidos por jóvenes estudiantes de EFL. Estos alumnos eran hablantes nativos de húngaro o ucraniano. La hipótesis es que existe una diferencia entre los errores cometidos por los estudiantes húngaros y ucranianos en la lectura en voz alta en inglés debido a la influencia de su lengua materna (el húngaro pertenece a la familia finougria, mientras que el ucraniano pertenece a la familia indo-europea; los dos idiomas tienen diferentes ortografías â el alfabeto romano y el cirílico). La investigación se centró en tres tipos de errores de lectura: fonéticos, léxicos y gramaticales. Los resultados muestran que los estudiantes húngaros cometieron menos errores que los ucranianos. Esto se debe principalmente a la influencia de la lengua materna en la lengua extranjera.

Palabras clave: lectura en voz alta, errores de lectura, buenos y malos lectores

Este artículo se recibió en julio 11, 2009 y fue aceptado para publicación en octubre 25, 2009

Introduction

The research described in this paper was carried out among eleven-year-olds in a bilingual context. The learners were native Hungarian and Ukrainian children who studied English as a foreign language (EFL) in Berehovo, a small provincial town in the south-west of Ukraine. The population of the town is multi-national and multi-lingual. The various languages of the nations living side by side have evident impact on each other (Bárány, 2005). The main aim of conducting the investigation was to obtain empirical evidence whether the two languages also influence the acquisition of a third one when learners learn a language as a foreign one.

The hypothesis was that the mother tongues of the learners did have impacts on the process during which they acquired English language reading skills. Based on this hypothesis, the research questions were formulated:

- What miscues do young Ukrainian and Hungarian learners make when reading aloud in English?

- What might account for these miscues?

- What are the differences between good and poor readers in terms of quantity and quality of miscues?

To gain additional information on the way the learners read in English in the classroom, their English teachers were interviewed about the reading techniques and tasks in the lessons, their frequency, etc.

Theoretical Considerations

Reading as a Language Skill

Chastain determines reading as a receptive skill because the person who reads a written text is receiving a message from the one who has written the text. Various authors have also referred to reading as a decoding skill, which terminology derives from “the idea of language as a code, one which must be deciphered to arrive at the meaning of the message” (Chastain, 1988, p. 216).

There are various kinds of reading, e.g. silent and oral reading, analytical and syntactic reading, etc. (Stronin, 1986). The current study deals with oral reading. It is a type of reading during which the reader pronounces a written text (Sztanáné Babits, 2001). It is a bottom-up approach to the reading process (Urquhart & Weir, 1998) which means that “the reader begins with the printed word, recognizes graphic stimuli, decodes them to sound, recognizes words and decodes meaning” (Alderson, 2000, p. 16).

The bottom-up approach is associated with 'phonics' approaches to the teaching of reading, stating that first the recognition of letters (and the identification of the sounds they correspond to) must be learned by children before they can read words, phrases and sentences (Alderson, 2000). Reading aloud is mentioned in the academic literature as an assessment technique by which reading is tested or checked (see Fordham, Holland & Millican, 1995; Alderson, 2000), while other researchers attach importance to it in a different way. Panova (1989) says that reading a text aloud is important for maintaining and perfecting the pronouncing skills of the learners. It helps overcome psychological barriers and fear of starting to speak in a foreign language. Panova considers that by means of oral reading it is possible to master the sound system of a foreign language and it strengthens the phonetic ability to re-code signals at the letter level, as well as at the level of word, sentence and text. She believes that at the elementary stage reading aloud is an important means to develop a reading technique, while at the advanced level of language learning it mainly plays the role of control or expressive reading.

Good and Poor Readers

In the literature about reading processes, readers are divided into good or successful readers and poor, or weaker, or unsuccessful ones. Sometimes they are also called fluent and less fluent readers (Alderson, 2000). One distinguishing feature between these two categories of readers is the use of reading strategies. Good readers use strategies flexibly. Among such strategies Alderson includes “recognising the more important information in text, adjusting reading rate, skimming, previewing, using context to resolve a misunderstanding, formulating questions about information, monitoring cognition” (2000, p. 60).

Although poor readers might possess the strategies mentioned above, they do not frequently know when and how to apply them. This is not surprising because studies on strategies used by unsuccessful second language learners revealed the same results (Vann & Abraham, 1990). Poor readers also differ from good ones in poor phonetic decoding, intensivity to word structures and poor encoding of syntactic properties (Vellutino & Scanlon, 1987, in Alderson, 2000). Six component parts in the fluent reading process are suggested by Grabe (1991): automatic recognition skills, vocabulary and structural knowledge, formal discourse structure knowledge, content/world background knowledge, synthesis and evaluation skills/strategies, metacognitive knowledge and skills monitoring.

Based on recent accounts of the fluent reading process, one can conclude that fluent reading is rapid and purposeful; it is flexible and develops gradually (Alderson, 2000).

Reading ‘Errors’ or Miscues Made By Foreign Language Learners

It is generally accepted that both good and poor readers make errors when reading. These errors are present in the silent reading process, but they are more distinguished when reading aloud. A reading error is the violation of speech communication by means of printed text (Wallace, 1992). Such errors are also referred to as miscues (Goodman & Burke, 1973). These errors occurring in the process of loud reading cannot be considered errors at all because, as Goodman and Goodman (1978) indicate, the term ‘error’ has a negative connotation in education. Therefore, they prefer to use the term ‘miscue’ suggesting that the response to the written text uttered by the reader is not necessarily erroneous. Rather, it can show how the reader processes information obtained via visual input.

Thus, for the purposes of the present study the construct of a reading miscue was defined as a case when during loud reading the reader’s response to the text (i.e. observed response) differs from what is actually printed on the paper (i.e. expected response). Reading miscues can be approached from different angles, e.g. linguistic and psychological. From the linguistic point-of-view, Klychnikova (1972, 2003) groups miscues into three categories: phonetic, lexical and grammatical.

Phonetic miscues show violation in the pronunciation of separate sounds, words, word combinations and sentences. They may be especially noticed when reading aloud, though they may occur during silent reading, too. From time to time they are connected with violation of meaning. At the same time, the visual image of a word in most cases has a stronger effect than its pronunciation; therefore, there is no violation of meaning. For instance, the learner reads the phrase ‘The pen is on the table’. Incorrect articulation of sound [p] in the word ‘pen’ does not lead to incorrect understanding of the concrete meaning of the given phrase, because for the learner the visual image of the word ‘pen’ is closely connected with its meaning. Even if we speak about loud reading, this is of importance only for the listener, and not for the reader.

The case is the same with incorrect intonation of the phrase ‘Is this a big dog?’ It does not cause any difficulty in loud or silent reading either, as it is graphically marked by the question mark acquired by the learner visually (Klychnikova, 1972).

A typical phonetic miscue is when the ending of regular verbs in the past simple (-ed) following voiceless consonants is read as [id] instead of [t], e. g. instead of [laikt] students read [’laikid]. At the beginner and elementary levels pupils very often change the sequence of sounds in a word, e. g. the word ‘big’ is read as ïgibï, the word ‘dog’ is read as [god]. The reasons for these miscues are various ranging from eagerness to pronounce words, phrases and sentences faster to interference of the mother-tongue on the foreign language learners.

Lexical miscues occur when students replace one word by another when reading. Such examples were observed by Klychnikova (1972): reading ‘river’ instead of ‘winter’, ‘bathroom’ instead of ‘birthday’, etc. Goodman and Burke (1973) call this type of reading miscues ‘substitution miscues’.

Reading miscues belonging to the grammatical type can be frequently observed when reading aloud. They are of different nature:

- Agreement or concord between the subject and the predicate (a typical ‘problem’ here is omission of ending ‘-s’ of the verb in the present simple third person singular), e. g. ‘She plays with her sister’ is read as ‘She play with her sister’;

- Omission of plural ending of nouns, e. g. ‘There are roses and daffodils there’ is read as ‘There are rose and daffodil there’;

- Reading the English definite and indefinite articles. The most common miscues while speaking about article are that students do not read it, replace the definite article with the indefinite one, or add an article where there is not any, e.g. ‘There are chairs in the room’ is read as ‘There are a chairs in room’;

- Incorrect reading of verb tenses (e.g. sequence of tenses, incorrect use of aspect, etc.), e.g. Expected Response: ‘The book was on the table’ − Observed Response: ‘The book is on the table’.

In order to understand the nature of the whole reading process, it is very important to investigate the categories of miscues described above which is the aim of the present study.

Method

Participants

Learners

Eight eleven-year-old learners of English in their second year of study (two Hungarian and two Ukrainian good readers, and two Hungarian and two Ukrainian poor readers) were selected as subjects for this study. Among the good readers there were three boys (two Hungarians and one Ukrainian) and a Ukrainian girl. There were three female poor readers (two Hungarians and one Ukrainian) and a Ukrainian male. The Hungarian learners came from the same school and grade, and had the same English teacher. These were true for the Ukrainian learners. The research was conducted in November, 2000 at two urban schools in Transcarpathia, southern Ukraine. In one of them, the language of instruction was Ukrainian, while in the other one it was Hungarian. These two schools were chosen because they had the best reputation in their region, full of gifted children.

The participants were selected with the help of their teachers. There was a letter written to the two English teachers in which they were told about the purpose of the study and politely asked to help and select the participants for it according to certain criteria. These selection criteria were the following: good and poor readers were needed for the investigation. Based on the literature on fluent reading (both in L1 and FL), for the purposes of the present study I defined a good FL reader as somebody who

- had good phonetic decoding skills, i.e. could pronounce an unknown word on the analogy of familiar words having similar letter clusters (e.g. Vowel + Consonant + Vowel, Consonant + Vowel + Consonant, etc.);

- had sufficient vocabulary and structural knowledge for his/her level, i.e. knew the lexical and grammatical material laid down by the syllabus for his/her level;

- was rapid and precise in his/her word recognition, i.e. the process of recognising a word took no more than two seconds and the word recognised in this way was proper and correct.

Consequently, a poor reader was someone who

- had poor phonetic decoding skills;

- had insufficient vocabulary and structural knowledge;

- was slow and imprecise in his/her word recognition.

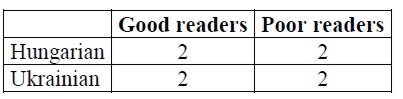

Thus, the research required four types of readers. I decided to have two subjects of each type, eight participants altgether (see Appendix 1). I believed that this number of participants could provide an adequate number of miscues for reliable and valid qualitative analysis.

Teachers

Two English teachers participated in the research, one teaching the Hungarian learner participants and the other the Ukrainian ones. The Hungarian pupils’ teacher was a twenty-four-year-old female with four years of teaching experience, while the teacher of the Ukrainian children was a forty-four-year-old female with 22 years of experience of teaching EFL. The teachers were interested in the topic of the research and were helpful and willing to co-operate.

Research Instruments

Texts

A text that was unknown to the participants was selected as the research instrument. The text had to be short not to frustrate the participants, and authentic, or at least written by a native writer. A text which met the above requirements was selected (see Appendix 2). The learners were planned to be asked to read the text out loud.

The text needed piloting to see if it was appropriate for the research. The piloting procedure was completed by a Hungarian boy aged 11. He was considered a poor reader by his teacher according to the criteria described above. It was considered that if a poor reader was able to read the text aloud, then it would be relevant for the present research. Before reading the text, the boy was given two minutes to get acquainted with the text. The recording was transcribed in order for the data to be retrievable. However, it turned out that the text did not serve its purpose: it was too long (more than ten typed lines), full of unknown words which the child pointed out after the recording (e.g. thousands, fireworks, soldiers), and proper names that caused anxiety in the child and influenced his oral reading performance (e.g. Edinburgh, Tattoo). Therefore it was evident that the first text had to be changed for another one.

Based on the experience of the piloting of Text 1, I created new criteria for selecting the text for this research:

- the text had to be no longer than ten typed lines,

- its vocabulary had to suit and be relevant for the learners' level of knowledge of English,

- it had to contain no proper names.

Taking into consideration these new criteria, Text 2 was selected (see Appendix 3). It was piloted in the same way as Text 1 was, but with another learner. As no difficulties emerged during the piloting of this text, Text 2 was decided to be used for the investigation.

Interview

The aim of the teacher interview was to get deeper insights into the process how the learners acquire English language reading skills, and why teachers apply oral reading in the lessons during which learners evidently make miscues. An interview protocol was designed for conducting the interview with the English teachers of the learner participants. For better understanding between the interviewees and myself, the researcher, I used the respondents' native language (Seliger & Shohamy, 1990), therefore the two interviews were conducted in the mother tongue of the two teachers, i.e. Hungarian and Ukrainian. The interview protocol contained seven questions asking for information about oral reading tasks in the English lessons, e.g. how often such tasks were used in the lessons, why it was important to use oral reading tasks, etc. (see the English version of the interview protocol in Appendix 4).

Procedure

The research was carried out in November, 2000 in Berehovo, Ukraine. Before the recording of the learners’ oral reading, a letter was sent to the two English teachers in which I asked for their help to select the participants for the study. First, the recording of the Ukrainian pupils took place. After two good and two poor readers of English had been singled out according to the criteria enumerated above, the four learners were called in a room familiar to them one by one, but where their teacher was not present. Every child was shown the text to be read. They had the opportunity to look at it for two minutes to familiarise themselves with it, as far as it was a completely unknown text. This preparation time was needed to lessen the stress and anxiety the learners felt when facing an unknown person (the researcher), a tape-recorder and a task the circumstances of which were new to them.

The same procedure was followed a week later with the Hungarian subjects. The oral reading performance of the participants was transcribed phonetically with the help of the symbols of the International Phonetic Alphabet (Kenworthy, 1993). The data obtained that way were qualitatively analysed using Klychnikova’s (1972, 2003) system of classifying reading ‘errors’.

The teacher interviews were conducted after the recordings of the learners, the same day. The place of the interview with the Ukrainian teacher was the same classroom where the Ukrainian learners performed their task; in the case of the Hungarian teacher, it was the staff-room of the school where the she worked.

Results and Discussion

Learners’ Reading Miscues during Oral Reading Performance

In the following section, the learners' reading performances and their miscues will be analysed in respect of the research questions.

During the data analysis phase, the reading miscues were analysed: the observed response (learners’ reading performance) was compared to the expected response, i.e. the word or words on the page (Alderson, 2000).

Based on the classification of Klychnikova (1972), three categories of miscues were singled out: phonetic, lexical and grammatical. Four miscues constituting lexical miscues were found: one made by a good Ukrainian reader (‘dirty’ ‘dry’), another by a poor Ukrainian reader (‘winter’ instead of ‘weather’) and two by the poor Hungarian readers (‘plates’ instead of ‘plants’) (see Appendix 5, List 1). The reason for making these mistakes might be the fact that the learners were not familiar with the words so they pronounced words they knew. Also, the visual images of the expected and the observed responses are similar and this could also influence the learners’ performance.

Two common grammatical mistakes by Ukrainian readers were found (see Appendix 5, List 2). The first was made by one of the good Ukrainian readers: instead of the definite article ‘the’ she pronounced the indefinite article ‘a’. In the second case, one of the poor Ukrainian readers omitted the definite article ‘the’ when reading the sentence ‘Summer is the hottest season’. Two reasons may account for these miscues. Either the article causes a problem to Ukrainian readers because this part of speech does not exist in Ukrainian, or they were due to the readers’ anxiety felt during the recording of the performance. A probable third explanation that clarifies the reason for omitting words when reading aloud might be that when short elements of the text are omitted, it possibly means that the reader was processing the content too quickly for accurate oral reproduction.

Phonetic miscues were found in the biggest number (see Appendix 5, List 3).

They can be subdivided into several subtypes. Intonation miscues belong to type 1 miscues (two examples), Type 2 represents improper word stress (6 examples) and Type 3 miscues are miscues of pronunciation of sounds in words (134 examples).

Type 3 phonetic miscues can be arranged into further subcategories (see Appendix 5, List 3):

- ending -er pronounced as [e] in words like summer, flower, weather by one good and one poor Ukrainian reader, and as Hungarian [ö]* by one good Hungarian reader in the same words;

- diphthongs pronounced as monophthongs in words like daytime, flowers, wear, fly by all the eight subjects;

- wrong monophthong pronounced instead of the proper one in words like honey, summer, and by all the eight subjects;

- short vowel pronounced instead of a long one in words like short, season by the good Ukrainian readers, one poor Ukrainian reader and one poor Hungarian reader;

- long vowel pronounced instead of a diphthong in words like fly, dry by one good Ukrainian reader, two poor Ukrainian readers and two poor Hungarian readers;

- [ð] pronounced as [z] by the four Ukrainian readers and as [d] by the four Hungarian readers in words like the, they;

- adding an extra sound to the word hottest, read as [hostist] by one good Ukrainian reader and one poor Hungarian reader;

- wrong consonant sound pronounced instead of the proper one in words like collect [kolest], bees [di:z], night-time [haitaim], hot [not] by the four Ukrainian readers;

- wrong diphthong pronounced instead of the proper one in the word wear [wie] by one of the good Ukrainian readers;

- words read as written, e.g. season, hottest, summer, short by two poor Ukrainian readers and two poor Hungarian readers;

- diphthongs pronounced instead of monophthongs in words like bees, honey, nectar by two poor Hungarian readers;

- reversal miscue (when the order of sounds of a word is changed), e.g. from read as [form] by one poor Hungarian reader.

There are some very interesting cases among the miscues that have been singled out. In Type 3a, the ending -er of the words flower, weather, summer is read as [e] instead of [ ] by Ukrainian learners most probably because the latter does not exist in Ukrainian. The same ending is pronounced as clear Hungarian [ö], as this sound is the closest and easiest to pronounce for Hungarian learners whose English pronouncing skills have not been totally worked out yet. The influence of the learners’ first language is evident from the mistake types 3b and 3h, when the visual images of Cyrillic letters correspond to letters in the Roman orthography (e.g. English ‘y’ is Ukrainian ‘u’; English ‘c’ is Ukrainian ‘s’, etc.).

] by Ukrainian learners most probably because the latter does not exist in Ukrainian. The same ending is pronounced as clear Hungarian [ö], as this sound is the closest and easiest to pronounce for Hungarian learners whose English pronouncing skills have not been totally worked out yet. The influence of the learners’ first language is evident from the mistake types 3b and 3h, when the visual images of Cyrillic letters correspond to letters in the Roman orthography (e.g. English ‘y’ is Ukrainian ‘u’; English ‘c’ is Ukrainian ‘s’, etc.).

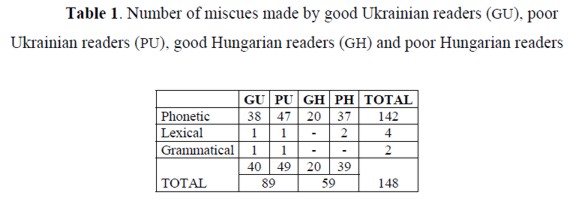

Table 1 shows the number of reading miscues made by learners during the oral reading performance. It is evident that both Ukrainian and Hungarian good readers make less miscues than their peers who were considered to be poor English readers by their teachers. It is also clear from the results that Ukrainian learners made almost twice as many reading miscues as their Hungarian peers. The reason for this can be traced back to the differences in the first language and its impact on the foreign language acquisition process.

Teachers’ Answers to Interview Questions

A few supplementary questions were asked from the English teachers of the Hungarian and the Ukrainian learners to gain insights into the process of reading in the lessons. So, to Question 1 (What method do you use in teaching reading in English to learners?), both teachers answered that they begin teaching reading in Form 5 (learners aged 10) using the method of Starkov and Dixon for this purpose (Starkov, Dixon, & Rybakov, 1990). This is a bottom-up phonic approach to teaching reading which means that first letters and sounds are taught, then words and whole sentences (answer to Question 2: What is the main point of this method?).

To Question 3 (How often do you have oral reading at the English lesson?), both teachers answered that oral reading, i.e. saying a written text aloud, is quite frequent, the Ukrainian teacher said she used this technique in every lesson, while the Hungarian teacher replied that oral reading was used in every second English lesson.

Question 4 inquired about the length of an oral reading task (How long does an oral reading task last?). Teachers replied that it usually ranged from five to ten minutes. The Ukrainian teacher said if there was need (e.g. in case of improper pronunciation of separate words by learners), this kind of activity lasted for fifteen minutes.

When asked about the aim of oral reading in the English lessons (Question 5: What is the aim of oral reading in the lessons of English?), both teachers looked surprised at hearing such a question, as if they thought it was irrelevant to ask them about it. However, they immediately answered (excerpts from the transcripts are given in the author’s translation):

Oral reading in the lessons is good because learners can hear their own pronunciation. If they make a pronunciation mistake, I can immediately correct it. (Teacher of the Hungarian learners)

Reading aloud is very important for practising English pronunciation, stress and intonation. (Teacher of the Ukrainian learners)

Thus, oral reading in the English lessons is mainly applied for practising good pronunciation. This finding was supported by further studies conducted in the field of oral reading and reading miscues (Huszti, 2003, 2007).

The responses to the last two questions (Question 6: Do you give oral reading home assignments to learners? and Question 7: If yes, how often?) given by the two teachers are very similar. The English teacher of the Hungarian participants responded that she did not often give oral reading home assignments, these were quite rare. The English teacher of the Ukrainian participants said that

I seldom give separate oral reading home tasks to my pupils, but I always emphasise that it’s good for their pronunciation if they practise reading a text or anything aloud at home.

From the teachers’ answers it is evident that oral reading plays an important part in the teaching process in these two specific situations. It is used to practise good pronunciation, word and sentence stress and proper intonation. It is quite frequent in the lessons, but home assignments including oral reading tasks are rare.

It is interesting to note that the teachers did not mention comprehension as the aim of reading. Anyway, as the English teacher of the Ukrainian learners pointed out, if her learners did not understand the text they read, they translated the sentences either with the teacher’s help, or using a bilingual dictionary. Both teachers also stated that reading aloud meant a good opportunity for their learners to practise speaking in English. It is obvious that the teachers meant pronouncing words and phrases since speaking a language is not equal to reading it aloud. The teacher of the Ukrainian learners even added that Hungarian learners of English are advantaged in acquiring better pronunciation and intonation compared to Ukrainian or Russian children in Transcarpathia because Hungarian learners are already familiar with the Latin alphabet via their native language, whereas Russian or Ukrainian learners are not. This refers to the evident influence of the learners’ first language on the foreign one.

Conclusions and Implications

Results of teacher interviews confirmed that reading aloud is a common technique used in the English lessons of eleven-year-old Hungarian and Ukrainian learners. The teachers claimed that the main aim of this technique in their lessons is for the pupils to practise proper English pronunciation. However, as the results show, the most frequent miscue type among both the Ukrainian and the Hungarian learners was the phonetic one. This finding completely coincides with what Panova (1989) found among Russian learners. Another result shows that good readers make less miscues than poor readers.

The findings of the research supported the original hypothesis, i.e. they proved that the mother tongue of the learners has some impact on their acquiring reading skills in English as a foreign language. This influence is more significant among Ukrainian native speakers whose first language uses orthography (Cyrillic) different from what the English language uses (Roman). This is not so salient among Hungarian learners whose mother tongue also uses the Roman alphabet.

The most crucial pedagogical implication of the study for English teachers is that they should pay more attention to learners' reading miscues. As the most frequent miscue type was phonetic, teachers should make learners more aware of and emphasize the differences between the norms of the learners' first language and English.

Another implication is for reading research: a comparative analysis of these learners’ reading in Ukrainian and Hungarian as their first language and reading in English as their foreign language through miscue analysis. This research would answer the question whether there is a qualitative and quantitative difference between the miscues in these languages, and what difference there is between the processes of reading in Ukrainian and Hungarian and reading in English in general.

Limitations of the Study

Finally, I am aware of the limitations of my study. First of all, more than eight learners should have been asked to participate in the research to obtain even more reliable and valid data on the processes investigated in the study.

Other aspects of the research methodology had limitations; for example, only one type of text was used to survey the learners’ loud reading and no comprehension measures were applied to check how much the learners understood from what they read. Classroom observations might have provided further supportive explanations for what was going on in the English lessons of the learner participants of this study.

Nevertheless, I believe that the results of this research are of interest to those who research reading in a foreign language.

NOTA AL PIE

* Hungarian [ö] is more rounded and closed than English [ ].

].

References

[1] Alderson, J. C. (2000). Assessing reading. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[2] Bárány, E. (2005). A nyelvek közötti kapcsolat néhány kérdéséról különös tekintettel a magyar − kárpátaljai ukrán (ruszin) nyelvi kölcsösra Kercsa Tamara

(Hol volt hol nem volt) meséskönyve alapján [About the

relationships between the Hungarian and the Transcarpathian Ukrainian (Rusyn)

languages on the bases of Tamara Kercha’s book of tales titled ‘Once upon a time’]. In I. Huszti, & N. Kolyadzhyn (Eds.), Nyelv és oktatás a 21. század elején [Language and education at the beginning of the 21st century] (pp. 10-28). Ungvár: PoliPrint.

(Hol volt hol nem volt) meséskönyve alapján [About the

relationships between the Hungarian and the Transcarpathian Ukrainian (Rusyn)

languages on the bases of Tamara Kercha’s book of tales titled ‘Once upon a time’]. In I. Huszti, & N. Kolyadzhyn (Eds.), Nyelv és oktatás a 21. század elején [Language and education at the beginning of the 21st century] (pp. 10-28). Ungvár: PoliPrint.

[3] Chastain, K. (1988). Developing second language skills: Theory and practice. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

[4] Fordham, P., Holland, D., & Millican, J. (1995). Adult literacy: A handbook for development workers. Oxford: Oxfam/Voluntary Service Overseas.

[5] Gillett, K. (1993). Sun and seasons. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[6] Goodman, K. S., & Burke, C. L. (1973). Appendix for theoretically based studies of patterns of miscues in oral reading performance. Wayne State University, U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare.

[7] Goodman, K. S., & Goodman, Y. M. (1978). Learning about psycholinguistic processes by analyzing oral reading. In L. J. Chapman, & P. Czerniewska (Eds.), Reading: From process to practice (pp. 126-145). London and Henley: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

[8] Grabe, W. (1991). Current developments in second-language reading research. TESOL Quarterly, 3, 375-406.

[9] Hill, D. (1996). Scotland. London: Longman.

[10] Huszti, I. (2003). Why teachers of English in Transcarpathian Hungarian schools apply the oral reading technique in the English lessons. Acta Beregsasiensis, 3, 35-41.

[11] Huszti, I. (2007). The use of learner reading aloud in the English lesson: A look at the micro and macro levels of oral reading. Unpublished PhD dissertation. Budapest: ELTE University.

[12] Kenworthy, J. (1993). Teaching English pronunciation. London: Longman.

[13] Klychnikova, Z. I. (1972, 2003).

(1972, 2003).

[Psychological peculiarities of teaching reading in a foreign language.]

[Psychological peculiarities of teaching reading in a foreign language.]  .

.

[14] Panova, L. S. [Teaching foreign languages at school.]

[Teaching foreign languages at school.]  .

.

[15] Seliger, W., & Shohamy, E. (1990). Second language research methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[16] Starkov, A. P., Dixon, R. R., & Rybakov, M. D. (1990). English textbook for form 5. Teacher’s manual. Kiev - Uzhgorod: Radyanska Shkola.

[17] Stronin, M. F.  (1986).

(1986).

[Is it necessary to teach reading aloud in a foreign language?].

[Is it necessary to teach reading aloud in a foreign language?]. 3, 15-20.

3, 15-20.

[18] Sztanáné Babits, E. (2001). Az olvasási készség fejlesztéséról [About the development of the reading skill]. Új Pedagógiai Szemle, 51(7-8), 180-184.

[19] Urquhart, S., & Weir, C. (1998). Reading in a second language: Process, product and practice. London: Longman.

[20] Vann, R., & Abraham, R. (1990). Strategies of unsuccessful language learners. TESOL Quarterly, 2, 177-198.

[21] Vellutino, F. R., & Scanlon, D. M. (1987). Linguistic coding and reading ability. In D. S. Rosenberg (Ed.), Reading, writing and language learning (vol. 2, pp. 1-69). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[22] Wallace, C. (1992). Reading. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Appendix 1 : Number of learner participants

Appendix 2 : Text 1

The Festival

Every summer thousands of people visit Edinburgh for the Festival. They can listen to music and watch plays and look at pictures. Every day for three weeks, visitors and Edinburgh people can see and do many different things in the mornings, the afternoons and the evenings.

One evening there is a firework display. On that evening there are no cars or buses in Princes Street. Princes Street and the gardens are full of people. They listen to music and watch the fireworks in the sky above the castle.

On other evenings there is the Tattoo. This is in the castle. Soldiers in different countries march inside the castle. There is music from Scottish pipers and other bands. Soldiers, seamen and airmen show their different skills.

At the end of the evening, one piper plays his pipes on the walls of the castle.

(Taken from: Hill, D. (1996). Scotland. London: Longman.)

Appendix 3: Text 2

Summer is the hottest season.

In summer, daytime is long and night-time is short.

In summer, many plants have flowers.

In summer, bees fly from flower to flower. They collect nectar to make honey.

The weather can be hot and dry.

What do you wear in summer?

(Taken from: Gillett, K. (1993). Sun and seasons. Oxford: Oxford University Press.)

Appendix 4 : English Version of the Interview Protocol with Two English Teachers

- What method do you apply for teaching reading in English to your learners? Please explain the essence of this method.

- How often do you have your learners read aloud in the lesson?

In every lesson

In every second lesson

Once a lesson a week

Once a lesson a month

Once in two months

Never

- How long does a reading aloud task last?

- What is the purpose of learners' reading aloud in the lesson?

- Do you give oral reading home assignments to learners? If yes, how often?

Thank you for your answers.

Appendix 5 : Types of miscues

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

Copyright (c) 2009 Matices en Lenguas Extranjeras

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

All content in this journal, unless otherwise noted, is under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Public License