Learning strategies: Tracing the term

Downloads

Estrategias de aprendizaje: Reflexiones sobre el término

Olga Lucía Uribe Enciso* olgalucia35@mail.ustabuca.edu.co

Universidad Santo Tomás

Introduction

Nowadays the term LS (learning strategies) is linked to ‘autonomous’ or ‘independent’ learning. Students who can manage their learning process on their own are able to make decisions in order to address directly what they want or need to learn. Also, LS are considered essential for a successful learning process: if learners know what actions to take in order to deal with learning tasks, they can go through easier and more satisfactory learning experiences (Oxford, 1990).

Therefore, understanding the nature of LS and their implications in the language learning process becomes a relevant issue in our daily practice. In this sense, one of our roles as language teachers is to help students better select and use mechanisms that promote language learning effectively and autonomously, as well as to provide tasks and practices that trigger the implementation of such tools.

To better understand the nature of learning strategies, it is necessary to trace their origins. Therefore, the purpose of this text is to briefly review some of the definitions given to the term ‘Learning Strategies’. This paper tries to follow a chronological thread towards which cognitive and pedagogical concepts of LS e.g. LS conscious or unconscious nature, LS differences or similarities to CS (Communication Strategies), and LS classifications derived from such conceptions, are drawn together.

First attempts

Corder (1967) claimed that second or foreign language learners errors are evidence of their efforts to organize and coordinate input, which in turn means that learners underlying linguistic competence is in development. During such natural progression, there is an emerging linguistic system that is neither the L1 (first language) nor the TL (target language) pure systems, but a continuum moving away from the L1 towards the TL. Some years later, Selinker (1972) called it ‘interlanguage’.

Selinker (1972) proposed that ‘interlanguage’ is the result of five crucial cognitive processes present in the acquisition of a second language: ‘language transfer’, ‘transfer of training’, ‘strategies of learning a second language’, ‘strategies of communication in second language’, and ‘overgeneralization of language material’. Consequently, learners’ errors are seen as positive indicators of learners’ going through these processes in order to manage the TL and LS as the specific approaches learners use to understand the input and control the output. Therefore, LS are responsible for ‘interlanguage’ development and systematicity.

This standpoint of language learning shows learners as being capable of making conscious efforts to regulate their learning process in order to manage the L2. Besides, the studies carried out by Rubin (1975), Stern (1975), Wong-Fillmore (1976), McLaughing (1978), Bialystok (1978), and Dansereau (1978), among others, on cognitive processes of language learning promoted the research to find out what learners do to encourage and control their language learning process.

In 1971, Rubin started doing research to discover what successful language learners do in order to make the data available for less successful language learners. Later Rubin, (1975)1 based on those behaviors and situations identified (through learners’ reports or observations) as contributory to language learning, defined strategies as ‘the techniques or devices which a learner may use to acquire knowledge’ (1975:43) and classifies strategies in terms of processes that influence language learning in both direct and indirect ways.

Stern (1975) also introduced the idea that the ‘good language learner’ does something special or different that leads him to be successful at his language learning process. He proposed a list of ten language learning strategies that, according to him, are characteristic of successful language learners. He also accounts for learning strategies as higher order actions to approach learning with that influence the selection of more specific problem-solving techniques.

Later, Naiman et al. (1978), also based on personality and cognitive features of language learners, used Sterns strategies and interviews with successful language learners, and proposed five major strategies which account for language learning effective experiences.

These strategies entail factors related to the importance of the learning environment in learners’ active involvement in their language learning process, the awareness of the L2 as a linguistic system and tool for communication and interaction and the efforts its learning requires.

Wong-Fillmores research (1976) on five Mexican children paired off with five American children, showed that the use of social strategies mainly but also cognitive strategies results in improved communicative competence. Children did not need a wide range of expressions to be able to interact but social strategies instead such as asking questions or cooperating with peers, cognitive strategies like practicing in natural spontaneous situations and recognizing common expressions, plus a few well-chosen formulas which helped them improve their communicative competence in L2. Even though he does not propose a classification or list of LS, his study shows that those learners took actions to learn to communicate in a new language.

McLaughing (1978) stated that second language learners, in formal instruction settings, seem to experience two different processes called ‘acquisitional heuristics’ (strategies) and ‘operating procedures’ (tactics). The former are superordinate, abstract, constant long-term processes (Stern 1987:23) common to all language learning (L1, L2, L3) and could be based on innate cognitive mechanisms related specifically to language, which lead to the development of natural language sequences. The latter are ‘short-term processes used by the learners to overcome temporary and immediate obstacles to the long-range goal of language acquisition’ (Stern 1987:23); they emerge under classroom conditions where language is presented in an order that deviates from the natural order of acquisition, which hinders learners from using their natural mechanisms and therefore, they have to resort to different problem-solving tools which he called operating procedures’.

Another study was developed by Bialystok (1978) whose ‘second language learning model’ assumes that language is processed by our minds as any other type of information, and distinguishes between processes (essential actions) and strategies (voluntary mental actions). She proposes that strategies are “optimal methods for exploiting available information to increase the proficiency of L2 learning (…) They operate by bringing relevant knowledge to the language task that have the effect of improving performance” (1978:76). Therefore, learners choose LS according to the following criteria: their proficiency level, the knowledge needed to develop the task, the complexity of the task, and learners individual differences.

In addition, learners choice of learning strategies enables them to better access the three sources of knowledge they use when interacting: ‘other knowledge’, ‘explicit or conscious knowledge’, and ‘implicit or intuitive knowledge’(Vinja 2008:33). The first deals with what the learner brings to the language task (e.g. background knowledge); the second refers to conscious facts about the language (e.g. systemic knowledge); and the third concerns the language individuals already know and use effectively as a result of exposure and experience (e.g. formulaic language). Therefore, learners choose between ‘formal strategies’ (dealing with conscious learning of accurate linguistic forms) and ‘functional strategies’ (related to language use) according to the type of knowledge they need to focus on when carrying out the language learning task.

Dansereau (1978, 1985) applied the findings of cognitive psychology to formal instruction and defines learning strategies as “a set of processes or steps that facilitate the acquisition, storage and/or utilization of information” (Segal, Chipman & Glaser 1985:210). He divided learning strategies into ‘primary strategies’ and ‘support strategies’ and attributed to them the following characteristics: First, they may improve the level of the learners’ cognitive functioning by means of a direct or indirect impact on learning materials. Thus, primary strategies act to better handle the materials and supporting strategies to improve internal psychological conditions (In-Sook, 2002) and the learning environment so that primary strategies are implemented effectively. Second, they can remain fixed (algorithmic) or can be modified (heuristic) according to the task requirements, scope and complexity, and the learners’ individual differences (Segal, Chipman & Glaser, 1985).

Rigney (1978:165) defined learning strategies as “steps taken by the learner to aid the acquisition, storage, and retrieval of information”. This view highlights the cognitive side of strategies as operations and procedures that make information processing more effective and whose selection depends on task requirements. Two types of learning strategies are proposed: ‘system-assigned’ and ‘student-assigned’. The former involves the strategies externally provided by the learning material itself so that learners are guided to use the appropriate learning strategies to deal with the instructional material. The latter refers to the strategies used by learners as a result of their own choice.

Also, Rigney (1978) distinguished between ‘detached’ and ‘embedded’ LS which coexist with ‘system-assigned’ and ‘student-assigned’ LS. ‘Detached’ strategies are those “presented independently of the subject matter” (Gram 1987:13) so they are general and applicable to different learning activities. On the other hand, ‘embedded’ strategies are intrinsically related to the learning task and therefore, they are required to accomplish the task.

Nambiar (2009) reported important studies on LS. For instance, Wesche (1975) studied adult language learners in the Canadian civil service and concluded that good language learners find their own way and choose their actions according to the task to be solved, and that successful language learners display more and more varied behaviors than poor learners do, results that support Sterns (1975) and Rubin & Thompson’s (1983) findings. Another example is the study by Weinstein (1978) on ninth graders which shows that the implementation of a general learning strategies program helped learners to increase acquisition, retention, and retrieval of material by using different procedures (Nambiar 2009:133) .

These last two studies cited above support the notion of learning strategies as actions, behaviors or steps that can be taught to learners in order to help them better their language learning process by consciously choosing and employing strategies to solve different tasks and situations.

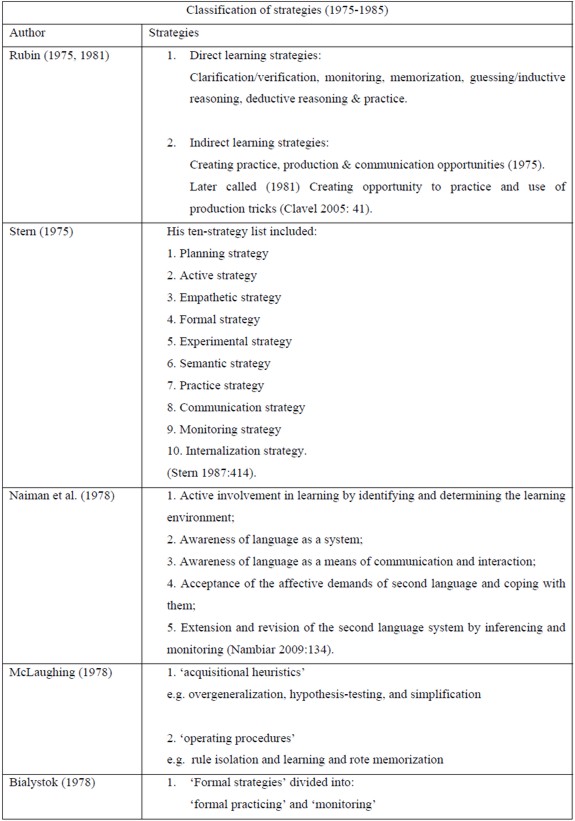

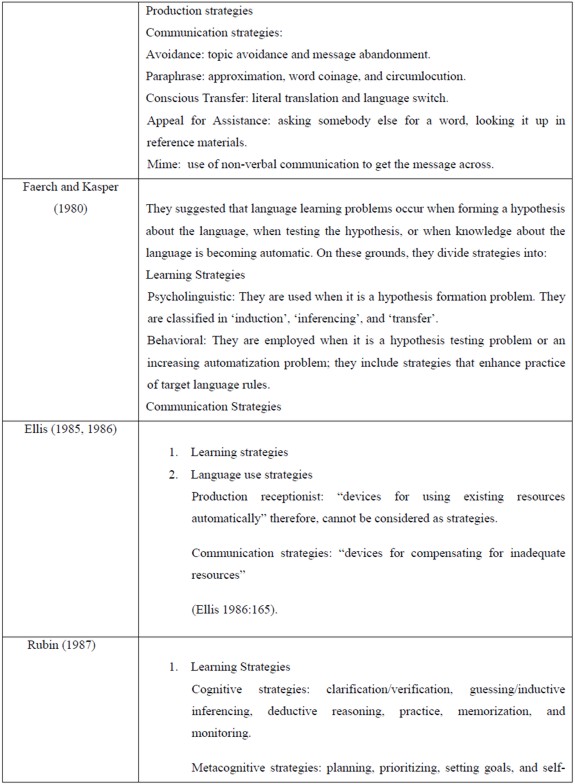

Table 1. Classification of learning strategies (1975-1985)

The classifications above (Table 1) have in common linguistic aspects such as ‘semantic strategy’, ‘awareness of language as a system’, or ‘learn chunks of language as whole formalized routines to help them perform beyond their competence’, which deal with learning the formal component of the language.

Besides, those classifications share cognitive and metacognitive actions which have to do directly or indirectly with using and practicing the L2 such as ‘formal practicing of the language’, ‘inferencing’, ‘letting the context help them in comprehension’ and ‘creating practice opportunities’, ‘planning strategy’, ‘concentration strategies’, respectively.

In addition, social factors related to using the language as a tool to build relationships and do transactions such as ‘awareness of language as a means of communication and interaction’ and ‘production tricks’ are common to those classifications, as well as affective aspects which deal with attitudes and feelings towards the language learning process such as ‘empathetic strategy’, ‘acceptance of the affective demands of second language and coping with them’, or ‘learning to live with uncertainty’.

All of the above aspects are implicit in language learning and, if well-addressed whether in natural or instructional settings, result in successful language learning experiences, which is the primary purpose of impLearner-centered communicative approaches in LS term development.

After the previous attempts to define and classify learning strategies, the emergence of learner -centered communicative approaches which focus on developing communicative competence encourage learners to be active participants of their language learning process and give great significance to learning strategies.

Canale and Swain (1980) and Canale (1983) propose a theoretical framework of CC (Communicative Competence) which includes ‘grammatical competence’ (mastery of linguistic components), ‘discourse competence’ (use of devices to make texts cohesive and coherent), ‘sociolinguistic competence’ (appropriate language use according to the context of the communicative situation), and ‘strategic competence’, which is, for the first time, formally postulated as a component of CC so that stronger interest in knowing how learning strategies operated to favor the development of CC was generated.

‘Strategic competence’ has to do with the learner’s ability to use strategies to compensate for lack of grammatical, sociolinguistic or discourse competences so that communication is promoted. Thus, this proposal strengthens the idea that certain language learning behavior needs to be necessarily strategic in order to make communication effective by overcoming difficulties and obstacles due to lack of proficiency in any area of communicative competence. Thus, verbal and non-verbal actions such as paraphrasing, using mime or gesture, or slowing speech come into play to repair interaction breakdowns.

Wenden (1981), within the frame of training learners to self-directed learning, referred to learning strategies as both “pedagogical tasks (my term) learners perform in response to a learning or communication need” (1981:4) and “characteristics of learners’ overall approach to language learning” (1981:4). As pedagogical tasks, strategies are seen as focused tasks that can be observable or unobservable; as learner features, strategies are seen as the attitudes and behaviors learners adopt towards their learning process, for example, passive or active learners, shy or risk-taker learners. Such views of LS are focused on helping learners enhance their learning processes as well as facilitating communication.

Later, Wenden (1991, 1998) stated that learning strategies are “… mental steps or operations that learners use to learn a new language and to regulate their efforts to do so” (1998:18). Richards and Schmidt (2002) take the same path when they define learning strategies as the different ways in which learners try to understand the grammar, meanings and uses, and other aspects of the language they are learning. These two definitions approach learning strategies as actions taken by learners to facilitate their language learning process.

Another important aspect in the development of the term LS is the contribution made as a result of studies on cognitive psychology (Atkinson & Shiffrin 1968, 1971; Gagne 1977; Lachman et al. 1979; Anderson 1980, 1983), which supports language learning from an information processing point of view. Even though such studies provide LS with a theoretical background, researchers continue to emphasize the role of LS as tools to make L2 learning and communication easier and more effective.

For example, OMalley et al. (1985) stated that LS are actions or behaviors learners do to better handle learning activities. He proposed a division of LS in: ‘Metacognitive strategies’ which help learners regulate their learning process and later, to self-evaluate their results of their learning activity (Brown et al. 1983); ‘Cognitive strategies’ which deal directly with manipulating information so that learning is promoted. They organize and process information about the L2 in the short-term and the long-term memory); and, ‘Socio-affective strategies’ which interact with others and control emotions and strive to aid learning (O’Malley and Chamot 1990).

Weinstein and Mayer (1986), in their book The teaching of learning strategies described LS as “…behaviors or thoughts that a learner engages in during learning that are intended to influence the learners’ encoding process” (1986:315) and that are used to facilitate learning. Later, Mayer (1988) described LS as “behaviors of a learner that are intended to influence how the learner processes information (p.11) in order to better manage it. Both definitions account for LS as ways to improve learning by processing information more effectively.

Oxford (1985) and Oxford and Crookall (1989:404) stated that LS, regardless of how they are named (techniques, steps, behaviors, or actions) are to ease the learning process and make it more efficient and effective since they help learners learn to learn, solve problems and develop study skills. Later, Oxford (1990:8)2 defines LS as specific actions learners take to facilitate and accelerate the learning process by making it more enjoyable, self-directed, and effective as well as possible to be transferred to different situations.

Both definitions account for learning strategies as tools that promote learning process whether academic or not, and consider the learning process as a permanent, dynamic and flexible one. After that, based on Rigney (1975) and her own work in 1990, Oxford characterizes LS as

“…operations employed by the learner to aid the acquisition, storage, retrieval and use of information; specific actions taken by the learner to make learning easier, faster, more enjoyable, more self-directed, more efficient, and more transferable to new situations.” (2001:166)

Such definition involves both the cognitive and pedagogical views of LS whose ultimate purpose is getting learners to aid not only their L2 learning process but also any other type of learning by effectively processing information and tackling learning situations and experiences.

Similarly, O’Malley and Chamot (1990) consider LS as actions to deal with effective information processing process. They affirm in the introduction of their book ‘Learning Strategies in Second Language Acquisition’ that LS are

”the special thoughts or behaviors that individuals use to help them comprehend, learn, or retain new information. … Learning strategies are special ways of processing information that enhance comprehension, learning, or retention of the information.” (1990:1)

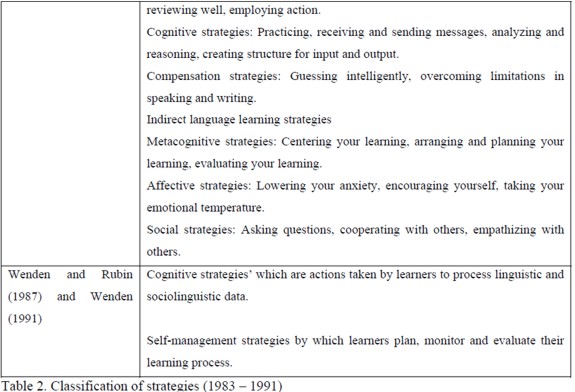

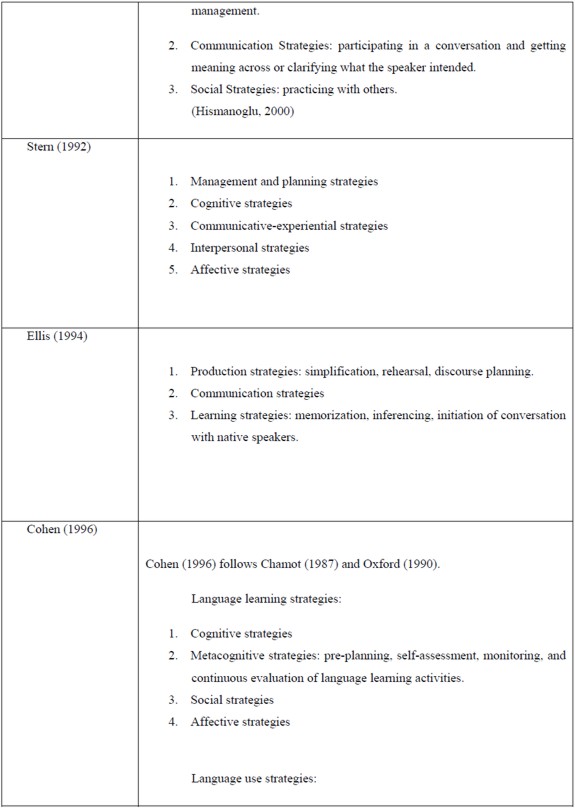

The table below shows the classifications of LS between 1983 and 1991 proposed by some of the researchers already mentioned.

As a whole the above definitions of LS3 are related to behaviors, actions, operations, moves, techniques, steps, thoughts, or measures, which learners apply in order to ease, assist, guide, promote and overcome limitations and problems in their language learning process. Although there are variations in LS scope, whether seen from a cognitive, a pedagogical approach or both, all of them account for LS as tools to help learners aid learning.

For instance, from the cognitive viewpoint where LS are aimed at enhancing the information processing process, we have Weinstein & Mayer (1986), Mayer (1998), OMalley (1985) OMalley and Chamot (1990); LS as steps to promote learning as a process that must be transferable to new tasks and contexts, (Oxford and Crookall, 1999) and Oxford (1990, 2001); LS as specific actions to enhance the language learning process, (Wenden, 1995, 1998) and Richards & Smith (2002); and lastly, LS as pedagogical and cognitive features and actions to promote learning (Wenden, 1981).

Conscious vs Unconscious nature of LS

Apart from trying to reach agreement on what learning strategies are, another debatable question regarding the cognitive aspect of learning strategies arises: how do learning strategies operate? Are they conscious or unconscious actions or behavior? Do individuals need to be aware of their use of learning strategies to consider them as strategic actions? Let us review what some researchers have suggested regarding this issue.

In Anderson’s cognitive theory framework (1983), strategies are seen as complex skills, that is to say, “as a set of productions that are compiled and fine-tuned until they become procedural knowledge” (1990:43). When explaining procedural knowledge (knowing how to do something), he claims that we lose our ability to describe verbally the rules that initially allow the strategy due to their recurring use in a procedure. Thus, learning strategies are considered unconscious actions since they have become automatic.

Conversely, Weinstein and Mayer (1986) stated that LS exist to facilitate learning so therefore they are not incidental (unconscious) but intentional (conscious) when employed by the learner. They assert that the purpose of using strategies is to “affect the learner’s motivational or affective state, or the way in which the learner selects, acquires, organizes, or integrates new knowledge” (1990:43). Therefore, learning strategies should be consciously chosen and used.

Along the same line, OMalley and Chamot (1990) argued that learning takes place whether using conscious or unconscious strategies or not, and pointed out that for mental processes to be strategic they must be done consciously.

Individuals may learn new information without consciously applying strategies or by applying inappropriate strategies that result in ineffective learning or incomplete long-term retention. Strategies that more actively engage the persons mental processes should be more effective in supporting learning. These strategies may become automatic after repeated use or after a skill has been fully acquired, although mental processes that are deployed without conscious awareness may no longer be considered strategic.”(p.18)

Besides, leaning on Andersons cognitive theory, OMalley and Chamot (1990) explained that LS are represented as procedural knowledge and therefore they are performed unconsciously. However, in early stages LS are used consciously until they become automatic or proceduralized so that the individual is not aware of them. Consequently, LS are not strategic anymore since they are not consciously selected from a range of actions to better tackle a task. In terms of Rigney (1978) LS become embedded in definite tasks which are successfully carried out when done by using the strategies intrinsically linked to them.

To support this view, they cite Rabinowitz and Chi (1987), who suggested that strategies need to be conscious actions or behaviors in order to be considered ‘strategic’ (O’Malley and Chamot 1990:52). Later, Chamot (2005) suggested that, even though learning strategies become automatic through repeated use and therefore are not strategic, learners should be capable of bringing them back to conscious awareness if they were told to report them. Such a view sees LS as both: conscious behaviors if they can be accounted for and unconscious ones when done automatically or proceduralized.

Similarly, Oxford (1990), leaning on the ancient Greek definition of ‘strategy’, argued that it implies consciousness and intentionality. Also, she states that learners make conscious efforts to manage their learning and these are reflected in the learning strategies used. Also, Oxford and Cohen (1992:12) reiterated that LLS are conscious behaviors aimed at improving language learning. Otherwise, strategy training is purposeless. Learners need to be aware of the strategic actions and behaviors they will undertake in specific situations.

Besides, Ellis (1994) asserted that if the learner is not conscious of using the LS since they have become proceduralized as a result of being used repetitively, he cannot account for them verbally. Thus, when strategies cannot be described by means of verbal report, LS lose their importance as strategies since their purpose is to ease learning (Cohen 1996); when LS are not chosen intentionally but automatically, learning has taken place. Now the individual already knows how to do something (Anderson 1983).

In addition, Cohen (1996), drawing on Schmidt (1994), suggested that learning strategies are within both the learners focal and peripheral attention since they can account for their actions and thoughts, if they are asked. He claims that the learner’s behavior is a strategy if he can explain why the behavior took place; otherwise, it is a process. Later, he stated that learning strategies are “the steps or actions selected consciously by learners either to improve the learning of a second language or the use of it or both” (1998:5). Also, Hsao and Oxford (2002) affirmed that as LS are employed to manage the language learning process, accomplish objectives and become autonomous, awareness or conscious intention in their use is required.

A different point is made by Carver (1984) who used the term learner strategies’ to refer to a part of a learning methodology whose embracing category is ‘learning styles’. Learning styles originate certain types of ‘work habits’ which involve ‘plans’. These plans are carried out by ‘learner strategies’ that are defined as ‘conscious or unconscious behaviors’ (1984:125) that emerge from work habits. The conscious use of learner strategies contribute to the development of autonomy and therefore, to self-directed learning. However, strategies do not have to be necessarily conscious to be strategic behaviors. Besides, Selinker et al. (2000:31) also defined LS as unconscious or conscious cognitive activities that implied second language information processing in order to express and convey meaning.

It would appear, then, that the moot point about consciousness or unconsciousness of LS is, among other things, related to their possibility of being verbally reported, intentionally selected, and explicitly taught to learners. However, I think that learning strategies can be both unconscious and conscious at the same time. It means that individuals can use internalized and proceduralized actions (unconscious) and be able to account for them when required (make them conscious). I follow Carver (1984) and Selinker (2000) since I consider LS as actions you do or tools you use, whether conscious or unconscious, in order to perform tasks effectively, solve problems efficiently and become autonomous learners.

Notwithstanding, when a learner consciously or unconsciously resorts to ‘use of synonyms’ or ‘circumlocution’, because he does not know the exact word, can we say he is using a learning strategy since he is exploring his L2 knowledge and making connections among its elements, or a communication strategy, since he wants to avoid communication breakdowns and convey the intended meaning. Are LS different from CS or do LS embrace CS?

How Similar or Different are Learning Strategies and Communication Strategies?

Unfortunately, there is no common agreement on whether they all refer to the same strategies under different names or are they somehow different. Concerning this topic, Selinker (1972) separated ‘strategies of learning a second language’ from ‘strategies of communication in second language’. The first are cognitive and involve handling language learning material, whereas the second deal with using language for communication purposes. ‘Strategies of communication’ might be responsible for fossilization since they assist learners in communicating in a simple way which might make them feel that they do not need to go further in their language learning process.

Brown (1980) distinguished LS from CS based on the argument that learning deals with the input and intake part of the process and communication with the output or production the learner is able to perform when communicating. He claimed that there are CS which do not result in learning necessarily such as ‘topic avoidance’ or ‘message abandonment’. However, he later admitted (Brown, 1994) that it is sometimes difficult to differentiate between LS and CS.

Faerch and Kasper (1980) accounted for learning strategies on psycholinguistics bases and the criteria of ‘problem-orientedness’ and ‘consciousness’. The former entails experiencing a problem to achieve a specific learning objective which has to do with figuring out, understanding and mastering the rules of the language; the latter deals with learners recognition of the problem. Thus, they define LS as “potentially conscious plans for solving what to an individual presents itself as a problem in reaching a particular learning goal” (1980: 60).

On the other hand, they proposed that CS are “potentially conscious plans for solving what to an individual presents itself as a problem in reaching a particular communicative goal” (Faerch and Kasper 1980:36). They asserted that these strategies are used when learners find difficulties in communicating in the target language due to their limited interlanguage (problem-orientedness) and become aware of such problems (consciousness).

Even though Faerch and Kasper (1980) separated LS (used to deal with learning problems) and CS (implemented to tackle communication problems), they asserted that CS promote learning when involved in hypothesis formation and automatization, and only if they are triggered by accomplishment instead of avoidance behavior.

Rubin (1981), in her taxonomy of LS, included CS as part of ‘production tricks’, which are processes that contribute indirectly to learning such as using circumlocutions, synonyms or cognates, formulaic interaction, and contextualization to clarify meaning. Some years later, Rubin (1987) proposed a LS taxonomy which separates CS from LS on the grounds that CS are directly related to negotiating and conveying meaning so that the speaker expresses what he really intends to.

In addition, Tarone (1980, 1981 cited in OMalley & Chamot, 1990) proposed a division of strategies: LS which are “attempts to develop linguistic and sociolinguistic competence in the target language” (p.43), which narrows the focus to L2 mastery and ‘language use strategies’. The second ones are subdivided into ‘production strategies’ which deal with using language knowledge successfully and effortlessly so that communicative goals are achieved and CS which promote negotiation of meaning since they compensate for the incapacity to attain a language production goal. Also, she suggested that CS can promote language expansion since they help students express what they really want or need to say. Whether or not the learners output is correct regarding grammar, lexis, phonology or discourse, she or he will be inevitably exposed to language input while using the language in order to communicate which may cause learning to take place; in this way, the strategies involved in the process are LS.

Thus, the crucial point is the fact that it is a LS when there is motivation to learn the language rather than motivation to communicate which triggers the use of the strategy. However, Tarone (1981, 1983) accepted that it is problematic to know whether it is the desire to learn or to communicate which motivates the learner to use a strategy. Also, two things could be possible: first, that learners experience both motivation to learn and to communicate simultaneously; second, that the desire to communicate brings about learning incidentally.

Ellis (1986:165) proposed that LS are different from ‘language use strategies’ since the former are used to acquire or learn the target language, and the latter are employed to use resources automatically (production receptionist) and compensate for lack of knowledge or inappropriate resources (CS). He also claimed that learning prevention may take place when CS achieve the communicative goal successfully since “skillful compensation for lack of linguistic knowledge may obviate the need of learning” (Griffiths 2004:3). However, Ellis (1994) admitted that it is extremely difficult to know whether a strategy is used because of a desire to communicate or learn.

Stern’s (1992) defined strategies as “broadly conceived intentional directions” (Griffiths 2004:3) and proposed a taxonomy of LS that includes ‘communication-experiential strategies’ as one of its categories. These strategies are used by learners to keep the flow of the conversation. Consequently, CS are not different from LS but in only one of their components, which sees communication in L2 as a tool to enhance language learning.

Cohen (1996) proposed that ‘language learner strategies’ are actions chosen by learners in order to improve and/or use the language; they comprise ‘second language learning’ and ‘second language use’ strategies. The former have “an explicit goal of helping learners to improve their knowledge and understanding of a target language” (1996:3); they are conscious actions taken by students in order to facilitate and personalize their language learning process. The latter concentrates on using what the learners actually have in their current interlanguage.

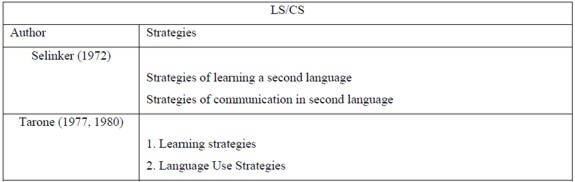

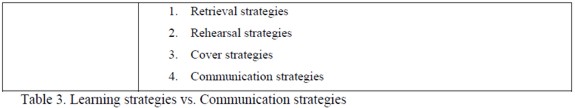

The following table shows how some researchers place CS in relation to LS.

Based on the previous account of LS and CS, I think I might follow Tarone (1983), Selinker (1972), and Ellis (1986) when they affirm that boundaries between LS and CS become blurred since their use can be triggered by both: the desire and need to communicate and the desire and need to learn. Also, Faerch and Kasper’s position (1980) on the role of CS -not only in compensating for insufficient language proficiency but also in promoting learning as long as they are used to fulfill the communicative purpose intended- supports the interactional and transactional view of language which learner-centered communicative approaches require.

To illustrate my point, I will use a common situation in formal instruction. When learners develop tasks aimed at improving accuracy, it is assumed that LS play a significant role since learners have to pay attention to the formal aspects of the language (grammar, lexis, phonology, and discourse items) in order to manage them correctly and appropriately in the given situation. On the other hand, when learners carry out fluency activities where the intended focus is communication and negotiation of meaning, it is expected that CS are naturally triggered. However, it is clear from the teaching point of view since teachers consciously know the type of strategies they expect learners to use when doing accuracy or fluency activities, but it is uncertain from the learning side as we do not know for sure what strategies learners actually implement or what motivates their use, if their desire is to learn or to communicate.

A well-known LS taxonomy

Finally, let us move towards Oxfords (1990) taxonomy of learning strategies which is well-known around the world. Ellis (1994:539) affirmed that it is perhaps the most comprehensive classification of learning strategies to date (Codina, 1998). Also, Jones (1998) stated that Oxfords system is more detailed and inclusive than previous categorization models since it tries to gather much of what has been proposed about LS.

Conversely, Codina (1998) claimed that Oxfords system does not provide good theoretical reference since it does not account for overlapping between categories or the placement of certain strategies under certain categories; for instances, she criticized Oxfords not separating LS from CS: For example, Oxford (1990:19) includes switching to the mother tongue as a learning strategy! (1998:91). However, she admitted that Oxford’s taxonomy offers a range of useful activities.

Oxford (1990) classified strategies into two main groups: Direct strategies which "involve direct learning and use of the subject matter" (1990:12) and “require mental processing of the language” (1990:37), and “Indirect strategies’ which “support and manage language learning without (in many instances) directly involving the target language” (1990:135). ‘Direct strategies’ are divided into three groups: ‘Memory strategies’ which aid information storage and retrieval; Cognitive strategies which promote new language understanding and production through different means; and ‘Compensation strategies’ whose role is to “allow learners to use language despite their often large gaps in knowledge” (1990:37). ‘Indirect strategies’ are also divided into three groups: ‘Metacognitive strategies’ which help learners manage and regulate their own language learning process; ‘Affective strategies’ which enable learners to control affective factors such as emotions, attitudes, motivations, and values involved in their language learning process; and ‘Social strategies’ which encourage and help learners to communicate (1990). Each of these groups is subdivided into strategies containing more detailed strategies. However, she admits and points out that some categories overlap:

“For instance, the metacognitive category helps students to regulate their own cognition by assessing how they are learning and by planning for future language tasks, but metacognitive self-assessment and planning often require reasoning, which is itself a cognitive strategy! Likewise the compensation strategy of guessing, clearly used to make up for missing knowledge, also requires reasoning (which explains why some specialists call guessing a cognitive strategy), as well as involving sociocultural sensitivity typically gained through social strategies.”(1990:16)

We can see that her taxonomy emerged from her own and other researchers previous studies and attempts to classify learning strategies. For instance, if we look at Tarone’s taxonomy (1977, 1980) in Table 3, we notice that even though they are under the term ‘communication strategies”, they correspond exactly to Oxford’s (1990) taxonomy of learning strategies but under different names: “compensation strategies / overcoming limitations in speaking and writing’: ‘avoiding communication partially or totally’, ‘adjusting or approximating the message’, ‘coining words’, ‘using circumlocution or synonym’, ‘switching to the mother tongue’, ‘getting help’, and ‘using mime or gesture’. Also, ‘translating’ which is a subdivision of ‘cognitive strategies / analyzing and reasoning’.

Besides, if we compare Rubin (1987) with Oxford (1990), we find that Rubin’s cognitive strategies embrace Oxfords memory, cognitive and metacognitive strategies and that Rubin’s communication strategies match Oxford’s compensation strategies, and social strategies are included in both. However, Rubin’s taxonomy does not account for affective strategies as Oxford’s does.

Also, we can see that Selinker’s (1972) ‘strategies of learning a second language’ correspond to Oxford’s memory, cognitive and social strategies, and Selinker’s ‘strategies of communication in a second language’ are related to Oxford’s compensation and social strategies. Affective and metacognitive strategies are missing in Selinker’s proposal.

If compared with O’Malley & Chamot’s (1990) classification that appeared in the same year, we notice that O’Malley & Chamots and Stern’s (1992) cognitive strategies embrace Oxfords cognitive, memory and compensation strategies; O’Malley & Chamot’s socio-affective strategies present in Stern’s (1992) taxonomy as affective strategies and interpersonal strategies- correspond to Oxford’s affective and social strategies. Metacognitive strategies are present in both as well as in Stern’s (1992) classification, where they are called management and planning strategies.

One important outcome of Oxfords (1990) taxonomy is the SILL (Strategy Inventory of Language Learning) since it is a very helpful instrument to test the use of strategies in ESL/EFL learners. This tool along with the range of strategies available in the taxonomy is useful to identify what actions learners actually take to deal with their language learning development (Hsiao and Oxford 2002). Thus, the taxonomy and the inventory not only help trainers but also learners in their process of becoming autonomous language learners. Besides, researchers have found these instruments effective to develop studies that contribute to enriching the use of learning strategies such as variables affecting their choice or their teachability.

Oxford (1990) stated that learning strategies could be used in any academic field. However, her taxonomy focuses on language learning since it is her work field. Also, it is valuable to highlight what she affirmed about learning strategies: “A given strategy is neither good nor bad; it is essentially neutral until the context of its use is thoroughly considered.” (Oxford 2003:8). It means we cannot regard strategies as useful or useless but as more or less appropriate to learners’ characteristics, tasks requirements and learning circumstances.

Conclusions

1.Since their origins LS have been seen as actions learners take to tackle learning situations effectively regardless of their possibility of being consciously or unconsciously chosen or verbally reported.

2. LS play a crucial role in learner-centered communicative approaches as they enable learners to be active and autonomous since learners can use LS to facilitate their learning process.

3. From both pedagogical and cognitive viewpoints, LS go beyond the formal academic setting as they help individuals to deal with different learning situations and give them the opportunity to experiment with which strategies are more suitable to the task and their own needs.

4. Tarone (1983), Brown (1980), and Ellis (1986) share the idea that it is not feasible to discriminate between LS and CS since it is difficult to know the real intention for using a strategy; the strategy choice might be motivated simultaneously by both learning and communication.

5. Conversely to Tarone (1983), Stern (1992), and Cohen’s views (1996) that even when the intention is to communicate, learning often occurs because of the exposure and interaction in the L2. Selinker (1972) and Ellis (1986) stated that CS or ‘language use strategies’, respectively, prevent language learning and therefore may result in fossilization. They argue that when learners use such strategies to compensate for their lack of competence, they manage to communicate regardless of their insufficient knowledge, which makes learners feel they do not need to improve their language level. However, there are a number of factors that account for fossilization such as motivation, exposure to the L2, lack of practice, gaps in linguistic knowledge, etc. (Selinker 1973,1993; Han 2004) to which not only CS but also LS (inappropriate choice or lack of use) might be added.

6.Even though Oxfords learning strategies taxonomy has been criticized, it has been widely used around the world in numerous studies. Her classification presents detailed categories and subdivisions that help to identify the strategies used by learners, which makes her taxonomy a useful tool not only for teachers to guide students better but also for students to be independent and effective learners.

After having gone through a variety of studies trying to account for a definition of learning strategies, their unconscious or conscious nature, their closeness to communication strategies and different classification proposals, what I really want to garner attention to is their use as learning promoters and facilitators which are the common findings among the researchers and authors cited. I intended to trace the term just to broaden knowledge and interest in the topic.

NOTAS AL PIE

Este artículo se recibió en junio 24, 2010 y fue aceptado para publicación en octubre 22, 2010.

* holds a Bachelors degree in Languages from Universidad Industrial de Santander, a specialization in Mother Tongue Pedagogy and Semiotics, a Master’s degree in TEFL from the University of Jaén-Funiber, a Master’s degree in Teachers Training in Spanish as a Foreign Language from the University of Jaén-Funiber. She is currently working as a full-time professor at Universidad Santo Tomás, Bucaramanga campus and she is the coordinator of the Foreign Langauges and Cultures Institute at the same university.

1 Oxford (1994) emphasizes the features of good language learners stated by Rubin (1975) since she sees them as real learning strategies:

“are willing and accurate guessers; have a strong drive to communicate; are often uninhibited; are willing to make mistakes; focus on form by looking for patterns and analyzing; take advantage of all practice opportunities; monitor their speech as well as that of others; and pay attention to meaning.”(p.1)

2 Oxford (1990:9) states that learning strategies have the following features:

1.“Contribute to the main goal which is communicative competence. 2. Allow learners to become more self-directed. 3. Expand the role of new teachers. 4. Are problem-oriented. 5. Involve many aspects of the learner, not just the cognitive. 6. Support learning both directly and indirectly. 7. Are not always observable. 8. Are often conscious. 9. Can be taught. 10. Are flexible. 11. Are influenced by a variety of factors such as: degree of awareness, task requirements, teacher expectations, age, sex, nationality/ethnicity, general learning style, personality traits, motivation level, and purpose for learning the language. 12. Involve more than just cognition.”

3 “Larsen-Freeman and Longs (1991) landmark book on second language acquisition research reflects the confusion by appearing to equate learning strategies with all of the following: learning behaviors, cognitive processes, and tactics (p. 199). Wenden (1987, 1991) notes that these terms are all used synonymously: learning strategies, techniques, potentially conscious plans, consciously employed operations, learning skills, cognitive abilities, processing skills, problem-solving procedures and basic skills. Oxford (1990b) adds that learning strategies are also equated with thinking skills, thinking frames, reasoning skills, tactics and learning-to-learn skills.”

(1992:6)

References

[1] Brown, D. (1980). Principles of Language Learning And Teaching. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

[2] Brown, H. Douglas (1994). Principles of Language Learning and Teaching. Prentice. Hall: New Jersey 3rd ed.

[3] Canale, M and Swain, M. (1980) Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, 1, 1, 1-47.

[4] Carver, David. (1984) Plans, learner strategies and self-direction in language learning. System, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 123-131.

[5] Chamot, A. (2005). ‘Language learning strategy instruction: current issues and research’. Annual review of Applied Linguistics, 25, 112-130. Cambridge University Press.

[6] Chamot, A.U. & O'Malley, J.M. (1987). A cognitive academic language learning approach: A bridge to the mainstream. TESOL Quarterly, 21, 227-49.

[7] Clavel, Begoña (2005) Negotiation of form: Analysis of feedback and student response in two different contexts, Universidad de Valencia, Spain.

[8] Codina, Victòria (1998). Current Issues in English Language Methodology. Foreign Language Study. Studia Humanitatis Inc.

[9] Cohen, Andrew. (1996). Second Language Learning and Use Strategies: Clarifying the issues. Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition, University of Minnesota. Revised version.

[10] Corder, S.P. (1967). ‘The significance of learners’ errors’. International Review of Applied Linguistics 5: 1619.

[11] Ellis, Rod (1986). Understanding Second Language Acquisition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[12] Faerch, C. & Kasper, G. (1983). Plans and strategies in foreign language communication. In C. Faerch & G. Kasper (Eds.), Strategies in interlanguage communication (pp. 20-60). London: Longman.

[13] Faerch, C. & Kasper, G. (1980). Processes and strategies in foreign language learning and communication. Interlanguage Studies Bulletin Utrecht 5(1), 47-128.

[14]Gram, Susan (1987) ‘The effects of Detached and Embedded learning strategies on the process of illustrations in a self-instructional unit’ Concordia University, Canada.

[15] Griffiths, Carol. (2004). Language Learning Strategies: Theory and Research. Occasional paper No.1 (February). School of foundations Studies AIS St. Helens, Auckland, New Zealand.

[16] Hismanoglu, Murat (2000). Language Learning Strategies in Foreign Language Learning and Teaching. The Internet TESL Journal, Vol. VI, No. 8, August 2000

[17] Hsiao, TsungYuan & R. Oxford (2002). Comparing Theories of Language Learning Strategies: A confirmatory factor analysis. The Modern Language Journal 86 (2002).

[18] In-Sook, L. (2002) ‘Gender Differences in Self-Regulated On-Line Learning Strategies within Korea’s University Context’ Educational Technology Research and Development, Vol. 50, No. 1 (2002), pp. 101-111; Published by: Springer-Stable.

[19] Mayer, R. (1988). Learning strategies: An overview’. In Weinstein, C., E. Goetz, & P. Alexander (Eds.), Learning and Study Strategies: Issues in Assessment, Instruction, and Evaluation (pp. 11-22). New York: Academic Press.

[20] Naiman, Neil et al. (1978). The good language learner. (Toronto: Research in Education Series No. 7, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education).

[21] Nambiar, R. (2009) Learning strategy research we are we now? The Reading Matrix Vol. 9 N. 2 September 2009.

[22] Nunan, David (2003). Styles and strategies in the classroom. Plenary presentation. TESOL, Illinois Annual Conference, Chicago: March, 2003.

[23] O’Malley, J., Michael and Anna Chamot. (1990). Learning Strategies in Second Language Acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[24] O’Malley, M. et al. (1985). ‘Learning Strategy Applications with Students of English as a Second Language’. TESOL Quarterly 19 3), 557-584.

[25] Oxford, R. L. (1985) ‘A new Taxonomy for second language learning strategies’ Eric Clearinghouse on Languages and Linguistics.

[26] Oxford, R.L., & Cohen, A. (1992) Language learning strategies; Crucial issues of concept and classification Applied Language Learning 3, 1-35.

[27] Oxford, Rebecca and David Crookall. (1989). Research on Language Learning Strategies: Methods, Findings, and Instructional Issues. The Modern Language Journal, Vol. 73, No. 4 (Winter, 1989), pp. 404-419.

[28] Oxford, Rebecca L. & John Green. (1995). A closer Look at Learning Strategies, L2 Proficiency and Learning. TESOL QUARTERLY Vol. 29, No. 2, Summer 1995.

[29] Oxford, Rebecca L. (1990). Language Learning Strategies: What every teacher should know. New York: Newbury House.

[30] Oxford, Rebecca L. (2003). ‘Language Learning Styles and Strategies: An Overview’. Oxford: Gala 2003.

[31] Richards, J. C., & Schmidt, R. (2002). Longman dictionary of language teaching and applied linguistics (3rd ed.) England: Pearson Education Limited.

[32] Rigney, J.W. (1975) Learning Strategies: A Theoretical Perspective. In H.F. ONeil Jr. (ed) Learning Strategies New York: Academic Press.

[33] Rubin, Joan. (1975). “What the ‘good language learner’ can teach us”. TESOL Quarterly 9.1: 41-51.

[34] Segal, J., Chipman, S. & Glaser, R. (1985). Thinking and Learning Skills: Relating Instruction to Research. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

[35] Selinker, L. (1972). ‘Interlanguage'’. International Review of Applied Linguistics 10, 20930.

[36] Stern, H.H. (1987). Fundamental concepts of language teaching. Foreign language study. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[37] Stern, Hans H. (1975). “What can we learn from the good language learner?” Canadian Modern Language Review 31.4: 304-318.

[38] Tarone, E. (1977). “Conscious communication strategies in interlanguage”. In H. D. Brown, C. A. Yorio and R. C. Crymes (eds), On TESOL’77. Washington D. C. TESOL.

[39]Tarone, E. (1980). ‘Communication strategies, foreigner talk, and repair in Interlanguage”, Language Learning, Vol.30, No.2, 417-429.

[40]Tarone, E. (1981). ‘Some Thoughts on the Notion of Communication Strategy, TESOL Quarterly, Vol.15, No.3, 285-295.

[41] Tarone, E. (1983). Some thoughts on the notion of ‘communication strategy’. In C. Faerch and G. Kasper (Eds.), Strategies in interlanguage communication (pp. 61-74). London: Longman.

[42]Vinja Pavičić Takač (2008).Vocabulary learning strategies and foreign language acquisition. Second Language Acquisition Series. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters LTD.

[43] Weinstein, C. E. & Mayer, R. F. (1986). The teaching of learning strategies. In Winrock, M. (ed.) Handbook of research on teaching, 3rd ed. New York: Macmillian, pp 315-327.

[44] Wenden, Anita (1981). The processes of Self Directed Learning: A Study of Adult Language Learners. Paper presented at the Annual Convention of Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages. Detroit.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

Copyright (c) 2010 Matices en Lenguas Extranjeras

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

All content in this journal, unless otherwise noted, is under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Public License