Addressing Culture in the EFL Classroom: A Dialogic Proposal

El abordaje de la cultura en la clase de inglés como lengua extranjera: una propuesta dialógica

Keywords:

Interculturality, critical intercultural awareness, critical intercultural competence, dialogical process (en)Interculturalidad, conciencia crítica intercultural, competencia crítica intercultural, proceso dialógico (es)

Language teaching has gone from a linguistic centered approach towards a lingo-cultural experience in which learning a language goes hand in hand with the understanding of not only the target culture, but the learner's own culture. This paper attempts to describe and reflect upon a collaborative and dialogical experience carried out between two teachers of the Languages Program of Universidad de la Salle, in Bogotá. The bilateral enrichment of such a pedagogical experience helped the teachers to improve their language teaching contexts and prompted the construction of a theoretical proposal to enhance intercultural awareness. It also opened the way for the development of critical intercultural competence in foreign language learners.

La enseñanza de lengua ha pasado de un enfoque centrado en lo lingüístico hacia uno linguocultural, en el que el aprendizaje de una lengua va de la mano del entendimiento no sólo de la cultura objetivo, sino también de la propia cultura. Este artículo intenta describir y reflexionar alrededor de una experiencia colaborativa y dialógica que se realizó entre dos profesores del Programa de Lenguas de la Universidad de La Salle, en Bogotá. El enriquecimiento recíproco de esta experiencia pedagógica, permitió mejorar los contextos de enseñanza y la construcción de una propuesta teórica para promover la conciencia intercultural. También abrió las puertas para desarrollar competencia crítica intercultural en estudiantes de inglés como lengua extranjera.

Addressing Culture in the EFL Classroom: A Dialogic Proposal

El abordaje de la cultura en la clase de inglés como lengua extranjera: una

propuesta dialógica

José Aldemar Álvarez Valencia*

Ximena Bonilla Medina**

Universidad de La Salle, Colombia

*joseaedu@yahoo.com

**ximenabvonilla@gmail.com

Address: Universidad de La Salle Carrera 5 No. 59A-44- Departamento de Lenguas Extranjeras. Bogotá, Colombia.

This article was received on February 23, 2009 and accepted on July 10, 2009.

Language teaching has gone from a linguistic centered approach towards a lingo-cultural experience

in which learning a language goes hand in hand with the understanding of not only the target culture,

but the learner's own culture. This paper attempts to describe and reflect upon a collaborative and

dialogical experience carried out between two teachers of the Languages Program of Universidad de

la Salle, in Bogotá. The bilateral enrichment of such a pedagogical experience helped the teachers to

improve their language teaching contexts and prompted the construction of a theoretical proposal to

enhance intercultural awareness. It also opened the way for the development of critical intercultural competence in fl (foreign language) learners.

Key words: Interculturality, critical intercultural awareness, critical intercultural competence, dialogical process La enseñanza de lengua ha pasado de un enfoque centrado en lo lingüístico hacia uno linguocultural,

en el que el aprendizaje de una lengua va de la mano del entendimiento no sólo de la cultura

objetivo, sino también de la propia cultura. Este artículo intenta describir y reflexionar alrededor

de una experiencia colaborativa y dialógica que se realizó entre dos profesores del Programa de

Lenguas de la Universidad de La Salle, en Bogotá. El enriquecimiento recíproco de esta experiencia

pedagógica, permitió mejorar los contextos de enseñanza y la construcción de una propuesta teórica

para promover la conciencia intercultural. También abrió las puertas para desarrollar competencia

crítica intercultural en estudiantes de inglés como lengua extranjera. Palabras clave: Interculturalidad, conciencia crítica intercultural, competencia crítica intercultural, proceso dialógico [...] We are irreducibly unique and different,

and that I could have been you, you could have

been me, given different circumstances -in other

words, that the stranger, as Kristeva says, is in us

(Kramsch, 1996, p. 3).

Introduction

One of the major concerns of the Language Department of Universidad de la Salle is the emphasis in a more salient way of cultural aspects as a cornerstone in the learning of a foreign language. It is well understood that language and culture cannot be analyzed in isolation (Cortazzi & Jin, 1999; González, 1990; Hinkel, 2005, 1999; Peterson & Coltrane, 2003; Nieto, 2002; Stern, 1992). Several actions have been taken in order to set the context for this endeavor to happen. The Language Department in its areas of Spanish, French and English has developed the Cultural Literacy Project (CLP) whose aim is for teachers and students to build intercultural awareness through a critical stance towards all manifestations of culture. The CLP has engaged the Lasallian community in different tasks and activities such as a Reading Plan, different academic events such as the Faculty Week, the Cultural Thursdays, the celebration of the Day of Languages, among others. In the same way, teachers in every one of the subjects taught in the different abovementioned areas have devised and developed classroom-based projects that are centered on some cultural matter.

The endeavor undertaken by the Department has shown that culture and its teaching imply understanding and awareness of multiple axes. It is the interrelation of different axes that grounds the interdisciplinarity of the study of culture (Abdallah- Pretceille, 2001; Moran, 2001). In teaching and learning a language, interdisciplinarity becomes more evident when someone approaches a language in its contexts of cultural realization. As Peterson & Coltrane (2003) highlight, students cannot really master the language until they have also mastered the cultural contexts in which the language exists.

Being aware of the importance of culture in foreign language teaching-learning became our motor to engage in a collaborative and dialogical process. This explains why the concept of collaborative teaching achieves relevance in this experience. In what follows, we relate the experience and achievements of this collaborative work. Later, we present a theoretical proposal that fosters the approximation of culture in EFL teaching from an intercultural perspective. Finally, in the conclusions, we reflect upon the importance of teachers' collaboration in order to face the challenges that educational processes are posing such as the role of culture teaching in learning a language.

Dialog and Collaboration as a Route for Teachers' Professional Development

At the beginning of the second semester of 2007, we were assigned to teach two different subjects. One of us was given the class "Cultural Awareness", whereas the other was in charge of "Mastering English Language Skills"1. The first course focused on the study of culture and the second on language skills. At the beginning, we did not set out to engage in any collaboration to undertake our pedagogical task; nonetheless, in an informal way we started sharing our views and the daily experiences we were going through in our classes. Little by little, we introduced changes in our teaching situations on the basis of the regular discussions about how culture may be tackled. We started doing some readings and sharing them in order to enrich our conceptualizations and to make better informed decisions.

It was only at the end of the academic semester that we rationalized that we had been engaged in a collaborative process and that it could lead us to articulate a final product. Edge (1992) calls cooperative development to the process we unconsciously carried out. This author points out that there are two different levels in which teaching can be a growing professional experience. One goes from an individual reflection from daily practice and the other from the supervision and insight of members of the institution where teachers develop their teaching activity. Nevertheless, when these levels are restricted, teaching development could be better enhanced through dialog, discussion, and cooperation with others. The collegiate interaction between teachers usually helps professional practice development in two ways: First, it goes beyond egocentric subjectivity to cause teachers to be clear in their own experiences and opinions. Second, it does not leave that responsibility to the administrative staff since "when professional development push comes to administrative shove, it is the professional items which tend to disappear off the end of the staff-meeting agenda" (Nunan & Lamb, 1996, p. 55).

Within the development of this cooperative task, we engage in what Kim, Chin & Goodman (2004) call informal critical dialogs, which helped us to achieve understanding of several issues. As a result, we built a proposal, initially theoretical, and systematized some of our discussions and reflections. The next section concentrates on the description of the two classes that constituted the source for us to develop our collaborative and dialogical engagement. To achieve the task proposed, we describe some of the activities developed in our classes and use samples taken from students' written production in order to exemplify the achievements of our work.

Addressing Culture in the EFL Classroom: The Experience in Cultural Awareness

The following is the description of the experience that was carried out in the course "Cultural Awareness". It was a class introduced recently in the Language Program at La Salle University. The general intention of the institution in proposing this class was to increase students' awareness of the aspects of culture when learning a foreign language. The class also aimed at studying general cultural features of English speaking countries as a main goal to be achieved throughout the course. However, describing a culture from an observer position was a superficial job which did not account for the complexity of the role of language educators who are studying to be teachers. Byram & Risager (1999) state that teachers act as mediators between cultures. This involves the responsibility to help learners to understand other peoples and their cultures. Thus, based on the discussions we held on our focus on interculturality, we agreed that, as mediators between cultures, we needed to foster in our students a critical approach to culture. From our viewpoint, students should take a critical position which could not only be based on the judgments about the target culture but also on the analyses and understanding of their own culture.

A major complexity in discussions of culture is that people hardly ever have the chance to examine the influence of their own cultural background as regards their behavior (Brislin, 1993). Similarly, Lado (1998) refers to culture as "the ways of a people" and in connection to people's attitudes towards culture, he explains that "...more often than not the ways of a people are praised by that same people while looked upon with suspicion or disapproval by the others, and often in both cases with surprisingly little understanding of what those ways really are and mean" (p. 52).

By reading Brislin & Lado's definitions as well as Abdallah-Pretceille (2001), Byram (2000), Cortazzi & Jin (1999), Hinkel (2005), Kramsch (2001; 1998; 1993), and Paige et al. (2008), we can infer the necessity of an intercultural approach to cultural practices. In the context of language teaching, teachers should enhance the development of cultural awareness in order to promote intercultural speakers. In this regard, Kramsch (2002) clarifies that an intercultural speaker is a tolerant and openminded person who is able to interact with other cultures taking into account cultural differences. Inspired by the different readings we had discussed, we agreed that a good exercise to reach the goal of promoting intercultural speakers was to propose tasks through which students questioned their impressions about other cultures and examined how cultural representations were partly the product of their own native culture. This is how we decided that the class of "Cultural Awareness" should base its development on a three-stage structure to be worked out along the semester.

In the first stage we aimed to recognize the students' understanding of culture and the elements that underlay those conceptualizations. This stage included activities of retrospection and analyses of their own life experiences as well as readings that guided them to reflect on those issues. In general, the students showed their understanding of culture resembling Hebdige's (cited in Strinati, 1995, p. 15), whose definition of popular culture asserts that it is "a set of generally available artifacts: films, records, clothes, TV programmes, modes of transport, etc. or a list of behaviors and products that are part of the identity of a group of people". Some students considered culture to be related to intellectual growth, mainly the works and practices of intellectual and special artistic activity (Storey, 1996). They also placed special attention on the fact that culture and language are extremely related and it is difficult to determine whether culture defines language or language defines culture since there are arguments on both sides. In this regard, we agree with Moran (2001), who suggests that language is the means to manipulate or use varied cultural products or it is also the tool to nominate and understand the perceptions, values, attitudes, and beliefs that rule ways of life. For this reason, in this stage students analyzed samples of interaction in the target language and inquired about ideologies involved in the performance of those behaviors and how, as members of a community, they could contribute to the development of cultural artifacts.

In addition, the students were able to recognize the fact that language in contemporary multicultural communities fosters the transformation of new generations as well as their perceptions of the world. Pavlenko & Blackedge (2004, p. 2) connect their argument to this idea by asserting that "the shifts and fluctuations in languages available to individuals have become particularly visible in the light of recent sociopolitical and socioeconomic trends: globalization, consumerism, explosion of media technologies, and the postcolonial and post Communist search for national identities". Globalization and media have produced new ways for people to learn about other cultures and simultaneously build or strengthen stereotypes and prejudices (Brown, 2000). The students realized that stereotypes and prejudices can model one's understanding of a culture and are crucial for making sense of one's own beliefs before attempting to evaluate and understand others' behaviors and views. Finally, students discussed the idea that being an intercultural speaker is a privilege, in agreement with the perspectives posed by Kramsch (2002), in which she acknowledges the advantages of having access to cultures from an intercultural stance.

In the second stage students were more concentrated on the features of culture that could be observed in communicative interactions in different cultures and the way these interactions could be compared. Elements such as nonverbal communication, personal relationships, family values, educational attitudes, work values, time and space patterns and cultural conflicts, among others, were the focus of discussion and reflection (Levine & Aldeman, 1982). Broadly speaking, students studied the way in which these elements were represented by each culture (some English speaking countries and Colombia in particular), the importance people grant to them and how the elements could be tackled from the perspective of a competent intercultural subject (Rowena & Furuto, 2001).

The last stage was probably the most important for this experience because students manifested more clearly their perception of intercultural competence. This stage consisted of students' development of a final project where they had to select an aspect of culture which they considered worthy to work on because it was controversial, it was related to a personal conflict, or it generated general interest. The origin of students' inquiries was the result of classroom discussions on topics linked to the culture of English speaking countries and the comparison of those cultures with the Colombian culture.

Although this is called the third stage, it is important to clarify that it was developed all along the academic semester; therefore, it overlapped with the previous stages. It was carried out in three steps in which the first started as a project proposal followed by an preliminary report in the second step and, as a final step, students handing in a paper and sharing the outcomes with the class. The project could be developed about the culture and cultural element that students preferred to analyze. It was mandatory to show evidence of the analysis done and connections with theoretical support.

Students' proposals were the beginning of an analysis to figure out their interests in aspects of their own culture since ninety percent of the topics were chosen on issues about their cultural milieu. For instance, students decided to work on vegetarian culture, lesbian culture, body-building, urban cultures, regional culture (Caribbean coast) which dealt with the Colombian context. They were also attracted by the comprehension of connections among cultures; for example, the idealisms as regards foreign cultures of Colombian students at university. Students presented a particular interest for collecting information on how the individuals in those cultures thought, how ideologies were visualized in their actions and how they, as foreign people, were perceived by others. Overall, most of the projects attempted to identify ideologies evident on specific behavior or cultural representation observed in each culture or subculture.

In the second step of this last stage, students showed their advances of their proposals. They presented a more structured idea of what they wanted to do and most of them showed, as a tendency, a general concern for working on the stereotypes they had about subcultures. Students realized these subcultures were at times rejected or even neglected because their members behaved or thought differently from the standard behavior recognized and accepted by the community. An example of this was the significance given by a group to the different youth subcultures which are judged as violent or even asocial only because they dress differently or listen to a different kind of music. Students reported that a single event can label a group of individuals and cause negative effects. They wrote in their proposal paper2:

This project is done on based on the past situation in which a young boy was killed when he was in his way out of a little concert... This boy got into a fight with... Skinheads...and the boy died because of this attack. This generated a big controversy and prejudices and stereotypes about the skinhead boys. They are seen now as dangerous people, armed people with bad intentions, criminals...They are generalized as threats but it is important to know that skinheads are not the way people think ...without knowing information about them and without respect and tolerance...

In this excerpt, we can see that the students' project was useful as an excuse to develop a general understanding of an event that happened in their surroundings. The students shared some time with a group of skinheads and tried to delve into their life experiences to be able to understand the reasons for their actions and to help other people understand them as well. Consequently, students reached the conclusion that people's attitudes toward subcultures like skinheads mostly came from generalization: "They are generalized as threats", that created "prejudices and stereotypes". Through their study they intended to contribute to the skinheads' integration in society as common members that comprise part of it. Finally, it is important to notice that students' reflections indicate a level of intercultural awareness in which tolerance appears as a central element. This inference is sustained in two ways: First, because of the attitude students had of trying to understand the skinheads' subculture, and second, because to some extent in their paper they advocate for more tolerance and respect for this cultural group, as shown in this excerpt: "[...]people speak of them without knowing information about them and without respect and tolerance..."

Another project that caught our attention intended to inquire about vegetarians. The group working on this topic tried to scope the reactions vegetarian people have about non-vegetarian food in social meetings; students wrote:

This research project is made in order to understand what is the vegetarian culture, which are their beliefs, but it is most focused in understand which is the common behavior of that people when they have to confront the meat in a social meeting, or the comments of the others according to their believes.

The students' proposal shows that they were aware of the importance of understanding other people's cultural patterns, in this case, vegetarians. Notice here that students use the word "understand", a term that is significant when we refer to interculturality. In this project, vegetarians constituted the target to observe and understand in connection to the way they behaved in environments where they interacted with non-vegetarians. Thus, students wrote: "[...] It is most focused in understand which is the common behavior of that people when they have to confront the meat in a social meeting". Students also intended to explore vegetarians' beliefs and others' opinions which, in essence, could visualize prejudices about this group. Broadly speaking, students did not only center on understanding this subculture from the outsider perspective but from an insider perspective. This explains why they consider it paramount to know their beliefs.

Another work that is worthy of mention is the one a student developed on the bodybuilding culture. He was 22 and liked practicing body building. He tried to show the influence of American fashion by analyzing the different strategies for such a practice. Additionally, he established a comparison between the cultural practices regarding this topic in Colombia and the USA specifically. He wanted to explore ideological issues around body building regarding health, economic and cultural constructs. This case is a key example of how the students started to acquire a critical position to question their own choice for living. Even if this young man was a fan of this sportive practice, he considered it crucial to be aware of the reasons people choose it. Through his practice of this sport, he thought that the American culture had certain influence on people's choice and he decided to uncover the positive or negative elements underling this influence. All in all, this project evidences that being critical about the influences that lead us to make choices for our cultural practices was another form to build interculturality.

In general, students felt they could observe other people's behaviors to understand how the others' imaginaries affected people's ways or choices for life. They thought that through the understanding of cultural practices, they could also be able to see themselves in the eyes of others. In this account, one of the students wrote in one of the projects:

Our reality always has been from the exterior, from we observe, we leave ourselves to go for the decisions of others, we have created a world and without stopping to see with depth, certainly we don't give ourselves the opportunity to know the cultures and people as actually they are.

These comments as well as the reflections developed in their project enable one to see that there is a sense of interculturality in the way students are reading their environment and cultural subjects embedded in the foreign and native cultures. That is why students admit that "we don't give ourselves the opportunity to know the cultures and people as actually they are..." Generally speaking, this experience, along with the majority of the projects students developed, was a way for them to know more about themselves (notice the use of "we" in the above samples) and to question their stereotypes and imaginaries. It can be said that by looking at the Other from an intercultural perspective, they were able to see and inquire about themselves.

Another example as regards reflection on stereotypes and cultural understanding was a group which was interested in lesbian culture. They wanted to examine the way heterosexual people perceive this subculture and the kinds of stereotypes and prejudices attached to homosexual practices. They said:

When people talk about lesbian culture think that this "kind" of women is very different than another people, and they are a lot of prejudices and stereotypes about these women, but it is very interesting to see that lesbianism is not an illness.

At this stage, these students had realized that although we are supposed to be in a more opento- diversity epoch, many of these prejudices and stereotypes keep these cultures in a hidden space (lesbianism as an illness). Additionally, students became conscious through their study that stereotypes increase differences among people (this "kind" of women is very different than another people); they concluded that dissimilarities obeyed the imaginaries created by people. Although imaginaries are not founded on clear criteria, they can constitute a reason to detach people from cultural interaction. These worries coming from students reflected how they were increasing their level of tolerance in their actions and how this phenomenon was linking them to a more intercultural perspective vis-a-vis culture learning. They refused to act by following everybody's patterns of rejecting the group of lesbian subculture and decided to explicate how prejudices determine limitations in interactions with groups like the one under study.

In the last step of the development of the project, students presented the results coming from the analysis of the data they had collected. The students found that stereotypes and prejudices are common factors that play a role and model the different interactions and behaviors between members of different cultures. The concept of modeling is relevant when we look at intercultural connections. This is well exemplified when we think of body building practices. For instance, the student that worked on this topic found that most of the subjects that are part of these routines follow the general tendency of American people who want to show themselves in "better fit" and they follow strict American recipes or behaviors presented on TV or in well known magazines. He brought into being that these "bodybuilding practitioners take medicines to increase their muscles and pay huge amounts of money to do so". However, "they do not consider these practices wrong but necessary because famous artists also apply these strategies to look well". The conclusions drawn from this study helped this student understand that the invitation to follow famous models was a commercial strategy coming from American advertising that attracted people to consume and become addicted to the gadgets, medicines or any product associated with this sport. At this point, it can be concluded that this ethnographic task helped the student to discover that some cultural practices are related to socio-economic issues.

In the case of the group that worked with the lesbian culture, they pointed out that people need to open their minds to new subcultures that are emerging nowadays. Based on a multicultural view (Pavlenko & Blackedge, 2004), the students reported that "people should not talk about men and women but about humans who have no sex difference or tendency". This exploration ended up with students advising people on the ways subcultures can be seen; this advice is expressed through the words "people should". For these students, eliminating the dichotomy men and women might help societies adopt a more tolerant perspective in which all of us are humans with no gender differences. This consideration shows not only the level of tolerance they developed but also their worry about getting other people conscious of intercultural skills to approach other cultures which are usually neglected, like the lesbian subculture.

We concluded that these projects were very helpful for the students to become aware of the importance of cultural awareness and interculturality in the study of a foreign language. They found more explicit relations between language and culture. The analysis of interactions between Spanish speakers and English speakers aided students in identifying aspects that connect culture to language; for instance, roles of speakers, space management, registers, styles and language variety. As a result, students viewed that reflecting and studying their native language and a foreign one are catalysts to understanding their own realities as well as others' realities and cosmovisions. They also conceptualized that trying to understand another culture implies a stripping of prejudices built up by the society in which they are immersed. They could examine negative and positive stereotypes which can make people approach or reject a culture. Finally, the condition of the postmodern epoch implies being open not only to understand the others' cultures and our own, but also the changing realities that directly impact worldwide cultures and subcultures.

The Experience in Mastering English Language Skills

The experience in this class varied in that, unlike "cultural awareness", this one focused on the development of language skills (listening, speaking, writing, etc.) rather than the explicit study of culture. However, we accepted the premise that "language and culture are inexorably intertwined" (Gladstone, 1980, p. 19) and that it is one of the major ways in which culture manifests itself (Kramsch, 1993; Hinkel, 1999; Nieto, 2002; Peterson & Coltrane, 2003, Stern, 1983, 1992). Due to the differences between the two courses we were teaching, the first one more content oriented whereas the other more language oriented, we agreed that for the class -"Mastering English Language Skills"- there should be a languageas- culture approach as a way to go beyond the traditional language-and-culture or culture-inlanguage approach (Kramsch, 1996).

The textbook provided for this subject served the approach that was adopted because of its cultural orientation. Movies, comics, documentaries, music, literature and other materials would always set the context to reflect upon cultural issues linked to linguistic contents. Intercultural awareness was enhanced through discussion of the cultural diversity which is evidenced when two languages are rethought in their contexts of realization. Students interweaved the reflections they were making in their "Cultural Awareness" class and the tasks they were carrying out in "Mastering Language Skills". These connections were evidenced in the discussions that were held in class about life- styles in different cultures, values assigned to certain behaviors or life attitudes, among others.

Coming from the collegial dialog established between us, and after consulting on it with students, we all agreed that the final assignment for the writing process would be an opinion essay on one of the books students were reading for the class: A Room with a View (Forster, 2003). Through this task, they were supposed to join concepts and reflections studied in both subjects in order to choose, describe, analyze and give arguments to understand any cultural issue identified in the literary text.

The task proved to be successful. Students showed that new perspectives to approximate culture were permeating their personal views. Going beyond the traditional inmanentist or biographical approach to addressing literature, they drew upon a sociocultural view (Eagleton, 1983) which presented a broader perspective and allowed for better understanding of cultural texts. For instance, some students analyzed the role of women in the socio-cultural context of the XX century. One student says: "The Room With a View story is not far from the reality of many women at the... beginning of the XX century when they were repressed by society". Through this sample, it is noticed that the student is making connections with the concept of interculturality in which cultural patterns (women's repression), views, events or behaviors should be seen and analyzed as social practices which are located in specific historical moments and settings. This contention is strengthened by another student who asserts that to understand Lucy Honeychurch's character, it was necessary to bear in mind that "the values, the beliefs, customs, politics, religions, ideologies, language, etc. are important elements that determine culture". In the same vein another student writes: First I am going to emphasize the English woman during that era: ...women still had very few rights and a different conception in 1900,... they stayed at home to take care of children..." Notice that the analytical perspective of these students implies an intercultural view in which any interpretation of a culture should come from the study of the internal dynamics (Geertz, 1973) of that culture in all dimensions, "values, the beliefs, customs, politics, religions, ideologies, language", as stated by the student.

Some other students related the story portrayed in the piece of literature to current dynamics of societies; for instance, one of them asserts: "Nowadays, the prejudices about the different social classes and the lifestyles don't let society notice the reality". This excerpt shows the students' understanding of the negative role of prejudices in current societies. Besides indicating his understanding and interest in this phenomenon, the student's discourse implies a direct connection with the topics discussed in the class of Cultural Awareness. In this regard, we can cite one student that addressed the concepts of cultural shock and components of culture: In the book A Room with a View, Lucy Honeychurch visits Italy, where she meets different kinds of people. They have a different culture. Lucy and her cousin Charlotte Bartlett have to get accustomed to a new life; the food, clothes, houses, people, etc. are different. They enjoy it but they are sad because they remember the city and its customs". Although this student does not thoroughly discuss her statement, she is aware that the new cultural features of another country (food, clothes, etc.) can cause cultural shock which can be experienced through feelings like sadness. There is an understanding that cultural shock happens due to a new cultural experience and is intensified by the background of one's homeland culture. Despite this fact, the student acknowledges that there needs to be a process of acclimation to the new culture as Lucy and Charlotte depict it in the story.

Traces of the understanding of intercultural awareness and intercultural competence can be identified in students' papers; for instance, one student in relation to Lucy Honeychurch's experience wrote:

[...] when we arrive to a new country, it is common to find difficulties relating to believes, habits, attitudes and behaviors, in conclusion the cultural differences...However to learn about cultural differences is an essential culturally competent attitude where we could appreciate and respect a cultural diversity...it is important to know the other worldview.

This excerpt reveals that in order to approximate another culture it is essential to acknowledge the Otherness (it is important to know the other worldview); in other words, the understanding of the existence of diversity and a respect for it. We think the student points at two main concepts that are at the core when one talks about intercultural awareness and intercultural competence: the comprehension of my "Myness" and the "Otherness" and the assumption that interculturality has to do with an attitude that permits one to "appreciate and respect a cultural diversity".

Showing examples of all the different ways in which students in this class connected knowledge acquired in both subjects goes beyond the possibilities of this document. Nevertheless, the samples presented and the different discussions held in class allow one to see that students were transcending from descriptive to a hermeneutic way of reading a cultural text such as a novel. The experience described only represents a first attempt to make culture meet ends with language teaching. The idea of introducing the concepts of interculturality and intercultural awareness emerged along the dialogic process we experienced. Nevertheless, it was still a timid approximation which needs to be strengthened in future experiences. Furthermore, we are aware that a more critical stance is required as a basic condition to foster the critical subjects that education advocates. This last contention led us to think, initially, of a theoretical proposal which focused on the development of critical intercultural competence in our teaching context. The next section presents the description of such a theoretical proposal.

A Framework to Understanding the Development of Intercultural Competence

The conceptualization we display here emerges from the dialogic process we undertook and the multiple readings that have enriched our construction. Through this section, we intend to outline our understanding of some paramount concepts and introduce a theoretical model that might enlighten ways to approach culture in the foreign language classroom in order for our students to achieve critical intercultural competence.

The concern in regard to the relevance of culture in the ELT profession is relatively new. According to González (1990) and Ommagio (1986), the issue of seriously infusing cultural goals into the curriculum dates back to the 1970s. Several perspectives were advocated in order to "learn" the culture of the target language, for instance Brislin (1993), Cortazzi & Jin (1999), González (1990), Gudykunst & Ting-Toomey (1988), Kramsch (1996), Lustig & Koester (1999), Moran, (2001), and Ommagio (1986) pinpoint that in many cases the core was the study of cultural products: literary works or works of art. Another perspective addressed culture as the acquisition of background information: factual information about history or geography, celebrations and so on. Culture was also addressed on the basis of the observable behavior, beliefs, values and attitudes of people. Some other authors considered it as the social heredity of a group of people or as communication.

In order to go beyond the limited notion of culture, we see in France in 1975 that a new perspective to understanding culture appeared. It is how the term "intercultural" started being used to refer to social and educational actions that dealt with immigration affairs. Soon the concept impacted the foreign or second language teaching curriculum. The intercultural approach advocates a new way to conceptualize culture, the subjects, the context and interaction. It has given birth to other concepts such as cultural awareness, intercultural communication and intercultural competence. Next we intend to address some of these concepts as a manner to locate our proposal rather than with the aim of reviewing the myriad of definitions appointed to them.

The Stance of Interculturalism as the Recognition of Myness and Otherness

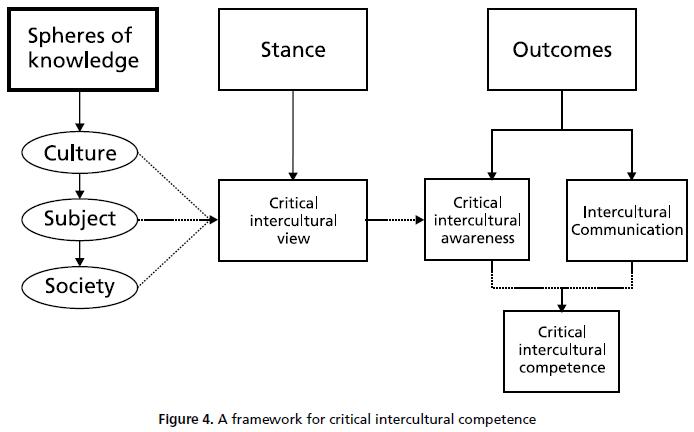

Before tackling interculturality, it is paramount to locate our comprehension of culture. It is now clear that culture is not a monologic phenomenon due to the fact that its reading requires the conjunction, interrelatedness and interaction of several disciplines, as we have stated above. It is not a monolithic or a static phenomenon; on the contrary, dynamism is one of its main features. In view of this, culture is a sphere of knowledge (Ramírez, 2007) in which the frameworks of assumptions, ideas and beliefs that can be used to interpret people's actions, patterns of thinking and human artifacts (art, literature, etc.) lie at the core. This sphere allows us to know and comprehend the world and is usually more linked to the concept of inheritance; hence, it is daily updated in another sphere of knowledge: society. Culture and society overlap and engage in tension themselves while at the same time strike another sphere of knowledge –the individual, the socio-cultural subject. Individuals are in between and are pulled by the strings of these two forces. In short, the sphere of culture is in constant updating and struggling in the context of societies; societal dynamics are constantly challenging cultural knowledge, reshaping or making up new understandings. Individuals rely on these spheres to build themselves as social and cultural subjects; however, simultaneously they will use these spheres to constitute the sphere of the subject, the sphere of the Myness.

The view of culture in language teaching from an intercultural perspective supposes a progression from monological to dialogical views to understanding culture. These monological views materialize in two ways. The first one approaches the target culture from ethnocentric inspection in which the culture of the language learner is at the core to interpret and describe the host culture (Brislin, 1993; Oliveras, 2000, see Figure 1). The second approach, in contrast, shows that in some stages of foreign language learning, the language learner adopts to a certain extent the ways of thinking and the behavioral patterns of the target culture and uses these to judge and think of his/her natal culture (See Figure 2); s/he intends to "unanchor" aspects of his/ her culture of origin3. Such a situation often carries implications to the way learners assumed their linguistic and cultural identity. We must remember that people's cultural identity is based on the relation between an individual, society and culture (Damen, 1987; Hinkel, 2005; Lustig & Koester, 1999), and implies that dilemmas of identity will not only impact the way an individual sees his/her own culture and society but the way s/he perceives himself/herself. As we have seen, the monological views presented a biased and fragmented reading of the cultures in interplay; it is due to this reading that an intercultural perspective attempts to encounter both ways of approaching culture (See Figure 3).

One of the main elements that articulate the concept of interculturality in language teaching relies on the fact "that many aspects of second and foreign language learning are affected by the interpretative principles and paradigms in learners' natal culture" (Hinkel, 2005, p. 6). Consequently the understandings, conceptualizations and constructs of the target culture are fundamentally affected by students' culturally defined worldviews, beliefs, assumptions and presuppositions. This suggests the need for a perspective that accounts not only for what the other culture and its cultural subjects are, that is the Otherness, but also who I am as a cultural subject; in other words, my Myness. In this sense, the prefix inter has to do with the way the Other is seen and I see myself; it refers to the establishment of an interaction among social groups, individuals and identities (Abdallah- Pretceille, 2001; Byram, 2000; Porto, 2000). In light of this, the concept of interaction becomes relevant under the intercultural approach since the emphasis will be given to the encounter of cultures, subjects, systems of thought, social practices and the conditions of possibility (Foucault, 1984) that configure these interactions.

The dialogic dynamic between identity and Otherness helps visualize the sphere of culture in relation to society and the subject. The interaction among these three spheres calls upon different disciplines to explain the concept of interculturality. Although these interdisciplinary relations go beyond the scope of this paper, it is necessary to mention that the intercultural approach borrows constructs from disciplines like philosophy (phenomenology), sociology (comprehensive sociology and interactionism), anthropology, social psychology (representations and categorizations), linguistics, sociolinguistics (ethnography) and cultural studies, among others (Abdallah-Pretceille, 2001; Byram, 2000; Moran, 2001).

Bearing in mind that culture is inescapably permeated by relations of power and politics (Byram & Feng, 2005; Kramsch, 2001, 1998, 1996; Storey, 1996), we assume that besides approaching culture from an intercultural stance, its study can be enriched if a critical perspective is adopted. A critical intercultural view will draw upon an analysis of cultural texts4 as a way to uncover ideologies which allow discussion and study of discursive formations (Storey, 1993). These discursive formations will emerge from the scrutiny of the discourses that lies beneath the cultures that engage in interaction, the subjects and the wider society; that is to say, it will be seen how the spheres of knowledge come into play in specific and situated contexts.

A critical intercultural approach will aim to develop critical intercultural awareness. Usually cultural awareness is defined as the ability of interlocutors to acknowledge and understand the differences between their schemata (patterns of thinking, behaviors, beliefs, assumptions, etc.) and the schemata of the foreign interlocutors (Brislin, 1993; Byram, 2000; Cortazzy & Jin, 1999; Damen, 1987; Porto, 2000). In light of a critical perspective, the use of the concept of difference would be replaced by diversity. More than seeing the Others from the stance of the difference, we should start to see the Myness and the Other's essence and features as the product of the diversity that is inherent in human beings. Awareness has to do with the acknowledgment, tolerance and acceptance of that diversity and the ability to reflect and evaluate it critically. It will let the individual explore, question, examine and strengthen his/ her cultural identity rather than undermining the importance of his language, culture and so on in front of another culture. Moreover, an individual will be open-minded to read other cultures and speakers of other languages in order to make sense of their diversity and particular identities.

A critical intercultural approach will not only ensure the development of critical intercultural awareness but also intercultural communication5 competence. Notice that the first term establishes the view which will be the lenses to approximate a phenomenon: culture. The second term indicates an attitude towards that phenomenon. The last term is located in the dimension of action; that is to say, how a speaker can interact in any context as an intercultural subject in order to create shared meanings (Lustig & Koester, 1999). This will represent the materialization of interculturality and intercultural awareness in a discursive situation. Clearly, to successfully accomplish the conditions for intercultural communication, interlocutors will need to be acquainted with the formal aspects of language (phonology, phonetics, syntax, etc.) and put into practice sociolinguistic, discursive and strategic competences (Canale & Swain, 1996a, b; Oliveras, 2000; Savignon, 1997). As a whole, a critical intercultural approach aims to have two outcomes: the first to enhance critical intercultural awareness and the second to develop intercultural communication competence. These two outcomes will fundamentally give rise to a broader concept: critical intercultural competence6.

We consider that the field of language teaching should ultimately aim to achieve a competent intercultural subject who transcends the simplistic description and naïve interpretation of the Other culture; instead, s/he will move toward a critical approximation to it. Byram (1995, in Oliveras, 2000) states that intercultural competence should embed savoir-etre, meaning a change of attitude. Savoirs, ability to acquire new concepts, and savoir-faire which refers to the activity of learning through experience. In the framework of a critical perspective, learners' change of attitude would be bi-directional, in the sense of assuming new views in front of his/her own culture and the target one; namely, a comprehensive, informed and critical attitude. This would lead to critical intercultural awareness.

The learning of intercultural competence has been researched and experimented through different models. Oliveras (2000) discusses two of the most predominant models to intercultural teaching, to wit: The Social Skills Approach and the Holistic Approach. The former sees intercultural competence as the ability to behave properly in an intercultural encounter. The speaker must simulate the social skills native speakers show as representatives of any given culture. The latter defines intercultural competence as an attitude towards the other(s) culture. In general this approach takes into account issues such as the role of personality and identity. Through this competence the individual can stabilize his/her own identity during intercultural exchanges. The development of empathy constitutes another aspect that will permit understanding, tolerance and respect for different cultural views.

Although we agree with the standpoint presented by Oliveras (2000), we consider that the critical perspective needs to take explicit part in the study, teaching and learning of any culture. Researchers such as Byram & Feng (2005); Fairclough (1995, 1989); Kramsch (1996, 1993); Mejía (2006); Nieto (2002), and Pennycook (2002) sustain that foreign language teaching needs to place emphasis on critical understanding of current thought in both the linguistic and socio-cultural sciences. Besides the affective, cognitive and communicative component, it is necessary to talk about a critical component to define intercultural competence. The link between language study and critical cultural analysis needs to be articulated in order to encourage students to assume a critical understanding of the sociocultural phenomena. To achieve this, it is essential to bear in mind that any cultural text or artifact is made up of discourses which are underpinned by ideologies which materialize forces of power and control (Fairclough, 1995, 1989; Fowler, 1983; Kramsch, 1996, 1993; Pennycook, 2002; Storey, 1996, 1993; Strinati, 1995; Van Dijk, 2000a; 2000b).

So far, we have described and conceptualized the fundamental axes that structure our proposal to tackle culture in FL teaching. This conceptualization and the theoretical framework that has been depicted constitute a blueprint of an approach to a line of inquiry that has emerged from the process of a collaborative and dialogical interaction we established in the context of our classes. In this last part, we would like to make a direct link to the innovative teaching practice that gave birth to this theoretical model. We will use the connections made to summarize what has been discussed along this section through a figure which locates and puts into interaction the different components of the framework proposed:

The development of the classes and our discussions helped us start shaping the idea that an individual is immersed in different spheres (See Figure 4). Along with students, we discussed that humans moved among spheres of cultural knowledge, society, and interactions with other subjects. In their projects and the analysis of a literary work, students admitted that subjects are both the product and producers of culture and society. Their exploration of lesbian groups, vegetarians, or the role of women in Edwardian English society and culture of the XX century, placed the individual at the core of any cultural and societal phenomenon. For instance, one student in his essay discusses the several internal tensions that Lucy Honeychurch -the main character of the novel A Room with a View- faces when cultural traditions and social dynamics force her to acquire the traditional role women were granted at the time. The student writes: "In a room with a view the Lucy's character felt offended by the way that society treat ...women were educated to be housewives and to take care of her husband and children, if they wanted to be someone different they will be judged by society". This example emphasizes that the cultural and social patterns are in interaction and act upon individuals, usually engaging into frictions and struggle; this conclusion is strengthened with the next excerpt: "Lucy...fights against her family and friends to obtain her woman's rights, to be free and acquire the independence to be what she wanted".

Throughout this innovative teaching contribution, we realized that it was necessary to establish a stance (See Figure 4) that would constitute the lenses through which we approached the spheres of knowledge. As stated above, we assumed a critical intercultural view. This is the perspective under which most students' projects were developed. One example to illustrate this assertion is portrayed in the comparative study done by the student who concentrated on the body building cultural practice, in Colombia and the USA. His reflections pointed out that economical and social imaginaries around physical appearance are the main agenda in the North American body building practices. Finally, the student calls attention to the fact that the North American body building cultural practices have been adopted as a model in Colombia.

Based on students' reflections and analyses, we concluded that the outcome (See Figure 4) of a critical intercultural stance should be the development of critical intercultural awareness and, at the same time, intercultural communication. This is what we observed in the view students had of their own culture and the foreign one. By interacting with different subcultures (lesbian, bodybuilders, etc.), students achieved awareness that allowed them to evaluate a cultural practice from inside and outside. They needed to make use of intercultural communication skills in order to get by in different communicative situations. The various explorations of cultural practices were the context for them to build up critical intercultural competence.

As we have exemplified in the description of the two courses we taught, the most important gains of the intervention were that students constructed a sense of interculturality and intercultural awareness in order to approximate not only the foreign but their native culture. Thus we have presented the conclusions obtained in each pedagogical experience and we have connected the achievements that proved to be similar after analyzing students' productions from each class.

Conclusion

One of the main reflections pointed out through this experience is that collegial dialog is an important source of teachers' professional development. Teachers should be aware that practical experiences coming from their colleagues constitute a resource for their personal and professional growth. Although at the beginning we did not set out to embark on any collaborative and cooperative task, the dynamics of our dialogic process prompted the decision that this experience needed to be systematized and shared with the academic community. Our experience reveals that for cooperation and dialogue to happen, participants' attitude and openness to new viewpoints play important roles.

In regard to culture, it is paramount to mention that it still needs wider exploration and reflection in the area of foreign language teaching in our country (Badillo, 2006; Real, 2007), yet Colombian referee journals show that there is an increasing interest in researching on the topic of culture teaching-learning, interculturality, cultural awareness and bilingualism, amongst others, directly related to cultural issues (see recent studies carried out by Ariza, 2007; Campo & Zuluaga, 2000; Cruz, 2007; De Mejía, 2006; Mojica, 2007; Posada, 2004; Quintero, 2006; and Velásquez, 2002). Especially at the university level, new strategies are being employed to connect culture and language learning, such as the case at Universidad de la Salle. We also consider that a critical stance needs to be adopted if we are to foster intercultural subjects that can understand and take action in front of the hidden agendas of postmodern societies.

Through this paper we advocate the exploration of new ways to articulate culture in the EFL class, not only at the university level but also in other language teaching contexts. This paper has shown two plausible examples of how the cultural component can be articulated in programs in charge of educating language teachers. Our experience demonstrates that the role of teachers change –they become mediators in the exchange of cultures. We believe that this role is not difficult to play if teachers are open to dialogue and to encountering new perspectives. We hope our collaborative and dialogic experience might constitute a source for teachers to generate new dynamics of interaction in which the discussion of interculturality in language teaching plays a central role.

1 The students that made up part of the experience were in seventh semester of the Language Program at Universidad de la Salle. It was a mixed gender group of students whose ages ranged from 21 to 28 years old.

2 The excerpts that will be presented along this document were not edited by the authors and thus may contain some grammar mistakes.

3 This phenomenon only constitutes a phase in language and culture learning since identity is not fixed but on the contrary is "a contingent process involving dialectic relations between learners and the various worlds and experiences they inhabit and which act on them." (Ricento, 2005, p. 895). Consequently, it is possible that new re-articulations of learners' identities happen through linguistic and cultural contact (Holliday, 1994; Kramsch, 1993).

4 In our stance, text is understood as anything that can be read; thus, an artifact like a painting, a social practice or an oral utterance will make a cultural text.

5 Damen (1987, p. 23) reviewing Rich & Owaga, (1982) reports that "the field of intercultural communication has been identified by many names: cross-cultural communication, transcultural communication, interracial communication, international communication, or even contracultural communication."

6 Other authors have proposed a similar approach to culture in EFL teaching that has been defined as "critical cross-cultural literacy" (See Kramsch, 1996).

References

Abdallah-Pretceille, M. (2001). La educación intercultural. Barcelona: Idea Books.

Ariza, D. (2007). Culture in the EFL classroom at Universidad de la Salle: An innovation project. Actualidades Pedagógicas, 50, 9-17.

Badillo, F. (2006). Teachers' conceptions of the target culture. Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas. Unpublished thesis.

Brislin, R. (1993). Understanding culture's influence on behavior. Honolulu: Harcourt Brace College Publishers.

Brown, H. (2000). Principles of language learning and teaching. San Francisco State University: Longman.

Byram, M. (2000). Intercultural communicative competence: The challenge for language teacher training. In N. Mountford & N. Wadham-Smith (Eds.), British Studies: Intercultural Perspectives (pp. 95-102). Edinburgh: Longman in Association with the British Council.

Byram, M., & Risager, K. (1999). Language teachers, politics and cultures. Clevelon: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Byram, M., & Feng, A. (2005). Teaching and researching intercultural competence. In E. Hinkel, (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (pp. 911-930). Seattle: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Campo, E., & Zuluaga, J. (2000). Complimenting: A matter of cultural constraints. Colombian Applied Linguistic, 2(1), 27-41.

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1996a). Fundamentos teóricos de los enfoques comunicativos I. Revista Signos, 17, 56-6.

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1996b). Fundamentos teóricos de los enfoques comunicativos II. Revista Signos, 18, 78-89.

Cortazzi, M., & Jin, L. (1999). Cultural mirrors: Materials and methods in the EFL classroom. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Culture in Second Language Teaching and Learning (pp. 196-220). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cruz, F. (2007). Broadening minds: Exploring intercultural understanding in adult EFL learners. Colombian Applied Linguistic, 9, 144-173.

Damen, L. (1987). Culture learning: The fifth dimension in the language classroom. Boston: Addison Wesley Publishing Company.

De Mejía, A. M. (2006). Bilingual education in Colombia. Towards recognition of languages, cultures and identities. Colombian Applied Linguistic, 8, 152-168.

Eagleton, T. (1983). Literary theory. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Edge, J. (1992). Cooperative development. Harlow: Longman.

Fairclough, N. (1989). Language and power. New York: Longman.

Fairclough, N. (1995). Critical discourse analysis. England: Longman.

Forster, E. M. (2003). A room with a view. London: Penguin.

Foucault, M. (1984). Las palabras y las cosas. Barcelona: Planeta-Agostini.

Fowler, R. (1983). Lenguaje y control. México: Fondo de Cultura económica.

Geertz, C. (1973). La interpretación de las culturas. Barcelona: La Gedisa.

Gladstone, J. R. (1980). Language and culture. In B. Donn, English language teaching perspectives (pp.19-22). London: Longman.

González, O. (1990). Teaching language and culture with authentic materials. Virginia: UMI.

Gudykunst, W., & Ting-Toomey, S. (1988). Culture and interpersonal communication. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Hinkel, E. (1999). Culture in second language teaching and learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hinkel, E. (2005). Identity, culture, and critical pedagogy in second language teaching and learning. In E.Hinkel (Ed), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (pp. 891-893). Seattle: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Holliday, A. (1994). Appropriate methodology and social context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kim, K., Chin, C., & Goodman, Y. (2004). Revaluating the reading process of adult ESL/EFL learners through critical dialogues. calf Special issue on literacy processes, 42-57.

Kramsch, C. (1993). Context and culture in language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kramsch, C. (1996). The cultural component of language teaching. Zeitschrift für Interkulturellen Fremdsprachenunterricht, 1(2), 13 doi: http://www.spz.tu-darmstadt.de/projekt_ejournal/jg_01_2/beitrag/kramsch2.htm

Kramsch, C. (1998). Language and Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kramsch, C. (2001). Intercultural communication. In R. Carter, & D. Nunan (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to teaching English to speakers of other language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kramsch, C. (2002). The privilege of the intercultural speaker. In Byram & Fleming, Language Learning in Intercultural perspective. Approaches through drama and ethnography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lado, R. (1998). How to compare two cultures. In J. Valdés (Ed.), Culture Bound. Brinding the Cultural Gap in Language Teaching (pp. 52-63). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Levine, D., & Aldeman, M. (1982). Beyond language intercultural communication for English as a second language. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Lustig, M., & Koester, J. (1999). Intercultural competence. New York: Addison Wesley Longman.

Mojica, C. (2007). Exploring children's cultural perceptions through tasks based on films in an Afterschool program. Colombian Applied Linguistic, 9, 7-24.

Moran, P. (2001). Teaching culture: perspectives in practice. Ontario: Heinle & Heinle Thompson Learning.

Nunan, D., & Lamb, C. (1996). The self-directed teacher. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nieto, S. (2002). Language culture and teaching: Critical perspectives for a new century. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Paige, R. M., Jorstad, H., Siaya, L., Klein, F., & Colby, J. (2008). Culture learning in language education: A review of the literature. Retrieved on January 9, 2008, from Center for advanced research on language acquisition, Web site: http://www.carla.umn.edu/culture/resources/index.html

Pavlenko, A., & Blackedge, A. (2004). Negotiation of identities in multicultural contexts. London: Florence Production.

Pennycook, A. (2002). Critical applied linguistics. Retrieved on May 8, 2002, from University of Technology Sidney, Web site: http://www.education.uts.edu.au/ostaff/staff/alastair_pennycook.html

Peterson, E., & Coltrane, B. (2003). Culture in second language teaching. Retrieved on December 20, 2007, from CAL Digest, Web site: http://www.cal.org/resources/digest/0309peterson.html

Porto, M. (2000). Integrating the teaching of language and culture. In Mountford & N. Wadham-Smith (Eds.), British Studies: Intercultural Perspectives, (pp. 89-94). Edinburgh: Longman in Association with the British Council.

Posada, J. (2004). Affirming diversity through reading. Colombian Applied Linguistic, 6, 92-105.

Oliveras, A. (2000). Hacia la competencia intercultural en el aprendizaje de una lengua extranjera. Barcelona: Editorial Edinumen.

Ommagio, A. (1986). Teaching language in context. Boston: Heinle & Heinle Publishers.

Quintero, J. (2006). Contextos culturales en el aula de inglés. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 11(17), 151- 177.

Ramírez, L. (2007). Comunicación y discurso. Bogotá: Magisterio.

Real, L. (2007). Developing students' intercultural competence through literature. Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas. Thesis in process.

Ricento, T. (2005). Considerations of identity in L2 learning. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (pp. 895-910). Seattle: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Rowena, F., & Furuto, S. (2001). Culturally competent practice: Skill interventions and evaluations. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Savignon, S. (1997). Communicative competence. Theory and classroom practice. New York: Mc-Graw-Hill.

Stern, H. H. (1983). Fundamental concepts of language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stern. H. (1992). The cultural syllabus. In H. Stern, Issues and Options in Language Teaching (pp. 205-242). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Storey, J. (1993). Cultural theory and popular culture. Georgia: The University of Georgia Press.

Storey, J. (1996). Cultural studies and the study of popular culture: theories and methods. Georgia: University of Georgia Press.

Strinati, D. (1995). Introduction to theories of popular culture. NY: Routledge.

Van Dijk, T. (2000a). El discurso como interacción en la sociedad. In T. Van Dijk (Ed.), El discurso como interacción social (pp. 19-66). Barcelona: Gedisa.

Van Dijk, T. (2000b). El estudio del discurso. En T. Van Dijk (Ed.), El discurso como estructura y proceso (pp. 21-65). Barcelona: Gedisa.

Velásquez, J. (2002). Integrating email projects to English classroom: Looking for intercultural understanding. Colombian Applied Linguistic, 4, 78-84.

About the Authors

José Aldemar Álvarez Valencia holds a Master's in Applied Linguistics to tefl and is a candidate for the Master's in Hispanic Linguistics at Instituto Caro y Cuervo. He is a full time professor in the School of Languages at Universidad de La Salle and works part time at Universidad Nacional de Colombia, in Bogotá. He is an active member of the Board of Directors of the Asociación Colombiana de Profesores de Inglés (asocopi).

Sandra Ximena Bonilla Medina holds a Master's in Applied Linguistics to tefl from Universidad Distrital. She is a full time professor in the School of Languages at Universidad de La Salle and works part time at Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas.

References

Abdallah-Pretceille, M. (2001). La educación intercultural. Barcelona: Idea Books.

Ariza, D. (2007). Culture in the EFL classroom at Universidad de la Salle: An innovation project. Actualidades Pedagógicas, 50, 9-17.

Badillo, F. (2006). Teachers' conceptions of the target culture. Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas. Unpublished thesis.

Brislin, R. (1993). Understanding culture's influence on behavior. Honolulu: Harcourt Brace College Publishers.

Brown, H. (2000). Principles of language learning and teaching. San Francisco State University: Longman.

Byram, M. (2000). Intercultural communicative competence: The challenge for language teacher training. In N. Mountford & N. Wadham-Smith (Eds.), British Studies: Intercultural Perspectives (pp. 95-102). Edinburgh: Longman in Association with the British Council.

Byram, M., & Risager, K. (1999). Language teachers, politics and cultures. Clevelon: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Byram, M., & Feng, A. (2005). Teaching and researching intercultural competence. In E. Hinkel, (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (pp. 911-930). Seattle: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Campo, E., & Zuluaga, J. (2000). Complimenting: A matter of cultural constraints. Colombian Applied Linguistic, 2(1), 27-41.

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1996a). Fundamentos teóricos de los enfoques comunicativos I. Revista Signos, 17, 56-6.

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1996b). Fundamentos teóricos de los enfoques comunicativos II. Revista Signos, 18, 78-89.

Cortazzi, M., & Jin, L. (1999). Cultural mirrors: Materials and methods in the EFL classroom. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Culture in Second Language Teaching and Learning (pp. 196-220). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cruz, F. (2007). Broadening minds: Exploring intercultural understanding in adult EFL learners. Colombian Applied Linguistic, 9, 144-173.

Damen, L. (1987). Culture learning: The fifth dimension in the language classroom. Boston: Addison Wesley Publishing Company.

De Mejía, A. M. (2006). Bilingual education in Colombia. Towards recognition of languages, cultures and identities. Colombian Applied Linguistic, 8, 152-168.

Eagleton, T. (1983). Literary theory. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Edge, J. (1992). Cooperative development. Harlow: Longman.

Fairclough, N. (1989). Language and power. New York: Longman.

Fairclough, N. (1995). Critical discourse analysis. England: Longman.

Forster, E. M. (2003). A room with a view. London: Penguin.

Foucault, M. (1984). Las palabras y las cosas. Barcelona: Planeta-Agostini.

Fowler, R. (1983). Lenguaje y control. México: Fondo de Cultura económica.

Geertz, C. (1973). La interpretación de las culturas. Barcelona: La Gedisa.

Gladstone, J. R. (1980). Language and culture. In B. Donn, English language teaching perspectives (pp.19-22). London: Longman.

González, O. (1990). Teaching language and culture with authentic materials. Virginia: UMI.

Gudykunst, W., & Ting-Toomey, S. (1988). Culture and interpersonal communication. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Hinkel, E. (1999). Culture in second language teaching and learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hinkel, E. (2005). Identity, culture, and critical pedagogy in second language teaching and learning. In E.Hinkel (Ed), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (pp. 891-893). Seattle: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Holliday, A. (1994). Appropriate methodology and social context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kim, K., Chin, C., & Goodman, Y. (2004). Revaluating the reading process of adult ESL/EFL learners through critical dialogues. calf Special issue on literacy processes, 42-57.

Kramsch, C. (1993). Context and culture in language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kramsch, C. (1996). The cultural component of language teaching. Zeitschrift für Interkulturellen Fremdsprachenunterricht, 1(2), 13 doi: http://www.spz.tu-darmstadt.de/projekt_ejournal/jg_01_2/beitrag/kramsch2.htm

Kramsch, C. (1998). Language and Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kramsch, C. (2001). Intercultural communication. In R. Carter, & D. Nunan (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to teaching English to speakers of other language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kramsch, C. (2002). The privilege of the intercultural speaker. In Byram & Fleming, Language Learning in Intercultural perspective. Approaches through drama and ethnography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lado, R. (1998). How to compare two cultures. In J. Valdés (Ed.), Culture Bound. Brinding the Cultural Gap in Language Teaching (pp. 52-63). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Levine, D., & Aldeman, M. (1982). Beyond language intercultural communication for English as a second language. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Lustig, M., & Koester, J. (1999). Intercultural competence. New York: Addison Wesley Longman.

Mojica, C. (2007). Exploring children's cultural perceptions through tasks based on films in an Afterschool program. Colombian Applied Linguistic, 9, 7-24.

Moran, P. (2001). Teaching culture: perspectives in practice. Ontario: Heinle & Heinle Thompson Learning.

Nunan, D., & Lamb, C. (1996). The self-directed teacher. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nieto, S. (2002). Language culture and teaching: Critical perspectives for a new century. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Paige, R. M., Jorstad, H., Siaya, L., Klein, F., & Colby, J. (2008). Culture learning in language education: A review of the literature. Retrieved on January 9, 2008, from Center for advanced research on language acquisition, Web site: http://www.carla.umn.edu/culture/resources/index.html

Pavlenko, A., & Blackedge, A. (2004). Negotiation of identities in multicultural contexts. London: Florence Production.

Pennycook, A. (2002). Critical applied linguistics. Retrieved on May 8, 2002, from University of Technology Sidney, Web site: http://www.education.uts.edu.au/ostaff/staff/alastair_pennycook.html

Peterson, E., & Coltrane, B. (2003). Culture in second language teaching. Retrieved on December 20, 2007, from CAL Digest, Web site: http://www.cal.org/resources/digest/0309peterson.html

Porto, M. (2000). Integrating the teaching of language and culture. In Mountford & N. Wadham-Smith (Eds.), British Studies: Intercultural Perspectives, (pp. 89-94). Edinburgh: Longman in Association with the British Council.

Posada, J. (2004). Affirming diversity through reading. Colombian Applied Linguistic, 6, 92-105.

Oliveras, A. (2000). Hacia la competencia intercultural en el aprendizaje de una lengua extranjera. Barcelona: Editorial Edinumen.

Ommagio, A. (1986). Teaching language in context. Boston: Heinle & Heinle Publishers.

Quintero, J. (2006). Contextos culturales en el aula de inglés. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 11(17), 151- 177.

Ramírez, L. (2007). Comunicación y discurso. Bogotá: Magisterio.

Real, L. (2007). Developing students' intercultural competence through literature. Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas. Thesis in process.

Ricento, T. (2005). Considerations of identity in L2 learning. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (pp. 895-910). Seattle: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Rowena, F., & Furuto, S. (2001). Culturally competent practice: Skill interventions and evaluations. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Savignon, S. (1997). Communicative competence. Theory and classroom practice. New York: Mc-Graw-Hill.

Stern, H. H. (1983). Fundamental concepts of language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stern. H. (1992). The cultural syllabus. In H. Stern, Issues and Options in Language Teaching (pp. 205-242). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Storey, J. (1993). Cultural theory and popular culture. Georgia: The University of Georgia Press.

Storey, J. (1996). Cultural studies and the study of popular culture: theories and methods. Georgia: University of Georgia Press.

Strinati, D. (1995). Introduction to theories of popular culture. NY: Routledge.

Van Dijk, T. (2000a). El discurso como interacción en la sociedad. In T. Van Dijk (Ed.), El discurso como interacción social (pp. 19-66). Barcelona: Gedisa.

Van Dijk, T. (2000b). El estudio del discurso. En T. Van Dijk (Ed.), El discurso como estructura y proceso (pp. 21-65). Barcelona: Gedisa.

Velásquez, J. (2002). Integrating email projects to English classroom: Looking for intercultural understanding. Colombian Applied Linguistic, 4, 78-84.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

Copyright (c) 2009 José Aldemar Álvarez Valencia, Ximena Bonilla Medina

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.