Exploring Knowledge of English Speaking Strategies in 8th and 12th Graders

Exploración del conocimiento de las estrategias de expresión oral en inglés en estudiantes de los grados octavo y duodécimo

Keywords:

Learning English, oral communication, speaking strategies (en)Aprendizaje del inglés, comunicación oral, estrategias de expresión oral (es)

This article presents a research study that analyses eighth and twelfth graders' knowledge of speaking strategies to communicate in English. The Oral Communication Strategy Inventory, developed by Nakatani in 2006, was applied to 108 students belonging to the public, semi-public and private educational sectors in Chile. The findings show that 8th graders claim to have broader knowledge of speaking strategies than 12th year secondary students, and the knowledge of speaking strategies of elementary and secondary school students does not vary depending on the type of school: public, semi public and/or private.

En este artículo se presenta una investigación en la que se analiza el conocimiento que estudiantes de octavo básico y primero medio declaran tener cuando se comunican en inglés. Se aplicó el Inventario de comunicación oral, propuesto por Nakatani (2006), a ciento ocho estudiantes que pertenecen a sectores educativos públicos, particulares-subvencionados y privados en Chile. Los resultados muestran que los estudiantes de octavo básico declaran tener mayor conocimiento de las estrategias de expresión oral que los estudiantes de grado doce, y el conocimiento de dichas estrategias no varía según el tipo de sector educativo al que pertenecen.

Exploring Knowledge of English Speaking

Strategies in 8th and 12th Graders*

Exploración del conocimiento de las estrategias de expresión oral en inglés

en estudiantes de los grados octavo y doceavo

Claudio Díaz Larenas

Universidad de Concepción, Chile

claudiodiaz@udec.cl

This article was received on January 20, 2011, and accepted on April 17, 2011.

This article presents a research study that analyses eighth and twelfth graders' knowledge of speaking strategies to communicate in English. The Oral Communication Strategy Inventory, developed by Nakatani in 2006, was applied to 108 students belonging to the public, semi-public and private educational sectors in Chile. The findings show that 8th graders claim to have broader knowledge of speaking strategies than 12th year secondary students, and the knowledge of speaking strategies of elementary and secondary school students does not vary depending on the type of school: public, semi public and/or private.

Key words: Learning English, oral communication, speaking strategies.

En este artículo se presenta una investigación en la que se analiza el conocimiento que estudiantes de octavo básico y primero medio declaran tener cuando se comunican en inglés. Se aplicó el Inventario de comunicación oral, propuesto por Nakatani (2006), a ciento ocho estudiantes que pertenecen a sectores educativos públicos, particulares-subvencionados y privados en Chile. Los resultados muestran que los estudiantes de octavo básico declaran tener mayor conocimiento de las estrategias de expresión oral que los estudiantes de grado doce, y el conocimiento de dichas estrategias no varía según el tipo de sector educativo al que pertenecen.

Palabras clave: aprendizaje del inglés, comunicación oral, estrategias expresión oral.

Introduction

Learning a language is a complex issue that requires the participation of at least three main stakeholders: teachers, students and contents. Therefore, there is a didactic triangle that should allow students to construct their own knowledge, a process that is not always easy to grasp and produce autonomously. For this reason, the concept of strategy is fundamental as a group of operations, steps and devices that the learner can use to acquire and store knowledge. The importance of knowing and using speaking strategies is to help students improve their language development in order to encourage effective spoken communication. In this matter, teachers should act as facilitators who teach these strategies that can help students to develop their language skills. Some of these oral strategies might be related to negotiation of meaning or the alteration of the message. Some others may be connected with body language or even with the abandonment of the message that is being produced. In brief, this particular study focuses on the speaking strategies declared to be used by 8th and 12th graders in order to achieve oral communication in English.

Theoretical Framework

Chilean society today requires that secondary school students improve their language proficiency level, so that they can be active participants in this globalized world. In this context, the purpose of teaching English as a foreign language via Chilean public, semi-public and private education is to give students a linguistic tool that can enable them to understand and communicate information, knowledge and technologies as well as to appreciate other cultures, traditions and ways of thinking (Crookes, 2003).

Communicative language teaching is the trend in the teaching of English as a foreign language, embraced by the Chilean English Policy. As such, the main aim of communicative language teaching is to help students develop their ability to communicate in the target language. This endeavor suggests that students should be able to communicate in English using different language functions and notions. They must manage meaning and a range of linguistic components, since communication is seen as a process of negotiating meaning among the participants of the communicative situation. The emphasis is on students' ability to maintain a conversation rather than master a set of lexical or grammatical components (Brown, 2001; Brown, 2007; Richards, 2005).

In communicative language teaching, the teacher is expected to act as a facilitator of the communicative situation, monitoring students' attempts to communicate in the target language. The correction of errors or the use of the teacher as a model of perfect speech is left behind as the focus is to promote students' participation and motivate them to produce speech in the target language. The active participation of the students is essential. Students should be engaged and willing to practice producing speech and negotiating meaning to create a communicative situation. As the main focus is for students to be able to communicate in the target language, learners need to work cooperatively, in pairs or in groups as interaction gives them the ability to create meaning and therefore communication (Larsen-Freeman, 2000). The learners are seen as responsible for their own learning since they need to try to understand each other and make themselves understood. (Richards, 2005; Thornbury, 2005).

Speaking and Listening in English

Describing oral production leads to oral communication and both of them can be defined as any type of interaction that makes use of spoken words, an interaction that is really important and essential nowadays. It has also been printed out that the ability to communicate effectively through speaking as well as in writing is highly valued, and in demand (Johnson, 2001). One of the major concerns when teaching a foreign language is how to prepare learners to be able to use the language. Therefore, for teachers to make a lesson successful, they must clearly present the aims of the lesson. When teaching the students how to speak, for example, it is necessary for them to have some knowledge of the language conventions such as grammar, vocabulary and pronunciation. It is important, therefore, to allow learners to practice speaking as an opportunity to use the grammar, pronunciation and vocabulary previously taught and, of course, the most essential task is the practice of the oral skill (Bygate, 1987).

When talking about oral skills, it can be said that there are two different ways in which these skills can be divided. The first division is the motor-perceptive skills, which involve perceiving, recalling and articulating the correct order of sounds and structures of the target language. The second division is the interaction skills, which involve making decisions about communication and the ability to use language in order to satisfy particular demands, not structure (Buck, 2001; Osada, 2004). In oral production there is something imperative that every single speaker faces when speaking: time pressure. Time pressure affects the target language because it makes the speaker think about devices to facilitate and compensate her/his oral production. As a consequence of this situation, there are four features presented in spoken language: "(A) It is easier to improve if the speakers use less complex syntax; (B) speakers tend to abbreviate and produce incomplete sentences; (C) it is easier to produce messages if speakers use fixed phrases; (D) speakers will use devices to gain time while speaking" (Bygate, 1987, p. 14).

To make the previous observations clearer it is necessary to explain two different ideas about oral production: facilitation and compensation. The first one is related to the ways in which a speaker can facilitate his or her speech. There are four ways to facilitate speech production: "(A) By simplifying structures. (B) By ellipsis, this is the omission of parts of a sentence. (C) By using formulaic expressions, these are the well-known colloquial or idiomatic expressions. (D) By the use of fillers and hesitation devices, these tend to give more time to the speaker to formulate what he/she wants to say" (Bygate, 1987, p. 15).

Compensation, the second idea, is related to modifying what the speaker has already said. It is an alteration in the speech, which is permitted among speakers. There are also four ways to have this done: "(A) By adjustments, such as hesitation, false start, self-correction, rephrasing and circumlocutions. (B) By syntactic features, such as ellipsis and parataxis. (C) By repetition, via expansion or reduction of the speech. (D) By using formulaic expressions, these are the well-known colloquial or idiomatic expressions" (Bygate, 1987, p. 20).

All these features must be taken into consideration by both learners and teachers. In relation to learners, it is better to make clear messages using short sentences, and the appropriate vocabulary. In order to develop a range of more complex ways of extending sentences, learners need to become skilled in producing utterances so that they can achieve fluency. For teachers, it is necessary to be aware of the opportunities that learners are offered for improving their skills. It is also essential for teachers to know how oral production should be taught. Then there are three important aims that must be achieved: (A) Methodology of teaching oral skills, (B) Assessment of some actual examples of oral material and (C) Language of learners working on such activities.

The Process of Interaction in Oral Communication

To understand oral communication, the interaction of two different participants is needed: the speaker and the listener. It has to be stated that listening comprehension is fundamental in speaking and that the two skills must be used simultaneously. However, the time and space to process speaking and listening are very limited; indeed, when the utterance is produced, it lasts just the moment of speaking.

Through the years, "listening comprehension as a skill, has been underestimated, since teachers used to think that it was something students could learn on their own without being taught how to do it. In the early twenties, teachers tended to leave out the teaching of the listening skill from their planning mostly because they thought it should be something learnt by osmosis" (Osada, 2004, p. 54). In this matter, it was thought that the more the students listened to English, the more they learnt, without any help. Therefore, their role was mainly to listen to the teacher when drilling and imitating dialogues. It is well-known that "speaking itself does not constitute communication unless what is being said is comprehended by another person" (Muchmore, 2004, p. 34), so when teaching speaking in any language, L1 or L2, the aim is communication and to achieve this, the two participants need to understand the meaning of the messages that are being sent. However, it was not until the 70s that the status of listening began to change from a secondary skill into something of central importance (Celce-Murcia, 2001; Harmer, 2001; Mckay, 2003; Osada, 2004). Educators became aware not only of how important comprehension of a foreign language was, but also of how complex the achievement of listening as a skill was and its importance when talking about the comprehension of spoken messages.

To establish a connection between listening and speaking, Buck (2001) states that there are four features in speaking that help to understand the importance of listening comprehension as a skill: (A) Speech is encoded in the form of sounds. (B) It is linear, which means that one idea follows the other one. (C) It takes place in real time with little time to review what has been said. (D) It is linguistically different from written language.

The Concept of Strategy

The definition of strategy has several interpretations, but all of them come from the same source. The word comes from the ancient Greek term 'strategia', used to refer to the tactics employed to defeat the enemy. In the educational field, the use of this term is not very different, but in this case the enemy is the students' lack of knowledge. Oxford (1992, p. 15) offers the following definition: strategies are specific actions, behaviours, steps or techniques that students (often intentionally) use to improve their progress in developing L2 skills. These strategies can facilitate the internalization, storage, retrieval or use of the new language. Strategies are tools for the self-directed involvement necessary for developing communicative ability.

Based on Oxford (1992), direct strategies for dealing with the new language are the first major classification and are used to work with the language in different tasks and situations. The second major classification is indirect strategies used for the general acquisition of learning. When conditions are created for the students' development of strategies, teachers need to bear in mind that what they teach must be consistent with what students need. According to Hedge (2000) and Macaro (2003), it is possible to identify four needs: (A) Contextualised practise: the aim is to connect the linguistic features with their functions by finding a situation in which what they are learning is commonly used. (B) Personalised language: the teacher has to make students express their ideas, feelings and opinions using the target language. Students tend to remember more of the language when they can use it in interpersonal situations. (C) Building awareness of the social use of the language: the aim here is to make students understand that there are situations with an appropriate social behaviour and an appropriate use of the language. Therefore, conversational misunderstandings that can cause language problems can be avoided. (D) Building confidence: when teachers build confidence in students they are able to produce the language quickly and automatically at ease. Teachers also need to create a positive environment for classroom communication.

In brief, the teaching context in this 21st century is determined by the globalised world in which students are immersed. The demanding work conditions create a need for students to be autonomous and efficient in all areas. It is in this context where learning strategies become important to develop the students' language ability in order for them to be self-sufficient and direct their own learning process.

Research Methodology

This section contains the research framework that has guided this study. The general objective was to identify the speaking strategies that 8th and 12th graders from public, semi-public and private schools claim to use when speaking English. By the same token, the following were the hypotheses:

• 12th graders will show broader knowledge of speaking strategies than 8th graders.

• The knowledge of speaking strategies will vary depending on the type of school: public, semi-public and private.

As far as the definition of variables, these are presented as follows:

Speaking strategies: They are actions and/or procedures that students apply in order to complete an oral communicative task successfully.

Types of school: Within the national educational system, there are three types of schools: public, semi-public and private.

Year group: 8th graders: Group of students whose ages range from 13 to 14 and 12th graders: Group of students whose ages range from 17 to 18.

Type of Research Design

This is a non-experimental and correlational study (Hernández, Fernández & Baptista, 1996). Non-experimental research is a systematic and empiric research where independent variables are not manipulated due to the fact that they have already been used. The inferences about the associations among variables are to be made without any intervention or direct influence, and they can be observed as they were given in their natural context (Aliaga & Gunderson, 2002; Cresswell, 2003; Murray, 2003).

Subjects

The subjects included for data collection purposes are fifty-four 8th year elementary school students coming from three types of schools: public, semi-public and private.

Instrument

The instrument is a validated inventory called Oral Communication Strategy Inventory - OCSI (See Appendix). It was specifically designed for investigating the use of oral communicative strategies, particularly to determine the strategies used for coping with speaking and listening problems. Oxford (1996) claimed that "questionnaires are among the most efficient and comprehensive ways to assess the frequency of language learning strategy use". The inventory has been taken from the article "Developing an Oral Communication Strategy Inventory" by Nakatani (2006), who gave his permission to validate it and translate it into Spanish so that students would not have problems understanding the inventory statements. The inventory was validated by five native English speakers and five Chilean academics in order to avoid alterations and misconceptions of any kind.

The inventory consists of fifty-two statements divided into two sections: Strategies for coping with speaking problems and strategies for coping with listening problems. Its aim is to assess the knowledge of speaking strategies while communicating. Nakatani (2006) groups speaking strategies into seven different types which are described as follows:

- Strategy type 1: Fuency-oriented strategy; this strategy is seen when students pay attention to aspects like rhythm, intonation, pronunciation and speech clarity in order to improve listeners' attention.

- Strategy type 2: Negotiation for meaning while speaking; this strategy is related to the speaker's attempts to negotiate with the listener. To keep and maintain their interaction and avoid breakdowns while communicating, they both modified the message by giving examples and repeating the speech to figure out what they really wanted to say.

- Strategy type 3: Accuracy-oriented strategy; it is associated with the desire to speak English with some accuracy. Learners pay attention to the form of their speech and look for grammatical accuracy; therefore, they correct what they are saying by noticing their own mistakes.

- Strategy type 4: Message reduction and alteration strategy; it is closely connected with the reduction and simplification of the message by using similar expressions in order to avoid breakdowns.

- Strategy type 5: Non-verbal strategy while speaking; this strategy is directly linked to the use of body language. Learners use eye contact, gestures and facial expressions to achieve communication.

- Strategy type 6: Message abandonment strategy; it is associated with the abandonment of the message in ESL communication. Learners have a tendency to give up their endeavour to communicate when they face difficulties carrying out their message.

- Strategy type 7: Attempt to think in English strategy; this strategy is useful for learners who think in the second language during their speech. Learners tend to think in English and avoid thinking in their native language.

Procedure

The information was gathered using the closed-question inventory (Oral Communication Strategy Inventory - OCSI) that had already been applied in order to conduct a research project on oral communication strategies in Japan. To corroborate that the instrument could be used in a Chilean context, specifically with teenagers, it was tested and piloted on 6 teenagers outside of the sample population in November, 2009. Students responded to the inventory during class time taking twenty minutes to fill it in. During the administration, students could ask the inventory administrator questions about issues they did not fully understand.

Data analysis

As mentioned before, in order to collect the data, a speaking strategy inventory was applied and answered by 108 Chilean students from three different school contexts. The inventory statements were arranged in a Likert scale format in which students might report the frequency with which they used strategies in oral communication. The statements were expected to be answered using a scale ranging from 1 to 5: 1 being never true of me; 2, almost never true of me; 3, sometimes true of me; 4, almost always true of me and 5, always true of me.

The responses were added and then divided by the number of statements giving a final average which was analysed by Statgraphics Centurion, which is a statistical software program for exploratory data analysis and statistical modelling. This software program allows researchers, through statistical procedures, to make deep analyses of data to manage and analyse statistic values. The discussion will be conducted based on the two research hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1: The Knowledge of Speaking Strategies Will Vary Depending on the Type of School: Public, Semi-Public and Private

After analysing the data through the Stat-graphics Centurion program, a variance analysis, which is a statistical procedure to verify and measure the data, was conducted and the final results obtained. The data analysis of each subject reflects the following results which are organised according to the two variables presented in Table 1.

As shown in Table 1, it has been observed that there is no statistically meaningful effect of the type of school variable since its value is higher than 0.05, the rank for accepting or declining the hypothesis. This means that among the public, semi-public and private schools that were analysed in this research, there is no difference in the students' knowledge of speaking strategies. In other words, the three school realities do not necessarily lead to stronger or weaker alleged knowledge of speaking strategies.

| P-value | |

| Main variables | |

| A: Type of school (public, semi-public and private) | 0.2043 |

| B: Year group (8th and 12th graders) | 0.0147 |

| Interaction of both features (A and B) | 0.2043 |

Thus, the hypothesis that states that the claimed knowledge of speaking strategies in elementary and secondary school students will vary, depending on the type of school and given the results obtained, is declined. This observation implies that private school students do not necessarily show broader speaking strategy knowledge than those students from the public and semi-public school sectors, as might be expected. As Thornbury (2005) states, a shortage of opportunities for practice is identified as an important contributing factor to students' lack of speaking strategies. The fact that this hypothesis is declined may be due to several reasons that constitute an attempt to explain this hypothesis declination, namely:

-

Regardless of the school reality, the one hundred and eight subjects are taught by local Chilean teachers of English who received the same undergraduate education during their university years. The teachers' ages reveal that when they were doing their university studies, the concept of strategy was not fully developed among educators; therefore, the strategy issue today might be a little puzzling for them.

-

Speaking has always been regarded as a difficult language skill to teach and to learn. What is more, Chilean secondary school teachers tend to focus their attention on developing reading and listening skills, as stated in the National Language Syllabus.

-

The explicit teaching of strategies does not seem to be taught in any of the school realities.

-

Speaking activities probably take longer to be taught and assessed; that is why teachers avoid doing them with their students. The process may be complicated by a tendency to formulate the utterance first in the mother tongue and then 'translate' it into the foreign language, with an obvious cost in terms of speed (Luoma, 2004).

-

Secondary school students tend to focus on subjects of their curriculum that they regard as important for their professional future. English does not seem to be one of these subjects.

Hypothesis 2: 12th Graders Will Show Broader Knowledge of Speaking Strategies than 8th Graders

Since the p-value for the year group variable is below 0.05, this shows a statistically meaningful effect of the data analysis. Then, the hypothesis that states that 12th graders show broader knowledge of speaking strategies than 8th year elementary students is also declined. Contrary to what was expected, 8th graders show higher claimed knowledge of speaking strategies than 12th year secondary school students, regardless of the type of school. To clarify this issue further, a test that uses the statistical rank of data points (multiple ranks test) was applied and is presented in Table 2, which shows that the average for 8th graders is higher than the one for 12th graders.

The difference between both grades is 0.29 as it can be seen in Table 3. This implies a meaningful difference between 8th and 12th year students' alleged knowledge of speaking strategies. Since 8th graders claim to have broader speaking strategy knowledge than 12th graders, it is important to find out which types of speaking strategies are mostly used by the 8th grade group, ranked below from the most to the least used strategy.

Table 2. Multiple Ranks Test Analysis of the Year Group Variable

| Grade | Subjects | Average |

|---|---|---|

| 12th graders | 54 | 3.25926 |

| 8th graders | 54 | 3.55556 |

Table 3. Multiple Ranks Test Analysis of the Strategy Type by 8th Year Elementary Students

| Average | |

| Strategy type 2: Negotiation for meaning while speaking | 3.96296 |

| Strategy type 1: Fluency-oriented strategy | 3.77778 |

| Strategy type 5: Non-verbal strategy while speaking | 3.75926 |

| Strategy type 7: Attempt to think in English strategy | 3.75926 |

| Strategy type 4: Message reduction and alteration strategy | 3.62963 |

| Strategy type 3: Accuracy-oriented strategy | 3.55556 |

| Strategy type 6: Message abandonment strategy | 3.03704 |

As shown in Table 3, it is observed that the most common strategy claimed to be known by the students is strategy type 2, referring to negotiation for meaning while speaking. Learners claim to negotiate with the listener to keep and maintain interaction to avoid breakdowns. The second most claimed strategy to be known is strategy type 1, named as fluency-oriented strategy. Learners claimed to pay attention to the rhythm, intonation and pronunciation to improve their speech and avoid misunderstandings while communicating. Thornbury (2005) states

If speaking as a skill is dealt with, it is often dealt with only at the level of pronunciation. Frequently, training and practice in the skill of interactive real-time talk, with all its attendant discourse features, is relegated to the chat stage at the beginning and end of lessons (p. 28).

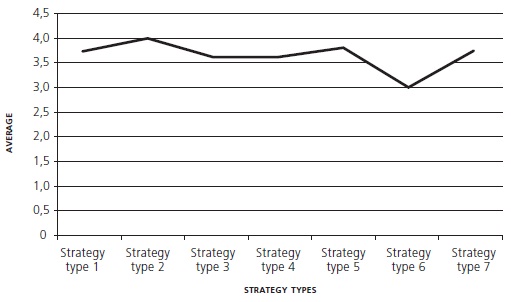

Figure 1 highlights the most common strategies claimed to be known by 8th grade elementary school students.

Figure 1. Strategy Types for 8th Year Elementary

School Students

Eighth graders might present a higher development of social skills, based on what the subjects claim; they are more willing to communicate using body language and paying attention to the interlocutor's reaction toward the message. Students tend to do that in order to avoid breakdowns and keep the conversation flow smooth. One set of features having an influence on what gets said in a speech event and how it is said is the social and situational context in which the talk happens (Luoma, 2004). Students are not afraid of explaining terms or giving examples so that they can clarify the meaning of the message. Moreover, it can also be concluded that 8th graders, due to their age, are willing to communicate and eager to take risks in communicative situations.

Twelfth graders, on the other hand, reveal interesting data regarding speaking strategy knowledge. As seen in Table 4, there is also a difference in the knowledge of 12th graders' strategies. Again, they are organized from the most common to the least frequent strategy.

Table 4. Multiple Ranks Test Analysis of the

Strategy Type Used by 12th Year Secondary Students

| Average | |

| Strategy type 5: Non-verbal strategy while speaking | 3.98148 |

| Strategy type 2: Negotiation for meaning while speaking | 3.59259 |

| Strategy type 1: Fluency-oriented strategy | 3.44444 |

| Strategy type 4: Message reduction and alteration strategy | 3.31481 |

| Strategy type 7: Attempt to think in English strategy | 3.12963 |

| Strategy type 3: Accuracy-oriented strategy | 3.03704 |

| Strategy type 6: Message abandonment strategy | 2.98148 |

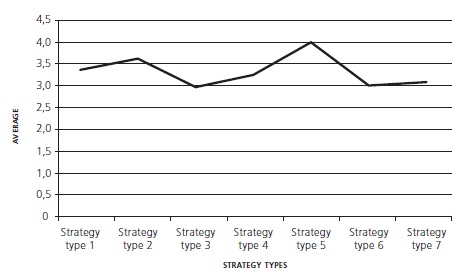

The most common strategy in the 12th grade group is related to strategy type 5, named as nonverbal strategy while speaking. Strategy type 5 has a statistically meaningful effect on the data analysed, with a 95% confidence level. The results show that this strategy is directly linked to the use of body language and learners' use of eye contact, gestures and facial expressions to achieve and succeed while communicating. The second most common strategy refers to negotiation for meaning while speaking, which appears to be the same second most common strategy among 8th graders. Figure 2 highlights the most common strategies claimed to be known by 12th grade elementary school students.

Figure 2. Analysis of Strategy Types by 12th Graders

Thornbury (2005) states that when students are learning a language, most of the time they lack confidence, so, in order to avoid embarrassment they might tend to use body language to express what they want to say. They might prefer to look or appear confident rather than ignorant in a foreign language. Hedge (2000) affirms that teachers need to build confidence in their students so they will be able to achieve and produce the language automatically. Besides, this will help them to create a positive environment for classroom communication.

Another reason for 12th graders choice of strategy 5 as the most common might be that nonverbal communication is a kind of language among the Chilean culture, so everybody understands the use of gestures to explain what is being said. A third reason might be that non-verbal communication contributes to keep the flow of a conversation going (Luoma, 2004). Hedge (2000) also points out that one of the things a conversation implies is that the topic must follow smoothly; therefore, it is thought that students might use this strategy to make the conversation pleasant.

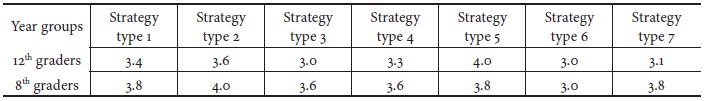

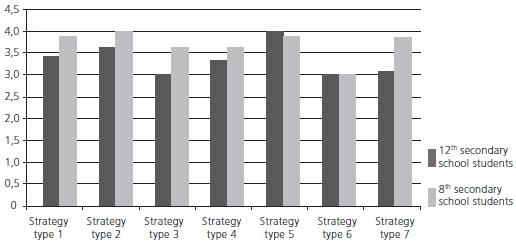

Using the multiple ranks test to identify the contrasting difference between both year groups, a comparative analysis is presented in Table 5.

Table 5. Multiple ranks test analysis of

the strategy types for 8th and 12th graders

As shown in Table 5, strategy types 1, 2, 3, 4, and 7 for 8th graders score higher than those types for 12th graders. Strategy type 2 stands out in the 8th year group, while strategy type 5 stands out in the 12th year group. Strategy type 6 scores the same in both groups. Comparative Figure 3 contrasts both year groups' knowledge of speaking strategies and allows one to conclude that 8th year elementary students seem to have broader knowledge of speaking strategies than 12th year secondary students, based on what the subjects claim.

Figure 3. Comparative Analysis of Strategy Types

Conclusions

Chilean English Language Policy does not stress oral production as a main skill in the official plans and programs; on the contrary, the Language Curriculum emphasises the development of reading and listening, leaving speaking and writing as secondary skills, at least from the perspective of teachers. As teachers of English try to fill in this 'speaking gap' in the curriculum, it is an important task for them to try and find out what speaking strategies are known by students. In this sense, conducting a needs analysis could possibly be a way in which teachers can find out more about the speaking needs of their students. It is always helpful to find out about students' motivation, their prior learning experiences, the situations they are likely to use English in and which skills/language items they need extra practice with.

The conclusions show that there was no difference among the types of school in terms of their claimed speaking strategy knowledge. This could be explained because the Chilean English teachers who teach the subjects of this research share a similar academic formation that leads to the assumption that the methodology and strategies used and not used inside the classroom might be similar. In this respect, the explicit teaching of oral strategies might not be a common practice among the subjects.

It could also have been assumed that secondary school students would use more speaking strategies since they have had more time to expand their language competence. It seems obvious that the longer you spend learning a language, the better at it one becomes. However, after analysing the data from the inventory, it surprisingly appeared that 8th graders claim to know more about speaking strategies than 12th graders while communicating in English. One reason that might explain this is that 8th graders seem to be more motivated towards language learning; therefore, they are more willing to orally communicate and express their thoughts, feelings and opinions in English. Another possible reason is that Chilean 12th graders focus their attention on courses that for them would facilitate their continuity in higher education. They are actually aiming at passing the university entrance exam that would allow them to study the profession they like best. English is not a subject matter that is assessed in the university entrance exam.

Finally, it might be concluded that the importance of knowing speaking strategies can be regarded as a significant issue for improving students' oral communication skill. Therefore, teachers should take the responsibility of promoting the acknowledgment of speaking strategies in oral communication, reinforcing oral tasks and classroom oral interaction. Furthermore, the Chilean Language Policy that intends to foster oral communicative skills among students would not be completely successful if speaking was not directly emphasised and reinforced inside the classroom. It is here where the explicit teaching of speaking strategies as well as the exposure of students to activities that aim at practicing and developing oral communication are crucial issues.

* This paper contains results of the research grant entitled FONDECYT 1085313 "El Sistema de Cognición Docente, las Actuaciones Pedagógicas del Profesor de Inglés Universitario y su Impacto en la Enseñanza-Aprendizaje del Idioma": http://www.fondecyt.cl/578/article-28062.html. The study was conducted between 2008 and 2010.

References

Aliaga, M. & Gunderson, B. (2002). Interactive statistics. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Brown, D. (2007). Teaching by principles. New York, NY: Pearson Education, Inc.

Brown, D. (2001). Principles of language learning teaching. New York, NY: Longman.

Buck, G. (1992). Listening comprehension: Construct validity and trait characteristics. Language Learning, 42(3), 313-357.

Bygate, M. (1987). Speaking: A scheme for teacher education. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Celce-Murcia, M. (2001). Teaching English as a second or foreign language. Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Creswell, J. (2003). Research design. Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods and approaches. London: Sage Publications.

Crookes, G. (2003). A practicum in TESOL. Professional development through teaching practice. Cambridge: Cambridge Language Education.

Harmer, J. (2001). The practice of English language. London: Longman.

Hedge, T. (2000). Teaching and learning in the language classroom. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Hernández, S., Fernández, C., & Baptista, P. (1996). Metodología de la investigación. Ciudad de México: McGraw-Hill Interamenricana de México.

Johnson, K. (2001). An introduction to foreign language learning and teaching. England: Pearson.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2000). Techniques and principles in language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Luoma, S. (2004). Assessing speaking. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Macaro, E. (2003). Teaching and learning a second language: A guide to recent research and its applications. New York, NY: Continuum.

Mckay, S. (2003). Teaching English as a foreign language: The Chilean context. ELT Journal, 57(2), 139-148.

Muchmore, J. (2004). A teacher's life. San Francisco: Backalong Books.

Murray, R. (2003). Blending qualitative and quantitative research methods in theses and Dissertations. California: Corwin Press, Inc.

Nakatani, Y. (2006). Developing an oral communication strategy inventory. The Modern Language Journal, 90(2), 151-168. Retrieved from www.fltrp.com/download/07062706.pdf.

Osada, N. (2004). Listening comprehension research: A brief review of the past thirty years. Dialogue, 3, 53-66. Retrieved from www.talk-waseda.net/dialogue/no03_2004/2004dialogue03_k4.pdf.

Oxford, R. (1996). Employing a questionnaire to assess the use of language learning strategies. Applied Language Learning, 7, 25-45.

Oxford, R. (1992). Language learning strategies: What every teacher should know. Boston: Heinle & Heinle Publishers.

Richards, J. (2005). Communicative language teaching today. Retrieved from www.cambridge.com.mx/site/EXTRAS/jack-cd.pdf.

Thornbury, S. (2005). How to teach speaking. Edinburgh: Pearson Education Limited.

About the Author

Claudio Díaz Larenas holds a PhD in Education and Master of Arts in Linguistics. He teaches English language, discourse analysis and EFL methodology and assessment at Universidad de Concepción. He has also researched in the field of teacher cognition and language assessment.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements are due to the following practitioners for their hard work in this research: Óscar Campos Rodríguez, Patricia Neira Fierro, Carolina Ramos Fuentes, Angela Retamal Vera and Carolina Rojas Cruz.

Appendix: Oral Communication Strategy Inventory (OCSI)

(Based on Nakatani, 2006)

Please read the following items. Choose a response and write it in the space after each item.

- Never or almost never true of me

- Generally not true of me

- Somewhat true of me

- Generally true of me

- Always or almost true of me

Strategies for coping with speaking problems

- I think first of what I want to say in my native language and then construct the English sentence.

- I think first of a sentence I already know in English and then try to change it to fit the situation.

- I use words which are familiar to me.

- I reduce the message and use simple expressions.

- I replace the original message with another message because of feeling incapable of executing my original intent.

- I abandon the execution of a verbal plan and just say some words when I don't know what to say.

- I pay attention to grammar and word order during conversation.

- I try to emphasize the subject and verb of the sentence.

- I change my way of saying things according to the context.

- I take my time to express what I want to say.

- I pay attention to my pronunciation.

- I try to speak clearly and loudly to make myself heard.

- I pay attention to my rhythm and intonation.

- I pay attention to the flow of conversation.

- I try to make eye contact when I am talking.

- I use gestures and facial expressions if I can't communicate how to express myself.

- I correct myself when I notice that I have made a mistake.

- I notice myself using an expression which fits a rule that I have learned.

- While speaking, I pay attention to the listener's reaction to my speech.

- I give examples if the listener doesn't understand what I am saying.

- I repeat what I want to say until the listener understands.

- I make comprehension checks to ensure the listener understands what I want to say.

- I try to use fillers when I cannot think of what to say.

- I leave a message unfinished because of some language difficulty.

- I try to make a good impression on the listener.

- I don't mind taking risks even though I might make mistakes.

- I try to enjoy the conversation.

- I try to relax when I feel anxious.

- I actively encourage myself to express what I want to say.

- I try to talk like a native speaker.

Strategies for coping with listening problems

- I pay attention to the first word to judge whether it is an interrogative sentence or not.

- I try to catch every word that the speaker uses.

- I guess the speaker's intention by picking up familiar words.

- I pay attention to the words which the speaker slows down or emphasizes.

- I pay attention to the first part of the sentence and guess the speaker's intention.

- I try to respond to the speaker even when I don't understand him/her perfectly.

- I guess the speaker's intention based on what he/she has said so far.

- I don't mind if I can't understand every single detail.

- I anticipate what the speaker is going to say based on the context.

- I ask the speaker to give an example when I am not sure what he/she said.

- I try to translate into native language little by little to understand what the speaker has said.

- I try to catch the speaker's main point.

- I pay attention to the speaker's rhythm and intonation.

- I send continuation signals to show my understanding in order to avoid communication gaps.

- I use circumlocution to react the speaker's utterance when I don't understand his/her intention well.

- I pay attention to the speaker's pronunciation.

- I use gestures when I have difficulties understanding.

- I pay attention to the speaker's eye contact, facial expression and gestures.

- I ask the speaker to slow down when I can't understand what s/he has said.

- 20.I ask the speaker to use easy words when I have difficulties comprehending.

- I make a clarification request when I am not sure what the speaker has said.

- I ask for repetition when I can't understand what the speaker has said.

- I make it clear to the speaker that I haven't been able to understand.

- I only focus on familiar expressions.

- I especially pay attention to the interrogative when I listen to WH-questions.

- I pay attention to the subject and verb of the sentence when listening.

References

Aliaga, M. & Gunderson, B. (2002). Interactive statistics. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Brown, D. (2007). Teaching by principles. New York, NY: Pearson Education, Inc.

Brown, D. (2001). Principles of language learning teaching. New York, NY: Longman.

Buck, G. (1992). Listening comprehension: Construct validity and trait characteristics. Language Learning, 42(3), 313-357.

Bygate, M. (1987). Speaking: A scheme for teacher education. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Celce-Murcia, M. (2001). Teaching English as a second or foreign language. Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Creswell, J. (2003). Research design. Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods and approaches. London: Sage Publications.

Crookes, G. (2003). A practicum in TESOL. Professional development through teaching practice. Cambridge: Cambridge Language Education.

Harmer, J. (2001). The practice of English language. London: Longman.

Hedge, T. (2000). Teaching and learning in the language classroom. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Hernández, S., Fernández, C., & Baptista, P. (1996). Metodología de la investigación. Ciudad de México: McGraw-Hill Interamenricana de México.

Johnson, K. (2001). An introduction to foreign language learning and teaching. England: Pearson.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2000). Techniques and principles in language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Luoma, S. (2004). Assessing speaking. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Macaro, E. (2003). Teaching and learning a second language: A guide to recent research and its applications. New York, NY: Continuum.

Mckay, S. (2003). Teaching English as a foreign language: The Chilean context. ELT Journal, 57(2), 139-148.

Muchmore, J. (2004). A teacher's life. San Francisco: Backalong Books.

Murray, R. (2003). Blending qualitative and quantitative research methods in theses and Dissertations. California: Corwin Press, Inc.

Nakatani, Y. (2006). Developing an oral communication strategy inventory. The Modern Language Journal, 90(2), 151-168. Retrieved from www.fltrp.com/download/07062706.pdf

Osada, N. (2004). Listening comprehension research: A brief review of the past thirty years. Dialogue, 3, 53-66. Retrieved from www.talk-waseda.net/dialogue/no03_2004/2004dialogue03_k4.pdf

Oxford, R. (1996). Employing a questionnaire to assess the use of language learning strategies. Applied Language Learning, 7, 25-45.

Oxford, R. (1992). Language learning strategies: What every teacher should know. Boston: Heinle & Heinle Publishers.

Richards, J. (2005). Communicative language teaching today. Retrieved from www.cambridge.com.mx/site/EXTRAS/jack-cd.pdf

Thornbury, S. (2005). How to teach speaking. Edinburgh: Pearson Education Limited.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

Copyright (c) 2011 Claudio Díaz Larenas

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.