Hybrid Identity in Academic Writing: “Are There Two of Me?”

Identidad híbrida: “¿hay dos yo?”

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v16n2.40192Keywords:

Academic writing, attachment, detachment, hybrid, identity (en)Conexión, desconexión, escritura académica, híbrido, identidad (es)

This paper explores the construction of identity in an academic learning environment in Central Mexico, and shows how identity may be linked to non-language factors such as emotions or family. These issues are associated with elements of hybrid identity. To analyze this we draw on language choice as a tool used for the construction of identity and for showcasing and defending identity through exploratory interviews with the bilingual students and teachers. The results draw our attention towards the role of non-linguistic variables and their relationship to emotional and contextual issues that influence how academic writing occurs within the school confines, where hybrid identities may be constructed for academic purposes.

Este artículo explora la construcción de identidad en un medio de aprendizaje en el centro de México y muestra cómo la identidad puede estar relacionada con factores no lingüísticos, como las emociones o la familia. Estos factores están asociados con aspectos de identidad híbrida. Para analizar esto, nos basamos en la elección de lengua del usuario como una herramienta para la construcción de la identidad y para ilustrar y defender la identidad en entrevistas a fondo con alumnos y maestros bilingües. Los resultados atraen nuestra atención hacia el papel de variables no lingüísticas y su relación con factores emocionales y contextuales que influyen en la manera como ocurre la redacción en segunda lengua en la escuela, en donde las identidades híbridas pueden ser construidas para propósitos académicos.

PROFILE

Issues in Teachers' Professional Development

Vol. 16, No. 2, October 2014 ISSN 1657-0790 (printed) ISSN 2256-5760 (online)

doi: https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v16n2.40192

Hybrid Identity in Academic Writing: “Are There Two of Me?”

Identidad híbrida: “¿hay dos yo?”

Troy Crawford*

Martha Lengeling**

Irasema Mora Pablo***

Rocío Heredia Ocampo****

Universidad de Guanajuato, Guanajuato, Mexico

*crawford@ugto.mx

**lengeling@hotmail.com

***imora@ugto.mx

****rozetah@yahoo.com

This article was received on October 11, 2013, and accepted on January 24, 2014.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This paper explores the construction of identity in an academic learning environment in Central Mexico, and shows how identity may be linked to non-language factors such as emotions or family. These issues are associated with elements of hybrid identity. To analyze this we draw on language choice as a tool used for the construction of identity and for showcasing and defending identity through exploratory interviews with the bilingual students and teachers. The results draw our attention towards the role of non-linguistic variables and their relationship to emotional and contextual issues that influence how academic writing occurs within the school confines, where hybrid identities may be constructed for academic purposes.

Key words: Academic writing, attachment, detachment, hybrid, identity.

Este artículo explora la construcción de identidad en un medio de aprendizaje en el centro de México y muestra cómo la identidad puede estar relacionada con factores no lingüísticos, como las emociones o la familia. Estos factores están asociados con aspectos de identidad híbrida. Para analizar esto, nos basamos en la elección de lengua del usuario como una herramienta para la construcción de la identidad y para ilustrar y defender la identidad en entrevistas a fondo con alumnos y maestros bilingües. Los resultados atraen nuestra atención hacia el papel de variables no lingüísticas y su relación con factores emocionales y contextuales que influyen en la manera como ocurre la redacción en segunda lengua en la escuela, en donde las identidades híbridas pueden ser construidas para propósitos académicos.

Palabras clave: conectado, desconectado, escritura académica, híbrido, identidad.

Introduction

Identity in many aspects is shaped by language and conversely, language choices may relate to identity. Identity, in fact, like language, is both personal and social. Social identity denotes the various ways in which people understand themselves in relation to others, and includes the ways in which they view their past and future lived experiences, and how they may want to be viewed. The shaped self employs language as a tool for making its presence felt. Thus a person’s world-view is inextricably shaped by the language he or she decides to use (Miller, 1997; Olinger, 2011). The interaction of identity and language is a reality in a context such as the University of Guanajuato, where students are required to learn English in the university in order to obtain a degree. On the other hand, teachers are required to write in Spanish to maintain their employment. In other words, users are required to use a second language to fulfill social obligations.

The capacity of language as a symbol of individual identity cannot be overemphasized. This is possibly the most important feature in Mexican society, where English has a strong political feature powerfully shaped by the tense historical political relationship with the United States (Crawford, 2007, 2010). Early in life we individuals begin to use language to define our personalities in relation to each other, and later in life we continue to make use of language to define ourselves and the various roles we play in the community (Cheng, 2003; Waseem & Asadullah, 2013). Added to this in Mexico, both countries have a powerful on-going political/linguistic relationship (Condon, 1997). When people move into a context where the norms and practices are different from their own, it is to be expected that newcomers will learn the prevalent norms and values in order to achieve some degree of integration into the new language environment, and to enhance their ability to communicate and interact (Mills, 2002; Mok & Morris, 2010; Mokhtarnia, 2011). These adjustments may imply changes in self-perception as an author in an academic context.

Language Attitude and Identity

Haugen (1956) notes that language use is influenced by the attitudes and values of users and non-users (that is, those who refuse to use) of the language, both as an instrument of communication and as a symbol of group identity. Individual attitudes towards a language will impact, for example, on the value placed on the language, and invariably, on how much of it may be used by first language speakers or learnt by second language speakers. In other words, the status of the language in a particular society also influences the attitudes of speakers as well as non-speakers.

Wherever languages are in contact, one is likely to find certain prevalent attitudes of favor or disfavor towards the languages involved. These can have profound effects on the psychology of the individuals and their use of the languages.

In the final analysis these attitudes are directed at the people who use the languages and are therefore inter-group judgments and stereotypes (Haugen, 1956). When two languages come into contact, usually one language is dominant over the other (Spolsky, 1998). In the case of this study we have a situation where English is the dominant language because of institutional choice (Crawford, Mora Pablo, Goodwin, & Lengeling, 2013), but in practice “the language now belongs to those who use it . . . whether in its standard form or local forms” (Kachru & Smith 1985, p. 210). As we are viewing, for this study, the language as an object that belongs to the user, there is no theoretical framework that is directing or orienting the data. We are allowing the data to shape and mold the process in the form of discovery through blurred genres in the tradition of Geertz (Denzin & Lincoln, 2005). The reason for this is that bilingual writers are by definition placed into a category of being hybrid. Hybrids by definition are a complex group to understand. “In offensive parlance and in racist discourse, expressions in the meaning of the term ‘hybrid’ are used to often characterize persons of mixed racial or ethnic origin” (Wagner et al., 2010, p. 232). In TESOL (Teaching of English to Students of Other Languages) hybrid is frequently used in a reductionist manner to label non-native or bilingual writers as inferior in some sense (Holliday, 2005; Kubota, 2002). Research on psychological essentialism provides the following definition of how essence is thought about in everyday life and its painful connotations to people:

1. Essence is stable and inherent to its carrier and constitutes the carrier by causally determining its defining features. That is, it endows its carrier with permanent and unique attributes that are specific for all members of a category and constitute an inviolable identity (Kronberger & Wagner, 2007). It is transferred by descent, not by touch or other forms of proximity.

2. Essence is discrete. It is perceived as a yes-or-no affair; either an entity has it or not, there is no middle way. A living-kind exemplar cannot possess a certain quantity or degree of an essence. As a consequence, essences are mutually exclusive. An exemplar of a kind or category can only possess one specific essence.

3. Attributing an essence is coextensive with making a category a natural entity and naturalizes the defining features of the category’s exemplars. (Wagner et al., 2010, p. 234)

The same authors later make reference of the term essence and its relation in the following:

This definition brings us immediately to the case of hybrids. If the members of a kind or category are attributed an essence, then this attribution makes the exemplar inherently and unalterably different from the members of other kinds or categories and, because an essence resists blending and decomposition and cannot be divided or mixed with another essence without losing its function in defining a category, then any “essence mixture” cannot exert its “causal” powers in shaping the necessary and defining features of the mixed exemplars. Consequently, mixing the genes of two animal species or of two other essentialized categories creates a “non-entity” that is perceived as not belonging to any accepted category. Perceivers with an essentialist mindset will reject and also despise a “mixed exemplar.” (Wagner et al., 2010, p. 234)

As mentioned in the introduction, both students and teachers are dealing with the condition of being considered hybrid in the academic space. This circumstance of existing academically in a space that is socially constructed as hybrid brings consequences that are not necessarily dealt with directly in the course of academic work in the classroom, but are present in the social spaces where academics are performed. This situation also tends to determine to what degree a student or teacher may feel “attached” or “detached” to a given language. The act of

moving from family and other social networks to the larger societal matrix, studies of Strange Situation classifications in other cultures have sparked a lively debate on their universal versus culture-specific meaning. (Bretherton, 1992, p. 770)

The debate centers on how “attachment/detachment” is viewed in relation to our attitude towards knowledge and is reflected primarily in the relation between the writer and the reader (Mora Pablo, 2011; Vassileva, 2001). Our writing performance and debate occur in Central Mexico in a public university.

Method

We are interested in this research professionally in the sense that second language research is part of our practice in the world of academics. Another concern is the effectiveness of our program and the learning process of our students in the development of their academic writing in English during their BA studies. One question we ask ourselves continuously is if the training we give our students aids them along their journey to become part of an English academic writing community. In particular, we refer to the processes outside the realm of language, but directly involved in the transition of becoming a second language writer. Therefore, following a qualitative paradigm, we wanted to know how participants became second language writers. According to Maycut and Morehouse (1994), “qualitative research examines people’s words and actions in narrative, or descriptive ways closely representing the situation as experienced by the participants” (p. 2).

Participants

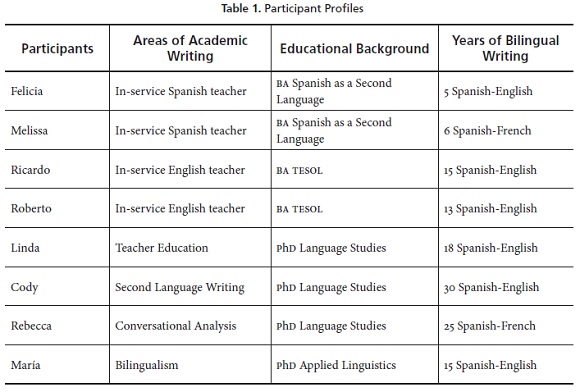

The eight participants in the study were selected purposefully in order to allow for representation of the different student types at the University of Guanajuato, specifically, within the two academic teacher training programs: a BA in TESOL and a BA in Spanish as a Second Language. The bilingual professors and students participated in the data gathering process as both researchers and participants. Nevertheless, there was a specific intent to select strong bilingual writers for the study because, in essence, they do not fit the classical model of identity and writer.

Technique: In-Depth Interviews—Multivocality

In-depth discussions with the participants was used. As Madriz (2000) points out, it brings into the research process a multivocality of participants’ perceptions and experiences. Through this method, personal emotions and opinions with regard to participants’ cultural backgrounds, educational backgrounds, attitudes toward other languages, and bilingualism are explored. The data collection consisted of individual recorded interviews following a semi-structured initial interview format taken from Ivanič (1998) that focused on the construction of authorial identity. Later, the follow-up interviews took on a more open and flexible pattern that emerged naturally. Interviews were chosen as a research tool because they can generate useful information about a lived experience and its meaning. Denzin and Lincoln (2005) refer to interviews as conversations and that an interview is “the art of asking questions and listening” (p. 643). However, interviews are influenced by the personal characteristics of the interviewer, including race, class, ethnicity and gender (Denzin & Lincoln, 2005). The objective of these interviews was to know more about their experiences in writing, not only in their native language, but also in other languages and to know if they perceived a preference for either one of the languages. The participants had the opportunity to select in which language they would like to be interviewed. Later, discussions with the co-researchers/respondents were carried out in-depth and added to the discussion. This discussion allowed us to interact directly with participants and provided opportunities for the clarification and extension of responses and follow-up discussion (Stewart & Shamsadani, 1990). This method is not new to either mainstream linguistics or feminist linguistics (Cameron, 1997).

Multiliteracies

The creation of a second language writing identity is a complex issue that involves decisions at many levels. These decisions affect the individual on both a personal level and on a collective level in the sense of what groups he/she identifies with and how he/she is accepted within circles (Busayo, 2010). In our context, our students are faced with a situation of being forced to acquire a second language writing identity in order to complete their undergraduate studies and the teachers are required to adopt a second identity to comply with academics inside the workplace. These requirements place them in a dual, forced multiliteracies situation. Matsuda, Canagarajah, Harklau, Hyland, & Warschauer (2003) mention the presence of multiliteracies in the following:

The term multiliteracies is becoming important in popular discourse in the context of post-modern cultural developments, the decentered workspace, and cyber-communication. The term refers to new ways of reading and writing that involve a mixture of modalities, symbol systems, and languages. A typical web page, for example, may involve still photographs, moving images (video clips), and audio recording in addition to written language. Apart from processing these different modalities of communication, “readers” will also have to interpret different sign-systems, such as icons and images, in addition to words. Furthermore, texts from languages as diverse as French and Arabic may be found in a site that is primarily in English. Different discourses could also be mixed—as legalese, medical terminology, and statistical descriptions, besides everyday conversational discourse. (p. 156)

Beside the assimilation of the literary complexities of the current globalized world, our students are also faced with the obligation to acquire a second “identity” as writers at a higher educational level. This necessity implies a complex set of emotions and situations which requires decisions that are interconnected beyond the defined boundaries of the university, where social definitions play a strong role in how identity is viewed. Table 1 provides a profile of the participants’ backgrounds for the study.

Discussion of Findings

There are two major themes which emerged from the data. One is an internal emotional battle within the writer. The other is a sense of loss in some cases and in others a sense of discovery in which the writers feel either “attached” or “detached” from a language.

The Authors’ Emotional Battles

As non-native writers, we must learn the hard way. Most of us feel that we are going to be judged stricter than native speakers. Rebecca explains that academic writing is something that you learn. Her own process led her to get more than acquainted with experts in the field of writing. Rebecca is aware that for her, the output of her writing must come with a pure French style. Having discussed this with her colleagues, we all have the perception of becoming “perfect” in what we write and how we do it. Most of us started our writing processes by reading and becoming familiar with the different writing conventions. Rebecca explains:

For example when I was writing my thesis, what I would do, and something my professor told me, in order to write academic articles and all that, you need to imitate someone. You need to get inspired by someone. So I chose the best in my flied and got inspired be her, I had to read many articles that she had written. So, in some way I was inspired by her style because in French you have to write, I believe, like the French. Organizing a serious and profound idea is not easy in any language. Much more in a language that at the end of the day is not yours.

Rebecca is conscious of who her audience is and writes in a totally different way compared to her own language (Spanish), and she is aware that even writing in her own language is difficult. Rebecca is Mexican and her postgraduate education has been acquired in France. Her own process is to know that it is through reading that one can become an expert at writing. Once again, as non-native writers, we feel that we have to write perfectly in order to fit in.

As already mentioned, non-native speakers-writers tend to first get acquainted by reading in order to start writing. We follow the experts and by doing so, we are somehow “copying” their style and trying to be part of a community that to start with is not ours due to the differences in the languages. The following student participant states:

I always try...to give more content...to give more content I don’t know...I don’t know if...I don’t know if by trying to explain my idea a little in the style of, I said it before about the Mexicans, right? Read and well I did not have a choice, you have to do the homework or you have to do the project, right? And that’s it. But the person who corrected me has helped. He said: Here, you don’t say it that way...the fact that I have studied Spanish here; speaking it every day has helped. (Melissa)

Or this other student participant comments:

And because I like to read a lot and I try to get you know different styles of writing from other people and I try different things so it’s always something new. (Roberto)

Perhaps we become better at doing something when we receive feedback. We can see from these three participants that asking somebody to read their work helped them to improve their writing. As non-native speakers we must feel comfortable with the “first audience” and, ideally, the first audience must be a native speaker since we think that this person knows more about what is trying to be learnt. We feel that this person is ready to give the appropriate feedback in order to help us grow as writers. This growth is often seen as learning how to manage a set of foreign conventions.

Writing may be seen as adhering to a set of writing conventions yet part of the writing process involves the person who is writing. When the person writing is taken into account in the forefront, then the building of a recognizable identity becomes important. Within the data we found the emerging theme of the writers’ emotions, whether they write in their native language or another language. One of the emotions found was a lack of security or an attempt to overcome the lack of security when writing. The following research participant explains how she feels:

I think I now feel more secure. For many years I didn’t feel I was secure enough to have that position of authority. But because I would start to write articles little by little and then became educated in the area of TESOL and then I had other opportunities to work, like editing. It was a very very long process and so sometimes I think people depend on a number of aspects. It may be easier for them to enter into that type of privileged writing or not and then sometimes people are more interested in teaching and so it may be a little bit more difficult. Myself, I think it was very difficult to enter into that privileged type of writing because you stumble, you fall, you skin your knees, you knock your head against the wall, you make a fool out of yourself and then little bit by little you figure out how to do it but how you do it is just you know understanding what you have to do, looking at lots of sources and almost bearing yourself, you know to this type of writing...to a group of people and you are always insecure at times as if they will accept you and if they understand what you wanted to get across. (Linda)

From the above excerpt we can see how the journey for this person to learn how to write has been long and at times filled with some setbacks. Perhaps this person felt vulnerable at the beginning but through experience she has become more confident as an academic writer. This person distances herself when explaining her setbacks and uses you as a way to include others in her setbacks and perhaps make a generalization.

The abovementioned excerpt was from a native English speaker and the following is from a non-native English speaker whose native language is Spanish. Both are academics and researchers. She writes academically more in her non-native language than in her native language. Interestingly she writes nostalgically about how she feels more comfortable with English instead of Spanish in the following quote:

And sadly I don’t write in Spanish that often anymore and most of what I write is in English—the academic part. I used to keep a diary, but now I don’t have the time to, and I realize that I am writing more in English than in Spanish. But I think it is just because here everything or most of the things I do are in English. (María)

Perhaps this teacher feels guilty that she is more at ease with English than her native language. Her use of a specific language for academic writing seems to be related to the fact that she has had many years of education in English and also the fact that she has to write in English for her career. Yet it is clearly expressed that something has been lost or maybe modified—from something pure to something hybrid. Another student comments on how he felt when he realized he had problems in Spanish, his native language. This realization seems in tune with what the above teacher commented on and represents their bilingual identities. The student mentions:

I remember when in the first semester taking a class in Spanish and that’s when I noticed that I couldn’t write in Spanish. For some reason there was like something in my brain that would lock or something when I wanted to put my thoughts into writing in Spanish...It was like, wow, wait a minute, how do I say this? How do I structure this in Spanish? I noticed I had quite a hard time doing that. Also one thing I knew that sentences can be longer, you can put a few comas there in Spanish. It’s not like in English. In English you go straight to the point and you have to say it in a structured matter. In Spanish you can beat around the bush...I can say that it is a little more eloquent. I find them complex and I don’t know to some extent they cause some kind of anxiety in me to just even thing about that. (Ricardo)

Both the teacher and student are bilingual people, yet English is more dominant in their academic writing. They seem to feel more at ease in English. Another student, whose native language is French, mentions how she would feel if she had to write in her native language should she decide to pursue a Master’s in France in the next excerpt:

And I asked myself if I could do it [a Master’s in France], if I could write in French after being in Mexico for so much time. I am afraid. I am afraid to return and to have to write academic essays in my own language. I think I am more at ease with Spanish right now. (Melissa)

Again we see how the second language (L2) has become more dominant for these people. This student realizes that she has adapted herself as a non-native speaker to be able to write in another language other than Spanish and she expresses how she feels about the possibility of writing in her native language: anxious. Again, this implies that the person may have lost something in the process of assimila-ting another language for the purpose of writing.

Another teacher/researcher uses the word rebel when describing himself. In the following data he seems to defy what the norm for academic writing is.

I guess I’m a person who is a rebel who goes against the structures and conventions as much as possible and I try to challenge and question anything that is connected to authority. I guess when I write I want to cause problems; that’s who I am. I want people to create a discussion. (Cody)

According to him, this disobedience is a way for him to question the authority of the norms of academic writing. This behavior could be part of his personality or even the result of a lack of confidence. At the same time it could also be just the act of academic writing which is “supposed” to create debate and discussion, but from the data so far it would seem that the controls of academic writing may be more about forcing conformity rather than generating diversity. Also, this situation might be an attempt to not lose fragments of identity, while transitioning to another language.

Another teacher explains how she approaches academic writing and her emotions in the following:

I am the type of person who when I have to write something, I need to be alone and I take my time. I feel anguish when I have to do things quickly and when I am working in a group I feel we have to be in agreement of certain things, but to write I have to be alone and focused. If not, I do not feel at ease. After my doctorate, I learned a lot, and you really get some confidence. But I am also very strict and at the same time I am timid to start a research project. I have never considered myself good at writing and I think that most people tend to have more of an ability of talk than to write. Yet, I am disciplined and I have had to do it. (Rebecca)

There are a number of emotions that this teacher expresses when she talks about how she has learned to write, the process of academic writing and the descriptions she uses. For her, writing is a solitary act that cannot be pressured. There is a sense of torment if she does not have the conditions she wants when writing. Studying a doctorate helped her in her process of becoming a more confident academic writer. Within this excerpt we also see her describe herself as disciplined, yet timid.

Regarding the opinions of students, the following student of the BA in Teaching Spanish as a Foreign Language program uses the words “freer” and “move around” to describe how she feels about academic writing in Spanish.

But in Spanish, because it is my mother language and I suppose I have ample knowledge of it, I feel I am freer to write. I can write an idea, move around the ideas, add more details and at the same time say something. (Felicia)

This student expresses how much more confident and independent she feels when writing in her own language. It should be mentioned that this student began her studies in our BA in TESOL program but changed to the BA in Teaching Spanish as a Foreign Language program because it was closer to what she wanted to do. Perhaps writing in her own language played a part in her decision-making towards writing and changing degree programs. This particular participant went on later to say in an informal conversation that English “is like putting on a straightjacket” and it (English) makes her lose her identity as a person when she is writing.

In this section we have seen how teachers and students have felt about learning to write academically in their own language or in another language. What is clear is that the process is complex and varies from one person to another and emotions seem to play a part in this complex process as well as identity shifting. The interesting point that the data seem to suggest is that issues concerning learning and language seem to be in the forefront of the decision-making process. The choice of language and its link to the person’s identity takes on an emotional role and the language shift or the decision to write in a second language appears to be based more on need than desire.

Identity Lost or Discovered: A Sense of Attachment and Detachment

For most participants, language choice is a symbol of identity and in that sense they seem to choose a language based on their writing abilities and their contexts. All participants are bilingual or multilingual and this characteristic helps them mediate identities and engage in a number of situations. This is where the sense of “commitment/detachment” becomes relevant to the data analysis because there were some participants who mentioned a very precise manner of attaching feelings and meanings to one language. The following excerpt mentions this aspect:

Participant: My first writing language would be English. (Ricardo)

Interviewer: OK, do you see the difference between the two YOUS in when you’re writing in those two languages?

Participant: Well, I would say in my English level—confident, ok, free flow, ok, in Spanish I see some anxiety my anxious self...nervousness, insecurity I would say in writing in Spanish (Ricardo)

This participant seems to have divided his repertoire based on how he feels when writing in one language or another. Since he has lived most of his life thus far in an English speaking country (15 years), he feels more confident with English. Even when he recognizes that Spanish is his first language, his own life experiences have shaped the way he perceives these languages. He continues explaining how he feels in Spanish:

In Spanish I take it a little bit slower. I would say, ok what am I writing about? Write about this ok, what first of all what’s the vocabulary I’m going to use. My vocabulary is not really developed in Spanish I can speak fluent Spanish but it’s not academic...I don’t have too much academic vocabulary I would say. (Ricardo)

He says his Spanish “is not academic” since he learned and used Spanish at home while he studied English formally at school. This seems to be the source of this distinction and in his current role as a BA student; he has made clear the uses and purposes of using English or Spanish.

Another participant, who is from France, shows an array of multiple languages: French as her first language, but also there is competence in Spanish, Italian, German, and English. She is currently studying for a BA in Spanish and has been exposed to the “Mexican way” of writing essays. She explains how she perceives this in the following extract:

Now I have two or three mistakes per essay but I have been told that my style is more European, at least French. But I have never tried to change it because I have never been asked to write as Mexicans do. Anyway, I don’t like the way Mexicans write because they write many things...and they have no structure, they don’t have a good structure. They say many ideas in different tenses, there is no clear order. Then, I try not to copy it; I try not to change my style because so far they haven’t said anything about this way of writing. (Melissa)

She evaluates the way she has improved her writing skills in Spanish; however, she admits that her style is “European”. She also points out that “the Mexican way of writing” is disorganized and does not follow a structure. She makes a comparison: “Spanish is more disorganized and French is more concise” (Melissa). Even when this participant might be influenced by other languages when writing in Spanish, she seems to reveal how she perceives French as “superior”.

Another student participant, whose first language (L1) is Spanish, makes a distinction between English and Spanish. She is studying for a BA in Spanish but has also studied English for a number of years:

Because, for example, in English, I guess, you have to write very concrete, the ideas like...period and then another idea. And in Spanish your ideas do not have to be concise, nor to the point, I feel that in Spanish we are given the opportunity to “echar rollo,” to “decorate” the text, to be more redundant. (Felicia)

This idea of being more redundant in Spanish has made a difference in the way she perceives one language. The manner with which she approaches a piece of writing in either language is connected to how she feels in one language or the other.

English is not my mother tongue. So, I think that it is easier for me in English, to be more precise. And if I wanted to decorate or follow and idea on and on, I wouldn’t know how if it is accepted in English or if what I want to say would be understood. But in Spanish, as it is my mother tongue, and I have more knowledge about it, I feel like...freer to write. I can write the idea, go on and on, “decorate it,” and at the same time say things. I feel freer in Spanish when I write. (Felicia)

The “freedom” this student participant refers to when writing in Spanish might be linked to the fact that she has been trained and encouraged to give more details in Spanish than in English. She makes reference to one particular moment in which she was taught that English “is more direct:”

I remember that when I was in an English class, the teacher gave us a piece of paper...An essay is done like this: First you have to write this, then here, the citation is like this . . . And in Spanish they didn’t give us like a written guide but it was mentioned. When you do an essay it is expected that you do this, that . . . But the only written example I saw was in my English class, that’s how they told me. (Felicia)

This observation seems to show that students are in a constant ambivalent relationship between what they want to do in writing and what the conventions in a language dictate. Even more, what they are taught in classes. Also, the manner in which a language is perceived places these participants in a continuum of stereotypes formed not only by what they have experienced but also by what they have been taught.

However, these feelings are not exclusively the students’. Teachers are also in an ambivalent position when referring to language choice. In order to choose a language, they face similar issues, but also the professional side has influenced the way they perceive the languages and their own identities when writing in one language or the other.

One researcher participant explains how she learned to write in her second language while working in an administrative position and how she thinks she is a different person when writing in her L2 (Spanish):

I think I probably learned how to write in the second language when I had to be in an administrative position and I had to look at other letters and realize “Ok this is how you do it here in Mexico” and I would try to more or less adapt that type of discourse to my discourse so I would say I am a different person when I am writing in Spanish. I have to adapt to a different type of language. It doesn’t bother me that it’s a different type. I just know that it can’t be the same in English. (Linda)

This change in identity when writing in her L2 seems to have no conflict with her identity in L1. On the contrary, she seems to have added another identity to her existing one. They are not against each other, but it seems that each one of them has a particular purpose and aim.

This is not always clear for all participants. Another researcher participant expresses confusion when defining his native language for writing:

I don’t know what my native language is for writing. In total I’ve written more in Spanish than in English, I can write faster and easier in Spanish than in English. When I write in Spanish I get less corrections and less observations than when I write in English but I’ve written more academic stuff in English than in Spanish so I really don’t know what’s my native language I just conform to what I have to do when I’m using one or the other. (Cody)

Moreover, the same participant seems to have created a link between the language and its purpose and sometimes it seems to be flowing between the personal and professional sides:

It depends on the topic, if it’s something I studied in Spanish I prefer Spanish and if it’s something I studied in English I prefer English if it’s a topic that’s core to my beliefs and the way I think I prefer Spanish if I’m talking about things that are outside of me I probably prefer English. (Cody)

Each language seems to have its purpose and it has been given meaning related to identity. This has encouraged the transformation and recreation of the individuals’ linguistic repertoire and they seem to be able, at this point in their lives, to attach meaning to the languages in a clearer manner.

The professional side has also affected language choice in some participants. In a context where their L1 (Spanish) is not frequently used, they have accommodated their linguistic repertoire to the circumstances. The following example from another researcher participant points out this accommodation:

I have to tell you that most of what I have written academically has been in French, of course. But recently, I have been doing things in Spanish and I’m learning (Rebecca).

Even when her L1 is Spanish, her academic life has taken her to write in her L2 (French). As she points out, lately, she has been writing in Spanish and it has been difficult to re-learn to write in her L1. This can be seen in the following extract from a different participant researcher:

And sadly I don’t write in Spanish that often anymore, and most of what I write is in English, the academic part. I realized that I was writing more in English than in Spanish. But I think is just because here everything...or most of the things I do, are in English. I write differently but the problem is that right now my dominant language in the environment and in what I do is English and that has influenced my Spanish writing. Maybe later is going to be back to Spanish but I find it easier to follow English conventions than Spanish ones, because, as I haven’t studied those like in a long time I don’t know now anymore...it is like confusion now in my mind. (María)

This may even take on the extreme position of almost apparent complete rejection of the writing process as Roberto, a student, states with almost hints of anger:

Well, if I think about it, what I write is at the end is pointless because all I got to do is turn in my work. I get a grade and then it goes in my files and that’s it so I’m a writer of papers that have no purpose other than getting a grade and then moving on but I don’t see the...I mean who cares what I think about a certain theory. Who cares, I mean I don’t see the point but anyway that’s what we are asked to do.

The detachment is such that it might seem to some that the language serves him little purpose. It is as if there were no real connection between him and the language in terms of academic writing. This internal process has an impact on the writer as a user of the language.

These participants once experienced the difficulties of learning a second language, but now that second language has become their dominant one. They have experienced a detachment of their own first language and are aware of it. Joining a new academic community has brought some changes in their language choice. They have appropriated a specific discourse as well as conventions and roles, but their identities remain a mixture of acceptance of and resistance to one language or the other according to their circumstances. What appears to give rise to the internal conflict in the writing process appears to be associated more with emotional or internal aspects of the individual rather than issues of knowledge about the conventions of writing.

Conclusion

The above data place the writers in an unusual situation. It is as if they were almost unsure at times of whom they are: “I don’t know what my native language is for writing” (Cody) and “it is like confusion now in my mind” (María), or maybe even complete rejection as it seems to be the possible conclusion. The elements that surround the construction of authorial identity on the surface are debated in terms of educational and professional choice by the individual as if they were exclusively a conscientious decision (Ivanič, 1998). Yet the data here are taking on a different direction that moves into a path of emotional turmoil, which in turn leads to a sense of attachment and detachment of the individuals, where internal elements are in a state of movement depending on what, where, and with whom they are writing. This does not suggest a disagreement with the cumulative work of researchers (e.g., Clark & Ivanič, 1997; Connor, 1996, 2002; Ivanič, 1998), but more of a door opening that shows that bilingual writers do not experience identity in exactly the same way as do monolingual authors. Moreover, the underlying difference is not about linguistics, rhetoric, or cultural patterns, but more of a personal issue of choice linked to professional or academic need. This need is often then transcended into a social space where issues of hybridity circulate as a peripheral form of classification of the writer, which in the future entangles the location of identity. This occurrence places the author in an unusual position where, on the one hand, there is a sense of being less because of hybridity and on the other a sense of conclusion depending on the degree of attachment or detachment to a given language.

This finding creates an internal conflict or clash. The participants are dealing with an internal struggle where two languages are at odds with each other. The clash seems to be a battle ground where “emotions” and “need” are placed in front of the user. Clearly, each user has made a choice as to which language she/he prefers to use. Nevertheless, as María said: “it is like confusion now in my mind,” and even though a choice has been made it does not mean that the other language has, in a complex manner, completely left the author’s identity.

The above implies that we need to focus our attention less on linguistic and rhetorical factors in writing as occurred in the past. Now, in this global world, we need to look closer at emotional issues and professional requirements that are in a constant state of change as we cross back and forth through the linguistic, emotional, educational, and professional boundaries of our societies.

References

Bretherton, I. (1992). The origins of attachment theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. Developmental Psychology, 28(5), 759-775.

Busayo, I. (2010). Identity and language choice: ‘We equals I’. Journal of Pragmatics, 42(11), 3047-3054.

Cameron, D. (1997). Performing gender identity: Young men’s talk and the construction of heterosexual masculinity. In S. Johnson & U. H. Meinhof (Eds.), Language and masculinity (pp. 47-64). Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Cheng, W. (2003). Intercultural conversation. Amsterdam, NL: Benjamins.

Clark, R., & Ivanič, R. (1997). The politics of writing. London, UK: Routledge.

Condon, J. C. (1997). Good neighbors: Communicating with the Mexicans (2nd ed.). Yarmouth, MA: Intercultural Press.

Connor, U. (1996). Contrastive rhetoric: Cross-cultural aspects of second language writing. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Connor, U. (2002). New directions in contrastive rhetoric. TESOL Quarterly, 36(4), 493-510.

Crawford, T. (2007). Some historical and academic considerations for the teaching of second language writing in English in Mexico. MEXTESOL Journal, 31(1), 75-90.

Crawford, T. (2010). ESL writing in the University of Guanajuato: The struggle to enter a discourse community. Guanajuato: University of Guanajuato.

Crawford, T., Mora Pablo, I., Goodwin, D., & Lengeling, M. (2013). From contrastive rhetoric towards perceptions of identity: Written academic English in Central Mexico. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 15(1), 9-24.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). (Eds.). The Sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed.). London, UK: Sage Publications.

Haugen, E. (1956). Bilingualism in the Americas: A bibliography and research guide. Alabama, US: University of Alabama Press.

Holliday, A. (2005). The struggle to teach English as an international language. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Ivanič, R. (1998). Writing and identity: The discoursal construction of identity in academic writing. Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins.

Kachru, B. B., & Smith, L. E. (1985). Editorial. World Englishes, 4(2), 209-212.

Kubota, R. (2002). The impact of globalization on language teaching in Japan. In Block, D. & Cameron, D. (Eds.) Globalization and language teaching (pp. 13-28). New York, NY: Routledge.

Madriz, E. (2000). Focus groups in feminist research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research, (pp. 835-858). London, UK: Sage Publications.

Matsuda, P., Canagarajah, S., Harklau, L., Hyland, K., & Warschauer, M. (2003). Changing currents in second language writing research: A colloquium. Journal of Second Language Writing, 12(2), 151-179.

Maycut, P., & Morehouse, R. (1994). Beginning qualitative research: A philosophical and practical guide. London, UK: Routledge.

Miller, J. (1997). Second language acquisition and social identity. Queensland Journal of Educational Research, 13(2). Retrieved from http://iier.org.au/qjer/qjer13/miller2.html

Mills, S. (2002). Rethinking politeness, impoliteness and gender identity. In J. Sunderland & L. Litoselliti, (Eds.), Gender identity and discourse analysis (pp. 69-90). Amsterdam, NL: Benjamins.

Mok, A., & Morris, M. (2010). An upside to bicultural identity conflict: Resisting groupthink in cultural ingroups. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(6), 1114-1117.

Mokhtarnia, S. (2011). Language education in Iran: A dialogue between cultures or a clash of identities. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 1998-2002.

Mora Pablo, I. (2011). The native speaker spin: The construction of the English teacher at a language department at a university in Central Mexico (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Canterbury Christ Church University, Canterbury.

Olinger, A. R. (2011) Constructing identities through “discourse”: Stance and interaction in collaborative college writing. Linguistics and Education, 22(3), 273-286.

Spolsky, B. (1998). Sociolinguistics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Stewart, D. W., & Shamsadani, P. N. (1990). Focus groups: Theory and practice. London, UK: Sage.

Vassileva, I. (2001). Commitment and detachment in English and Bulgarian academic writing. English for Specific Purposes, 20(1), 83-102.

Wagner, W., Kronberger, N., Nagata, M., Sen, R., Holtz, P., & Flores Palacios, F. (2010). Essentialist theory of ‘hybrids’: From animal kinds to ethnic categories and race. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 13(4), 232-246.

Waseem, F., & Asadullah, S. (2013). Linguistic domination and critical language awareness. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 70, 799-820.

About the Authors

Troy Crawford, (BA) Southern Oregon University, (MS) University of Guanajuato, (MA TESOL) University of London, (PhD) University of Kent, Canterbury. He has worked in ESL for 30 years at the University of Guanajuato and is a member of the Mexican National Research System focusing his research on identity in second language writing.

Martha Lengeling works at the University of Guanajuato and holds an MA TESOL (West Virginia University) and a PhD in Language Studies (University of Kent). She is the Editor of the MEXTESOL Journal and currently is a member of the Mexican National Research System. Her areas of research are teacher training and teacher identity formation.

Irasema Mora Pablo is a professor at the University of Guanajuato, Mexico. She holds a PhD in Applied Linguistics from the University of Kent, UK. She has conducted research in bilingualism, Latino studies, identity formation and native and non-native teachers and published chapters and articles in Mexico, the United States, and Colombia.

Rocío Heredia Ocampo, (BA) University of Guanajuato, (MA TESOL) University of Auckland, has worked in ESL for 18 years. She currently collaborates in the BA TESOL program and ESL program in the University of Guanajuato.

References

Bretherton, I. (1992). The origins of attachment theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. Developmental Psychology, 28(5), 759-775.

Busayo, I. (2010). Identity and language choice: ‘We equals I’. Journal of Pragmatics, 42(11), 3047-3054.

Cameron, D. (1997). Performing gender identity: Young men’s talk and the construction of heterosexual masculinity. In S. Johnson & U. H. Meinhof (Eds.), Language and masculinity (pp. 47-64). Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Cheng, W. (2003). Intercultural conversation. Amsterdam, NL: Benjamins.

Clark, R., & Ivanič, R. (1997). The politics of writing. London, UK: Routledge.

Condon, J. C. (1997). Good neighbors: Communicating with the Mexicans (2nd ed.). Yarmouth, MA: Intercultural Press.

Connor, U. (1996). Contrastive rhetoric: Cross-cultural aspects of second language writing. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Connor, U. (2002). New directions in contrastive rhetoric. TESOL Quarterly, 36(4), 493-510.

Crawford, T. (2007). Some historical and academic considerations for the teaching of second language writing in English in Mexico. MEXTESOL Journal, 31(1), 75-90.

Crawford, T. (2010). ESL writing in the University of Guanajuato: The struggle to enter a discourse community. Guanajuato: University of Guanajuato.

Crawford, T., Mora Pablo, I., Goodwin, D., & Lengeling, M. (2013). From contrastive rhetoric towards perceptions of identity: Written academic English in Central Mexico. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 15(1), 9-24.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). (Eds.). The Sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed.). London, UK: Sage Publications.

Haugen, E. (1956). Bilingualism in the Americas: A bibliography and research guide. Alabama, US: University of Alabama Press.

Holliday, A. (2005). The struggle to teach English as an international language. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Ivanič, R. (1998). Writing and identity: The discoursal construction of identity in academic writing. Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins.

Kachru, B. B., & Smith, L. E. (1985). Editorial. World Englishes, 4(2), 209-212.

Kubota, R. (2002). The impact of globalization on language teaching in Japan. In Block, D. & Cameron, D. (Eds.) Globalization and language teaching (pp. 13-28). New York, NY: Routledge.

Madriz, E. (2000). Focus groups in feminist research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research, (pp. 835-858). London, UK: Sage Publications.

Matsuda, P., Canagarajah, S., Harklau, L., Hyland, K., & Warschauer, M. (2003). Changing currents in second language writing research: A colloquium. Journal of Second Language Writing, 12(2), 151-179.

Maycut, P., & Morehouse, R. (1994). Beginning qualitative research: A philosophical and practical guide. London, UK: Routledge.

Miller, J. (1997). Second language acquisition and social identity. Queensland Journal of Educational Research, 13(2). Retrieved from http://iier.org.au/qjer/qjer13/miller2.html

Mills, S. (2002). Rethinking politeness, impoliteness and gender identity. In J. Sunderland & L. Litoselliti, (Eds.), Gender identity and discourse analysis (pp. 69-90). Amsterdam, NL: Benjamins.

Mok, A., & Morris, M. (2010). An upside to bicultural identity conflict: Resisting groupthink in cultural ingroups. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(6), 1114-1117.

Mokhtarnia, S. (2011). Language education in Iran: A dialogue between cultures or a clash of identities. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 1998-2002.

Mora Pablo, I. (2011). The native speaker spin: The construction of the English teacher at a language department at a university in Central Mexico (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Canterbury Christ Church University, Canterbury.

Olinger, A. R. (2011) Constructing identities through “discourse”: Stance and interaction in collaborative college writing. Linguistics and Education, 22(3), 273-286.

Spolsky, B. (1998). Sociolinguistics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Stewart, D. W., & Shamsadani, P. N. (1990). Focus groups: Theory and practice. London, UK: Sage.

Vassileva, I. (2001). Commitment and detachment in English and Bulgarian academic writing. English for Specific Purposes, 20(1), 83-102.

Wagner, W., Kronberger, N., Nagata, M., Sen, R., Holtz, P., & Flores Palacios, F. (2010). Essentialist theory of ‘hybrids’: From animal kinds to ethnic categories and race. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 13(4), 232-246.

Waseem, F., & Asadullah, S. (2013). Linguistic domination and critical language awareness. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 70, 799-820.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

License

Copyright (c) 2014 Troy Crawford, Martha Lengeling, Irasema Mora Pablo, Rocío Heredia Ocampo

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.