Published

The Impact of Authentic Materials and Tasks on Students’ Communicative Competence at a Colombian Language School

El impacto de materiales y tareas auténticas en el desarrollo de la competencia comunicativa de estudiantes en un instituto colombiano de idiomas

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n1.56763Keywords:

Authenticity, authentic materials, authentic tasks, communicative competence, pedagogical project (en)autenticidad, competencia comunicativa, materiales auténticos, proyecto pedagógico, tareas auténticas (es)

This article reports on a study carried out in a foreign language school at a Colombian public university. Its main purpose was to analyze the extent to which the use of authentic materials and tasks contributes to the enhancement of the communicative competence on an A2 level English course. A mixed study composed of a quasi-experimental and a descriptive-qualitative research design was implemented by means of a pre-test, a post-test, observations, semi-structured interviews, surveys, and diaries. The findings showed that the use of authentic materials and tasks, within the framework of a pedagogical project, had an impact on students’ communicative competence progress and on the teaching practices of the experimental group teacher.

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n1.56763

The Impact of Authentic Materials and Tasks on Students’ Communicative Competence at a Colombian Language School

El impacto de materiales y tareas auténticas en el desarrollo de la competencia comunicativa de estudiantes en un instituto colombiano de idiomas

César Augusto Castillo Losada*

Edgar Alirio Insuasty

María Fernanda Jaime Osorio

Universidad Surcolombiana, Neiva, Colombia

*cesar.castillo@usco.edu.co

**edalin@usco.edu.co

***mariafernanda.jaime@usco.edu.co

This article was received on April 1, 2016, and accepted on October 23, 2016.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Castillo Losada, C. A., Insuasty, E. A., & Jaime Osorio, M. F. (2017). The impact of authentic materials and tasks on students’ communicative competence at a Colombian language school. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 19(1), 89-104. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n1.56763.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This article reports on a study carried out in a foreign language school at a Colombian public university. Its main purpose was to analyze the extent to which the use of authentic materials and tasks contributes to the enhancement of the communicative competence on an A2 level English course. A mixed study composed of a quasi-experimental and a descriptive-qualitative research design was implemented by means of a pre-test, a post-test, observations, semi-structured interviews, surveys, and diaries. The findings showed that the use of authentic materials and tasks, within the framework of a pedagogical project, had an impact on students’ communicative competence progress and on the teaching practices of the experimental group teacher.

Key words: Authenticity, authentic materials, authentic tasks, communicative competence, pedagogical project.

Este artículo da cuenta de un estudio llevado a cabo en un instituto de lengua extranjera de una universidad pública en Colombia. Su propósito principal fue analizar el impacto del uso de materiales y tareas auténticas en el desarrollo de la competencia comunicativa de los estudiantes de un curso de inglés con nivel A2. Se implementó un estudio mixto compuesto de un diseño investigativo cuasi-experimental y descriptivo-cualitativo mediante pre y pos test, observaciones, entrevistas semiestructuradas, encuestas y diarios. Se encontró que la implementación de materiales auténticos y tareas auténticas, en el contexto de un proyecto pedagógico, incidió en el mejoramiento de la competencia comunicativa de los estudiantes y de la práctica pedagógica del docente encargado del grupo experimental.

Palabras clave: autenticidad, competencia comunicativa, materiales auténticos, proyecto pedagógico, tareas auténticas.

Introduction

Materials play a fundamental role in the language classroom since they are the means used by the teacher to facilitate learning that occurs both inside and outside the classroom. Authentic materials, that is, materials which have not been designed for teaching purposes, are potential learning tools due to the authenticity of the language and their intimate relation with the communicative language teaching approach (Hall, 1995; Tomlinson, 1998).

Despite the existence of opposing perspectives among scholars with regard to the potential usefulness of authentic materials in the language classroom, what proved to be more appropriate for our research team was to explore this issue so as to assure the use of communicative English lessons at a Colombian foreign language school. Therefore, this article is the account of a small-scale research carried out in response to the prevalence of pre-communicative teaching practices in the same educational context (Jaime Osorio & Insuasty, 2015) and the lack of classroom-based strategies which could address this problem in Colombia. Thus, this study sought to assess the effectiveness of using authentic materials and tasks to enhance students’ development of the communicative competence and to provide the English language teaching (ELT) community with further insights into communicative English language learning experiences in foreign contexts.

This report starts by presenting a review of the literature so as to highlight key tenets such as communicative competence, authenticity, and authentic materials and tasks in the English language teaching and learning process. In a subsequent section, the methodology, the research methods, and the step-by-step process implemented are also presented. Then, a quantitative presentation and qualitative description of the results are made in order to proceed to the discussion and conclusion section. Finally, some final remarks are provided to encourage further studies that can lead to the improvement of the teaching quality in the ELT field in general.

Theoretical Framework

In this section, general concepts about communicative competence will be first introduced. Next, constructs surrounding the terms authenticity, authentic materials, and authentic tasks are examined in order to depict the role of authentic materials in the language classroom.

Communicative Competence

In this study, Bachman’s (1990) definition of communicative competence is adopted. It is described as the knowledge of language components and as the acquisition or performance of two types of abilities, that is, organizational competence and pragmatic competence. The organizational competence is concerned with the ability to control the structure of language (grammatical competence) along with the knowledge of the conventions for joining utterances to form a text, according to rules of cohesion and rhetorical organization (textual competence).

Pragmatic competence refers to the ability to control the functional features of language (illocutionary competence) and the sensitivity to the conventions of language use in context (sociolinguistic competence).

Figure 1 illustrates the components of the organizational and pragmatic competence as proposed by Bachman (1990). Bachman’s model does not only include the different components posited by Canale and Swain (1980), but also expands his framework of communicative language ability to include the strategic competence. The strategic competence refers to the ability to compensate in performance for incomplete linguistic resources in a second language.

From the perspective of classroom communicative competence, we agree with Johnson’s (1995) view which advocates that students should be provided with ample opportunities to use the language for both meaning and form focused instruction. Also, students should have opportunities for language use in formal and informal conversations within a context that is meaningful and realistic whilst both linguistic (phonology, grammar, vocabulary, and discourse) and pragmatic (functions, variations, interactional skills, and cultural framework) aspects are focused.

We agree that the above competencies should be developed in the classroom in an integrated way. If a teacher decides to have students just practice, for instance, the structural or the lexical systems of the target language regardless of the other components of classroom communicative competence, the learners will seriously be limited in their interactional possibilities to understand and use the target language in a purposeful way.

Authenticity and Authentic Materials

According to Morrow (1977), it has been difficult for scholars to agree on a definition of the terms authenticity, authentic materials, and authentic language use in language teaching terms. The complexity of this inconsistency lies in the multiple areas in which the term authenticity falls, and the participants involved. According to Mishan (2005), the concept of authenticity in language learning throughout history has fallen into three different groups: communicative approaches, materials focused approaches, and humanistic approaches.

The communicative approach has highlighted authenticity as the need to communicate, which presupposes an emphasis on meaning rather than on form. Contrary to this, the materials focused approach allowed the implementation of other approaches such as the scholastic approach, which consisted in breaking down words into their constituent parts, and the inductive approach, whereby readers infer grammar rules out of authentic texts. Finally, the humanistic approach sees the learner as a whole where all the sensory repertoire of the brain is required (Mishan, 2005). It is therefore evident how the term authenticity has been understood and applied in the search of achieving that ultimate goal which is communication.

As to the role of authentic materials in the language classroom, both Nunan (1988) and Hedge (2000) agree that they are not produced for language teaching purposes and do not have “contrived or simplified language.” Thus, newspapers, magazines, videos, or maps are clear examples of authentic materials. Nonetheless, Morrow (1977) goes further and claims that “an authentic text is a stretch of real language, produced by a real speaker or writer for a real audience and designed to convey a real message of some sort” (p. 13). This latter definition certainly complements the concept that language authenticity and authentic materials should be understood within the foreign/second language learning context as any kind of spoken or written act which does not contain any traces or signs of language teaching intervention, and emerges from the producer’s own first language, culture, and needs for communication.

Given the understanding and characteristics of authentic materials, different scholars have valued and criticized their use in the foreign/second language classroom. On the one hand, Hedge (2000) claims that authentic materials are appropriate means for students to cope with the authentic language of the real world. Also, Peacock (1997) remarks that authentic materials “may increase learners’ levels of on-task behavior, concentration, and involvement in the target activity more than artificial materials” (p. 152). Moreover, Harmer (1994) claims that learners can greatly benefit from authentic materials as these types of input help students improve their language production, acquire the language in an easier manner, and increase their confidence when using the language in real life situations.

On the other hand, Shoomossi and Ketabi (2007) argue that “non-authentic materials are as valuable as authentic materials. Indeed, there are some situations in which authentic materials are useless—especially when the learners’ receptive proficiency is low” (p. 152). This view is shared by Kienbaum et al. (as cited in Al Azri & Al-Rashdi, 2014) since they assert that there are no significant differences in learners’ performance e.g., between learners using authentic materials and others who use traditional materials. Also, Kilickaya (as cited in Al Azri & Al-Rashdi, 2014) believes that using authentic materials with weak learners frustrate and demotivate them because they lack the required skills and vocabulary to deal successfully with the presented text.

In order to overcome these difficulties, Hwang (2005) suggests that when learners are challenged by the complexity of some authentic language features, it is necessary to provide pedagogical support by calling students’ attention to equivalent expressions that are different in syntax or wording/phrasing in the languages that are learned. Hence, since authenticity does not necessarily mean “good,” just as contrivance does not mean “bad” (Clarke, 1989; Cook, 2003; Widdowson, 1979, 2003), this study placed the use of authentic materials as a strategy to complement the use of non-authentic materials, and with the goal of fulfilling the learners’ communicative needs.

Authentic Tasks

Scholars such as Brown and Menasche (as cited in Shoomossi & Ketabi, 2007, p. 152) provide a rather controversial view by noting that “there is probably no such thing as ‘real task authenticity’ since classrooms are, by nature, artificial.” However, Widdowson (as cited in Mishan, 2005, p. 70) claims that “it is the relationship between the learner and the input text, and the learner’s response to it, that should be characterised as authentic, rather than the input text itself.” Thus, in foreign language learning contexts where exposure to the language being learned is scarce, there is an imperative need to implement materials and design tasks which will enable learners to meaningfully and purposefully use the language.

According to Nunan (2001), “a communicative task [is] a piece of classroom work which involves learners in comprehending, manipulating, producing, and interacting in the target language while their attention is principally focused on meaning rather than form” (p. 10). This definition is then refined by Bygate, Skehan, and Swain (as cited in Mishan, 2005, p. 68) as they argue that a task is “an activity in which: meaning is primary; there is some sort of relationship to the real-world; task completion has some priority; and the assessment of task performance is in terms of task outcome.” As both definitions refer to in-class work with the added values of interaction and real-life simulation, it is then worth looking at the distinction made by Nunan (2001) between what he terms “real-world” tasks and the more traditional “pedagogic tasks.” Nunan (2001) states that “real-world tasks require learners to approximate, in class, the sorts of behavior required of them in the world beyond the classroom . . . pedagogic tasks, engage learners in tasks they are unlikely to perform outside the classroom” (p. 40). Furthermore, McGrath (2002) highlights the use of authentic tasks in the classroom as they help learners replicate or rehearse the communicative behaviors which will be required of them in the real world.

Hence, in order to design authentic tasks which involve learners in situations that emulate natural authentic language use, it is vital to consider the six guidelines proposed by Mishan (2005) with regard to task authenticity:

- Reflect the original communicative purpose of the text on which they are based.

- Be appropriate to the text on which they are based.

- Elicit response to/engagement with the text on which they are based.

- Approximate real-life tasks.

- Activate learners’ existing knowledge of the target language and culture.

- Involve purposeful communication between learners.

Research Design

The research methodology was developed from a mixed study perspective that integrated a quasi-experimental and a descriptive-qualitative research design. According to Hernández Sampieri, Fernández-Collado, and Baptista Lucio (2006), the quasi-experimental research design deliberately manipulates, at least, one independent variable in order to observe its effect and relationship with one or two dependent variables. In this particular design, subjects are not assigned to the groups randomly because those groups are already formed before the treatment. This research study intended to analyze the extent to which the implementation of authentic materials and tasks contribute to the enhancement of the communicative competence in an A2 level English course in a school of foreign languages at a Colombian university.

Accordingly, two A2 level English courses (Henceforth: Course A and Course B) were chosen. Course A was considered as the control group whereas Course B was treated as the experimental group. Different teachers oriented these courses, and due to the nature of this quasi-experimental research project, the treatment was only applied to Course B. A pre-test and a post-test were administered to both the control and the experimental groups so as to compare the degree of effectiveness of the treatment. This quasi-experimental research project was conducted by following four stages.

In the first stage, the research group started with the selection of groups and the pre-test implementation. Course A was composed of nine students from 18 to 45 years of age whereas Course B had fourteen students whose ages varied from 16 to 40. Students from both groups came from different socioeconomic backgrounds. After the selection of the groups, a pre-test was conducted in both courses.

The second stage of the project began with a diagnosis which consisted of an analysis of the pre-test results to establish the strengths and the weaknesses of students’ communicative competence, plus an analysis of the syllabus which was the departure point for designing the pedagogical intervention in Course B. As it was vital to apply a treatment that was congruent with both the research and course aims, the pedagogical intervention was devised following a methodological framework which highlighted the systematic use and implementation of authentic materials and tasks.

Upon completion of the treatment and imple-mentation of the research methods, the research team, professors (three full-time and one part-time) at Universidad Surcolombiana proceeded to conduct the post-test on both groups so as to measure the impact of the treatment applied. This process was called stage three. The analysis of the gathered data was performed in stage 4 after obtaining the results of the post-test implementation to course A and B. All data collected from the pre-test and the research methods in stages 1 and 2 respectively were also considered in the analysis in order to come up with the final conclusions.

Pedagogical Intervention

This particular framework was made of two complementary parts: The first one was shaped by a series of enabling pedagogical tasks dealing with issues such as advertisements, video viewing of city tours in Melbourne (Australia), map reading activities, readings about Cristiano Ronaldo and Roger Federer and one about a city tour in Neiva (without audio, just subtitles). The second part was concerned with the development of two pedagogical projects (Tourism in Neiva and Pen-pals) which entailed actions in which learners actively participated in the creation of contents and interacted with their peers, visitors and native English speakers. Authentic materials were chosen from different cultural products from several English speaking countries, and in accordance with the contents and topics established in the course syllabus.

Table 1 shows the implementation process, which consisted of the design of two authentic projects (Tourism in Neiva and pen-pals). Then, a series of authentic tasks was outlined in order to fulfill the objectives of the project.

Data Collection Instruments

Lesson observation: Five classes were tape-recorded for further study. Similarly, participation in the English club was taped in order to analyze the students’ motivation and the authentic materials impact on the development of the students’ communicative competence. A group of three observers—all of them professors who participated as researchers—used skills checklists and rubrics so as to organize the information. The taped-recorded lessons were distributed evenly among the observers for analysis, followed by a group session to exchange viewpoints and draw conclusions from the data collected with this instrument.

Survey: Two surveys were administered to Course B. Survey A, which was conducted after each implementation in class, collected information about aspects related to the authentic materials impact on students’ overall communicative performance. Survey B, which was conducted at the end of the term, aimed to collect information about the authentic project, the conversation club, and the overall impact of authentic materials.

Teacher’s diary: The Course B teacher was asked to reflect and write about certain aspects related to authentic materials use and the students’ attitudes towards authentic materials (e.g., newspaper and magazine articles, videos), authentic tasks (e.g., brochure design), and the pedagogical projects (e.g., tourism in Neiva), and their communicative competence progress.

Interview: Three interviews were carried out. Both teachers were asked about their teaching practices in Courses A and B. Similarly, the native speaker in charge of the conversation club was interviewed in order to obtain information on his appraisal of students’ progress with regard to their speaking performance.

Results

In this section, the results of the different data gathering instruments are shown in the following order: pre-test and post-test administered to students of both the experimental and control groups, lesson observations, the ongoing assessment, the surveys administered to the experimental group students, the experimental group teacher’s diary, and the interviews of the teachers.

Pre-test and Post-test

Participants in the study took a Key English Test (KET) at the beginning and at the end of the course. The KET commercial sample assesses language performance through three papers: reading and writing (R&W), which weighs 50 points; listening (LIST), which carries 25 points; and speaking (SPEAK), which carries 25 points. The test is designed to last two hours approximately and during its implementation, candidates are expected to understand simple written information, produce simple written texts, and understand announcements and other spoken material when people speak reasonably slowly.

Results of the pre-test can be observed in Table 2. By observing the average total scores it can be concluded that both the experimental and the control groups started with a similar skill level. Although their marks were expected to be higher due to the complexity of the test and the assessment scale, there was a visibly low performance in their listening and speaking skills.

On the other hand, Table 3 shows the post-test results. Although students in both groups show progress in their communicative competence, Course B evidences a slightly higher level of progress in their overall performance. According to the test results, the abilities which improved the most were reading and writing, which rose five points.

Lesson Observations

Five lessons were tape-recorded to analyze the students’ motivation, authentic materials, tasks, and project’s impact on the development of the students’ communicative competence. The lesson observation form consisted of three columns that permitted a better organization of the data by grouping categories (authentic materials, authentic tasks, communicative competence, and teaching practices) that brought together the viewpoints of the three observers.

Among the results found, materials were perceived as appropriate and useful in all the classes by students and observers. They also provided students with opportunities to use their speaking skills, helped students use the target language in a communicative manner, and provided the teacher with the opportunity to develop communicative activities.

Another important finding from the observation process regarding the students’ communicative competence was that in four out of five interventions the authentic tasks and authentic materials contributed positively to the development of the grammatical, textual, and illocutionary competences, evident in their written products and their oral speech (see Ongoing Assessment section). There was also evidence of a contribution to the development of the sociolinguistic competence since in three of the five interventions students were prompted to use their listening skills to understand and become more sensitive to dialects, register, nature, cultural references, and figures of speech.

Ongoing Assessment

The four interventions in the conversation club with a native speaker and the project’s product were also tape-recorded in order to assess the students’ communicative competence progress by means of the Assessing Speaking Performance: Level A2 (Examiners and speaking assessment in the Cambridge English: Key exam) rubric.

Results from the observation in the conversation club showed that students seemed to understand the native speaker but could not maintain a simple, basic conversation. The native English speaker did most of the talking as students’ answers were limited. The students’ main problems were related to pronunciation and a low range of vocabulary which were represented in the continuous asking for clarifications to understand utterances in their conversations with the native speaker.

The project’s product took the form of oral presentations in a display session open to the academic community members at the end of the course. Several students and proficient English-language speakers were invited to the display session. During the students’ presentation, oral interactions with the attendees to the event were tape-recorded. As in the conversation club, the Assessing Speaking Performance: Level A2 rubric was used to assess the students’ speaking performance. Results of the observation showed that students were able to exchange information and react appropriately to questions, but sometimes needed some prompts or support to do so. They misunderstood some questions, especially due to unfamiliar pronunciation or intonation patterns.

Moreover, students showed a high degree of simple grammatical forms that were easy to understand. Although most of the time they used appropriate vocabulary and intonation when answering questions, they sometimes tended to pronounce some words incorrectly.

Finally, the pen-pals project was aimed at measuring the students’ written competence progress with the exchange of at least three letters per participant. A total of forty-two letters were expected; however, only thirteen were submitted by seven participants. Despite the low number of letters collected, the following features were identified based on a rubric which assessed the grammatical, sociolinguistic, and textual competences.

The students used basic grammar structures (simple present, past, future) and vocabulary (adjectives) to build phrases and sentences with connectors like and, but, and because. Most of them communicated their messages and provided information to their pen-pal properly, and only one of the students showed problems in introducing and developing ideas. In terms of text organization, the texts were outlined easily by the reader. They all began with a greeting and tried to answer the questions posed by their pen-pals; they also attempted an appropriate introduction and ending and there was evidence of logical sequencing. There were some non-impeding errors in spelling and grammar.

Surveys

Survey A

After each implementation, Survey A collected information about aspects related to the authentic materials impact on students’ overall communicative performance.

In general, students had a positive perception of the authentic materials used in class. In terms of interest, understanding, usefulness, and motivation, most students found that the authentic materials were interesting (71%) and useful (70%). In a slightly lower proportion, but not less important, students believe that authentic materials are motivating, although 34% (about 5/14) of the students found them difficult to understand (see Figure 2).

Survey B

Survey B was conducted at the end of the term. It collected information about the pedagogical project, the conversation club, and the overall impact of authentic materials.

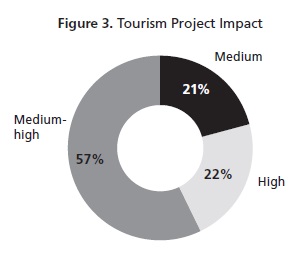

Figure 3 describes the percentages and scales with which students located the impact of the Tourism in Neiva project during the course. When being asked about the impact that the tourism project had in their English language learning process, 79% of the students stated that the project had a high and medium high impact. Among the reasons to justify their answer was the finding that all students admitted that their participation in the different tasks and the use of the materials provided to achieve the tasks objectives facilitated learning English as a foreign language. For instance, students who actively engaged in the conversation club (43%) thought that this task gave them more opportunities to practice the language for real purposes outside the classroom. Despite this high percentage, 21% of the students placed the impact on a medium scale.

In relation to the English conversation club experience, 86% of the students described the experience to be compelling, interesting, enriching, and appealing. Whilst 7% of them found the vocabulary acquisition as relevant when attending the conversation club, another 7% found the native speaker difficult to understand. Results can be observed in Figure 4.

The survey also gathered information on the students’ perception of their communicative competence enhancement as a result of their participation in the project and task. The skills they recognized to have had more improvement were reading, listening, and grammar and vocabulary, as can be assessed in Table 4.

Teacher’s Diary

The Course B teacher wrote on a teacher’s diary form about certain aspects related to authentic materials use, students’ attitudes towards authentic materials, authentic tasks and the authentic project, and students’ communicative competence progress.

According to the teacher the authentic materials used were entertaining and interesting, appropriate for the development of the class and helped the students use the target language in a communicative way. Moreover, the teacher thinks the materials were in accordance with the students’ target language level of competence and helped them to use their productive skills with different language purposes such as giving explanations, persuading, asking questions, negotiating factual and cultural meanings of words, phrases, sentences, and messages in the target languages.

All the materials were appropriate for the development of the class. They were carefully chosen and analyzed before presenting them to the students. The materials were part of an organized plan to teach them not only new vocabulary or grammar patterns, but to recognize strategies used by the authors and to critically respond to those intentions. [Students] also created contents based on the materials used.

Moreover, when analyzing the impact of tasks and authentic materials in the language skills, the teacher believes that students were given more chances to read and speak in the foreign language because most of the authentic materials were printed papers or videos. The tasks that made part of the intervention plan gave students opportunities to communicate in an oral way and to develop different micro-skills for speaking, reading, and listening, for instance, asking and answering questions, skimming and scanning, or listening for details. The teacher believes that even though writing was the less used ability, students did have the chance to create short texts according to the conventions given by the expected level (A2 from the Common European Framework).

Students were asked to communicate orally in order to check their understanding of the authentic materials content. They were asked to describe, analyze, summarize, and criticize not only the information received but the author’s intentions when creating the material. They were also able to create contents (questions for an interview, information about touristic places in Neiva, summaries of songs, etc.). By working in groups they collaborated to create those contents negotiating a final product in an oral way.

A final reflection made by the teacher regarding the students’ communicative competence was that there was a need to analyze students’ productive skills so as to obtain an overall view of students’ performance, as well as pupils’ further exposure to authentic materials to promote the enhancement of their competences.

I think they were exposed to different dialects and registers, but I am not sure if they can recognize cultural references or figures of speech by listening to different audios with no image provided. I think that they recognize basic differences among dialects and registers but they need more exposure and awareness to be able to identify them in different settings and communicate with other people accordingly.

Interviews

Three interviews were carried out. Both Course A’s and B’s teachers were interviewed about the teaching practices employed in their respective courses. Similarly, the native speaker in charge of the conversation club was interviewed in order to obtain information on his appraisal of the students’ progress regarding their speaking performance.

Control Group Teacher

Course A teacher mentioned that he implemented different strategies, activities, and authentic materials such as debates, videos, or games with the control group. Some of these activities took place in the classroom and others were developed by students in a virtual learning environment that was used as a repository of materials (authentic and non-authentic).

Also, the teacher believes it is quite difficult to take in extra activities due to the brief class time/period provided by the institution. According to the teacher,

If you want to do any extra activity aside from what you have planned based on the course book, it becomes really difficult. You’d better do nothing, otherwise you can’t catch up, or you may need not to cover every unit page.

Thus, despite the control group teacher’s having used strategies, activities, and authentic materials which complemented the course program established by the institution, he did not use the authentic materials within the development of authentic tasks that promoted a meaningful and purposeful use of the language in the real world. The authentic input was then limited to the implementation of isolated activities.

Experimental Group Teacher

Course B teacher was asked about the advantages and disadvantages of using authentic materials in the institution courses. Among other strategies, she mentioned that students can have first-hand contact with the foreign language, learn a wide range of vocabulary, and get cultural awareness. Also, she believes that by watching authentic videos, reading authentic written materials, or listening to a native speaker from an English speaking country, not only students but teachers also can benefit. She mentioned having learnt new vocabulary and expressions while selecting the materials and preparing her classes.

On the other hand, the teacher mentioned that it is fairly difficult to identify disadvantages when using authentic materials, and added that:

When working with authentic materials, what is required by any teacher is a high sense of commitment with what you are doing, and a carefully planned set of actions. You also need to be alert to any changes because they need to be done on time. This may require more preparation time from the teacher, but I am sure that any teacher who loves his/her job purpose will do it without too many regrets.

According to the teacher, authentic materials (such as comics, videos, and articles) are beneficial for students. Nevertheless, they will not generate any major changes in the teaching practices or students’ communicative competence by themselves. It is in a planned articulation of materials and tasks within a project framework where authentic materials will make a difference. In other words, in her perception, it is tasks (what students do with the materials) and not the authentic materials per se that provokes learning.

Conversation Club Teacher

The native speaker in charge of the conversation club perceived that the planned activities (e.g., games, contests) allowed students to slightly develop their oral ability as he thinks that “with intermediate level students, progress is always gradual and much slower than that of beginners or elementary level students.” Nonetheless, when asked about the students’ speaking performance in the conversation club and on the day of the display session, the teacher commented: “I noted that students were speaking with much more confidence the day of the fair. Most of them interacted and communicated their ideas about tourism with ease. In class, I did much of the talking.” Hence, since the activities planned and implemented by the teacher in charge of the conversation club were not designed in alignment with the objectives of the pedagogical project, this perception confirms the experimental group teacher’s assertion that authentic input itself is not sufficient, and highlights the need to integrate the use of those authentic materials and tasks within a broader pedagogical action.

Discussion

Based on the aims stated in this study and the data gathered using varied research methods, this final section is structured in three broad categories, explained next.

The Role of Authentic Materials and Tasks in the A2 English Course

To start with, all the materials selected to complement the course syllabus, that is, magazines, videos, advertisements, newspapers, city maps, brochures, postcards, and entry tickets, were culturally and linguistically rich. The classroom observations and the insights from the experimental group teacher confirmed that the cultural content inherent in the materials impacted positively on the students’ motivation, curiosity, and attention as there was a constant natural desire of enquiry from students to their teacher and peers with regard to the characters, places, and activities described in all materials. This reflects Tomlinson’s (1998) view of authentic materials as tools to expose and help students to acquire authentic language use by providing learners with opportunities to use the language while the learners’ curiosity and attention is maintained.

Furthermore, this improved classroom environment motivated the teacher not to focus solely on the due completion of the school curriculum, but to enrich their teaching practices with communicative activities. There was evidence that the materials implemented in class helped students use the target language in a communicative manner because they read and exchanged real life information. Both the materials and proposed activities encouraged students to find information about their own culture and use the target language to answer questions and talk about foreign and national places, customs, and traditions. However, a few of the students seemed to be confused and overwhelmed about the input they received and the tasks they were asked to complete. This last fact seems to suggest that the linguistic richness of authentic materials resulted in higher degrees of language complexity for learners, which is one of the controversial issues brought up by the supporters and critics of the role of authentic materials in language learning.

Based on experiences throughout the course, the experimental group teacher recognized that authentic materials played an important role in the enrichment of the students’ vocabulary range, and in increasing their cultural awareness and level of attention. However, the teacher also highlighted the need for teachers in general to develop expertise in the implementation of authentic materials as there are possible “drawbacks” such as inefficient time management, overlapping of learning objectives, and wrong selection of materials whilst using them in class. In order to facilitate this process, it is suggested one follow a very well-structured plan or framework which prevents teachers from using authentic materials in an isolated way or just as “fillers.” Within this framework, each lesson is to be planned in a detailed way by taking into account the selection of materials and the transitions between the pre-activity, the actual activity, and the post-activity. In general terms, a high sense of commitment from the teacher as well as an in-service training or follow-up plan are strongly required if beneficial effects are to be sought in an English course based on the use of authentic materials and tasks.

Impact of Using Authentic Materials and Tasks

In general terms, two types of impact from using authentic materials and tasks were evidenced in this research. The first one is concerned with the headway students made in the development of their communicative competence in the target language. The second one deals with the enhancement of the teaching practices of the experimental group teacher.

Learners’ Communicative Competence

On a scale from 0.0 to 5.0, the pre-test results were somewhat similar in the experimental group (average score: 3.5) and the control group (average score: 3.4). The post-test results show that both groups made progress in terms of their proficiency enrichment. Whereas the experimental group achieved an average score of 3.9, the control group’s final average score was 3.7. As can be seen, the progress of the experimental group can be rated at 0.4 and the control group at 0.3. The low number of interventions in the experimental group and the fact that the control group’s teacher also implemented some authentic materials can be argued as a possible explanation for the minimal difference between the two groups. Another possible reason for this situation can be found in Kienbaum et al. (as cited in Al Azri & Al-Rashdi, 2014, p. 252) who stated “that there are no significant differences in learners’ performance: between learners using authentic materials and others who use traditional materials.”

However, it is worth assessing the effects of the authentic materials with other lenses. The experimental group instructor contends that

Materials on their own can help students develop their listening and reading skills. Nonetheless, it is the merge of the materials with a set of authentic tasks what leads to a successful development of the four language skills and the targeted competences for this chosen level.

It could be argued then that the complexity of the language learning process goes beyond the use of a single method or variable, and requires teachers to carefully design lessons which highlight and integrate the learner’s context, needs, and learning objectives.

Teaching Practices

In addition to their impact on the development of the students’ communicative competence, authentic materials are also believed to enhance the teacher’s professional performance. Contrary to Miller’s (2005) position that authentic materials are “too difficult and time consuming to select, edit, and prepare” (p. 5), in the teacher’s diary, the experimental group teacher admitted the positive impact these types of materials had on her teaching practices. She stated that authentic materials enabled her to enrich her teaching practices as the wide variety of authentic input allowed her to plan authentic tasks and activities that promoted the use of the language for communicative purposes. What is more, the experimental group teacher also claimed that these materials foster less controlled interaction between students as they can participate in functional activities such as oral reports, oral presentations, information exchange, mingling activities, and social activities such as projects, creative writing, group discussions, interviews, and debates (Jaime Osorio & Insuasty, 2015). This clearly confirms Peacock’s (1997) suggestion that “teachers should try authentic materials in their classrooms, as they may increase their learners’ levels of on-task behavior, concentration, and involvement in the target activity more than artificial materials” (p. 9).

On the other hand, despite the control group teacher having pointed out in the interview that it is difficult to do any extra activity in class due to the brief class time provided; the experimental group teacher denied this to a great extent. She supported the feasibility of using authentic materials and encouraged their use as an alternative to the prevailing pre-communicative activities which have been used by most of the institution’s faculty.

Building a Methodological Framework to Explore Authentic Materials and Tasks in the English Language Classroom

Planning to use authentic materials in an A2 level English classroom in a foreign language learning context proved to be a well-thought-out task. As suggested above, authentic materials need to be explored within a thorough methodological framework. This activity will enable learners to acquire both receptive and productive skills, and will provide them the opportunity to put into practice what they learn whilst developing pedagogical communicative projects. A good example of a methodological framework is the above mentioned pedagogical intervention that was designed and executed in Course B.

Within this methodological framework, both tasks and all the language skills were integrated as a way to develop the learners’ communicative competence which, according to Lomas, Osoro, and Tusón (1993), is concerned with “the acquisition of skills to understand and produce not only grammatical, but also appropriate statements.”

It was also confirmed that the use of varied types of authentic materials, within a systematic pedagogical and methodological framework, enabled the teacher to create more opportunities for communicative practice based on the students’ interests and needs. In this sense, it is also worth mentioning that the implementation of authentic materials in an isolated manner may fall short in the exploitation of the linguistic and cultural richness of the input, and in the development of the students’ communicative competence, because it could be seen merely as a temporary solution to the delivery of pre-communicative teaching practices.

Finally, despite the need for a well-defined plan, it is important to note that this plan should not be rigid and that it can be modified or adjusted according to the teacher’s perception and learners’ response. This flexibility of the methodological framework provides teachers with a tool to demystify the belief that authentic materials can only be used with learners whose language level competence is high enough to cope with the language complexity of the materials.

Conclusions

Given the linguistic and cultural nature of the authentic input and the learners’ level of competence, it can be concluded that an appropriate and effective implementation of authentic materials in foreign language learning contexts greatly depends not only on the relationship between the materials and the school’s educational context but also on the teacher’s experience dealing with this type of materials and the pedagogical support offered to learners when using them. Similarly, authentic materials lead the teacher to a continuous reflection process in which he/she is free to intervene in his/her own teaching practice. Therefore, the use of authentic materials in the language classroom must be strongly encouraged as they have a positive impact on the students’ linguistic and affective domains. Nonetheless, it is still required that further studies are conducted so as to shed more light on the best uses of authentic materials in language learning and the cultural issues encountered whilst implementing them.

References

Al Azri, R. H., & Al-Rashdi, M. H. (2014). The effect of using authentic materials in teaching. International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research, 3(10), 249-254.

Bachman, L. F. (1990). Fundamental considerations in language testing. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, 1(1), 1-47.

Clarke, D. F. (1989). Communicative theory and its influence on materials production. Language teaching, 22(2), 73-86. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444800014592.

Cook, G. (2003). Applied linguistics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Hall, D. (1995). Materials production: Theory and practice. In A. C. Hidalgo, D. Hall, & G. M. Jacobs (Eds.), Getting started: Materials writers on materials writing (pp. 8-14). Singapore, SG: SEAMO Regional Language Centre.

Harmer, J. (1994). The practice of English language teaching. London, UK: Longman.

Hedge, T. (2000). Teaching and learning in the language classroom. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Hernández Sampieri, R., Fernández-Collado, C., & Baptista Lucio, P. (2006). Metodología de la investigación [Research methodology]. Mexico City, MX: McGraw-Hill.

Hwang, C. C. (2005). Effective EFL education through popular authentic materials. Asian EFL Journal, 7(1), 1-12.

Jaime Osorio, M. F., & Insuasty, E. A. (2015). Analysis of the teaching practices at a Colombian foreign language institute and their effects on students’ communicative competence. HOW, 22(1), 45-64. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.22.1.133.

Johnson, K. E. (1995). Understanding communication in second language classrooms. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lomas, C., Osoro, A., & Tusón, A. (1993). Ciencias del lenguaje, competencia comunicativa y enseñanza de la lengua [Language sciences, communicative competence, and language teaching]. Barcelona, ES: Paidós Ibérica.

McGrath, I. (2002). Materials evaluation and design for language teaching. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press.

Miller, M. (2005). Improving aural comprehension skills in EFL, using authentic materials: An experiment with university students in Nigata, Japan (Unpublished master’s thesis). University of Surrey, Australia.

Mishan, F. (2005). Designing authenticity into language learning materials. Bristol, UK: Intellect.

Morrow, K. (1977). Authentic texts in ESP. In S. Holden (Ed.), English for specific purposes (pp. 13-15). London, UK: Modern English Publications.

Nunan, D. (1988). The learner-centred curriculum. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139524506.

Nunan, D. (2001). Designing tasks for the communicative classroom. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Peacock, M. (1997). The effect of authentic material on the motivation of EFL learners. ELT Journal, 51(2), 144-156. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/51.2.144.

Shoomossi, N., & Ketabi, S. (2007). A critical look at the concept of authenticity. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 4(1), 149-155.

Tomlinson, B. (1998). Materials development in language teaching. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Widdowson, H. G. (1979). Explorations in applied linguistics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Widdowson, H. G. (2003). Defining issues in English language teaching. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

About the Authors

César Augusto Castillo Losada worked until 2016 as an assistante profesor in the English Language Teaching Program at Universidad Surcolombiana. He holds an MA in Translation Studies from the University of Newcastle (UK), and a BA in English Language Teaching from Universidad Surcolombiana.

Edgar Alirio Insuasty holds a PhD in Education from Universidad Interamericana de Educación a Distancia (Panamá). He is currently working as an associate professor for the EFL Teacher Education Program at Universidad Surcolombiana. He is co-author of several books and articles in the EFL professional field.

María Fernanda Jaime Osorio is a full-time professor in the EFL Teacher Education Program at Universidad Surcolombiana. She holds an MA in Teaching English as a Foreign Language from Universidad Internacional Iberoamericana. She is the director of the Research Group ilesearch.

References

Al Azri, R. H., & Al-Rashdi, M. H. (2014). The effect of using authentic materials in teaching. International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research, 3(10), 249-254.

Bachman, L. F. (1990). Fundamental considerations in language testing. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, 1(1), 1-47.

Clarke, D. F. (1989). Communicative theory and its influence on materials production. Language teaching, 22(2), 73-86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0261444800014592.

Cook, G. (2003). Applied linguistics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Hall, D. (1995). Materials production: Theory and practice. In A. C. Hidalgo, D. Hall, & G. M. Jacobs (Eds.), Getting started: Materials writers on materials writing (pp. 8-14). Singapore, SG: SEAMO Regional Language Centre.

Harmer, J. (1994). The practice of English language teaching. London, UK: Longman.

Hedge, T. (2000). Teaching and learning in the language classroom. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Hernández Sampieri, R., Fernández-Collado, C., & Baptista Lucio, P. (2006). Metodología de la investigación [Research methodology]. Mexico City, MX: McGraw-Hill.

Hwang, C. C. (2005). Effective EFL education through popular authentic materials. Asian EFL Journal, 7(1), 1-12.

Jaime Osorio, M. F., & Insuasty, E. A. (2015). Analysis of the teaching practices at a Colombian foreign language institute and their effects on students’ communicative competence. HOW, 22(1), 45-64. http://dx.doi.org/10.19183/how.22.1.133.

Johnson, K. E. (1995). Understanding communication in second language classrooms. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lomas, C., Osoro, A., & Tusón, A. (1993). Ciencias del lenguaje, competencia comunicativa y enseñanza de la lengua [Language sciences, communicative competence, and language teaching]. Barcelona, ES: Paidós Ibérica.

McGrath, I. (2002). Materials evaluation and design for language teaching. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press.

Miller, M. (2005). Improving aural comprehension skills in EFL, using authentic materials: An experiment with university students in Nigata, Japan (Unpublished master’s thesis). University of Surrey, Australia.

Mishan, F. (2005). Designing authenticity into language learning materials. Bristol, UK: Intellect.

Morrow, K. (1977). Authentic texts in ESP. In S. Holden (Ed.), English for specific purposes (pp. 13-15). London, UK: Modern English Publications.

Nunan, D. (1988). The learner-centred curriculum. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139524506.

Nunan, D. (2001). Designing tasks for the communicative classroom. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Peacock, M. (1997). The effect of authentic material on the motivation of EFL learners. ELT Journal, 51(2), 144-156. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/elt/51.2.144.

Shoomossi, N., & Ketabi, S. (2007). A critical look at the concept of authenticity. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 4(1), 149-155.

Tomlinson, B. (1998). Materials development in language teaching. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Widdowson, H. G. (1979). Explorations in applied linguistics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Widdowson, H. G. (2003). Defining issues in English language teaching. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Ene Alas, Aleksandra Ljalikova, Merle Jung. (2023). CLIL teacher beliefs as they emerge working in tandem. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education, 11(2), p.229. https://doi.org/10.1075/jicb.22001.ala.

2. MARÍA FERNANDA JAIME OSORIO, CLAUDIA CAMILA CORONADO RODRÍGUEZ. (2018). Impacto de los materiales del programa de inglés en una universidad pública de Colombia. Cuadernos de Lingüística Hispánica, (32), p.175. https://doi.org/10.19053/0121053X.n32.2018.8127.

3. Jennifer Schneider. (2024). Digital Literacy at the Intersection of Equity, Inclusion, and Technology. Advances in Educational Technologies and Instructional Design. , p.325. https://doi.org/10.4018/979-8-3693-2591-9.ch014.

4. Mahmoud Abdi Tabari, Jingyuan Zhuang, Mahsa Farahanynia. (2025). Task repetition and L2 written performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Second Language Writing, 70, p.101255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2025.101255.

5. Endzhe Latypova. (2020). FOREIGN LANGUAGE COMPETENCE DEVELOPMENT USING CLIL AMONG STUDENTS IN RUSSIAN UNIVERSITIES. Humanities & Social Sciences Reviews, 8(4), p.755. https://doi.org/10.18510/hssr.2020.8475.

6. Kevin Papin. (2022). L’impact de tâches communicatives de réalité virtuelle sur la volonté de communiquer à l’extérieur de la classe : perceptions d’apprenants de FLS à Montréal. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 78(1), p.52. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr-2020-0117.

7. Faridah Fauziyah, Sri Sumarni. (2025). Utilizing Authentic Materials to Improve Listening and Speaking Skills: A Narrative Inquiry. Indonesian Journal of Foreign Language Studies, 2(1), p.37. https://doi.org/10.65576/indofes.v2i1.14.

8. Chinaza Solomon Ironsi. (2023). Improving Communicative Competence Levels of Pre-Service Teachers Through Spoken-Based Reflection Instruction. Journal of Education, 203(3), p.678. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220574211044543.

9. Aleyda Jasmin Alfonso Vargas, Paola Ximena Romero Molina. (2023). Authentic Materials And Task Design: A Teaching Amalgam. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 25(1), p.118. https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.18581.

10. Luis Carlos Martínez Méndez, Sally Alexandra Pedraza González. (2023). Cultural awareness through task-based learning using authentic materials. Paradigmas Socio-Humanísticos, 5(1), p.29. https://doi.org/10.26752/revistaparadigmassh.v5i1.674.

11. Faridah Fauziyah, Sri Sumarni. (2024). Utilizing Authentic Materials to Improve Listening and Speaking Skills: A Narrative Inquiry. Indonesian Journal of Foreign Language Studies, 1(1), p.27. https://doi.org/10.65576/indofes.v1i1.5.

12. Addisu B. Shago, Elias W. Bushisso, Taye G. M. Olamo. (2024). Beliefs of EFL University Instructors about Teaching Listening in Integration with Speaking, Ethiopia. Sage Open, 14(4) https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440241296581.

13. Mark R. Emerick. (2019). Explicit teaching and authenticity in L2 listening instruction: University language teachers' beliefs. System, 80, p.107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.11.004.

14. Mia Kreca, Constanza Mabel Carreño Ríos, Paz Alezandra Ríos Moscoso, Catalina Constanza Badilla Murilla. (2026). Exploring how authentic materials help contextualize teaching practices in the EFL classroom. Ducere: Revista de Investigación Educativa, 4(2), p.e202513. https://doi.org/10.61303/2735668X.v4i2.92.

15. Paola Julie Aguilar-Cruz. (2018). Herramienta multimodal basada en tareas para el aprendizaje del inglés en el grado sexto en Florencia, Caquetá (Colombia). Ciencias Sociales y Educación, 7(14), p.63. https://doi.org/10.22395/csye.v7n14a4.

16. Marina V. Terskikh, Olga A. Zaytseva. (2023). Didactic potential of authentic advertising texts in Russian as a foreign language classes. Neophilology, (4), p.767. https://doi.org/10.20310/2587-6953-2023-9-4-767-778.

17. Jennifer Schneider. (2021). Enhancing Higher Education Accessibility Through Open Education and Prior Learning. Advances in Higher Education and Professional Development. , p.210. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-7571-0.ch011.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

Copyright (c) 2017 PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.