High School EFL Teachers’ Identity and Their Emotions Towards Language Requirements

La identidad de profesores de secundaria de inglés como lengua extranjera y sus emociones acerca de los requisitos de lengua

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n2.60220Keywords:

English as a foreign language, language policy, language requirements, teacher identity, teacher emotions (en)identidad del profesor de inglés, inglés como lengua extranjera, política de lengua, requisitos de lengua, sentimientos de los profesores (es)

This is a study on high school English as a foreign language Colombian teacher identity. Using an interpretive research approach, I explored the influence of the National Bilingual Programme on the reconstruction of teacher identity. This study focuses on how teachers feel about language requirements associated with a language policy. Three instruments were used to collect the data for this research: a survey to find out teachers’ familiarity with the policy and explore their views on the language policy and language requirements and other aspects of their identity; autobiographical accounts to establish teachers’ trajectories as language learners and as professional English teachers; and semi-structured interviews to delve into their feelings and views on their language policy and requirements for English teachers.

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n2.60220

High School EFL Teachers’ Identity and Their Emotions Towards Language Requirements

La identidad de profesores de secundaria de inglés como lengua extranjera y sus emociones acerca de los requisitos de lengua

Julio César Torres-Rocha*

Universidad Libre, Bogotá, Colombia

*julioc.torresr@uniulibrebog.edu.co

This article was received on September 20, 2016, and accepted on March 9, 2017.

How to cite this article (APA, 6th ed.):

Torres-Rocha, J. C. (2017). High school EFL teachers’ identity and their emotions towards language requirements. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 19(2), 41-55. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n2.60220.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This is a study on high school English as a foreign language Colombian teacher identity. Using an interpretive research approach, I explored the influence of the National Bilingual Programme on the reconstruction of teacher identity. This study focuses on how teachers feel about language requirements associated with a language policy. Three instruments were used to collect the data for this research: a survey to find out teachers’ familiarity with the policy and explore their views on the language policy and language requirements and other aspects of their identity; autobiographical accounts to establish teachers’ trajectories as language learners and as professional English teachers; and semi-structured interviews to delve into their feelings and views on their language policy and requirements for English teachers.

Key words: English as a foreign language, language policy, language requirements, teacher identity, teacher emotions.

Este es un estudio sobre la identidad de profesores de inglés de secundaria en Colombia. Se exploró la influencia del Programa Nacional de Bilingüismo en la construcción de la identidad profesional de los profesores de inglés usando un enfoque investigativo interpretativo. Este estudio se centra en cómo se sienten ellos con respecto a los requisitos de lengua asociados con la política de lengua. Se utilizaron tres instrumentos para recolectar información: una encuesta para averiguar la familiaridad de los profesores con las políticas y explorar otros aspectos de su identidad; narrativas autobiográficas para establecer las trayectorias de los docentes como aprendices y profesores de lengua; y entrevistas semi-estructuradas a los participantes seleccionados aleatoriamente para profundizar en sus sentimientos y perspectivas sobre la política de lengua y sus requisitos para profesores.

Palabras clave: identidad del profesor de inglés, inglés como lengua extranjera, política de lengua, requisitos de lengua, sentimientos de los profesores.

Introduction

The present study deals with how language requirements associated with language policies affect English as a foreign language (EFL) teachers’ professional identity since teachers, as agents of both the formation of social learning and of professional identities (Wenger, 2000), are essential for the design and implementation of any educational policy. The reason for this interest has to do with the implementation of foreign language policies in Colombia with a rather unsuccessful outcome in the last decade. However, the real impact of language policies on teacher identity is yet to be established. With this purpose, it is important to recognise the different aspects that have been found to be part of professional language teachers’ identities. For instance, teachers’ intercultural competence (Duff & Uchida, 1997), their language learning experiences, their beliefs or conceptions and practices (Borg, 2006), and their trajectories or imagined futures represent essential parts of language teacher identities. Also, their status as non-native English speaker teachers (NNEST), who “can be good role models for English language learners but that they might lack knowledge about the target language and cultural norms” (Menard-Warwick, 2008, p. 617), is part of their identities. All these issues have been taken into consideration in previous studies, but little research has been conducted on how language requirements associated with a language policy can impact identities as far as emotions, perceptions, and trajectories.

According to Day (2004), in teacher education, one important goal is to prepare teachers who are informed and flexible to manage the imposed changes in the curriculum and education policies while trying to understand issues such as teachers’ sense of educational aim, practices, teacher identity, and agency. Interestingly, as Beijaard (1995) asserts, high school (HS) teachers’ identity is essentially linked to their subject area, which is the case of the present study of HS EFL teachers who face imposed changes, requirements, and policies in Colombia. In my view, the top-down strategy implemented by the National Ministry of Education (MEN in Spanish) up to now has affected teachers’ professional identity in different ways, but in what positive or negative ways? I consider it necessary to evaluate the impact on teachers’ identity of the previous National Bilingual Programme (NBP) before embarking upon a new programme called “Colombia Very Well”, intended for the 2015-2025 period. Therefore, I would like to explore the following questions and achieve the objectives proposed in this study.

Questions

In what way do HS EFL teachers feel that the language requirements associated with the national bilingual policy affect their identity as language learners and as professional language teachers?

What other aspects do EFL teachers feel have influenced the development of their identities?

Objectives

To explore HS EFL teachers’ perception of language requirements associated with the NBP.

To determine participants’ trajectories as language learners and teachers.

To find out the positive or negative effects that the language requirements cause in teacher identity as language learners and professional language teachers.

To identify other aspects teachers perceive influence their identity besides language proficiency.

Colombian EFL Context

The Colombian school system is divided into two types of schools: private schools and state schools. The first group is self-funded and represents 10% of the schools in the country. The second sector is the official school group where most of the Colombian children study; it represents 90% of the schools and is funded by the state, specifically the MEN. Schools are structured into common levels of study for basic education. Basic primary education, year levels 1 to 5 and basic secondary education, year levels 6 to 9. Years 10 and 11 of secondary education are supposed to be for humanities, sciences, and technical-vocational secondary education. This study concentrates on secondary education teachers who belong to the public sector of education and teach 11- to 16-year-old children from grades 6 to 11.

Problematic Situation

Policies usually take into consideration teachers’ competences or more specifically subject knowledge but not their experience and their knowledge of the sociocultural or socio-political context; at least this is the case of the NBP in Colombia. In 2006, the MEN decreed that English in schools had to be strengthened and they created a “Bilingual Bogotá” programme, and afterwards, a “Bilingual Colombia” programme. Both programmes targeted the whole private- and state-school sectors, aiming at fostering the development of proficiency in “standard” varieties of English (American and/or British) in primary and secondary education.

However, these programmes were not welcome or fully supported by scholars in Colombia (González, 2007; de Mejía, 2006). They state that the lack of attention to the linguistic complexity of the country and the limited notion of bilingualism (Spanish-English) perpetuate inequalities in terms of linguistic prestige and do not permit the construction of a more tolerant Colombian society. They also mention the inadequacy of professional development models established by NBP, the need to deconstruct the English language teaching’s (ELT) prevailing neo-colonial discourses, the construction of a local discourse of ELT, and the creation of mechanisms of dialogue between policy makers, and teacher educators and researchers.

A foreign language policy was established in Colombia in 2006 through a national bilingual programme (Spanish-English). This language policy has not been as successful as the authorities expected due to different factors. To me, they are: first, a top-down approach of language policy without taking into account teachers’ viewpoint; second, the implications of a national policy in terms of the scope of the NBP, and a lack of English teachers’ professional development; third, the inattention to indigenous languages in the Colombian territories, presuming the nation is a monolingual and mono-cultural society and therefore denying the multicultural and multilingual nature of the nation-state (de Mejía, 2006). According to Blackledge (2002), many times, “democratic, multilingual societies that apparently tolerate or promote heterogeneity, in fact undervalue or appear to ignore the linguistic diversity of their population” (p. 69). For this scholar, “a liberal orientation to equal opportunity for all masks an ideological drive toward homogeneity, a drive that potentially marginalizes or excludes those who either refuse or are unwilling to conform” (p. 69).

English language requirements for students and teachers have been a conflicting issue in the ELT field in Colombia due to various reasons. One reason is the neoliberal policies of recent governments; another is the promotion of only one language (English) for the purpose of globalisation and internationalisation which underlie the objectives of linguistic imperialism and native speakerism, and thirdly, the imposition of a standardised language competence for not only HS students and teachers but also university students and professors. In sum, English requirements might generate opportunities, development, and internationalisation, but they can also bring about marginalisation, lack of access, and confusion for language students and teachers in the Colombian context as well.

In this paper, I have presented first a short introduction of the rationale and the EFL Colombian context of study. In the next sections, three important constructs for the study will be introduced: community of practice, identity, and language policy. After this, the methodology, techniques used, and the participants are presented. Finally, data analysis is explained and the findings of a three-stage case study are presented using a sequential order in order to lead the reader to a final section on discussions, conclusion, and implications for further research.

Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

Community of Practice (CoP)

Learning, understood as social participation, implies not only involvement in the activities of the communities of practice one belongs to but also the construction of subjectivities and identities in relation to those communities. These identities are constructed based on shared meanings. Wenger (1998) understands the learning communities as a net of interconnected dimensions (meaning, practice, community, and identity) that define each other and characterise the learning-development relationship. In Wenger’ s conception, community is understood as a social configuration in which what one does is defined as something worth doing and one’s participation is important. In this way, one’s identity is constructed and communicated in various discourse forms, reflecting how learning changes who we are and how we become members of a determined community by creating personal histories. This process shows modes of belonging or identification: engaging, imagining, and aligning with the practices of a community (Wenger, 2000).

According to Wenger (2010), identities are formed within a CoP, which can be regarded as a social learning system. In this sense, the Colombian ELT is a CoP which has emergent structures, complex relationships, dynamic boundaries, on-going negotiation of identity, and cultural meaning. It is also a simple social unit where learning defines who we are. Therefore, both the concepts of identity as well as of CoP are essential parts of Wenger’s theory because they are interdependent. Besides, “identity reflects a complex relationship between the social and the personal where Learning is social becoming” (Wenger, 2010, p. 183).

In the CoP, competences and experiences lead to peripheral learning and partial participation, and the tension between them results in knowledge transformations in order to prevent stagnation and uncritical reproduction from happening. It is here where the sense of identity is constructed in the present; it also includes the past and the future in the trajectory toward the goal. However boundaries, understood by Wenger (2000) as fluid and tacit limits that define the CoP, can have positive and negative effects on the members of the community. In the ELT community in Colombia, shared practice, by its very nature, creates identity boundaries; however, imposed language policy requirements might create limitations or lack of access. The latter type of boundaries are artefacts representing language exams or requirements, which instead of bridging over boundaries in a community, can create marginalisation because they might be misinterpreted or interpreted blindly and therefore might affect learners’ and teachers’ identity.

To sum up, “If knowing is an act of belonging, then our identities are a key structuring element of how we know” (Wenger, 2000, p. 238). In the same way, knowing, learning, and sharing knowledge are parts of belonging or identifying. Also, identity is crucial to social learning systems for three reasons according to Wenger (2000):

First, our identities combine competence and experience into a way of knowing. Second, our ability to deal productively with boundaries depends on our ability to engage and suspend our identities. Third, our identities are the dynamic constructs in which communities and boundaries become realised as an experience of the world. (p. 239)

Boundaries are the product of sharing learning but they might be used to exclude or marginalise others when imposed from an external authority rather than constructed in a CoP. This might be the case of the language requirements established by the MEN.

Identity as Language Learner and as Professional Language Teacher

Researchers have recognised the need to study learners’ identity in the last two decades i.e. the interrelationship between identity and L2 learning (Block, 2006; Day, 2004; Norton, 2000; Pavlenko & Blackledge, 2004) and teachers’ identity issues and their impact on teaching. According to Varghese, Morgan, Johnston, and Johnson (2005), it is necessary to distinguish between research on teachers’ professional identity in general and language teacher identity. In the latter, sociocultural, sociolinguistic, and ethnic considerations take centre stage. Varghese et al. summarised the most important issues in identity research as the following: First, “identity is multiple, shifting, and in conflict; second, identity is crucially related to social, cultural, and political context; and third, identity is being constructed, maintained, and negotiated primarily through discourse” (p. 35). A perspective of identity from a social psychology posture is adopted and it is articulated in the present study with the theory of CoP mentioned above. In the same way, the trajectories of HS EFL teachers as learners and as language professionals are explored.

In social psychology, identity entails having a personal and a social identity (Liebkind, 2010). Social identity is based on an individual’s membership in social groups. Therefore, language teachers’ personal identity is based on their personal biography, interests, likes/dislikes, and knowledge—including beliefs, personal theories, and personal practical knowledge—whereas their social identity is defined through multiple memberships: a member of a collectivity of teachers; the membership of a certain social class with certain restricted access to power, a certain income group, and educational level; and their membership in a cultural or national entity (Norton, 1997). For example, “a teacher might identify strongly with a disadvantaged school community, or a teacher might include him or herself in the collectivity of all English teachers of a nation as opposed to policy makers or students in general” (Glass, 2012, p. 138). He/she might feel like a non-native speaker of English as opposed to a native speaker, he/she might or might not feel proficient in English, and he/she might be encouraged or threatened by educational policies vis-a-vis advancing professionally.

Interest in teacher identity in the ELT field is fairly recent (Liu & Xu, 2011; Norton & Early, 2011; Tsui, 2007). A review of the literature shows that three main themes have been widely discussed. The first is “the relationship between teachers’ linguistic positions and professional identity” (Liu & Xu, 2011, p. 590). These studies explore how the dichotomy of native-speakers (NS) / non-native-speakers (NNS) has troubled NNS teachers, making them feel inferior and incompetent as legitimate language education professionals (Jenkins, 2005; Park, 2012; Pavlenko, 2003). The second theme explores conflicts between social and professional identities (Varghese et al., 2005) and suggests that there is an undeniable relation between teachers’ professional identities and their socially constructed identities (e.g., gender, race, and ethnicity). These previously mentioned studies defend a holistic, dynamic view of understanding how the negotiations between teachers and the wider socio-cultural contexts have shaped their professional identity. The third theme explores how teacher identity is mediated in educational reforms (Liu & Xu, 2011; Tsui, 2007), the mediating role of power relationships in the process of identity formation. Making use of the CoP theory (Wenger, 1998), one sees that these studies situate identity in a central focus and highlight “the need for teachers to reconstruct their identity to cope with new challenges” (Liu & Xu, 2011, p. 590), such as healthy NNS identities, socio-political identities, teaching methodologies, and top-down policies.

Language Policy

At the national level, Colombia has implemented a language policy within a specific geopolitical context where the major business partners have been the USA and Canada, through the exploitation of mineral resources carried out by multinational companies, the implementation of unbalanced free trade agreements, and the monopolisation of the provision of English (English teacher training and consultancy service for the MEN of other multinationals like The British Council). According to Valencia (2013), this language policy, which intended to make Colombian citizens legitimate participants of the globalised world through the democratization of the use of the English language, has turned into a policy that generates processes of exclusion and stratification through the standardisation and marketing of English. Such an impact on society has directly affected English learners’ and teachers’ identity constructions by setting “asymmetrical power relationships and uneven conditions in English language education” (Escobar, 2013, p. 45). This has also imposed identity shaping discourses. Escobar (2013), in a critical discourse study, analyses the Colombian language policy documents and concurs that the use of discourse strategies has positioned the Colombian ELT CoP in a disadvantageous and vulnerable place.

At an international level, Caihong (2011) has evidenced other identity shaping factors related to language policy. For example, in a university in China, he highlights the powerful influence of policy upon teachers’ identity changes. They are basically concerned with their sense of competence and satisfaction in terms of knowledge, ability to do research, and horizons. The disciplinary nature of college English teaching became a critical factor that affects university EFL teachers’ identity and career development. He states that without the disciplinary nature of college English teaching being recognised, the construction of professionalism in the college English teaching faculty will just be unexplainable. Caihong concluded that “their professional identities are shaped and reshaped in the process of negotiation and balance between personal beliefs and rules at institutional, disciplinary, and public levels” (p. 18).

According to Sharkey (2009) “learning and teaching are always affected by institutional contexts and their policies, ranging from the classroom policies that teachers establish or enact tacitly or explicitly, to the larger rings of policy set by schools, organizations, districts, states, and/or country” (p. 48). In Colombia, for example, the national agenda, Colombia Bilingüe, is the subject of much discussion and debate, raising issues such as: how bilingualism is defined, who is included/excluded in this definition, and how English language proficiency will be determined (González, 2007).

To sum up, the most relevant points highlighted in this section are: the concept of identity as a process of identification with one or several cops; the aspects of identity of members of ELT CoP that are multiple, shifting, and conflicting; and the social nature of the construction or reconstruction of EFL professional identities, which are shaped by economic, cultural, and political factors, especially language policies. All studies reported here have commonalities in the sense that they share a postmodern perspective of identity; they are interested in the processes of EFL teacher identity construction, and they also share the use of qualitative methods to discover, explore, or understand professional identity. In most of the studies, researchers are engaged in investigating through the use of different forms of narratives like autobiographies, diaries, interviews, and reflective journals. The present study followed similar perspectives, constructs, and methodologies.

Method

Interpretative Perspective

The methodological focus of this study is framed within an interpretative perspective of enquiry, particularly the constructivist tradition where reality is constructed, analysed, and regarded critically by the researcher with the help of the participants.

Within the qualitative approach to research, a case study could be defined as a naturalistic inquiry in ontological (a holistic or systemic perspective of the “self” in terms of their experiential understanding, and multiple realities); epistemological (a constructivist orientation to knowledge); methodological (a centrality on interpretation); and axiological (a shared value system of a CoP) terms. This study on teachers’ experiences and beliefs is both qualitative and subjective because it is a shared construction between my participants and me through dialogues and reflections. Creswell (1994) argues that people

seek understanding of the world in which they live and work. They develop subjective meanings of their experience. These meanings are varied and multiple, leading the researcher to look for complexity of views rather than narrowing meanings into a few categories or ideas. (p. 8)

The narrative used either as an autobiographical account or an interview was analysed in broad thematic structures and used details provided by the informants.

Techniques

As mentioned in the literature review, most of the studies (Liu & Xu, 2011; Norton & Early, 2011; Park, 2012; Pavlenko, 2003; Tsui, 2007) used interviews and biographic narratives as data to research teacher identity. Narratives can be defined as “personal and human dimensions of experience over time, and take into account the relationship between individual experience and cultural context” (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000, p. 20). Riessman (2008) says that a narrative is a way of conducting case-centred research. It can be taken from interviews, observation, and documents. “As a general field narrative enquiry is grounded in the study of the particular” (p. 5).

Pavlenko (2007) states that narratives are now widely used to present people’s complex lives, experiences and identities in complex scenarios of multilingual and multicultural communities. Therefore, I also utilised narratives to unveil the human experience, the particular and the sociocultural aspects related to the construction of teacher identities. Since “storytelling happens relationally, collaboratively between speakers and listeners” (Andrews, Squire, & Tamboukou, 2013, p. 201), I reconstructed teachers’ narratives to present them in a holistic manner by selecting, organising, connecting, and evaluating events, experiences, and feelings as meaningful for a particular audience: the teachers themselves.

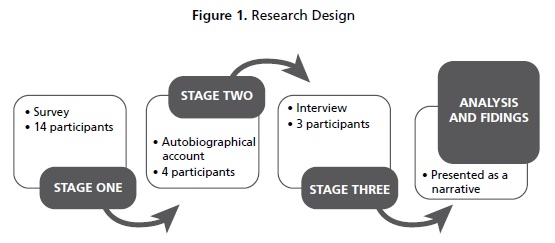

I carried out a three-stage case study and an instrument was used for each stage of the process. At the beginning, 14 out of 20 experienced HS EFL teachers completed a survey designed with some closed questions and a few open questions. It was developed to gather data in the first stage of this study. Its objective was to explore HS EFL teachers’ perceptions of language requirements associated with the NBP.

In thesecond stage, which consisted of writing a narrative or autobiographical account of their language learning process, only four teachers agreed to continue in the study. These four teachers were sent a request to write their language learning biographies as learners and as teachers within the last eight or nine years of the implementation of the NBP. Its purpose was to determine participants’ trajectories as language learners and teachers.

In the third stage, three teachers agreed to participate in an interview to go deep into their perception of the language requirement and how this language policy influenced their identities as learners and as professional language teachers in the past, at present, and in the future.

Participants

I will describe the four participants that remained in the second and third stages. Gloria, who did not participate in the third stage of the study, is an experienced English teacher at a state school. She has had a hard time trying to comply with the requirements of the NBP but has been able to succeed in achieving her goals in spite of her socio-economic background.

Linda is an experienced English teacher at a state school who has struggled to comply with the requirements of the NBP as both learner and practitioner. Although she wanted to study medicine before starting her studies in education, she has developed her identity as a persistent, devoted teacher who slightly disagrees with the language policy but wants to belong to the ELT community.

Mike studied engineering before he decided to become a teacher. He is now an experienced English teacher at a state school. He is a committed practitioner. He has developed his identity as a confident professional who wants to comply with the NBP requirements and trusts educational authorities.

Finally, Stella, who first started studying law, is an experienced English teacher. She strives for professional development and high performance for the benefit of her students. She is critical not only of the language policies but also of the conditions she has to work in, besides being a research conscious practitioner. All of them share the aim of improving ELT education in Colombia.

Data Analysis

The collected data were analysed in a way that the findings obtained in one stage informed the next in order to present the “subject reality” (Pavlenko, 2007, p. 166). The analysis and findings helped to relate the information and to match themes. In this section, the first stage depicts the informants’ contexts, participation in and familiarity with the NBP, their perception of proficiency and determining factors in the identity, and language policy. The second and third stages render the findings that merged out of the thematic analysis, using data from both sources, the autobiographical accounts and the interviews. Figure 1 shows the process followed.

The survey result analysis was based on descriptive statistics that, basically, display the percentages and frequencies through graphs. The analysis of biographical accounts was made based on pre-determined narrative structure: present, past, and future of teachers’ language and professional learning processes. I partially used the phases of thematic analysis suggested by Braun and Clarke (2006) and Saldaña (2013). First, I made myself familiar with the data and generated initial codes across the entire data by using colour coding and side comments. Next, I coded all data so that I was able to find patterns or themes. I followed Saldaña’s (2013) suggestion to use analytic memos to start refining the codes and the themes.

Then, I started searching and reviewing codes that might become prevalent themes in each stage of the study. After that, I defined and named similar themes and selected relevant extracts so that I could produce a report at the end. Final themes, filtered by the researcher’s view and interpretations, are related to the main aims of this study which is framed in the theory of CoP and how shared beliefs reflect the kinship and boundaries of a group. I focused my attention on emerged trends or significant insights that could provide me with evidence of feelings, perceptions, and views of the influence of language policy in teacher identity.

Following the same procedure as with the autobiographies, the interview analysis was made taking into consideration the themes that emerged in the interaction that took place in a semi-structured mode with a few guiding questions. I merged the significant insights gained in the data collection process at my convenience in the findings. Additionally, I presented them in a sequential and meaningful order to re-present, reconstruct, and express informants’ reported experiences, as Andrews et al. (2013) suggest presenting narratives, which go from experience-centred to sociocultural oriented approaches.

Findings

First Stage

Survey

HS teachers were surveyed to characterise the population and to find out about their perception of language requirements associated with the NBP, their own perception of their English level and other aspects of their professional identity.

I sent the survey to 20 ELT master’s candidates who were in their second year at a university in Bogota. I used survey monkey to design, administer, and get the results of the survey. Out of the 20 students, 14 responded, showing a 70% return rate. Based on the answers for Questions 1 to 3, I was able to find out that the informants were all experienced HS teachers who had been teaching English from 9 (nine teachers) to 15 (five teachers) years. Nine female teachers and five male teachers participated in the survey. Out of the 14 teachers, 13 worked at public schools and one worked at a private institution.

The results of Questions 4 and 5 showed there is some familiarity with the NBP and the levels of proficiency established in it, because eight participants said that they were familiar with the language policy, whereas five were not familiar and one did not answer. However, they all managed to rank themselves in the levels of proficiency in English established in the policy and therefore in the NBP. Eleven classified themselves at the B2 level, two at the C1 level, and one at the B1 level, according to the Common European Framework. This might imply that they all are, to a certain extent, familiar with the levels of reference used and required by the language policy and therefore by the NBP.

Question 8 aimed at establishing teachers’ perceptions as legitimate participants in the ELT community in Colombia. Out of 14 teachers, 12 answered they felt they were legitimate users of English based on a screening process they had to go through to become English teachers, their achievements on the International English Language Testing System (IELTS), their knowledge of pedagogy, and the use of a standard variety of English. However, two teachers expressed their feelings of exclusion by saying that “the government says that Colombian teachers are not well prepared in English” (Stella, Survey). This might be because English teachers were questioned about whether their knowledge was at the level needed to carry out the established language policy. Thus, with the legitimacy of their knowledge being questioned, and their promotion and status being affected, these teachers faced a sense of confusion about their professional identity and career development from the very beginning of the implementation of the NBP. Almost ten years later, two teachers still felt that they neither belonged to a community of practice nor were recognised:

I also teach in primary school and I do not have the opportunity to practice my English and as a consequence few people know I am an English teacher. (Linda, Interview)

In Question 9, teachers were asked about their perception of the language requirement. The results showed three positions mainly: one group (five teachers) said that the requirements do not respond to the context and reality of the Colombian society. Another group (five teachers) said that if the government wanted them not only to achieve the required level of English but also to improve their methodology, the MEN should make sure that all teachers get the proper training. The last group (four teachers) expressed their unfamiliarity with the policy and its requirements.

The results of Questions 10 and 11 lend themselves to determine that there was a difference in participants’ self-image as language learners and as professionals because they prioritised language proficiency as learners (eleven teachers), whereas intercultural competence was preponderant in their identity as professionals, even though they regarded language proficiency as an important aspect of their identity. It is interesting how being a non-native speaker was ranked in the lowest position, showing that this condition might not have impacted their identities as language users as much as the other two aspects: language proficiency and intercultural competence.

The last question aimed at identifying other aspects of their identities they considered important as learners and as professionals. They highlighted the following four aspects: professional ethics, personal experiences, previous knowledge, and reflective teaching practice.

To find out more about the results of stage one, second and third stages were set to delve into their personal histories and establish if the language requirement actually had been significant in their trajectories as professional language teachers.

Second Stage

Reported Trajectories

Out of the 14 teachers who completed the survey, I chose four teachers keeping in mindthe following criteria: they all were HS teachers, they had more than ten years’ experience, they answered all the survey questions and they were familiar with the NBP. They were asked to write a language autobiography and to sign a consent form. In the autobiographies, three pre-categories were set up from the beginning, indicating one trajectory as a language learner, another trajectory as a language teacher, and the other future trajectory or imagined future within a new language policy in Colombia. It is necessary to mention that only four teachers handed in their autobiographical accounts.

Trajectories as language learners. Language requirement might have affected teachers’ language learning experience because the four participants did different things to improve their level of English while studying for their undergraduate degree. However, not one mentioned the international language test results as a proof of their proficiency level in English in their autobiographies or interviews, although they were aware of their existence. One reason could be that the access to international tests is very limited for the EFL teachers and their cost is too high for the EFL community in Colombia. They all mentioned they wanted to improve their level of English proficiency to work abroad, pursue their studies at a master’s level, or improve their teaching practice. They seemed to be more concerned about their own qualification and their students’ improvement than they were about international standards, globalisation, or internationalisation. This might indicate that either the language policy had not reached the target population or the HS EFL community of teachers had not appropriated it thoroughly.

Consequently, this might indicate that the language requirement established by the external authorities does not coincide with the boundaries established by the internal CoP (Colombian ELT community). The participants can assign a different value to these language requirements, which do not relate to their proximate context. Teachers perceived them as alien elements that did not determine their belonging to the EFL CoP. They would rather take the chance to learn from others (partners and teachers) to improve their level of English proficiency and receive feedback from colleagues or more knowledgeable people. However, in the first stage, the role of language proficiency was seen as highly determining in their identity.

Participants’ current professional learning. Reporting on their present state, teachers were aware of the complex realities of their EFL classrooms. They were positioned in their role and responsibility as English language teachers. Moreover, they had become critical of educational policies and were willing to participate in their implementation, despite their hard teaching conditions, students’ lives in their communities and limitations implicated in the context. They worked towards a higher educational status by studying for a graduate degree at the same university to provide their students with a better quality of education as evidenced in Stella’s and Gloria’s written account.

At this stage, although they all also showed willingness to reach the objectives established by the different programmes or policies established by the MEN, their professional identity started shifting from the fixed conception of language proficiency to other defining aspects of their professional identity such as: awareness of context and limitation of working conditions, as Mike and Linda stated in their narratives.

Participants’ imagined future. The participants looked forward to completing their graduate studies to become better practitioners by “changing paradigms in English language teaching and using new methodologies to bring better opportunities to learners” (Gloria, Autobiography). They knew that their professional development was a social responsibility besides being a personal goal. One of them wanted to become a professor at the university level even though she knew that this would require a lot of investment and effort to achieve (Linda, Interview). Another teacher wanted to continue her professional development as far as English improvement and methodology were concerned (Stella, Autobiography). The other teacher would like to continue contributing to the consolidation of foreign language policy to the best of his abilities (Mike, Interview).

As we can see, professional identity has evolved throughout their trajectories but, consciously or unconsciously, teachers have been affected by the language policy in the last ten years of its implementation. What is more, the theme of achieving a high level of language proficiency is pervasive in their narratives.

Third Stage

Only three of my initial participants (Stella, Linda, and Mike) were willing to get to this stage where they were interview by me. I used the information collected throughout the study focusing on viewpoints regarding language requirement associated with the NBP and positive and negative feelings the teachers had about the impact of the language requirements of the NBP.

Challenge, achievement, hope, and expectancy are some of the positive feelings teachers had about the NBP and its requirement for teachers.

I think it [the C1 in the IELTS] is the confirmation that I know and that gives me kind of security of what I am doing in the classroom, and actually my students feel secure with me in the classroom. (Stella, Interview)

However, they also held negative feelings such as limitations, frustrations, scepticism, and disappointment towards the foreign language policy defined by the MEN and its pertinence. They express these views in their interviews and autobiographies as follows:

Students do not have food to prepare their breakfast, lunch, or dinner. They do not have money to buy a notebook or a pencil, and they suffer family violence, among others. And I as a teacher should face those situations, trying to engage students in the class, telling [them] they have to know that English is important for them. (Linda, Autobiography)

I know C1 is kind of difficult to find in public schools in English teachers, the problem is that when we learned, . . . English, we wanted to travel, we wanted to go out, we wanted to do so many things instead of ending up in a public (state) institution . . . So many good teachers, in terms of English level proficiency, travel or work in different private institutions that are demanding good teachers and the payment is much better, so public institutions lack of good teaching because of that reason. (Mike, Interview)

As we can see, there are different opinions and feelings about the language policy. They depend on the context in which teachers work, their views on language education, and their awareness of students’ environment in relation to the policy. In these extracts identity is reflected in a dynamic and conflicting way since teachers feel satisfied when complying with the language requirement but at the same time, they know the circumstances are not ideal for them or their students to achieve the desired standards.

Regarding teachers’ views of language policy and therefore NBP, Mike seemed to have internalised the mainstream discourses and made them part of his identity:

They [policies] should have affected in my life, in my teaching practice because I follow them, I’ve read some of them, I’m not a really good reader unfortunately, and sometimes I avoid getting into politics and things, I feel that it is a kind of a pressure, . . . their policies, and I read what they want us to do and they want the students to achieve, and I think that they are good...everything that the government does is supposed to be good for people, and this is not an exception. This is supposed to be good. (Mike, Interview)

Whereas, the others were very critical of the language requirements and the pertinence of the foreign language policy, as presented by the informants:

Bilingualism programs presented by the government with any name or in period of time, are so far from the realities that exist in our schools and aim to eventually submit annual statistics which in my opinion are far from the education of our learners. (Gloria, Autobiography)

Up today, sixth, seventh, and eighth graders have three hour of class per week, and ninth to eleventh graders have four. The policies and governmental projects look for bilingualism process in Colombia by 2025; nevertheless, I do not see how it can be a reality with such a reduced exposure to the foreign language. (Stella, Autobiography)

Due to paper extension constraints, I used only Linda because I found her narratives to be representative of most HS EFL teachers’ “life realities” (Pavlenko, 2007). I selected, organised, and put together the narratives of autobiographies and interviews and briefly narrated Linda’s construction and reconstruction of her professional identity within the historical, social, and political complexities of her context (see Appendix).

Reflection and Conclusion

This study has offered a critical interpretive account of mainly threeteachers that engaged in the whole process. It has been concerned with a critical perspective of a language policy from the people that bear its implementation. It has also contributed new aspects to the understanding of the construction of teacher identity in a particular socioeconomic context in five ways.

First, being an English teacher was not the first choice of the informants who are now committed educators, showing that identity is dynamic. This agrees with Varghese et al.’s (2005) view of identity.

Second, teachers knew about the language policies and language requirements but most of them didnot feel that they had access to opportunities for development, demonstrating that power relations shape identity, which concurs with the views of Liu and Xu (2011) in their study of inclusion and exclusion of language teachers.

Third, feelings towards the English language requirements demonstrated to be conflicting factors influencing teachers’ construction and reconstruction of their identities. The subject matter (English) is an essential part of their identities, but their identity is not limited to their subject matter. There were many other external and internal factors that influenced teachers’ professional identity as members of the EFL CoP, confirming that identity is multifaceted. This agrees with the viewpoint of Norton and Early (2011) and Glass (2012).

Fourth, teachers’ trajectories have changed their identities throughout their lives but this change, to my view, has been exerted by the language policy, rendering how external circulating discourses percolate local identities. This view is also expressed by Valencia (2013) when he refers to the discourses of bilingualism in Colombia. Finally, foreign language policy in Colombia does not only have a negative side as regarded by the local ELT experts, but it also contributes positively to the teachers’ development and achievement, even though it has been implemented in a managerial perspective of professionalism.

In addition, the implementation of a top-down foreign language policy in Colombia through the NBP has entailed, for teachers, a change or a reconstruction in identity as language learners as well as professional language teachers. Based on the gathered data and my interaction with the teachers and their narratives, the policy has also encouraged them to become better language users and reflective practitioners and therefore better language teachers with or without the help of the authorities. They have evolved from being a below average language learner to becoming well prepared, well-informed, and critical professional language teachers.

Linda, Gloria, Stella, and Mike might represent the majority of English teachers in urban areas in Colombia. They have struggled to get an education, strived for improvement and succeededin becoming professional English teachers in spite of many barriers, lack of access and social recognition, and discriminatory policies. They have walked us through their identity construction as a life-long learning experience.

References

Andrews, M., Squire, C., & Tamboukou, M. (Eds.). (2013). Doing narrative research. Los Angeles, US: Sage. http://doi.org/10.4135/9781526402271.

Beijaard, D. (1995). Teachers’ prior experiences and actual perceptions of professional identity. Teachers and Teaching, 1(2), 281-294. http://doi.org/10.1080/1354060950010209.

Blackledge, A. (2002). The discursive construction of national identity in multilingual Britain. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education, 1(1), 67-87. http://doi.org/10.1207/S15327701JLIE0101_5.

Block, D. (2006). Multilingual identities in a global city: London stories. London, UK: Palgrave. http://doi.org/10.1057/9780230501393.

Borg, S. (2006). Teacher cognition and language education: Research and practice. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. http://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Caihong, H. (2011). Changes and characteristics of EFL teachers’ professional identity: The cases of nine university teachers. Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics, 34(1), 3-21. http://doi.org/10.1515/cjal.2011.001.

Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. San Francisco, US: Jossey-Bass.

Creswell, J. W. (1994). Research design: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks, US: Sage.

Day, C. (2004). Change agendas: The roles of teacher educators. Teaching Education, 15(2), 145-158. http://doi.org/10.1080/1047621042000213584.

de Mejía, A.-M. (2006). Bilingual education in Colombia: Towards a recognition of languages, cultures and identities. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 8, 152-168.

Duff, P. A., & Uchida, Y. (1997). The negotiation of teachers’ sociocultural identities and practices in postsecondary EFL classrooms. TESOL Quarterly, 31(3), 451-486. http://doi.org/10.2307/3587834.

Escobar, W. Y. (2013). Identity-forming discourses: A critical discourse analysis on policy making processes concerning English language teaching in Colombia. PROFILE Issues in Teachers Professional Development, 15(1), 45-60.

Glass, K. (2012). Teaching English in Chile: A study of teacher perceptions of their professional identity, student motivation, and pertinent learning contents. Frankfurt, DE: Peter Lang.

González, A. (2007). Professional development of EFL teachers in Colombia: Between colonial and local practices. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 12(18), 309-331.

Jenkins, J. (2005). Implementing an international approach to English pronunciation: The role of teacher attitudes and identity. TESOL Quarterly, 39(3), 535-543. http://doi.org/10.2307/3588493.

Liebkind, K. (2010). Social psychology. In J. A. Fishman & O. García (Eds.), Handbook of language and ethnic identity: Disciplinary and regional perspectives (Vol. 1, 2nd ed., pp. 18-31). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Liu, Y., & Xu, Y. (2011). Inclusion or exclusion?: A narrative inquiry of a language teacher’s identity experience in the ‘new work order’ of competing pedagogies. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(3), 589-597. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.10.013.

Menard-Warwick, J. (2008). The cultural and intercultural identities of transnational English teachers: Two case studies from the Americas. TESOL Quarterly, 42(4), 617-640. http://doi.org/10.1002/j.1545-7249.2008.tb00151.x.

Norton, B. (1997). Language, identity, and the ownership of English. TESOL Quarterly, 31(3), 409-429. http://doi.org/10.2307/3587831.

Norton, B. (2000). Identity and language learning: Gender, ethnicity, and educational change. Harlow, UK: Pearson.

Norton, B., & Early, M. (2011). Researcher identity, narrative inquiry, and language teaching research. TESOL Quarterly, 45(3), 415-439.

Park, G. (2012). “I am never afraid of being recognized as an nnes”: One teacher’s journey in claiming and embracing her non-native-speaker identity. TESOL Quarterly, 46(1), 127-151. http://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.4.

Pavlenko, A. (2003). “I never knew I was a bilingual”: Reimagining teacher identities in TESOL. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education, 2(4), 251-268. http://doi.org/10.1207/S15327701JLIE0204_2.

Pavlenko, A. (2007). Autobiographic narratives as data in applied linguistics. Applied Linguistics, 28(2), 163-188. http://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amm008.

Pavlenko, A., & Blackledge, A. (Eds.). (2004). Negotiation of identities in multilingual contexts (Vol. 45). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Los Angeles, US: Sage.

Saldaña, J. (2013). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, US: Sage.

Sharkey, J. (2009). Imbalanced literacy: How a us national educational policy has affected English learners and their teachers. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 11, 48-62.

Tsui, A. B. M. (2007). Complexities of identity formation: A narrative inquiry of an EFL teacher. TESOL Quarterly, 41(4), 657-680. http://doi.org/10.1002/j.1545-7249.2007.tb00098.x.

Valencia, M. (2013). Language policy and the manufacturing of consent for foreign intervention in Colombia. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 15(1), 27-43.

Varghese, M., Morgan, B., Johnston, B., & Johnson, K. A. (2005). Theorizing language teacher identity: Three perspectives and beyond. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education, 4(1), 21-44. http://doi.org/10.1207/s15327701jlie0401_2.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511803932.

Wenger, E. (2000). Communities of practice and social learning systems. Organization, 7(2), 225-246. http://doi.org/10.1177/135050840072002.

Wenger, E. (2010). Communities of practice and social learning systems: The career of a concept. In C. Blackmore (Ed.), Social learning systems and communities of practice (pp. 179-198). London, UK: Springer. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-84996-133-2_11.

About the Author

Julio César Torres-Rocha is a teacher educator at Universidad Libre (Colombia) and currently a Doctoral Candidate in Education (TESOL) at University of Exeter, UK. He holds an MA in Research Methods in Applied Linguistics and ELT from Warwick University (UK) and an MA in Applied Linguistics to TEFL from Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas (Colombia).

Linda defines herself as an experienced English teacher at a state school who has struggled to comply with the requirement of the NBP and evolves from a weak language learner to a responsible and informed EFL practitioner. She has developed her identity as a persistent, devoted teacher/guide who slightly disagrees with the language policy but wants to belong to the Colombian ELT community.

Tracing Linda’s answers from the beginning of this study from the survey and autobiography to the stage of interviewing, I found that she did not want to become an English teacher; instead, she wanted to study medicine, but due to financial reasons she ended up enrolling in a professional teaching programme at a state university in Bogota. She said she was not cut out for English but after sorting out health and family problems, investing long hours in studying with the help of more knowledgeable partners, she was able to reach an acceptable communicative competence that allowed her to graduate as an English teacher.

At this moment, she identifies herself as an English teacher although she still feels unrecognised as a legitimate participant in her community because her work has been not only in high school but also in primary school. Primary school teachers in this context are teachers who have to teach English without being specialists even though this is not Linda’s case now because she holds a BA in Education majoring in English. She did not feel very confident with her language proficiency and since she started to study for her degree, she had always been looking for opportunities to improve her level of English.

After finishing her undergraduate studies, she started to work in the private sector; however, only after more than 8 years working there did she manage to pass the screening process to work in the public or state sector. She has been working in a government-funded school for 4 years, even though she had already worked for a long time in the private sector. Currently she is pursuing her graduate studies at a private university in the area of English didactics.

References

Andrews, M., Squire, C., & Tamboukou, M. (Eds.). (2013). Doing narrative research. Los Angeles, US: Sage. http://doi.org/10.4135/9781526402271.

Beijaard, D. (1995). Teachers’ prior experiences and actual perceptions of professional identity. Teachers and Teaching, 1(2), 281-294. http://doi.org/10.1080/1354060950010209.

Blackledge, A. (2002). The discursive construction of national identity in multilingual Britain. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education, 1(1), 67-87. http://doi.org/10.1207/S15327701JLIE0101_5.

Block, D. (2006). Multilingual identities in a global city: London stories. London, UK: Palgrave. http://doi.org/10.1057/9780230501393.

Borg, S. (2006). Teacher cognition and language education: Research and practice. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. http://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Caihong, H. (2011). Changes and characteristics of EFL teachers’ professional identity: The cases of nine university teachers. Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics, 34(1), 3-21. http://doi.org/10.1515/cjal.2011.001.

Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. San Francisco, US: Jossey-Bass.

Creswell, J. W. (1994). Research design: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks, US: Sage.

Day, C. (2004). Change agendas: The roles of teacher educators. Teaching Education, 15(2), 145-158. http://doi.org/10.1080/1047621042000213584.

de Mejía, A.-M. (2006). Bilingual education in Colombia: Towards a recognition of languages, cultures and identities. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 8, 152-168.

Duff, P. A., & Uchida, Y. (1997). The negotiation of teachers’ sociocultural identities and practices in postsecondary EFL classrooms. TESOL Quarterly, 31(3), 451-486. http://doi.org/10.2307/3587834.

Escobar, W. Y. (2013). Identity-forming discourses: A critical discourse analysis on policy making processes concerning English language teaching in Colombia. PROFILE Issues in Teachers Professional Development, 15(1), 45-60.

Glass, K. (2012). Teaching English in Chile: A study of teacher perceptions of their professional identity, student motivation, and pertinent learning contents. Frankfurt, DE: Peter Lang.

González, A. (2007). Professional development of EFL teachers in Colombia: Between colonial and local practices. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 12(18), 309-331.

Jenkins, J. (2005). Implementing an international approach to English pronunciation: The role of teacher attitudes and identity. TESOL Quarterly, 39(3), 535-543. http://doi.org/10.2307/3588493.

Liebkind, K. (2010). Social psychology. In J. A. Fishman & O. García (Eds.), Handbook of language and ethnic identity: Disciplinary and regional perspectives (Vol. 1, 2nd ed., pp. 18-31). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Liu, Y., & Xu, Y. (2011). Inclusion or exclusion?: A narrative inquiry of a language teacher’s identity experience in the ‘new work order’ of competing pedagogies. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(3), 589-597. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.10.013.

Menard-Warwick, J. (2008). The cultural and intercultural identities of transnational English teachers: Two case studies from the Americas. TESOL Quarterly, 42(4), 617-640. http://doi.org/10.1002/j.1545-7249.2008.tb00151.x.

Norton, B. (1997). Language, identity, and the ownership of English. TESOL Quarterly, 31(3), 409-429. http://doi.org/10.2307/3587831.

Norton, B. (2000). Identity and language learning: Gender, ethnicity, and educational change. Harlow, UK: Pearson.

Norton, B., & Early, M. (2011). Researcher identity, narrative inquiry, and language teaching research. TESOL Quarterly, 45(3), 415-439.

Park, G. (2012). “I am never afraid of being recognized as an nnes”: One teacher’s journey in claiming and embracing her non-native-speaker identity. TESOL Quarterly, 46(1), 127-151. http://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.4.

Pavlenko, A. (2003). “I never knew I was a bilingual”: Reimagining teacher identities in TESOL. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education, 2(4), 251-268. http://doi.org/10.1207/S15327701JLIE0204_2.

Pavlenko, A. (2007). Autobiographic narratives as data in applied linguistics. Applied Linguistics, 28(2), 163-188. http://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amm008.

Pavlenko, A., & Blackledge, A. (Eds.). (2004). Negotiation of identities in multilingual contexts (Vol. 45). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Los Angeles, US: Sage.

Saldaña, J. (2013). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, US: Sage.

Sharkey, J. (2009). Imbalanced literacy: How a us national educational policy has affected English learners and their teachers. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 11, 48-62.

Tsui, A. B. M. (2007). Complexities of identity formation: A narrative inquiry of an EFL teacher. TESOL Quarterly, 41(4), 657-680. http://doi.org/10.1002/j.1545-7249.2007.tb00098.x.

Valencia, M. (2013). Language policy and the manufacturing of consent for foreign intervention in Colombia. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 15(1), 27-43.

Varghese, M., Morgan, B., Johnston, B., & Johnson, K. A. (2005). Theorizing language teacher identity: Three perspectives and beyond. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education, 4(1), 21-44. http://doi.org/10.1207/s15327701jlie0401_2.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511803932.

Wenger, E. (2000). Communities of practice and social learning systems. Organization, 7(2), 225-246. http://doi.org/10.1177/135050840072002.

Wenger, E. (2010). Communities of practice and social learning systems: The career of a concept. In C. Blackmore (Ed.), Social learning systems and communities of practice (pp. 179-198). London, UK: Springer. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-84996-133-2_11.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Lina Betancurt, Liliana del Pilar Gallego. (2025). An Integrative Literature Review on English Teachers as Agents of Change. Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 27(1), p.191. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v27n1.113092.

2. Reinelio Morales Llano. (2022). Política lingüística, bilingüismo y rol del maestro de inglés: una revisión desde el entorno global al contexto colombiano. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 24(2) https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.18130.

3. Jhon Eduardo Mosquera Pérez. (2022). CLIL in Colombia: Challenges and Opportunities for its Implementation.. GIST – Education and Learning Research Journal, 24, p.7. https://doi.org/10.26817/16925777.1347.

4. José V. Abad, Jennifer Daniela Regalado Chicaiza, Isabel Cristina Acevedo Tangarife. (2023). Pedagogical Relationships and Identities in Research Incubators: Reconceptualizing Research Training for Language Teachers. Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 25(1), p.17. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v25n1.94333.

5. Lucía Belmonte Carrasco, Guadalupe De la Maya Retamar. (2023). Emotions of CLIL Preservice Teachers in Teaching Non-Linguistic Subjects in English. Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 25(2), p.185. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v25n2.103916.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

Copyright (c) 2017 PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.