The Effect of Pecha Kucha Presentations on Students’ English Public Speaking Anxiety

Los efectos de presentaciones “Pecha Kucha” sobre la ansiedad a hablar en público de estudiantes de inglés

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n_sup1.68495Keywords:

English as a foreign language, Pecha Kucha, speaking anxiety (en)ansiedad del habla, inglés como lengua extranjera, Pecha Kucha (es)

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n_sup1.68495

The Effect of Pecha Kucha Presentations on Students’ English Public Speaking Anxiety

Los efectos de presentaciones “Pecha Kucha” sobre la ansiedad a hablar en público de estudiantes de inglés

Abdullah Coskun*

Abant Izzet Baysal University, Bolu, Turkey

This article was received on September 10, 2017, and accepted on November 7, 2017.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Coskun, A. (2017). The effect of Pecha Kucha presentations on students’ English public speaking anxiety. Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 19(Suppl. 1), 11-22. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n_sup1.68495.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

The objective of this study is to investigate the effect of the Pecha Kucha presentation format on English as foreign language learners’ public speaking anxiety. The participants were 49 students in the English Translation and Interpretation Department of a state university in Turkey. A pre- and post-test experimental research design was used in this study. Students were given a questionnaire as the pre-test prior to the preparation of their presentations and as the post-test immediately following the presentation in the classroom. According to the paired samples statistics, students’ English public speaking anxiety was reduced significantly as a result of their experience using the Pecha Kucha presentation format. It was concluded that this presentation format can be incorporated into the English as a Foreign Language classroom.

Key words: English as a foreign language, Pecha Kucha, speaking anxiety.

El objetivo de este estudio es investigar el efecto del formato de presentación de Pecha Kucha en la ansiedad al hablar en público de estudiantes de inglés como lengua extranjera. Los participantes fueron 49 estudiantes del Departamento de Traducción e Interpretación en Inglés de una universidad estatal en Turquía. Se utilizó un diseño de investigación experimental previo y posterior al ensayo. Los estudiantes recibieron un cuestionario antes de la preparación de sus presentaciones e inmediatamente después de la presentación en el aula. De acuerdo con los resultados, la ansiedad de hablar en inglés de los estudiantes se redujo significativamente como resultado de su experiencia usando el formato de presentación de Pecha Kucha. Se concluye que este formato de presentación puede ser incorporado en el salón de clases de inglés.

Palabras clave: ansiedad del habla, inglés como lengua extranjera, Pecha Kucha.

Introduction

It is important for university students to search for a particular topic, interpret the content they find, and organize it in the form of an oral presentation (García-Laborda, 2013; García-Laborda & Litzler, 2015). These skills are expected not only to enable students to organize knowledge, but also to improve their public speaking skills. Because skills such as presenting ideas in a systematic way and speaking effectively to an audience are necessary for university graduates (Artyushina, Sheypak, & Khovrin, 2010; García-Laborda & Litzler, 2017), oral presentation has been the main focus of various courses at the university level.

As suggested by Murugaiah (2016), the most common way to present content verbally is to use Microsoft Office PowerPoint. However, according to her observation, a number of issues might weaken the quality of students’ presentations, such as not concentrating on main points, reading from wordy slides, and overrunning the allocated time. Therefore, she argues that students should be encouraged to use the PowerPoint software more creatively. As an alternative to the time-consuming traditional presentations with text-heavy slides, Pecha Kucha (PK) has emerged as a result of the creative use of PowerPoint software (Klentzin, Paladino, Johnston, & Devine, 2010; Robinson, 2015).

Devised by two architects, Astrid Klein and Mark Dytham, PK is actually a Japanese term for the sound of “chit chat”. Although chit-chat is an informal talk, the originators of the idea seem to use the term ironically as they developed PK as an alternative to long, wordy, and boring PowerPoint presentations often neglecting the use of images (Lucas & Rawlins, 2015). According to the official website (http://www.pechakucha.org/), PK requires the presentation of 20 slides, each of which can be displayed for 20 seconds. That is the reason why this fast-paced presentation style is also called “20x20” on its website. The rationale behind PK is to enable the speaker to present ideas by using images in an allocated time of six minutes and 40 seconds. Pointing out that PK is a highly visual presentation style, Christianson and Payne (2011) highlight that the slides in a PK presentation must automatically run with a timer as time is the most critical aspect of this presentation format.

Even though PK was originally created as a public speaking technique to capture architects’ attention, its popularity went beyond the field of architecture and spread quickly to other disciplines as a novel means of presentation (Tomsett & Shaw, 2014). “PK nights” have also become popular around the world as a way of presenting a piece of work and sharing opinions related to a public issue (Snow, 2006). Moreover, PK is currently utilized frequently in the classroom (Foyle & Childress, 2015) as it offers many benefits within the education sphere. Despite some of the drawbacks, such as presenting within a certain period of time and the inflexible nature and selection of visuals for each slide (Christianson & Payne, 2011); advantages of the PK presentation style outweigh its disadvantages.

One of the greatest advantages of PK is that it is often very appealing, engaging, and enjoyable to the audience (Christianson & Payne, 2011; Nguyen, 2015; Shiobara, 2015; Soto-Caban, Selvi, & Avila-Medina, 2011). According to A. M. Beyer (2011), the creative use of PowerPoint software has the potential to result in high student engagement on the side of both the presenter and the audience. In another study, it was found that PK is far more effective in terms of students’ explaining skills than the traditional presentation format (Widyaningrum, 2016). In addition to its engaging nature, it is emphasized that through PK presentations, students can learn how to create visually attractive slides (Shiobara, 2015).

The time constraint in the PK presentation style is often regarded as a benefit rather than a drawback. Reynolds (2012) illustrated the time limitation in PK as an advantage with a thought-provoking question: “Which would be more difficult for a student and a better indication of their knowledge: a 45-minute recycled and typical PowerPoint presentation or a tight 6:40 presentation followed by questions and discussion?” (p. 41). In a similar vein, it is stated that PK requires students to practice and rehearse for a long time in order to remain within the allocated time during the presentation, which reduces the mistakes often encountered during traditional presentations (A. A. Beyer, Gaze, & Lazicki, 2012).

Especially in terms of learning and teaching English as a foreign/second language (EFL/ESL), the PK presentation style offers many opportunities. First of all, it has been pointed out that PK improves students’ speaking and oral presentation skills (Nguyen, 2015; Shiobara, 2015). The PK presentation format is also believed to pave the way for English language students to think about the linguistic, paralinguistic, as well as technological dimensions of the presentation (Artyushina et al., 2010). Likewise, Baker (2014) maintains that the presenters can achieve the automaticity and speak more confidently as a result of the PK experience as such presentations necessitate a lot of rehearsal for the presenter to properly manage the allocated time. Additionally, Baskara (2015) found that students who made PK presentations became more autonomous in structuring their ideas and were more active in the language learning process. An added benefit of integrating PKs into the language classroom is leading students to improve their information and communications technology (ICT) skills (Mabuan, 2016a). On the other hand, Ryan (2012) revealed that using PKs can help EFL students improve their pronunciation by enabling them to produce natural speech to keep up with the tempo of the presentation style. Last but not least, as Michaud (2015) emphasizes, PKs provide EFL students with an opportunity to be creative and to make presentations on topics they are passionate about.

In addition to the above-mentioned advantages of PKs in the EFL classroom, the researcher aims to explore whether this presentation style has an effect on students’ English public speaking anxiety.

Public Speaking Anxiety

In general terms, foreign language classroom anxiety is described as “a distinct complex of self-perceptions, beliefs, feelings, and behaviors related to classroom language learning arising from the uniqueness of the language learning process” (Horwitz, Horwitz, & Cope, 1986, p. 128). According to the literature, anxiety in the foreign language learning process can emerge as facilitative or debilitative anxiety. From Scovel’s (1978) perspective, facilitative anxiety enables students to challenge the new task and leads them to the approval behavior; however, debilitative anxiety makes students avoid the new task by causing them to develop avoidance behavior. From this explanation, it is realized that facilitative anxiety motivates students to perform a task more efficiently by spending effort in coping with anxiety; in contrast, debilitative anxiety is considered an extreme level of anxiety affecting their performance negatively (Simpson, Parker, & Harrison, 1995).

Among the four basic foreign language skills, speaking is the skill causing the highest level of anxiety (Cheng, Horwitz, & Schallert, 1999; Young, 1990). In other words, when students have to speak a foreign language, they are generally afraid of doing so. This common phenomenon experienced by the person who is afraid to make a speech is described as public speaking anxiety (Ayres & Hopf, 1993), and the fear of speaking in public is known as glossophobia. It is assumed that approximately 85% of speakers feel anxious before presenting a speech in their native languages (Burnley, Cross, & Spanos, 1993). This statistic must be even higher when it comes to foreign language public speaking anxiety.

McCroskey (1970) divides public speaking anxiety into four basic stages: pre-preparation anxiety, preparation anxiety, pre-performance anxiety, and performance anxiety. Plangkham and Porkaew (2012) explain that pre-preparation anxiety is an issue when a student knows that he/she will make a public speech soon; preparation anxiety becomes apparent when a student begins to prepare for a speech; pre-performance anxiety comes forth when a speaker rehearses the speech; and finally, performance anxiety appears while a student is making the public speech.

It is argued in the literature that although English language teachers make a lot of effort to develop students’ English public speaking skills, the problem of public speaking anxiety is known to be an obstacle to many students (Ciarrocca & Brown, 2015). Public speaking anxiety both in our first language and in a second/foreign language usually appears when speakers think that their performance could be erroneous or not comprehensible (Brown, 2000). Lack of fluency in the target foreign language could be another reason why some students experience public speaking anxiety (Beatty & Friedland, 1990).

Therefore, it is suggested that English language teachers ought to be aware of public speaking anxiety and develop strategies to encourage their students to deal with it (Ciarrocca & Brown, 2015). One way to reduce public speaking anxiety is to enable students to practice speech through repetition and rehearsal (Liao, 2014). According to many researchers, PK is one of the presentation styles enabling students to practice speech, and thus lowering their English public speaking anxiety (Swathipatnaik & Davidson, 2016). Lucas and Rawlins (2015) also found in their study that PK helped students handle public speaking anxiety by focusing on “how short a time they have for each slide instead of thinking about how long they have to talk” (p. 106). Specifically for the language classroom, PK is believed to lead students to feel that the presentation is short enough to accomplish, which motivates them to spend more time practicing and rehearsing PK presentations than they do for traditional presentations (Shiobara, 2015). It is likely for students to lower their public speaking anxiety after several rehearsals for their presentations.

In a similar vein, it was found in a study that students who were involved in PK presentations scored significantly higher in English public speaking performance than the students who had traditional speaking lessons (Zharkynbekova, Zhussupova, & Suleimenova, 2017). In addition, Tomsett and Shaw (2014) uncovered that PKs can be used by language learners as a way of presenting content to help cope with the fear of speaking English in class. This finding was also echoed by Mabuan (2016b) who came to the conclusion that PK presentations not only help students practice their English speaking skills but also increase their confidence while reducing their public speaking anxiety. On the other hand, Sylvan Payne, who is an expert on PK presentation format, gives the following example to illustrate the positive influence of PKs on students’ English public speaking anxiety (Personal Communication, July 10, 2017):

The PK adrenaline rush is normal and can be a positive thing if you channel it. And the best way to do so is through practice. I had a student recently who had been in the army and he compared it to combat training. Once the bell rings and the presentation starts, if you’ve practiced enough, the training kicks in and you’re okay. And once you’ve been in combat once—or done a presentation—and survived, you know next time you’ll probably be okay. And you appreciate that you’ve practiced.

Considering the benefits of PKs for the EFL classroom and the assumption that it might reduce students’ public speaking anxiety, this study is an attempt to integrate the PK presentation format into EFL speaking-based courses offered to English translation and interpretation students in a state university in Turkey and to assess the effect of this presentation format on students’ English public speaking anxiety.

Need for the Study

Although studies regarding the PK presentation format have been carried out in different parts of the world and have yielded promising findings about its use in learning and teaching English, the researcher has not come across any single paper focusing on PK in the Turkish EFL context. Also, reviewed studies dealing with PK generally concentrate on students’ opinions about this presentation format, and their opinions have been obtained mostly through questionnaires or interviews. As no studies regarding the effect of PKs on students’ English public speaking anxiety have been carried out, this study aims to delve into this issue by means of a pre- and post-test experimental research design to bridge the gap in the existing literature.

Additionally, participants of this study regularly prepare English presentations in line with the objectives of the English speaking-based courses in the research context. However, it was observed that their presentations were often dominated by long sentences which were generally read out loud. When such presentations were wordy, lacked images, and were too long; listeners were observed feeling bored or uninterested. For that reason, PK was integrated into the speaking-based courses to attract listeners’ attention, as well as to assess the effectiveness of PK from students’ perspectives. As PK was a brand-new idea in the context of the present study, some students were observed feeling very anxious when they first heard of the PK presentation style. Therefore, it is a key concern for the researcher to dwell on the effect of PK on students’ English public speaking anxiety.

Furthermore, as speaking anxiety is one of the major concerns in the Turkish EFL context (Öztürk & Gürbüz, 2014; Tok, 2009), it is deemed necessary to find novel ways to reduce students’ English speaking anxiety. Consequently, the current study intends to explore whether PK can reduce Turkish EFL students’ public speaking anxiety as an alternative presentation technique. More specifically, the researcher aims to seek an answer to the following research question: “What is the effect of Pecha Kucha presentation format on students’ English public speaking anxiety?”

Method

In this study, a pre- and post-test experimental research design was used. Participants completed a questionnaire related to public speaking anxiety as the pre-test before they started preparing their PKs. After they presented their PKs, they filled out the same questionnaire as the post-test to explore the effect of the PK presentation format on their English public speaking anxiety level.

Participants

Participants were 49 upper-intermediate freshman, sophomore, and junior English translation and interpretation students taking English speaking-based courses (e.g., Speaking Skills in English) in a Turkish university. As the department is new, it does not have senior students, and students whose presentations were not prepared in accordance with the PK presentation format were excluded from the study.

Data Collection Instrument

To find out participants’ level of public speaking anxiety, a questionnaire was used in this study as the pre-test and post-test. The questionnaire in English was developed by Plangkham and Porkaew (2012) who adapted the Personal Report of Public Speaking Anxiety designed by McCroskey (1970). The questionnaire includes 16 five-point Likert scale items concerning four stages of public speaking which make up the following sub-dimensions in the questionnaire: pre-preparation (e.g., I feel tense when I see the words “speech” and “public speech” on a course outline when studying), preparation (e.g., While preparing to give a speech, I feel tense and nervous), pre-performance (e.g., I feel anxious while rehearsing a speech), and performance (e.g., My hands shake and some parts of my body feel very tense when I am delivering a speech). Related to each sub-dimension, there are four items rated on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) response scale. According to this rating, as the agreement level with the items increases, participants’ anxiety level also increases.

For validity and reliability concerns, the questionnaire was piloted by Plangkham and Porkaew (2012) for the Thai EFL context. For its validity in the Turkish EFL context, it was also sent out for review to an assessment and evaluation expert as well as a foreign language teaching expert. Also, five students who did not take part in this study gave feedback about the difficulty level of the items. No changes were deemed necessary for the original questionnaire. According to the pre-test results, the questionnaire was found to be reliable in this study with a Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient of .91. For the pre-preparation, preparation, pre-performance, and performance sub-dimensions, the following Cronbach’s alpha values were found respectively: .85, .69, .67, and .85.

Procedure and Data Collection

All the students who took part in this study had made traditional PowerPoint presentations earlier in speaking-based courses in the context of this study. Therefore, they were already familiar with using Microsoft Office PowerPoint. For this study, they were trained for two weeks (a total of six hours) on the guiding principles of the PK presentation format. The definition and the historical background of PK, its advantages and basic rules (e.g., the number of slides, timing of each slide, and the importance of presenting the content through images) were explained to the participants. During the training, students were shown the “Pecha Kucha Rubric” developed by Holliday (2013) to familiarize them with the requirements of a good PK presentation.

In addition, two PK examples retrieved from the official website of Pecha Kucha (http://www.pechakucha.org) were demonstrated to make students aware of the conventions of pk. Finally, the 20x20 PowerPoint template developed by Christianson and Payne (2011) was provided to the students so that they could prepare 20 slides, each of which would be shown for 20 seconds before automatically proceeding to the next slide. Therefore, students were expected to prepare a presentation that lasted six minutes and 40 seconds. In each group (i.e., freshmen, sophomore, junior), one volunteer student who was excluded from the study prepared a PK presentation to exemplify to his/her group how the presentation should look. These presentations were checked by the course instructor, who is also the researcher, to make sure that they would be in line with the PK format.

After the training sessions, participants were allowed to choose the topic they would like to prepare a creative PK presentation about. The topics were negotiated with the course instructor. The selected presentation topics covered a range of social and academic issues, such as food, animals, health, and overpopulation.

Three weeks before students started to prepare their PKs, the questionnaire aiming to identify their level of public speaking anxiety was given to the students as the pre-test. All the students performed their PKs on the scheduled days within a 7-week time frame. During their preparation time, they were encouraged to confer with the instructor when they needed help. On the day of the presentation, both the instructor and the students gave feedback to the presenter regarding the quality of the presentation in accordance with the principles of PK presentation style. Immediately after each presentation, the presenter was asked to fill out the questionnaire as the post-test by considering the possible effect of PK on their English public speaking anxiety. It took approximately seven minutes to complete the questionnaire.

Data Analysis

The data obtained by means of the pre- and post-tests were analyzed using a Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 23). To calculate whether there is a significant difference between the pre-test and post-test scores of the sub-dimensions in the questionnaire, the paired sample t-test was applied.

Findings

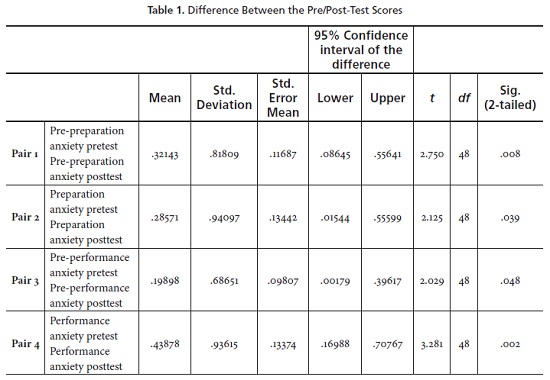

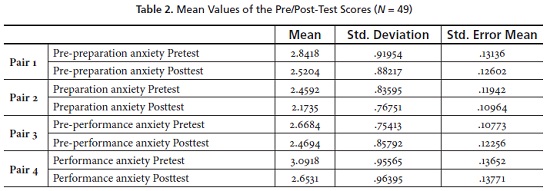

The paired samples statistics of the pre- and post-test scores of each factor (i.e., Items 1-4: pre-preparation anxiety; Items 5-8: preparation anxiety; Items 9-12: pre-performance anxiety; Items 13-16: performance anxiety) were analyzed, and the following findings illustrated in Table 1 and Table 2 were revealed in relation to the research question “What is the effect of Pecha Kucha presentation format on students’ English public speaking anxiety?”

As can be understood from Table 1, the p-values (Sig.) reached, as a result of the paired sample t-test, are less than 0.05. This means that there is a significant difference between pre-test and post-test scores in terms of all pairs for each factor. In other words, students responded differently to the same questionnaire administered as pre-test and post-test before and after their PK experience.

From the mean scores in Table 2, it can be realized that the mean values of the factors are significantly higher in the pre-test. Considering that the questionnaire administered as pre-test and post-test is related to the four sub-dimensions of public speaking anxiety level, it would be true to conclude that their English public speaking anxiety was reduced as a result of their involvement in preparing a pk presentation.

Discussion and Conclusion

In today’s world, public speaking skills are essential for both academia and for future employability (Hunter, Westwick, & Haleta, 2014). As in many other courses at the university level, effective presentation is an indispensable course component in English language courses (Simona, 2005). In the Turkish EFL context dominated by speaking anxiety and the unwillingness to speak English (Dil, 2009; Öztürk & Gürbüz, 2014), it is considered necessary to reduce EFL university students’ public speaking anxiety. With this necessity in mind, this study aims to reveal the impact of PK presentation format on EFL university students’ English public speaking anxiety by giving them a questionnaire as pre-test and post-test before and after they had experience in preparing and performing a PK presentation on a topic they selected themselves.

The questionnaire included items focusing on students’ anxiety levels at different stages of public speaking, such as pre-preparation, preparation, pre-performance, and performance. Participants’ responses to the pre-test and post-test were analyzed by means of SPSS, and a significant difference was found between their scores on these tests. It was uncovered that their public speaking anxiety level was significantly reduced as a result of their PK experience. This finding corroborates the assumptions and the findings of other researchers (Mabuan, 2016b; Swathipatnaik & Davidson, 2016; Tomsett & Shaw, 2014). According to these researchers, pk presentation format contributes to students’ confidence to speak English in public. It is also believed that PKs improve not only students’ presentation skills but also their confidence in public speaking by helping them overcome speech anxiety (Lucas & Rawlins, 2015).

The positive influence of PK on students’ public speaking anxiety can be justified by referring to the basic principles of this presentation format. As PK is a rigorous presentation style with time limitation, students have to practice and rehearse several times with a timer before the presentation. In other words, this presentation format forces the students to practice intensively as they cannot depend on text-heavy slides during presentations (Baker, 2014; Klentzin et al., 2010; Lucas & Rawlins, 2015). Because students are well-prepared for the real performance, it is likely that their public speaking anxiety will be reduced. As Simona (2005) argues, rehearsing a presentation raises speakers’ confidence and familiarizes them with the presentation content. Similarly, motivating students to practice speech by means of repetition and rehearsal is known to be a useful way to reduce public speaking anxiety, and thus to raise confidence in speaking (Liao, 2014). In a foreign language classroom, students tend to have the feeling that PK presentation is shorter and more manageable than the traditional presentation style and, consequently, they become more motivated to rehearse and practice for it (Lucas & Rawlins, 2015; Shiobara, 2015).

Competing with the time and not having words on slides might give rise to anxiety for some students but the anxiety PK causes can be considered as facilitative anxiety rather than debilitative anxiety (Scovel, 1978). It is true that PK presentation format might result in some tension but this tension can be associated with what Brown (2000) refers to as “just enough tension” to achieve a task. Therefore, facilitative anxiety is regarded as a good motivator that can keep the presenter alert and prevent the speaker from relaxing entirely. Similarly, in Bailey’s (1983) study, facilitative anxiety is thought to be one of the keys to success in language learning. Although the highly controlled nature of PK might seem to be a source of presentation anxiety, some students in the study carried out by Lucas and Rawlins (2015) stated that it is more convenient to prepare a PK than to plan a flexible five- to seven-minute presentation.

In line with the positive findings of this study and the benefits of the PK presentation format reviewed in the literature (Baker, 2014; Baskara, 2015; Lucas & Rawlins, 2015; Mabuan, 2016b; Nguyen, 2015; Ryan, 2012; Soto-Caban et al., 2011; Swathipatnaik & Davidson, 2016), the use of PK presentation style should be promoted especially in the university EFL contexts. The following recommendations can also be made for English language teachers, prospective English language teachers, EFL students, and researchers who are interested in the PK presentation style:

- English language teachers need to be aware of the fact that public speaking is an important skill that should be acquired by all English language learners; moreover, students’ speaking anxiety should be lowered as it hinders them from improving their speaking skills (Ciarrocca & Brown, 2015). Therefore, English language teachers can think of PK as an effective way of reducing students’ public speaking anxiety, but first they should familiarize themselves with the conventions of this presentation technique and incorporate it into their own teaching sessions. By this means, students’ awareness about the PK presentation format can be raised and they can become psychologically ready to use it for their presentations. As PK is quite different from the traditional presentation style, special training about how to prepare a PK presentation is deemed necessary for EFL students (Murugaiah, 2016; Zharkynbekova et al., 2017).

- The PK presentation style should also be integrated into pre-service EFL teacher training programs as it can contribute to prospective English language teachers’ instructive skills (Widyaningrum, 2016). Tüm and Kunt (2013) found in their study that Turkish-speaking EFL teacher candidates experience anxiety while speaking English, and they argue that the uncertainties of classroom discourse might be one of the reasons behind this. Besides, making PowerPoint presentations is regarded by candidate EFL teachers in Turkey as essential for their future careers (Özaslan & Maden, 2013), and it is known that the ability to use technology is one of the qualities of an effective language teacher (Kourieos & Evripidou, 2013). Having all these in mind, it is suggested that PK could be incorporated into pre-service EFL teacher training programs as an alternative way of presenting content.

- PK can be a part of EFL speaking classes, and it is favorable to give students the opportunity to select a topic they would like to talk about to allow creativity (Michaud, 2015). As Murugaiah (2016) states, students can also work in groups to prepare a PK project together because teamwork in the process of preparing a PK can lead to constructive discussion among group members, which leads to more effective presentations. From Murugaiah’s perspective, another positive aspect of group presentations is that weak students could be supported by more proficient English speakers while preparing a PK. The benefit of PK as a team building presentation format was also highlighted by some other researchers (Artyushina et al., 2010).

- Although there are reservations about the integration of PK into low proficiency level EFL classes (Murugaiah, 2016), this presentation format can be effectively integrated into EFL courses to help upper intermediate level students reduce their English public speaking anxiety or into English for academic purposes (EAP) courses (Robinson, 2015). On the other hand, Michaud (2015) acknowledges that encouraging low-level students to prepare PKs is hard but is also worth trying. He suggests that lower level students could start with presentations with 10 slides to be shown for 10 seconds each.

Even though the finding of this study is promising for the promotion of the PK presentation format as a means to lower students’ speech anxiety, the result of the study cannot be considered conclusive. The study has a limitation in that the finding is based on students’ self-perceptions of their English public speaking anxiety at the end of presenting only one PK. In further studies, students could present more than one PK and a similar questionnaire should be administered some time after the presentation performance to reveal the long-term effect of this presentation format on students’ public speaking anxiety. Also, by adding some open-ended questions to the questionnaire, further studies could uncover the inner feelings of the presenter before, while, and after preparing and presenting a PK. Finally, the effect of PK presentation format on EFL students’ fluency could be explored in further studies.

References

Artyushina, G., Sheypak, O., & Khovrin, A. (2010, April). Developing student presentation skills at the English language classes through Pecha Kucha. Paper presented at the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Amman, Jordan.

Ayres, J., & Hopf, T. (1993). Coping with speech anxiety. Norwood, US: Ablex Publishing.

Bailey, K. (1983). Competitiveness and anxiety in adult second language leaning: Looking at and through the diary studies. In H. W. Seliger & M. H. Long. (Eds.), Classroom-oriented research in second language acquisition (pp. 67-102). Rowley, US: Newbury House.

Baker, T. J. (2014). Pecha Kucha & English language teaching: Changing the classroom. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Baskara, R. (2015, May). Developing students’ autonomy in oral presentations through Pecha Kucha. Paper presented at the Teaching English as a Foreign Language Conference, University of Muhammadiyah Purwokerto, Indonesia.

Beatty, M. J., & Friedland, M. H. (1990). Public speaking state anxiety as a function of selected situational and predispositional variables. Communication Education, 39(2), 142-147. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634529009378796.

Beyer, A. M. (2011). Improving student presentations: Pecha Kucha and just plain PowerPoint. Teaching of Psychology, 38(2), 122-126. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628311401588.

Beyer, A. A., Gaze, C., & Lazicki, J. (2012). Comparing students’ evaluations and recall for student Pecha Kucha and PowerPoint presentations. Journal of Teaching and Learning with Technology, 1(2), 26-42.

Brown, H. D. (2000). Principles of language learning and teaching (4th ed.). New York, US: Longman.

Burnley, M., Cross, P., & Spanos, N. (1993). The effects of stress inoculation training and skills training on the treatment of speech anxiety. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 12, 355-366. https://doi.org/10.2190/N6TK-AR8Q-L4E9-0RJ0.

Cheng, Y.-S., Horwitz, E. K., & Schallert, D. L. (1999). Language anxiety: Differentiating writing and speaking components. Language Learning, 49(3), 417-446. https://doi.org/10.1111/0023-8333.00095.

Christianson, M., & Payne, S. (2011). Helping students develop skills for better presentations: Using the 20x20 format for presentation training. Language Research Bulletin, 26, 1-15.

Ciarrocca, B., & Brown, A. (2015, June 25). Fostering public speaking through Pecha Kucha in the high school English classroom. Paper presented at the Annual Research Forum, Winston-Salem, USA.

Foyle, H. C., & Childress, M. D. (2015). Pecha Kucha for better PowerPoint presentations. National Social Science Association. Retrieved from http://www.nssa.us/tech_journal/volume_1-1/vol1-1_article2.htm.

García-Laborda, J., (2013). Alternative assessment in English for tourism through web 2.0. In G. Bosch & T. Schlak (Eds.), Teaching foreign languages for tourism (pp. 89-106). New York, US: Peter Lang.

García-Laborda, J., & Litzler, M. F. (2015). Current approaches in teaching English for specific purposes. Revista Onomázein, 31, 38-51. https://doi.org/10.7764/onomazein.31.1.

García Laborda, J., & Litzler, M. F. (2017). English for business: Student responses to language learning through social networking tools. ESP Today, 5(1), 91-107. https://doi.org/10.18485/esptoday.2017.5.1.5.

Holliday, J. (2013). Pecha Kucha rubric. Retrieved from https://docs.google.com/document/d/10k5YlYOMtaXpisdUwu93eEPD03r9xnq28ACRswWfNYY/edit.

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 70(2), 125-132. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1986.tb05256.x.

Hunter, K. M., Westwick, J. N., & Haleta, L. L. (2014). Assessing success: The impacts of a fundamentals of speech course on decreasing public speaking anxiety. Communication Education, 63(2), 124-135. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2013.875213.

Klentzin, J. C., Paladino, E. B., Johnston, B. & Devine, C. (2010). Pecha Kucha: Using “lightning talk” in university instruction. Reference Services Review, 38(1), 158-167. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907321011020798.

Kourieos, S., & Evripidou, D. (2013). Students’ perceptions of effective EFL teachers in university settings in Cyprus. English Language Teaching, 6(11), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v6n11p1.

Liao, H.-A. (2014). Examining the role of collaborative learning in a public speaking course. College Teaching, 62(2), 47-54. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2013.855891.

Lucas, K., & Rawlins, J. D. (2015). PechaKucha presentations: Teaching storytelling, visual design, and conciseness. Communication Teacher, 29(2), 102-107. https://doi.org/10.1080/17404622.2014.1001419.

Mabuan, R. A. (2016a, April). Developing ELL’s public speaking skills. Paper presented at the Asianization of English and English Language Teaching Conference, Silliman University, Dumaguete, Negros Oriental.

Mabuan, R. A. (2016b, December). Pecha Kucha presentations: Building and boosting English language learners’ public speaking skills. Paper presented at the 11th International Symposium on Teaching English at Tertiary Level, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Kowloon, Hong Kong.

McCroskey, J. C. (1970). Measures of communication-bound anxiety. Speech Monographs, 37(4), 269-277. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637757009375677.

Michaud, M. (2015). Pecha Kucha in EFL: Creating creative presentations. Classroom Resources, 1, 9-24.

Murugaiah, P. (2016). Pecha Kucha style PowerPoint presentation: An innovative call approach to developing presentation skills of tertiary students. Teaching English with Technology, 16(1), 88-104.

Nguyen, H. (2015). Student perceptions of the use of PechaKucha presentations for EFL reading classes. Language Education in Asia, 6(2), 135-149. https://doi.org/10.5746/LEiA/15/V6/I2/A5/Nguyen.

Özaslan, E. N., & Maden, Z. (2013). The use of PowerPoint presentations in the department of foreign language education at Middle East Technical University. Middle Eastern and African Journal of Educational Research, 2, 38-45.

Öztürk, G., & Gürbüz, N. (2014). Speaking anxiety among Turkish EFL learners: The case at a state university. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 10(1), 1-17.

Plangkham, B., & Porkaew, K. (2012). Anxiety in English public speaking classes among Thai EFL undergraduate students. LEARN Journal: Language and Acquisition Research Network, 5, 110-119.

Reynolds, G. (2012). Presentation Zen: Simple ideas on presentation design and delivery. Berkeley, US: New Riders Publishing.

Robinson, R. (2015, July). Pecha Kucha: How to improve students’ presentation skills. Paper presented at the European Conference on Language Learning, Brighton, United Kingdom.

Ryan, J. (2012). PechaKucha presentations: What are they and how can we use them in the classrooms? Shizuoka University of Art and Culture Bulletin, 12, 23-27.

Scovel, T. (1978). The effect of affect on foreign language learning: A review of the anxiety research. Language Learning, 28(1), 129-142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1978.tb00309.x.

Shiobara, F. (2015, April-May). Pechakucha presentations in the classroom: Supporting language learners with public speaking. Paper presented at the Asian Conference on Language Learning, Kobe, Japan.

Simona, C. E. (2015). Developing presentation skills in the English language courses for the engineering students of the 21st century knowledge society: A methodological approach. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 203, 69-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.08.261.

Simpson, M. L., Parker, P. W., & Harrison, A. W. (1995). Differential performance on Taylor’s Manifest Anxiety Scale in black private college freshmen: A partial report. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 80, 699-702. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1995.80.2.699.

Snow, J. (2006, June). 20/20 Vision: The Tokyo-born Pecha Kucha phenomenon has the global creative community hooked. Metropolis, (637). Retrieved from http://archive.metropolis.co.jp/tokyo/637/feature.asp.

Soto-Caban, S., & Selvi, E., & Avila-Medina, F. (2011, June). Improving communication skills: Using PechaKucha style in engineering courses. Paper presented at 2011 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Vancouver, Canada.

Swathipatnaik, D., & Davidson, L. M. (2016). Pecha Kucha: An innovative task for engineering students. Research Journal of English Language and Literature, 4(4), 49-54.

Tok, H. (2009). EFL learners’ communication obstacles. Electronic Journal of Social Sciences, 8(29), 84-100.

Tomsett, P. M., & Shaw, M. R. (2014). Creative classroom experience using Pecha Kucha to encourage ESL use in undergraduate business courses: A pilot study. International Multilingual Journal of Contemporary Research, 2(2), 89-108.

Tüm, D. Ö., & Kunt, N. (2013). Speaking anxiety among EFL student teachers. Hacettepe University Journal of Education, 28(3), 385-399.

Widyaningrum, L. (2016). Pecha Kucha: A way to develop presentation. Vision, 5(1), 57-74. https://doi.org/10.21580/vjv5i1860.

Young, D. J. (1990). An investigation of students’ perspectives on anxiety and speaking. Foreign Language Annals, 23(6), 539-553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.1990.tb00424.x.

Zharkynbekova, S., Zhussupova, R., & Suleimenova, S. (2017, June). Exploring PechaKucha in EFL learners’ public speaking performances. Paper presented at the 3rd International Conference on Higher Education Advances, Universitat Politecnica de Valencia, Spain.

About the Author

Abdullah Coskun teaches in the Department of Translation and Interpretation at Abant Izzet Baysal University, Bolu, Turkey. He earned his BA and MA degrees in ELT from Abant Izzet Baysal University. He has a PhD in ELT from Middle East Technical University.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Sylvan Payne for his encouragement and advice, Benjawan Plengkham for the permission to use her questionnaire, Hung Nguyen for his useful comments on an earlier draft of this paper, and Zoe Marlowe for proofreading the paper.

References

Artyushina, G., Sheypak, O., & Khovrin, A. (2010, April). Developing student presentation skills at the English language classes through Pecha Kucha. Paper presented at the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Amman, Jordan.

Ayres, J., & Hopf, T. (1993). Coping with speech anxiety. Norwood, US: Ablex Publishing.

Bailey, K. (1983). Competitiveness and anxiety in adult second language leaning: Looking at and through the diary studies. In H. W. Seliger & M. H. Long. (Eds.), Classroom-oriented research in second language acquisition (pp. 67-102). Rowley, US: Newbury House.

Baker, T. J. (2014). Pecha Kucha & English language teaching: Changing the classroom. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Baskara, R. (2015, May). Developing students’ autonomy in oral presentations through Pecha Kucha. Paper presented at the Teaching English as a Foreign Language Conference, University of Muhammadiyah Purwokerto, Indonesia.

Beatty, M. J., & Friedland, M. H. (1990). Public speaking state anxiety as a function of selected situational and predispositional variables. Communication Education, 39(2), 142-147. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634529009378796.

Beyer, A. M. (2011). Improving student presentations: Pecha Kucha and just plain PowerPoint. Teaching of Psychology, 38(2), 122-126. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628311401588.

Beyer, A. A., Gaze, C., & Lazicki, J. (2012). Comparing students’ evaluations and recall for student Pecha Kucha and PowerPoint presentations. Journal of Teaching and Learning with Technology, 1(2), 26-42.

Brown, H. D. (2000). Principles of language learning and teaching (4th ed.). New York, US: Longman.

Burnley, M., Cross, P., & Spanos, N. (1993). The effects of stress inoculation training and skills training on the treatment of speech anxiety. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 12, 355-366. https://doi.org/10.2190/N6TK-AR8Q-L4E9-0RJ0.

Cheng, Y.-S., Horwitz, E. K., & Schallert, D. L. (1999). Language anxiety: Differentiating writing and speaking components. Language Learning, 49(3), 417-446. https://doi.org/10.1111/0023-8333.00095.

Christianson, M., & Payne, S. (2011). Helping students develop skills for better presentations: Using the 20x20 format for presentation training. Language Research Bulletin, 26, 1-15.

Ciarrocca, B., & Brown, A. (2015, June 25). Fostering public speaking through Pecha Kucha in the high school English classroom. Paper presented at the Annual Research Forum, Winston-Salem, USA.

Foyle, H. C., & Childress, M. D. (2015). Pecha Kucha for better PowerPoint presentations. National Social Science Association. Retrieved from http://www.nssa.us/tech_journal/volume_1-1/vol1-1_article2.htm.

García-Laborda, J., (2013). Alternative assessment in English for tourism through web 2.0. In G. Bosch & T. Schlak (Eds.), Teaching foreign languages for tourism (pp. 89-106). New York, US: Peter Lang.

García-Laborda, J., & Litzler, M. F. (2015). Current approaches in teaching English for specific purposes. Revista Onomázein, 31, 38-51. https://doi.org/10.7764/onomazein.31.1.

García Laborda, J., & Litzler, M. F. (2017). English for business: Student responses to language learning through social networking tools. ESP Today, 5(1), 91-107. https://doi.org/10.18485/esptoday.2017.5.1.5.

Holliday, J. (2013). Pecha Kucha rubric. Retrieved from https://docs.google.com/document/d/10k5YlYOMtaXpisdUwu93eEPD03r9xnq28ACRswWfNYY/edit.

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 70(2), 125-132. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1986.tb05256.x.

Hunter, K. M., Westwick, J. N., & Haleta, L. L. (2014). Assessing success: The impacts of a fundamentals of speech course on decreasing public speaking anxiety. Communication Education, 63(2), 124-135. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2013.875213.

Klentzin, J. C., Paladino, E. B., Johnston, B. & Devine, C. (2010). Pecha Kucha: Using “lightning talk” in university instruction. Reference Services Review, 38(1), 158-167. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907321011020798.

Kourieos, S., & Evripidou, D. (2013). Students’ perceptions of effective EFL teachers in university settings in Cyprus. English Language Teaching, 6(11), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v6n11p1.

Liao, H.-A. (2014). Examining the role of collaborative learning in a public speaking course. College Teaching, 62(2), 47-54. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2013.855891.

Lucas, K., & Rawlins, J. D. (2015). PechaKucha presentations: Teaching storytelling, visual design, and conciseness. Communication Teacher, 29(2), 102-107. https://doi.org/10.1080/17404622.2014.1001419.

Mabuan, R. A. (2016a, April). Developing ELL’s public speaking skills. Paper presented at the Asianization of English and English Language Teaching Conference, Silliman University, Dumaguete, Negros Oriental.

Mabuan, R. A. (2016b, December). Pecha Kucha presentations: Building and boosting English language learners’ public speaking skills. Paper presented at the 11th International Symposium on Teaching English at Tertiary Level, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Kowloon, Hong Kong.

McCroskey, J. C. (1970). Measures of communication-bound anxiety. Speech Monographs, 37(4), 269-277. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637757009375677.

Michaud, M. (2015). Pecha Kucha in EFL: Creating creative presentations. Classroom Resources, 1, 9-24.

Murugaiah, P. (2016). Pecha Kucha style PowerPoint presentation: An innovative call approach to developing presentation skills of tertiary students. Teaching English with Technology, 16(1), 88-104.

Nguyen, H. (2015). Student perceptions of the use of PechaKucha presentations for EFL reading classes. Language Education in Asia, 6(2), 135-149. https://doi.org/10.5746/LEiA/15/V6/I2/A5/Nguyen.

Özaslan, E. N., & Maden, Z. (2013). The use of PowerPoint presentations in the department of foreign language education at Middle East Technical University. Middle Eastern and African Journal of Educational Research, 2, 38-45.

Öztürk, G., & Gürbüz, N. (2014). Speaking anxiety among Turkish EFL learners: The case at a state university. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 10(1), 1-17.

Plangkham, B., & Porkaew, K. (2012). Anxiety in English public speaking classes among Thai EFL undergraduate students. LEARN Journal: Language and Acquisition Research Network, 5, 110-119.

Reynolds, G. (2012). Presentation Zen: Simple ideas on presentation design and delivery. Berkeley, US: New Riders Publishing.

Robinson, R. (2015, July). Pecha Kucha: How to improve students’ presentation skills. Paper presented at the European Conference on Language Learning, Brighton, United Kingdom.

Ryan, J. (2012). PechaKucha presentations: What are they and how can we use them in the classrooms? Shizuoka University of Art and Culture Bulletin, 12, 23-27.

Scovel, T. (1978). The effect of affect on foreign language learning: A review of the anxiety research. Language Learning, 28(1), 129-142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1978.tb00309.x.

Shiobara, F. (2015, April-May). Pechakucha presentations in the classroom: Supporting language learners with public speaking. Paper presented at the Asian Conference on Language Learning, Kobe, Japan.

Simona, C. E. (2015). Developing presentation skills in the English language courses for the engineering students of the 21st century knowledge society: A methodological approach. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 203, 69-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.08.261.

Simpson, M. L., Parker, P. W., & Harrison, A. W. (1995). Differential performance on Taylor’s Manifest Anxiety Scale in black private college freshmen: A partial report. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 80, 699-702. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1995.80.2.699.

Snow, J. (2006, June). 20/20 Vision: The Tokyo-born Pecha Kucha phenomenon has the global creative community hooked. Metropolis, (637). Retrieved from http://archive.metropolis.co.jp/tokyo/637/feature.asp.

Soto-Caban, S., & Selvi, E., & Avila-Medina, F. (2011, June). Improving communication skills: Using PechaKucha style in engineering courses. Paper presented at 2011 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Vancouver, Canada.

Swathipatnaik, D., & Davidson, L. M. (2016). Pecha Kucha: An innovative task for engineering students. Research Journal of English Language and Literature, 4(4), 49-54.

Tok, H. (2009). EFL learners’ communication obstacles. Electronic Journal of Social Sciences, 8(29), 84-100.

Tomsett, P. M., & Shaw, M. R. (2014). Creative classroom experience using Pecha Kucha to encourage ESL use in undergraduate business courses: A pilot study. International Multilingual Journal of Contemporary Research, 2(2), 89-108.

Tüm, D. Ö., & Kunt, N. (2013). Speaking anxiety among EFL student teachers. Hacettepe University Journal of Education, 28(3), 385-399.

Widyaningrum, L. (2016). Pecha Kucha: A way to develop presentation. Vision, 5(1), 57-74. https://doi.org/10.21580/vjv5i1860.

Young, D. J. (1990). An investigation of students’ perspectives on anxiety and speaking. Foreign Language Annals, 23(6), 539-553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.1990.tb00424.x.

Zharkynbekova, S., Zhussupova, R., & Suleimenova, S. (2017, June). Exploring PechaKucha in EFL learners’ public speaking performances. Paper presented at the 3rd International Conference on Higher Education Advances, Universitat Politecnica de Valencia, Spain.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Carolina Clerici, María Florencia Becerra, Danisa Siomara Bastida, Carolina Chirino, Valérie France Gänswein, Alcides Juan Diego Caballero. (2021). Desarrollo de habilidades de oralidad académica en estudiantes universitarios de la cátedra de Inglés Técnico a través de presentaciones PechaKucha 20x20. Oralidad-es, 7, p.1. https://doi.org/10.53534/oralidad-es.v7aX7.

2. Osman Solmaz. (2019). Developing EFL Learners’ Speaking and Oral Presentation Skills through Pecha Kucha Presentation Technique. Turkish Online Journal of Qualitative Inquiry, , p.452. https://doi.org/10.17569/tojqi.592046.

3. Nevin Doğan, Meyreme Aksoy. (2026). The effectiveness of PechaKucha as a reinforcement tool in teaching vital signs skills to nursing students: A randomized controlled trial. Nurse Education Today, 156, p.106886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2025.106886.

4. Setberth Jonas Haramba, Walter C. Millanzi, Saada A. Seif. (2024). Effects of pecha kucha presentation pedagogy on nursing students’ presentation skills: a quasi-experimental study in Tanzania. BMC Medical Education, 24(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05920-2.

5. Chunping Zheng, Lili Wang, Ching Sing Chai. (2023). Self-assessment first or peer-assessment first: effects of video-based formative practice on learners’ English public speaking anxiety and performance. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 36(4), p.806. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2021.1946562.

6. Boran Toker, M. Bahadır Kalıpçı. (2022). Happiness among tourism students: a study on the effect of demographic variables on happiness. Anatolia, 33(3), p.299. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2021.1914119.

7. Setberth Jonas Haramba, Walter C. Millanzi, Saada A. Seif. (2023). Enhancing nursing student presentation competences using Facilitatory Pecha kucha presentation pedagogy: a quasi-experimental study protocol in Tanzania. BMC Medical Education, 23(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04628-z.

8. Kelly A. Warmuth, Alexandria H. Caple. (2022). Differences in Instructor, Presenter, and Audience Ratings of PechaKucha and Traditional Student Presentations. Teaching of Psychology, 49(3), p.224. https://doi.org/10.1177/00986283211006389.

9. Soraya García-Sánchez. (2022). Transferring Language Learning and Teaching From Face-to-Face to Online Settings. Advances in Mobile and Distance Learning. , p.26. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-8717-1.ch002.

10. Figen Erol Ursavaş, Aslı Tok Özen, Gözde Özaras Öz. (2024). Evaluation of the effect of stoma care training using the pechakucha method on stoma care skills and anxiety in nursing students: A single-blind randomized controlled trial. Nurse Education in Practice, 80, p.104106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2024.104106.

11. James S. Ave, Devin Beasley, Amy Brogan. (2020). A Comparative Investigation of Student Learning through PechaKucha Presentations in Online Higher Education. Innovative Higher Education, 45(5), p.373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-020-09507-9.

12. Hao Wu. (2024). The more, the better? A multivariate longitudinal study on L2 motivation and anxiety in EFL oral presentations. Frontiers in Education, 9 https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1394922.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

Copyright (c) 2017 Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.