Unusual location of Burkitt lymphoma in HIV patients. A report of two cases

Linfoma de Burkitt de localización inusual en pacientes con VIH. Reporte de dos casos

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/revfacmed.v72n2.110643Palabras clave:

Burkitt Lymphoma, HIV infections, Breast neoplasms, Pancreatic neoplasms, Case Reports (en)Linfoma de Burkitt, VIH, Neoplasias de la mama, Neoplasias pancreáticas, Informes de casos (es)

Descargas

Introduction: Burkitt lymphoma (BL) is a rare and fast-growing type of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. An increased incidence of BL has been reported in patients with HIV.

Case presentation: Case 1: A 42-year-old man with HIV (stage A2) on antiretroviral therapy (ART) was admitted to the emergency department of a quaternary care hospital in Bogotá D. C. (Colombia) due to abdominal pain and jaundice, receiving a diagnosis of obstructive biliary syndrome. Imaging studies showed a mass in the pancreas, which was later identified as a BL through histopathological analysis. R-DA EPOCH protocol chemotherapy was started, but this regimen was later changed to Hyper-CVAD due to evidence of central nervous system involvement; ART was also adjusted due to drug interactions. Currently, the patient is awaiting initiation of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for the management of the BL. Case 2: A 28-year-old woman with HIV (stage C3) on ART (poor adherence) was initially diagnosed with breast cancer. Given the poor response to the initial chemotherapy protocol, a new histological study was performed, leading to a diagnosis of BL in the breast. The patient also presented with pulmonary cryptococcosis. Once treatment for pulmonary cryptococcosis was completed, a new chemotherapy regimen was started (R-CHOP protocol) and ART was adjusted to tenofovir/emtricitabine and raltegravir, achieving complete resolution of the BL after 6 cycles of chemotherapy.

Conclusion: In HIV patients with masses in atypical locations, a high index of suspicion for high-grade lymphoproliferative neoplasms such as BL should be considered. By reporting these cases, we expect to expand the knowledge of this type of unusual presentations of BL and, hence, improve the probabilities of a timely diagnosis in this population.

Introducción. El linfoma de Burkitt (LB) es un tipo de linfoma no Hodgkin poco frecuente y de rápido crecimiento. Se ha reportado una mayor incidencia de LB en pacientes con VIH.

Presentación de los casos. Caso 1: hombre de 42 años con VIH (estadio A2) en terapia antirretroviral (TARV) que ingresó al servicio de urgencias de un hospital oncológico de cuarto nivel de Bogotá D. C. (Colombia) por dolor abdominal e ictericia y fue diagnosticado con síndrome biliar obstructivo. En estudios de imagen se identificó masa en el páncreas que luego fue diagnosticada como LB mediante estudio histopatológico, por lo que se inició quimioterapia con protocolo R-DA EPOCH, el cual posteriormente fue cambiado a Hyper-CVAD debido a evidencia de compromiso del sistema nervioso central, ajustando también la TARV a disoproxil fumarato/emtricitabina/dolutegravir por la presencia de interacciones farmacológicas. Actualmente, el paciente está a la espera de iniciar terapia de trasplante autólogo de células progenitoras hematopoyéticas para consolidar el manejo del LB. Caso 2: mujer de 28 años con VIH (estadio C3) en TARV (mala adherencia) inicialmente diagnosticada con cáncer de mama. Ante la pobre respuesta al esquema inicial de quimioterapia, se realizó un nuevo análisis histológico y con base en los hallazgos se diagnosticó con LB en mama; la paciente también presentó criptococosis pulmonar. Una vez completó el tratamiento para la criptococosis pulmonar, se inició nuevo esquema de quimioterapia (R-CHOP) y se ajustó la TARV a Tenofovir/Emtricitabina y Raltegravir, logrando la resolución completa del LB luego de 6 ciclos de quimioterapia.

Conclusión. En pacientes con VIH y masas en localizaciones atípicas se debe tener un alto índice de sospecha de neoplasias linfoproliferativas de alto grado como el LB. Mediante los casos aquí reportados esperamos ampliar el conocimiento de este tipo de presentaciones inusuales del LB y, de esa forma, mejorar las probabilidades de un diagnóstico oportuno en esta población.

Case report

Unusual location of Burkitt lymphoma in HIV patients. A report of two cases

Linfoma de Burkitt de localización inusual en pacientes con VIH. Reporte de dos casos

Federico Solórzano-Torrejano1,2 Cristian Leonardo Cubides-Cruz2,3

Cristian Leonardo Cubides-Cruz2,3 Cynthia Ortiz-Roa1,4

Cynthia Ortiz-Roa1,4 Rafael Parra-Medina5

Rafael Parra-Medina5 Sonia Isabel Cuervo-Maldonado1,2,3

Sonia Isabel Cuervo-Maldonado1,2,3

1 Universidad Nacional de Colombia - Bogotá Campus - Faculty of Medicine - Department of Internal Medicine - Bogotá D.C. - Colombia.

2 Instituto Nacional de Cancerología, Universidad Nacional de Colombia - Bogotá Campus - Faculty of Medicine - Grupo de Investigación en Enfermedades Infecciosas y Alteraciones Hematológicas GREICAH - Bogotá D.C. - Colombia.

3 Instituto Nacional de Cancerología - Infectious Diseases Group - Bogotá D.C. - Colombia.

4 Universidad Nacional de Colombia - Bogotá Campus - Faculty of Medicine - Grupo de Investigación en Enfermedades Infecciosas - Bogotá D.C. - Colombia.

5 Instituto Nacional de Cancerología - Oncology Pathology Group - Bogotá D.C. - Colombia.

Open access

Received: 18/08/2023

Accepted: 10/04/2024

Corresponding author: Sonia Isabel Cuervo-Maldonado. Departamento de Medicina Interna, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Bogotá D.C. Colombia. E-mail: sicuervom@unal.edu.co.

Keywords: Burkitt Lymphoma; HIV infections; Breast neoplasms; Pancreatic neoplasms; Case Reports (MeSH).

Palabras clave: Linfoma de Burkitt; VIH; Neoplasias de la mama; Neoplasias pancreáticas; Informes de casos (DeCS).

How to cite: Solórzano-Torrejano F, Cubides-Cruz CL, Ortiz-Roa C, Parra-Medina R, Cuervo-Maldonado SI. Unusual location of Burkitt lymphoma in HIV patients. A report of two cases. Rev. Fac. Med. 2024;72(2):e110643. English. doi: https://doi.org/10.15446/revfacmed.v72n2.110643..

Cómo citar: Solórzano-Torrejano F, Cubides-Cruz CL, Ortiz-Roa C, Parra-Medina R, Cuervo-Maldonado SI. [Linfoma de Burkitt de localización inusual en pacientes con VIH. Reporte de dos casos]. Rev. Fac. Med. 2024;72(2):e110643. English. doi: https://doi.org/10.15446/revfacmed.v72n2.110643..

Copyright: Copyright: ©2024 Universidad Nacional de Colombia. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, as long as the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Introduction: Burkitt lymphoma (BL) is a rare and fast-growing type of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. An increased incidence of BL has been reported in patients with HIV.

Case presentation. Case 1: A 42-year-old man with HIV (stage A2) on antiretroviral therapy (ART) was admitted to the emergency department of a quaternary care hospital in Bogotá D. C. (Colombia) due to abdominal pain and jaundice, receiving a diagnosis of obstructive biliary syndrome. Imaging studies showed a mass in the pancreas, which was later identified as a BL through histopathological analysis. R-DA EPOCH protocol chemotherapy was started, but this regimen was later changed to Hyper-CVAD due to evidence of central nervous system involvement; ART was also adjusted due to drug interactions. Currently, the patient is awaiting initiation of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for the management of the BL. Case 2: A 28-year-old woman with HIV (stage C3) on ART (poor adherence) was initially diagnosed with breast cancer. Given the poor response to the initial chemotherapy protocol, a new histological study was performed, leading to a diagnosis of BL in the breast. The patient also presented with pulmonary cryptococcosis. Once treatment for pulmonary cryptococcosis was completed, a new chemotherapy regimen was started (R-CHOP protocol) and ART was adjusted to tenofovir/emtricitabine and raltegravir, achieving complete resolution of the BL after 6 cycles of chemotherapy.

Conclusion: In HIV patients with masses in atypical locations, a high index of suspicion for high-grade lymphoproliferative neoplasms such as BL should be considered. By reporting these cases, we expect to expand the knowledge of this type of unusual presentations of BL and, hence, improve the probabilities of a timely diagnosis in this population.

Resumen

Introducción. El linfoma de Burkitt (LB) es un tipo de linfoma no Hodgkin poco frecuente y de rápido crecimiento. Se ha reportado una mayor incidencia de LB en pacientes con VIH.

Presentación de los casos. Caso 1: hombre de 42 años con VIH (estadio A2) en terapia antirretroviral (TARV) que ingresó al servicio de urgencias de un hospital oncológico de cuarto nivel de Bogotá D. C. (Colombia) por dolor abdominal e ictericia y fue diagnosticado con síndrome biliar obstructivo. En estudios de imagen se identificó masa en el páncreas que luego fue diagnosticada como LB mediante estudio histopatológico, por lo que se inició quimioterapia con protocolo R-DA EPOCH, el cual posteriormente fue cambiado a Hyper-CVAD debido a evidencia de compromiso del sistema nervioso central, ajustando también la TARV a disoproxil fumarato/emtricitabina/dolutegravir por la presencia de interacciones farmacológicas. Actualmente, el paciente está a la espera de iniciar terapia de trasplante autólogo de células progenitoras hematopoyéticas para consolidar el manejo del LB. Caso 2: mujer de 28 años con VIH (estadio C3) en TARV (mala adherencia) inicialmente diagnosticada con cáncer de mama. Ante la pobre respuesta al esquema inicial de quimioterapia, se realizó un nuevo análisis histológico y con base en los hallazgos se diagnosticó con LB en mama; la paciente también presentó criptococosis pulmonar. Una vez completó el tratamiento para la criptococosis pulmonar, se inició nuevo esquema de quimioterapia (R-CHOP) y se ajustó la TARV a Tenofovir/Emtricitabina y Raltegravir, logrando la resolución completa del LB luego de 6 ciclos de quimioterapia.

Conclusión. En pacientes con VIH y masas en localizaciones atípicas se debe tener un alto índice de sospecha de neoplasias linfoproliferativas de alto grado como el LB. Mediante los casos aquí reportados esperamos ampliar el conocimiento de este tipo de presentaciones inusuales del LB y, de esa forma, mejorar las probabilidades de un diagnóstico oportuno en esta población.

Introduction

Burkitt lymphoma (BL) is a rare, fast-growing B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) that occurs in 1-2% of adult NHL cases worldwide.1 There are three main types of BL: endemic, sporadic, and immunodeficiency-related (associated with HIV infection),1-3 and all three have translocations that increase Myc gene expression on chromosome 8.2,3

In 2020, according to data from Globocan (Global Cancer Observatory), NHL was the eighth most common cancer in Colombia, with a prevalence of 23.86 cases per 100 000 inhabitants, and the tenth leading cause of cancer-related death.4 Furthermore, according to a study conducted on 136 patients with HIV and cancer treated at the Instituto Nacional de Cancerología (National Cancer Institute or INC by its Spanish acronym) between 2007 and 2014, NHL was the most frequent AIDS-defining cancer (46 cases) in the country.5

However, although there are no data on the prevalence or incidence of BL in HIV patients in Colombia, there are studies on the subject in other regions. For example, a study conducted in the United States with data from the HIV/AIDS Cancer Match Study reports that the incidence of BL in this population was 22 cases per 100 000 person-years between 1980 and 2005.6

Due to immunodeficiency, BL has a higher incidence in people with HIV than in the general population, accounting for up to 35% of cases of HIV-associated lymphoma. It usually occurs in patients with CD4>200/µL since germinal centers become less active in people with inadequate levels of this cell type, reducing the likelihood of Myc gene translocations.7 BL is predominantly extranodal in people with HIV, with the most frequently affected sites being the gastrointestinal tract, bone marrow, and central nervous system (CNS).1

BL symptoms are usually related to the presence of an abdominal mass (abdominal pain, intestinal obstruction, or gastrointestinal bleeding) or bone marrow infiltration (acute leukemia), with low CD4 count and CNS involvement being poor prognostic factors.8

The primary presentation of BL in the pancreas and breast in people with HIV is rare. No cases of this type of cancer in such sites in HIV patients have been reported in Colombia, and its prevalence worldwide is unknown due to its low incidence.9-11

On the other hand, primary pancreatic lymphoma accounts for less than 1% of extranodal lymphomas and 0.7% of pancreatic malignancies.12 In turn, primary breast lymphoma accounts for less than 3% of extranodal lymphomas, 1% of all NHL, and 0.5% of all malignant breast tumors.13

Regarding the treatment of BL in HIV-positive individuals, it is recommended to continue antiretroviral therapy (ART) during chemotherapy.14 One of the most commonly used chemotherapeutic regimens is CODOX-M-IVAC (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin and methotrexate alternating with ifosfamide, etoposide and cytarabine).2 Additionally, the DA-EPOCH-R and SC-EPOCH-RR regimes aim to reduce the toxicity of treatment; however, the cytotoxic drugs included in these regimens do not cross the blood-brain barrier, so they are not prescribed for patients with CNS involvement.2 These regimes improve the prognosis of the disease with a median survival of more than 70%.2

As for concomitant ART, it must be individualized. In Colombia, the recommended schedule for initiation of ART is tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine + dolutegravir.15 ART has changed the prognosis of lymphomas in these patients, so it should be initiated early, regardless of CD4+ lymphocyte count and whether or not chemotherapy is planned.16

The following are two cases of a rare location of BL in patients with HIV infection: pancreas (case 1) and left breast (case 2).

Case presentation

Case 1

A 42-year-old man diagnosed with stage A2 HIV infection on ART with recently administered tenofovir/emtricitabine/efavirenz, presented to the emergency department of the INC in October 2021 with the following clinical signs and symptoms, which had been manifesting for the last two months: pain in the right upper quadrant, nausea, vomiting, progressive abdominal distension, jaundice, choluria, diaphoresis, and involuntary weight loss. On physical examination, the patient was hydrated and tachycardic and presented jaundiced skin and mucous membranes, as well as pain on palpation in the right upper quadrant; no masses or signs of portal hypertension were identified. Admission laboratory tests yielded the following findings: mild leukocytosis (10 980/uL), neutrophilia (70.6%), moderate anemia (7.1g/dL), conjugated hyperbilirubinemia (TB: 12.24mg/dL - DB: 11.35mg/dL), hypoalbuminemia (2.8g/dL), preserved kidney function, and elevated ALT/AST transaminases (2 84U/L and 4 16U/L, respectively).

Based on these clinical and laboratory findings, the patient was diagnosed with obstructive biliary syndrome with etiology to be confirmed and was admitted to the hospital. Also, due to suspicion of cholangitis, antibiotic therapy (ampicillin/sulbactam 12g/day for 10 days) was started.

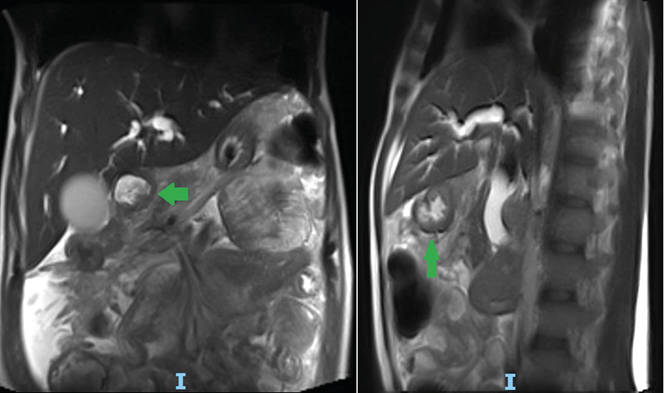

On the second day of admission, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the abdomen showed a mass in the head of the pancreas infiltrating the biliary tract, as well as loss of the cleavage plane with the second portion of the duodenum (Figure 1), which prompted a cholangiogram with bypass of the biliary tract on the fifth day of admission. The following day, follow-up lab tests showed a significant decrease in bilirubin levels (6.39mg/dL), which progressively decreased until normalizing on the ninth day of admission (1.02mg/dL).

Figure 1. MRI of the abdomen with gadolinium-based contrast medium. A) coronal plane; B) sagittal plane.

Note: The arrows show the mass in the head of the pancreas with involvement of the bile duct.

On the eighth day of admission, an endoscopy of the upper gastrointestinal tract showed a nodular, friable, and hard tumor-like lesion that occupied 50% of the second portion of the duodenum and involved 20% of the lumen, so a sample was collected for pathological study. The biopsy report of the lesion showed an atypical lymphoid infiltrate, while the immunohistochemical analysis showed that the lesion was compatible with tumor cells positive for CD20, PAX5, CD10, BCL6, c-MYC (95%), CD38 (weak), and P53 (5%), and negative for CD3, CD5, MUM1, BCL2, and Ki-67 (close to 100%) (Figure 2). Therefore, high-grade B-cell NHL was diagnosed with morphological and immunophenotypic features compatible with BL, and chemotherapy was initiated with R-DA EPOCH protocol (dose-adjusted etoposide, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide with vincristine and prednisone plus rituximab).

Figure 2. Biopsy of the mass in the duodenum. A) and B) starry sky pattern; C) positive for CD20; D) positive for BDL6; E) positive for c-MYC; F) Ki-67 close to 100%.

On the 29th day of admission, the patient presented left central facial paralysis, so an MRI of the brain was performed, which identified pachymeningitis and subdural hematomas, as well as an analysis of cerebrospinal fluid in which meningeal infiltration by the BL was confirmed, so intrathecal chemotherapy was added. The patient was discharged after 38 days and completed 5 cycles of chemotherapy in March 2022. However, a follow-up MRI of the brain in April 2022 confirmed BL relapse in the CNS, so chemotherapy was adjusted to Hyper-CVAD plus holocephalic radiotherapy. Also, due to the presence of drug-drug interactions, ART was adjusted to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine/dolutegravir.

A follow-up MRI of the brain in August 2022 confirmed the resolution of the infiltrative lesions. In July 2023, the patient completed the eighth cycle of the R-Hyper-CVAD protocol (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone, rituximab alternating with methotrexate and cytarabine) and in the last follow-up (September 2023) it was decided to consolidate the treatment of BL with autologous hematopoietic progenitor cell transplantation.

Case 2

A 28-year-old woman diagnosed with stage C3 HIV infection on ART with ritonavir/atazanavir + tenofovir/emtricitabine since 2008 but with poor adherence presented to the outpatient clinic of an oncology center in Ibagué (Colombia) in July 2017 due to a mass in the upper part of the left breast, which led to the performance of a computed axial tomography (CT) scan of the thorax showing the presence of a multilobulated mass in the left mammary gland that occupied practically the entire breast. A fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) was also performed, confirming the diagnosis of breast cancer, so chemotherapy (carboplatin+paclitaxel) was started. Six months after the initial consultation, the patient had received two cycles of chemotherapy, but showed no improvement, so the tumor biopsy was reviewed again and the diagnosis of BL was confirmed, so she was referred to the INC for treatment.

In January 2018, the patient went to the outpatient infectious disease service at the INC, where an HIV viral load of 164 617 copies/mL was documented (log10: 5.22), as well as a CD4+ cell count of 101 cells/mm3, thus, ART was adjusted to raltegravir + tenofovir/emtricitabine. On contrast-enhanced chest CT taken in February 2018, a solid, slightly hyperdense lesion involving the parenchyma of the upper quadrants of the left breast was observed, as well as a cavitary lung lesion in the right upper lobe and pleural nodule, probably caused by cryptococcosis (Figure 3). This infection was confirmed in the biopsy of the lung lesion, which reported the presence of abundant round or oval yeasts with thick capsule positive for PAS (periodic acid-Schiff) and Gomori-Grocott (methenamine silver) stains that was morphologically compatible with Cryptococcus spp.

Figure 3. Contrast-enhanced chest computed tomography.

Likewise, upon reviewing the results of the biopsy of the breast lesion performed at the first oncology center, a tumor lesion made up of large cells with the presence of cytopathic bodies and macrophages with tingible bodies inside them in a starry sky pattern was identified, thus confirming the diagnosis of BL in the left breast (Figure 4). Based on the findings of the extension studies, BL was classified as stage IIIb (retroperitoneal and cervical lymph node involvement, but no bone marrow involvement); in addition, the genetic study demonstrated the presence of translocation at t(8;14)(q24;q32), corresponding to the fusion of the IGH-MYC genes.

Figure 4. Breast tissue biopsy. A), B), and C) starry-sky pattern; D) positive for CD20; E) positive for BCL6; Ki-67 close to 100%.

Given these findings, the patient was admitted to the INC in February 2018 and received treatment for pulmonary cryptococcosis with amphotericin B deoxycholate, cumulative dose of 1g in the induction phase, then maintenance with fluconazole 800mg per day until completing 6 weeks of treatment, followed by secondary prophylaxis. One month later, the patient received the first cycle of chemotherapy with R-CHOP (rituximab, vincristine, doxorubicin, etoposide, cyclophosphamide). In August 2018, after 6 cycles of chemotherapy, complete resolution of BL was achieved. In November 2022, at the last follow-up with the hematology service at the INC, an HIV viral load of 111 copies was documented (log10: 2), as well as a CD4+ lymphocyte count of 451 cells/mm3. Finally, the patient reported regular attendance to an HIV management support program in her home city.

Discussion

Lymphomas are the most common type of cancer in HIV-infected individuals and comprise more than 50% of all AIDS-defining cancers, the most common being diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and BL.17 Moreover, it has been established that the risk for developing BL in patients with HIV ranges from 10% to 20%.18

Unlike other types of NHL in HIV patients, the development of ART has not reduced the incidence of BL in this population, as this cancer can occur in patients with normal CD4+ lymphocyte counts.19 In the two cases reported here, the patients were receiving ART, and although there was evidence of adequate immuno-virological control with treatment in case 1, the patient in case 2 had poor adherence, with a CD4+ cell count <200 cells/mm3 and an elevated viral load, making the latter an atypical case of presentation of this neoplasm.

It has been reported that individuals with HIV and lymphomas are more likely to have B symptoms and receive a diagnosis at advanced stages compared to HIV-negative patients.20 Both reported cases are highly relevant due to the unusual location of the BL (pancreas and breast) and the scarce medical literature on the subject.21-23 Furthermore, in both cases, the location of the lymphoma was challenging when it came to diagnosing the patients, given that other neoplasms occur at these locations more frequently than BL.24,25 However, the low response to cancer treatment and the presence of HIV infection were suggestive of BL, so atypical locations of this type of lymphoma should be suspected in similar cases.

In recent years, great advances have been made in the treatment of BL.2 High-intensity chemotherapy regimens have proven to be effective in achieving durable remission rates in HIV patients on ART. Available regimens include CODOX-M-IVAC (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, methotrexate alternating with ifosfamide, etoposide and cytarabine), R-Hyper-CVAD (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone, rituximab alternating with methotrexate and cytarabine), DA-EPOCH-R (dose-adjusted: etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin and rituximab), and SC-EPOCH-RR (etoposide, doxorubicin, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, prednisone, rituximab).2,26 As mentioned above, these last two regimens aim to reduce the toxicity of the treatment; however, the cytotoxic drugs included in these regimens do not cross the blood-brain barrier, which is why they should not be used in patients with CNS involvement.2

The cases presented here used the DA-EPOCH-R, R-Hyper-CVAD, and R-CHOP regimens; these regimens have been reported to be less toxic options for the treatment of BL.2 In case 1, facial paralysis made it necessary to rule out CNS involvement, so relapse was established and chemotherapy was adjusted, ensuring a complete response to treatment. In case 2, the patient presented with an infectious complication (pulmonary cryptococcosis) due to immunosuppression caused by poor adherence to ART and the resulting poor control of HIV infection.

Studies have demonstrated that concomitant ART with chemotherapy poses no additional risk and actually accelerates immune recovery.27 In general, antiretroviral drugs that should be avoided include those with myelosuppressive effects such as zidovudine and strong cytochrome P450 inhibitors and inducers, which have the most potential interactions with chemotherapy.2,28

In our case, both patients showed an adequate response to cancer treatment: the patient in case 1 relapsed, so the chemotherapy regimen was adjusted, and in case 2 the patient was in remission as evidenced in the last follow-up with the hematology service of the INC. In both cases, adjustments were made to the ART regimens based on potential interactions with chemotherapy, achieving an adequate and sustained immuno-virological response during the follow-up period, without the occurrence of adverse effects in terms of toxicity.

Conclusions

Patients with HIV infection are at increased risk of developing BL. This report describes two cases of extremely rare BL in patients with HIV infection (pancreas and breast). Considering the above, in individuals with HIV and masses in atypical locations, a high index of suspicion for high-grade lymphoproliferative neoplasms, such as BL, should be taken into account in order to achieve a timely diagnosis. Currently, chemotherapeutic treatment options include low toxicity regimens that, in combination with current ART options, allow concomitant treatment of BL and HIV, reducing the possibility of drug-drug interactions and improving the immunologic recovery of these patients.

Ethical considerations

The patients signed an informed consent granting permission for the publication of this case report and supporting images.

Conflicts of interest

None stated by the authors.

Funding

None stated by the authors.

Acknowledgments

None stated by the authors.

References

1.Roschewski M, Staudt LM, Wilson WH. Burkitt’s Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(12):1111-22. https://doi.org/gscczj.

2.Atallah-Yunes SA, Murphy DJ, Noy A. HIV-associated Burkitt lymphoma. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(8):594-600. https://doi.org/gknq2b.

3.Dunleavy K, Little RF, Wilson WH. Update on Burkitt Lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2016;30(6):1333-43. https://doi.org/f9jfcw.

4.International Agency for Research on Cancer: GLOBOCAN: Estimated cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence in Colombia in 2020. Cancer fact sheets. Lyon: Global Cancer Observatory; [cited 2024 Aug 13]. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/170-colombia-fact-sheets.pdf.

5.Álvarez-Guevara D, Cuervo-Maldonado S, Sánchez R, Gómez-Rincón J, Ramírez N. Prevalence of defining malignancies in adult patients with HIV/AIDS in the National Cancer Institute of Colombia. 2007-2014. Rev. Fac. Med. 2017;65(3):397-402. https://doi.org/ncn2.

6.Guech-Ongey M, Simard EP, Anderson WF, Engels EA, Bhatia K, Devesa SS, et al. AIDS-related Burkitt lymphoma in the United States: what do age and CD4 lymphocyte patterns tell us about etiology and/or biology? Blood. 2010;116(25):5600-4. https://doi.org/fn298n.

7.Meister A, Hentrich M, Wyen C, Hübel K. Malignant lymphoma in the HIV-positive patient. Eur J Haematol. 2018;101(1):119-26. https://doi.org/gpxhzw.

8.Linke-Serinsöz E, Fend F, Quintanilla-Martinez L. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) related lymphomas, pathology view point. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2017;34(4):352-63. https://doi.org/gf4hzw.

9.Konjeti VR, Hefferman GM, Paluri S, Ganjoo P. Primary Pancreatic Burkitt’s Lymphoma: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2018;2018:5952315. https://doi.org/gc9msj.

10.Vallejo-Diaz JF, Rodríguez R, Orduz R, Mantilla C, García JP, Vallejo-Diaz A. Linfoma de Burkitt primario de mama. Presentación de un caso. Rev. Colomb. Radiol. 2014;25(3):4036-9.

11.Rodríguez M, Grajales M, Londoño S, Ortiz N. Linfoma primario de mama: 23 años de experiencia en el Instituto Nacional de Cancerología. Revista Colombiana de Cancerología. 2004;8(3):39-46.

12.Luo G, Jin C, Fu D, Long J, Yang F, Ni Q. Primary pancreatic lymphoma. Tumori. 2009;95(2):156-9. https://doi.org/ncn3.

13.Cheah CY, Campbell BA, Seymour JF. Primary breast lymphoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40(8):900-8. https://doi.org/ncn4.

14.Noy A. Optimizing treatment of HIV-associated lymphoma. Blood. 2019;134(17):1385-94. https://doi.org/gqsg46.

15.Colombia. Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social (MinSalud). Guía de Práctica Clínica basada en la evidencia científica para la atención de la infección por VIH/SIDA en personas adultas, gestantes y adolescentes. Guía para profesionales de la salud. Bogotá D.C.: MinSalud; 2021 [cited 2024 Aug 12]. Available from: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/VS/PP/ET/gpc-vih-adultos-version-profesionales-salud.pdf.

16.Hübel K. The Changing Landscape of Lymphoma Associated with HIV Infection. Curr Oncol Rep. 2020;22(11):111. https://doi.org/ncn5.

17.Dolcetti R, Gloghini A, Caruso A, Carbone A. A lymphomagenic role for HIV beyond immune suppression? Blood. 2016;127(11):1403-9. https://doi.org/f8gwtj.

18.Noy A. Controversies in the treatment of Burkitt lymphoma in AIDS. Curr Opin Oncol. 2010;22(5):443-8. https://doi.org/b5qx5x.

19.Hernández-Ramírez RU, Qin L, Lin H, Leyden W, Neugebauer RS, Althoff KN, et al. Association of immunosuppression and HIV viraemia with non-Hodgkin lymphoma risk overall and by subtype in people living with HIV in Canada and the USA: a multicentre cohort study. Lancet HIV. 2019;6(4):240-9. https://doi.org/ncn7.

20.Han X, Jemal A, Hulland E, Simard EP, Nastoupil L, Ward E, et al. HIV Infection and Survival of Lymphoma Patients in the Era of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(3):303-11. https://doi.org/ncn8.

21.Kohashi S, Sakai A, Kodama Y. AIDS-Related Burkitt Lymphoma Presenting Multiple Nodules in the Pancreas. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(5):e920. https://doi.org/nc4t.

22.Graif M, Kessler A, Neumann Y, Martinowitz U, Itzchak Y. Pancreatic Burkitt lymphoma in AIDS: sonographic appearance. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149(6):1290-1. https://doi.org/nc4v.

23.Sandler AS, Kaplan L. AIDS lymphoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 1996;8(5):377-85. https://doi.org/ckfdvb.

24.Shetty AS, Menias CO. Rare Pancreatic Tumors. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2018;26(3):421-37. https://doi.org/ncn9.

25.Weigelt B, Geyer FC, Reis-Filho JS. Histological types of breast cancer: how special are they? Mol Oncol. 2010;4(3):192-208. https://doi.org/bk4v63.

26.Noy A. HIV Lymphoma and Burkitts Lymphoma. Cancer J. 2020;26(3):260-8. https://doi.org/ncpc.

27.Tan CRC, Barta SK, Lee J, Rudek MA, Sparano JA, Noy A. Combination antiretroviral therapy accelerates immune recovery in patients with HIV-related lymphoma treated with EPOCH: a comparison within one prospective trial AMC034. Leuk Lymphoma. 2018;59(8):1851-60. https://doi.org/ncpd.

28.Rubinstein PG, Aboulafia DM, Zloza A. Malignancies in HIV/AIDS: from epidemiology to therapeutic challenges. AIDS. 2014;28(4):453-65. https://doi.org/ncpf.

Referencias

1. Roschewski M, Staudt LM, Wilson WH. Burkitt’s Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(12):1111-22. https://doi.org/gscczj.

2. Atallah-Yunes SA, Murphy DJ, Noy A. HIV-associated Burkitt lymphoma. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(8):594-600. https://doi.org/gknq2b.

3. Dunleavy K, Little RF, Wilson WH. Update on Burkitt Lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2016;30(6):1333-43. https://doi.org/f9jfcw.

4. International Agency for Research on Cancer: GLOBOCAN: Estimated cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence in Colombia in 2020. Cancer fact sheets. Lyon: Global Cancer Observatory; [cited 2024 Aug 13]. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/170-colombia-fact-sheets.pdf.

5. Álvarez-Guevara D, Cuervo-Maldonado S, Sánchez R, Gómez-Rincón J, Ramírez N. Prevalence of defining malignancies in adult patients with HIV/AIDS in the National Cancer Institute of Colombia. 2007-2014. Rev. Fac. Med. 2017;65(3):397-402. https://doi.org/ncn2.

6. Guech-Ongey M, Simard EP, Anderson WF, Engels EA, Bhatia K, Devesa SS, et al. AIDS-related Burkitt lymphoma in the United States: what do age and CD4 lymphocyte patterns tell us about etiology and/or biology? Blood. 2010;116(25):5600-4. https://doi.org/fn298n.

7. Meister A, Hentrich M, Wyen C, Hübel K. Malignant lymphoma in the HIV-positive patient. Eur J Haematol. 2018;101(1):119-26. https://doi.org/gpxhzw.

8. Linke-Serinsöz E, Fend F, Quintanilla-Martinez L. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) related lymphomas, pathology view point. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2017;34(4):352-63. https://doi.org/gf4hzw.

9. Konjeti VR, Hefferman GM, Paluri S, Ganjoo P. Primary Pancreatic Burkitt’s Lymphoma: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2018;2018:5952315. https://doi.org/gc9msj.

10. Vallejo-Diaz JF, Rodríguez R, Orduz R, Mantilla C, García JP, Vallejo-Diaz A. Linfoma de Burkitt primario de mama. Presentación de un caso. Rev. Colomb. Radiol. 2014;25(3):4036-9.

11. Rodríguez M, Grajales M, Londoño S, Ortiz N. Linfoma primario de mama: 23 años de experiencia en el Instituto Nacional de Cancerología. Revista Colombiana de Cancerología. 2004;8(3):39-46.

12. Luo G, Jin C, Fu D, Long J, Yang F, Ni Q. Primary pancreatic lymphoma. Tumori. 2009;95(2):156-9. https://doi.org/ncn3.

13. Cheah CY, Campbell BA, Seymour JF. Primary breast lymphoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40(8):900-8. https://doi.org/ncn4.

14. Noy A. Optimizing treatment of HIV-associated lymphoma. Blood. 2019;134(17):1385-94. https://doi.org/gqsg46.

15. Colombia. Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social (MinSalud). Guía de Práctica Clínica basada en la evidencia científica para la atención de la infección por VIH/SIDA en personas adultas, gestantes y adolescentes. Guía para profesionales de la salud. Bogotá D.C.: MinSalud; 2021 [cited 2024 Aug 12]. Available from: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/VS/PP/ET/gpc-vih-adultos-version-profesionales-salud.pdf.

16. Hübel K. The Changing Landscape of Lymphoma Associated with HIV Infection. Curr Oncol Rep. 2020;22(11):111. https://doi.org/ncn5.

17. Dolcetti R, Gloghini A, Caruso A, Carbone A. A lymphomagenic role for HIV beyond immune suppression? Blood. 2016;127(11):1403-9. https://doi.org/f8gwtj.

18. Noy A. Controversies in the treatment of Burkitt lymphoma in AIDS. Curr Opin Oncol. 2010;22(5):443-8. https://doi.org/b5qx5x.

19. Hernández-Ramírez RU, Qin L, Lin H, Leyden W, Neugebauer RS, Althoff KN, et al. Association of immunosuppression and HIV viraemia with non-Hodgkin lymphoma risk overall and by subtype in people living with HIV in Canada and the USA: a multicentre cohort study. Lancet HIV. 2019;6(4):240-9. https://doi.org/ncn7.

20. Han X, Jemal A, Hulland E, Simard EP, Nastoupil L, Ward E, et al. HIV Infection and Survival of Lymphoma Patients in the Era of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(3):303-11. https://doi.org/ncn8.

21. Kohashi S, Sakai A, Kodama Y. AIDS-Related Burkitt Lymphoma Presenting Multiple Nodules in the Pancreas. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(5):e920. https://doi.org/nc4t.

22. Graif M, Kessler A, Neumann Y, Martinowitz U, Itzchak Y. Pancreatic Burkitt lymphoma in AIDS: sonographic appearance. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149(6):1290-1. https://doi.org/nc4v.

23. Sandler AS, Kaplan L. AIDS lymphoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 1996;8(5):377-85. https://doi.org/ckfdvb.

24. Shetty AS, Menias CO. Rare Pancreatic Tumors. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2018;26(3):421-37. https://doi.org/ncn9.

25. Weigelt B, Geyer FC, Reis-Filho JS. Histological types of breast cancer: how special are they? Mol Oncol. 2010;4(3):192-208. https://doi.org/bk4v63.

26. Noy A. HIV Lymphoma and Burkitts Lymphoma. Cancer J. 2020;26(3):260-8. https://doi.org/ncpc.

27. Tan CRC, Barta SK, Lee J, Rudek MA, Sparano JA, Noy A. Combination antiretroviral therapy accelerates immune recovery in patients with HIV-related lymphoma treated with EPOCH: a comparison within one prospective trial AMC034. Leuk Lymphoma. 2018;59(8):1851-60. https://doi.org/ncpd.

28. Rubinstein PG, Aboulafia DM, Zloza A. Malignancies in HIV/AIDS: from epidemiology to therapeutic challenges. AIDS. 2014;28(4):453-65. https://doi.org/ncpf.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Licencia

Derechos de autor 2024 Revista de la Facultad de Medicina

Esta obra está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento 3.0 Unported.

-