Publicado

Frecuencia de necesidades físicas no satisfechas identificadas en pacientes con enfermedades oncológicas o cardiovasculares crónicas en Popayán, Colombia

Frequency of unmet physical needs in patients with chronic oncological or cardiovascular diseases in Popayán, Colombia

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/revfacmed.v73.117113Palabras clave:

Cuidados Paliativos, Enfermedad Crónica, Neoplasias, Salud Holística, Evaluación de Síntomas, Carga Sintomática (es)Palliative Care, Chronic Illness, Neoplasms, Holistic Health, Symptom Assessment, Symptom Burden (en)

Descargas

Introducción. Los cuidados paliativos (CP) son esenciales en el manejo de pacientes con enfermedades oncológicas o cardiovasculares crónicas. A su vez, los CP requieren la identificación adecuada de las necesidades físicas y síntomas, lo cual se puede realizar a través de instrumentos estandarizados que permiten una valoración integral de la condición actual de los pacientes.

Objetivo. Determinar la frecuencia de necesidades físicas no satisfechas (NFNS) en pacientes con enfermedades oncológicas o cardiovasculares crónicas y atendidos en las salas de hospitalización de un hospital universitario de Popayán, Colombia.

Materiales y métodos. Estudio transversal descriptivo realizado en 441 pacientes con diagnóstico principal de cáncer o enfermedad cardiovascular hospitalizados en el Hospital San José de Popayán entre 2021 y 2022. La presencia de NFNS se determinó a partir de las respuestas en los 21 ítems del dominio Síntomas físicos de la versión validada en población colombiana del instrumento Sheffield Profile for Assessment and Referral for Care (SPARC-Sp).

Resultados. De los 441 pacientes, 340 (77.10%) tenían una enfermedad cardiovascular crónica como diagnóstico principal. Dolor fue la NFNS más frecuente (56.00%), seguido de sensación de cansancio (41.95 %) y sentir que los síntomas no están controlados (38.09 %). La mediana de NFNS fue 4 (RIQ: 2-7). La proporción de individuos en los que se determinó la presencia de una NFNS fue mayor en el grupo de pacientes con cáncer en 18 de los 21 ítems. De forma consecuente, los pacientes con cáncer tuvieron más NFNS (mediana de NFNS: 7 [RIQ: 4-9] vs. 3 [RIQ: 1-7]; p<0.001).

Conclusión. La mayoría de los pacientes presentaron NFNS, especialmente en el grupo oncológico, con una mediana significativamente más alta y una mayor proporción de individuos con una NFNS en 18 de los 21 ítems del SPARC-Sp.

Introduction: Palliative care (PC) is essential for the management of patients with chronic and oncologic diseases. In turn, PC requires proper identification of physical needs and symptoms, which can be achieved through standardized instruments that allow for a comprehensive assessment of the patients’ current condition.

Objective: To determine the frequency of unmet physical needs (UMPNs) in patients with chronic cardiovascular (CVD) or oncologic diseases treated in the inpatient wards of a university hospital in Popayán, Colombia.

Materials and methods: A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted in 441 patients with chronic cardiovascular disease or cancer as their primary diagnosis admitted to the Hospital San José in Popayán between 2021 and 2022. The presence of UMPN was determined based on the responses to the 21 items of the Physical Symptoms domain of the validated Colombian version of the Sheffield Profile for Assessment and Referral for Care (SPARC-Sp) instrument.

Results. Of the 441 patients, 340 (77.10%) had chronic cardiovascular disease as their primary diagnosis. Pain was the most frequent UMPN (56.00%), followed by fatigue (41.95 %), and the feeling of being unable to control symptoms (38.09 %). The median UMPN was 4 (IQR: 2-7). The proportion of individuals with UMPN was higher in the cancer patient group in 18 of the 21 items. Consequently, cancer patients had more UMPNs (median UMPN: 7 [IQR: 4-9] vs. 3 [IQR: 1-7]; p<0.001).

Conclusion: Most patients experienced UMPNs, especially in the oncology group, with a significantly higher median and a higher proportion of individuals with UMPNs in 18 of the 21 items of the SPARC-Sp.

Original research

Frequency of unmet physical needs in patients with chronic oncological or cardiovascular diseases in Popayán, Colombia

Frecuencia de necesidades físicas no satisfechas identificadas en pacientes con enfermedades oncológicas o cardiovasculares crónicas en Popayán, Colombia

Javier Stivens Orozco-Muñoz1 Laura Isabela Bolaños-Bocanegra1

Laura Isabela Bolaños-Bocanegra1 Camilo Cortés-Mora1

Camilo Cortés-Mora1 Karen Alejandra Rivera-Rivera1

Karen Alejandra Rivera-Rivera1 Cindy Vanesa Mendieta2,3,4

Cindy Vanesa Mendieta2,3,4 Sam Ahmedzai5

Sam Ahmedzai5 Esther de Vries2,6

Esther de Vries2,6 José Andrés Calvache1,7

José Andrés Calvache1,7

1 Universidad del Cauca - Faculty of Health Sciences - Department of Anesthesiology - Popayán - Colombia.

2 Pontificia Universidad Javeriana - Faculty of Medicine - Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics - Bogotá D.C. - Colombia.

3 Pontificia Universidad Javeriana - Faculty of Science - Department of Nutrition and Biochemistry - Bogotá D.C. - Colombia.

4 Pontificia Universidad Javeriana - Faculty of Nursing - Department of Collective Health Nursing - Bogotá D.C. - Colombia.

5 University of Sheffield - School of Medicine and Population Health - Sheffield - England.

6 Queen’s University Belfast - School of Nursing and Midwifery - Belfast - Northern Ireland.

7 Erasmus University Rotterdam - Erasmus MC - Anesthesiology Department - Rotterdam - Netherlands.

Open access

Received: 23/09/2024

Accepted: 24/07/2025

Corresponding author: José Andrés Calvache. Departamento de Anestesiología, Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad del Cauca. Popayán. Colombia. E-mail: jacalvache@unicauca.edu.co.

Keywords: Palliative Care; Chronic Illness; Neoplasms; Holistic Health; Symptom Assessment; Symptom Burden (MeSH).

Palabras clave: Cuidados Paliativos; Enfermedad Crónica; Neoplasias; Salud holística; Evaluación de síntomas; Carga sintomática (DeCS).

How to cite: Orozco-Muñoz JS, Bolaños-Bocanegra LI, Cortés-Mora C, Rivera-Rivera KA, Mendieta CV, Ahmedzai S, et al. Frequency of unmet physical needs in patients with chronic oncological or cardiovascular diseases in Popayán, Colombia. Rev. Fac. Med. 2025;73:e117113. English. doi: https://doi.org/10.15446/revfacmed.v73.117113.

Cómo citar: Orozco-Muñoz JS, Bolaños-Bocanegra LI, Cortés-Mora C, Rivera-Rivera KA, Mendieta CV, Ahmedzai S, et al. [Frecuencia de necesidades físicas no satisfechas identificadas en pacientes con enfermedades oncológicas o cardiovasculares crónicas en Popayán, Colombia]. Rev. Fac. Med. 2025;73:e117113. English. doi: https://doi.org/10.15446/revfacmed.v73.117113.

Copyright: ©2025 The Author(s). This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, as long as the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Introduction: Palliative care (PC) is essential for the management of patients with chronic and oncologic diseases. In turn, PC requires proper identification of physical needs and symptoms, which can be achieved through standardized instruments that allow for a comprehensive assessment of the patients’ current condition.

Objective: To determine the frequency of unmet physical needs (UMPNs) in patients with chronic cardiovascular (CVD) or oncologic diseases treated in the inpatient wards of a university hospital in Popayán, Colombia.

Materials and methods: A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted in 441 patients with chronic cardiovascular disease or cancer as their primary diagnosis admitted to the Hospital San José in Popayán between 2021 and 2022. The presence of UMPN was determined based on the responses to the 21 items of the Physical Symptoms domain of the validated Colombian version of the Sheffield Profile for Assessment and Referral for Care (SPARC-Sp) instrument.

Results. Of the 441 patients, 340 (77.10%) had chronic cardiovascular disease as their primary diagnosis. Pain was the most frequent UMPN (56.00%), followed by fatigue (41.95 %), and the feeling of being unable to control symptoms (38.09 %). The median UMPN was 4 (IQR: 2-7). The proportion of individuals with UMPN was higher in the cancer patient group in 18 of the 21 items. Consequently, cancer patients had more UMPNs (median UMPN: 7 [IQR: 4-9] vs. 3 [IQR: 1-7]; p<0.001).

Conclusion: Most patients experienced UMPNs, especially in the oncology group, with a significantly higher median and a higher proportion of individuals with UMPNs in 18 of the 21 items of the SPARC-Sp.

Resumen

Introducción. Los cuidados paliativos (CP) son esenciales en el manejo de pacientes con enfermedades oncológicas o cardiovasculares crónicas. A su vez, los CP requieren la identificación adecuada de las necesidades físicas y síntomas, lo cual se puede realizar a través de instrumentos estandarizados que permiten una valoración integral de la condición actual de los pacientes.

Objetivo. Determinar la frecuencia de necesidades físicas no satisfechas (NFNS) en pacientes con enfermedades oncológicas o cardiovasculares crónicas y atendidos en las salas de hospitalización de un hospital universitario de Popayán, Colombia.

Materiales y métodos. Estudio transversal descriptivo realizado en 441 pacientes con diagnóstico principal de cáncer o enfermedad cardiovascular hospitalizados en el Hospital San José de Popayán entre 2021 y 2022. La presencia de NFNS se determinó a partir de las respuestas en los 21 ítems del dominio Síntomas físicos de la versión validada en población colombiana del instrumento Sheffield Profile for Assessment and Referral for Care (SPARC-Sp).

Resultados. De los 441 pacientes, 340 (77.10%) tenían una enfermedad cardiovascular crónica como diagnóstico principal. Dolor fue la NFNS más frecuente (56.00%), seguido de sensación de cansancio (41.95 %) y sentir que los síntomas no están controlados (38.09 %). La mediana de NFNS fue 4 (RIQ: 2-7). La proporción de individuos en los que se determinó la presencia de una NFNS fue mayor en el grupo de pacientes con cáncer en 18 de los 21 ítems. De forma consecuente, los pacientes con cáncer tuvieron más NFNS (mediana de NFNS: 7 [RIQ: 4-9] vs. 3 [RIQ: 1-7]; p<0.001).

Conclusión. La mayoría de los pacientes presentaron NFNS, especialmente en el grupo oncológico, con una mediana significativamente más alta y una mayor proporción de individuos con una NFNS en 18 de los 21 ítems del SPARC-Sp.

Introduction

Palliative care (PC) refers to the active and comprehensive care of individuals who, regardless of age, are severely affected by chronic, progressive, or end-of-life illnesses.1-3 Its aim is to improve the quality of life of patients, their families, and caregivers by preventing and alleviating suffering through early identification, comprehensive assessment, and treatment of physical, emotional, social, and spiritual symptoms.1,2 This definition acknowledges that PC should be provided based on the patient’s needs rather than on the prognosis or stage of the disease, which means that PC is applicable in all hospital settings and levels of care, covering both general and specialized care.1,2,4

Timely access to PC is an essential component of health care, as well as a key factor in universal health coverage.1-5 However, there are still gaps in health care provision in most parts of the world due to various factors,1 such as a lack of awareness of its availability, misinformation about the appropriate use of certain medications like opioids, and the focus that existing health outcome measures (which are major drivers of health policy and investment) have on extending life and productivity, downplaying health interventions aimed at relieving pain or avoiding negative impacts on people’s dignity at the end of life.2,3

Patients with chronic diseases, mainly cancer, cerebrovascular diseases, kidney problems, and Alzheimer’s, often require PC due to the progressive deterioration of functional capacity resulting from these conditions.6-8 Thus, although PC was initially intended to alleviate suffering at the end of life, nowadays it is increasingly being used in the early stages of illness, with a focus on the needs of the patient and their family, rather than solely on numerical and objective tools. The aim is to take into account clinical factors, as well as psychological, health, and spiritual needs.7 The systematic and comprehensive assessment of symptoms and individual needs in each patient is key to establishing care and treatment goals and to promoting shared decision-making in both the short and long term.1

In Colombia, Law 1733 of 2014 regulates health care provided to individuals with terminal, chronic, degenerative, and irreversible diseases.9 Nevertheless, there is no general consensus on the best way to assess and evaluate the holistic needs of patients with advanced chronic diseases, nor is there solid evidence on their use in the hospital setting. In view of the above, the Ministry of Health and Social Protection, through the Clinical Practice Guideline for Palliative Care, established that the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS-r) and the Rotterdam Symptom Checklist can be used to assess symptoms in the context of studies evaluating the impact of palliative care.10

Similarly, although progress has been made in the implementation of PC programs in the country, according to the Colombian Palliative Care Observatory,11 there is no information on the needs perceived by these patients, which makes it difficult to develop effective detection and intervention strategies. This gap is particularly evident in the systematic assessment of these needs using structured instruments in hospitalized patients with chronic diseases, especially cardiovascular diseases, despite the fact that they, together with cancer, are important contributors to the burden of disease, disability, and mortality in the region.12,13

In clinical practice, there are several situations that contribute to the underreporting of intensity and occurrence of symptoms and patient needs, which differs from patients’ self-perception, especially cancer patients.14 PC requires proper identification of physical needs and symptoms, which can be achieved using standardized instruments that permit conducting a comprehensive assessment of the patients’ current condition, such as patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and patient-reported experience measures (PREMs).15-17

PROMs and PREMs are questionnaires used to collect information about patients’ perceptions of their health. Their implementation in clinical practice allows modifying treatment goals and supporting patients and their families in accordance with their individual values and preferences.16,17 In this regard, the Sheffield Profile for Assessment and Referral for Care (SPARC-Sp) questionnaire, validated for use in the Colombian population,18,19 is a PROM that comprehensively assesses the unmet holistic needs of patients on PC across the country in multiple domains.20

In view of the above, the objective of this study was to determine the frequency of unmet physical needs (UMPNs) in patients with chronic cardiovascular (CVD) or oncologic diseases treated in the inpatient wards of a university hospital in Popayán, Colombia. It should be noted that this study specifically aimed to identify the presence of UMPNs in the 21 items of the “Physical Symptoms” domain of the SPARC-Sp, which includes symptoms such as pain, fatigue, dyspnea, and persistent discomfort, in order to focus the analysis on the most common and objectifiable manifestations of these patients while receiving hospital care.

These results are intended to further elaborate on the early and comprehensive identification of these patients’ needs to facilitate the implementation of PC-based interventions with a holistic approach.

Materials and methods

Study type

Descriptive cross-sectional study.

Study population and sample

The study population included patients with chronic oncologic or cardiovascular diseases as their primary diagnosis treated in the inpatient wards (medical or surgical) of the Hospital Universitario San José (tertiary care center) in Popayán between June 2021 and July 2022. To determine whether a patient had a chronic cardiovascular disease, we used the definitions provided by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (conditions lasting ≥1 year and requiring ongoing medical care and/or limiting activities of daily living).21,22

It is worth pointing out that although the study population stems from the 507 patients who participated in the validation of the Spanish version of the SPARC instrument in the Colombian context,18,19 it does not include all of them (patients with a primary diagnosis of chronic disease, including cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, pulmonary, metabolic, and oncological diseases, among others). Since the present study only considered patients with oncologic diseases (at any stage) or chronic cardiovascular diseases as their primary diagnosis, data from 441 patients who met these eligibility criteria (n=340 and n=101, respectively) were analyzed.

It should also be noted that the study from which the data on these 441 patients was obtained did not include individuals with symptomatic brain metastases, uncontrolled psychological conditions, cognitive impairment, or those who were unable to communicate effectively with the researchers.

Procedures, data collection, and variables

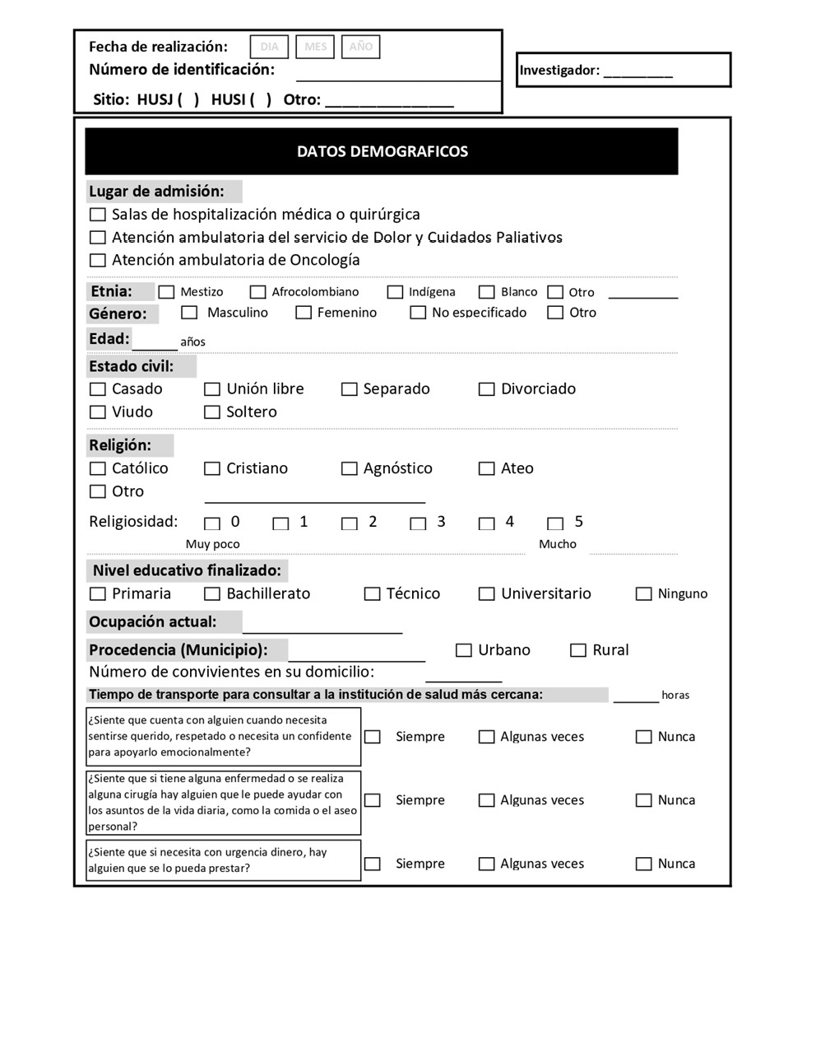

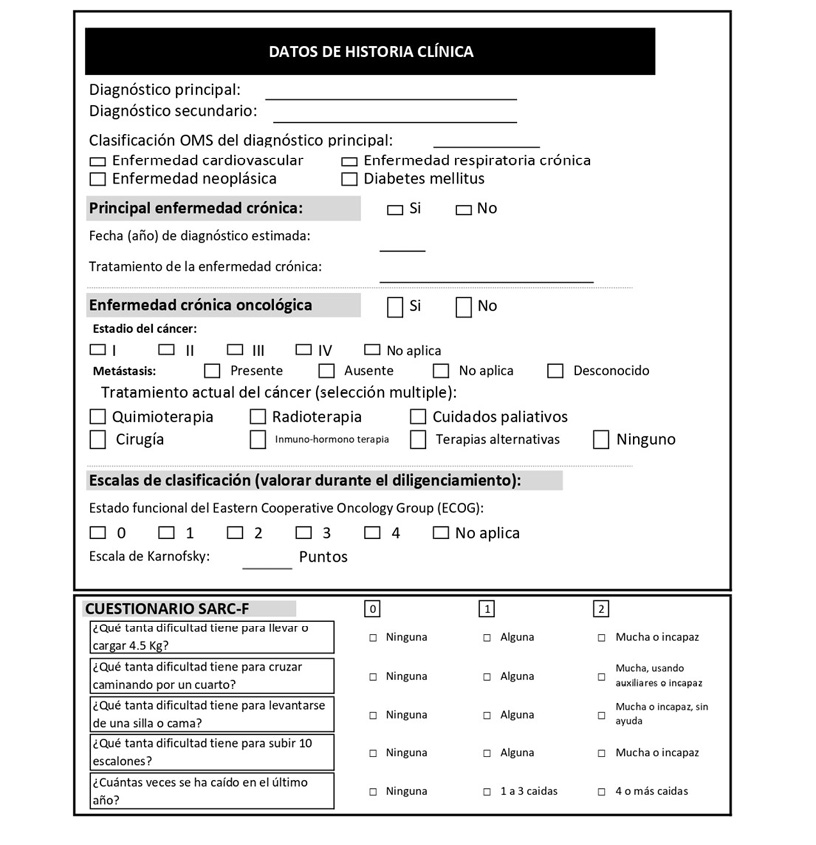

A data collection form (Annex 1) was used to gather the information obtained from the review of the medical records and the information directly provided by the patients during the administration of the SPARC -Sp. Data included biological sex, age, ethnicity (self-reported), place of residence (urban or rural area), educational level, primary diagnosis (chronic cardiovascular disease or cancer), years since diagnosis, presence of comorbidities, and functional status according to the Karnofsky Performance Scale.

The translated and validated version of the SPARC-Sp18,19 instrument for the Colombian population was administered individually and on paper during their hospital stay. Even though the SPARC-Sp instrument was designed to be completed by the patients themselves (self-report), if there were any difficulties reading or understanding one or more items, patients could ask for help from the person administering the instrument (duly trained research assistants).

Instruments

The Colombian Spanish version of the Sheffield Profile for Assessment and Referral for Care (SPARC-Sp) was used. This instrument was validated at the same health care center where the study was conducted,18,19 showing excellent overall internal reliability (α=0.91) and domain coefficients between 0.73 and 0.89.18 These metrics support their suitability for the multidimensional assessment of palliative needs among inpatients with chronic diseases in the Colombian context.

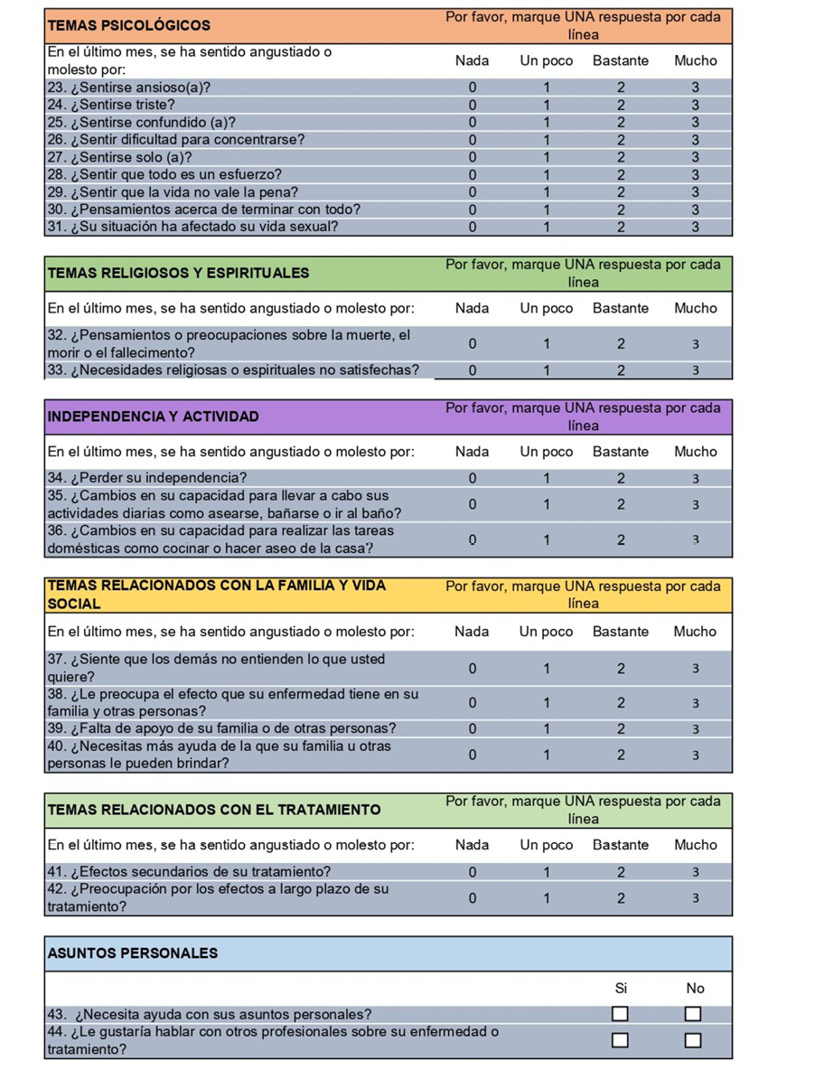

The SPARC-SP has 45 items grouped into 8 domains: Communication and information issues (1 item), Physical symptoms (21 items on the presence of pain, nausea/vomiting, fatigue, dyspnea, among others), Psychological issues (9 items), Religious and spiritual issues (2 items), Independence and activity issues (3 questions), Family and social issues (4 questions), Treatment issues (2 questions), and Personal issues (3 questions).

Of the 45 items, 4 are dichotomous questions (yes/no; included in the domains “Communication and information issues” and “Personal issues”) and the remaining 41 are evaluated using a 3-point Likert scale (0: not at all, 1: a little bit, 2: quite a bit, and 3: very much) based on the patient’s perception.18,19 The presence of a UMPN is established based on the patient’s response to the 21 items of the “Physical Symptoms” domain as follows: none or a few: no physical need; considerable or many; presence of a need. Thus, a patient may score in the range from 0 to 21 UMPNs.

The Karnofsky Performance Scale assesses the functional status, ability to perform daily activities, and independence of a chronic patient.23-26 While originally designed to measure functional status and short-term survival in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy,24,27 it is now widely used in patients with chronic diseases or other terminal illnesses.23-26,28 This scale has 11 items that vary depending on the patient’s functional status from 100 (normal functioning) to 0 (dead); in other words, the lower the score, the worse the individuals’ functional status.23-28

Statistical analysis

Data are described using absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables, and means and standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables, depending on the normality of the data (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and visual inspection of distributions using frequency histograms and Q-Q plots).29

Of note, the distribution of participants’ response options (not at all, a little bit, quite a bit, very much) for the 21 items in the Physical Symptoms domain is presented using a barplot created with the Likert barplot 2.0 package of the R Version 4.4.2 software,30 and the estimate of the frequency of patients who were found to have UMPNs for each item (quite a lot or very much) also included the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). Furthermore, a lollipop plot was used to depict the estimated proportion of patients with UMPNs for each of the 21 items in the two groups defined based on diagnosis (oncologic diseases vs. cardiovascular diseases).

Concerning inferential analysis, bivariate analyses (chi-square test and Wilcoxon rank sum test) were performed to evaluate differences between groups (patients with cancer diagnoses vs. patients with cardiovascular disease diagnoses) regarding the presence of comorbidities, the number of UMPNs, and the Karnofsky Performance Scale score. All analyses were performed using the statistical software R (version 4.4.2),30 and a statistical significance level of p<0.05 was considered.

Ethical considerations

The study adhered to the ethical principles for biomedical research involving human subjects established in the Declaration of Helsinki31 and the scientific, technical, and administrative standards for health research set forth in Resolution 8430 of 1993 issued by the Colombian Ministry of Health;32 also, according to that resolution, this study is classified as a minimal risk research. Likewise, the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario San José de Popayán as per minutes FO-ARH-01 dated May 21, 2021. All patients included confirmed their voluntary and informed participation by signing informed consent forms. Their personal details were anonymized.

Results

The mean age of patients was 68 years (SD=14.06), 58.50% were women, 77.56% self-identified as mixed-race, and 61.90% came from urban areas. The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients (n=441).

|

Variable |

n (%) |

|

|

Age (mean±SD) |

68±14.06 |

|

|

Sex |

Female |

258 (58.50) |

|

Male |

183 (41.50) |

|

|

Race |

Mixed-race |

342 (77.56) |

|

White |

48 (10.88) |

|

|

Indigenous |

26 (5.89) |

|

|

Afro-Colombian |

25 (5.67) |

|

|

Area of origin |

Urban areas or urban centers |

273 (61.90) |

|

Rural areas |

168 (38.10) |

|

|

Educational level |

Elementary school |

194 (43.99) |

|

High school |

141 (31.98) |

|

|

Technical school |

18 (4.08) |

|

|

University |

21 (4.76) |

|

|

None |

67 (15.19) |

|

|

Primary diagnosis |

Chronic cardiovascular disease |

340 (77.10) |

|

Chronic cancer |

101 (22.90) |

|

|

Years since primary diagnosis (median (IQR)) |

10.78 (3.00-14.00) |

|

With respect to the presence of comorbidities, 67.35% (n=297) had at least one, and 25.93% (n=77) of them had ≥2. The proportion of patients with at least one comorbidity was higher in the cardiovascular disease group than in the cancer group, with this difference being statistically significant (71.18% vs. 54.46%; p=0.002). The median Karnofsky Performance Scale score was 80 (IQR: 60-90), with no significant differences between groups (80 [IQR: 60-90] vs. 80 [IQR: 70-90]; p=0.8).

Frequency of unmet physical needs

Pain was the item with the highest proportion of patients in whom a UMPN was identified (n=247, 56.00%; 95% CI: 51-60), followed by fatigue (n=185, 41.95%; 95% CI: 37-46), and sense of having uncontrolled symptoms (n=168, 38.09%; 95%CI: 33-42). Figure 1 shows the frequency of the four response options for each of the 21 items in the Physical Symptoms domain (the information is presented in ascending order based on the proportion of patients who responded “quite a lot” or “very much,” i.e., who presented UMPNs).

Figure 1. Distribution of patients by the 4 response options in each of the 21 items in the Physical Symptoms domain of the SPARC-Sp.

The median UMPN score was 4 (IQR: 2-7), and the proportion of individuals for whom a UMPN was found (responses “quite a lot” or “very much”) was higher in the cancer group for all items of the Physical Symptoms domain, except for urinary incontinence, shortness of breath, and memory loss (Figure 2). For example, in the pain category, 28.70% of cancer patients had a UMPN, while in the cardiovascular disease group, this number was 17.92% (Figure 2). Consequently, cancer patients had greater physical needs than those with cardiovascular disease, with a significant difference (median physical needs: 7 [IQR: 4-9] vs. 3 [IQR 1-7]; p<0.001).

Figure 2. Proportion of patients for whom an unmet physical need was identified in each of the 21 items of the Physical Symptoms domain (patients with cancer vs. patients with cardiovascular disease).

Note: The vertical axis of the lollipop plot includes the 21 items or symptoms assessed with the instrument, while the horizontal axis represents the proportion of patients in each group in whom unmet physical needs were identified based on their responses (range 0-30%).

Discussion

The early incorporation of PC in the management of chronic diseases, both oncologic and non-oncologic, is a paradigm shift in the field of health care. This approach transforms the traditional model, which limited the use of PC to the terminal stages of the disease towards a broader and more proactive perspective, albeit it requires careful assessment of patients’ needs.6,33-36

In our study, at least half of the sample (patients hospitalized with chronic oncological or cardiovascular diseases) had a UMPN, with the most common symptoms being pain, fatigue, and feeling that symptoms were not under control. Furthermore, we found that, compared to patients with cardiovascular disease, patients with cancer as their primary diagnosis have more UMPNs. This difference could be explained by the greater symptom burden that cancer patients tend to experience, associated with the accelerated progression of certain types of cancer, as well as the adverse effects of treatments such as chemotherapy.37-39

As mentioned above, pain was the most frequent UMPN (56.00%), with the proportion of patients with a UMPN in this item being higher in the cancer group than in the cardiovascular disease group (28.70% vs. 17.92%). In this regard, it has been reported that pain is a common symptom in cancer patients, and that up to 40% suffer from chronic pain due to inadequate analgesic therapy.37,38,40

Pain in cancer patients not only impacts their physical function but also contributes to a poor quality of life and leads to psychological distress.41 This suggests that, despite existing guidelines for pain management in this population, there is still a significant gap in the implementation of effective strategies, reinforcing the need for early and personalized interventions. In this regard, the literature emphasizes that early integration of PC can significantly contribute to reducing pain and improving patient satisfaction and adherence to cancer treatments.42,43

On the other hand, pain associated with cardiovascular diseases involves multiple mechanisms, including inflammatory, nociceptive, and neuropathic processes.44 According to the literature, the prevalence of pain in patients with chronic heart failure (CHF) varies between 23.1% and 85% and increases as the patient’s functional status worsens.45

Fatigue was the second most common UMPN. This is consistent with the literature, which has established that chronic fatigue, defined as an overwhelming sense of tiredness that arises without provocation and cannot be relieved by rest,46 is a common symptom of many chronic diseases.46,47 Fatigue is a common symptom in cancer patients,37,39 with a prevalence ranging from 32% to 90% depending on the stage of the disease in patients with advanced cancer.42 This condition is not monitored in clinical practice and, despite its profound impact on patients’ quality of life, it is often underestimated.48

Although some symptoms, such as fatigue and sleep disturbances, were common in both cancer patients and cardiovascular disease patients, underlying mechanisms and clinical manifestations may differ, reinforcing the idea of individualized detection.

Another noteworthy finding is that between 25% and 35% of patients had a UMPN score in the items feeling sleepy during the day, feeling restless and/or agitated, weight loss or gain, and sleep disturbances at night. This is consistent with what has been described in the literature, in which it has been established that chronic diseases often cause poor health outcomes that, in turn, are related to a poor quality of life.49

Cancer and its treatment can cause changes in people’s physical appearance, leading to a negative body image and psychosocial issues,39 while sleep disorders are common in patients with cardiovascular disease.50,51 In our study, the symptoms “being concerned about changes in appearance” and “problems sleeping at night” were rarely reported, but in both cases they were more prevalent in the cancer group, which could be related to clinical underestimation, self-reporting, or normalization of discomfort, thus raising the need for future studies to further explore this difference.

Our results stem from a broad sample of inpatients predominantly diagnosed with cardiovascular diseases, offering a perspective closer to the reality of inpatient care and underscoring the need to integrate the systematic assessment of the most prevalent UMPNs into this level of care.

The detection of UMPNs must be supported by a response from PC services. Although evidence of its benefits has focused on cancer (with proven improvements in the control of symptoms such as pain, dyspnea, fatigue, and nausea, as well as in quality of life and patient satisfaction),37,38,42,43 the implementation of PC in patients with chronic non-oncologic diseases is also critical.52 On this point, in a systematic review and meta-analysis that included 28 randomized clinical trials (13 664 patients in total, mostly with non-cancer diseases), Quinn et al.35 found that, compared with usual care, the implementation of PC was significantly associated with less emergency department use, less hospitalization, and a slightly lower symptom burden. In this sense, the results of our study, which report the frequency and nature of UMPNs, can help plan the implementation of PC for cancer and cardiovascular disease patients, especially the latter, because even though we included individuals with cancer, most (+70%) had cardiovascular diseases.

This study has several limitations that should be considered. First, convenience sampling of patients in a high-complexity hospital may reduce the validity of the results by introducing potential selection biases toward cases with a higher symptom burden, although our objective was exploratory and aimed to demonstrate the existence of these UMPNs through systematic and standardized methods. Second, for participants with low levels of education or visual impairments, it was necessary to administer the instrument with assistance, which creates a risk of bias in the interviewer and a social desirability bias in the participants, especially on sensitive items such as perception of symptom control, memory, or mood; however, to minimize these risks, standardized training was provided to interviewers, neutral scripts were used, and privacy and continuous supervision were facilitated, although this does not rule out residual bias. Third, its cross-sectional and self-report design limits the ability of capturing the temporal variability of needs during hospitalization. Fourth, the length of the questionnaire may have caused respondent fatigue and, therefore, data may be missing. Finally, our analysis was based on a comparison between patients with two main diagnostic groups, so it is not possible to identify differences by specific diseases; in this regard, future research could explore specific differences by disease in greater depth using targeted or stratified designs.

Conclusions

Most patients admitted to a university hospital in Popayán due to cancer or chronic cardiovascular diseases presented with UMPNs, with cancer patients being the most affected, as the median of UMPNs was significantly higher in this group. Also, in 18 of the 21 items of the Physical Symptoms domain of the SPARC-Sp, the proportion of patients in whom the presence of UMPNs was identified was higher in this group compared to the cardiovascular diseases group. Pain was the most common UMPN. The high burden of UMPNs, especially in cancer patients, stresses the need to integrate systematic assessments into PC to optimize clinical response and reduce avoidable suffering.

Conflicts of interest

None stated by the authors.

Funding

None stated by the authors.

Acknowledgements

To Gillian Prue, Tracey McConnell, and Joanne Reid, for their active participation in the Colibrí project, Decisiones médicas en el final de la vida en pacientes oncológicos en Colombia (Medical decisions at the end of life in cancer patients in Colombia), which was the basis for conceiving this study and establishing its methodology.

Referencias

1.Radbruch L, De Lima L, Knaul F, Wenk R, Ali Z, Bhatnaghar S, et al. Redefining Palliative Care-A New Consensus-Based Definition. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(4):754-64. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.027. PMID: 32387576; PMCID: PMC8096724.

2.Knaul FM, Farmer PE, Krakauer EL, De Lima L, Bhadelia A, Jiang-Kwete X, et al. Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief—an imperative of universal health coverage: the Lancet Commission report. The Lancet. 2018;391(10128):1391-454. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32513-8. Erratum in: Lancet. 2018;391(10136):2212. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30616-0. PMID: 29032993.

3.World Health Organization (WHO). Health in 2015: from MDGs, Millennium Development Goals to SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2015 [cited 2025 Jan 30]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/200009.

4.Sleeman KE, de Brito M, Etkind S, Nkhoma K, Guo P, Higginson IJ, et al. The escalating global burden of serious health-related suffering: projections to 2060 by world regions, age groups, and health conditions. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(7):e883-e892. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30172-X. PMID: 31129125; PMCID: PMC6560023.

5.Calvache JA, Gil F, de Vries E. How many people need palliative care for cancer and non-cancer diseases in a middle-income country? Analysis of mortality data. Colomb J Anesthesiol. 2020;48(4). doi: 10.1097/CJ9.0000000000000159.

6.Pinedo-Torres I, Intimayta-Escalante C, Jara-Cuadros D, Yañez-Camacho W, Zegarra-Lizana P, Saire-Huamán R. Association between the need for palliative care and chronic diseases in patients treated in a peruvian hospital. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2021;38(4):569-76. doi: 10.17843/rpmesp.2021.384.9288. PMID: 35385009.

7.Antonione R, Nodari S, Fieramosca M. Criteri di selezione del malato con scompenso cardiaco da avviare a cure palliative [Selection criteria to palliative care implementation in advanced heart failure]. G Ital Cardiol (Rome). 2020;21(4):272-7. Italian. doi: 10.1714/3328.32987. PMID: 32202559.

8.Boje J, Madsen JK, Finderup J. Palliative care needs experienced by Danish patients with end-stage kidney disease. J Ren Care. 2021;47(3):169-83. doi: 10.1111/jorc.12347. PMID: 32865343.

9.Colombia. Congreso de la República. Ley 1733 de 2014 (septiembre 8): Ley Consuelo Devis Saavedra, mediante la cual se regulan los servicios de cuidados paliativos para el manejo integral de pacientes con enfermedades terminales, crónicas, degenerativas e irreversibles en cualquier fase de la enfermedad de alto impacto en la calidad de vida. Bogotá D.C.: Diario Oficial 49268; September 8 2014.

10.Colombia. Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social (Minsalud), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS). Guía de Práctica Clínica para la atención de pacientes en cuidado paliativo (adopción) [Internet]. Bogotá D.C.: Minsalud; 2016 [cited 2025 Aug 27]. Available from: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/DE/CA/gpc-completa-cuidados-paliativos-adopcion.pdf.

11. Sánchez-Cárdenas MA, Cañón-Piñeros ÁM, López Moreno M. Estado actual de los cuidados paliativos de Colombia. Reporte técnico 2024 [Internet]. Bogotá D.C.: Observatorio Colombiano de Cuidados Paliativos; 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 13]. Available from: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12495/14250.

12.Colombia. Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social (Minsalud). Análisis de Situación de Salud (ASIS) Colombia, 2019. Bogotá D.C.: Minsalud; 2020 [cited 2025 Sep 17]. Available from: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/lists/bibliotecadigital/ride/vs/ed/psp/asis-2019-colombia.pdf.

13.GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1204-22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9. Erratum in: Lancet. 2020;396(10262):1562. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32226-1. PMID: 33069326; PMCID: PMC7567026.

14.Arenare L, Di Liello R, De Placido P, Gridelli C, Morabito A, Pignata S, et al. Under-reporting of subjective symptoms and its prognostic value: a pooled analysis of 12 cancer clinical trials. ESMO Open. 2024;9(3):102941. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.102941. Erratum in: ESMO Open. 2024;9(11):103693. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103693. PMID: 38452437; PMCID: PMC10937229.

15.Yang LY, Manhas DS, Howard AF, Olson RA. Patient-reported outcome use in oncology: a systematic review of the impact on patient-clinician communication. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(1):41-60. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3865-7. PMID: 28849277.

16.Casaca P, Schäfer W, Nunes AB, Sousa P. Using patient-reported outcome measures and patient-reported experience measures to elevate the quality of healthcare. Int J Qual Health Care. 2023;35(4):mzad098. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzad098. PMID: 38113907; PMCID: PMC10750971.

17.Nikkhah J, Steinbeck V, Grobe TG, Breitkreuz T, Pross C, Busse R. Evaluating the Population-Based Usage and Benefit of Digitally Collected Patient-Reported Outcomes and Experiences in Patients With Chronic Diseases: The PROMchronic Study Protocol. JMIR Res Protoc. 2024;13:e56487. doi: 10.2196/56487. PMID: 39102279; PMCID: PMC11333866.

18.Mendieta CV, Calvache JA, Rondón MA, Rincón-Rodríguez CJ, Ahmedzai SH, de Vries E. Validation of the Spanish translation Sheffield Profile for Assessment and Referral for Care (SPARC-Sp) at the Hospital Universitario San Jose of Popayan, Colombia. Palliat Support Care. 2024;22(5):1282-93. doi: 10.1017/S1478951524000476. PMID: 38533614.

19.Moreno S, Mendieta CV, de Vries E, Ahmedzai SH, Rivera K, Cortes-Mora C, et al. Translation and linguistic validation of the Sheffield Profile for Assessment and Referral for Care (SPARC) to Colombian Spanish. Palliat Support Care. 2024;1-10. doi: 10.1017/S1478951524000038. PMID: 38327224.

20.Hughes P, Ahmed N, Winslow M, Walters SJ, Collins K, Noble B. Consumer views on a new holistic screening tool for supportive and palliative‐care needs: Sheffield Profile for Assessment and Referral for Care (SPARC): a survey of self‐help support groups in health care. Health Expect. 2015;18(4):562-77. doi: 10.1111/hex.12058. PMID: 23414548; PMCID: PMC5060805.

21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). About Chronic Diseases [Internet]. Atlanta: CDC; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 27]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/chronic-disease/about/index.html.

22.World Health Organization (WHO). Non communicable diseases [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 27]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases.

23.Khalid MA, Achakzai IK, Ahmed Khan S, Majid Z, Hanif FM, Iqbal J, et al. The use of Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) as a predictor of 3 month post discharge mortality in cirrhotic patients. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2018;11(4):301-5. PMID: 30425808; PMCID: PMC6204247.

24.Stedman MR, Watford DJ, Chertow GM, Tan JC. Karnofsky Performance Score-Failure to Thrive as a Frailty Proxy? Transplant Direct. 2021;7(7):e708. doi: 10.1097/TXD.0000000000001164. PMID: 34124344; PMCID: PMC8191697.

25.U.S. Departamento f Veterans Affairs. Karnofsky Performance Scale [Internet]. Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; 2019 [cited 2025 Sep 3]. Available from: https://www.hiv.va.gov/provider/tools/karnofsky-performance-scale.asp.

26.MDCalc. Karnofsky Performance Status Scale [Internet]. MDCalcs; [cited 2025 Sep 3]. Available from: https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/3168/karnofsky-performance-status-scale#why-use.

27.Martin RC, Gerstenecker A, Nabors LB, Marson DC, Triebel KL. Impairment of medical decisional capacity in relation to Karnofsky Performance Status in adults with malignant brain tumor. Neurooncol Pract. 2015;2(1):13-9. doi: 10.1093/nop/npu030. PMID: 26034637; PMCID: PMC4369704.

28.Timmermann C. 'Just give me the best quality of life questionnaire': the Karnofsky scale and the history of quality of life measurements in cancer trials. Chronic Illn. 2013;9(3):179-90. doi: 10.1177/1742395312466903. PMID: 23239756; PMCID: PMC3837542.

29.Zar JH. Biostatistical analysis. 5th ed. Upper Saddle River, N.J: Pearson Education Limited; 2014.

30.RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R [Software]. RStudio Team; 2022.

31.World Medical Association (WMA). WMA Declaration of Helsinki - Ethical principles for medical research involving human participants [Internet]. Helsinki: 75th WMA General Assembly; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 27]. Available from: https://bit.ly/40k4BRS.

32.Colombia. Ministerio de Salud. Resolución 8430 de 1993 (octubre 4): Por la cual se establecen las normas científicas, técnicas y administrativas para la investigación en salud [Internet]. Bogotá D.C.; October 4 1993 [cited 2025 Aug 27]. Available from: https://bit.ly/3Q3R0t8.

33.Vega-Vega P, González-Rodriguez R, López-Ramirez M, Miranda-Castillo C. Integración temprana de cuidados paliativos; implicancias para personas con enfermedades crónicas [Early integration of palliative care; implications for people with chronic diseases]. Rev Med Chil. 2024;152(1):102-10. Spanish. doi: 10.4067/s0034-98872024000100102. PMID: 39270101.

34.Schlau H. Frühe Integration der Palliative Care - eine Begriffsbestimmung für die Praxis [Early Integration of Palliative Care - A Definition for Daily Practice]. Praxis (Bern 1994). 2021;110(15):855-60. German. doi: 10.1024/1661-8157/a003791. PMID: 34814727.

35.Quinn KL, Shurrab M, Gitau K, Kavalieratos D, Isenberg SR, Stall NM, et al. Association of Receipt of Palliative Care Interventions With Health Care Use, Quality of Life, and Symptom Burden Among Adults With Chronic Noncancer Illness: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020;324(14):1439-50. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.14205. PMID: 33048152; PMCID: PMC8094426.

36.Liu Y, Tao L, Liu M, Ma L, Xu Y, Zhao C. The impact of palliative care on the physical and mental status and quality of life of patients with chronic heart failure: A randomized controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102(50):e36607. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000036607. PMID: 38115251; PMCID: PMC10727569.

37.Mestdagh F, Steyaert A, Lavand’homme P. Cancer Pain Management: A Narrative Review of Current Concepts, Strategies, and Techniques. Curr Oncol. 2023;30(7):6838-58. doi: 10.3390/curroncol30070500. PMID: 37504360; PMCID: PMC10378332.

38.Bhatt K, Palomares AC, Forget P, Ryan D; Societal Impact of Pain (SIP) platform. Importance of pain management in cancer patients and survivors. Ann Oncol. 2024;35(5):473-4. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2024.01.006. PMID: 38311208.

39.Milky MN. Living with an Altered Body: A Qualitative Account of Body Image with Cancer Diagnosis and Its Treatment Among Women in Kolkata, West Bengal, India. The Qualitative Report. 2024;29(5):1472-95. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2024.5378.

40.Glare PA, Pugliano L, Sequeira AA, Asghari A, Nicholas MK. Psychosocial factors contribute to the disability and distress associated with chronic pain in ambulatory patients attending an Australian cancer center. Research Square. 2024. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-4037302/v1.

41.Dave P. Recommendations for Pain Management in Cancer Patients. Asian J Pharm Res Dev. 2024;12(2):7-12. doi: 10.22270/ajprd.v12i2.1339.

42.Henson LA, Maddocks M, Evans C, Davidson M, Hicks S, Higginson IJ. Palliative Care and the Management of Common Distressing Symptoms in Advanced Cancer: Pain, Breathlessness, Nausea and Vomiting, and Fatigue. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(9):905-14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00470. PMID: 32023162; PMCID: PMC7082153.

43.Tagami K, Chiu SW, Kosugi K, Ishiki H, Hiratsuka Y, Shimizu M, et al. Cancer Pain Management in Patients Receiving Inpatient Specialized Palliative Care Services. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2024;67(1):27-38.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2023.09.015. PMID: 37730073.

44.Layne-Stuart CM, Carpenter AL. Chronic Pain Considerations in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. Anesthesiol Clin. 2022;40(4):791-802. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2022.08.018. PMID: 36328629.

45.Vikan KK, Landmark T, Gjeilo KH. Prevalence of chronic pain and chronic widespread pain among subjects with heart failure in the general population: The HUNT study. Eur J Pain. 2024;28(2):273-84. doi: 10.1002/ejp.2176. PMID: 37680005.

46.Warlo LS, El Bardai S, de Vries A, van Veelen ML, Moors S, Rings EH, et al. Game-Based eHealth Interventions for the Reduction of Fatigue in People With Chronic Diseases: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JMIR Serious Games. 2024;12:e55034. doi: 10.2196/55034. PMID: 39419502; PMCID: PMC11528177.

47.Goërtz YMJ, Braamse AMJ, Spruit MA, Janssen DJA, Ebadi Z, Van Herck M, et al. Fatigue in patients with chronic disease: results from the population-based Lifelines Cohort Study. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):20977. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-00337-z. PMID: 34697347; PMCID: PMC8546086.

48.Al Maqbali M, Al Sinani M, Al Naamani Z, Al Badi K, Tanash MI. Prevalence of Fatigue in Patients With Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;61(1):167-189.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.07.037. PMID: 32768552.

49.Bahall M, Bailey H. The impact of chronic disease and accompanying bio-psycho-social factors on health-related quality of life. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2022;11(8):4694-704. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_2399_21. PMID: 36352993; PMCID: PMC9638608.

50.Zhang L, Li G, Bao Y, Liu M. Role of sleep disorders in patients with cardiovascular disease: A systematic review. Int J Cardiol Cardiovasc Risk Prev. 2024;21:200257. PMID: 38549735; PMCID: PMC10972826.

51.Yarlioglues M, Karacali K, Ilhan BC, Yalcinkaya-Oner D. An observational study: The relationship between sleep quality and angiographic progression in patients with chronic coronary artery disease. Sleep Med. 2024;116:56-61. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2024.02.039. PMID: 38428343.

52.Tziraki C, Grimes C, Ventura F, O’Caoimh R, Santana S, Zavagli V, et al. Rethinking palliative care in a public health context: addressing the needs of persons with non-communicable chronic diseases. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2020;21:e60. doi: 10.1017/S1463423620000602. PMID: 32928334; PMCID: PMC7503185.

Annex 1

Data collection form used in the study.

Annex 2

Spanish version of the Sheffield Profile for Assessment and Referral for Care (SPARC-Sp) questionnaire validated for use in the Colombian population.

Referencias

1. Radbruch L, De Lima L, Knaul F, Wenk R, Ali Z, Bhatnaghar S, et al. Redefining Palliative Care-A New Consensus-Based Definition. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(4):754-64. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.027. PMID: 32387576; PMCID: PMC8096724.

2. Knaul FM, Farmer PE, Krakauer EL, De Lima L, Bhadelia A, Jiang-Kwete X, et al. Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief—an imperative of universal health coverage: the Lancet Commission report. The Lancet. 2018;391(10128):1391-454. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32513-8. Erratum in: Lancet. 2018;391(10136):2212. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30616-0. PMID: 29032993.

3. World Health Organization (WHO). Health in 2015: from MDGs, Millennium Development Goals to SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2015 [cited 2025 Jan 30]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/200009.

4. Sleeman KE, de Brito M, Etkind S, Nkhoma K, Guo P, Higginson IJ, et al. The escalating global burden of serious health-related suffering: projections to 2060 by world regions, age groups, and health conditions. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(7):e883-e892. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30172-X. PMID: 31129125; PMCID: PMC6560023.

5. Calvache JA, Gil F, de Vries E. How many people need palliative care for cancer and non-cancer diseases in a middle-income country? Analysis of mortality data. Colomb J Anesthesiol. 2020;48(4). doi: 10.1097/CJ9.0000000000000159.

6. Pinedo-Torres I, Intimayta-Escalante C, Jara-Cuadros D, Yañez-Camacho W, Zegarra-Lizana P, Saire-Huamán R. Association between the need for palliative care and chronic diseases in patients treated in a peruvian hospital. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2021;38(4):569-76. doi: 10.17843/rpmesp.2021.384.9288. PMID: 35385009.

7. Antonione R, Nodari S, Fieramosca M. Criteri di selezione del malato con scompenso cardiaco da avviare a cure palliative [Selection criteria to palliative care implementation in advanced heart failure]. G Ital Cardiol (Rome). 2020;21(4):272-7. Italian. doi: 10.1714/3328.32987. PMID: 32202559.

8. Boje J, Madsen JK, Finderup J. Palliative care needs experienced by Danish patients with end-stage kidney disease. J Ren Care. 2021;47(3):169-83. doi: 10.1111/jorc.12347. PMID: 32865343.

9. Colombia. Congreso de la República. Ley 1733 de 2014 (septiembre 8): Ley Consuelo Devis Saavedra, mediante la cual se regulan los servicios de cuidados paliativos para el manejo integral de pacientes con enfermedades terminales, crónicas, degenerativas e irreversibles en cualquier fase de la enfermedad de alto impacto en la calidad de vida. Bogotá D.C.: Diario Oficial 49268; September 8 2014.

10. Colombia. Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social (Minsalud), Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS). Guía de Práctica Clínica para la atención de pacientes en cuidado paliativo (adopción) [Internet]. Bogotá D.C.: Minsalud; 2016 [cited 2025 Aug 27]. Available from: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/DE/CA/gpc-completa-cuidados-paliativos-adopcion.pdf.

11. Sánchez-Cárdenas MA, Cañón-Piñeros ÁM, López Moreno M. Estado actual de los cuidados paliativos de Colombia. Reporte técnico 2024 [Internet]. Bogotá D.C.: Observatorio Colombiano de Cuidados Paliativos; 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 13]. Available from: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12495/14250.

12. Colombia. Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social (Minsalud). Análisis de Situación de Salud (ASIS) Colombia, 2019. Bogotá D.C.: Minsalud; 2020 [cited 2025 Sep 17]. Available from: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/lists/bibliotecadigital/ride/vs/ed/psp/asis-2019-colombia.pdf.

13. GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1204-22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9. Erratum in: Lancet. 2020;396(10262):1562. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32226-1. PMID: 33069326; PMCID: PMC7567026.

14. Arenare L, Di Liello R, De Placido P, Gridelli C, Morabito A, Pignata S, et al. Under-reporting of subjective symptoms and its prognostic value: a pooled analysis of 12 cancer clinical trials. ESMO Open. 2024;9(3):102941. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.102941. Erratum in: ESMO Open. 2024;9(11):103693. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103693. PMID: 38452437; PMCID: PMC10937229.

15. Yang LY, Manhas DS, Howard AF, Olson RA. Patient-reported outcome use in oncology: a systematic review of the impact on patient-clinician communication. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(1):41-60. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3865-7. PMID: 28849277.

16. Casaca P, Schäfer W, Nunes AB, Sousa P. Using patient-reported outcome measures and patient-reported experience measures to elevate the quality of healthcare. Int J Qual Health Care. 2023;35(4):mzad098. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzad098. PMID: 38113907; PMCID: PMC10750971.

17. Nikkhah J, Steinbeck V, Grobe TG, Breitkreuz T, Pross C, Busse R. Evaluating the Population-Based Usage and Benefit of Digitally Collected Patient-Reported Outcomes and Experiences in Patients With Chronic Diseases: The PROMchronic Study Protocol. JMIR Res Protoc. 2024;13:e56487. doi: 10.2196/56487. PMID: 39102279; PMCID: PMC11333866.

18. Mendieta CV, Calvache JA, Rondón MA, Rincón-Rodríguez CJ, Ahmedzai SH, de Vries E. Validation of the Spanish translation Sheffield Profile for Assessment and Referral for Care (SPARC-Sp) at the Hospital Universitario San Jose of Popayan, Colombia. Palliat Support Care. 2024;22(5):1282-93. doi: 10.1017/S1478951524000476. PMID: 38533614.

19. Moreno S, Mendieta CV, de Vries E, Ahmedzai SH, Rivera K, Cortes-Mora C, et al. Translation and linguistic validation of the Sheffield Profile for Assessment and Referral for Care (SPARC) to Colombian Spanish. Palliat Support Care. 2024;1-10. doi: 10.1017/S1478951524000038. PMID: 38327224.

20. Hughes P, Ahmed N, Winslow M, Walters SJ, Collins K, Noble B. Consumer views on a new holistic screening tool for supportive and palliative‐care needs: Sheffield Profile for Assessment and Referral for Care (SPARC): a survey of self‐help support groups in health care. Health Expect. 2015;18(4):562-77. doi: 10.1111/hex.12058. PMID: 23414548; PMCID: PMC5060805.

21. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). About Chronic Diseases [Internet]. Atlanta: CDC; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 27]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/chronic-disease/about/index.html.

22. World Health Organization (WHO). Non communicable diseases [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 27]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases.

23. Khalid MA, Achakzai IK, Ahmed Khan S, Majid Z, Hanif FM, Iqbal J, et al. The use of Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) as a predictor of 3 month post discharge mortality in cirrhotic patients. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2018;11(4):301-5. PMID: 30425808; PMCID: PMC6204247.

24. Stedman MR, Watford DJ, Chertow GM, Tan JC. Karnofsky Performance Score-Failure to Thrive as a Frailty Proxy? Transplant Direct. 2021;7(7):e708. doi: 10.1097/TXD.0000000000001164. PMID: 34124344; PMCID: PMC8191697.

25. U.S. Departamento f Veterans Affairs. Karnofsky Performance Scale [Internet]. Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; 2019 [cited 2025 Sep 3]. Available from: https://www.hiv.va.gov/provider/tools/karnofsky-performance-scale.asp.

26. MDCalc. Karnofsky Performance Status Scale [Internet]. MDCalcs; [cited 2025 Sep 3]. Available from: https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/3168/karnofsky-performance-status-scale#why-use.

27. Martin RC, Gerstenecker A, Nabors LB, Marson DC, Triebel KL. Impairment of medical decisional capacity in relation to Karnofsky Performance Status in adults with malignant brain tumor. Neurooncol Pract. 2015;2(1):13-9. doi: 10.1093/nop/npu030. PMID: 26034637; PMCID: PMC4369704.

28. Timmermann C. 'Just give me the best quality of life questionnaire': the Karnofsky scale and the history of quality of life measurements in cancer trials. Chronic Illn. 2013;9(3):179-90. doi: 10.1177/1742395312466903. PMID: 23239756; PMCID: PMC3837542.

29. Zar JH. Biostatistical analysis. 5th ed. Upper Saddle River, N.J: Pearson Education Limited; 2014.

30. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R [Software]. RStudio Team; 2022.

31. World Medical Association (WMA). WMA Declaration of Helsinki - Ethical principles for medical research involving human participants [Internet]. Helsinki: 75th WMA General Assembly; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 27]. Available from: https://bit.ly/40k4BRS.

32. Colombia. Ministerio de Salud. Resolución 8430 de 1993 (octubre 4): Por la cual se establecen las normas científicas, técnicas y administrativas para la investigación en salud [Internet]. Bogotá D.C.; October 4 1993 [cited 2025 Aug 27]. Available from: https://bit.ly/3Q3R0t8.

33. Vega-Vega P, González-Rodriguez R, López-Ramirez M, Miranda-Castillo C. Integración temprana de cuidados paliativos; implicancias para personas con enfermedades crónicas [Early integration of palliative care; implications for people with chronic diseases]. Rev Med Chil. 2024;152(1):102-10. Spanish. doi: 10.4067/s0034-98872024000100102. PMID: 39270101.

34. Schlau H. Frühe Integration der Palliative Care - eine Begriffsbestimmung für die Praxis [Early Integration of Palliative Care - A Definition for Daily Practice]. Praxis (Bern 1994). 2021;110(15):855-60. German. doi: 10.1024/1661-8157/a003791. PMID: 34814727.

35. Quinn KL, Shurrab M, Gitau K, Kavalieratos D, Isenberg SR, Stall NM, et al. Association of Receipt of Palliative Care Interventions With Health Care Use, Quality of Life, and Symptom Burden Among Adults With Chronic Noncancer Illness: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020;324(14):1439-50. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.14205. PMID: 33048152; PMCID: PMC8094426.

36. Liu Y, Tao L, Liu M, Ma L, Xu Y, Zhao C. The impact of palliative care on the physical and mental status and quality of life of patients with chronic heart failure: A randomized controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102(50):e36607. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000036607. PMID: 38115251; PMCID: PMC10727569.

37. Mestdagh F, Steyaert A, Lavand’homme P. Cancer Pain Management: A Narrative Review of Current Concepts, Strategies, and Techniques. Curr Oncol. 2023;30(7):6838-58. doi: 10.3390/curroncol30070500. PMID: 37504360; PMCID: PMC10378332.

38. Bhatt K, Palomares AC, Forget P, Ryan D; Societal Impact of Pain (SIP) platform. Importance of pain management in cancer patients and survivors. Ann Oncol. 2024;35(5):473-4. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2024.01.006. PMID: 38311208.

39. Milky MN. Living with an Altered Body: A Qualitative Account of Body Image with Cancer Diagnosis and Its Treatment Among Women in Kolkata, West Bengal, India. The Qualitative Report. 2024;29(5):1472-95. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2024.5378.

40. Glare PA, Pugliano L, Sequeira AA, Asghari A, Nicholas MK. Psychosocial factors contribute to the disability and distress associated with chronic pain in ambulatory patients attending an Australian cancer center. Research Square. 2024. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-4037302/v1.

41. Dave P. Recommendations for Pain Management in Cancer Patients. Asian J Pharm Res Dev. 2024;12(2):7-12. doi: 10.22270/ajprd.v12i2.1339.

42. Henson LA, Maddocks M, Evans C, Davidson M, Hicks S, Higginson IJ. Palliative Care and the Management of Common Distressing Symptoms in Advanced Cancer: Pain, Breathlessness, Nausea and Vomiting, and Fatigue. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(9):905-14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00470. PMID: 32023162; PMCID: PMC7082153.

43. Tagami K, Chiu SW, Kosugi K, Ishiki H, Hiratsuka Y, Shimizu M, et al. Cancer Pain Management in Patients Receiving Inpatient Specialized Palliative Care Services. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2024;67(1):27-38.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2023.09.015. PMID: 37730073.

44. Layne-Stuart CM, Carpenter AL. Chronic Pain Considerations in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. Anesthesiol Clin. 2022;40(4):791-802. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2022.08.018. PMID: 36328629.

45. Vikan KK, Landmark T, Gjeilo KH. Prevalence of chronic pain and chronic widespread pain among subjects with heart failure in the general population: The HUNT study. Eur J Pain. 2024;28(2):273-84. doi: 10.1002/ejp.2176. PMID: 37680005.

46. Warlo LS, El Bardai S, de Vries A, van Veelen ML, Moors S, Rings EH, et al. Game-Based eHealth Interventions for the Reduction of Fatigue in People With Chronic Diseases: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JMIR Serious Games. 2024;12:e55034. doi: 10.2196/55034. PMID: 39419502; PMCID: PMC11528177.

47. Goërtz YMJ, Braamse AMJ, Spruit MA, Janssen DJA, Ebadi Z, Van Herck M, et al. Fatigue in patients with chronic disease: results from the population-based Lifelines Cohort Study. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):20977. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-00337-z. PMID: 34697347; PMCID: PMC8546086.

48. Al Maqbali M, Al Sinani M, Al Naamani Z, Al Badi K, Tanash MI. Prevalence of Fatigue in Patients With Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;61(1):167-189.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.07.037. PMID: 32768552.

49. Bahall M, Bailey H. The impact of chronic disease and accompanying bio-psycho-social factors on health-related quality of life. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2022;11(8):4694-704. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_2399_21. PMID: 36352993; PMCID: PMC9638608.

50. Zhang L, Li G, Bao Y, Liu M. Role of sleep disorders in patients with cardiovascular disease: A systematic review. Int J Cardiol Cardiovasc Risk Prev. 2024;21:200257. PMID: 38549735; PMCID: PMC10972826.

51. Yarlioglues M, Karacali K, Ilhan BC, Yalcinkaya-Oner D. An observational study: The relationship between sleep quality and angiographic progression in patients with chronic coronary artery disease. Sleep Med. 2024;116:56-61. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2024.02.039. PMID: 38428343.

52. Tziraki C, Grimes C, Ventura F, O’Caoimh R, Santana S, Zavagli V, et al. Rethinking palliative care in a public health context: addressing the needs of persons with non-communicable chronic diseases. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2020;21:e60. doi: 10.1017/S1463423620000602. PMID: 32928334; PMCID: PMC7503185.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Licencia

Derechos de autor 2025 El(Los) autor(es).

Esta obra está bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons Atribución 4.0.

-