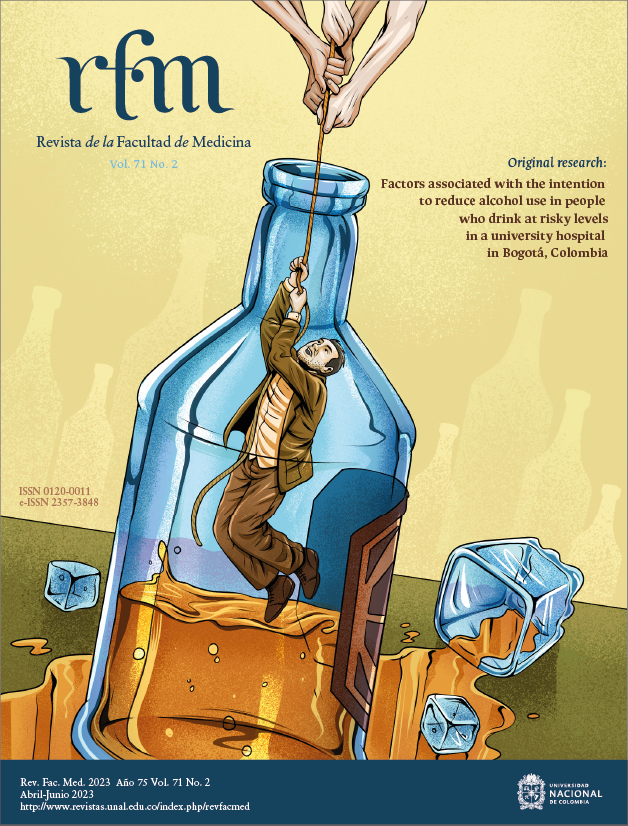

Alcohol abuse: a major invisible pandemic

El consumo de alcohol: una gran pandemia invisible

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/revfacmed.v71n2.110823Keywords:

Public Health, Alcohol Abuse (en)Salud Pública, Alcoholismo (es)

Between 2011 and 2021, the number of drug users increased by 23%, going from 240 million to 296 million.1 In this context, alcohol abuse is a risk factor for over 200 health disorders. According to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), the rate of alcohol use in the Americas is approximately 40% higher in the Americas than the global average, which means that this population consumes alcohol in a manner that is detrimental to their health. Therefore, among the numerous psychoactive substances available, alcohol is the main risk factor for burden of disease.2

Entre 2011 y 2021, el número de usuarios de drogas aumentó 23%, pasando de 240 millones a 296 millones.1 El consumo de alcohol es un factor de riesgo para más de 200 trastornos de salud. En América, según la Organización Panamericana de la Salud (OPS), dicha práctica es aproximadamente 40% más alta que el promedio mundial, lo que significa que esta población consume alcohol en un patrón peligroso para la salud y por tanto, entre las diversas sustancias psicoactivas consumidas, este es el principal factor de riesgo para la carga de la enfermedad. 2

editorial

Alcohol abuse: a major invisible pandemic

El consumo de alcohol: una gran pandemia invisible

Open access

How to cite: Cote-Menéndez M. Alcohol abuse: a major invisible pandemic. Rev. Fac. Med. 2023;71(2):e110823. English. doi: https://doi.org/10.15446/revfacmed.v71n2.110823.

Cómo citar: Cote-Menéndez M. [El consumo de alcohol: la gran pandemia invisible]. Rev. Fac. Med. 2023;71(2):e110823. English. doi: https://doi.org/10.15446/revfacmed.v71n2.110823.

Copyright: Copyright: ©2022 Universidad Nacional de Colombia. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, as long as the original author and source are credited.

Between 2011 and 2021, the number of drug users increased by 23%, going from 240 million to 296 million.1 In this context, alcohol abuse is a risk factor for over 200 health disorders. According to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), the rate of alcohol use in the Americas is approximately 40% higher in the Americas than the global average, which means that this population consumes alcohol in a manner that is detrimental to their health. Therefore, among the numerous psychoactive substances available, alcohol is the main risk factor for burden of disease.2

In Bogotá (Colombia), alcohol use, as reported by the Observatorio de Salud,3 increased by 3.4% among current consumers, rising from 36.5% in 2016 to 39.01% in 2022. Furthermore, the same organization reports that this increased prevalence is found in both men and women of all age groups and across all socioeconomic levels.3 Regarding age, the highest prevalence of alcohol use is found in the 25-34 age group (39.7%), followed by the 18-24 age group (38.3%); these two groups show significantly higher figures than the other age segments, with the 12-17 age group having the lowest consumption rate (12.1%).4

Beer is the most popular alcoholic beverage among Colombians, with a prevalence of 24.7%, followed by aguardiente (distilled spirit made from sugar cane and aniseed) with 8.2%, and rum with 5.5%, which may explain why people in many regions of the country believe that drinking beer poses no health risks, unlike other alcoholic beverages such as rum, aguardiente, or whiskey. This situation has normalized risky alcohol intake among the general population.

Alcohol is a psychoactive substance that works as a central nervous system depressant and, consequently, affects brain activity. In this sense, excessive alcohol consumption causes behavioral problems and mental changes related to social and economic problems that have an impact not only on the consumers themselves, but also on the people around them.

Monteiro5 has suggested the need to consider alcohol use as a priority issue for public health care in the Americas and to initiate actions to control its abuse. Evidence-based research shows, as mentioned above, that alcohol use and drinking patterns in the region are already at harmful levels and that they exceed global averages for many alcohol-related problems. Monteiro5 also states that there are several public health policies for reducing alcohol use that have been implemented and evaluated in different countries and cultures that have proven to be effective.

Heavy episodic drinking, defined as the consumption of 5 or more standard drinks per occasion (or for a two-hour period) of any alcoholic beverage containing an equivalent of 10g of pure alcohol for men and 4 or more standard drinks per occasion for women, is a pattern of alcohol use associated with increased physical and emotional harm, and with situations involving violence, accidents, unwanted pregnancies, unprotected sex, and sexually transmitted diseases.4 In this sense, excessive drinking is one of the main health risk factors for the population worldwide, having a direct impact on many of the targets set out in the Sustainable Development Goals,6 mainly those related to health and wellbeing.

In its Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2018, PAHO7 states that, following the development and ratification of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, alcohol is the only psychoactive and dependence-generating substance with a significant global impact on population health that is not controlled at the international level through binding legal standards. The same document also states that alcohol and public health monitoring and surveillance systems should cover three broad areas of key indicators, namely, those related to alcohol use, health and social consequences, and policy and programmatic responses. Thus, in order to monitor this situation worldwide, it is essential to have updated data from all countries.7

Concerning health outcomes, PAHO7 established that in 2016, harmful alcohol use caused nearly 3 million deaths (5.3% of all deaths) worldwide and 132.6 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), that is, 5.1% of all DALYs in that year. This means that mortality due to alcohol use is higher than mortality due to diseases such as tuberculosis, AIDS, and diabetes.

Excessive drinking is not the same among men and women: PAHO7 estimates that in 2016 about 2.3 million deaths and 106.5 million DALYs were attributable to drinking in men, while there were 0.7 million deaths and 26.1 million DALYs attributable to alcohol use in women. This situation demonstrates that alcohol abuse is normalized all over the world, which, in turn, proves the need to screen for people at risk of excessive alcohol use and people with the intention of reducing their consumption in order to control this public health issue.

Given this scenario, Cuevas et al.8 conducted a cross-sectional descriptive study in 176 adult patients (aged 19 to 64 years) with risky alcohol use (according to AUDIT score) treated or assessed between April 2018 and March 2020 at a quaternary care hospital in Bogotá D.C. The authors found a greater intention to reduce drinking in participants older than 30 years, in those with a greater perception of the benefits of such reduction, in those with a greater perception of self-efficacy, and in those who had previously made attempts to reduce their alcohol intake. Furthermore, the authors established that, in contrast, a higher socioeconomic level was associated with a lower intention to change.

Kaner et al.,9 in a review aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of screening and brief intervention to reduce heavy drinking in general practice or emergency care settings, found that brief interventions in primary care settings were more effective than usual care strategies, such as those in which only written information is shared.

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism10 states that men and women who drink more than 4 and 3 standard drinks in a day, respectively, are at increased risk for alcohol use disorders. These data are very useful for active searches and screening of persons at risk of excessive alcohol use, a process for which the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST),11 a test that analyzes all levels of problematic or risky substance use in adults, is recommended. This questionnaire is particularly convenient because it not only measures levels of alcohol use but of other substances that may affect human behavior. It is also easy to administer and can be completed in approximately 5-10 minutes, and all the resources for administering it are available online.

Screening for excessive alcohol use, as well as other psychoactive substances, is very important, as it has been demonstrated that this practice increased following the COVID-19 pandemic due to the social, economic and health problems it generated, so it is necessary to have data for designing strategies to control it.

Miguel Cote Menéndez

Full Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine,

Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Bogotá D.C., Colombia.

Director, Department of Toxicology, Faculty of Medicine,

Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá D.C., Colombia.

Coordinator, Mental Health Service, Hospital Universitario Nacional,

Bogotá D.C., Colombia.

mcotem@unal.edu.co

References

1.El número de consumidores de drogas aumentó un 23% en una década. Noticias ONU: Mirada global Historias humanas. June 25, 2023 [cited 2023 Jul 14]. Available from: https://bit.ly/3pNBF6A.

2.Organización Panamericana de la Salud (OPS). Alcohol. Washington D.C.: OPS; [cited 2023 Jul 14]. Available from: https://bit.ly/46M0Kzo.

3.SaluData Observatorio de Bogotá. .Prevalencia consumo actual de bebidas alcohólicas, tabaco y sustancias ilícitas en Bogotá D.C., 2022. Bogotá D.C.: Secretaría de Salud, Alaldía Mayor de Bogotá D.C.; 2023 [cited 2023 Jul 14 ]. Available from: https://bit.ly/44qXzLT.

4.Ministerio de Justicia y del Derecho, Observatorio de Drogas de Colombia (ODC). Estudio Nacional de Consumo de Sustancias Psicoactivas Colombia 2019. Bogotá DC.: ODC; 2019 [cited 2023 Jul 14]. Available from: https://bit.ly/3XZfN4L.

5.Monteiro MG. Alcohol y salud pública en las Américas: un caso para la acción. Washington D.C.: Organización Panamericana de la Salud; 2007.

6.Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS). Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible. Ginebra: OMS; 2015.

7.Organización Panamericana de la Salud (OPS). Informe sobre la situación mundial del alcohol y la salud 2018. Resumen. Washington D.C.: OPS; 2019

8.Cuevas V, Peñaloza M, Olejua P, Olaya L, Almonacid I, Alba LH. Factors associated with the intention to reduce alcohol use in people who drink at risky levels in a university hospital in Bogotá, Colombia. Rev. Fac. Med. 2022;71(2):e91270. https://doi.org/10.15446/revfacmed.v71n2.98969.

9.Kaner EF, Beyer FR, Muirhead C, Campbell F, Pienaar ED, Bertholet N, et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2(2):CD004148. https://doi.org/cnv5.

10.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A Clinician’s Guide. Updated 2005 Edition. NIAAA; 2007.

11.World Health Organization (WHO). The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST). Manual for use in primary care. Geneva: WHO; 2010.

References

El número de consumidores de drogas aumentó un 23% en una década. Noticias ONU: Mirada global Historias humanas. June 25, 2023 [cited 2023 Jul 14]. Available from: https://bit.ly/3pNBF6A.

Organización Panamericana de la Salud (OPS). Alcohol. Washington D.C.: OPS; [cited 2023 Jul 14]. Available from: https://bit.ly/46M0Kzo.

SaluData Observatorio de Bogotá. .Prevalencia consumo actual de bebidas alcohólicas, tabaco y sustancias ilícitas en Bogotá D.C., 2022. Bogotá D.C.: Secretaría de Salud, Alaldía Mayor de Bogotá D.C.; 2023 [cited 2023 Jul 14 ]. Available from: https://bit.ly/44qXzLT.

Ministerio de Justicia y del Derecho, Observatorio de Drogas de Colombia (ODC). Estudio Nacional de Consumo de Sustancias Psicoactivas Colombia 2019. Bogotá DC.: ODC; 2019 [cited 2023 Jul 14]. Available from: https://bit.ly/3XZfN4L.

Monteiro MG. Alcohol y salud pública en las Américas: un caso para la acción. Washington D.C.: Organización Panamericana de la Salud; 2007.

Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS). Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible. Ginebra: OMS; 2015.

Organización Panamericana de la Salud (OPS). Informe sobre la situación mundial del alcohol y la salud 2018. Resumen. Washington D.C.: OPS; 2019

Cuevas V, Peñaloza M, Olejua P, Olaya L, Almonacid I, Alba LH. Factors associated with the intention to reduce alcohol use in people who drink at risky levels in a university hospital in Bogotá, Colombia. Rev. Fac. Med. 2022;71(2):e91270. https://doi.org/10.15446/revfacmed.v71n2.98969. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15446/revfacmed.v71n2.98969

Kaner EF, Beyer FR, Muirhead C, Campbell F, Pienaar ED, Bertholet N, et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2(2):CD004148. https://doi.org/cnv5. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004148.pub4

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A Clinician’s Guide. Updated 2005 Edition. NIAAA; 2007.

World Health Organization (WHO). The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST). Manual for use in primary care. Geneva: WHO; 2010.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

License

Copyright (c) 2023 Revista de la Facultad de Medicina

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

Copyright

Authors must agree to transfer to the Revista de la Facultad de Medicina the copyright of the articles published in the Journal. The publisher has the right to use, reproduce, transmit, distribute and publish the articles in any form. Authors will not be able to permit or authorize the use of their published paper without the written consent of the Journal.

The letter of copyright transfer and the letter of authorship responsibility must be submitted along with the original paper through the Journal OJS platform. These files are available in https://goo.gl/EfWPdX y https://goo.gl/6zztk4 and must be uploaded in step 4 (supplementary files).

Authors who publish with this journal agree to the following terms:

- Authors retain copyright and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgement of the work's authorship and initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the journal's published version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgement of its initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See The Effect of Open Access).