Modeling the Motivations for Offshore Outsourcing: A Theoretical Approach

Caracterización de las motivaciones para la subcontratación offshore: un enfoque teórico

Caracterização das motivações para a subcontratação offshore: uma abordagem teórica

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/innovar.v28n68.70475Palabras clave:

tercerización en el extranjero, motivaciones, PYMES, empresas multinacionales (en)Offshore outsourcing, motivations, SMEs, mnes (es)

no exterior, motivações, PME, empresas multinacionais. (pt)

Offshore outsourcing by organizations has been gaining momentum, powered by advances in information technology and costs differentials. A review of the literature on the subject, though, shows that those scholars who have focused on offshore outsourcing have centered their attention on the activities of multinational enterprises (MNEs) in the manufacturing and services sectors, leaving behind small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Through a number of propositions, this paper suggests that SMEs could also benefit from offshore outsourcing given their particular characteristics and needs. The paper also discusses the similarities and differences in the motivations that SMEs might have in subcontracting their activities outside their boundaries in comparison to MNEs. Knowing this information is important for foreign suppliers in order to adapt and expand their offerings to the needs of these particular firms.

La subcontratación offshore por parte de las organizaciones ha venido consolidándose gracias a los avances en las tecnologías de la información y a las diferencias en costos que esta conlleva. No obstante, una revisión de literatura sobre el fenómeno señala que los estudiosos del tema han centrado su atención en las empresas multinacionales de los sectores de manufacturas y de servicios, dejando de lado a las pequeñas y medianas empresas (pyme). A través de la formulación de una serie de proposiciones, este documento sugiere que las pyme, debido a sus características y necesidades particulares, también podrían obtener beneficios de este modelo de tercerización. El documento discute además las similitudes y diferencias en las motivaciones de PYME y empresas multinacionales para subcontratar actividades más allá de sus fronteras. Esta información resulta ser importante para que proveedores en el extranjero puedan adaptar y ampliar su oferta con base en las necesidades de estas empresas.

A subcontratação offshore por parte das organizações tem se consolidado, graças às diferenças em custos que isso implica e aos avanços na tecnologia da informação. Porém, uma revisão de literatura sobre o fenômeno sinaliza que os estudiosos do tema centraram sua atenção nas empresas multinacionais dos setores de manufaturas e de serviços, sem considerar pequenas e médias empresas (pme). Através da formulação de uma série de proposições, este documento sugere que as pme, devido a suas características e necessidades particulares, também poderiam obter beneficios deste modelo de terceirização. O documento também discute as similaridades e diferenças nas motivações de PME e empresas multinacionais para subcontratar atividades além das suas fronteiras. Essa informação resulta ser importante para que fornecedores no exterior possam adaptar e ampliar a sua oferta com base nas necessidades dessas empresas.

Recibido: de diciembre de 2015; Aceptado: de marzo de 2017

ABSTRACT:

Offshore outsourcing by organizations has been gaining momentum, powered by advances in information technology and costs differentials. A review of the literature on the subject, though, shows that those scholars who have focused on offshore outsourcing have centered their attention on the activities of multinational enterprises (MNEs) in the manufacturing and services sectors, leaving behind small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Through a number of propositions, this paper suggests that SMEs could also benefit from offshore outsourcing given their particular characteristics and needs. The paper also discusses the similarities and differences in the motivations that SMEs might have in subcontracting their activities outside their boundaries in comparison to MNEs. Knowing this information is important for foreign suppliers in order to adapt and expand their offerings to the needs of these particular firms.

Clasificación JEL F23, F29, M16.

KEYWORDS:

Offshore outsourcing, motivations, SMEs, MNEs.RESUMEN:

La subcontratación offshore por parte de las organizaciones ha venido consolidándose gracias a los avances en las tecnologías de la información y a las diferencias en costos que esta conlleva. No obstante, una revisión de literatura sobre el fenómeno señala que los estudiosos del tema han centrado su atención en las empresas multinacionales de los sectores de manufacturas y de servicios, dejando de lado a las pequeñas y medianas empresas (RYME). A través de la formulación de una serie de proposiciones, este documento sugiere que las PYME, debido a sus características y necesidades particulares, también podrían obtener beneficios de este modelo de tercerización. El documento discute además las similitudes y diferencias en las motivaciones de PYME y empresas multinacionales para subcontratar actividades más allá de sus fronteras. Esta información resulta ser importante para que proveedores en el extranjero puedan adaptar y ampliar su oferta con base en las necesidades de estas empresas.

PALABRAS CLAVE:

tercerización en el extranjero, motivaciones, PYMES, empresas multinacionales.RESUMO:

A subcontratação offshore por parte das organizações tem se consolidado, graças às diferenças em custos que isso implica e aos avanços na tecnologia da informação. Porém, uma revisão de literatura sobre o fenômeno sinaliza que os estudiosos do tema centraram sua atenção nas empresas multinacionais dos setores de manufaturas e de serviços, sem considerar pequenas e médias empresas (PME). Através da formulação de uma série de proposições, este documento sugere que as pme, devido a suas características e necessidades particulares, também poderiam obter beneficios deste modelo de terceirização. O documento também discute as similaridades e diferenças nas motivações de PME e empresas multinacionais para subcontratar atividades além das suas fronteiras. Essa informação resulta ser importante para que fornecedores no exterior possam adaptar e ampliar a sua oferta com base nas necessidades dessas empresas.

Clasificación JEL F23, F29, M16.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE:

terceirização no exterior, motivações, PME, empresas multinacionais.RESUME:

L'outsourcing offshore de la part des organisations s'est consolidé grâce aux progrès des technologies de l'information et aux différences de coûts impliquées. Cependant, une revue de la littérature sur le phénomène indique que les chercheurs du sujet ont concentré leur attention sur les entreprises multinationales dans les secteurs de la fabrication et des services, laissant de côté les petites et moyennes entreprises (PME). En partant de la formulation d'une série de propositions, ce document suggère que les PME, en raison de leurs caractéristiques et de leurs besoins particuliers, pourraient également bénéficier de ce modèle d'externalisation. Le document discute également des similitudes et des différences dans les motivations des PME et des sociétés multinationales à externaliser des activités au-delà de leurs frontières. Cette information est importante pour les fournisseurs à l'étranger voulant adapter et élargir leur offre en fonction des besoins de ces entreprises.

Clasificación JEL F23, F29, M16.

MOTS-CLE:

externalisation à l'étranger, motivations, PME, multinationales.Introduction

Offshore outsourcing has been experiencing accelerated growth in practice (Doh, 2005). However, there is a fragmentation of existing research that has prevented the accumulation of knowledge on the subject (Mihalache & Mihalache, 2015). A review of published material shows that the few researchers who have put time and effort into the study of offshore outsourcing have focused on theoretical issues and/or activities of multinational enterprises (MNEs) within the manufacturing and services sectors, leaving behind small and medium enterprises (SMEs). It is the purpose of this paper to address this issue, concentrating its discussion on the benefits of offshore outsourcing for SMEs versus MNEs.

Sourcing strategy is defined in the literature as the decisions that determine the supply of components for production and the markets to be served (Davidson, 1982; Kotabe, 1990; Kotabe & Omura, 1989; Kotabe & Swan, 1994). Kotabe (1998) develops a matrix that shows four different types of sourcing strategies that a firm could consider depending on its location and whether they are making or buying. The four strategies are: domestic in-house sourcing, offshore subsidiary sourcing, domestic purchase arrangement (domestic outsourcing) and offshore outsourcing.

Di Gregorio, Musteen and Thomas (2009) define offshore outsourcing as those activities that an organization subcontracts in a foreign country, including both manufacture and services. This practice has been associated with overall economic benefit in terms of productivity, quality and customer satisfaction (Farrell, 2003; Tate & Ellram, 2009). Furthermore, highly competitive markets resulting from globalization are pushing firms to subcontract activities overseas in order to stay in business. Offshore outsourcing started as a regional practice in the 1960s, but economic liberalization and improvements in the telecommunications sector have made it possible to transfer business functions to other firms located around the world (Agrawal, Goswami & Chatterjee, 2010; Bahrami, 2009).

Alternatively, there has been some debate regarding the downward implications of offshore outsourcing such as the loss of jobs (Drezner 2004; Tate & Ellram, 2009) by clearing out the productive base from homeland (James, 2011). Additionally, Mihalache and Mihalache (2015) indicate there are two main types of risks associated with this practice. The first one is the strategic risk, which refers to the diminishing control over some of the firm's capabilities. The second is the operational risk, which refers to the costs of doing business abroad (i.e. wage levels, currency fluctuations, cultural barriers).

The subcontracting of manufacturing activities internationally is widely known, but recently services offshore outsourcing has been a growing phenomenon (Musteen & Ahsan, 2011; Tate, Ellram, Bals & Hartmann, 2009). Some scholars have even started to pay attention to the offshore outsourcing of subareas within the services sector such as professional services (Di Gregorio et al., 2009; Ellram, Tate & Billington, 2008; Sinha, Akoorie, Ding & Wu, 2011), opening doors for future research endeavors.

Most of the studies related to offshore outsourcing have been in the context of MNES, rarely addressing this topic from the perspective of SMEs (Di Gregorio et al., 2009; Doh, 2005; Kotabe, 1992; Scully & Fawcett, 1994; Sinha et al., 2011; Yu & Lindsay, 2011). The fact that global outsourcing of manufacturing tasks by MNEs is considered a more mature business practice (Orberg & Pedersen, 2012) could be a possible explanation. Among scholars, Hätönen and Eriksson (2009) stand out with their work centered on the evolution of the concept. Bierce (2003) also develops a typology of the different ways that offshore outsourcing can take place. Additionally, Bertrand (2011) addresses the impact of this practice on the export performance of MNEs.

Perhaps, another reason for the lack of studies focused on SMEs is that researchers typically see these firms as basically serving domestic markets and/or users of locally available resources, although scholars recognize that SMEs are actively engaged in the international arena (Mohiuddin, 2011; Sen & Haq, 2010; Yu & Lindsay, 2011). For example, Bell (1995), Craig and Douglas (1996), and Liesch and Knight (1999) state the importance of these firms for their local economies in terms of export growth and employment. In 2002, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) mentions that "SMEs account for between a quarter and two-fifths of worldwide manufactured exports" (George, Wiklund & Zahra, 2005, p. 210).

In the line of analyzing sourcing strategies, Hätönen and Eriksson (2009) created a literature analysis framework based on the research and practice of outsourcing of MNEs since the decade of the 1980s. Their analysis, guided by the why, how, what, where, and when firms outsource, led them to capture the evolution of the concept in three distinct eras: Big Bang, when it gained popularity; the Bandwagon, when companies started to follow the trend; and Barrierless Organization, when boundaries became blurry and faded. As part of the growth of outsourcing, different theoretical approaches emerge in each era, giving insights about the possible answers for the five basic questions concerning the topic.

Using the theoretical framework of Hätönen and Eriksson (2009), the purpose of this paper is to question if SMEs could also benefit from offshore outsourcing given their particular characteristics, and to inquire about the possible tangencies and differences in the motivations that these firms might have to subcontract internationally in comparison to manufacturing MNEs. Knowing what drives SMEs to engage in offshore outsourcing is especially important for the countries and the foreign suppliers in order to adapt and expand their offerings to the particular needs of these firms. Propositions will be established in an attempt to model the possible motivations for this business practice.

Profiling the Firms

Multinational Enterprises

A multinational enterprise is a firm that engages in foreign direct investment (FDI) and owns or -in some way- controls value-added activities in more than one country (Dunning & Lundan, 2008). As these authors state, the latter is accomplished by engaging in a variety of cross-border cooperative ventures such as licensing agreements, turnkey operations and strategic alliances.

A distinctive feature of MNEs is that besides exchanging goods and services across national boundaries, goods and services are transacted internally before or after carrying out a value-added activity owned or controlled in a foreign country (Dunning & Lundan, 2008). According to these authors, this means that MNEs access, organize and coordinate multiple value-added activities across national boundaries, making them the only institutions that engage in both cross-border production and transactions.

A typical multinational firm possesses some degree of market power due to the intangible assets it owns, such as advanced technology, brand name and marketing skills (Fujita, 1995). Furthermore, MNEs usually have an independent department for research and development (R&D) in their home country; and, its internationalization is growing because of the increasing importance of economies of scope, shorter product cycles and access to better scientific and technical personnel (United Nations, 1992).

Overseas operations, including the foreign sourcing of intermediate goods and knowledge, have become the basis of global competitiveness for the world's leading industrial and services MNEs (Dunning & Lundan; Dunning & Mckaig-Berliner, cited in Dunning & Lundan, 2008). At the same time, MNEs are also increasingly participants in international networks of related economic activity and as their systems tend to increasingly concentrate on their core value-added activities, making these arrangements is becoming more important (Dunning & Lundan, 2008).

Small and Medium-sized Enterprises

"Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are non-subsidiary, independent firms which employ fewer than a given number of employees. This number varies across countries" (OECD, 2005, p. 17). Some scholars consider SMEs as specialists, suppliers of raw materials, components, parts, and subassemblies to MNEs, thereby becoming a key player in the global supply chain setup. SMEs are seen as narrower in vision, with shorter term goals than MNEs. Typically, SMEs deal with a highly centralized decision-making process, small capital base, limited information database, and low R&D emphasis, vis-à-vis MNEs (Morya & Dwivedi, 2009).

Besides the differences between SMEs and MNEs described by Morya and Dwivedi (2009), the literature on SMES highlights some of the characteristics of these firms that make their entry to foreign markets and the expansion of sales more difficult than that of MNEs. Internal lack of resources and skills seems to be a distinctive characteristic and the one most agreed upon by researchers (Chetty & Agndal, 2007; George et al., 2005; Kamyabi & Devi, 2011; Murphy et al., 2012; Oviatt & McDougall, 1994; Reuber & Fischer, 1997). Additionally, George et al. (2005) also include international inexperience as a particular feature of SMEs.

Emphasizing another distinctive feature of SMEs, Chetty and Holm (2000), Di Gregorio et al. (2009) and Korhonen, Luostarinen and Welch (1996), mention that some researchers, without focusing on the extent and scope of SMEs internationalization, have found some evidence indicating that the process of doing business outside the country of origin usually begins with the sourcing activity instead of the direct and indirect exports. Still, the small set-up makes it difficult for these firms to fully achieve economies of scale, which in turn causes an increase in overhead costs (Agrawal et al., 2010).

Additionally, Di Gregorio et al. (2009) point out that SMEs have a strong entrepreneurial perspective and an ability to adopt innovations that arise from their relations abroad. Others underline the ability of SMEs to adapt their structures and processes to the dynamic of overseas competition (Liesch & Knight, 1999). In this line, Etemad (2004) mentions that these firms are known for having a rapid pace, evidenced in the short life cycles of products and technology and the high cost of R&D.

Manufactures

Manufacturing has particular characteristics that distinguish it from other economic sectors. Lovelock and Wirtz (2016) mention that, typically, inputs and outputs needed for operational activities tend to be consistent, and that inventory is possible considering that goods can be stored. Additionally, according to these authors, manufacturing requires physical distribution channels, and clients are not involved in the production of the goods.

Somehow, all of the above characteristics make it possible to subcontract manufacturing activities in countries outside national borders. For example, when standardization of production is achieved, replication is feasible in other parts of the world. Similarly, one of the advantages of having inventory is that during the time span needed for goods to move from a location to the consumer, demand can be met with the product in storage. Moreover, production processes can be established in remote locations since clients are not directly involved in them. Finally, goods need to be moved from the manufacturing site to the buyer through physical channels, regardless of the location of the customer. For these reasons, the trend towards (offshore) outsourcing of manufacturing-related activities has been particularly pronounced (McIvor, 2010).

Services

Services firms usually carry out activities that can be classified into two types: the core service and the supplementary services (Kotabe & Murray, 2004; Lovelock & Wirtz, 2016). The core service includes those activities the company must provide and perform well to stay in business, while the supplementary services are those needed to carry out the core service or to improve its quality (Kotabe & Murray, 2004). The latter are probably more likely to be conducted offshore.

Tate and Ellram (2012) mention two aspects that differentiate services from goods: the nature of the relationships and how value is created. In this regard, academics have come up with a variety of characteristics to conceptualize this differentiation, particularly agreeing in four of them (Lovelock & Gummesson, 2004). The first characteristic is intangibility, meaning that services cannot be touched or grasped mentally, and this is considered a critical distinction. The second is heterogeneity, which refers to variability or difficulty in achieving uniform output. The third is inseparability, denoting a simultaneous production and consumption process. The fourth and last is perishability, which means that services cannot be saved, stored, resold or returned. Most of these characteristics represent a challenge for services firms in regards to performing particular activities overseas.

The degree of intangibility provides a way to classify services firms as "pure" or "non-pure", depending on the amount of tangible or intangible elements embedded in their activities (Shostack, 1977). Service-related activities with a higher degree of intangibility usually require the involvement of people (Kotabe & Murray, 2004; Lovelock & Yip, 1996) and tend to be more customized in order to fit the needs of particular customers (Bitner, Brown & Meuter, 2000; Kotabe & Murray, 2004). In contrast, services firms that engage in activities with a lower degree of intangibility typically make use of physical goods, which implies there is a gap between the order and the actual delivery of the good (Kotabe & Murray, 2004).

According to Lovelock (1983), a useful way to identify suitable strategies for services is to group them by their shared characteristics. In this context, the author presents a classification scheme that considers the nature of the service act, the relationship between the service firm and the customer, the customization and judgment in the service delivery, the nature of demand and supply, and the method of service delivery. This classification makes it possible to define which activities can be more easily outsourced abroad.

Offshore Outsourcing: The Motivations Underneath

Academics have combined different theoretical approaches to address the motivations of firms that seek subcontracting their activities, either domestically or overseas. Cost, resource and organizational perspectives have been the most reiterated explanations for outsourcing, particularly among MNEs. Some scholars (Di Gregorio et al, 2009; Sinha et al, 2011) argue that such explanations are equally valid for SMEs.

Researchers explain that firms' motives to engage in offshore outsourcing typically change over time (Nieto & Rodríguez, 2011; Lewin & Couto, 2007). Initially, firms pursue cost reductions and efficiency in other countries, but as the need for resources and flexibility arises (Nieto & Rodríguez, 2011), structural adaptations take place (Tate et al, 2009). The paragraphs that follow discuss in some detail the three theoretical perspectives in the context of offshore outsourcing, including both MNEs and SMEs, but additionally making a distinction between manufacturing and services firms.

Transaction and Production Costs Perspective

The roots of the transaction cost perspective can be found in Coase's (1937) argument about the firm. He states that all economic exchanges have a cost and businesses will continue to grow until the costs of undertaking an additional activity inside the firm are equal to doing the transaction in the market or to subcontract it to another firm. Later on, Williamson separates transaction costs from production costs; the former embodies all the costs related to the movement of the product from one partner to the other within the supply chain, while the latter refers to all the costs associated with the production of a good or service (as cited in Kotabe, Mol & Murray, 2009). Harland, Knight, Lamming and Walker (2005) argue that the make or buy decision is based on the most effective option in terms of costs.

The reduction of transaction costs is one of the reasons for the establishment of foreign subsidiaries (Yang, Wacker & Sheu, 2012), since it is more efficient for MNEs to maintain control of intangible assets when there are market failures (Buckley & Casson, 1976; Dunning, 1988; Kotabe & Swan, 1994; Rugman, 1985). In addition, Kotabe et al. (2009) state that the establishment of a subsidiary may reduce the transaction costs related to institutional, cultural and language barriers; although firms subcontracting activities abroad can benefit from lower production costs, considering that foreign suppliers typically produce more efficiently (Kotabe et al., 2009). Overall, (offshore) outsourcing is probably an attractive option when savings in production costs outweigh transaction costs (Farrell, 2005; Kang, Wu & Hong, 2009; Sinha et al, 2011).

Manufacturing firms, regardless their size, typically require a significant amount of labor. This cost can be reduced when the related activities are subcontracted overseas (Choi & Beladi, 2014; Paul & Wooster, 2010). The production of many services, however, cannot be separated from their consumption. This makes the offshore outsourcing of labor-related tasks less viable and more oriented toward the reduction of administrative costs (Paul & Wooster, 2010).

The increasing internationalization of R&D has made MNEs, both from the manufacturing and services sectors, benefit from a cost reduction in this activity. Meanwhile, manufacturing SMEs can reduce costs by achieving economies of scale through offshore outsourcing, while services SMEs can avoid initial set-up costs and its related fixed costs (e.g., office space and infrastructure). Technology has played an important role in the reduction of transaction costs by reducing information asymmetries, particularly benefiting services firms given that they are mainly dependent on information technology and telecommunications to be offered (Tate et al., 2009). The development and evolution of business services models, producing costs reductions, have also driven the rise of service offshoring (Lovelock & Wirtz, 2016). Altogether, reducing costs frees financial resources that can be invested in other profit-generating activities, such as new lines of production or R&D, employee training, or adding a new business venture (Bahrami, 2009).

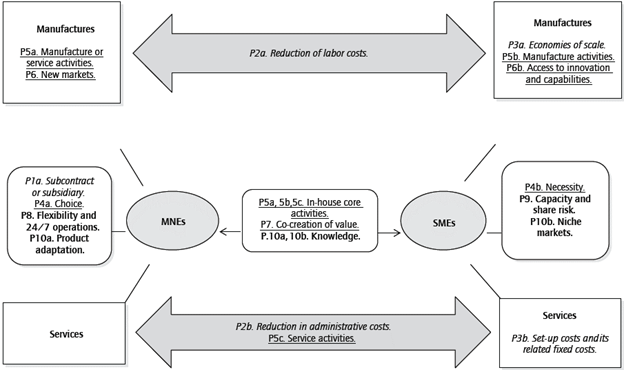

When it comes to the motivations of doing offshore outsourcing from the transaction and production costs perspective we propose the following:

P1a: MNES will subcontract activities overseas when the savings in production costs outweigh transaction costs.

P1b: MNES will establish a subsidiary when the transaction costs of doing business abroad outweigh the savings in production costs.

P2a: Manufacturing MNES and SMES mainly seek a reduction in labor costs.

P2b: Services MNES and SMES mainly seek a reduction in administrative costs.

P3a: Manufacturing SMES mainly seek economies of scale.

P3b: Services SMES mainly seek to avoid set-up costs and its related fixed costs.

Resource-based View Perspective

The perspective based on resources has surfaced with the objective of analyzing the sources of sustainable competitive advantage of firms. The resources of the firms (including capabilities) are strengths that allow enterprises to develop and implement strategies (Barney, 1991). These, in turn, facilitate companies to gain efficiency and effectiveness. Grant (1991) highlights that resources allow firms to obtain certain capabilities (core competences) that create competitive advantages.

Authors using the resource-based view (RBV) perspective have argued that firms decide to outsource as an opportunity to focus on their core competences (Gilley & Rasheed, 2000; Harland et al., 2005; Hätönen & Eriksson, 2009; Jain & Ramachandran, 2011). Therefore, focusing on these abilities allows the firm to center its attention in allocating resources on the activities it does best, and outsource those tasks for which it has a relative disadvantage (Gilley & Rasheed, 2000). This allows the exploitation of more advanced technology owned by other firms (Harland et al., 2005).

In the context of services, Kedia and Lahiri (2007) use the RBV perspective to explain strategic partnership as a way to gain from accumulative experience and learning scope resources. "RBV thus provides a compelling argument to empower the management of client companies to focus on their most promising activities by releasing them from non-core responsibilities" (Wirtz, Tuzovic & Ehret, 2015, p. 577). For Doh (2005), the motivation for focusing on the core competencies may have more weight than the motivation for merely reducing costs that has been taken from the transaction and production costs perspective. Value enhancement seems to be a more powerful motivation (Agrawal et al., 2010; Quinn, 1999).

Taking advantage of the resources available overseas is an important strategy for firms' international competitiveness (Bahrami, 2009; Kamyabi & Devi, 2011; McIvor, 2010; Orberg & Pedersen, 2012). MNEs have the option of establishing international subsidiaries, while SMEs depend on doing business with enterprises outside their home country. Smaller firms need this strategy to compensate their lack of certain capabilities and resources (Gooderham, Tobiassen, Doving & Nordhaug, 2004; Kamyabi & Devi, 2011). Nevertheless, as in the cost perspective, under the RBV there are also motivations for MNES to do offshore outsourcing.

Considering that core activities are those that offer competitive advantage, firms most likely will keep these under their control and subcontract abroad non-core activities. In the case of manufacturing multinationals, given their branding and marketing skills (Fujita, 1995), the activities that provide competitive advantage do not necessarily have to be manufacture-related. For example, firms like Nike specialize in the design and marketing phases while outsourcing abroad the manufacturing of their products. In contrast, the intangibility, inseparability and perishability of services makes it more common for these companies to gain competitive advantages from a service-related activity, even when other manufacturing or service activities are performed in-house or outsourced overseas (Kotabe & Murray, 2004). Business services such as call centers, financial processing, data management and accounting are some of the non-core activities being internationally outsourced by many firms because they lack the ability to provide competitive advantage (Tate & Ellram, 2012).

The heterogeneity of services increases their asset specificity, resulting in a smaller amount of the core business being subcontracted abroad. In the case of manufacturing firms, activities with high asset specificity remain difficult to imitate, and therefore more challenging to outsource; however, technology is making outsourcing possible over time (Kamyabi & Devi, 2011; Massini & Miozzo, 2012). As a result, the manufacturing industry is becoming saturated, making offshore outsourcing an attractive tool for multinationals to access new markets (Gilley & Rasheed, 2000). For manufacturing SMEs, decreasing transportation and communication costs are allowing access to sources of innovation and dynamic capabilities (Sinha et al., 2011).

Offshore outsourcing allows firms to take advantage of the existing experience around the world (Bean, 2003), where suppliers are specialized companies that offer higher quality and expertise in a particular area and, therefore, can contribute to the creation of knowledge (Agrawal et al., 2010; Quinn & Hilmer, 1994). Through this interaction between firm and supplier occurs a co-creation of value (Songailiene, Winklhofer & McKechnie, 2011).

Multinationals have the financial resources to take advantage of the worldwide capabilities available through the establishment of subsidiaries, whereas smaller firms do not have the same option. Consequently, we propose:

P4a: Offshore outsourcing is a matter of choice for MNEs.

P4b: Offshore outsourcing is necessary for the survival and acquisition of competences by SMEs.

Subcontracting overseas the non-core activities can provide certain benefits to all type of firms, although it is still important to perform core activities in-house, which provides competitive advantage. Therefore, we propose:

P5a: Manufacturing MNEs perform the core activities in-house, which can be manufacture-or-service-related.

P5b: Manufacturing SMEs perform the core activities in-house, which are manufacture-related.

P5c: Services firms perform the core activities in-house, which are service-related.

When it comes to manufacturing firms, the main motivation to search for international suppliers basically differs depending on the size. Smaller firms lack more resources than larger firms, but have an advantage in capturing niche markets. Thus, we propose:

P6a: Manufacturing MNEs seek new markets through offshore outsourcing.

P6b: Manufacturing SMEs seek access to sources of innovation and capabilities.

Nevertheless, all firms, regardless their size and industry, equally benefit from the expertise and knowledge of international suppliers. As a result, we propose:

P7: MNEs and SMEs from the manufacturing and services sectors seek co-creation of value by partnering with international suppliers.

Organizational Perspective

Within the broad range of theories about the organization and the firm, Hätönen and Eriksson (2009) point out that systems theory (Alexander, 1964; Simon, 1962) and network theory (Hakansson & Johanson, 1992; Johanson & Mattson, 1988) have been used in the literature to explain the motivations of MNEs to do outsourcing. The systems perspective sees the organization as interconnected subsystems that are mutually dependent (Alexander, 1964; Simon, 1962). In a complementary way, a network is composed of enterprises that act more like partners with common objectives rather than adversaries (Hunt, Arnett & Madhavaram, 2006).

Previous research has found that another motivation for MNEs (Hätönen & Eriksson, 2009) and manufacturing firms (Scherrer-Rathje, Deflorin & Anand, 2014) to outsource is the need to transform the organization into an adaptive system in an era where sustainable competitive advantage not necessarily lies in cost-efficiency or in the resources, but in the flexibility of the organization. Thus, systems theory offers a useful approach by focusing on the interrelated processes that can make the firm more adaptable, while the network approach offers a valuable way of understanding the complex relationships among the actors involved in each of the processes (Hätönen & Eriksson, 2009).

For all types of firms, finding a supplier they can trust and establish a long-term relationship facilitates the decision of doing offshore outsourcing (Agrawal et al, 2010). Establishing and managing a partnership is particularly easier for SMEs given their entrepreneurial skills and ease for doing business (Etemad, 2004). For MNEs, these relationships with foreign companies are important because they allow a degree of flexibility that vertically integrated organizations usually do not have (Agrawal et al., 2010). In addition, they enable business transformations that facilitate 24/7 operations (Bahrami, 2009; Bean, 2003). Finally, through these partners MNEs acquire knowledge about culture and consumption patterns in other countries (Bahrami, 2009) that facilitate product adaptation.

SMEs can equally benefit from gathering information about culture and consumption patterns, but their focus is directed towards finding niche markets. Additionally, these small companies can achieve increased operational capacity and reduction of risk (Mazzanti, Montresor & Pini, 2011; Rasheed & Gilley, 2005; Sinha et al, 2011); although MNEs can also gain from the latter, but to a lesser extent.

Following Agrawal et al. (2010), establishing long-term relationships with a trustful supplier is an important part in any firm's decision for offshore outsourcing. However, the benefits multinationals and smaller firms gain from these partnerships may differ. With this in mind, we propose the following:

P8: MNEs seek through partnerships with suppliers to increase flexibility and business transformations to operate 24/7.

P9: SMEs seek through partnerships with suppliers to increase capacity and share the risks.

P10: Both MNEs and SMEs seek through partnerships with suppliers to gain knowledge about foreign cultures and consumption patterns, although MNEs pursue information that is valuable for product adaptations, while SMES focus on finding niche markets.

Concluding Remarks

The practice of offshore outsourcing has shown accelerated growth, particularly by MNEs. However, a reduced number of academics have shown interest in the theoretical issues or topics of offshore outsourcing involving SMEs. Most probably, researchers perceive SMEs as being too involved with domestic markets, even when scholars themselves acknowledge that SMEs play important roles in the international arena (i.e. export and employment growth). Furthermore, economic liberalization and improvements in telecommunications have made possible to transfer business activities to firms located around the world, contributing to offshore outsourcing growth.

The purpose of this paper was to question if SMEs could also benefit from offshore outsourcing given their particular characteristics, and to inquire about the possible similarities and differences in the motivations these firms might have to subcontract internationally in comparison to MNEs. Knowing what drives SMEs to subcontract internationally is especially important for the countries and the foreign suppliers in order to adapt and expand their offerings to the particular needs of these firms. The propositions established in this paper are an attempt to model the possible motivations based on the existing literature (see appendix 1).

Our review of the available literature leads us to conclude that even when the motives to engage in offshore outsourcing may change over time, both MNEs and SMEs might participate in international outsourcing as a way of reducing labor costs. These costs are typically lower in underdeveloped and emerging economies, whereas in the developed world labor costs are increasing due to demands from unions and/or due to the cost of living in those countries. One could argue that as manufacturing evolves and new ways are introduced to automate production activities, MNEs will be motivated to base their offshore activities on market expansion and/or competitive advantages rather than on labor costs.

The literature also reveals that in the case of services organizations involvement in offshore outsourcing is probably due to the need to reduce administrative costs related to activities such as information processing, customer services and research and development, rather than to the service provision itself. This is not true on those occasions in which services providers cannot separate production from consumption, as would be the case of haircuts and surgeries, for example. However, as services providers look to satisfy customers' needs without simultaneously being present at the location of production (i.e. courses taught at a distance), offshore outsourcing to reduce production costs could become an attractive option.

Following the RBV, engaging in offshore outsourcing is advantageous when an organization needs to focus on core competencies and recognizes that it cannot improve as needed in a number of operational (productivity) and strategic (goal achievement) areas. That is the moment to search for answers wherever available. Although most firms equally face competition from domestic and international suppliers, SMEs probably lack more competencies than larger organizations; thus, are in more need to subcontract third parties outside their borders in order to succeed in places where they do business. MNEs will also need to subcontract offshore in order to advance market expansion and to get to new developments within their area of business (i.e. innovations). As the globalization of operations and markets continue to move forward, new competition will be available, and markets will be able to communicate with suppliers anywhere in the world. Stagnation is no longer acceptable, so partnerships and strategic alliances are becoming imperative for doing business.

In the case of SMEs, alliances and partnerships might be easier to implement. We assert this because these type of firms are known for being more flexible and easier to adapt than their counterparts (MNEs). Probably, it is because SMEs are characterized by fewer bureaucratic layers than MNES, because in many cases they are managed by its founder who defines the route to follow without delays. Increasing production and marketing capabilities might be more of a motivation for SMEs to engage in partnerships, either because market saturation makes sales growth difficult or because there are no local suppliers to look at as investors.

Nonetheless, MNEs could also benefit from finding trusted partners outside their domestic frontiers who can help them achieve more flexibility, which nowadays seems be a more important business endeavor for these firms.

The conceptual framework and the typology suggest an opportunity for theory building, empirical testing, development of better measures and methods, and the application/replication of findings from other fields. Following, Mihalache and Mihalache (2015), future research should consider a more integrated approach. The propositions in this study provide various starting points for research. Each one could be explored and expanded through empirical research. In addition to the basic research suggested by the framework and propositions, there is a need for research that will illuminate the differential importance and differential effects across types of MNEs and SMEs. Research opportunities also are available in exploring the ability to achieve particular objectives of the firm, and at what cost.

Our research has limitations as well. We centered our attention on the motivations for offshore outsourcing, yet there are risks involved that were not fully considered. Although the propositions are based on the literature available at the time of writing this paper, they have not been empirically tested. In addition, we did not consider the place of origin of the firms. Perhaps, the motivations for subcontracting internationally would be different if a distinction was to be made between firms from advanced and emerging economies. Furthermore, studies such as that by Musteen and Ahsan (2013) introduce an analysis from the intellectual capital perspective that goes beyond the theories usually cited in the literature on offshore outsourcing. Future research should take into account new theories and keep in mind that prominent MNEs in the manufacturing sector, such as Apple, Ford and General Electric, are reshoring their manufacturing activities back to their homeland (Abbasi, 2016).

References

Appendix 1. Summary of the motivations of firms for offshore outsourcing based on the interactions between the theoretical perspectives and each type of firm.

Manufactures

Note. Transaction and Production Costs Perspective (italics); Resource-based View Perspective (underline); Organizational perspective (bold). Source: Authors' creation based on the literature review.

Referencias

Abbasi, H. (2016). It's not offshoring or reshoring but right-shoring that matters. Journal of Textile and Apparel, Technology and Management, 10(2), 1-6.

Agrawal, S., Goswami, K., & Chatterjee, B. (2010). The evolution of offshore outsourcing in India. Global Business Review, 11(2), 239-256. doi: 10.1177/097215091001100208.

Alexander, C. (1964). Note on the synthesis of form. Boston, MA, USA: Harvard University Press.

Bahrami, B. (2009). A look at outsourcing offshore. Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal, 19(3), 212-223. doi: 10.1108/10595420910962089.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99-120.

Bean, L. (2003). The profits and perils of international outsourcing. The Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance, 14(6), 3-10.

Bell, J. (1995). The internationalization of small computer software firms. European Journal of Marketing, 29(8), 60-75.

Bertrand, O. (2011). What goes around comes around: Effects of offshore outsourcing on the export performance of firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(2), 334-344. doi: 10.1057/jibs.2010.26.

Bierce, W. B. (2003). International outsourcing: The legal view of what's different. Retrieved from: http://www.outsourcing-law.com/articles/legalview.asp. [URL]

Bitner, M. J., Brown, S. W., & Meuter, M. L. (2000). Technology infusion in service encounters. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(1), 138-149.

Buckley, P. J., & Casson, M. (1976). The future of the multinational enterprise. London: Macmillan.

Chetty, S. K., & Agndal, H. (2007). Social capital and its influence on changes in internationalization mode among small and medium-sized enterprises. Journal of International Marketing, 15(1), 1-29. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1509/jimk.15.1.001. [URL]

Chetty, S. K., & Holm, D. B. (2000). Internationalization of small to medium-sized manufacturing firms: A network approach. International Business Review, 9(1), 77-93.

Choi, J. Y., & Beladi, H. (2014). Internal and external gains from international outsourcing. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 23(2), 299-314.

Coase, R. H. (1937). The nature of the firm. Economica, 4(16), 386-405.

Craig, C. S., & Douglas, S. P. (1996). Developing strategies for global markets: An evolutionary perspective. Columbia Journal of World Business, 31(Spring), 70-81.

Davidson, W. (1982). Global strategic management. New York, NY, USA: John Wiley & Sons.

Di Gregorio, D., Musteen, M., & Thomas, D. E. (2009). Offshore outsourcing as a source of international competitiveness for SMEs. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(6), 969-988. doi: 10.1057/jibs.2008.90.

Doh, J. P. (2005). Offshore outsourcing: Implications for international business and strategic management theory and practice. Journal of Management Studies, 42(3), 695-704. DOI:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2005.00515.x.

Drezner, D. W. (2004). The outsourcing bogeyman. Foreign Affairs, 83(3), 22-34.

Dunning, J. (1988). The eclectic paradigm of international production: A restatement and some possible extensions. Journal of International Business Studies, 19(1), 1-31.

Dunning, J., & Lundan, S. (2008). Multinational enterprises and the global economy (2nd Ed.). Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing Inc.

Ellram, L. M., Tate, W. L., & Billington, C. (2008). Offshore outsourcing of professional services: A transaction cost economics perspective. Journal of Operations Management, 26(2) 148-163.

Etemad, H. (2004). Internationalization of small and medium-sized enterprises: A grounded theoretical framework and an overview. Canadian Journal of Administrative Science, 21(1), 1-21.

Farrell, D. (2005). Offshoring: Value creation through economic change. Journal of Management Studies, 42(3), 675-683.

Fujita, M. (1995). Small and medium-sized transnational corporations: Salient features. Small Business Economics, 7(4), 251-271.

George, G., Wiklund, J., & Zahra, S. (2005). Ownership and the internationalization of small firms. Journal of Management, 31(2), 210-233. doi: 10.1177/0149206304271760.

Gilley, M., & Rasheed, A. (2000). Making more by doing less: An analysis of outsourcing and its effects on firm performance. Journal of Management, 26(4), 763-790.

Gooderham, P. N., Tobiassen, A., Doving, E., & Nordhaug, O. (2004). Accountants as sources of business advice for small firms. International Small Business Journal, 22(1), 5-22.

Grant, R. M. (1991). The resource-based theory of competitive advantage: Implications for strategy formulation. California Management Review, 33(3), 114-135.

Harland, C., Knight, L., Lamming, R., & Walker, H. (2005). Outsourcing: Assessing the risks and benefits for organizations, sectors and nations. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 25(9), 831-850.

Hakansson, H., & Johanson, J. (1992). A model of industrial networks. In: B. Axelsson & G. Easton (Eds.). Industrial networks: A new view of reality (pp. 28-34). London: Routledge.

Hätönen, J., & Eriksson, T. (2009). 30+ years of research and practice of outsourcing: Exploring the past and anticipating the future. Journal of International Management, 15, 142-155. doi:10.1016/j.intman.2008.07.002.

Hunt, S. D., Arnett, D. B., & Madhavaram, S. (2006). The explanatory foundations of relationship marketing theory. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 21(2), 72-87. doi: 10.1108/10610420610651296.

Jain, R. K., & Ramachandran, N. (2011). Factors influencing the outsourcing decisions: A study of the banking sector in India. Strategic Outsourcing: An International Journal, 4(3), 294-322. doi: 10.1108/17538291111185485.

James, G. (2011). Top ten reasons offshoring is bad for business. CBS Mo-neywatch. Accessed December 15, 2016 from: http://www.cbsnews.com/news/top-10-reasons-offshoring-is-bad-for-business. [URL]

Johanson, J., & Mattson, L. G. (1988). Internationalization in industrial systems: A network approach. In: N. Hood & J. E. Vahlne (Eds.). Strategies in global competition (pp. 287-314). London: Routledge .

Kamyabi, Y., & Devi, S. (2011). An empirical investigation of accounting outsourcing in Iranian SMES: Transaction cost economics and resource-based views. International Journal of Business and Management, 6(3), 81-94.

Kang, M., Wu, X., & Hong, P. (2009). Strategic outsourcing practices of multinational corporations (MNCS) in China. Strategic Outsourcing: An International Journal, 2(3), 240-256.

Kedia, B. L., & Lahiri, S. (2007). International outsourcing of services: A partnership model. Journal of International Management, 13(1), 22-37. doi: 10.1016/j.intman.2006.09.006.

Korhonen, H., Luostarinen, R., & Welch, L. (1996). Internationalization of SMEs: Inward-outward patterns and government policy. Management International Review, 36(4), 315-329.

Kotabe, M. (1990). The relationship between offshore sourcing and in-novativeness of U.S. multinational firms: An empirical investigation. Journal of International Business Studies, 21(4), 623-638.

Kotabe, M. (Ed.). (1992). Global sourcing strategy: R&D, manufacturing, and marketing interfaces. Praeger Pub Text.

Kotabe, M. (1998). Efficiency vs. effectiveness orientation of global sourcing strategy: A comparison of U.S. and Japanese multinational companies. The Academy of Management Executive, 12 (4), 107-119. doi: 10.5465/AME.1998.1334000.

Kotabe, M., Mol, M., & Murray, J. (2009). Global sourcing strategy. In: M. Kotabe & K. Helsen (Eds.). The SPCE handbook of international marketing (pp. 288-303). London: SAGE publications. doi: 10.4135/9780857021007.n14.

Kotabe, M., & Murray, J. (2004). Global procurement of service activities by service firms. International Marketing Review, 21(6), 615-633. doi: 10.1108/02651330410568042.

Kotabe, M., & Omura, G. S. (1989). Sourcing strategies of European and Japanese multinationals: A comparison. Journal of International Business Studies, 20(1), 113-130.

Kotabe, M., & Swan, K. S. (1994). Offshore sourcing: Reaction, maturation, and consolidation of U.S. multinationals. Journal of International Business Studies, 25(1), 115-140.

Lewin, A. Y., & Couto, V. (2007). Next Generation Offshoring: The Globalization of Innovation. Durham: Duke University CIBER/BOOZ Allen Hamilton Report.

Liesch, P. W., & Knight, G. A. (1999). Information internalization and hurdle rates in small and medium enterprise internationalization. Journal of International Business Studies, 30(2), 383-394.

Lovelock, C. (1983). Classifying services to gain strategic marketing insights. Journal of Marketing, 47(3), 9-20.

Lovelock, C., & Gummesson, E. (2004). Whiter services marketing? In search of a new paradigm and fresh perspectives. Journal of Service Research, 7(1), 20-41. doi: 10.1177/1094670504266131.

Lovelock, C., & Wirtz, J. (2016). Services marketing: People, technology, strategy (8th Ed.). New Jersey, NJ, USA: World Scientific Publishing.

Lovelock, C., & Yip, G. (1996). Developing global strategies for service business. California Management Review, 38(2), 64-86.

Massini, S., & Miozzo, M. (2012). Outsourcing and offshoring of business services: Challenges to theory, management and geography of innovation. Regional Studies, 46(9), 1219-1242.

Mazzanti, M., Montresor, S., & Pini, P. (2011). Outsourcing, delocalization and firm organization: Transaction costs versus industrial relations in a local production system of Emilia Romagna. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 23(7-8), 419-447.

McIvor, R. (2010). The influence of capability considerations on the outsourcing decision: The case of a manufacturing company. International Journal of Production Research, 48(17), 5031-5052.

Mihalache, M., & Mihalache, O. R. (2015). A decisional framework of offshoring: Integrating Insights from 25 years of research to provide direction for future. Decision Sciences, 47(6), 1103-1149. doi: 10.1111/deci.12206.

Mohiuddin, M. (2011). Research on offshore outsourcing: A systematic literature review. Journal of International Business Research, 10(1), 59-76.

Morya, K. K., & Dwivedi, H. (2009). Aligning Interest of SMEs with a Focal Firm (MNC) in a Global Supply Chain Setup. ICFAI Journal of Supply Chain Management , March, 49-59.

Murphy, P., Wu, Z., Welsch, H., Heiser, D., Young, S., & Jiang, B. (2012). Small firm entrepreneurial outsourcing: Traditional problems, non-traditional solutions. Strategic Outsourcing: An International Journal, 5(3), 248-275. doi: 10.1108/17538291211291774.

Musteen, M., & Ahsan, M. (2013). Beyond cost: The role of intellectual capital in offshoring and innovation in young firms. Entrepreneur-ship Theory and Practice, 37(2), 421-434.

Nieto, M., & Rodriguez, A. (2011). Offshoring of R&D: Looking abroad to improve innovation performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 42, 345-361.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]. (2002). Small and Medium Enterprise Outlook. Paris: OECD.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD] (2005). OECD SME and entrepreneurship outlook: 2005. Paris: OECD.

Orberg, P., & Pedersen, T. (2012). Offshoring and international competitiveness: Antecedents of offshoring advanced tasks. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40, 313-328. doi: 10.1007/s11747-011-0286-x.

Oviatt, B. M., & McDougall, P. P. (1994). Toward a theory of international new ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 25(1), 45-64.

Paul, D. L., & Wooster, R. B. (2010). An empirical analysis of motives for offshore outsourcing by US firms. The International Trade Journal, 24(3), 298-320.

Quinn, J. B. (1999). Strategic outsourcing: Leveraging knowledge capabilities. Sloan Management Review, 35(4), 43-55.

Quinn, J. B., & Hilmer, F. G. (1994). Strategic outsourcing. Sloan Management Review, 35(4), 43-55.

Rasheed, A. A., & Gilley, M. K. (2005). Outsourcing: National and firm-level implications. Thunderbird International Business Review, 47(5), 513-528.

Reuber, A. R., & Fischer, E. (1997). The influence of the management team's international experience on the internationalization behaviors of SMEs. Journal of International Business Studies, 28(4), 807-825.

Rugman, A. (1985). Internalization is still a general theory of foreign direct investment. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 121, 570-575.

Scherrer-Rathje, M., Deflorin, P., & Anand, G. (2014). Manufacturing flexibility through outsourcing: Effects of contingencies. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 34(9), 1242-1210. doi: 10.1108/IJOPM-01-2012-0033.

Scully, J. I., & Fawcett, S. E. (1994). International procurement strategies: Challenges and opportunities for the small firm. Production and Inventory Management Journal, 35(2), 39.

Sen, A., & Haq, K. (2010). Internationalization of SMEs: Opportunities and limitations in the age of globalization. International Business & Economics Research Journal, 9(5), 135-142.

Shostack, G. L. (1977). Breaking free from product marketing. Journal of Marketing, 41(2), 73-80.

Simon, H. (1962). The architecture of complexity. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 106, 467-482.

Sinha, P., Akoorie, M., Ding, Q., & Wu, Q. (2011). What motivates manufacturing SMEs to outsource offshore in China? Strategic Outsourcing: An International Journal, 4(1), 67-88. doi: 10.1108/17538291111108435.

Songailiene, E., Winklhofer, H., & McKechnie, S. (2011). A conceptualization of supplier-perceived value. European Journal of Marketing, 45(3), 383-418. doi: 10.1108/03090561111107249.

Fate, W., & Ellram, L. (2009). Offshore outsourcing: a managerial framework. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 24(3/4), 256-268. doi: 10.1108/08858620910939804.

Tate, W., & Ellram, L. (2012). Service supply management structure in offshore outsourcing. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 48(44), 8-29.

Tate, W., Ellram, L., Bals, L., & Hartmann, E. (2009). Offshore outsourcing of services: An evolutionary perspective. International Journal of Production Economics, 120(2), 512-524. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2009.04.005.

United Nations, Transnational Corporations and Management Division (1992). World Investment Report 1992: Transnational Corporations as Engines of Growth. New York, NY, USA: United Nations.

Yang, C., Wacker, J. G., & Sheu, C. (2012). What makes outsourcing effective? A transaction-cost economics analysis. International Journal of Production Research, 50(16), 4462-4476.

Yu, Y., & Lindsay, V. (2011). Operational effects and firms' responses: Perspectives of New Zealand apparel firms on international outsourcing. Logistics Management, 22(3), 306-323. doi: 10.1108/09574091111181345.

Wirtz, J., Tuzonic, S., & Ehret, M. (2015). Global business services: Increasing specialization and integration of the world economy as drivers of economic growth. Journal of Service Management, 26(4), 565-587.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Licencia

Derechos de autor 2018 Innovar

Esta obra está bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 3.0.

Todos los artículos publicados por Innovar se encuentran disponibles globalmente con acceso abierto y licenciados bajo los términos de Creative Commons Atribución-No_Comercial-Sin_Derivadas 4.0 Internacional (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).

Una vez seleccionados los artículos para un número, y antes de iniciar la etapa de cuidado y producción editorial, los autores deben firmar una cesión de derechos patrimoniales de su obra. Innovar se ciñe a las normas colombianas en materia de derechos de autor.

El material de esta revista puede ser reproducido o citado con carácter académico, citando la fuente.

Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons: