Analysing a method for small and medium sized companies to rate oil quality during immersion frying

Método de análisis de calidad del aceite durante el freído por inmersión para pequeñas y medianas empresas

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/ing.investig.v31n1.20566Keywords:

immersed frying, viscosity, Lovibond colour, anisidine value, oil deterioration. (en)freído por inmersión, viscosidad, color Lovibond, índice de anisidina, deterioro del aceite. (es)

Downloads

This work studied the deterioration of commercial Frytol oil in controlled frying conditions using the anisidine index (AI) as standard evaluation method. The effect of temperature and time was studied at 170°C for up to 10 hours and at 200°C for up to 6 hours in the presence of factors which speeded up oil deterioration: 1% and 8% water based on the mass of oil and non-lipid material, 1% and 6% based on the mass of oil. Air flow rate was kept constant at 25 L h-1. The relationship between AI, colour and viscosity was studied to evaluate the technical viability of measuring these variables as a function of time to be used as a method for rating oil deterioration by small and medium sized enterprises (SME). Oil deterioration was higher and faster at maximum study interval values for each experimental factor, although only the effect of temperature was significant (p<0.05). Red and yellow on the Lovibond scale were weakly related (AI R2=0.558 and R2=0.526, respectively), colour depending on frying temperature. Viscosity measured at 30°C had the highest coefficient of determination (R2=0.809) and was independent of frying temperature. Viscosity is thus a variable which can be used for determining frying oil deterioration in SME as a consequence of a significant change from 10 cP to 45 cP which is closer to frying oil deterioration limit (AI 156). It can facilitate determination and lower associated costs, there-by improving product quality and customer confidence in them.

Este trabajo estudió el deterioro de un aceite comercial, Frytollíquido, bajo condiciones controladas de freído, empleando como método estandarizado para su evaluación el índice de anisidina (IAn). Se determinó el efecto de la temperatura y del tiempo de fritura, 170 °C hasta 10 horas y 200 °C hasta 6 horas, en presencia de los acelera-dores: agua, 1% y 8% en peso con respecto al aceite, y material no lipídico, 1% y 6% en peso con respecto al aceite, manteniendo constante el flujo de aire en 25 L h-1. Posteriormente se estableció la relación del IAn con las propiedades color y viscosidad, para determinar su viabilidad técnica como métodos de valoración del deterioro de los aceites de fritura en pequeñas y medianas empresas (pyme). El aceite se deterioró más y en menor tiempo en los valores máximos del intervalo de estudio para cada uno de los factores experimentales, aunque sólo la temperatura tuvo un efecto estadísticamente diferente de cero (p <0,05), en el intervalo de estudio. Los colores rojo y amarillo en escala Lovibond tuvieron una relación débil con el Ian, R2 = 0,558 y R2 = 0,526 respectivamente, existiendo dependencia del color con la temperatura de freído. La viscosidad, medida a 30 °C, tuvo la mayor correlación (R2 = 0,809) y fue independiente de la temperatura de freído, de tal forma que puede emplearse para determinar el deterioro de los aceites de fritura en pyme. Un cambio radical en el valor de la viscosidad, de 10 cP a 45 cP en las cercanías del límite de deterioro de los aceites de fritura (IAn 156), la facilidad de su determinación y los bajos costos asociados, permitirá que este tipo de empresas puedan implementarla como variable de seguimiento, lo que mejorará la calidad de los productos y la confianza de los clientes en ellos.

Método de análisis de calidad del aceite durante el freído por inmer-sión para pequeñas y medianas empresas

Analysing a method for small and medium sized companies to rate oil quality during immersion frying Efraín Hisnardo Rojas Uribe1 , Paulo César Narváez Rincón2 1 Ingeniero Químico y Especialista en Ciencia y Tecnología de Alimentos, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá. ehrojasu@unal.edu.co 2 M.Sc Ingeniería, Ph.D. Ing.eniería, Profesor Asociado, Departamento de Ingeniería Química y Ambiental, Grupo de Procesos Químicos y Bioquímicos, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá. pcnarvaezr@unal.edu.co RESUMEN Este trabajo estudió el deterioro de un aceite comercial, Frytollíquido, bajo condiciones controladas de freído, empleando como método estandarizado para su evaluación el índice de anisidina (IAn). Se determinó el efecto de la temperatura y del tiempo de fritura, 170 °C hasta 10 ho-ras y 200 °C hasta 6 horas, en presencia de los acelera-dores: agua, 1% y 8% en peso con respecto al aceite, y material no lipídico, 1% y 6% en peso con respecto al aceite, manteniendo constante el flujo de aire en 25 L h-1. Posteriormente se estableció la relación del IAn con las propiedades color y viscosidad, para determinar su viabili-dad téc-nica como métodos de valoración del deterioro de los aceites de fritura en pequeñas y medianas empresas (pyme). El aceite se deterioró más y en menor tiempo en los valores máximos del intervalo de estudio para cada uno de los factores experimentales, aunque sólo la tempe-ratura tuvo un efecto estadísticamente diferente de cero (p <0,05), en el intervalo de estudio. Los colores rojo y amarillo en escala Lovibond tuvieron una relación débil con el Ian, R2 = 0,558 y R2 = 0,526 respectivamente, existiendo dependencia del color con la temperatura de freído. La viscosidad, medida a 30 °C, tuvo la mayor co-rrelación (R2 = 0,809) y fue independiente de la tempera-tura de freído, de tal forma que puede emplearse para determinar el deterioro de los aceites de fritura en pyme. Un cambio radical en el valor de la viscosidad, de 10 cP a 45 cP en las cercanías del límite de deterioro de los aceites de fritura (IAn 156), la facilidad de su determinación y los bajos costos asociados, permitirá que este tipo de empresas puedan implementarla como variable de seguimiento, lo que mejorará la calidad de los productos y la confianza de los clientes en ellos. Palabras claves: freído por inmersión, viscosidad, color Lovibond, índice de anisidina, deterioro del aceite. ABSTRACT This work studied the deterioration of commercial Frytol oil in controlled frying conditions using the anisidine index (AI) as standard evaluation method. The effect of temperature and time was studied at 170°C for up to 10 hours and at 200°C for up to 6 hours in the presence of factors which speeded up oil deterioration: 1% and 8% water based on the mass of oil and non-lipid material, 1% and 6% based on the mass of oil. Air flow rate was kept constant at 25 L h-1. The relationship between AI, colour and viscosity was studied to evaluate the technical viability of measuring these variables as a function of time to be used as a method for rating oil deterioration by small and me-dium sized enterprises (SME). Oil deterioration was higher and faster at maximum study interval values for each experimental factor, although only the effect of temperature was significant (p<0.05). Red and yellow on the Lovibond scale were weakly related (AI R2=0.558 and R2=0.526, respectively), colour depending on frying temperature. Viscosity measured at 30°C had the highest coefficient of determination (R2=0.809) and was independent of frying temperature. Viscosity is thus a variable which can be used for determining frying oil deterioration in SME as a conse-quence of a significant change from 10 cP to 45 cP which is closer to frying oil deterioration limit (AI 156). It can facilitate determination and lower associated costs, there-by improving product quality and customer confidence in them. Keywords: immersed frying, viscosity, Lovibond colour, anisidine value, oil deterioration. Recibido: octubre 05 de 2009. Aceptado: diciembre 31 de 2010 Introducción La fritura es un método de preparación de alimentos que consiste en introducir un alimento en aceite o grasa caliente, durante un período determinado, generalmente en presencia de aire, donde el aceite actúa como medio para la transferencia de calor y de masa, produciendo un calentamiento rápido y uniforme del producto (Navas, 2005; Yagüe, 2003), confiriéndole crocancia, sabor y color únicos, muy deseados por los consumidores (Gupta, 2004; Choe, 2007). Estas características son consecuencia, principalmente, de diferentes reacciones en el aceite de freído y en el propio alimento, generadas por compuestos de oxidación lipídica y productos de la reacción de Maillard, entre otros (Navas, 2005). Durante el freído por inmersión el alimento se cocina por transferencia de calor directa del aceite caliente hacia el alimento frío; cuando el alimento se adiciona al aceite caliente la temperatura del aceite desciende, la humedad superficial del alimento forma vapor rápidamente, mientras que el agua en el interior de él se difunde hacia la superficie, para finalmente pasar a la fase de vapor y viajar a través del aceite de freído hacia el aire atmosférico, lo que se evidencia por la presencia de burbujas en el seno del aceite. Cuanto más avanza el freído, el alimento comienza a obtener su color característico. El aceite se adsorbe en el alimento, generando una textura crujiente y un sabor característico (Gupta, 2004). Factores como elevadas temperaturas, presencia de oxígeno y agua en el aceite, promueven cambios físicos irreversibles, como incrementos en la viscosidad, el color y el espumado, disminución del punto de humo y reacciones químicas, entre ellas oxidación, hidrólisis y polimerización, factores que implican el deterioro (O´Brien, 2004; Saguy y Dana, 2003; Dobarganes, 2002; Sontag, 1982), y a niveles considerables podrían tener efectos negativos sobre la salud humana, ya que los compuestos producto de las reacciones pueden actuar como inhibidores enzimáticos, destructores de vitaminas, irritantes gastrointestinales o mutágenos potenciales (Clark y Serbia, 1991; Zakrzewski,1991; Keuneke, 1999). Para determinar el deterioro de un aceite, diversas investigaciones reportan la medición del índice de peróxido, índice de acidez, contenido de material no polar, el IAn, contenido de polímeros, índice de iodo, índice de ácido tiobarbitúrico, contenido de dienos conjugados, entre otros (Pokorny et al., 2001; Navas, 2005; Gupta, 2004; Rosell, 2001; Shahidi, 2005), de los cuales los más usados por su confiabilidad y relación con el deterioro son el material no polar y el IAn, con el inconveniente de la dificultad para su implementación en pyme por los equipos necesarios, la capacidad técnica requerida por las personas que deben realizar los análisis y los costos asociados (Benedito et al., 2007). El IAn mide la cantidad de aldehídos α y β insaturados en el aceite, así como la oxidación secundaria o la historia del aceite (O´Brien, 2004). Para proteger a los consumidores del riesgo de consumo de alimentos freídos con aceites deteriorados en varios países se han establecido regulaciones, donde el límite para establecer que el aceite no puede emplearse en la producción de alimentos corresponde a un contenido de material polar del 25% (Firestone, 2004; Shahidi, 2005; Gertz, 2000; Sahin et al., 2008), que equivale a un IAn de 156 (Boatella et al., 2000). Actualmente no existen sistemas prácticos y objetivos para la evaluación del deterioro de aceites de fritura en las pyme, ya que, por un lado, los métodos de determinación estandarizados que se utilizan para análisis de los aceites de fritura implican equipos y procedimientos de costos, tiempo y complejidad técnica que no están al alcance de estas empresas (Navas, 2005; Benedito, 2007), y por el otro, el uso de los sistemas de prueba rápida, que generalmente se utilizan en Europa y Estados Unidos, no se han generalizado en Latinoamérica, especialmente por el elevado costo de los equipos y su difícil consecución. Teniendo en cuenta lo anterior, este trabajo busca establecer un método práctico de determinación del límite de deterioro de los aceites de freído en las pyme, de tal forma que se facilite el monitoreo de la calidad del aceite de fritura en este tipo de empresas, lo que ayudará a la estandarización de los procesos y al mejoramiento de las características organolépticas para favorecer la calidad y confianza del consumidor en sus productos. C. I. Sigra S. A., empresa refinadora y productora de aceites de fritura, pretende, con el desarrollo de este trabajo, incrementar el valor agregado de su producto Frytollíquido, mediante la prestación de apoyo técnico a sus usuarios. Para ello se estudió el efecto de las variables temperatura, tiempo, humedad inicial y contenido de material no lipídico sobre el deterioro del aceite Frytollíquido, durante un proceso de freído controlado, a flujo de aire constante y midiendo el deterioro por medio del IAn. Luego se estableció la relación del IAn con las propiedades color y viscosidad, con el fin de determinar su viabilidad técnica como método de valoración del deterioro de los aceites de fritura en las pyme. La selección de estas dos variables se fundamentó en la relación que existe entre ellas y el deterioro (Gupta, 2005), y por la posibilidad de implementar procedimientos de fácil aplicación en las pyme, donde la medición consistiría en la comparación con unos patrones previamente definidos, como en el caso de las escalas Gardner de color y de viscosidad, empleadas en industrias como las de resinas, pinturas y recubrimientos. Este tipo de técnicas de caracterización reduce el costo de los equipos y del análisis, y el perfil técnico requerido por el personal a cargo es mínimo. Materiales y métodos Materiales. Se empleó una muestra de aceite fresco Frytollíquido, mezcla de aceite de soya y oleína de palma, elaborado por C. I. SIGRA S. A. (Bogotá), producto de la mezcla de 11 muestras tomadas de manera aleatoria. La muestra de aceite se caracterizó por acidez (AOCS Ca5a40 (09)), índice de peróxido (AOCS Cd853 (03)), punto de nube (AOCS Cc625 (09)), color Lovibond rojo y amarillo con celda de 5"¼ (AOCS Cc13e92 (09)) e IAn (NTC 4197, 2001). Los resultados promedio de la caracterización se muestran en la tabla 1, teniendo en cuenta que el valor de cada característica de cada muestra se midió por triplicado, de tal forma que el resultado corresponde al promedio de 33 datos. El material no lipídico se preparó a partir de 13 muestras obtenidas aleatoriamente de corteza de empanada cruda, provenientes de Empanadas de la Cima Ltda. (Bogotá), homogeneizadas por maceración y caracterizadas mediante el análisis proximal que presenta la tabla 2. Para la determinación del IAn se usó 4metoxianilina (p-Anisidina) y sulfato de sodio anhidro, provenientes de Merck (Darmstadt, Alemania) y 2,2,4-trimetil pentano proveniente de Mallinckrodt Baker Inc. (Phillipsburg, Estados Unidos). La panisidina se purificó siguiendo el procedimiento que se describe en la NTC 4197. Métodos. El IAn se midió de acuerdo al procedimiento descrito en la NTC 4197, utilizando un espectrofotómetro de luz visible Perkin Elmer modelo Lambda 3B (Perkin Elmer Inc., Massachusetts, Estados Unidos), con celda de 10 mm. Para medir el color Lovibond se siguió el procedimiento establecido en la AOCS Cc 13e92 (09), empleando un colorímetro Lovibond PFX 880 (The Tintometer Ltd, Wiltshire, Reino Unido) con celda 10 mm a una temperatura de 50 °C. La viscosidad se midió según el procedimiento descrito en la norma ASTM D2196, en un viscosímetro de rotación de cilindros concéntricos Brookfield modelo Visco 20 (Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, Reino Unido), utilizando una aguja RV/HA # 3 302S/S33, a una temperatura de 30 °C. Diseño de experimentos. Para la evaluación del deterioro del aceite a través del IAn se estudiaron las variables temperatura, presencia de material no lipídico, tiempo y humedad; se diseñó un experimento factorial multinivel para tres variables en dos niveles y una variable en tres niveles, así: material no lipídico, 1% y 6% en peso, humedad 1% y 8% en peso, ambas con respecto al aceite; temperatura de fritura, 170 y 200 °C, y tiempo, tomando muestras a las 6, 8 y 10 horas para los ensayos a 170 °C y a las 4, 5 y 6 horas para los de 200 °C. La razón de la diferencia en los tiempos de ensayo para cada temperatura es la influencia de esta variable sobre la velocidad de las reacciones de deterioro, lo cual hace que a 200 °C el aceite se deteriore más rápidamente que a 170 °C. El número total de ensayos del experimento es de 24, que se realizaron por duplicado. El proceso de fritura se desarrolló en forma controlada empleando un equipo Rancimat 679 (Metrohm AG, Suiza), manteniendo constante el flujo de aire al sistema en 25 L h1. Con la finalidad de evaluar la relación existente entre el IAn, la viscosidad y el color, se hicieron ensayos de deterioro a 170 °C por 9 horas y 200 °C por 6 horas, bajo condiciones de freído controladas en el equipo Rancimat 679 (Metrohm AG, Suiza), usando un 6% de material no lipídico, 8% de humedad y 25 L h1 de aire. El volumen de aceite utilizado en cada ensayo fue de 70 ml. Se tomaron muestras cada hora y los ensayos se efectuaron por duplicado. A cada muestra se le determinaron el IAn, la viscosidad dinámica y el color Lovibond. Los diseños de experimentos y el análisis de los resultados de ellos se analizaron estadísticamente con Statgraphics Centurión XV® versión 15.2.06 (Statpoint Inc. Virginia, Estados Unidos). Resultados y análisis Evaluación del deterioro del aceite a través del IAn. El análisis estadístico de los resultados del experimento que evaluó la influencia del tiempo, la temperatura, la humedad y el material no lipídico sobre el deterioro del aceite (Anova), mostró que solamente los efectos del tiempo y temperatura sobre el IAn son estadísticamente significativos, con el 95% de nivel de confianza (p <0,05), y que el incremento en el valor de estas variables aumenta significativamente el deterioro del aceite. Las figuras 1 y 2 muestran el efecto del tiempo y de la temperatura, y de la humedad inicial y el contenido de material no lipídico, respectivamente, sobre el IAn. En cada una de estas figuras se parametrizaron dos de las variables en el valor medio del intervalo de estudio, pero el comportamiento es cualitativamente semejante en todo el intervalo. En la figura 1 se observa que el incremento en la temperatura de fritura aumenta tanto el deterioro como la velocidad de él; este comportamiento confirma los reportes de Gupta (2004) y de Saguy (2003), donde afirman que si se controla esta variable se prolonga la vida útil del aceite. El deterioro se incrementa con la temperatura, porque hay la suficiente energía para romper los enlaces covalentes CC o CH de las cadenas del triglicérido, generándose una amplia variedad de radicales alquílicos que sirven como iniciadores de la cadena de reacciones responsables del deterioro del aceite, que ocurren por el mecanismo de radicales libres (Schaich, 2005); esto, por consiguiente, tiene efecto sobre la velocidad de las reacciones, y es por ello que para las mismas condiciones de humedad inicial y contenido de material no lipídico el aceite tiene el mismo nivel de deterioro en menor tiempo para los ensayos a 200 °C que a 170 °C. Por ejemplo, en los experimentos con humedad inicial del 1% y contenido de material no lipídico del 6%, el IAn, luego de 10 horas a 170 °C, es el mismo que para menos de 6 horas a 200 °C. Evaluación de la relación existente entre el IAn, la viscosidad y el color. La figura 2 señala el deterioro del aceite Frytollíquido en función del tiempo y la temperatura. En ella se confirma que al incrementarse el tiempo y la temperatura, aumenta el IAn, y que si se toma, tal y como lo propusieron Boatella y colaboradores basados en una correlación del IAn con el contenido de material no polar (Boatella et al., 2000), como valor límite de deterioro para establecer que un aceite debe reemplazarse un IAn de 156, el incremento de 30 °C reduce la vida útil del aceite en 6 horas a las condiciones descritas en el diseño de experimentos. En la figura 3 puede apreciarse la relación entre el color Lovibond rojo y el IAn durante las prueba de deterioro a 170 °C y 200 °C. Aunque a 200 °C existe un cambio radical en el color rojo, pasando de alrededor de 0,5 a 2,0 cuando el IAn supera el valor límite para el deterioro, este cambio no se observa a 170 °C. Un comportamiento similar se observa en la figura 4, pero esta vez para el color Lovibond amarillo, lo cual indica que el color es función fuerte de la temperatura. Teniendo en cuenta el amplio intervalo de la temperatura en los procesos de fritura y su poco control en las pyme, para cuantificar la correlación que existe entre el color y el deterioro del aceite se calcularon los coeficientes de determinación, R2, para los colores Lovibond rojo y amarillo incluyendo los datos a las dos temperaturas evaluadas, obteniéndose como resultado 0,558 y 0,526, respectivamente, lo que significa que la correlación existente entre el color y el deterioro es baja. Sin embargo, el análisis estadístico de los datos mostró que el efecto de temperatura sobre el color es significativo, con el 95% de nivel de confianza (p <0,05), lo que confirma el análisis cualitativo. Los resultados contrastan con los obtenidos por Paul y colaboradores (1996), quienes analizaron la viabilidad de valoración del deterioro por medio del color con resultados aceptables, aunque en su investigación no evaluaron el efecto de la temperatura en el freído. La figura 5 muestra el comportamiento de la viscosidad en función del Ian. Sin importar si la temperatura del ensayo fue de 170 o de 200 °C, cuando se alcanza el límite de deterioro, IAn de 156, hay un cambio significativo en la viscosidad, lo que se refleja en una curva sigmoidal tanto a 170 como a 200 °C, con la inflexión alrededor del límite de deterioro. En las vecindades del límite de deterioro la viscosidad a 30 °C del aceite Frytollíquido cambia de menos de 10 cP a un valor cercano a los 45 cP, y el coeficiente de correlación, R2, entre viscosidad y IAn, fue 0,809. Este valor se considera lo suficientemente alto para afirmar que, desde el punto de vista estadístico, existe correlación entre las dos variables; por otra parte, el análisis estadístico demostró que el efecto de la temperatura sobre la viscosidad no es significativo (p >0,05) en el intervalo estudiado. Tal comportamiento permite concluir que esta variable física puede usarse como indicativo del deterioro de aceites de freído en las pyme. El comportamiento de la viscosidad en función de la temperatura de freído ha sido reportado para diferentes tipos de aceites, como los de canola, maíz, girasol y sus mezclas, mostrando su viabilidad como parámetro indicador de deterioro (Santos, 2005). La figura 6 indica la viscosidad del aceite Frytollíquido con la viscosidad a 30° C, en función del tiempo y la temperatura. El límite de deterioro, IAn 156, corresponde a una viscosidad de 45 cP, tal y como se indica en la figura. En ella se confirma que, al incrementarse el tiempo de freído, hay un cambio claro en la viscosidad, más notable a 170 que a 200°C, y que el límite de deterioro se alcanza más rápidamente a mayores temperaturas de freído: alrededor de 3 horas a 200 °C y 8 horas a 170 °C, indicando que la vida útil del aceite puede prolongarse por lo menos 5 horas si el freído se hace a menores temperaturas. El cambio en la viscosidad es suficiente para que pueda apreciarse visualmente si se implementa una técnica de seguimiento del deterioro del aceite por medio de la viscosidad, haciendo una comparación con un conjunto de estándares, de manera análoga a como se realiza la medición de la viscosidad en la escala Gardner empleando viscosímetros de burbuja, como se describe la ASTM D154507. Si se empleara esta escala, la viscosidad del aceite Frytollíquido en las vecindades del límite de deterioro cambiaría de A3 a A o B en la escala Gardner Holdt. Conclusiones De las variables estudiadas, la temperatura y el tiempo tienen un efecto sobre el deterioro de un aceite de fritura estadísticamente diferente de cero con el 95% de nivel de confianza, en el intervalo de estudio. Un incremento de 30 °C en la temperatura del proceso puede disminuir hasta en 6 horas la vida útil del aceite, bajo las condiciones de prueba. Existe una correlación entre el deterioro del aceite, medido por medio del IAn, y la viscosidad, de tal forma que esta propiedad física puede emplearse para el control del deterioro del aceite Frytollíquido en las pyme. Con base en estos resultados se propone implementar una técnica comparativa similar a la que se establece en la ASTM D 154507 para la viscosidad, empleando un viscosíme metro de burbuja, cuyo costo y fácil utilización lo hace adecuado para las para las pyme. La estandarización de este método de análisis, y el análisis económico de su implementación, constituyen la siguiente fase de esta investigación. Referencias AOAC 925.10, 1990., Solids/Total Solids, Moisture, Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Agricultural Chemists (AOAC), 17th Edition, USA, 2000. AOAC 920.85, 1998., Fat/Crude Fat, Fat/Ether Extract, Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Agricultural Chemists (AOAC), 17th Edition, USA, 2000. AOAC 960.52, 1998., Elemental Analysis / Nitrogen, Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Agricultural Chemists (AOAC), 17th Edition, USA, 2000. AOAC 942.05, 1998., Ash, Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Agricultural Chemists (AOAC), 17th Edition, USA, 2000. AOAC 962.09, 1990., Fiber / Crude Fiber, Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Agricultural Chemists (AOAC) AOCS Ca 5a40 (09)., Free Fatty Acids, Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the American Oil Chemists´ Society, 6th Edition, USA, 2009. AOCS Cd 853 (03)., Peroxide Value, Acetic AcidChloroform Method, Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the American Oil Chemists´ Society, 6th Edition, USA, 2009. AOCS Cc 625 (09)., Cloud Point Test, Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the American Oil Chemists´ Society, 6th Edition, USA, 2009. AOCS Cc 13e92 (09)., Lovibond (per ISO Standard), Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the American Oil Chemists´ Society, 6th Edition, USA, 2009. ASTM D154507., Standard Test Method for Viscosity of Transparent Liquids by Bubble Time Method., American Standards for Testing Materials, USA, 2007. Benedito, J., García, J. V., Dobarganes, M., Mulet, A., Rapid Evaluation of Frying Oil Degradation Using Ultrasonic Technology., Food Research International, Vol. 40, 2007, pp. 406-414. Boatella, J., Codony, R., Rafecas, M., Guardiola, F., Recycled cooking oils: Assessment of risks for public health en European Parliament STOA Programme., Chambers, G., (ed.), European Parlament, Directorate General for Research. Luxembourgg, Septiembre, 2000., pp. 64. Choe, E., Min, D. B., Chemistry of DeepFat Frying Oils., Journal of food science., Vol. 72, No. 5, 2007, pp. R77-R86. Clark, W. L., Serbia, G. W., Safety Aspects of Frying Fats and Oils., Institute of Food Technologists., Vol. 45, No. 2, 1991, pp. 84-89. Dobarganes, M. C., Velasco, J., Márquez, R. G., La calidad de los Aceites y Grasas de Fritura., Alimentación, Nutrición y Salud., Vol. 9, No. 4, 2002, pp. 109-118. Firestone, D., Regulatory Requirements for the Frying Industry., En: Gupta, M. K., Warner, White P. J., (ed.), Frying technology and practices., AOCS Press., Champaign., 2004, pp. 200-216. Gertz, C., Chemical and Physical Parameters as a Quality Indicator of Used Frying Fats., The European Journal Lipid Science Technology., Vol. 102, No. 8, 2000, pp. 566-572. Gupta, M. K., The Effect of Oil Processing on Frying Oil Stability., En: Gupta, M. K., Warner, White P. J., (ed.), Frying technology and practices., AOCS Press., Champaign., 2004. Gupta, M. K., Frying Oils, in Bailey´s Industrial Oil and Fats Products, Edible Oil and Fat Products: Products and Applications, Fereidoon Shahidi (ed.), 6th Ed., John Wiley and Sons., New York., USA., Vol. 4, 2005. Keuneke, R., Health Destructive Effects of Frying., Total Health, Vol. 21, No.3, 1999, pp. 26-28. Navas, J.A., Optimización y Control de la Calidad y Estabilidad de Aceites y Productos de Fritura., Tesis presentada a la Universidad de Barcelona España, Facultad de Farmacia, para optar al grado de Doctor en Medicamentos, Alimentación y Salud, 2005. ICONTEC, NTC 4197, Grasas y Aceites Animales y Vegetales., Determinación del Índice de Anisidina., Equivalente a la ISO 6885:1998., Instituto Colombiano de Normas Técnicas y Certificación ICONTEC. I.C.S.: 67.200.20., Bogotá, Colombia, 2001. O´Brien, R.D., Fats and Oils: Formulating and Processing for Applications., CRC Press., 2nd ed., Boca Ratón., USA., 2004. Pokorny, J., (ed.), Yanishlieva, N., Gordon, M., Antioxidants in Food: Practical Applications., CRC Press., Woodhead Publishing Limited., Cambridge., 2001. Rosell, J. B., Frying. Improving Quality., J. B. Rosell (ed.), Cambridge, England., Woodhead Publishing Limited., 2001. Saguy, I.S., Dana, D., Integrated Approach to Deep Fat Frying: Engineering, Nutrition, Health and Consumer Aspects., Journal of Food Engineering., Vol. 56, 2003, pp. 143-152. Sahin, S., Gülum, S. S., Advances in Deep Fat Frying., Contemporary Food Engineering Series., Sun, D., (ed.), CRC press, 2008. Schaich, K., Lipid Oxidation: Theoretical Aspects, in Bailey´s Industrial Oil and Fats Products, Edible Oil and Fat Products: Chemistry, Properties and Health Effects, Fereidoon Shahidi (ed.), 6th ed., John Wiley and Sons., New York., USA., Vol. 1, 2005. Shahidi, F., (ed.), Edible oil and Fat Products: Chemistry, Properties and Health Effects., En: Bailey´s Industrial Oil and Fat Products., Vol. 1, 6th ed., Wiley Interscience, New Jersey., 2005. Santos, J., Santos, I., Souza, A., Effect of Heating and Cooling on Rheological Parameters of Edible Vegetable Oils., Journal of Food Engineering., Vol. 67, 2005, pp. 401-405. Warner, K., Chemical and Physical Reactions in Oil During Frying. En: Gupta, M. K., Warner, White P. J., (ed.), Frying technology and practices., AOCS Press., Champaign., 2004. Yagüe, M. A., Estudio de la Utilización de Aceites para Fritura en Establecimientos Alimentarios de Comidas Preparadas., Observatorio de la Seguridad Alimentaria., Septiembre, 2003., En internet: http://magno.uab.es/epsi/alimentaria/mangelesaylon.pdf. Visitada el 26 Agosto de 2008. Zakrzewski, S., Principles of Envirommental Toxicology., American Chemical Society Professional Reference Book., Washington D.C., United States of America, 1991, pp 4455.

Analysing a method for small and medium sized companies to rate oil quality during immersion frying

Efraín Hisnardo Rojas Uribe1 , Paulo César Narváez Rincón2

1 Chemical Engineering and Food Science and Technology Specialist, Univer-sidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá. ehrojasu@unal.edu.co

2M.Sc. Engineering. Ph.D. Engineering. Professor, Chemical and Environmen-tal Engineering Department, Chemical and Biochemical Processes Group, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá. pcnarvaezr@unal.edu.co

ABSTRACT

This work studied the deterioration of commercial Frytol oil in controlled frying conditions using the anisidine index (AI) as standard evaluation method. The effect of tempera-ture and time was studied at 170°C for up to 10 hours and at 200°C for up to 6 hours in the presence of factors which speeded up oil deterioration: 1% and 8% water based on the mass of oil and non-lipid material, 1% and 6% based on the mass of oil. Air flow rate was kept con-stant at 25 L h-1. The relationship between AI, colour and viscosity was studied to evaluate the technical viability of measuring these variables as a function of time to be used as a method for rating oil deterioration by small and me-dium sized enterprises (SME). Oil deterioration was higher and faster at maximum study interval values for each ex-perimental factor, although only the effect of temperature was significant (p<0.05). Red and yellow on the Lovibond scale were weakly related (AI R2=0.558 and R2=0.526, respectively), colour depending on frying temperature. Viscosity measured at 30°C had the highest coefficient of determination (R2=0.809) and was independent of frying temperature. Viscosity is thus a variable which can be used for determining frying oil deterioration in SME as a conse-quence of a significant change from 10 cP to 45 cP which is closer to frying oil deterioration limit (AI 156). It can facilitate determination and lower associated costs, there-by improving product quality and customer confidence in them.

Keywords: immersed frying, viscosity, Lovibond colour, anisidine value, oil deterioration.

Received: October 05th 2009. Accepted: December 31th 2010

Introduction

Frying refers to cooking food by immersing it in hot oil or fat for a specified period, usually in the presence of air, where the oil acts as a medium for heat and mass transfer thereby producing fast and homogeneous heating of a product (Navas, 2005; Yagüe, 2003) and giving unique crispness, flavour and colour which is highly desired by consumers (Gupta, 2004; Choe, 2007). These characteristics are mainly due to different reactions occurring in the frying oil and the food itself which are produced by lipid oxidation compounds and Maillard reaction products (Navas, 2005).

Frying food is cooked during immersion by direct heat transfer from the hot oil to the cold food; oil temperature decreases when food is added to hot oil and moisture on food surface quickly changes from liquid phase to vapour phase, while water inside food diffuses to the surface, to finally reach vapour phase and travel through the frying oil to the air as shown by the presence of bubbles within the oil. Food starts to obtain its characteristic colour as frying advances a and oil is absorbed into the food, conferring a crunchy texture and its characteristic flavour (Gupta, 2004).

Factors such as high temperature and the presence of oxygen and water in the oil produce irreversible physical changes such as increased viscosity, colour and foaming, decreased smoke point and chemical reactions, including oxidation, hydrolysis and polymerisation, these being factors which promote oil deterioration (O'Brien, 2004; Saguy and Dana, 2003; Dobarganes, 2002, Sontag 1982). A high degree of oil deterioration can have negative effects on human health because some products having undesirable chemical reactions can act as enzyme inhibitors, vitamin destroyers, gastrointestinal irritants and/or mutagenic agents (Clark and Serbia, 1991, Zakrzewski, 1991; Keuneke, 1999).

Some studies have measured peroxide value, acid value, nonpolar material content, AI, polymer content, iodine value, thiobarbituric acid value or conjugated diene to determine the degree of oil deterioration (Pokorny et al., 2001; Navas, 2005, Gupta, 2004; Rosell, 2001; Shahidi, 2005); nonpolar material and AI are most commonly used for reliability and relationship to deterioration but they are difficult to implement in SME because of the highly specialised equipment needed, the technical background for personnel required for such analysis and higher associated costs (Benedito et al., 2007). AI measures the amount of α and β;unsaturated aldehydes present in oil; it measures secondary oxidation or oil’s history (O’Brien, 2004).

Some countries have established regulations to protect consumers from the risk of consuming food fried in deteriorated oils where the limit determining whether an oil cannot be used in food production corresponds to 25% polar material content (Firestone, 2004; Shahidi, 2005; Gertz, 2000, Sahin et al., 2008), i.e. equivalent to 156 AI (Boatella et al., 2000).

Currently there are no practical and objective systems for evaluating the deterioration of frying oil in SME because standardised methods for analysing frying oils use equipment and procedures involving cost, time and technologies beyond the reach of such companies (Navas, 2005; Benedito, 2007). The rapid test systems which are used in Europe and the USA have not become widespread in LatinAmerica because the necessary equipment is very expensive regarding SME budgets.

Accordingly, this research has studied a practical method for SMEs determining frying oil deterioration limit to facilitate monitoring frying oil quality in such companies which will help standardise processes and improve food´s organoleptic characteristics, thereby promoting quality and consumer confidence in their products. Sociedad Industrial de Grasas Vegetales (C.I. SIGRA SA), which refines and produces cooking and frying oil, aims to increase the added value of their product Frytollíquido by providing technical support for its customers by developing this work.

The effect of temperature, time, initial moisture content and nonlipid material on Frytolliquid oil deterioration was studied during controlled frying at constant air flow rate and using AI for measuring deterioration. The relationship of AI with colour and viscosity was then established to determine its feasibility as a method for SME to rate frying oil deterioration. Selecting these two variables was based on the relationship between them and deterioration (Gupta, 2005), and the possibility of implementing easily applied procedures in SME where measurement would consist of comparison with predefined standards (i.e. Gardner colour and viscosity scales) used in industries such as resins, paints and coatings. This type of characterisation reduces the cost of equipment and analysis and the technical background required by the personnel in charge is low.

Materials and Methods

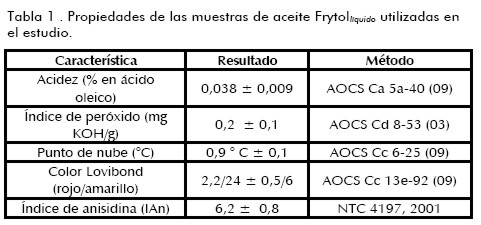

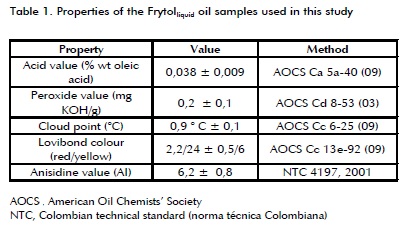

Materials. A sample of fresh Frytollquid oil (a mixture of soybean oil and palm olein) produced by C.I. SIGRA S.A. (Bogotá, Colombia) was used. The sample was a mixture of eleven random samples. The oil sample was characterised by acid value (AOCS Ca5a40 (09)), peroxide value (AOCS Cd853 (03)), cloud point (AOCS Cc625 (09)), red and yellow Lovibond colour with 5 "¼ cell (AOCS Cc13e92 (09)) and AI (NTC 4197, 2001). Table 1 shows average characterisation results where the value of each sample´s properties was measured in triplicate (results in Table 1 are thus the average of 33 data items).

Nonlipid material was prepared from thirteen samples randomly taken from raw pie crust, obtained from Empanadas de la Cima Ltda (Bogotá, Colombia), homogenised by maceration and characterised by proximate analysis, as shown in Table 2.

4methoxyaniline (pAnisidine) and sodium sulphate anhydrous from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) and 2,2,4trimethyl pentane from Mallinckrodt Baker Inc. (Phillipsburg, USA), were used for determining the AI. pAnisidine was purified following the procedure described in NTC 4197.

Methods. AI was measured according to the procedure described in NTC 4197, using a Perkin Elmer Model Lambda 3B visible light pectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer Inc., Massachusetts, USA) with 10 mm cell. The procedure established in AOCS Cc 13e92 was followed for measuring Lovibond colour using a Lovibond Colourimeter PFX 880 (The Tintometer Ltd, Wiltshire, UK) with 10 mm cell at 50°C.

Viscosity was measured according to the procedure described in ASTM D2196 in a Brookfield VISCO 20 concentric cylinder rotational viscometer (Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, UK) using a RV / HA # 3 302S/ S33 needle at 30°C.

Experimental design. The effect of temperature, the presence of nonlipid material, time and humidity on Frytol lquid frying oil deterioration was studied by designing a multifactorial experiment for three variables at two levels and for one variable at three levels, as follows: 1% and 6% wt nonlipid material, 1% and 8% wt moisture, both based on the mass of the oil, 170°C and 200°C frying temperature, and time by sampling at 6, 8 and 10 hours for the 170°C test and at 4, 5 and 6 hours for the 200° C test. The higher the frying temperature, the higher the rate of reactions associated with deterioration; such pattern explained why test time was shorter at 200°C than 170°C. 24 tests were performed for studying these variables´ effect (each conducted twice). Frying was controlled using RANCIMAT 679 (Metrohm AG, Switzerland) equipment, keeping system air flow rate constant at 25 L h1.

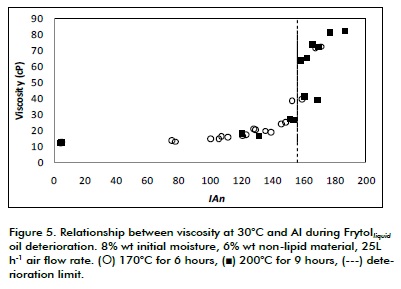

Tests were performed at 170°C for 9 hours and 200°C for 6 hours in controlled frying conditions in a RANCIMAT 679 (Metrohm AG, Switzerland) to determine the relationship between AI, viscosity and colour deterioration using 6% wt nonlipid material, 8% wt moisture and 25 L h1 air flow rate. The volume of oil used in each test was 70 ml. Samples were taken every hour and tests were conducted twice. Each sample was analysed for AI, dynamic viscosity and Lovibond colour.

The results were statistically analysed with STATGRAPHICS Centurion XV version 15.2.06 (StatPoint Inc. Virginia, USA).

Results and analysis

Evaluating frying oil deterioration by AI. Statistical analysis of the results from the experiment which evaluated the effect of time, temperature, moisture and nonlipid material on oil deterioration (ANOVA) showed that only the effects of time and temperature on AI were significantly different from zero at 95% confidence level (p<0.05) and an increase in these variables´ value increased frying oil deterioration.

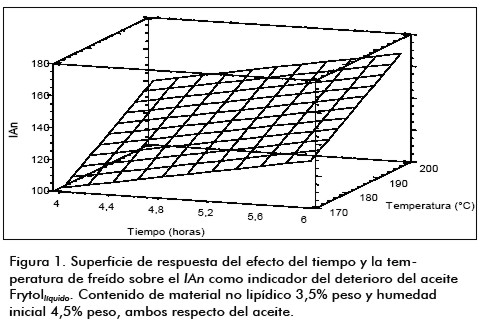

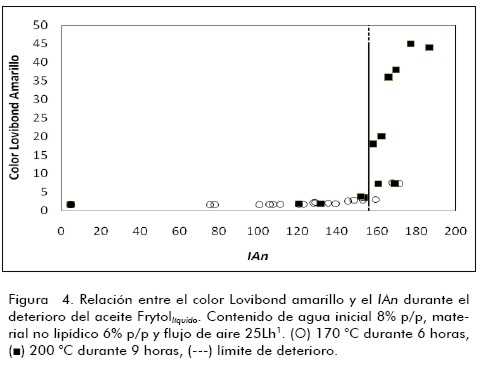

Figures 1 shows the effect of time and temperature on AI, while Figure 2 shows the effect of initial moisture and nonlipid material on AI. Two of the variables being studied were parameterised regarding the average value of the range studied in each Figure, even though the pattern was qualitatively similar throughout the range.

Figure 1 shows that increasing frying temperature led to increased deterioration of frying oil, confirming Gupta (2004) and Saguy´s (2003) research in which they reported that if this variable were controlled then oil life would be extended. Deterioration increased with a rise in temperature because there was enough energy to eak the CC and CH covalent bonds in triglyceride, producing a wide variety of alkyl radicals acting as initiators for the chain reactions responsible for the deterioration of oil occurring through a free radicals mechanism (Schaich, 2005). This has an effect on reaction rate and this is why the oil had the same deterioration level in less time for tests at 200°C than 170°C, for the same initial moisture and nonlipid material conditions. For example, AI after 10 hours at 170°C was the same as less than 6 hours at 200°C in experiments with 1% wt initial moisture and 6% wt non lipid material.

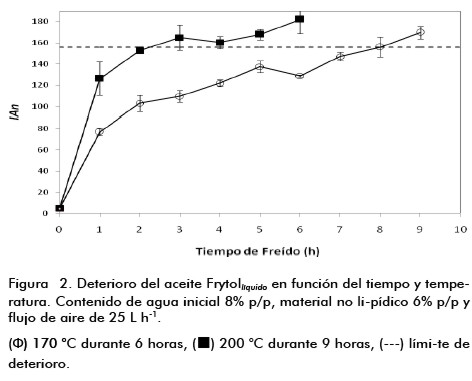

Evaluating the relationship between AI, viscosity and colour. Figure 2 shows Frytollíquido oil deterioration regarding time and temperature. It confirms that AI increased by increasing time and temperature and that if, as has been reported by Boatella et al., based on a correlation between AI and nonpolar material content (Boatella et al., 2000), then the limiting value for establishing when an oil should be replaced would be 156 AI; a 30°C increase reduced the oil´s lifetime by 6 hours in experimental design conditions.

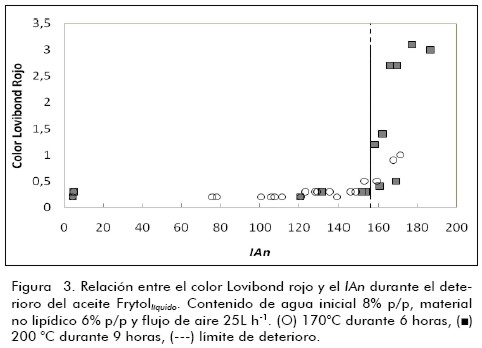

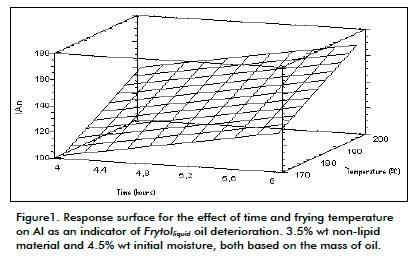

Figure 3 shows the relationship between Lovibond red and AI during deterioration tests at 170°C and 200°C. Although there was a radical change in Lovibond red at 200°C from about 0.5 to 2.0 when AI exceeded deterioration limit value, such change was not observed at 170°C.

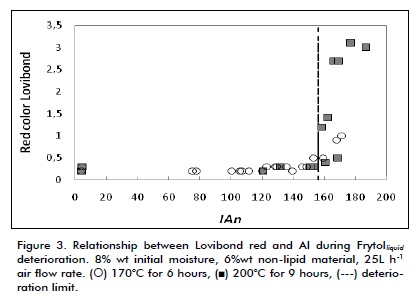

A similar pattern can be observed in Figure 4, but this time for Lovibond yellow, indicating that Lovibond colour was related to temperature. The coefficient of determination (R22) was calculated for Lovibond red and yellow, given the wide frying temperature range and the little control which SME can exert over this variable in quantifying the relationship between colour and oil deterioration. This included data regarding both temperatures tested (0.558 and 0.526, respectively) meaning that the relationship between colour and oil deterioration was low. However, statistical analysis showed that effect of temperature on colour was significantly different from zero at 95% confidence level (p<0.05), thereby confirming qualitative analysis.

This study’s results were different to those obtained by Paul et al., (1996) who analysed the feasibility of determining oil deterioration through colour; they obtained acceptable results, although their research did not study the effect of frying temperature.

According to the results, SME following frying oil deterioration by using colour is not an appropriate technique.

Figure 5 shows viscosity regarding AI. It can be noticed in this Figure that there was a significant change in viscosity when deterioration limit value was reached (156 AI), despite temperature, which was reflected in a sigmoidal curve at 170°C and 200°C, inflection point being closer to deterioration limit. Frytolliquid oil viscosity at 30°C changed from less than 10 cP to around 45 cP and determination coefficient (R2) between viscosity and AI was 0.809. This coefficient´s value was considered high enough to state that there was a statistical relationship between AI and viscosity. Statistical analysis showed that temperature had no significant effect on viscosity in the range being studied (p>0.05). Such pattern led to concluding that viscosity is an appropriate variable for SME to monitor the deterioration of oil.

Behavior of viscosity as a function of frying temperature has been reported for different oils, as rapeseed oil, corn oil, sunflower oil and their mixtures, showing its feasibility as indicator variable of deterioration of oil (Santos, 2005).

Figure 6 shows FRYTOLliquid oil deterioration related to viscosity at 30ºC regarding time and temperature. Deterioration limit corresponded to 45 cP viscosity. Figure 6 confirms that when frying time was increased there was a clear change in viscosity which was more noticeable at 170°C than at 200°C and that deterioration limit was reached first at the higher temperature (about 3 hours at 200°C and 8 hours at 170°C).

The change in viscosity was enough to establish the deterioration of oil through viscosity if a comparisonbased technique having a set of standards were to be implemented, similar to the viscosity measurement method used in the Gardner bubble viscometer range (ASTM D154507). If the Gardner Holdt scale were to be used, then FRYTOLliquid oil viscosity (closer to oil´s deterioration limit value) would change from A3 to A or B.

Conclusions

Temperature and time had an effect on frying oil deterioration significantly different from zero (95% confidence level) in the range studied here. A 30°C increase in frying temperature reduced oil life by up to 6 hours in the conditions used in this research. There was a correlation between the deterioration of oil, measured by AI, and viscosity so that SME could use this physical property to control oil deterioration. Based on thes results, it is proposed that SME should adopt a comparative technique (similar to that described in ASTM D 154507) for ascertaining viscosity using a bubble viscometer whose cost and ease of use would be suitable for SME. Standardising the method and its economic assessment form the second stage for this research.

Referencias

AOAC 925.10, 1990., Solids/Total Solids, Moisture, Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Agricultural Chemists (AOAC), 17th Edition, USA, 2000.

AOAC 920.85, 1998., Fat/Crude Fat, Fat/Ether Extract, Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Agricultural Chemists (AOAC), 17th Edition, USA, 2000.

AOAC 960.52, 1998., Elemental Analysis / Nitrogen, Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Agricultural Chemists (AOAC), 17th Edition, USA, 2000.

AOAC 942.05, 1998., Ash, Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Agricultural Chemists (AOAC), 17th Edition, USA, 2000.

AOAC 962.09, 1990., Fiber / Crude Fiber, Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Agricultural Chemists (AOAC)

AOCS Ca 5a40 (09)., Free Fatty Acids, Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the American Oil Chemists´ Society, 6th Edition, USA, 2009.

AOCS Cd 853 (03)., Peroxide Value, Acetic AcidChloroform Method, Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the American Oil Chemists´ Society, 6th Edition, USA, 2009.

AOCS Cc 625 (09)., Cloud Point Test, Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the American Oil Chemists´ Society, 6th Edition, USA, 2009.

AOCS Cc 13e92 (09)., Lovibond (per ISO Standard), Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the American Oil Chemists´ Society, 6th Edition, USA, 2009.

ASTM D154507., Standard Test Method for Viscosity of Transparent Liquids by Bubble Time Method., American Standards for Testing Materials, USA, 2007.

Benedito, J., García, J. V., Dobarganes, M., Mulet, A., Rapid Evaluation of Frying Oil Degradation Using Ultrasonic Technology., Food Research International, Vol. 40, 2007, pp. 406-414.

Boatella, J., Codony, R., Rafecas, M., Guardiola, F., Recycled cooking oils: Assessment of risks for public health en European Parliament STOA Programme., Chambers, G., (ed.), European Parlament, Directorate General for Research. Luxembourgg, Septieme, 2000., pp. 64.

Choe, E., Min, D. B., Chemistry of DeepFat Frying Oils., Journal of food science., Vol. 72, No. 5, 2007, pp. R77-R86.

Clark, W. L., Serbia, G. W., Safety Aspects of Frying Fats and Oils., Institute of Food Technologists., Vol. 45, No. 2, 1991, pp. 84-89.

Dobarganes, M. C., Velasco, J., Márquez, R. G., La calidad de los Aceites y Grasas de Fritura., Alimentación, Nutrición y Salud., Vol. 9, No. 4, 2002, pp. 109-118.

Firestone, D., Regulatory Requirements for the Frying Industry., En: Gupta, M. K., Warner, White P. J., (ed.), Frying technology and practices., AOCS Press., Champaign., 2004, pp. 200-216.

Gertz, C., Chemical and Physical Parameters as a Quality Indicator of Used Frying Fats., The European Journal Lipid Science Technology., Vol. 102, No. 8, 2000, pp. 566-572.

Gupta, M. K., The Effect of Oil Processing on Frying Oil Stability., En: Gupta, M. K., Warner, White P. J., (ed.), Frying technology and practices., AOCS Press., Champaign., 2004.

Gupta, M. K., Frying Oils, in Bailey´s Industrial Oil and Fats Products, Edible Oil and Fat Products: Products and Applications, Fereidoon Shahidi (ed.), 6th Ed., John Wiley and Sons., New York., USA., Vol. 4, 2005.

Keuneke, R., Health Destructive Effects of Frying., Total Health, Vol. 21, No.3, 1999, pp. 26-28.

Navas, J.A., Optimización y Control de la Calidad y Estabilidad de Aceites y Productos de Fritura., Tesis presentada a la Universidad de Barcelona España, Facultad de Farmacia, para optar al grado de Doctor en Medicamentos, Alimentación y Salud, 2005.

ICONTEC, NTC 4197, Grasas y Aceites Animales y Vegetales., Determinación del Índice de Anisidina., Equivalente a la ISO 6885:1998., Instituto Colombiano de Normas Técnicas y Certificación ICONTEC. I.C.S.: 67.200.20., Bogotá, Colombia, 2001.

O´Brien, R.D., Fats and Oils: Formulating and Processing for Applications., CRC Press., 2nd ed., Boca Ratón., USA., 2004.

Pokorny, J., (ed.), Yanishlieva, N., Gordon, M., Antioxidants in Food: Practical Applications., CRC Press., Woodhead Publishing Limited., Camidge., 2001.

Rosell, J. B., Frying. Improving Quality., J. B. Rosell (ed.), Camidge, England., Woodhead Publishing Limited., 2001.

Saguy, I.S., Dana, D., Integrated Approach to Deep Fat Frying: Engineering, Nutrition, Health and Consumer Aspects., Journal of Food Engineering., Vol. 56, 2003, pp. 143-152.

Sahin, S., Gülum, S. S., Advances in Deep Fat Frying., Contemporary Food Engineering Series., Sun, D., (ed.), CRC press, 2008.

Schaich, K., Lipid Oxidation: Theoretical Aspects, in Bailey´s Industrial Oil and Fats Products, Edible Oil and Fat Products: Chemistry, Properties and Health Effects, Fereidoon Shahidi (ed.), 6th ed., John Wiley and Sons., New York., USA., Vol. 1, 2005.

Shahidi, F., (ed.), Edible oil and Fat Products: Chemistry, Properties and Health Effects., En: Bailey´s Industrial Oil and Fat Products., Vol. 1, 6th ed., Wiley Interscience, New Jersey., 2005.

Santos, J., Santos, I., Souza, A., Effect of Heating and Cooling on Rheological Parameters of Edible Vegetable Oils., Journal of Food Engineering., Vol. 67, 2005, pp. 401-405.

Warner, K., Chemical and Physical Reactions in Oil During Frying. En: Gupta, M. K., Warner, White P. J., (ed.), Frying technology and practices., AOCS Press., Champaign., 2004.

Yagüe, M. A., Estudio de la Utilización de Aceites para Fritura en Establecimientos Alimentarios de Comidas Preparadas., Observatorio de la Seguridad Alimentaria., Septieme, 2003., En internet: http://magno.uab.es/epsi/alimentaria/mangelesaylon.pdf. Visitada el 26 Agosto de 2008.

Zakrzewski, S., Principles of Envirommental Toxicology., American Chemical Society Professional Reference Book., Washington D.C., United States of America, 1991, pp 4455.

References

AOAC 925.10, 1990., Solids/Total Solids, Moisture, Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Agricultural Chemists (AOAC), 17th Edition, USA, 2000.

AOAC 920.85, 1998., Fat/Crude Fat, Fat/Ether Extract, Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Agricultural Chemists (AOAC), 17th Edition, USA, 2000.

AOAC 960.52, 1998., Elemental Analysis / Nitrogen, Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Agricultural Chemists (AOAC), 17th Edition, USA, 2000.

AOAC 942.05, 1998., Ash, Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Agricultural Chemists (AOAC), 17th Edition, USA, 2000.

AOAC 962.09, 1990., Fiber / Crude Fiber, Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Agricultural Chemists (AOAC)

AOCS Ca 5a40 (09)., Free Fatty Acids, Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the American Oil Chemists´ Society, 6th Edition, USA, 2009.

AOCS Cd 853 (03)., Peroxide Value, Acetic AcidChloroform Method, Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the American Oil Chemists´ Society, 6th Edition, USA, 2009.

AOCS Cc 625 (09)., Cloud Point Test, Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the American Oil Chemists´ Society, 6th Edition, USA, 2009.

AOCS Cc 13e92 (09)., Lovibond (per ISO Standard), Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the American Oil Chemists´ Society, 6th Edition, USA, 2009.

ASTM D154507., Standard Test Method for Viscosity of Transparent Liquids by Bubble Time Method., American Standards for Testing Materials, USA, 2007.

Benedito, J., García, J. V., Dobarganes, M., Mulet, A., Rapid Evaluation of Frying Oil Degradation Using Ultrasonic Technology., Food Research International, Vol. 40, 2007, pp. 406-414. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2006.10.017

Boatella, J., Codony, R., Rafecas, M., Guardiola, F., Recycled cooking oils: Assessment of risks for public health en European Parliament STOA Programme., Chambers, G., (ed.), European Parlament, Directorate General for Research. Luxembourgg, Septiembre, 2000., pp. 64.

Choe, E., Min, D. B., Chemistry of Deep-Fat Frying Oils., Journal of food science., Vol. 72, No. 5, 2007, pp. R77-R86. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00352.x

Clark, W. L., Serbia, G. W., Safety Aspects of Frying Fats and Oils., Institute of Food Technologists., Vol. 45, No. 2, 1991, pp. 84-89.

Dobarganes, M. C., Velasco, J., Márquez, R. G., La calidad de los Aceites y Grasas de Fritura., Alimentación, Nutrición y Salud., Vol. 9, No. 4, 2002, pp. 109-118.

Firestone, D., Regulatory Requirements for the Frying Industry., En: Gupta, M. K., Warner, White P. J., (ed.), Frying technology and practices., AOCS Press., Champaign., 2004, pp. 200-216.

Gertz, C., Chemical and Physical Parameters as a Quality Indicator of Used Frying Fats., The European Journal Lipid Science Technology., Vol. 102, No. 8, 2000, pp. 566-572. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/1438-9312(200009)102:8/9<566::AID-EJLT566>3.0.CO;2-B

Gupta, M. K., The Effect of Oil Processing on Frying Oil Stability., En: Gupta, M. K., Warner, White P. J., (ed.), Frying technology and practices., AOCS Press., Champaign., 2004.

Gupta, M. K., Frying Oils, in Bailey´s Industrial Oil and Fats Products, Edible Oil and Fat Products: Products and Applications, Fereidoon Shahidi (ed.), 6th Ed., John Wiley and Sons., New York., USA., Vol. 4, 2005. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/047167849X.bio023

Keuneke, R., Health Destructive Effects of Frying., Total Health, Vol. 21, No.3, 1999, pp. 26-28.

Navas, J.A., Optimización y Control de la Calidad y Estabilidad de Aceites y Productos de Fritura., Tesis presentada a la Universidad de Barcelona España, Facultad de Farmacia, para optar al grado de Doctor en Medicamentos, Alimentación y Salud, 2005.

ICONTEC, NTC 4197, Grasas y Aceites Animales y Vegetales., Determinación del Índice de Anisidina., Equivalente a la ISO 6885:1998., Instituto Colombiano de Normas Técnicas y Certificación ICONTEC. I.C.S.: 67.200.20., Bogotá, Colombia, 2001.

O´Brien, R.D., Fats and Oils: Formulating and Processing for Applications., CRC Press., 2nd ed., Boca Ratón., USA., 2004.

Pokorny, J., (ed.), Yanishlieva, N., Gordon, M., Antioxidants in Food: Practical Applications., CRC Press., Woodhead Publishing Limited., Cambridge., 2001. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1201/9781439823057

Rosell, J. B., Frying. Improving Quality., J. B. Rosell (ed.), Cambridge, England., Woodhead Publishing Limited., 2001.

Saguy, I.S., Dana, D., Integrated Approach to Deep Fat Frying: Engineering, Nutrition, Health and Consumer Aspects., Journal of Food Engineering., Vol. 56, 2003, pp. 143-152. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0260-8774(02)00243-1

Sahin, S., Gülum, S. S., Advances in Deep Fat Frying., Contemporary Food Engineering Series., Sun, D., (ed.), CRC press, 2008.

Schaich, K., Lipid Oxidation: Theoretical Aspects, in Bailey´s Industrial Oil and Fats Products, Edible Oil and Fat Products: Chemistry, Properties and Health Effects, Fereidoon Shahidi (ed.), 6th ed., John Wiley and Sons., New York., USA., Vol. 1, 2005. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/047167849X.bio067

Shahidi, F., (ed.), Edible oil and Fat Products: Chemistry, Properties and Health Effects., En: Bailey´s Industrial Oil and Fat Products., Vol. 1, 6th ed., Wiley Interscience, New Jersey., 2005. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/047167849X

Santos, J., Santos, I., Souza, A., Effect of Heating and Cooling on Rheological Parameters of Edible Vegetable Oils., Journal of Food Engineering., Vol. 67, 2005, pp. 401-405. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2004.05.007

Warner, K., Chemical and Physical Reactions in Oil During Frying. En: Gupta, M. K., Warner, White P. J., (ed.), Frying technology and practices., AOCS Press., Champaign., 2004.

Yagüe, M. A., Estudio de la Utilización de Aceites para Fritura en Establecimientos Alimentarios de Comidas Preparadas., Observatorio de la Seguridad Alimentaria., Septiembre, 2003., En internet: http://magno.uab.es/epsi/alimentaria/mangelesaylon.pdf. Visitada el 26 Agosto de 2008.

Zakrzewski, S., Principles of Envirommental Toxicology., American Chemical Society Professional Reference Book., Washington D.C., United States of America, 1991, pp 4455.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Ana Letícia Kincheski Coelho, Marcos de Andrade Barbosa Guilherme, Rilton Alves de Freitas, Marcos R. Mafra, Luciana Igarashi Mafra. (2026). Tunable oleogels from sunflower oil, ethylcellulose, and quillaja saponin: Synergistic interactions, structural properties, and oxidative stability. Food Hydrocolloids, 170, p.111744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2025.111744.

2. Luz A. Rincón, Juan G. Cadavid, Alvaro Orjuela. (2019). Used cooking oils as potential oleochemical feedstock for urban biorefineries – Study case in Bogota, Colombia. Waste Management, 88, p.200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2019.03.042.

3. Silvia Álvarez Graña, Daniel Abarquero, Julio Claro, Patricia Combarros-Fuertes, José María Fresno, M. Eugenia Tornadijo. (2025). Behaviour of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) oil and high oleic sunflower oil during the frying of churros. Food Chemistry Advances, 6, p.100899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.focha.2025.100899.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

Copyright (c) 2011 Efraín Hisnardo Rojas Uribe, Paulo César Narváez Rincón

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The authors or holders of the copyright for each article hereby confer exclusive, limited and free authorization on the Universidad Nacional de Colombia's journal Ingeniería e Investigación concerning the aforementioned article which, once it has been evaluated and approved, will be submitted for publication, in line with the following items:

1. The version which has been corrected according to the evaluators' suggestions will be remitted and it will be made clear whether the aforementioned article is an unedited document regarding which the rights to be authorized are held and total responsibility will be assumed by the authors for the content of the work being submitted to Ingeniería e Investigación, the Universidad Nacional de Colombia and third-parties;

2. The authorization conferred on the journal will come into force from the date on which it is included in the respective volume and issue of Ingeniería e Investigación in the Open Journal Systems and on the journal's main page (https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/ingeinv), as well as in different databases and indices in which the publication is indexed;

3. The authors authorize the Universidad Nacional de Colombia's journal Ingeniería e Investigación to publish the document in whatever required format (printed, digital, electronic or whatsoever known or yet to be discovered form) and authorize Ingeniería e Investigación to include the work in any indices and/or search engines deemed necessary for promoting its diffusion;

4. The authors accept that such authorization is given free of charge and they, therefore, waive any right to receive remuneration from the publication, distribution, public communication and any use whatsoever referred to in the terms of this authorization.