The current state of nonconventional sources of energy and related perspectives

Fuentes convencionales y no convencionales de energía: estado actual y perspectivas

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/ing.investig.v30n3.18189Keywords:

energy, non-conventional energy source, biomass, biofuel (en)energía, fuentes no convencionales de energía, biomasa, biocombustibles (es)

Downloads

This article presents an overview of world and Colombian energy sources, including distribution, production and consumption by fuel and end-user sectors, respectively, as well as a brief description of some non-conventional energy sources (NCES), pointing out those classified as bioenergy and used as non-conventional fuels in the transport and electricity generating sectors. Colombian policies for promoting the rational use of energy (RUE) and NCES are presented and their targets are compared to some established by the European Union and the USA.

Este artículo presenta un panorama mundial y nacional de las fuentes de energía y la distribución de su uso por tipo de combustible y los sectores a los que se destina. Describe algunas fuentes no convencionales de energía, haciendo énfasis en algunas cifras de aquellas que se clasifican como bioenergía y que se utilizan en mayor porcentaje en el transporte y en la generación de energía eléctrica. Introduce las políticas colombianas para el fomento del uso racional de la energía (URE) y las fuentes de energía no convencionales (FENC) y compara las metas colombianas con las que plantean la Comunidad Económica Europea y Estados Unidos.

Paulo César Narváez Rincón1

1 Ingeniero Químico. M.Sc., en Ingeniería. Ph.D., en ingeniería, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia. Grupo de Investigación en Procesos Químicos y Bioquímicos, Departamento de Ingeniería Química y Ambiental, Universidad Nacional de Colombia. pcnarvaezr@bt.unal.edu.co

RESUMEN

Este artículo presenta un panorama mundial y nacional de las fuentes de energía y la distribución de su uso por tipo de combustible y los sectores a los que se destina. Describe algunas fuentes no convencionales de energía, haciendo énfasis en algunas cifras de aquellas que se clasifican como bioenergía y que se utilizan en mayor porcentaje en el transporte y en la generación de energía eléctrica. Introduce las políticas colombianas para el fomento del uso racional de la energía (URE) y las fuentes de energía no convencionales (FENC) y compara las metas colombianas con las que plantean la Comunidad Económica Europea y Estados Unidos.

Palabras claves: energía, fuentes no convencionales de energía, biomasa, biocombustibles.

ABSTRACT

This article presents an overview of world and Colombian energy sources, including distribution, production and consumption by fuel and end-user sectors, respectively, as well as a brief description of some non-conventional energy sources (NCES), pointing out those classified as bioenergy and used as non-conventional fuels in the transport and electricity generating sectors. Colombian policies for promoting the rational use of energy (RUE) and NCES are presented and their targets are compared to some established by the European Union and the USA.

Key words: energy, non-conventional energy source, biomass, biofuel.

Recibido: septiembre 4 de 2010

Aceptado: noviembre 15 de 2010

Introducción

La reciente publicación de la resolución 180919 del Ministerio de Minas y Energía, en la que se presenta el plan de acción para desarrollar un programa sobre el uso racional de la energía (URE) y demás fuentes de energía no convencionales (FENC) en Colombia, hace parte de un conjunto de iniciativas de Gobiernos de los cinco continentes que buscan con ellas contribuir a la solución de algunos de los problemas más importantes a los que se enfrenta la sociedad del siglo XXI: la dependencia del petróleo como principal fuente de energía y materia prima para muchos productos químicos, el carácter finito de este recurso natural, el impacto negativo sobre el medio ambiente de la generación de energía, y el desempleo y bajo desarrollo rural.

Con las FENC pretenden incrementar la seguridad e independencia energética, reducir la emisión de gases de efecto invernadero (GHG, por sus iniciales en inglés) e incrementar la competitividad de la economía, especialmente en los países en vías de desarrollo, donde más se necesita debido a los altos índices de desempleo y pobreza que obligan a la población a trasladarse a las grandes ciudades, en una forma de migración interna, o a otros países para buscar un mejor nivel de vida, especialmente a Estados Unidos, Europa y Australia.

La biomasa, el sol, el viento, las olas, el agua y el interior de la tierra, son fuentes de energía que se utilizan con diferentes niveles de madurez tecnológica, o que podrán usarse para reemplazar gradualmente al petróleo como la principal fuente de energía. Aunque todas ellas vienen empleándose, el empleo del agua para la generación de energía eléctrica y de biomasa para producir biocombustibles son los más extendidos, dada su disponibilidad, madurez tecnológica y, en el caso de los biocombustibles líquidos, la posibilidad de implementarlos sin modificar los motores de combustión interna a gasolina o diesel de los vehículos actuales.

En este artículo se presenta un panorama mundial y nacional de las fuentes de energía y la distribución de su uso por tipo de combustible y los sectores a los que se destina. Se describen de forma sucinta algunas FNCE y se especifican aquellas que se clasifican como bioenergía. Posteriormente, se describen las políticas colombianas para el fomento del URE y las FENC y se comparan con algunas metas de la Comunidad Económica Europea y con los actos legislativos de los Estados Unidos. Finalmente se plantea, a manera de conclusión, el papel que puede jugar la academia en el desarrollo e implementación de estas fuentes de energía.

Panorama de la energía

De acuerdo con la Administración de Información de la Energía de los Estados Unidos (EIA, por sus siglas en inglés), el consumo mundial de energía en 2007 fue de 495,2 × 1015 BTU, y se espera un crecimiento anual del 1,4% hasta el año 2035, mayor en los países que no son miembros de la Organización para la Cooperación Económica y el Desarrollo2 (US Energy Information Administration, 2010). Los combustibles líquidos, que incluyen el petróleo y sus derivados, etanol, biodiesel y productos de licuefacción del carbón y el gas, constituyen la principal fuente de energía y aportaron alrededor de 85 cuatrillones de BTU en 2007, 35% del total, aunque se espera que su participación se reduzca al 30% en 2035 (US Energy Information Administration, 2010). Por otra parte, la Agencia Internacional de la Energía (IAE, por sus siglas en inglés), prevé que la demanda mundial de energía pasará de 12.0003millones de toneladas equivalentes de petróleo (tep) en 2007, a 16.800 tep en 2030, es decir, un incremento del 40% (International Energy Agency, 2009). En 2007 los países de Centro y Suramérica consumieron tan sólo 5,6% de la energía mundial, participación que se incrementará a 5,9% y 6,2% en 2015 y 2035, respectivamente (US Energy Information Administration, 2010). De acuerdo con la British Petroleum Company (2010), el consumo mundial de energía primaria en 2009 fue de 11.164 millones de tep, 29 de ellos en Colombia, que son menos del 0,26% del total.

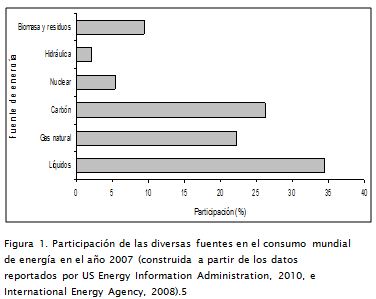

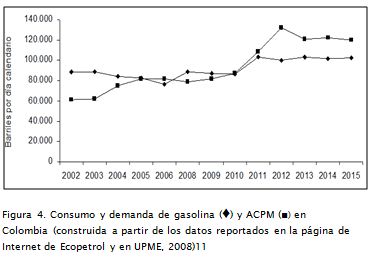

La Figura 1 muestra la distribución porcentual de las diferentes fuentes de energía en el consumo mundial para 2007. En ella se observa que los combustibles fósiles son la mayor fuente de energía, y entre ellos los líquidos aportan 35% y el carbón 27%. En 2009, 34,8% de la energía primaria provino del petróleo, 23,8% del gas natural y 29,4% del carbón (British Petroleum Company, 2010). Aunque para Colombia la situación es similar y el petróleo aportó 30,3%, una diferencia notable con respecto al comportamiento mundial consiste en que la hidroelectricidad aportó 32,1%, y el carbón, a pesar de las reservas con las que cuenta el país, tan sólo 10,7% (British Petroleum Company, 2010).

En el año 2005 el consumo de energía primaria en Colombia fue de 1.134,7 × 1012 BTU, 24% más que en 1990, y la oferta se distribuyó de la siguiente forma de acuerdo con su fuente (UPME, 2007): el petróleo aportó 48%, el gas natural 21%, la hidroenergía 12% y la leña y el carbón 5,5%. Por otra parte, el consumo para el mismo año tuvo la siguiente distribución: gasolina, ACPM y otros derivados del petróleo 48%, energía eléctrica 19%, gas natural 15%, carbón 8%, leña y bagazo 7% y otras fuentes 3% (UPME, 2007).

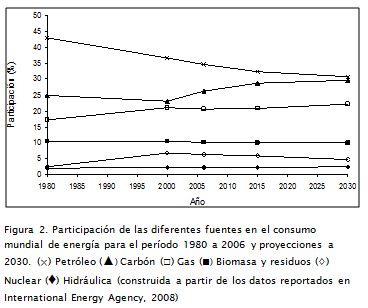

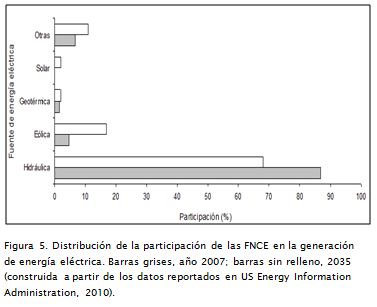

La Figura 2 muestra el aporte de cada una de las fuentes de energía a la demanda de energía primaria en el período comprendido entre 1980 y 2006, y las proyecciones a 2015, 2030 y 2035 (International Energy Agency, 2009). En ella se observa que la participación del petróleo disminuirá de 43% en 1980 a 30% en 2030, mientras que la hidráulica y la biomasa y los residuos participarán con el mismo porcentaje durante esos 50 años. El carbón, el gas y las fuentes de energía nuclear incrementarán su participación en 5% las dos primeras y en 2% la última.

De acuerdo a las proyecciones de la EIA, en 2035 los combustibles fósiles seguirán siendo la mayor fuente de energía, aunque el aporte por uso final de los combustibles líquidos crecerá muy poco o se reducirá, con excepción del sector del transporte, donde la ausencia de avances tecnológicos significativos tendrá como consecuencia que éstos seguirán siendo la principal fuente de energía (US Energy Information Administration, 2010). De la misma forma, la IEA afirma que los combustibles fósiles seguirán siendo la mayor fuente de energía primaria y que la demanda de petróleo aumentará en promedio 1% por año, pasando de 85 millones de barriles por día (bpd) en 2008 a 105 millones de bpd en 2030, incremento atribuible casi en su totalidad al sector transporte (International Energy Agency, 2009).

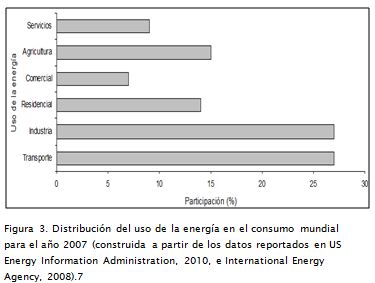

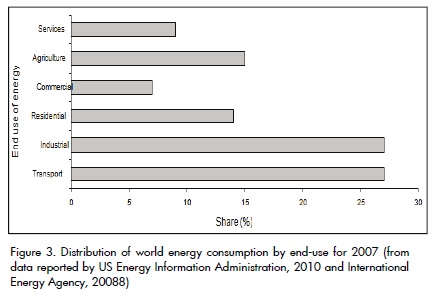

La Figura 3 muestra los porcentajes de energía de acuerdo con el uso. Aproximadamente el 55% de la energía producida se destina a los sectores transporte e industrial. En 2007 el mayor porcentaje de la energía en estos dos sectores provino de combustibles líquidos: el sector transporte consumió más del 50% de la energía proveniente de combustibles líquidos, que corresponde a 31% de la energía consumida en el sector (US Energy Information Agency, 2010). Estas cifras justifican que gran parte de los esfuerzos que buscan la diversificación de las fuentes de energía se centren en estos sectores y combustibles.

La EIA espera que el aporte de los combustibles líquidos a la energía que se utiliza en el sector industrial disminuya a 25% en 2035, principalmente por el incremento de los aportes del uso de energía eléctrica proveniente de diferentes fuentes, y de FNCE, que crecerán de 15% a 21% y de 7% a 8%, respectivamente, entre 2007 y 2035; en 2035 el 61% de la energía proveniente de los combustibles líquidos se usará en el sector transporte, aunque su aporte en los otros sectores disminuirá (US Energy Information Administration, 2010).

En Colombia el sector transporte demanda 39% de la energía final, y como en el resto del mundo, los combustibles fósiles son las principales fuentes de energía, a pesar de la oferta de gas natural vehicular (GNV) y de biocombustibles, esta última impulsada por políticas que obligan su consumo y fomentan su producción (UPME, 2007). Por otra parte, en 2005 el sector industrial consumió un tercio de la energía producida en Colombia y se ubica como el segundo consumidor después del transporte (UPME, 2007). El consumo de energía en los hogares es de 17% (UPME, 2007).

La mayor proporción de los combustibles líquidos que se consumen en el mundo corresponden al petróleo y a sus derivados. La producción mundial de petróleo en 2009 fue de 3.820 millones de t6, 2,6% menos que en 2008, reducción que se explica porque en 2009 el consumo mundial de energía se redujo 1,1%, la mayor disminución desde 1990 (British Petroleum Company, 2010). La IEA explica este comportamiento "como resultado de la crisis financiera y económica, pero con las políticas actuales, retomará rápidamente su tendencia al alza a largo plazo en cuanto se inicie la recuperación económica" (International Energy Agency, 2009). Sin embargo, la producción de petróleo en Colombia fue de 34,1 millones de t, 12,2% más que en 2008, y corresponde a menos del 1% de la producción mundial (British Petroleum Company, 2010).

La relación entre las reservas de petróleo y la producción, que da como resultado los años de disponibilidad, es de 45,7 años para 2009, mientras que en 2008 fue de 44,5 años; este aumento se explica por el incremento en las reservas de Indonesia y Arabia Saudita (British Petroleum Company, 2010). Desde 1986 esta relación se ha mantenido por encima de 40 años, siendo el valor para 2009 el mayor de ese período; lo anterior, porque a pesar de que el consumo de petróleo se incrementó en 10,5% entre 1999 y 2009, las reservas aumentaron en 22,8%. Las reservas de Colombia en 2009 fueron de 200 millones de toneladas, de forma tal que la relación reservas a producción es de 5,9 años, mientras que en 1999 la disponibilidad era de 7,5 años.

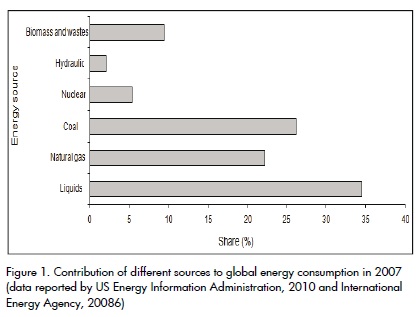

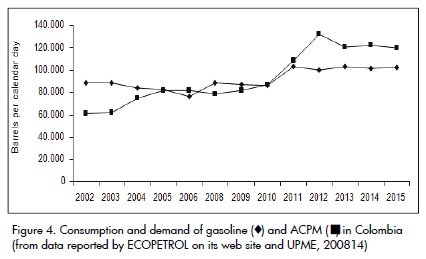

La Figura 4 presenta el consumo de gasolina y ACPM en Colombia hasta 2006 y la proyección de la demanda de éstos hasta 2015. Se observa que a partir de 2010 la demanda de ACPM superará la de gasolina, situación impulsada por las políticas que han mantenido su precio por debajo del de la gasolina.7

Fuentes no convencionales de energía

Las FNCE o fuentes de energía renovables son aquellas que no provienen de fósiles e incluyen el viento, el sol, la energía almacenada como energía interna en el aire (aerotérmica), debajo de la superficie de la tierra (geotérmica) y en el agua (hidrotérmica), la energía de los océanos, la hidráulica, la biomasa, los gases producidos en rellenos sanitarios y plantas de tratamiento de aguas residuales, y los biogases (The European Parliament, 2009).

Dentro de ellas, y desde la perspectiva global del impacto sobre el medio ambiente y la seguridad y el suministro energético, la biomasa9 se está convirtiendo en la fuente de energía líder en el corto plazo para el uso efectivo de las fuentes renovables de energía (Liang, 2008), aunque la energía eólica presentará el mayor crecimiento en el periodo 2007 a 2030 (International Energy Agency, 2009). Es fuente de la bioenergía que incluye la producción de combustibles como biogas, biohidrógeno, biocombustibles, biolíquidos, biocrudo y biogas de síntesis.

El URE también se considera como una fuente de energía. Definida tradicionalmente como la instalación de tecnologías que reducen las pérdidas de energía en casas, edificios e instalaciones industriales, hoy en día involucra mucho más, desde la reestructuración de políticas y el ofrecimiento de premios a los consumidores que usen menos energías, hasta el lanzamiento de programas educativos para enseñar a los estudiantes el vínculo entre el uso de la energía y el medio ambiente (Cooney, 2008).

Teniendo en cuenta que el 27% de la energía a nivel mundial se destina al sector transporte, y que un alto porcentaje de ella proviene de combustibles líquidos, especialmente gasolina y ACPM, y en menor proporción de combustibles gaseosos, como el gas natural, muchos países han implementado políticas para incentivar el uso de biocombustibles10 (The European Parliament, 2009; Senate and House of Representatives, 2009; Conpes, 2008). Los de mayor uso en el mundo son bioetanol y biodiesel, que en Colombia se usan desde el 2005 y el 2008, respectivamente, con base en la obligatoriedad que establecen las leyes 693 de 2001, para el etanol, y 934 de 2004, para el biodiesel.

La producción mundial de bioetanol en 2009 fue de 57,7 millones de t y la de biodiesel 15,2 millones de t, mientras que en Colombia se produjeron 241.800 t y 257.400 t, respectivamente (Biofuels Platform, 2010). De acuerdo con la Federación Nacional de Biocombustibles de Colombia, la capacidad instalada de producción de bioetanol es de 306.000 t año-1 en seis plantas, y la de biodiesel 516,00 t año-1 en siete plantas.11

Entre 2007 y 2009 hubo un cambio radical alrededor de las perspectivas del sector del biodiesel: de la discusión política y científica alrededor del impacto ambiental del biodiesel, a la sostenibilidad económica de la industria.12 title="">[12] Por ejemplo, el cambio en las políticas de soporte a los biocombustibles en Alemania redujo sustancialmente la demanda, que se redujo en 600.000 t de 2008 a 2009 (Lieberz, 2009), y se espera que en 2010 se use menos del 50% de la capacidad instalada para la producción de biodiesel en Europa (EU-27), y alrededor del 37% de la de bioetanol (Richey, 2008). Así, los esfuerzos se enfocan ahora hacia los biocombustibles de segunda y tercera generación, que se producen a partir de materias primas que no se utilizan para la alimentación, en su mayoría residuos agroindustriales o cultivos energéticos, de los que pueden obtenerse además moléculas más parecidas a las que se usan en la actualidad en automóviles, trenes y aviones, ampliando el mercado, que por ahora se ha concentrado en los automotores y vehículos de carga.

Con respecto al uso de biocombustibles, el bioetanol y el biodiesel representaron tan sólo el 1,5% de la demanda total de combustibles en 2006, y se espera que aporten alrededor de 6% en 2030, siendo mucho mayor la participación del bioetanol (International Energy Agency, 2008). En 2009 la producción de bioetanol fue el 1,5% de la producción mundial de petróleo y la de biodiesel de tan sólo 0,4%.

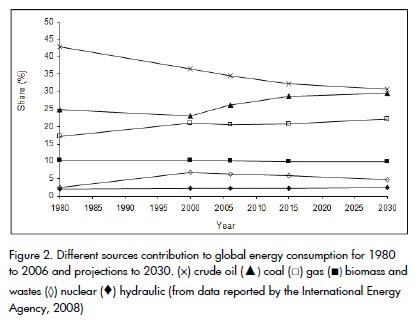

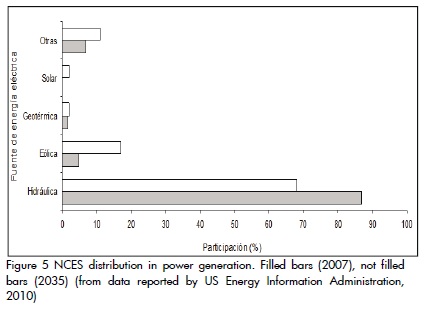

En 2007 la participación de las FNCE en la generación de energía eléctrica fue de 19%, y se espera que se incremente a 23% en 2035, mientras que en el sector industrial crecerá de 7,3% a 8,3% en el mismo período (US Energy Information Administration, 2010). La Figura 5 presenta la distribución de la participación de algunas de las FNCE en la generación de energía eléctrica de acuerdo con su origen. La energía hidráulica aporta más del 80% de la energía eléctrica de fuentes renovables, seguida por la eólica, con 4,8%. La EIA proyecta que en 2035 el comportamiento será similar, con incrementos significativos en la participación de las energías eólica y solar, que pasarían de 4,8% a 17% y de 0,2% a 2,1%, respectivamente.

En Colombia, durante agosto de 2010, el 63% de la energía eléctrica generada provino de centrales hidráulicas, mientras que el 32% de térmicas, la mayoría de ellas alimentadas con gas natural, que aportaron 446 GWh de los 4.821 GWh del Sistema Interconectado Nacional (SIN), mientras que las alimentadas con carbón generaron 235 GWh (UPME, 2010).

Plan de acción para promover el URE y las FNCE en Colombia

El Ministerio de Minas y Energía adoptó en junio de 2010 el Plan de Acción 2010-2015 para desarrollar el programa de uso racional y eficiente de la energía y demás FENC, que tiene como objetivo "contribuir a la competitividad de la economía colombiana, a través de la protección al consumidor y la promoción del uso de energías no convencionales de manera sostenible con el ambiente y los recursos naturales" (Ministerio de Minas y Energía, 2010).

Para ello propone "consolidar una cultura del manejo sostenible y eficiente de los recursos naturales a lo largo de la cadena energética, construir condiciones económicas, técnicas, regulatorias y de información que impulsen el URE y las FNCE; fortalecer las instituciones e impulsar iniciativas de carácter privado, mixto o de capital social para desarrollar programas y proyectos relacionados, y facilitar la aplicación de normas e incentivos tributarios" (Ministerio de Minas y Energía, 2010).

Los programas prioritarios se establecen de acuerdo con cuatro sectores: residencial, industrial, comercial, público y servicios, y transporte. En el sector industrial se propone la optimización del uso de la energía para fuerza motriz, calderas, procesos de combustión y la cadena de frío, así como el URE en PYME, entre otros objetivos. En el de transporte, la reconversión tecnológica, buenas prácticas y modos de transporte. Las metas de ahorro en energía eléctrica a 2015 en los sectores residencial, industrial y comercial, público y servicios, son de 10,6%, 5,3% y 4,4%, respectivamente. En el transporte se propone ahorrar 0,44% de energéticos por reconversión tecnológica de diesel a eléctricos en los buses articulados del sistema de transporte masivo y una fracción de los buses y busetas que harán parte del Sistema Integrado de Transporte Masivo (SITM) de Bogotá, y 0,16% por mejores prácticas de conducción y la entrada en operación del SITM de Bogotá (Ministerio de Minas y Energía 2010).

Como una muestra de las iniciativas para fomentar las FNCE a nivel mundial, a continuación se presentan algunas de las metas de las políticas de los Estados Unidos y de la Unión Europea. En el Energy Sucurity Act de 2007, el Congreso de los Estados Unidos aprobó una serie de acciones para la seguridad energética a través de mejorar la eficiencia de los combustibles en los vehículos, incrementar la producción de biocombustibles, ahorrar energía incrementando los estándares de iluminación, ahorrar energía en edificaciones y en la industria, y acelerando la investigación y el desarrollo en energía solar, geotérmica, marina e hidrocinética, entre muchas otras (Sissine, 2007).

Por ejemplo, se propone que la eficiencia en energía por empresa constructora de vehículos para 2020 debe ser mínimo de 35 millas por galón, y que las agencias federales, en 2015, deben ahorrar 20% del petróleo que consumieron en 2005 y obtener el 10% de fuentes alternativas (Sissine, 2007). La meta para 2025 consiste en que el 25% de la energía provenga de la agricultura, la silvicultura y las tierras de trabajo (Sissine, 2007).

Por otra parte, en la Unión Europea cada Estado miembro velará porque la cuota de energía procedente de fuentes renovables en todos los tipos de transporte en 2020 sea como mínimo equivalente al 10% de su consumo final de energía en el sector, y porque la cuota de energía procedente de fuentes renovables en su consumo final bruto de energía en 2020 sea coherente con un objetivo equivalente a una cuota de 20% como mínimo de energía procedente de fuentes renovables en el consumo final bruto de energía de la Comunidad para 2020 (The European Parliament, 2009).

Conclusión

Aunque la dependencia del petróleo como fuente predominante de energía se mantendrá por lo menos durante los próximos 25 años, son notables las políticas que propenden por la diversificación de las fuentes de energía. Los esfuerzos se centran en los sectores transporte e industrial, ya que juntos consumen más del 50% de la energía mundial, y en los combustibles líquidos.

Un aspecto común en las políticas europea, estadounidense y colombiana que promueven el uso eficiente de la energía y las fuentes no convencionales de energía, es la necesidad de realizar programas de investigación y desarrollo tecnológico que soporten las nuevas necesidades surgidas de las metas que se proponen. En éste, como en muchos aspectos de la ciencia y la tecnología, es necesario que cada país o región realicen sus propias investigaciones y desarrollos, ya que uno de los objetivos es aprovechar sus recursos para que los beneficios en generación de empleo y desarrollo rural que puedan surgir de estas iniciativas y mandatos se queden en sus territorios.

Un ejemplo es el caso de los biocombustibles: cada país investiga en sus recursos. Estados Unidos en maíz y soya, para producir bioetanol y biodiesel, y la Unión Europea en aceite de colza y girasol para la producción del último. No quiere decir que deba realizarse la investigación desde lo básico en todos lo casos, pero sí establecer los fundamentos de las particularidades de nuestros recursos para que la mayor parte de los beneficios se queden en nuestros países.

La universidad puede aportar tanto en la generación de conocimiento y la adaptación de tecnologías, como en la negociación de éstas con conocimiento del estado actual y de los verdaderos alcances e implicaciones de su implementación en el corto y en el largo plazo. También, por supuesto, en la formación de personal capacitado que pueda operar y mejorar las tecnologías que se pongan en marcha.

Bibliografía

Biofuels Platform. 2010. Production of biofuels in the World, data 2009, disponible en http://www.plateforme-biocarburants.ch/en /infos/production.php?id=bioethanol, consultada octubre 23 de 2010

British Petroleum Company., BP Statistical Review of World Energy, June 2010. disponible en http://www.bp.com/statisticalreview, consultado octubre 25 de 2010.

CONPES 3510. 2008,. Lineamientos de Política para Promover la Producción Sostenible de Biocombustibles en Colombia., marzo 31 de 2008.

Cooney, C., Energy Efficiency as an Energy Resource., Environmental Science & Technology, February 1, 2008, pp. 652-653.

International Energy Agency., World Energy Outlook 2009, Resumen Ejecutivo. disponible en http://www.worldenergyoutlook.org/docs/weo2009/WEO2009_es_spanish.pdf, consultado octubre 25 de 2010

International Energy Agency., World Energy Outlook 2008, Paris, 2008, pp 78-84.

Liang, D. T., Yan, R., Lee, D. H., Introduction to the Special Section of Energy & Fuels., Bioenergy Outlook 2007, Singapore, Energy & Fuels, Vol. 22, No. 1, January / February 2008.

Lieberz, S., Smaller German Biofuel Mandates Reduce Biodiesel Demand., GAIN Report GM 9032, United States Department of Agriculture, 8/7/2009.

Ministerio de Minas y Energía de Colombia., Resolución 180919., de junio de 2010.

Richey, B., Heute, S., EU 27 Bio-Fuels Annual 2008., GAIN Report E48063, United States Department of Agriculture, 5/30/2008.

Sissine, F., Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007: A Summary of Major Provisions., December 21, 2007.

The Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America., 2009. American Clean Energy and Security Act of H. R. 2454, 111th Session, 1st Congress, 2009.

The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. 2009., Directive 2009/28/EC, Official Journal of the European Parliament, 5.6.2009, L140/16.

US Energy Information Administration., International Energy Outlook 2010., Washington DC, 2010, pp. 1-9.

UPME., Plan Energético Nacional 2006-2025., abril de 2007.

UPME., Proyección Oferta de Demanda de Energía para el Sector Transporte Gasolina - Diesel - GNV., julio de 2008

UPME., Evolución de la Variables de Generación., septiembre de 2010.

2 Los países miembros de está organización (OECD, por sus siglas en inglés) son: Estados Unidos, Canadá, México, Austria, Bélgica, República Checa, Dinamarca, Finlandia, Francia, Alemania, Grecia, Hungría, Islandia, Irlanda, Italia, Luxemburgo, Holanda, Noruega, Polonia, Portugal, Eslovaquia, España, Suiza, Suecia, Turquía, Reino Unido, Japón, Corea del Sur, Australia, Nueva Zelanda y Chile, aunque los datos de este último no están incluidos en las cifras de la EIA (US Energy Information Administration, 2010).

3 12.000 millones de tep son aproximadamente 498 × 1015 BTU. Como las fuentes bibliográficas reportan la energía en diferentes unidades, para hacer la conversión se usó como poder calorífico promedio del petróleo 41,27 MJ kg-1.

4 Los datos reportados en esta fuente son para el año 2006. Los datos del año 2007 se calcularon a partir de los reportados en esa misma fuente para 1980, 2000, 2006, 2015 y 2030.

5 Los datos reportados en esta fuente son para el año 2006. Los datos para el año 2007 se calcularon a partir de los reportados en esa misma fuente para 1980, 2000, 2006, 2015 y 2030. Esta fuente discrimina los usos de la energía así: industrial, transporte, residencial-servicios-agricultura y usos no energéticos, mientras que la EIA los hace de la siguiente forma: residencial, comercial, industria y transporte.

6 Equivalen a 79.948 millones de barriles.

7 En promedio, el precio del ACPM es el 85% del de la gasolina.

8 Los datos hasta 2006 corresponden a consumo y fueron tomados de http://www.ecopetrol.com.co, consultada en julio 5 de 2010. Los datos a partir de 2008 corresponden a demanda y fueron tomados de UPME, 2008.

9 Biomasa es la fracción biodegradable de productos, desechos y residuos de origen biológico, proveniente de la agricultura (incluyendo sustancias de origen animal y vegetal), silvicultura, y de las industrias relacionadas con ella, como la pesquera y la acuicultura, así como la fracción biodegradable de los desechos industriales y municipales (The European Council, 2009).

10 Es un combustible líquido o gaseoso utilizado para el transporte, obtenido a partir de biomasa (The European Parliament, 2009).

11 Consultado en http://www.fedebiocombustibles.com/v2/nota-web-id-271.htm, octubre 23 de 2010.

12 Conclusión a partir de las presentaciones hechas por los líderes del sector que presentaron sus perspectivas en International Congress o Biodiesel: The Science and the Technology, organizado por la AOCS en Viena, Austria (2007) y Munich, Alemania (2009).

Paulo César Narváez Rincón1

1 Chemical Engineering. M.Sc., in Engineering. Ph.D., in engineering, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia. Research Group on Chemical and Biochemical Processes, Department of Chemical and Environmental Engineering, Universidad Nacional de Colombia. pcnarvaezr@bt.unal.edu.co

ABSTRACT

This article presents an overview of world and Colombian energy sources, including distribution, production and consumption by fuel and end-user sectors, respectively, as well as a brief description of some non-conventional energy sources (NCES), pointing out those classified as bioenergy and used as non-conventional fuels in the transport and electricity generating sectors. Colombian policies for promoting the rational use of energy (RUE) and NCES are presented and their targets are compared to some established by the European Union and the USA.

Keywords: energy, non-conventional energy source, biomass, biofuel.

Received: September 4th 2010

Accepted: november 15th 2010

Introduction

The recent publication of resolution 180919 by the Ministry of Mines and Energy presenting the action plan for developing a programmme for the rational use of energy (RUE) and other non-conventional energy sources (NCES) in Colombia forms part of a series of initiatives by governments from countries on five continents seeking to help them solve some of the most important problems facing society in the 21st century. This includes their dependence on oil as the main source of energy and raw material for many chemicals, the finite nature of this natural resource, the negative impact on the environment of power generation and rural unemployment and underdevelopment.

NCES are intended to increase energy security and independence, reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and improving the economy´s competitiveness, especially in developing countries where they are most needed, due to high unemployment and poverty rates, factors forcing people to move to big cities (internal migration) or to other countries, mainly the USA, Europe and Australia, to seek a better standard of living.

Biomass, sun, wind, waves, water and heat stored in the air and beneath the surface of the earth are energy sources having different levels of technological maturity which are or may be used for gradually replacing oil as the main source of energy. Although all of them are being used, the use of water for generating electricity and biomass for producing biofuels are the most widespread, given their availability, technological maturity and, in the case of liquid biofuels, the possibility of using them without changing the combustion engines of the vehicles we use today.

This article presents an overview of world and Colombian energy sources, including distribution of use by fuel type and end-user sectors. Succinctly, it describes some NCES and specifies those that are classified as bioenergy. Subsequently, Colombian policies for promoting RUE and NCES are presented and their targets are compared to some by the European Economic Community and the USA. It is proposed that academia can play a role in developing and implementting these energy sources.

Energy overview

According to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), world energy consumption in 2007 was 495.2 × 1015 BTU and 1.4% expected annual growth up to 2035, being higher in countries which are not members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (US Energy Information Administration, 2010). Liquid fuel, including oil and its derivatives, ethanol, biodiesel, coal liquefaction products and gas are the main sources of energy and contributed about 85 quadrillion BTU in 2007, 35% of the total, although it is expected that their share will decrease by 30% in 2035 (US Energy Information Administration, 2010). Moreover, the International Energy Agency (IEA) has reported that world energy demand will increase from 12,000 million tons of oil equivalent (Mtoe) in 2007 to 16,800 Mtoe in 2030, an increase of 40% (International Energy Agency, 2009). Central and South-American countries consumed only 5.6% of world energy consumption in 2007; share will increase to 5.9% and 6.2% in 2015 and 2035, respectively (US Energy Information Administration, 2010). According to the British Petroleum Company (British Petroleum Company, 2010), global primary energy consumption in 2009 was 11,164 Mtoe, 29.0 of that in Colombia (less than 0.26% of total).

Figure 1 shows the distribution of different energy sources in global consumption for 2007. Fossil fuels were the major source of energy; liquid fuels accounted for 35% and coal for 27%. In 2009, 34.8% of primary energy came from oil, 23.8% from natural gas and 29.4% from coal (British Petroleum Company, 2010). The situation was similar in Colombia and oil accounted for 30.3% of total energy. However, a remarkable difference to global behaviour was that hydropower accounted for 32.1% and coal only 10.7% (despite the availability of this natural resource in Colombia) (British Petroleum Company,2010)

Primary energy consumption in Colombia was 1,134.7 × 1012 BTU in 2005, 24% more than in 1990 and supply was distributed as follows according to source (UPME, 2007): oil 48%, natural gas 21%, hydro 12% and wood and coal 5.5%. Consumption for the same year had the following distribution: gasoline, diesel and other petroleum products 48%, electricity 19%, natural gas 15%, coal 8%, wood and bagasse 7%, and other sources 3% (UPME, 2007).

Figure 2 shows the contribution of each energy source to primary energy demand between 1980 and 2006 and projections to 2015, 2030 and 2035 (International Energy Agency, 2009). Oil contribution will decline from 43% in 1980 to 30% in 2030, while hydro, biomass and waste will maintain the same share percentage during these 50 years. Coal, gas and nuclear energy sources will increase their share by 5% for the first two and 2% for the last one.

Fossil fuels will remain the major energy source by 2035 according to EIA projections, although end-use by type of fuel contribution regarding liquid fuels will be constant or will decrease, with the exception of the transport sector, where the absence of significant technological advances will mean that these will remain the primary energy source (US Energy Information Administration, 2010). Likewise, the IEA says that fossil fuels will remain the largest source of primary energy and oil demand will increase by an average of 1% per year, from 85 million barrels per day (bpd) in 2008 to 105 million bpd in 2030, an increase almost entirely attributable to the transportation sector (International Energy Agency, 2009).

Figure 3 shows energy percentages according to end-use. Around 55% of the energy produced is intended for the transport and Industrial sectors. The highest percentage of energy in these two areas in 2007 came from liquid fuels: the transport sector consumed 50% more energy from liquid fuels, corresponding to 31% of the energy consumed in the sector (US Energy Information Agency, 2010). This data justified many efforts seeking to diversify energy sources focusing on these sectors and fuels.

The EIA expects that liquid fuels´ contribution to the energy used in the industrial sector decreased to 25% in 2035, mainly due to the increased contribution of alternative sources to generating electricity and NCES, which will grow from 15% to 21% and 7% to 8%, respectively, between 2007 and 2035. In this year, 61% of energy from liquid fuels will be used in the transport sector, although its contribution in other sectors will decrease (US Energy Information Administration, 2010).

The transport sector in Colombia consumes 39% of all energy and, as in the rest of the world, fossil fuels are the main source, in despite of use of natural gas (CNG) and biofuels, the latter driven by policies encouraging consumption and forcing production (UPME, 2007). Moreover, in 2005, the industrial sector consumed a third of the energy produced in Colombia and ranked as second largest consumer after transport (UPME, 2007). Energy consumption in the residential sector was 17% (UPME, 2007).

The largest percentage of liquid fuels consumed in the world corresponds to oil and its derivatives. World oil production was 3,820 million t6 in 2009, 2.6% less than in 2008, such reduction being due to world energy consumption dropping 1.1% in 2009, the biggest decline since 1990 (British Petroleum Company, 2010). The IEA says that this behaviour was "a result of financial and economic crisis, but with current policies, will quickly start again their upward trend as long-term economic recovery begins" (International Energy Agency, 2009). Oil production in Colombia was 34.1 million t, 12.2% higher than in 2008, and corresponded to less than 1% of world production (British Petroleum Company, 2010).

The ratio between oil reserves and production, resulting in years of availability, was 45.7 years for 2009, while in 2008 it was 44.5 years, such rise being explained by increased reserves in Indonesia and Saudi Arabia (British Petroleum Company, 2010). This ratio has remained above 40 years since 1986, the value for 2009 being the highest in this period because, although oil consumption increased by 10.5% between 1999 and 2009, reserves increased 22.8%. Colombia's reserves were 200 million tones in 2009 so that reserves to production ratio was 5.9 years, while availability was 7.5 years in 1999.

Figure 4 shows the consumption of gasoline and diesel fuel in Colombia until 2006 and the projected demand for them until 2015. It should be noted that from 2010 demand will exceed that of diesel fuel, a situation driven by policies that have kept the price below that of gasoline7

Non-conventional sources of energy

NCES or renewable energy sources are those from non-fossil sources involving wind and sun energy stored as internal energy in the air (aerothermal), below the surface of the earth (geothermal) and water (hydrothermal), ocean energy, hydropower, biomass, landfill gas produced in plants and wastewater treatment and biogas (The European Parliament, 2009).

Biomass is becoming the leading short-term energy source for the effective use of renewable energy sources within the above and from the global perspective of impact on the environment and security and energy supply (Liang, 2008), although wind energy will present the greatest growth from 2007 to 2030 (International Energy Agency, 2009). Bomass is a source of bioenergy which allows the production of fuels such as biogas, bio-hydrogen, biofuels, bioliquids, biocrude and synthetic biogas.

Te rational use of energy (RUE) is also considered a source of energy. Traditionally defined as the installation of technologies that reduce energy loss in homes, buildings and industrial facilities, today this involves much more following the restructuring of policies and offering rewards to consumers who use less energy, until the release of educational programmes to teach students the link between energy use and environment (Cooney, 2008).

Given that 27% of global energy is used by transport and a high percentage of it comes from liquid fuels, especially gasoline and diesel fuel, and a lower proportion of gas fuels such as natural gas, many countries have implemented policies to encourage the use of biofuels (The European Parliament, 2009, Senate and House of Representatives, 2009; CONPES, 2008). The most popular ones in the world are bioethanol and biodiesel which have been used in Colombia since 2005 and 2008, respectively, based on the requirement established by law 693/2001 for ethanol and 934/2004 for biodiesel.

World bioethanol production in 2009 was 57.7 million t, while 241,800 t were produced in Colombia. For biodiesel, 15.2 million t were produced in the world and 257,400 t in Colombia (Biofuels Platform, 2010). According to the Colombian Federation of Biofuels, installed capacity for bioethanol production is 306,000 t yr-1 in six process plants while it is 516,00 t yr-1 for biodiesel in seven process plants.11.

There was a radical change in perspectives about the biodiesel Industry between 2007 and 2009 from the political and scientific debate about the environmental impact of biodiesel to the industry´s economic sustainability. For example, change in support policies for biofuels in Germany, substantially reduced demand which fell by 600,000 t from 2008 to 2009 (Lieberz, 2009). It is expected that in 2010 less than 50% of installed capacity for the production of biodiesel in Europe will be used (EU-27) and about 37% for bioethanol(Richey, 2008). Thus, efforts are now focused towards second- and third-generation biofuels which are produced from raw materials that are not used for food, mostly agro-industrial waste or energy

crops that can be used to obtain molecules similar to those currently used in cars, trains and planes, expanding the market, which so far has focused on automobiles and trucks.

Biofuels, bioethanol and biodiesel accounted for only 1.5% of total fuel demand in 2006 and is expected to contribute around 6% in 2030, most provided by bioethanol (International Energy Agency, 2008). Ethanol production was 1.5% of world production of oil and biodiesel in 2009, as little as 0.4%.

NCES share in power generation was 19% in 2007 and is expected to increase to 23% in 2035, while contribution in the industrial sector will grow from 7.3% to 8.3% over the same period (US Energy Information Administration, 2010). Figure 5 shows the distribution of the share of some of the NCES in electricity generation according to origin. Hydropower provides more than 80% of electricity from renewable sources, wind 4.8%. The EIA projects that behaviour will be similar in 2035, accompanied by significant increases in the share of wind and solar energy increasing from 4.8% to 17.0% and 0.2% to 2.1%, respectively.

63% of the electricity generated during August 2010 in Colombia came from hydropower, while 32% came from thermal power, most fuelled by natural gas which contributed 446 GWh of the 4,821 GWh from the Colombian Interconnected System (CIS), while coal generated 235 GWh (UPME, 2010).

Action plan for promoting RUE and NCES in Colombia

The Colombian Ministry of Mines and Energy adopted an action plan in June 2010 (2010-2015) for developing an RUE and other NCES programme whose objective is to contribute towards the Colombian economy´s competitiveness through consumer protection and promoting the sustainable use of non-conventional energy, protecting the environment and natural resources (Ministry of Mines and Energy, 2010).

Moreover, the action plan is aimed at consolidating a culture of efficient and sustainable management of natural resources throughout the energy chain, developing economic, technical, regulatory and communication conditions promoting RUE and NCES, strengthen institutions and promote private, mixed or social capital initiatives for developing programmes and projects and facilitate the implementation of standards and tax incentives (Ministry of Mines and Energy, 2010).

Priority programmes were established according to five sectors: residential, industrial, commercial, public and services and transportation. It is proposed optimising the use of energy for motive power, boilers, combustion processes and the cold chain and URE in small and medium-sized companies in the industrial sector. Conversion technology, best practices and modes of transport are the targets in the transport sector. Electricity saving goals by 2015 in the residential, industrial and commercial public services are 10.6%, 5.3% and 4.4%, respectively. The proposals in the transport sector include 0.44% energy saving by converting articulated buses and a fraction of the other buses and minibuses in the massive transport system (MTS) from diesel powered engines to electric ones, and 0.16% for better driving practices and MTS entering into operation in Bogota (Ministry of Mines and Energy 2010).

Some US and European Union policy goals are presented as an example of efforts to promote global NCES. In the Security Energy Act of 2007, the United States Congress approved a series of actions for energy security by improving fuel efficiency in vehicles, increasing biofuel production, improving energy saving lighting standards, saving energy in buildings and industry and accelerating R&D in solar, geothermal, marine and hydrokinetic energy (Sissine, 2007).

For instance, it is proposed that corporate average fuel economy should be at least 35 miles per gallon while in 2015 federal agencies should save 20% of the oil consumed in 2005 and get 10% alternative sources (Sissine, 2007). The goal for 2025 is that 25% of energy comes from agriculture, forestry and working lands (Sissine, 2007).

Moreover, "in the light of the positions taken by the European Parliament, the Council and the Commission, it is appropriate to establish mandatory national targets consistent with a 20% share of energy from renewable sources and a 10% share of energy from renewable sources in transport in Community energy consumption by 2020" (The European Parliament, 2009).

Conclusion

Although dependence on oil as an energy source will remain dominant for at least the next 25 years, there are remarkable policies which promote the diversification of energy sources. Efforts will focus on the transport and industrial sectors because these sectors together consume more than 50% of global energy and liquid fuels. A common feature in European, American and Colombian policies promoting the efficient use of energy and non-conventional sources

of energy is the need for research programmes and technological development supporting new needs arising from the goals proposed. In this field, as in many aspects of science and technology, it is necessary that each country or region do their own R&D because one of the objectives is to leverage its resources thereby generating employment and rural development may arise from these initiatives.

An example is the case of biofuels; each country researching their own resources. For instance, corn and soybeans for producing bioethanol and biodiesel are investigated in the USA while in the European Union rapeseed and sunflower oil for the production of the latter are being studied. This does not mean basic research in all cases, but laying the foundations for specific aspects of national resources so that most of the benefits remain in the countries producing them.

The university can both generate knowledge and adapt technologies and can help to negotiate these with state of the art knowledge and the true scope and implications of its implementation in the shortand long-term. The university can also educate qualified the necessary personnel for operating and improving technologies that are alreadyin place.References

Biofuels Platform. 2010. Production of biofuels in the World, data 2009, disponible en http://www.plateforme-biocarburants.ch/en /infos/production.php?id=bioethanol, consultada octubre 23 de 2010

British Petroleum Company., BP Statistical Review of World Energy, June 2010. disponible en http://www.bp.com/statisticalreview, consultado octubre 25 de 2010.

CONPES 3510. 2008,. Lineamientos de Política para Promover la Producción Sostenible de Biocombustibles en Colombia., marzo 31 de 2008.

Cooney, C., Energy Efficiency as an Energy Resource., Environmental Science & Technology, February 1, 2008, pp. 652-653.

International Energy Agency., World Energy Outlook 2009, Resumen Ejecutivo. disponible en http://www.worldenergyoutlook.org/docs/weo2009/WEO2009_es_spanish.pdf, consultado octubre 25 de 2010

International Energy Agency., World Energy Outlook 2008, Paris, 2008, pp 78-84.

Liang, D. T., Yan, R., Lee, D. H., Introduction to the Special Section of Energy & Fuels., Bioenergy Outlook 2007, Singapore, Energy & Fuels, Vol. 22, No. 1, January / February 2008.

Lieberz, S., Smaller German Biofuel Mandates Reduce Biodiesel Demand., GAIN Report GM 9032, United States Department of Agriculture, 8/7/2009.

Ministerio de Minas y Energía de Colombia., Resolución 180919., de junio de 2010.

Richey, B., Heute, S., EU 27 Bio-Fuels Annual 2008., GAIN Report E48063, United States Department of Agriculture, 5/30/2008.

Sissine, F., Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007: A Summary of Major Provisions., December 21, 2007.

The Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America., 2009. American Clean Energy and Security Act of H. R. 2454, 111th Session, 1st Congress, 2009.

The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. 2009., Directive 2009/28/EC, Official Journal of the European Parliament, 5.6.2009, L140/16.

US Energy Information Administration., International Energy Outlook 2010., Washington DC, 2010, pp. 1-9.

UPME., Plan Energético Nacional 2006-2025., abril de 2007.

UPME., Proyección Oferta de Demanda de Energía para el Sector Transporte Gasolina - Diesel - GNV., julio de 2008

UPME., Evolución de la Variables de Generación., septiembre de 2010.

Footnotes

4 Data reported in this reference is for 2006. 2007 data was calculated from datapresented in the same reference for 1980, 2000, 2006, 2015 and 2030.

5 Data reported in this source is for 2006. Data for 2007 was calculated from the same source reported in 1980, 2000, 2006, 2015 and 2030. This source discriminates energy use: industrial, transportation, residential-service-agriculture and non-energy use, while the EIA lists it as follows: residential, commercial, industrial and transportation

6Equivalent to 79.948 million barrels.

7 On average, the price of diesel is 85% that of gasoline.

8 Data is for consumption until 2006 and was taken from http://www.ecopetrol.com.co, accessed July 5 2010. Data from 2008 was taken from demand and UPME, 2008.

11 Accessed http://www.fedebiocombustibles.com/v2/nota-web-id-271.htm, October 23rd 2010.

References

Biofuels Platform. 2010. Production of biofuels in the World, data 2009, disponible en http://www.plateforme-biocarburants.ch/en/infos/production.php?id=bioethanol, consultada octubre 23 de 2010

British Petroleum Company., BP Statistical Review of World Energy, June 2010. disponible en http://www.bp.com/statisticalreview, consultado octubre 25 de 2010.

CONPES 3510. 2008,. Lineamientos de Política para Promover la Producción Sostenible de Biocombustibles en Colombia., marzo 31 de 2008.

Cooney, C., Energy Efficiency as an Energy Resource., Environmental Science & Technology, February 1, 2008, pp. 652-653. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/es087096y

International Energy Agency., World Energy Outlook 2009, Resumen Ejecutivo. disponible en http://www.worldenergyoutlook.org/docs/weo2009/WEO2009_es_spanish.pdf, consultado octubre 25 de 2010

International Energy Agency., World Energy Outlook 2008, Paris, 2008, pp 78-84.

Liang, D. T., Yan, R., Lee, D. H., Introduction to the Special Section of Energy & Fuels., Bioenergy Outlook 2007, Singapore, Energy & Fuels, Vol. 22, No. 1, January / February 2008. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/ef700561x

Lieberz, S., Smaller German Biofuel Mandates Reduce Biodiesel Demand., GAIN Report GM 9032, United States Department of Agriculture, 8/7/2009.

Ministerio de Minas y Energía de Colombia., Resolución 180919., de junio de 2010.

Richey, B., Heute, S., EU 27 Bio-Fuels Annual 2008., GAIN Report E48063, United States Department of Agriculture, 5/30/2008.

Sissine, F., Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007: A Summary of Major Provisions., December 21, 2007.

The Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America., 2009. American Clean Energy and Security Act of H. R. 2454, 111th Session, 1st Congress, 2009.

The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. 2009., Directive 2009/28/EC, Official Journal of the European Parliament, 5.6.2009, L140/16.

US Energy Information Administration., International Energy Outlook 2010., Washington DC, 2010, pp. 1-9.

UPME., Plan Energético Nacional 2006-2025., abril de 2007.

UPME., Proyección Oferta de Demanda de Energía para el Sector Transporte Gasolina - Diesel - GNV., julio de 2008

UPME., Evolución de la Variables de Generación., septiembre de 2010.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

License

Copyright (c) 2010 Paulo César Narváez Rincón

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The authors or holders of the copyright for each article hereby confer exclusive, limited and free authorization on the Universidad Nacional de Colombia's journal Ingeniería e Investigación concerning the aforementioned article which, once it has been evaluated and approved, will be submitted for publication, in line with the following items:

1. The version which has been corrected according to the evaluators' suggestions will be remitted and it will be made clear whether the aforementioned article is an unedited document regarding which the rights to be authorized are held and total responsibility will be assumed by the authors for the content of the work being submitted to Ingeniería e Investigación, the Universidad Nacional de Colombia and third-parties;

2. The authorization conferred on the journal will come into force from the date on which it is included in the respective volume and issue of Ingeniería e Investigación in the Open Journal Systems and on the journal's main page (https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/ingeinv), as well as in different databases and indices in which the publication is indexed;

3. The authors authorize the Universidad Nacional de Colombia's journal Ingeniería e Investigación to publish the document in whatever required format (printed, digital, electronic or whatsoever known or yet to be discovered form) and authorize Ingeniería e Investigación to include the work in any indices and/or search engines deemed necessary for promoting its diffusion;

4. The authors accept that such authorization is given free of charge and they, therefore, waive any right to receive remuneration from the publication, distribution, public communication and any use whatsoever referred to in the terms of this authorization.